Suburban Residents’ Preferences for Livable Residential Area in Finland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

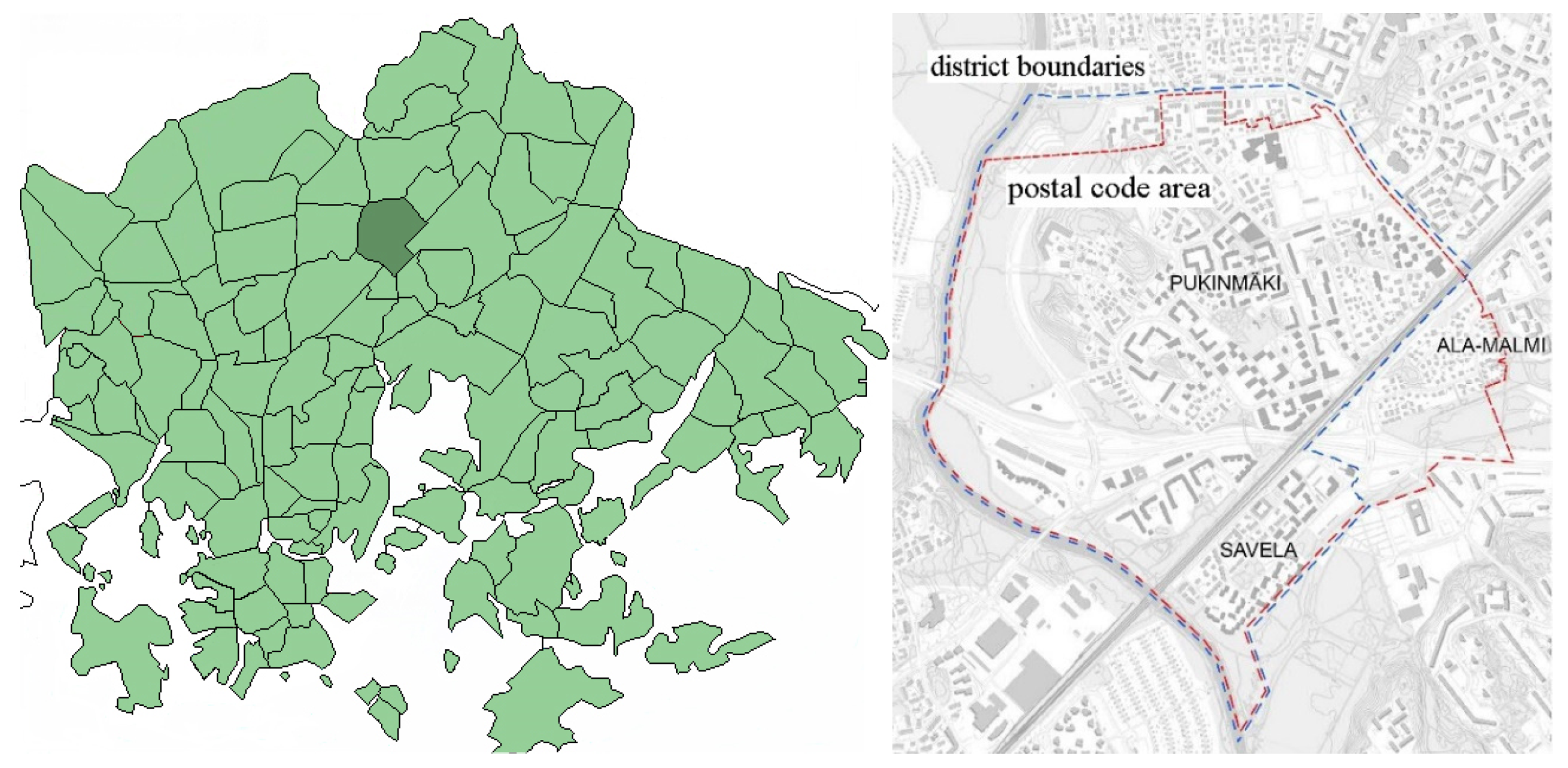

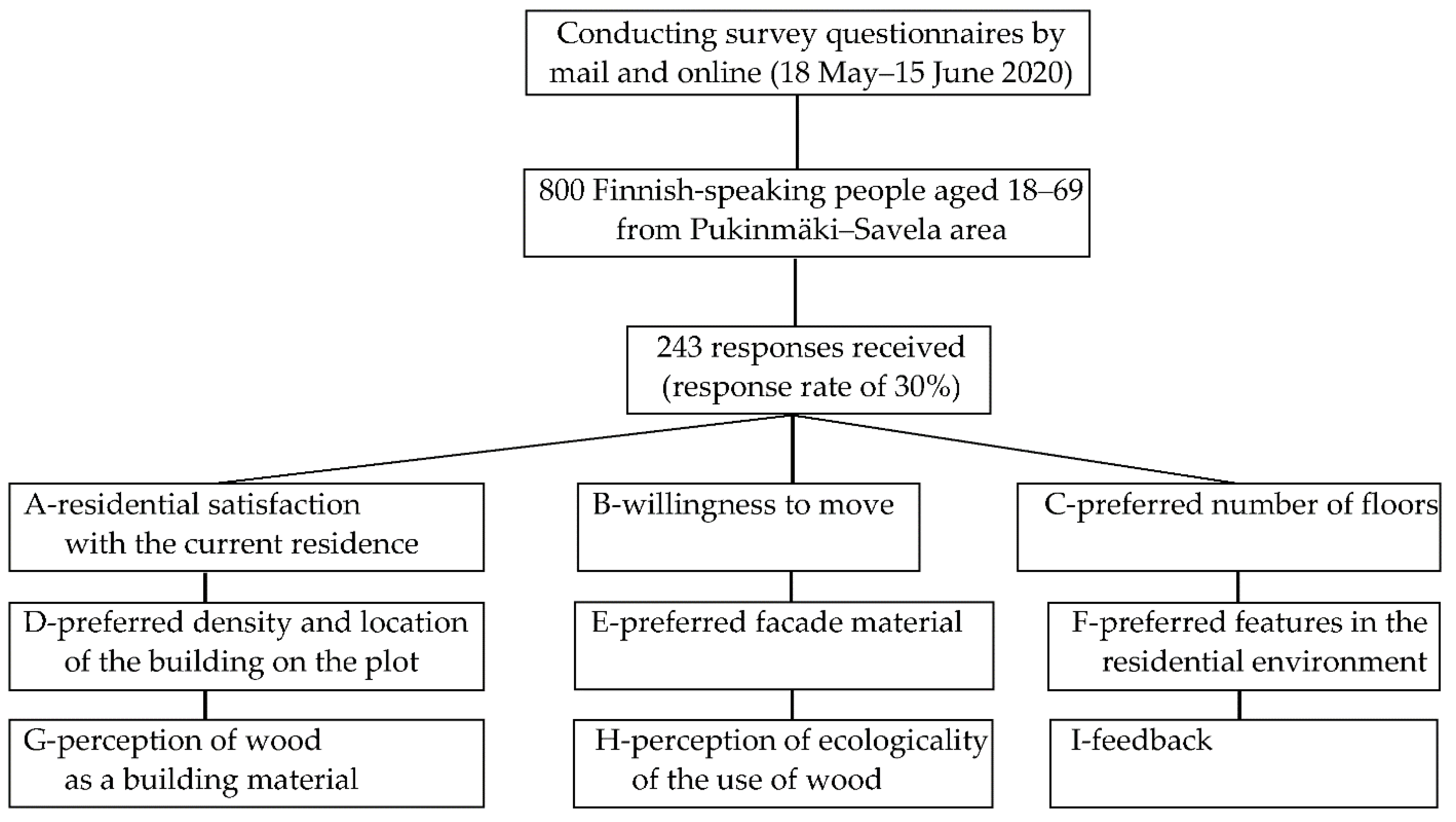

2. Research Method

3. Results

3.1. Background Information

3.2. Residential Satisfaction with the Current Residence

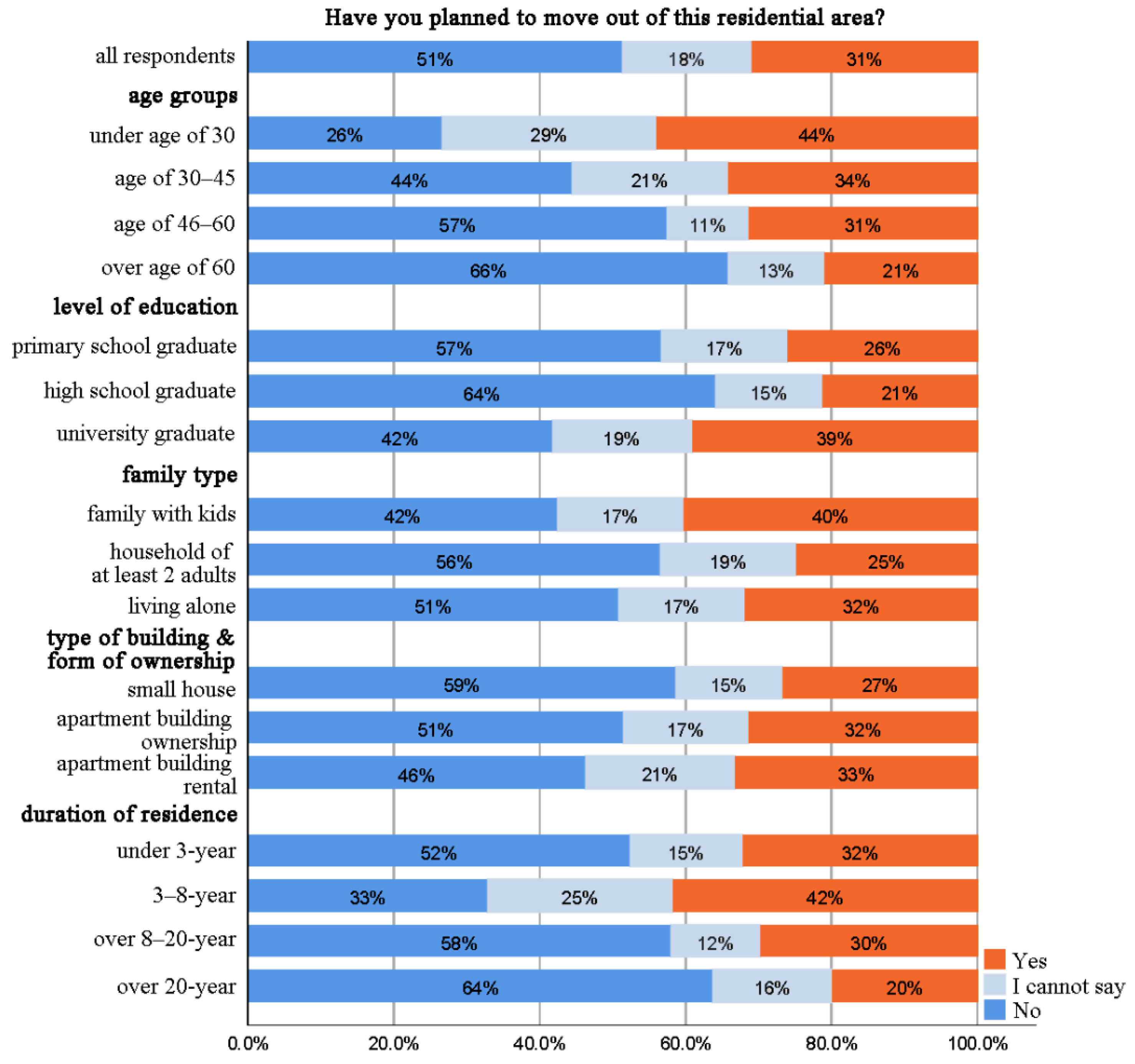

3.3. Willingness to Move

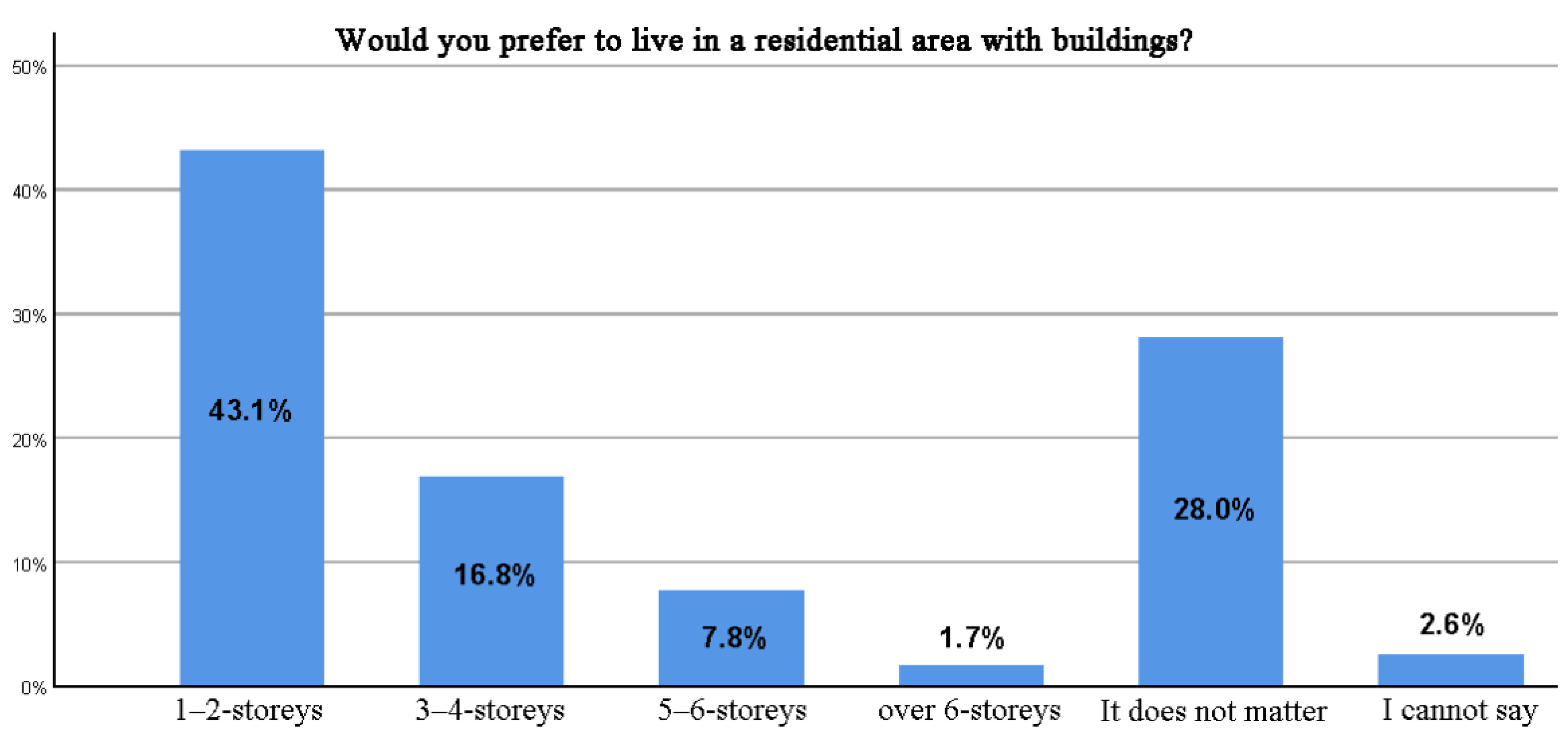

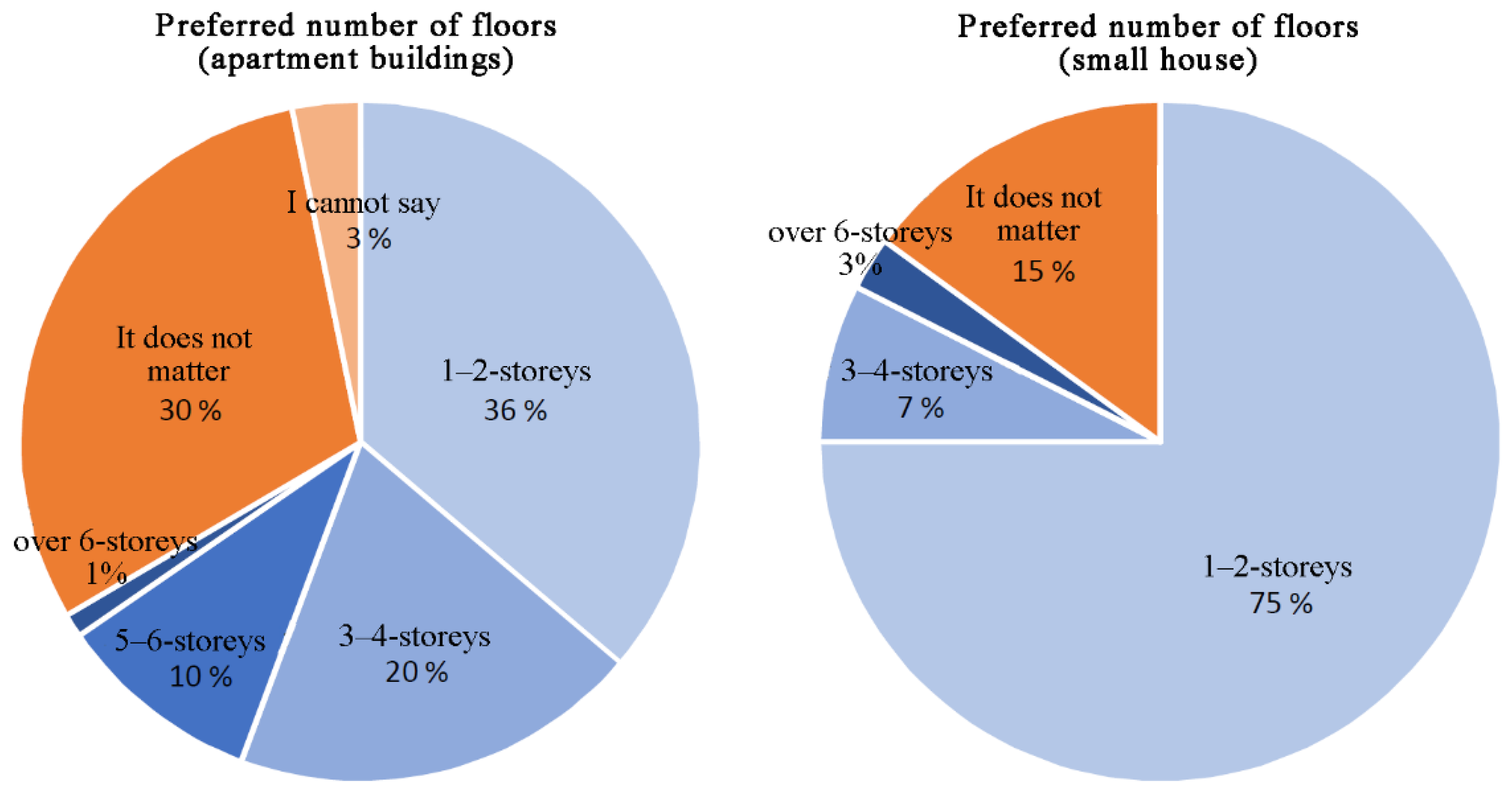

