Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 evoked a heated discussion of its drivers and extensive impacts on achieving sustainable development goals. Considering the deepening global interconnectedness and complex human–environment interactions, it calls for a clarity of the two concepts of risk governance and sustainability and their relationships. In this paper, a comprehensive review was provided based on scientometric analysis. A total number of 1156 published papers were studied and a considerable increase of interest in this line of research was found. The research outputs show the interdisciplinary feature of this field but with a focus on environmental issues. The journal “Sustainability” was found to be the most productive journal. Geographic and institutional focus on the line of research were also visualized. Five salient research themes were identified as follows: (1) Resilience and adaptation to climate change; (2) Urban risk governance and sustainability; (3) Environmental governance and transformation; (4) Collaborative governance and policy integration; and (5) Corporate governance and sustainability. This paper provides insights into the heterogeneity of the risk governance and sustainability research. Additionally, the study unveiled the implicit relationship linking risk governance and sustainability: risk governance can be a process of participation and coordination, and a means of coping with the uncertainty and complexity to achieve sustainable outcomes. On the other hand, risk governance is a constant aim to be optimized in the process of sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Both the concepts of risk governance and sustainability have gained worldwide attention, not only in scientific research, but also in policies and practices. The COVID-19 pandemic, described by the United Nations as the biggest challenge the entire human race has faced since World War II [1], has significantly slowed the international community’s progress towards sustainability [2]. The global health crisis has immensely impacted the economic, environmental, and social pillars of sustainability [3]. The priority of achieving the 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) has been greatly reduced despite being more critical than ever [4]. Such an unpredictable event illustrates the deepening global interconnectedness, the importance of governance in controlling the pandemic and recovering from it, and its cascading outcomes from the health system to the economy and human well-being. The limitations of human systems to deal with the changing environment have become apparent. Can we be adequately prepared for a next pandemic or other unforeseen extreme events? There is little choice but for humans to intervene in multiple, interconnected, and complex systems (e.g., healthcare, economy, environment, society) in a collaborative way, particularly for the systemic risks [5]. Governing risks in a systematic way and dealing with the risks at source would be a window of opportunity for cost-effective sustainable transitions.

Several studies have been published to map the global research of sustainability [6], to address the relationship between sustainability and governance [7], the relationship between sustainability and corporate social responsibility [8], the progress towards sustainability and well-being [9], and the landscape of risk communication research to support risk governance [10]. However, the literature relating to the intersection field of risk governance and sustainability is fragmented. The relationship between the two concepts has been rarely discussed. In this study, we attempted to complement the clarity of the relationship in a systematic way. Firstly, based on the scientometric analysis, we present the development of scientific production in the line of research. Secondly, we visualize the geographic and institutional feature of the research. Then, we identify key research themes in the academic literature associating the two concepts, providing semantic constellations to present the heterogeneity of the line of research. Finally, after describing the five research themes in detail, the relationship between risk governance and sustainability is discussed.

2. Data and Method

To investigate historical developments in the research intersection of risk governance and sustainability, the relevant articles published in academic journals were searched in the Web of Science Core Collection. We searched for combinations of relevant keywords shown as follows:

Topics = (“Sustainabilit*” and Risk Governance);

Language = English;

Subdatabases = SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH;

Time span = all years.

Each article in the electronic databases that contains the key search words in either its title or abstract was included. We found 1156 published papers from 1998, until 6 July 2021, when the data were collected. Among the papers, 959 were research articles, followed by 107 proceeding papers and 90 review articles.

The scientometric techniques have been widely used in the domain of knowledge analysis, especially in review research [11]. In our research, the VOSviewer software was used to generate the collaboration networks, and to show the leading countries/regions and institutions in ‘risk governance and sustainability (RGS)’. The keyword co-occurrence networks were also analyzed, and used to show the research hotspots and research groups of the RGS. VOSviewer was developed by Nees and Ludo [12] from the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (Leiden University), with more than 10 years development and update. It has become one of the most reliable and widely-used scientometrics tool in the global scientific communities.

3. The Landscape of Risk Governance and Sustainability Studies

3.1. Overview of Scientific Productivity in the Intersection Field

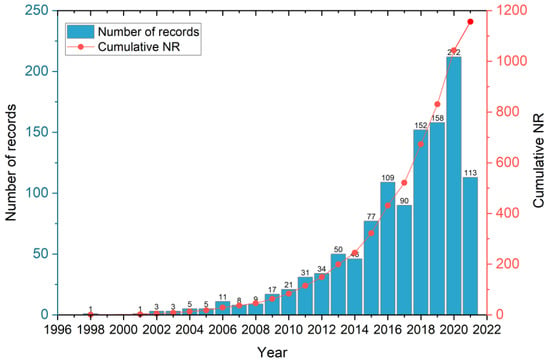

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 1156 published papers in the risk governance and sustainability domain from the year 1998 to 2021. The first related paper was in 1998, which was presented at the Conference on Twice Humanity—Implications for Local and Global [13]. It discussed the direction of agricultural research in Africa to call for a sustainable solution under disadvantaged conditions. Since 2014, there was a rapid increase of research activities; crossing 100 articles per year in the year 2016 and subsequently crossing 200 articles per year in 2020 (with the most paper outputs of 212).

Figure 1.

Annual publication productivity in the field of risk governance and sustainability.

The categorization of the 1156 papers in scientific disciplines can be provided by the Web of Science, which provides insights into how the target research domain situates in the entire body of scientific knowledge. Based on the analysis, the most frequently occurring scientific categories are “environmental sciences and studies” with 786 papers amounting to 68% of the total. The following categories are “sustainable science and technology” (264 papers), “management” (110 papers), “business” (97 papers), “economics” (71 papers) and others. The research area involved is quite diverse, not only covering engineering and natural sciences (e.g., geography, geosciences, medicine), but also humanities and social sciences. There is no surprise, considering the risk governance research and sustainability research do encompass a variety of issues.

The top five source journals are “Sustainability” (142 papers), “Journal of cleaner production” (39 papers), “Global environmental change” (20 papers), “Environmental science and policy” (20 papers), and “Ecology and society” (19 papers). The journal “Sustainability” was found to provide important space for sustainability research and interdisciplinary research.

