The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions in Brand Equity, Brand Credibility, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intentions

Abstract

:1. Research Background and Motivation

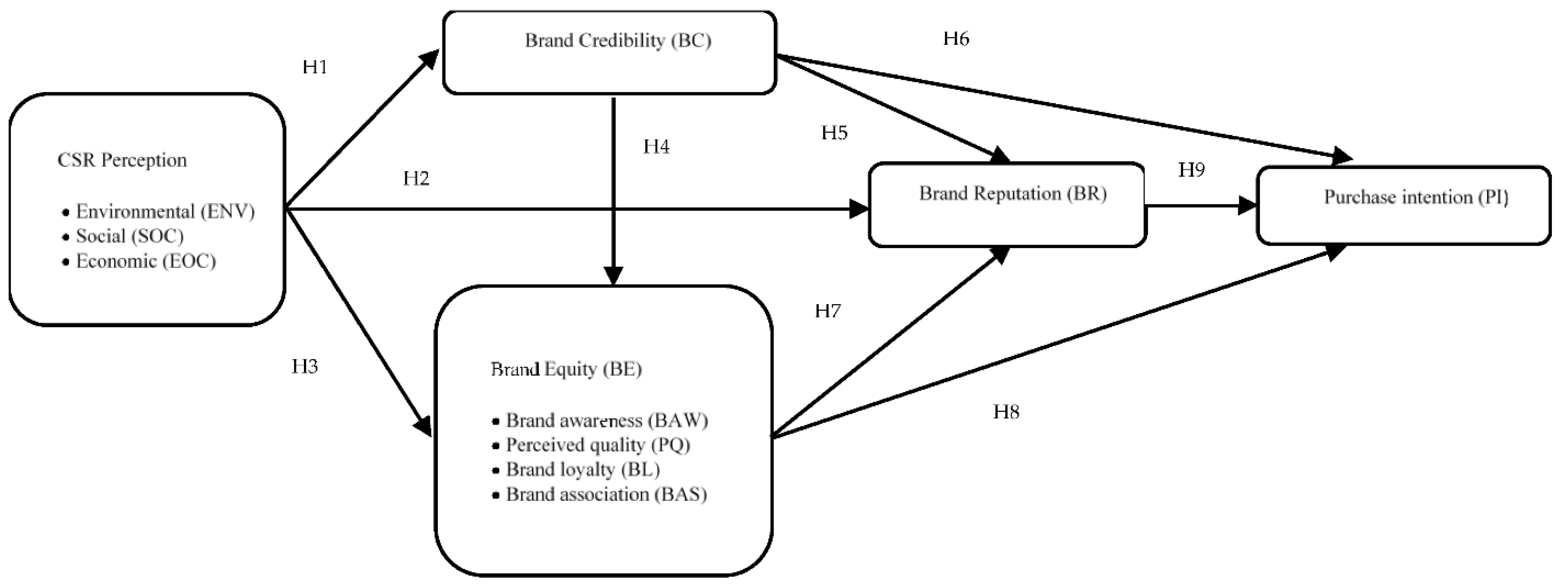

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. CSR Perceptions and Brand Credibility, Brand Reputation, and Brand Equity

2.2. Brand Credibility, Brand Equity, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intention

2.3. Brand Equity, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intention

2.4. Brand Reputation and Purchase Intentions

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Research Design

3.3. Research Instrument and Measurement

3.4. Questionnaire Translation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Respondent Characteristics

4.2. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

4.2.1. Assessment of R2 Value

4.2.2. Assessment of Effect Size f2

4.3. Evaluation of the Structural Model

4.3.1. Multicollinearity Test

4.3.2. Direct and Indirect Effects

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

5.1. Research Conclusion

5.2. Academic Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Research Constructs and Items | Mean | SD | Adopted from |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Dimension (SOC) | Fatma et al. [103]; Park et al. [104]; Park [30] | ||