3.4. Preferred Number of Floors

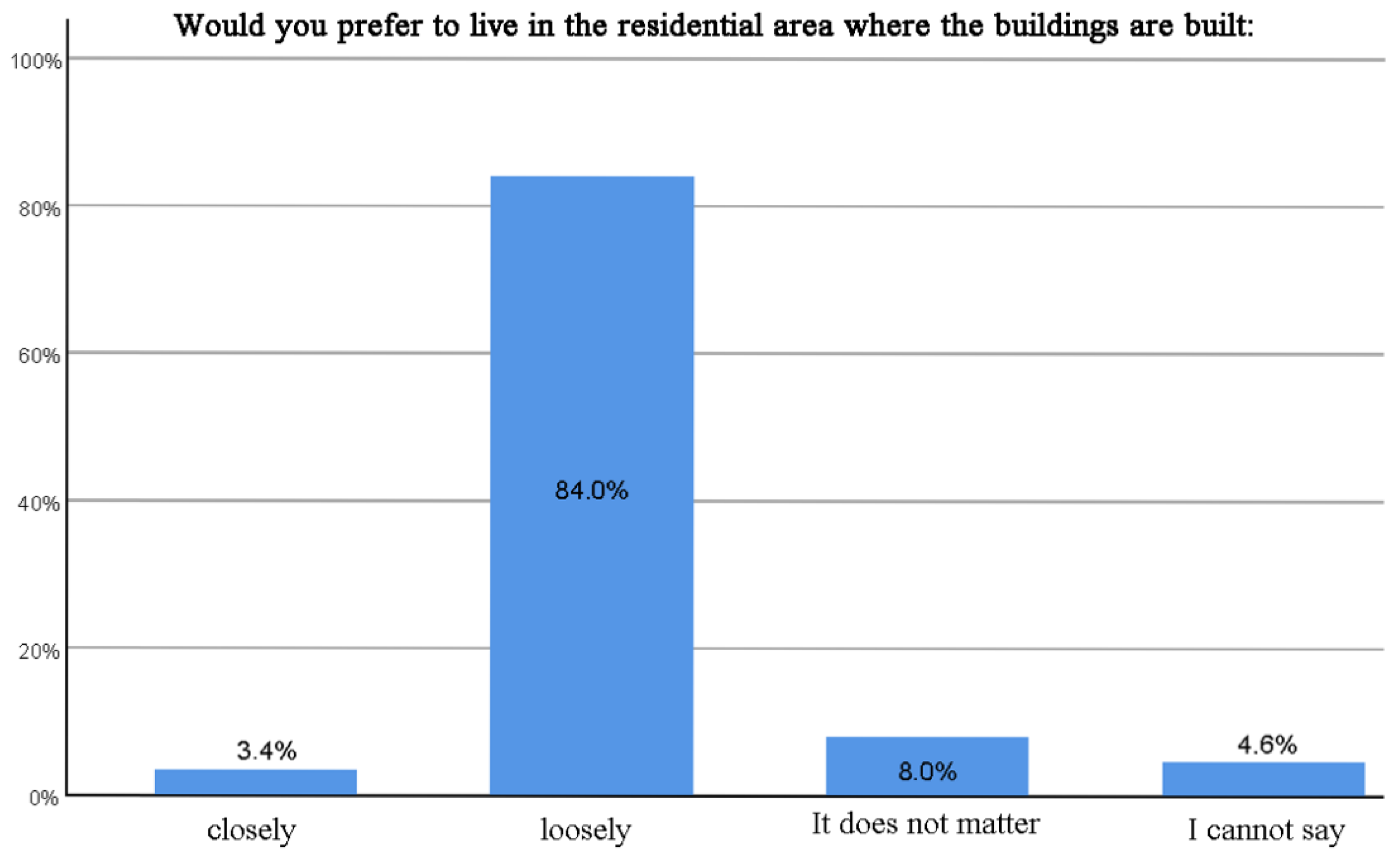

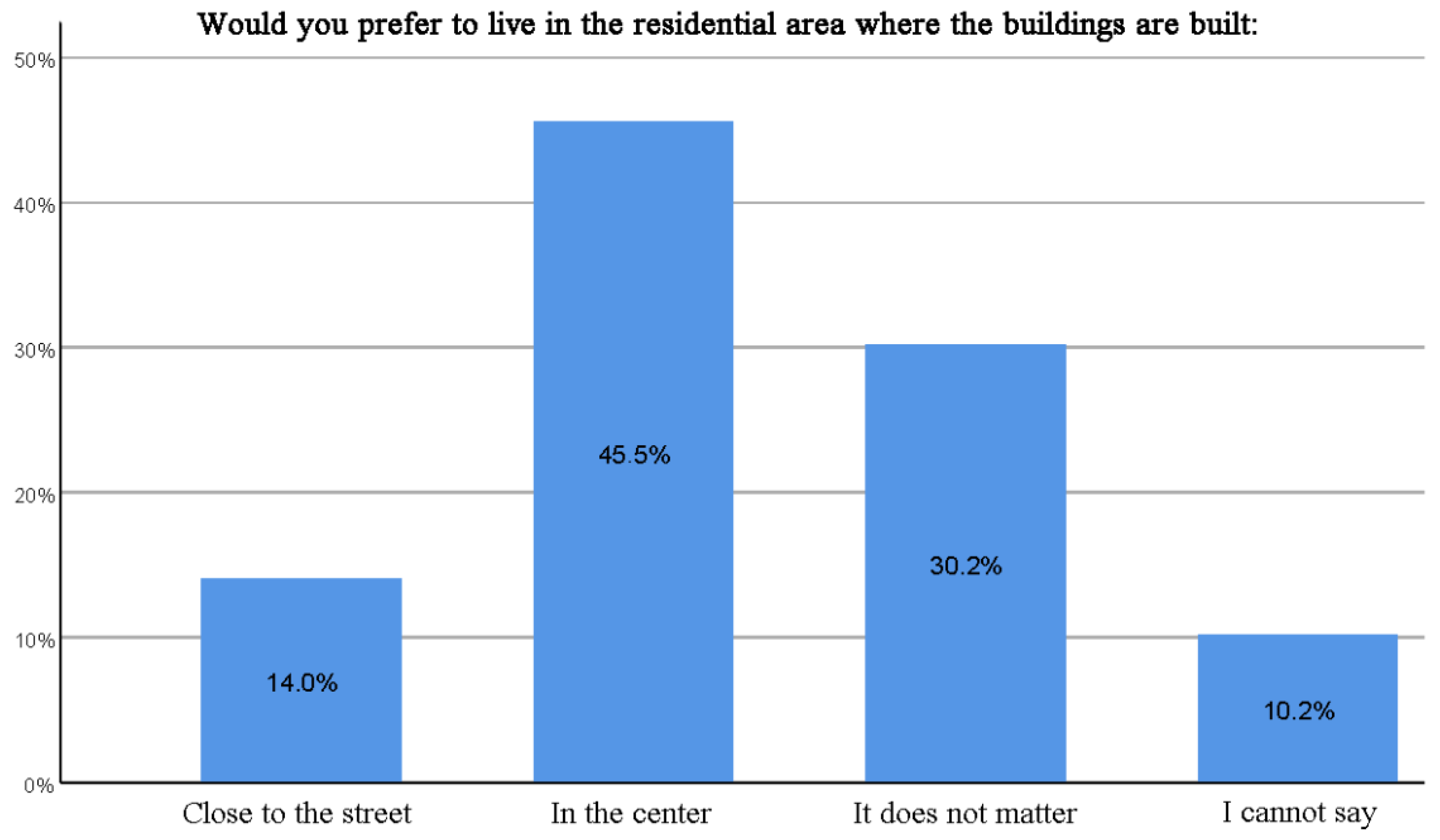

3.5. Preferred Density and Location of the Building on the Plot

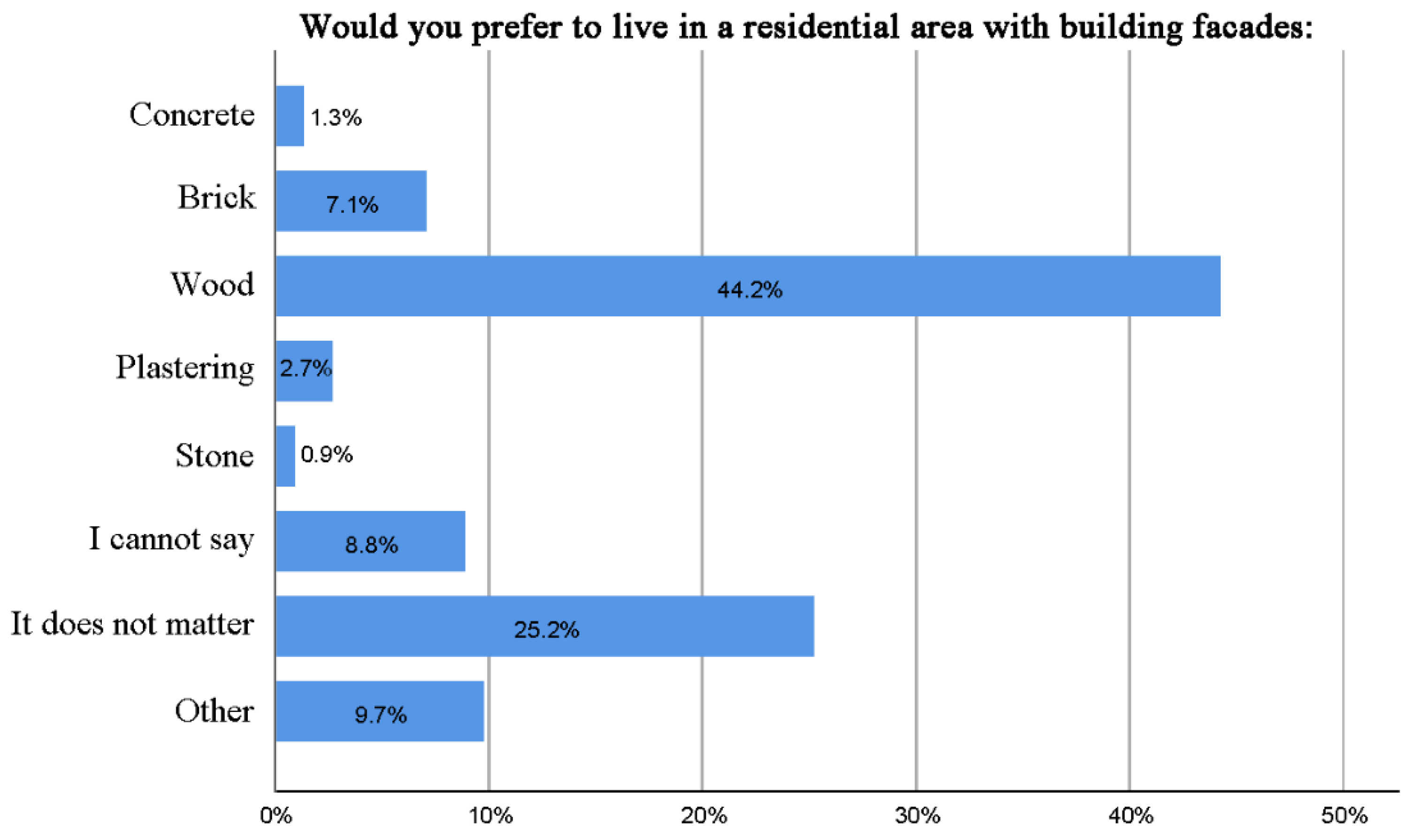

3.6. Preferred Facade Material

3.7. Preferred Features in the Residential Environment

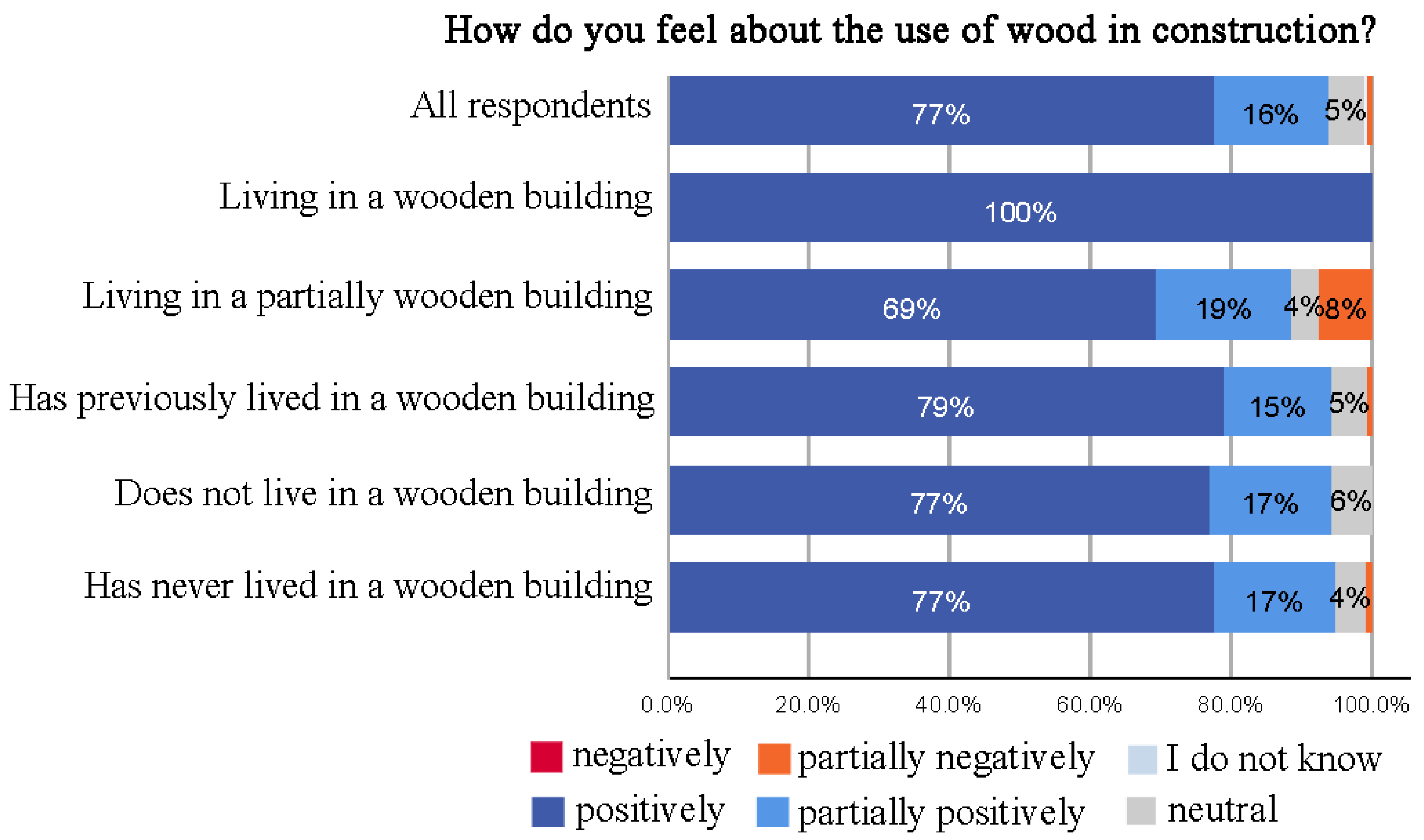

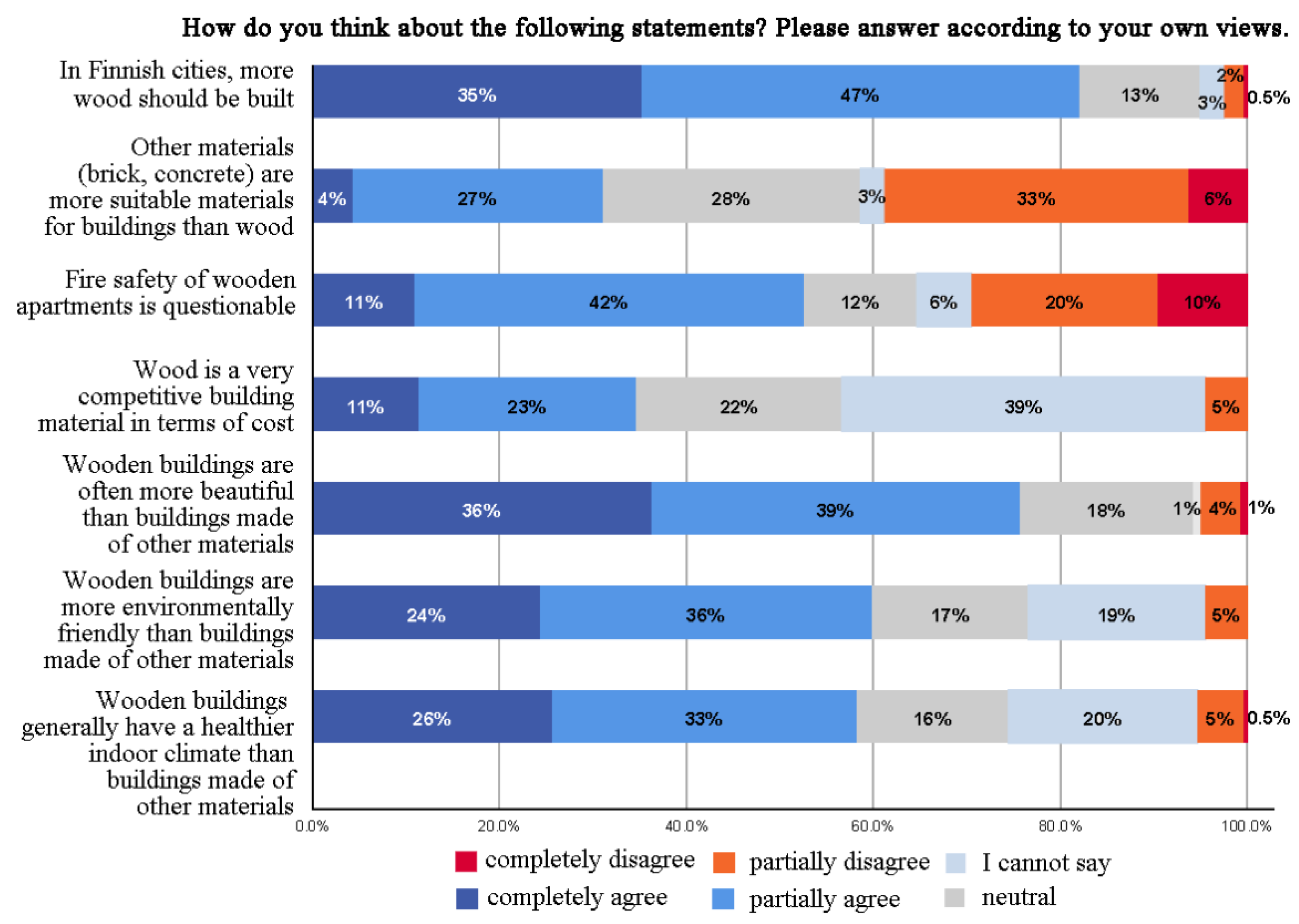

3.8. Perception of Wood as a Building Material

3.9. Perception of the Ecologicality of the Use of Wood