3.2. Networking of Countries and Institutions in the Research Domain

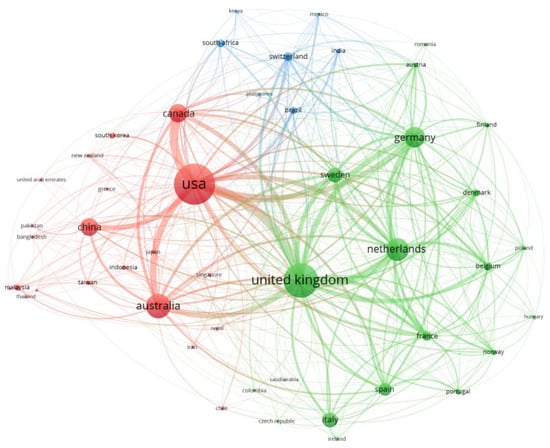

Authors from 101 countries were found to contribute to the research field, which cover all continents of the world. Table 1 lists the top 20 countries with paper outputs of over 20. The top five countries, which have the most outputs in the field are the US, UK, Australia, the Netherlands, and Germany. From the figure of national/regional cooperation network (Figure 2), we could see a network of relatively high density between countries/regions. Consistent with the conclusion that the UK and US are the leading countries in the international collaborations, the US and UK stand as the core positions in the entire network, communicating frequently with others. The US, which has published the most papers of 255 in total, cooperates closely with the UK, Canada, Australia, and China. Besides the close cooperation between the UK and US, the UK has stronger links with other European countries, such as the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany.

Table 1.

Top 20 countries contributed to the research field of risk governance and sustainability.

Figure 2.

Cooperation network of Countries/Regions.

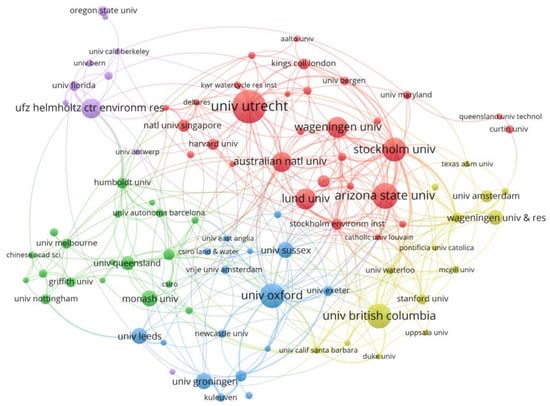

National/regional cooperation depends on research institutions to exchange knowledge with each other. As shown in Figure 3, Top 5 institutions with the most outputs in the field are University of Utrecht (The Netherlands), Arizona State University (US), University of British Columbia (Canada), University of Oxford (UK), and Stockholm University (Sweden). The actual difference in number of publications between them is small. In this intersection field, University of Utrecht published 27 papers in total, Stockholm University published 19 papers, and Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research (Germany) published 16 papers.

Figure 3.

Cooperation network of research institutions.