| [SOC1] | 5.66 | 1.186 | |

| [SOC2] | 5.61 | 1.123 | |

| [SOC3] | 5.61 | 1.210 | |

| [SOC4] | 5.68 | 1.202 | |

| [SOC5] | 5.76 | 1.169 | |

| Economic Dimension (ECO) | |||

| [ECO1] | 5.96 | 1.051 | |

| [ECO2] | 5.98 | 1.057 | |

| [ECO3] | 5.92 | 1.042 | |

| [ECO4] | 5.94 | 1.077 | |

| Environmental Dimension (ENV) | |||

| [ENV1] | 5.66 | 1.234 | |

| [ENV2] | 5.61 | 1.261 | |

| [ENV3] | 5.64 | 1.213 | |

| [ENV4] | 5.60 | 1.234 | |

| [ENV5] | 5.50 | 1.319 | |

| Brand Awareness (BAW) | Schivinski and Dabrowski [105]; Chen [106] | ||

| [BAW1]” | 5.68 | 1.117 | |

| [BAW2] | 5.66 | 1.120 | |

| [BAW3] | 5.68 | 1.133 | |

| [BAW4] | 5.66 | 1.098 | |

| Brand Association (BAS) | Aaker [73] | ||

| [BAS1] | 6.03 | 0.923 | |

| [BAS2] | 6.07 | 0.912 | |

| [BAS3] | 6.01 | 0.926 | |

| [BAS4] | 6.01 | 0.983 | |

| [BAS5] | 6.01 | 0.923 | |

| Perceived Quality (PQ) | Vukasović [107]; Schivinski and Dabrowski [105] | ||

| [PQ1] | 5.74 | 1.119 | |

| [PQ2] | 5.68 | 1.089 | |

| [PQ3] | 5.72 | 1.166 | |

| [PQ4] | 5.68 | 1.138 | |

| [PQ5] | 5.67 | 1.174 | |

| [PQ6] | 5.72 | 1.116 | |

| Brand Loyalty (BL) | Moreira et al. [108]; Sahina et al. [109] | ||

| [BL1] | 6.02 | 0.944 | |

| [BL2] | 6.04 | 0.908 | |

| [BL3] | 6.00 | 0.961 | |

| [BL4] | 6.02 | 0.931 | |

| [BL5] | 6.00 | 0.976 | |

| [BL6] | 6.01 | 0.981 | |

| [BL7] | 5.63 | 1.192 | |

| [BL8] | 5.54 | 1.359 | |

| Brand Credibility (BC) | Erdem and Swait [44]; Hur et al. [11]; Dwivedi et al. [110] | ||

| [BC1] | 5.92 | 0.913 | |

| [BC2] | 5.93 | 0.980 | |

| [BC3] | 5.94 | 0.972 | |

| [BC4] | 5.95 | 0.949 | |

| Brand Reputation (BR) | Veloutsou and Moutinho [111] | ||

| [BR1] | 5.69 | 0.901 | |

| [BR2] | 5.69 | 0.895 | |

| [BR3] | 5.68 | 0.915 | |

| [BR4] | 5.71 | 0.913 | |

| Purchase Intention (PI) | Kudeshia and Kumar [112]; Schivinski and Dabrowski [105]; Yoo et al. [113]; Shukla [114] | ||