3.10. Feedback

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- 1.

- Date of response: _______________

- 2.

- Respondent’s gender: * Female * Male

- 3.

- Respondent’s age: _______Level of education: * Primary school * High school * University * I cannot say

- 4.

- Size of respondent’s household: ___________ adults, __________ children (<18 y)

- 5.

- Form of ownership: * Rental * Owned * Right-of-occupancy * Elsewhere? __________

- 6.

- How long have you lived in your current residence: _______years ________months.

- 7.

- What kind of building do you live in? * Apartment * Semi-detached house* Detached house * Elsewhere? __________In the survey, wooden structure refers to a structure whose external appearance is mostly wooden, that is, its facade is wooden.

- 8.

- Is your residential building a wooden building? * Yes * No * I cannot say

- 9.

- Have you lived in a wooden building before? * Yes * No * I cannot say

- 10.

- How do you feel about?Very satisfied/Satisfied/Neutral/Dissatisfied/Very dissatisfied/I cannot say

- (a)

- your area of residence

- (b)

- quality of your residence

- (c)

- price/rent level of your residence

- 11.

- What was the most important influence on the choice of your current place of residence? __________

- 12.

- Are you planning to move from this residential area?

- (a)

- * Yes * No * I cannot say

- (b)

- If you answered that you are planning to move: Why would you want to move? And where?

- 13.

- What do you think about the use of wood in construction?* Positive * Partially positive * Neutral * Partially negative * Negative * I cannot say

- 14.

- Do you think about the use of wood in construction?* Ecological * Somewhat ecological * Neither ecological nor non-ecological* Somewhat non-ecological * Non-ecological * I cannot say

- 15.

- If you wish, give reasons for your answers to questions 14 and 15. __________

- 16.