4. Identification of Salient Research Themes

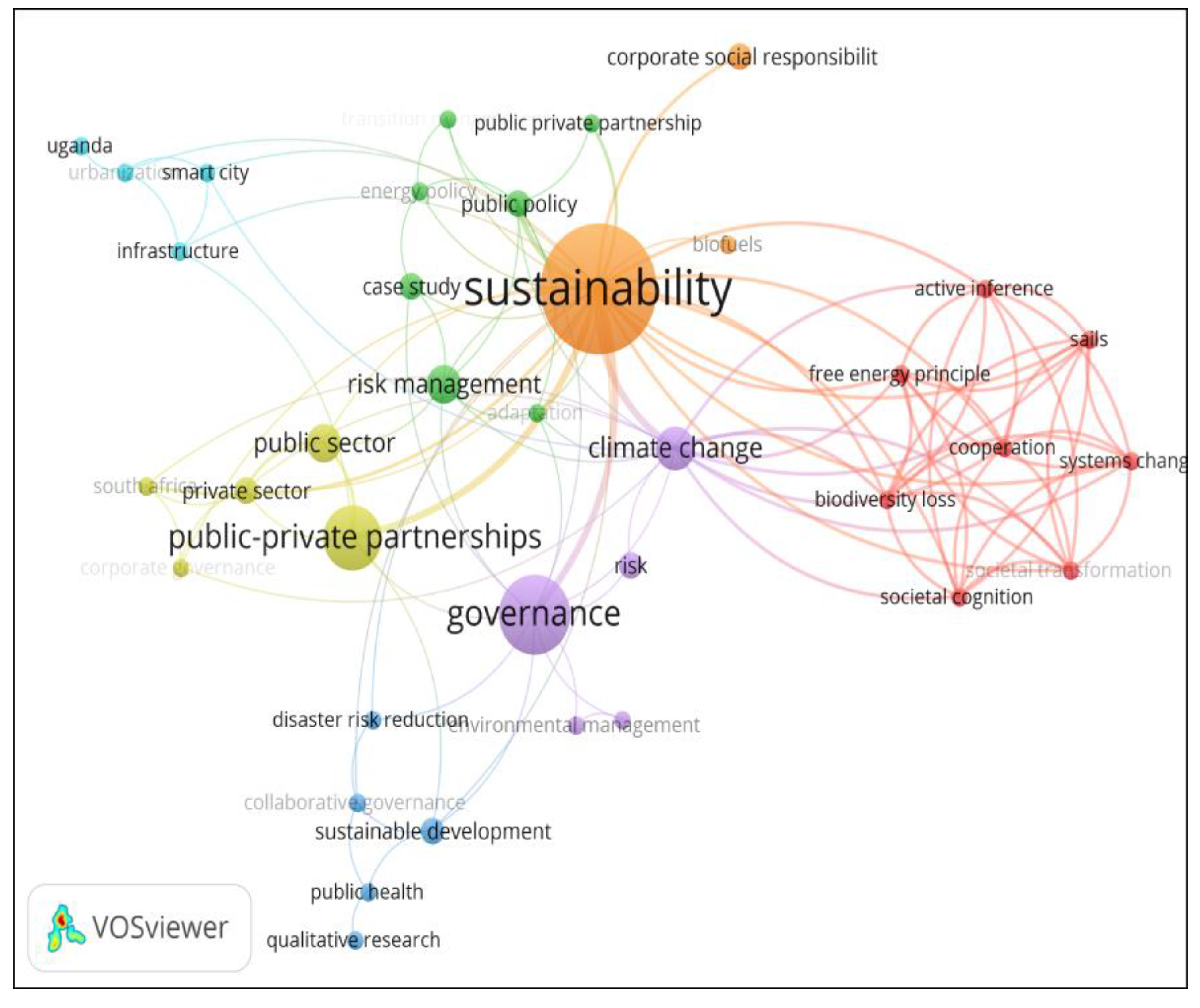

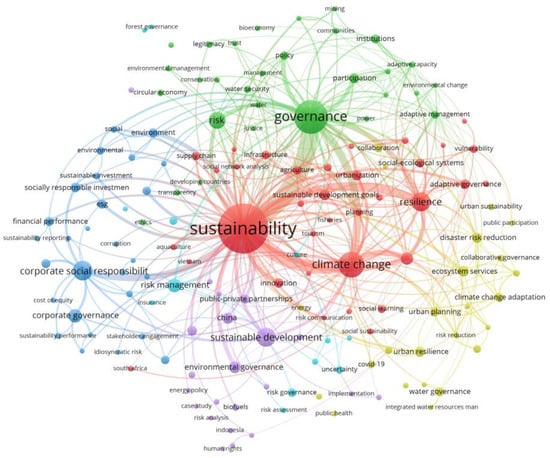

The cluster analysis provides hints about research interests in the dataset. The 1156 papers address a variety of issues. As shown in Figure 4, “Sustainability” and “Governance” have gained prominence in the keywords. Five salient research themes emerged from these articles and will be described below in more detail.

Figure 4.

Keyword clusters of the risk governance and sustainability research.

4.1. Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Change

Climate change is one of the most threatening environmental problems. Climate actions are aligned with the 13th sustainable development goal of taking urgent action to combat climate change. Considering uncertainty is an inherent feature of climate change, adaptive governance can be a promising approach to reduce uncertainty by improving the knowledge base for decision making [14]. Adaptive governance is a continuous problem-solving process “by which institutional arrangements and ecological knowledge are tested and revised in a dynamic, ongoing, self-organized process of learning by doing” [15]. Ortwin Renn proposed ‘precaution-based’ and ‘resilience-focused’ strategies for managing uncertain risks [16]. The former strategies aim at accessing the best available scientific expertise and reducing a system’s vulnerability to known hazards, while the latter strategies aim at applying a precautionary approach in order to ensure the reversibility of critical decisions and increasing a system’s coping capacity to surprises.

Climate change risks involve risk sources and consequences from several sectors and many fields, such as agriculture, fishery, drought and flood, ecosystem function, health risks and climate-sensitive industry risks [17]. The approach to divide the risk assessment into individual sectors, regions, types of response options, etc. and then synthesizing thousands of discipline-specific studies is often used. However, multiple complexities arise from interactions across sectoral, temporal, spatial, and response-option boundaries. Interactions among these risks caused by climate change or interacting drivers of the climate change risk, and interactive response actions towards climate change among sectors and systems may amplify or reduce climate-related risks [18].

Climate change calls for a global response, as human activities have become globally interconnected and intensified through new technology and capital markets in the globalization. Hierarchical government in domestic politics as well as international regimes in international politics lose some explanatory power, instead, multi-level governance and global governance are being called on to address this issue. The IRGC (International Risk Governance Council) risk governance framework brought forward by Ortwin Renn can be used to address and respond to such a global risk and design appropriate governance strategies in a structured way [19]. The risk categorization and fitting management approach in the IRGC risk governance framework is often cited. Based on the knowledge states of the cause–effect relationships and the potential consequences, whether the evaluation method is scientific or value-based, risks can be categorized as ‘simple’, ‘complex’, ‘uncertain’, and ‘ambiguous’ [16]. Then, corresponding management strategies can be proposed after allocating the risk classes.

As a result of its non-linear effects, full of uncertainties and complexities, and ambiguities about response options, we cannot trace the effects of climate change back to clear and transparent decisions. Rather, it is the co-evolution of science, industry and politics engaging in the risk. To combat climate change, addressing the social or ecological systems alone from a steady-state view will be far from sufficient to achieve sustainable outcomes. The complex social-ecological systems pose great challenges to the governance, which demands working across scale and nested governance horizontally and vertically, collaboration across boundaries from local to international, and creating institutional arrangements that adapt to change and maintain resilience in a dynamic environment [20]. It requires the organizational and institutional flexibility to deal with uncertainty and changes. Social capital and governance experience of dealing with changes also contribute to the capacity of social-ecological systems to adapt to and shape changes [15]. Even if the system is near to lose resilience, as long as there is adaptive capacity to respond to the change and possibly restore it, then the system is still resilient. Climate change calls for more adaptive governance regimes to deal with its inherent uncertain and complex features. Meanwhile, it should integrate risk governance, as risk reduction by adaptation to variable weather seems inevitable, and the framing and perceptions of the ‘risk’ stymies adaptive governance [21]. Political structures may mobilize and take advantage of the advanced scientific tools and methodologies for calculation, scenario analysis, forecasting and simulation. Methodology on nexus approaches to sustainable development, which simultaneously examine multiple sectors, is demanding [22]. Policy diffusion of eco-innovation and green technologies is a critical tool for sustainable development [23]. Climate governance could also benefit from systematic and flexible decision-making tools, such as participatory multicriteria methods for the evaluation of adaptation options [14].

4.2. Urban Risk Governance and Sustainability

Urbanization is a major global development. Countries all over the world face increasing flood risks due to urbanization and climate change [24]. Together with other geophysical and social forces interacting with urban systems, natural disasters, social risks, industry accidents and other extreme events (including climate-related events and epidemiological events) also affect cities in terms of economic losses and health consequences, as well as on the environment. The effects may be mediated by location, scale, density, or connectivity, and also involve feedback loops and cascading outcomes [25]. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, has resulted in great economic losses, human deaths and unemployment, restricted mobility as well as rapidly augmented medical waste. Besides the possibility of interactions among multiple risks and worsened effects caused by global connectivity, cities with dense population in limited areas must face the problem of altered land use, resource scarcity (e.g., water, energy), air pollution, water pollution and large amounts of waste for treatment, plus asymmetric distribution problems. Moreover, not only do cities face multiple risks in how they are being affected, the urban system as part of the whole ecosystem, exerts impacts on the wider environment in which urbanization is a typical factor. Therefore, if cities are well managed, it can significantly improve the scale of consumed resources and impacts on the ecosystem. Scholars thus suggest various risks (e.g., natural hazards, technological risks, social risks and financial risks) need to be considered in the urban planning phase [26]. Well-planned urban density and convenient urban services can benefit residents’ well-being, improve energy efficiency and decrease pollutant emissions [25]. Recently, there has been a surge of interest in nexus governance to encompass a broad understanding of governance in terms of political, social, economic, and administrative systems that determine the use of resources and related service delivery across sectors. Although the concept and how to implement it are still vague, “governance” is treated more as “recommendations” integrating different concepts of governance theory, such as sustainable development, environmental governance, urban governance, integrative and cooperative governance and transdisciplinary governance, to address complexities, uncertainties, and ambiguities [27].