| [PI1] | 5.69 | 0.873 | |

| [PI2] | 5.69 | 0.957 | |

| [PI3] | 5.73 | 0.940 | |

References

- Foroudi, P. Influence of brand signature, brand awareness, brand attitude, brand reputation on hotel industry’s brand performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 76, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H. The effect of CSR Fit and CSR authenticity on the brand attitude. Sustainability 2019, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agudelo, M.A.L.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of cor-porate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, R.; Langer, M.; Konrad, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, stakeholders and sustainable development I: A theoretical exploration of business–Society relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, N.F.; Lane, N. Corporate social responsibility: Impacts on strategic marketing and customer value. Mark. Rev. 2009, 9, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayyad, H.M.A.; Obeidat, Z.M.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Abuhashesh, M.; Maqableh, M.; Masa’deh, R. Corporate social responsibility and patronage intentions: The mediating effect of brand credibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 27, 510–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Monitor. Strategic Insights: CSR & Sustainability in the Beauty Industry. 2010. Available online: http://www.organicmonitor.com/709160.htm. (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- McDougall, A. CSR and Sustainability Key to Improving Company Image in Cosmetics. 2010. Available online: http://www.cosmeticsdesign-europe.com/MarketTrends/CSR-and-sustainability-key-to-improving-company-image-in-cosmetics. (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Baalbaki, S.; Guzmán, F. A consumer perceived consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.S.; Chiu, C.J.; Yang, C.F.; Pai, D.C. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Moon, T.W.; Jun, J.K. The role of perceived organizational support on emotional labor in the airline industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Verma, P. How CSR Affects Brand Equity of Indian Firms? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, S52–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Rashid, M.A.; Hussain, G.; Ali, H.Y. The effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and firm financial performance: Moderating role of responsible leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Kelly, T.F. B-Corps—A growing form of social enterprise: Tracing their progress and assessing their performance. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenhoefer, L.M. The impact of CSR on corporate reputation perceptions of the public—A configurational multi-time, multi-source perspective. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanathan, P.; van Oosterhout, H.J.; Heugens, P.P.; Duran, P.; van Essen, M. Strategic CSR: A Concept Building Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 57, 314–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pecot, F.; Merchant, A.; Valette-Florence, P.; De Barnier, V. Cognitive outcomes of brand heritage: A signaling perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vogel, D.J. Is there a market for virtue?: The business case for corporate social responsibility. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2005, 47, 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Rodriguez del Bosque, I. CSR and consumer loyalty: The roles of trust: Customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Martínez, J.; Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Currás-Pérez, R. Do Consumers Really Care about Aspects of Corporate Social Responsibility When Developing Attitudes toward a Brand? J. Glob. Mark. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ammar, H.; Naoui, F.B.; Zaiem, I. The influence of the perceptions of corporate social responsibility on trust toward the brand. Int. J. Manag. Account. Econ. 2015, 2, 499–516. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 434–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A Systematic Review of the Corporate Reputation Literature: Definition, Measurement, and Theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, W.; Kirmani, A. A consumer-side experimental examination of signaling theory: Do consumers perceive warranties as signals of quality? J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, S.; Siam, M.R.; Sallaeh, S.B. The impact of CSR on consumers purchase intention: The mediating role of corporate reputation and moderating peers pressure. Int. J. Supp. Chain Manag. 2017, 6, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cornejo, C.; Quevedo-Puente, E.; Delgado-García, J.B. Reporting as a booster of the corporate social performance effect on corporate reputation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1252–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Guerrero-Villegas, J. How corporate social responsibility helps MNEs to improve their reputation. the moderating effects of geographical diversification and operating in developing regions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 25, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of corporate reputation in the airline industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Tsai, Y.H.; Chiu, C.K.; Liu, C.P. Forecasting the purchase intention of IT product: Key roles of trust and environmental consciousness for IT firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2015, 99, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Nishiyama, N. Enhancing customer-based brand equity through CSR in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2017, 20, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S. Nurturing corporate images. Eur. J. Mark. 1977, 11, 120–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; del Bosque, I.R. Exploring the Role of CSR in the Organizational Identity of Hospitality Companies: A Case from the Spanish Tourism Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, B.; Quintana-García, C.A.; Marchante-Lara, M. Total quality management, corporate social responsibility and performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate association and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keller, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R. Brands and Branding: Research Findings and Future Priorities. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L. How effective are your CSR messages? The moderating role of processing fluency and construal level. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lai, K.K. The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand image. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2012, 25, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobri, M.; Diyana, N.; Lennora, P. Building guest loyalty: The role of guest based brand equity and guest experience in resort hotel industry. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2015, 21, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio-García, S.; Prados-Peña, M.B. Do brand authenticity and brand credibility facilitate brand equity? The case of heritage destination brand extension. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spry, A.; Pappu, R.; Cornwell, T.B. Celebrity endorsement, brand credibility and brand equity. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 882–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand credibility, brand consideration and choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, V.; Ali, R.T.M.; Thomas, S. Loyalty intentions: Does the effect of commitment, credibility and awareness vary across consumers with low and high involvement? J. Indian Bus. 2014, 6, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifi, A.; Mostafa, R.B. Brand credibility and customer-based brand equity: A service recovery perspective. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algammash, F.A. The effects of brand image, brand trust, brand credibility on customers’ WOM communication. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2020, 8, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chinomona, R. Brand communication, brand image and brand trust as antecedents of brand loyalty in Gauteng Province of South Africa. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2016, 7, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, J.; Yu, J.H. The differential roles of brand credibility and brand prestige in consumer brand choice. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 662–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. CSR and consumer behavioral responses: The role of customer-company identification. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, L.; Kiessling, T.; Harvey, M. Corporate social responsibility: Why bother? Organ. Dyn. 2014, 43, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, H.; Ruan, W.; Park, Y. Effects of service quality, corporate image, and customer trust on the corporate reputation of airlines. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pineiro-Chousa, J.; Vizcaíno-González, M.; López-Cabarcos, M. Reputation, Game Theory and Entrepreneurial sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Šontaitė-Petkevičienė, M. CSR reasons, practices and impact to corporate reputation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bianchi, E.; Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LaMastra, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy to Repair Brand Reputation. American University. 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1961/auislandora:10367 (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- Jeng, S.-P. The influences of airline brand credibility on consumer purchase intentions. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2016, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z. The effect of brand credibility on consumers’ brand purchase intention in emerging economies: The moderating role of brand awareness and brand image. J. Glob. Mark. 2010, 23, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, H.; Kim, S.S. Consumers’ responses to corporate social responsibility: The mediating role of CSR authenticity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.C.; Monica, F.; Estrella, D.; Silvia, R. Exploring relationships among brand credibility, purchase intention and social media for fashion brands: A conditional mediation model. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 237–251. [Google Scholar]