- What do you think about the following?Completely agree/Partially agree/Neutral/Partially disagree/Disagree/I cannot say

- (a)

- In Finnish cities

more wood should be built- (b)

- Other materials

(brick, concrete)are more suitable materialsfor buildings than wood- (c)

- The fire safety of wooden

apartment is questionable- (d)

- Wood is a very competitive

building material in terms of cost- (e)

- Wooden buildings are often

more beautiful than buildingsmade of other materials- (f)

- Wooden buildings are generally

more environmentally friendlythan buildings made of other materials- (g)

- Wooden buildings generally have

a healthier indoor climate thanbuildings made of other materials

- 17.

- Would you rather live in a residential area with buildings:* 1–2-storey * 3–4-storey * 5–6-storey * more than 6-storey* It does not matter * I cannot say

- 18.

- Would you prefer to live in a residential area with building facades:* Concrete * Stone * Brick * Steel * Wood* Ceramic tile * Plastering * I cannot say* Facade materials do not matter * Elsewhere? __________

- 19.

- Would you prefer to live in a residential area where the buildings are located on a plot of land:* Close to the street * In the center * It does not matter * I cannot say

- 20.

- Would you prefer to live in the residential area where the buildings are built:* Closely * Loosely * It does not matter * I cannot say

- 21.

- Which of the following factors is more important on the facade of the building for a pleasant living environment?

- * Facade material or facade coloring

- * Facade material or facade architecture

- * Facade coloring or facade architecture

References

- Tuominen, P. Historical and Spatial Layers of Cultural Intimacy: Urban Transformation of a Stigmatised Suburban Estate on the Periphery of Helsinki. Soc. Incl. 2020, 8, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simson, R.; Fadejev, J.; Kurnitski, J.; Kesti, J.; Lautso, P. Assessment of Retrofit Measures for Industrial Halls: Energy Efficiency and Renovation Budget Estimation. Energy Procedia 2016, 96, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, V.; Kuusi, H. From city streets to suburban woodlands: The urban planning debate on children’s needs, and childhood reminiscences, of 1940s–1970s Helsinki. Urban Hist. 2019, 48, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hankonen, J. Lähiöt ja Tehokkuuden Yhteiskunta: Suunnittelujärjestelmän Läpimurto Suomalaisten Asuntoalueiden Rakentumisessa 1960-Luvulla; Gaudeamus: Otatieto, Finland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- The New Arrival of the Suburbs, YIT. Available online: https://www.yit.fi/en/in-focus/future-of-suburbs (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- The Finnish Timber of Council (Puuinfo). Available online: https://puuinfo.fi/?lang=enç (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- The Bright Future of Suburbs, YIT. Available online: https://news.cision.com/yit-oyj/r/the-bright-future-of-suburbs,c3023589 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Musterd, S.; van Kempen, R. Large-scale Housing Estates in European Cities: Opinions of Residents on Recent Developments. RESTATE Report 4k; Urban and Regional Research Centre: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, R.; Musterd, S.; van Kempen, R. (Eds.) Mass Housing in Europe: Multiple Faces of Development, Change and Response; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wassenberg, F. Large Housing Estates: Ideas, Rise, Fall and Recovery. The Bijlmermeer and Beyond. Sustainable Urban Areas; Delft University Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saarikangas, K. Merkityksellinen Tila: Lähiöasuminen Arkkitehtuurin, Asukkaiden, Aenneen ja Nykyisen Nohtaamisena. In Eletty ja Muistettu Tila. Historiallinen Arkisto, 115; Syrjämaa, T., Tunturi, J., Eds.; Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura: Helsinki, Finland, 2002; pp. 48–75. [Google Scholar]

- Saarikangas, K. Asukkaat ja Maisema Liikkeessä: Lähiörakentaminen ja asumisen mullistus 1960-luvulla. In Värikkäämpi, Iloisempi, Hienostuneempi: Näkökulmia 1960-Luvun Arkkitehtuuriin; Lahti, J., Rauske, E., Eds.; Arkkitehtuurimuseo: Helsinki, Finland, 2016; pp. 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Costly City Homes, Crumbling Country Houses—Finland’s Top 5 Housing Problems. Available online: https://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/news/costly_city_homes_crumbling_country_houses__finlands_top_5_housing_problems/10447688 (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Huttunen, H.; Blomqvist, E.; Ellilä, E.; Hasu, E.; Perämäki, E.; Tervo, A.; Verma, I.; Ullrich, T.; Utriainen, J. The Finnish Townhouse as a Home. Starting Points and Interpretations. Habitat Components—Townhouse. Final Report. Aalto University Publication Series CROSSOVER 8/2017. Helsinki, Finland, 2017. Available online: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/30185/isbn9789526071220.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- There is a Need for Diverse, Market-Driven Housing Construction and for State-Subsidised, Affordable Housing Production to Supplement it, Housing Policy, Finnish Government. Available online: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/marin/government-programme/housing-policy (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Wood Construction Is Being Promoted in Finland, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Finland. Available online: https://mmm.fi/en/en/forests/use-of-wood/wood-construction (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Suburban Regeneration, The City of Helsinki. Available online: https://www.uuttahelsinkia.fi/en/sustainable-urban-development/suburban-regeneration/suburb-programme (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Toppinen, A.; Autio, M.; Sauru, M.; Berghäll, S. Sustainability-driven new business models in wood construction towards 2030. In Towards a Sustainable Bioeconomy: Principles, Challenges and Perspectives; Leal-Filho, W., Pociovalisteanu, D.M., Borges-de-Brito, P.R., Borges-de-Lima, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 499–516. [Google Scholar]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Consuming Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary configuration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McMeekin, A.; Southerton, D. Sustainability transitions and final consumption: Practices and socio-technical systems. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2012, 24, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram-Hanssen, K. Retrofitting owner-occupied housing: Remember the people. Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; McMeekin, A.; Mylan, J.; Southerton, D. A critical appraisal of Sustainable Consumption and Production research: The reformist, revolutionary and reconfiguration positions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 34, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjernberg, M. Concrete Suburbia: Suburban Housing Estates and Socio-Spatial Differentiation in Finland. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geosciences and Geography A 77, Faculty of Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karjalainen, M. The Finnish Multi-Story Timber Apartment Building as a Pioneer in the Development of Timber Construction; University of Oulu: Oulu, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Karjalainen, M. Timber Apartment Building Resident and Developer Survey 2017; Final Report; Finland’s Ministry of the Environment: Helsinki, Finland, 2017.