The complex ways in which urban systems interact with climate change and other driving forces lead to cities being vulnerable to natural disasters, terrorism attacks, and other extreme events. The application of information technologies in cities heatedly discussed by the public, involves a mixture of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity, which may cause unexpected consequences. It entails not just technical aspects, but demands a socio-technical transition when adopting smart technologies or green initiatives. Particularly, the above risks cannot be dealt with in isolation [28]. An integrated and systematic approach, such as the risk governance framework, is necessary. The risk governance framework asks for permanent adjustment and improvement, which can improve the resilience of the cities’ social-ecological systems, and thereby contributes to the overall sustainability of the urban development [26]. In addition, short-term and long-term causal chains and feedback loops should be captured if possible, to identify critical leverage points in case of cascading effects. Institutional diversity to complement separately constituted public bodies with fragmented jurisdictions can be an advantage when dealing with transboundary risks, such as the diversity of urban water regimes in Europe [29], and the river chief system from Chinese practices [30]. The application or innovation should fit to the local cultural contexts [31].

From the perspective of risk governance, the implementation steps are not limited to mapping the urban risks and coming up with integrative control measures by involving expertise from scientists in diverse background, urban planners, engineers and decision makers in urban governance, participatory planning and stakeholder communication are deemed helpful in the whole process. The suggested actions include improved risk screening, early warning systems of threats, sustainable urban planning with appropriate infrastructure design, regulatory mechanisms to encourage sustainable growth, and resilient disaster management systems. The selection of management options is dependent on risk characteristics [28].

4.3. Environmental Governance and Transformation

Today’s sustainability policy is rooted in environmental policy, after the side effects of industrialization become clear and environmental problems become a global issue. Earlier sectoral environmental policies with focus on cleaning up environmental pollution were not sufficient to tackle interconnected environmental problems. Then, “sustainable development” responded to the question as well as social and economic development challenges. Since the 1990s, sustainability policy has gone beyond environmental policy, from the local to the international level. Recently, with regard to a call for cosmopolitan policymaking on sustainable development, earth system governance, which treats the entire earth system as an integrated object of political efforts, has been developed [32]. The nonlinearity of processes, complex interrelationships between components of earth system, and the fast-growing role of humans are making the earth fragile [33]. Earth system governance emphasizes societal steering of human activities for the long-term stability of the system under the cooperation between natural sciences and social sciences, with shared interests in the exploration of how to reform the ways of human societies steering their co-evolution with nature. The research alliance put forward a joint analytical framework revolving five dimensions of effective governance, which are: agency in earth system governance, the overall architecture of earth system governance from local to global levels, the accountability and legitimacy of earth system governance, the allocation problem in earth system governance, and the overall adaptiveness of individual governance mechanisms, processes and the governance system [32,34].

For the environmental issues, the feature of cross-scale has been recognized. Management of common resources in large scales pose great challenges and the costs should be internalized. Environmental risks are associated with social and economic development, and interconnected with human activities and policy making. Economic efficiency, environmental effectiveness, equity, and political legitimacy are important dimensions of sustainable development and also core outcomes of environmental governance [35]. The environmental system itself is complex whose behavior is variable, nonlinear, and at times chaotic. In addition, there are complex interactions of changing social and environmental systems with too many variables and causal paths. Environmental disasters occur from constellations of hazards that overwhelm societal response capabilities. Cognitive and organizational obstacles among decision-makers could result in lack of preparedness for environmental crises [36]. Stakeholder participation assists decision-makers in identifying public interest concerns, promotes environmental justice and enhance accountability and acceptability of environmental decisions, and therefore improves the adaptive capacity [37]. Actors participating in decision-making in diverse arenas (e.g., local politics, national politics, scientific research, the media, multilateral environment agreements) are constituted by institutions, which define their rights, responsibilities, and power; they have different knowledge, expertise and perceptions about the natural, economic and social aspects [35]. Preferences and cultural diversity may hinder the sharing of interests and understandings. Developing policies combating environmental risks following the risk governance framework could support the integration of risk knowledge, identify opportunities for improvement and lead to more effective and acceptable outcomes.

Is there a third way between environmental degradation and persisting under-development? A much-needed third way could be a co-generated transformation by political leaders, business executives, and civil society to re-invent the industrial metabolism [38]. Transformation towards sustainability has been obtaining the attention, not only in global sustainability research, but also policy discourse in recent years [39,40,41]. Social-ecological systems scholars, transition scholars, development scholars, and political scientists have different focus to understand the transformation [42]. In general, they propose that transformations are complex, dynamic, and involve change in multiple systems (e.g., social, political, economic, technological, ecological). Transformation towards sustainability involves changes across multiple levels (e.g., geographical, institutional, temporal). Trajectories of transformative change cannot be viewed in a narrow disciplinary-bounded way, but may emerge from co-evolutionary interactions between multiple systems [42,43]. Different types of governance activities, such as strategic, tactical, operational, and evaluation-oriented activities, occur simultaneously in the transformation processes. Each has its own dynamic, type of actors, and impact in different phases, and they influence each other [44].

4.4. Collaborative Governance and Policy Integration

The IRGC risk governance framework advocates inclusive governance, particularly with respect to global and system risks [19]. Stakeholders are not only risk producers, their knowledge, preferences, and interests also have influences on the mitigation. Depending on the risk classes allocated according to the quality and nature of available information, different types of audiences need to be involved in a variety of forms and procedures in the process of framing the problem, generating, and evaluating options, and in drawing a joint conclusion. Inclusion and selection are two essential parts of decision- or policy-making activities. The participatory procedures should consider basic features, such as transparency, competence, fairness, efficiency, clear mandate, diversity, and professionalism. Pools of instruments for stakeholder participation provide sufficient choices for the corresponding risk problem at hand, to cope with complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity [16].