- Bougoure, U.S.; Russell-Bennett, R.; Fazal-E-Hasan, S.; Mortimer, G. The impact of service failure on brand credibility. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qalati, S.A.; Yuan, L.W.; Jamali, A.B.; Kwabena, G.W.; Erusalkina, D. Brand equity and mediating role of brand reputation in hospitality industry of Pakistan. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Foroudi, P.; Yub, Q.; Guptac, S.; Foroudi, M.M. Enhancing university brand image and reputation through customer value co-creation behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 138, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Melewar, T.C.; Gupta, S. Linking corporate logo, corporate image, and reputation: An examina-tion of consumer perceptions in the financial setting. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2269–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Nguyen, B.; Lee, T. Consumer-based chain restaurant brand equity, brand reputation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, I.; Ahmad, N. Factors of Restaurant Brand Equity and Their Impact on Brand Reputation. J. Mark. Consum. Res. 2018, 46, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, L.; Caruana, A.; Snehota, I. The role of corporate social responsibility, perceived quality and corporate reputation on purchase intention: Implications for brand management. J. Brand Manag. 2012, 20, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.-J.; Park, J.-W. A Study on the Impact of Airline Corporate Reputation on Brand Loyalty. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Sarmento, E.; le Bellego, G. The effect of corporate brand reputation on brand attachment and brand loyalty: Automobile sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozer, E.G.; Civelek, M.E.; Kara, A.S. The effect of consumer based brand equity on brand reputation. Int. J. Eurasia Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, G.; Ulengin, B. Effect of consumer-based brand equity on purchase intention: Considering socioeco-nomic status and gender as moderating effects. J. Euromark. 2015, 24, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.A.; Syed, M.F.; Masood, H.; Waseem, A.S. Impact of brand equity on consumer brand preference and brand purchase intention. IBT J. Bus. Stud. 2019, 15, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Wickham, M. An examination of Marriott’s entry into the Chinese hospitality industry: A Brand Equity perspective. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Tseng, T.-H.; Chang, A.W.-Y.; Phau, I. Applying consumer-based brand equity in luxury hotel branding. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 81, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, P.V.H.; Nguyen, G.T.; Phung, H.T.T.; Ho, T.; Phan, N.T. The relationship between brand equity and in-tention to buy: The case of convenience stores. Interdepend. J. Manag. Prod. 2020, 11, 434–449. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.D. The ethics of branding, customer-brand relationships, brand-equity strategy, and branding as a societal institution. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 95, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardane, N.R. Impact of Brand Equity towards Purchasing Desition: A Situation on Mobile Telecommuni-cation Services of Sri Lanka. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 3, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiville, J.; Hair, J.F.; Cliquet, G. Definition, conceptualization and measurement of consumer-based retailer brand equity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maden, C.; Arıkan, E.; Telci, E.; Kantur, D. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility to corporate reputation: A study on understanding behavioral consequences. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agmeka, F.; Wathoni, R.N.; Santoso, A.S. The influence of discount framing towards brand reputation and brand image on purchase intention and actual behavior in e-commerce. Proced. Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Seock, Y.-K. The impact of corporate reputation on brand attitude and purchase intention. Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Ketchen, D.J.; Wright, M. The Future of Resource-Based Theory: Revitalization or Decline? J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Is the resource-based view a useful perspective for strategic management research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Akar, R.; Presidnet Cyprus Turkish Journalist Union, Nicosia, Cyprus. Personal communication, 12 July 1996.