- Kovacs-Györi, A. Cabrera-Barona, P. Assessing Urban Livability through Residential Preference—An International Survey. Data 2019, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Kamp, I.; Leidelmeijer, K.; Marsman, G.; de Hollander, A. Urban environmental quality and human well-being: Towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts; a literature study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blečić, I.; Bibo Cecchini, A.; Talu, V. The Capability Approach in Urban Quality of Life and Urban Policies: Towards a Conceptual Framework. In City Project and Public Space; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; ISBN 9789400760370. [Google Scholar]

- Pacione, M. URBAN LIVEABILITY: A REVIEW. Urban Geogr. 1990, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs-Györi, A.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Resch, B.; Mehaffy, M.; Blaschke, T. Assessing and Representing Livability through the Analysis of Residential Preference. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Young, E.; Hermanson, V. Livability Literature Review: A Synthesis of Current Practice; TRID: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Booi, H.; Boterman, W.R. Changing patterns in residential preferences for urban or suburban living of city dwellers. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2019, 35, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karjalainen, M.; Ilgın, H. The Change over Time in Finnish Residents’ Attitudes towards Multi-Story Timber Apartment Buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.A.; Nilsson, K.; Tunström, M.; Dis, A.T.; Perjo, L.; Berlina, A.; Costa, S.O.; Fredricsson, C.; Grunfelder, J.; Johnsen, I.; et al. White Paper on Nordic Sustainable Cities Developed by Nordregio, Nordregio Magazine. 2017. Available online: http://www.nordregio.se/nordicsustainablecities (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), the United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material/ (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Smart City, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd. Available online: https://www.vttresearch.com/en/topics/smart-city (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Litman, T. Where We Want to be Home Location Preferences and Their Implications for Smart Growth, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, The Congress for New Urbanism Transportation Summit 4 November 2009, Portland, Oregon. Available online: https://www.vtpi.org/sgcp.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Jansen, S.J. Urban, suburban or rural? Understanding preferences for the residential environment. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2020, 13, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhan, D.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Yu, J.; Dang, Y. Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities 2018, 79, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkar, A.S.; Macwan, J.E.M. Criteria Analysis of Residential Location Preferences: An Urban Dwellers’ Perspective. Int. J. Urban Civ. Eng. 2018, 12, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.; Haarhoff, E.; Beattie, L. Enhancing liveability through urban intensification: The idea and role of neighbourhood. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 1442117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, K. Residents’ preferences for walkable neighbourhoods. J. Urban Des. 2016, 22, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tapsuwan, S.; Mathot, C.; Walker, I.; Barnett, G. Preferences for sustainable, liveable and resilient neighbourhoods and homes: A case of Canberra, Australia. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinniah, G.K.; Shah, M.Z.; Vigar, G.; Aditjandra, P.T. Residential Location Preferences: New Perspective. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 17, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrić, J.; Bajic, T. Variability of Suburban Preference in a Post-socialist Belgrade. In Proceedings of the 3rd Human and Social Sciences at the Common Conference, online, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 134–139. Available online: www.hassacc.com (accessed on 24 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Report on the Survey on the Provision of Livable Housing Design: The Costs and Benefits to Australian Society, RCD.9999.0439.0001, Australian Network for Housing Design. 2018. Available online: https://agedcare.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-08/RCD.9999.0439.0001.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Lukuman, M. Sustainable Livable Housing Assessment Model for Traditional Urban Areas in Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Built Environment and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Östman, B.; Brandon, D.; Frantzich, H. Fire safety engineering in timber buildings. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 91, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viholainen, N.; Kylkilahti, E.; Autio, M.; Toppinen, A. A home made of wood: Consumer experiences of wooden building materials. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, F. Living quality in wooden multi-family houses. PRO LIGNO 2019, 15, 434–441. [Google Scholar]

- City of Helsinki. Available online: https://www.hel.fi/helsinki/en/ (accessed on 24 October 2021).

- Ali, M.M.; Al-Kodmany, K. Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat of the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Buildings 2012, 2, 384–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lähtinen, K.; Harju, C.; Toppinen, A. Consumers’ perceptions on the properties of wood affecting their willingness to live in and prejudices against houses made of timber. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 14, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; Röhr, A.; Pätäri, S.; Lähtinen, K.; Toivonen, R. The future of wooden multistory construction in the forest bio-economy—A Delphi study from Finland and Sweden. J. For. Econ. 2018, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Häyrinen, L.; Toppinen, A.; Toivonen, R. Finnish young adults’ perceptions of the health, well-being and sustainability of wooden interior materials. Scand. J. For. Res. 2020, 35, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylkilahti, E.; Berghäll, S.; Autio, M.; Nurminen, J.; Toivonen, R.; Lähtinen, K.; Vihemäki, H.; Franzini, F.; Toppinen, A. A consumer-driven bioeconomy in housing? Combining consumption style with students’ perceptions of the use of wood in multi-story buildings. Ambio 2020, 49, 1943–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høibø, O.; Hansen, E.; Nybakk, E.; Nygaard, M. Preferences for urban building materials: Does building culture background matter? Forests 2018, 9, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gold, S.; Rubik, F. Consumer attitudes towards timber as a construction material and towards timber frame houses—Selected findings of a representative survey among the German population. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larasatie, P.; Guerrero, J.E.; Conroy, K.; Hall, T.E.; Hansen, E.; Needham, M.D. What Does the Public Believe about Tall Wood Buildings? An Exploratory Study in the US Pacific Northwest. J. For. 2018, 116, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallo, M.F.L.; Espinoza, O. Awareness, perceptions and willingness to adopt Cross-Laminated Timber by the architecture community in the United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; O’Neill, T.; Zuo, J.; Skitmore, M.; Chen, Q.; Skitmore, R. Perceived obstacles to multi-storey timber-frame construction: An Australian study. Arch. Sci. Rev. 2014, 57, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bayne, K.; Taylor, S. Attitudes to the Use of Wood as a Structural Material in Non-Residential Building Applications: Opportunities for Growth; Australian Government, Forest and Wood Products Research and Development Corporation: Melbourne, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs-Györi, A. GIS-based Livability Assessment: A Practical Tool, a Promising Solution? In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Geographical Information Systems Theory, Applications and Management (GISTAM 2019), Heraklion, Crete, Greece, 3–5 May 2019; pp. 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karjalainen, M.; Ilgın, H.E.; Metsäranta, L.; Norvasuo, M. Suburban Residents’ Preferences for Livable Residential Area in Finland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11841. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111841

Karjalainen M, Ilgın HE, Metsäranta L, Norvasuo M. Suburban Residents’ Preferences for Livable Residential Area in Finland. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11841. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111841

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarjalainen, Markku, Hüseyin Emre Ilgın, Lauri Metsäranta, and Markku Norvasuo. 2021. "Suburban Residents’ Preferences for Livable Residential Area in Finland" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11841. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111841

APA StyleKarjalainen, M., Ilgın, H. E., Metsäranta, L., & Norvasuo, M. (2021). Suburban Residents’ Preferences for Livable Residential Area in Finland. Sustainability, 13(21), 11841. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111841