Dealing with complex, uncertain, and controversial outcomes often leads to conflicts. Risk governance is of particular importance in situations where there is no single authority to make the decision, while the nature of the risk requires the collaboration of, and coordination between a range of different stakeholders [16]. Therefore, it is recommended to use multi-criteria or multi-attribute decision-analytic models to identify potential conflicts between objectives and assign tradeoffs [28]. Collaborative governance can also bring public and private stakeholders together to reach consensus-oriented decisions, and private preferences can be aggregated into collective choices [45]. Collaborative approaches in adaptive governance provide cross-scale linkages between actors, facilitate learning while sharing rights and responsibilities, and support flexible governance when faced with complexity and uncertainty. However, not all collaborations become successful or come to agreed-upon outcomes. There are challenges in the collaborative process, such as trust, competition, different operation modes, conflicting mandates, access to resources, and power imbalances among actors [46]. Accountability also entails whether a collaboration is meeting its objectives, first via the articulation of goals, and then via the operationalization of those goals [47]. Institutional arrangements are called for to facilitate collaborative research and knowledge sharing across discipline boundaries, which is quite important to understand the complex social-ecological systems with resource nexus and systemic risks involved [48].

Moreover, poorly integrated public policies will erode the quality of governance as well, particularly environmental problems require responses that transcend the usual functional divides of government actions [49]. Policies in different sectors with divergent goals could have tradeoffs instead of synergies. Effective coordination is instrumental for policy making in complex policy areas. Integrated environmental management should embrace top-down, bottom-up and middle-out initiatives, but in reality it is more like fragmented sets of practices with little coordination [49]. One central element of sustainable development is the integration of environmental objectives into non-environmental policy sectors. After tracing the history of environmental policy integration (EPI) as a guiding principle, Lafferty and Hovden [50] found that different policy documents interpret EPI differently. Instead of reconciling economic, social priorities with regard to environmental degradation, the policy ‘cohesion’ guides the direction. The OECD emphasized EPI to achieve mutual benefits, while the EU stressed all sectors to comply with EPI to integrate environmental concerns into other policies, and many national governments think of it as strategies, plans, instruments or initiatives to promote ecologically sustainable development. In fact, three criteria need to be satisfied when a policy is to be integrated: comprehensiveness, aggregation, and consistency [51]. Policy integration provides a bridge for the environmental policy making, incorporating environmental objectives into all stages of policy making in non-environmental policy sectors, and aggregating presumed environmental consequences into an overall evaluation of policies [50]. In particular, vertical EPI allows individual sectors to freely develop the concept and integrate environmental concerns in their activities. It pursues changes without a formal strategic plan from upper level, then the environmental objectives easily become fragile as sectoral departments must compete with daily dominant interests of traditional policy makings. Horizontal EPI indicates a central authority has developed a comprehensive cross-sectoral strategy for policy integration. Then, the conflicted objectives can be communicated through various legal-administrative instruments, both within and across sectors, which entails much more than policy coordination [50]. The prominence of climate change led to heated discussion about climate policy integration, as a process of coordination, or as a set of policy outputs [52]. Hogl et al. suggest policy integration as a ‘policy design’ approach, which can combine policy elements to tackle complex policy problems, which span out of the existing subsystems [52]. Policy integration as a ‘governance’ approach, which is a process that needs to be steered and identify the forces of integration. It may successfully span the boundaries of existing policy subsystems to tackle cross-cutting policy problems. Nevertheless, policy integration work is still in its infancy. Collaboration governance facilitates horizontal communication among multi-actors, while policy integration is important to solve the interdependency between norms of sustainable development and implementation in sector-specific contexts. For example, the “green economy” cannot be achieved without the integration of financing, environment, innovation, and other sectoral policies.

4.5. Corporate Governance and Sustainability

The 2008 financial crisis reflected the underlying morphology of randomness could create a flawed risk culture. The financialization of the economy without considering environmental constraints has caused considerable damage to the environment and has been inherently dangerous for the sustainability of the economy [53]. Financial institutions in particular play a significant role in ensuring sustainable economic growth [54]. Whether they incorporate environmental and social considerations into their risk management systems not only reflect their values when faced with shareholders, but also express their commitment to sustainable development with a broader concern. In addition, problems arising from company complexity are not unique to transnational banks. Non-financial firms cannot be excluded due to technology sharing, out-sourcing, and interconnections in the supply chains. There is not one solution to address weaknesses in financial and non-financial company’s corporate governance practices [55]. As a holistic approach, corporate governance with the integration of effective risk management to manage business affairs could protect the interests of shareholders along with considering the interests of other stakeholders [56].

There are some empirical studies focusing on the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial risk [57,58,59]. CSR is “a concept through which companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their commercial operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” [60]. Improved CSR not only leads to value enhancement beyond legislative guidelines, to a transparent style of resource management that guarantees expected results (e.g., economic, social, environmental aspects), but also to a persistent reduction in the risks it faces [8,61,62,63]. A virtuous circle between CSR and financial risk is corroborated, that is, strong CSR engagement reduces the firm’s actual financial risk, and this lowering stimulates corporate social performance. Social and governance commitments tend to reduce financial risk more significantly than environmental engagement, which requires expensive and long-term investments [64]. Other relevant research in this cluster includes a number of specific subfields, such as decision-making processes of applying sustainable or social responsible practices [65], sustainable supply chain management [66,67], performance of sustainability indicators [68], the impact of ties to the government and policy uncertainty [69,70], and public–private partnerships [71].

Corporate sustainability can be measured by dimensions of societal influence, environmental impact, organizational culture, and financial aspects. The firm performance is highly dependent on corporate governance, for which there are four principles of good governance for practice: transparency, accountability, responsibility, and fairness. These four aspects are related to corporate social responsibility [72]. Companies with better CSR performance differentiate themselves from others [73]. CSR enables them to address and mitigate reputational, strategic, operational, compliance and financial risks [74]. Media coverage of corporate social irresponsibility may lead to higher financial risk because it increases the potential for stakeholder sanctions [75].

As environmental initiatives are gaining more attention worldwide, more firms are adopting sustainable strategies and disseminating information about their activities and impacts on the environment [76]. A significant negative association between corporate risk-taking and environmental disclosure quality has been found. Corporate governance practices in developing countries can moderate the relationship between the two. Good corporate governance characteristics can decrease the firm risk along with environmental reporting [77]. Environmental disclosure is seen as a way of exhibiting firms’ social responsibility. Their disclosure decisions, to enhance the environmental legitimacy, are more likely to be influenced by stakeholders’ demands for information concerning environmental risks, particularly when sustainability practices are more rewarding in the market [78].