- Marcoulides, G.A.; Saunders, C. PLS: A Silver Bullet? MIS Q. 2006, 30, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlinger, F.N.; Lee, H.B. Foundations of Behavioral Research; Harcourt College Publishers: Orlando, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Garson, G.D. Partial Least Squares: Regression and Structural Equation Models; Statistical Associates Publishers: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung-Baesecke, C.J.F.; Chen, Y.R.R.; Boyd, B. Corporate social responsibility, media source preference, trust, and public engagement: The informed public’s perspective. Pub. Relat. Rev. 2016, 42, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Henriques, I. Stakeholder influences on sustainability practices in the Canadian forest products industry. Strat. Manag. J. 2004, 26, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Maintaining, Expanding, and Contracting the Organization; Zedeck, S., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- Dabic, M.; Colovic, A.; LaMotte, O.; Painter, M.; Brozovic, S. Industry-specific CSR: Analysis of 20 years of research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I. Measuring consumer perception of CSR in tourism industry: Scale develop-ment and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 27, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Han, T.; Kim, T.; Kwon, S.J.; Del Pobil, A.P. Economic and Environmental benefits of optimized hybrid renewable energy Generation Systems at Jeju National University, South Korea. Sustainability 2016, 8, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The Consumer-Based Brand Equity Inventory: Scale Construct and Validation; GUT FME Working Paper Series A; Gdańsk University of Technology: Gdańsk, Poland, 2014; Volume 4, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.Y.; Hitt, L. Brand awareness and price dispersion in electronic markets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS 2001, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–19 December 2001; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Vukasović, T. An empirical investigation of brand equity: A cross-country validation analysis. J. Glob. Mark. 2016, 29, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.C.; Fortes, N.; Santiago, R. Influence of sensory stimuli on brand experience, brand equity and purchase intention. J. Bus. Econ. 2017, 18, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sahina, A.; Zehirb, C.; Kitapçib, H. The effects of brand experiences, trust and satisfaction on building brand loyalty; an empirical research on global brands. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dwivedi, A.; Nayeem, T.; Murshed, F. Brand experience and consumers’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) a price premium: Mediating role of brand credibility and perceived uniqueness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C.; Moutinho, L. Brand relationships through brand reputation and brand tribalism. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudeshia, C.; Kumar, A. Social eWOM: Does it affect the brand attitude and purchase intention of brands? Manag. Res. Rev. 2017, 40, 310–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lee, S. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. Impact of interpersonal influences, brand origin and brand image on luxury purchase intentions: Measuring interfunctional interactions and a cross-national comparison. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Variable | Frequency (N = 380) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 219 | 57.6 |

| Male | 161 | 42.4 | |

| Age | Under 15 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 15–25 | 171 | 45 | |

| 26–35 | 95 | 25 | |

| Over 35 | 112 | 29.5 | |

| Education | High school diploma | 12 | 3.1 |

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent | 267 | 70.3 | |

| Master’s degree or equivalent | 90 | 23.7 | |

| PhD or equivalent | 11 | 2.9 | |

| Monthly income | Less than 10 million dong | 217 | 57.1 |

| 10–20 million dong | 108 | 28.4 | |

| More than 20 million dong | 55 | 14.5 | |

| Frequency of buying cosmetic products | Once a year | 107 | 28.2 |

| Every 3 months | 108 | 28.4 | |

| Every 6 months | 98 | 25.8 | |

| Once a month | 47 | 12.4 | |

| More than once a month | 20 | 5.2 | |

| Total | 380 | 100 | |

| Variable | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR | 0.534 | 0.937 | 0.927 | |