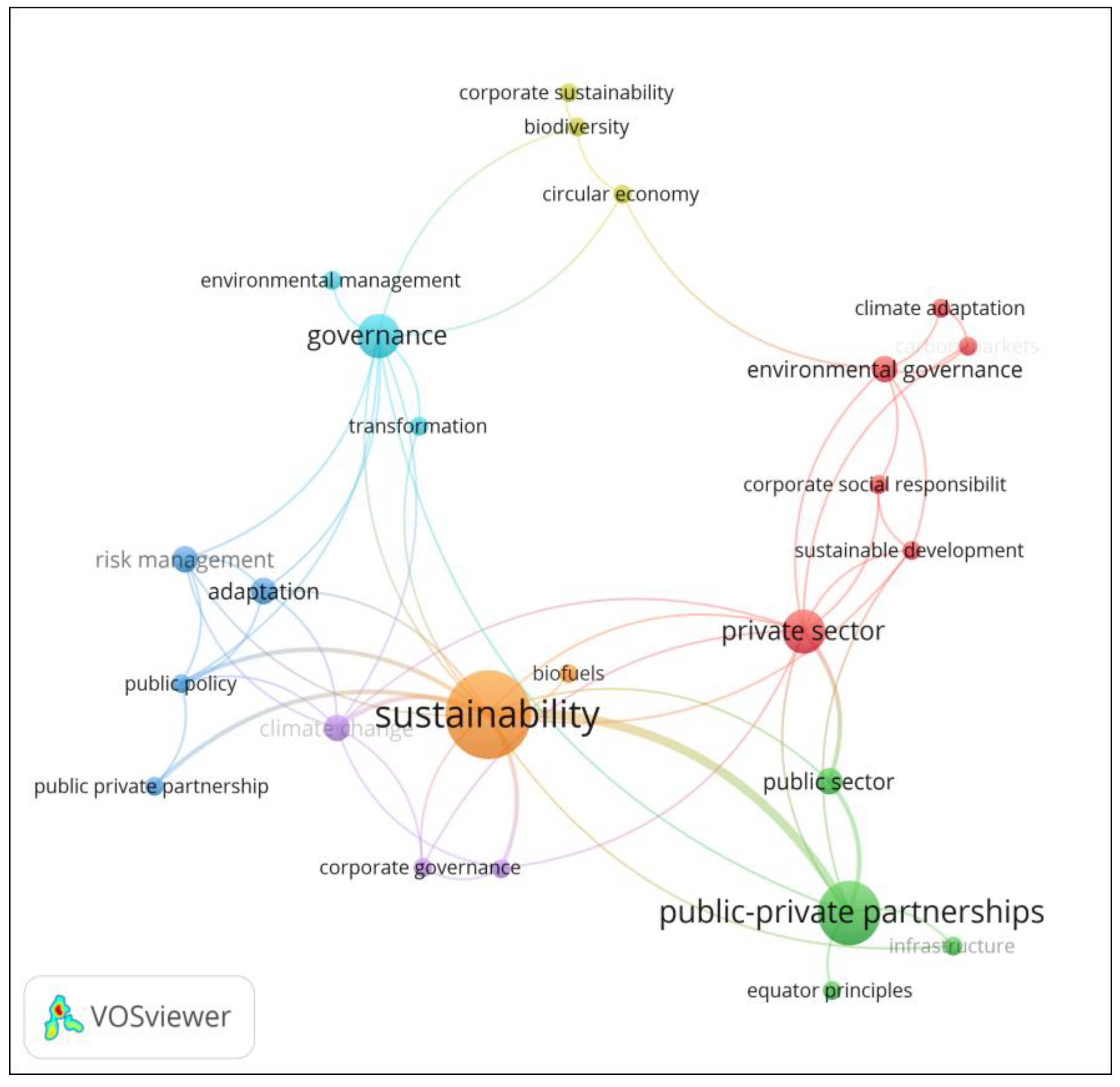

5. A Relational Perspective Addressing Sustainability-Related Objectives

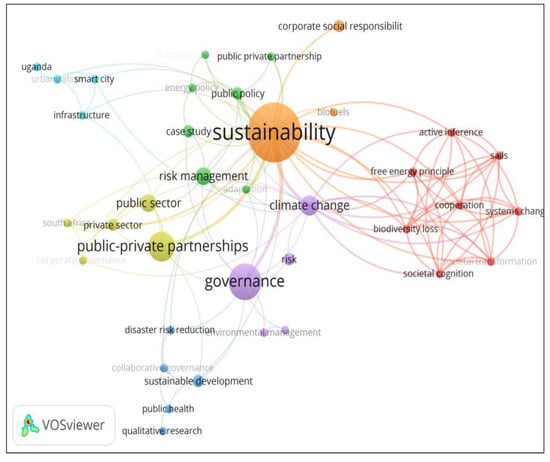

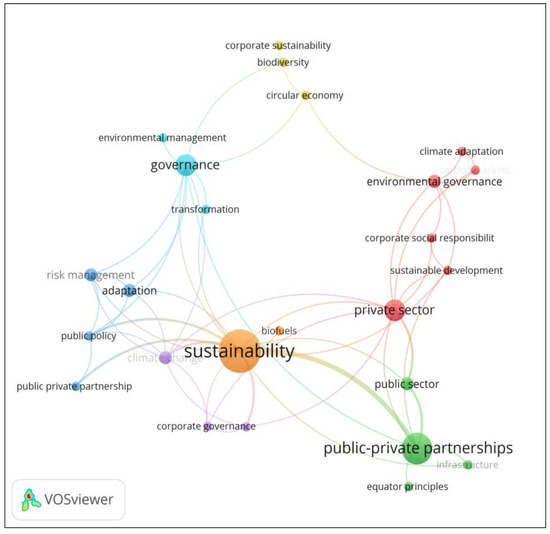

Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the different findings regarding the public and private sector. Besides two main streams of research in sustainability and governance, public–private partnerships are important connections to the other sub-topics, such as environmental governance, corporate sustainability, risk management and adaptation. This is the same for the two figures. Different is, Figure 5 presents a state-led roadmap for sustainable development, while Figure 6 illustrates those areas where private sector actors have been conspicuously involved. In further comparison, Figure 5 emphasizes cooperation, collaborative governance, policy, risk reduction and system change, while Figure 6 emphasizes corporate governance, circular economy, and environmental management. Public sector and private sector actors have different motivations and capabilities for sustainability. The former focuses more on encouraging both public and private sectors to invest in risk reduction and adaptation by effective policies to achieve sustainable development. The latter focuses more on feasible practices and risk management measures, thereby exhibiting strategic outlooks to stakeholders and ensuring sustained growth.

Figure 5.

Keyword clusters of the risk governance and sustainability research related to the public sector.

Figure 6.

Keyword clusters of the risk governance and sustainability research related to the private sector.

To achieve sustainable development goals, public sector actors can deploy regulations and guidelines shaping the industry activities and how people live their lives. Private sector actors could mobilize political will and resources, transfer technology, and adapt their businesses to address socio-ecological challenges. More than ever, the private sector should play a fundamental role in advancing SDGs, which will redirect private investments responsibly, aligning their strategies and delivering business solutions to contribute [79]. In addition to promoting sustainable industrialization and fostering innovation, private sector financing is necessary to complement scarce public funding. Since the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, the private sector has become much more important in PPPs (public–private partnerships), to ensure the public service is provisioned in a more sustainable and efficient way [80]. Best practices, such as corporate social responsibility and the Equator Principles, enable companies to deal with the trade-off between self-interest and socio-environmental consequences [81]. SDG 17 calls for global partnerships, with a focus on the capacity of companies as partners contributing to various areas, such as education, health, urban development, donations, and cross-sector collaborations, with governments, academia, and civil society [82]. In that way, governments need to provide the enabling multi-stakeholder environment, bolstering the legitimacy of domestic policy processes but not hampering actions due to diversity in norms and lack of mutual understanding. The real transformative change demands whole-of-society efforts in the long run. Collaborations across scales and sectors, adaptive governance with updating knowledge and flexible arrangements, have been described in the above analysis as critical in dealing with global problems, such as climate change, while public–private partnerships are the important glue for the SDG implementation. Empirical studies indicate that PPPs have been applied in many fields, such as infrastructure (e.g., water, energy, transportation), education, healthcare, urban development, waste management and so on [80]. The social objectives addressed by PPPs include empowerment, equity, accountability, and transparency [80]. As for the environmental dimension, PPPs can contribute to the diffusion of renewable energies [83]. The economic objectives include cost-saving, risk transfer, efficiency, and allocation of resources [80].

However, tensions may arise between commercial interests and the long-term sustainability aims, which will influence the PPPs’ contributions in attaining economic, ecological, and social goals [84]. Frictions between short-term profits and public good goals can be substantial [85,86]. For the success factors of PPPs to improve the sustainability-related objectives, risk management is a crucial one [87,88,89]. To alleviate the risks of private sector involving in delivering public goods, it is suggested the market orientation be changed to viewing public goods as well as profitable items, and governments be aware of the companies with lobbying interests and practices against sustainability principles [90]. Considering the purpose of business plays a critical role in enabling and accelerating actions to address socio-ecological challenges, enactive cognition or active inference should be applied [91]. Private sector actors could integrate creating social and environmental values into their business strategies rather than a singular focus on profits perceiving sustainability as a side concern [92]. The public sector could improve PPP performance through direct involvement (e.g., administration, conflict resolution, risk control), indirect guidance (e.g., institutional and relational support), and supervision [93]. Although the governance of SDGs is more state-led, to bring about wider systemic change, governments should empower private sector actors as well as civil society, and mediate the multi-stakeholder processes towards shared understanding and effective cooperation [90].

6. Conclusions and Discussion

The scientometric analysis presented in this paper quantifies the scientific output of the risk governance and sustainability research, showing its interdisciplinary feature but environment-oriented. The journal “Sustainability” was found to be the most productive journal in this field. This paper visualizes author contribution spread in countries/regions, in institutions, and their collaboration networks. The US and UK are the leading countries in the research network, followed by Australia, the Netherlands, and Germany. Unlike the US, the UK has stronger links with other European countries. Five main research themes emerged from the articles, which are “Resilience and adaptation to climate change”, “Urban risk governance and sustainability”, “Environmental governance and transformation”, “Collaborative governance and policy integration”, and “Corporate governance and sustainability”. The interconnectedness of these clusters will be explained here.

The concepts of risk governance and sustainability have received increasing global attention of scholars from diverse disciplines, including engineering, natural sciences, and social sciences. At first, the two research fields develop separately, until the first paper of the intersection field appeared at a conference in 1998, discussing the agriculture experience generalization from Asia to Africa. In the 1990s, the side effects of urbanization and industrialization on the environment became much clearer and the interconnected social-ecological systems pose challenges to the rigid administration system. Environmental management in an engineering and technical way to clean up pollutants is far from enough. Sustainability policy goes beyond environmental policy, and even cosmopolitan policy making on sustainable development is called for. What does the future hold? We will still face uncertain extreme events, climate change, and different kinds of risks (e.g., terrorism, pandemic, industry accidents) may interact, with the impacts then mediated by location, scale, density and lead to possible cascading outcomes. The human system, the urban system, and the environment system are all parts of the whole ecosystem. Any of the multiple risks it faces, its reactions can also exert impacts back to the system. The feedback loops across sectoral, temporal, and across boundaries from local to international, might amplify or reduce certain risks. Thus, risk governance integrating diverse knowledge from stakeholders is crucial to effectively tackle the uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, especially when conflicts could be worsened as multi-actors have different values and interests, and have different preferences and evaluations about objectives and response-options. In this way, risk governance can be a process of participation and coordination, and a means of coping with the uncertainty and complexity to achieve sustainable outcomes. Technology innovation, institutional reforms, and effective policy implementation are often discussed in the trajectories of transformative change. Even if they become indispensable components of the transformative governance towards sustainability, the problem that co-evolution of multiple systems, such as the socio-technical transition, still exists. Mutual learning and knowledge sharing across disciplines and across communities could be a good start to adapt. Learning by doing does need experimentation of practices, such as corporate social responsibility. In this way, risk governance, able to improve the adaptive capacity, can be a useful way to sustainability at large, and a constant aim to be optimized in the process of sustainable development.

The linkage between risk governance and sustainability deserves more attention, especially when confronting the interconnected global challenges. The paper visualized the latent semantic structure in the line of risk governance and sustainability research, which is not noticeable due to the fragmentedly specialized literatures. In this way, risk governance and sustainability could be entry points to that research in the five identified themes. The theoretical progress in risk governance and sustainability will forward the problem-solving of the five themes. Empirical studies should be strengthened to verify efficacy of theories. And, the other way round, the different application fields can enrich theory-driven evaluations by using case studies, modeling, and other methods from various disciplines. It enables exchange of experiences and expertise in a larger scope. Innovative solutions to sustainability and risk mitigation can be more easily initiated from such a systematic perspective.