| BE | 0.615 | 0.971 | 0.969 | 0.390 |

| BC | 0.697 | 0.902 | 0.855 | 0.418 |

| BR | 0.678 | 0.894 | 0.842 | 0.639 |

| PI | 0.763 | 0.906 | 0.839 | 0.613 |

| Fornell–Larcker Criterion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | BE | BR | CSR | PI | |

| BC | 0.835 | ||||

| BE | 0.498 | 0.785 | |||

| BR | 0.677 | 0.650 | 0.824 | ||

| CSR | 0.625 | 0.624 | 0.705 | 0.731 | |

| PI | 0.630 | 0.678 | 0.701 | 0.588 | 0.870 |

| HTMT criterion | |||||

| BC | |||||

| BE | 0.546 | ||||

| BR | 0.796 | 0.720 | |||

| CSR | 0.701 | 0.657 | 0.796 | ||

| PI | 0.743 | 0.752 | 0.834 | 0.665 | |

| BC | BE | BR | PI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC | 1.640 | 1.692 | 2.005 | |

| BE | 1.718 | 1.958 | ||

| BR | 2.770 | |||

| CSR | 1.000 | 1.640 | 2.111 | 2.376 |

| Hypothesis | Path | f2 | Standardized Estimate | t | p | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CSR → BC | 0.640 | 0.625 | 13.095 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | CSR → BR | 0.126 | 0.309 | 5.627 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | CSR → BE | 0.287 | 0.526 | 10.628 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4 | BC → BE | 0.032 | 0.173 | 3.528 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | BC → BR | 0.185 | 0.337 | 8.150 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6 | BE → BR | 0.139 | 0.293 | 6.735 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H7 | BC → PI | 0.081 | 0.262 | 6.189 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H8 | BE → PI | 0.183 | 0.358 | 7.925 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H9 | BR → PI | 0.081 | 0.314 | 6.013 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Direct and Indirect Path | Standardized Estimate | t | p | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR → PI | −0.011 | 0.285 | 0.776 | Insignificant |

| CSR → BC | 0.625 | 12.962 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BC → PI | 0.251 | 5.768 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BC → PI | 0.164 | 5.432 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → PI | −0.011 | 0.285 | 0.776 | Insignificant |

| CSR → BE | 0.524 | 11.254 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BE → PI | 0.372 | 7.996 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BE → PI | 0.188 | 5.964 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → PI | −0.011 | 0.285 | 0.776 | Insignificant |

| CSR → BR | 0.309 | 5.695 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BR → PI | 0.295 | 4.971 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BR → PI | 0.097 | 3.803 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BR | 0.309 | 5.695 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BC | 0.625 | 12.962 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BC → BR | 0.336 | 8.121 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR→ BC → BR | 0.210 | 3.239 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BR | 0.309 | 5.695 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR → BE | 0.524 | 11.254 | 0.000 | Significant |

| BE → BR | 0.294 | 6.663 | 0.000 | Significant |

| CSR→ BE → BR | 0.154 | 5.647 | 0.000 | Significant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Liao, Y.-K.; Wu, W.-Y.; Le, K.B.H. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions in Brand Equity, Brand Credibility, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111975

Wang S, Liao Y-K, Wu W-Y, Le KBH. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions in Brand Equity, Brand Credibility, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intentions. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111975

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shu, Ying-Kai Liao, Wann-Yih Wu, and Khanh Bao Ho Le. 2021. "The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions in Brand Equity, Brand Credibility, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intentions" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111975

APA StyleWang, S., Liao, Y.-K., Wu, W.-Y., & Le, K. B. H. (2021). The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility Perceptions in Brand Equity, Brand Credibility, Brand Reputation, and Purchase Intentions. Sustainability, 13(21), 11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111975