For example, when private sector actors incorporate sustainability issues into their governance models, it could provide management with emerging risk areas and opportunities presented by risks, which could be overlooked. Corporate social responsibility in variate contexts can lead to joint partnerships for the SDGs in an international and multi-sector way if implementation determinants and complexities arising from geographical and cultural differences are addressed with more care. The prominence of climate change discussions calls for more proactive actions from companies. How far it goes is largely dependent on policy integration, which aligns the interdependency between norms of sustainable development and implementation in sector-specific contexts, and its research work is in its infancy. Furthermore, trajectories of transformative change demand more co-evolutionary interactions between multiple systems and collaboration of different stakeholders. The re-invented industrial metabolism will be a continuous co-generation process by systems scholars, transition scholars, development scholars, politicians, business executives, other scientists and practitioners, and the civil society. The risk research community could play a more important role than ever, both in theory and in practice. In particular, the risk governance framework can provide a bridge for mutual learning and understanding across disciplines and boundaries towards sustainability-related objectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and J.L.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, H.L. and J.L.; formal analysis, H.L. and J.L.; resources, H.L. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; visualization, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund for Young Scholars (grant number 18CZZ010); the Integrity Research Program at Jilin University (grant number 2017LZY016); and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 51874042 and 51904185).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees for their insightful and detailed comments to improve the quality and presentation of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. Protecting and Mobilizing Youth in COVID-19 Responses. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2020/05/PB_67.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Lee, D.; Kang, J.; Kim, K. Global Collaboration Research Strategies for Sustainability in the Post COVID-19 Era: Analyzing Virology-Related National-Funded Projects. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Esfandabadi, Z.S.; Zanetti, M.; Scagnelli, S.; Siebers, P.-O.; Aghbashlo, M.; Peng, W.; Quatraro, F.; Tabatabaei, M. Three Pillars of Sustainability in the Wake of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda for Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.; Brandli, L.; Salvia, A.; Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Platje, J. COVID-19 and the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Threat to Solidarity or an Opportunity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Florin, M.-V.; Renn, O. COVID-19 Risk Governance: Drivers, Responses and Lessons to be Learned. J. Risk Res. 2020, 23, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawumi, T.O.; Chan, D.W.M. A Scientometric Review of Global Research on Sustainability and Sustainable Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billi, M.; Mascareño, A.; Edwards, J. Governing Sustainability or Sustainable Governance? Semantic Constellations on the Sustainability-Governance Intersection in Academic Literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Gálvez-Sánchez, F.J.; López-Martínez, G.; Molina-Moreno, V. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability. A Bibliometric Analysis of Their Interrelations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M. Sustainability and Wellbeing: A Scientometric and Bibliometric Review of the Literature. J. Econ. Surv. 2016, 31, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerlandt, F.; Li, J.; Reniers, G. The Landscape of Risk Communication Research: A Scientometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Goerlandt, F.; Reniers, G. An Overview of Scientometric Mapping For the Safety Science Community: Methods, tools, and framework. Saf. Sci. 2021, 134, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berger, A. Is Agricultural Research in Africa Worthwhile Today? In Twice Humanity—Implications for Local and Global Resource Use; Stockholm: The Nordic African Institute and Forum for Development Studies Uppsala; Nordiska Afrikainstitutet: Uppsala, Sweden, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Munaretto, S.; Siciliano, G.; Turvani, M. Integrating Adaptive Governance and Participatory Multicriteria Methods: A Framework For Climate Adaptation Governance. Ecology Society 2014, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive Governance of Social-Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 15, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renn, O. Risk Governance: Coping with Uncertainty in a Complex World; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, S.; Dai, E.; Liu, D.; Yin, Y. Identification and Categorization of Climate Change Risks. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2008, 18, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, N.; Mach, K.; Constable, A.; Hess, J.; Hogarth, R.; Howden, M.; Lawrence, J.; Lempert, R.; Muccione, V.; Mackey, B.; et al. A Framework For Complex Climate Change Risk Assessment. One Earth 2021, 4, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRGC (International Risk Governance Council). Introduction to the IRGC Risk Governance Framework. Revised Version; EPFL International Risk Governance Center: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M. Collaboration, Adaptation, and Scaling: Perspectives on Environmental Governance for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hurlbert, M.; Gupta, J. Adaptive Governance, Uncertainty, and Risk: Policy Framing and Responses to Climate Change, Drought, and Flood. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnheim, B.; Tezcan, M.Y. Complex Governance to Cope with Global Environmental Risk: An Assessment of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2010, 16, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, G.D.R.; Fernández, M.C.G.; Colsa, Á.U. Unleashing the Convergence amid Digitalization and Sustainability towards Pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Holistic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 122204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, P.; Hegger, D.; Bakker, M.; Rijswick, H.V.; Kundzewicz, Z. Toward More Resilient Flood Risk Governance. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, J.G.; Newell, B.; Proust, K.; Capon, A. Urbanization, Extreme Events, and Health: The Case for Systems Approaches in Mitigation, Management, and Response. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2016, 28, 15S–27S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Klinke, A. A Framework of Adaptive Risk Governance for Urban Planning. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2036–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urbinatti, A.M.; Benites-Lazaro, L.L.; Carvalho, C.M.; Giatti, L. The Conceptual Basis of Water-energy-food Nexus Governance: Systematic Literature Review Using Network and Discourse Analysis. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2020, 17, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renn, O.; Klinke, A.; Schweizer, P. Risk Governance: Application to Urban Challenges. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renou, Y.; Bolognesi, T. Governing Urban Water Services in Europe: Towards Sustainable Synchronous Regimes. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X. River Chief System as a Collaborative Water Governance Approach in China. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2020, 36, 610–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O.; Schweizer, P. Inclusive Risk Governance: Concepts and Application to Environmental Policy Making. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H.; Biermann, F. Sustainability: Politics and Governance. In Sustainability Science: An Introduction; Heinrichs, H., Martens, P., Michelsen, G., Wiek, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F. Earth System Governance: World Politics in the Anthropocene; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Betsill, M.M.; Gupta, J.; Kani, N.; Lebel, L.; Liverman, D.; Schroeder, H.; Siebenhüner, B. Earth System Governance: People, Places, and the Planet: Science and Implementation Plan of the Earth System Governance Project; IHDP: Bonn, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Fairbrass, J.; Jordan, A.; Paavola, J.; Rosendo, S.; Seyfang, G. Governance for Sustainability: Towards a ‘Thick’ Analysis of Environmental Decisionmaking. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2003, 35, 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejová, M.; Briggs, C.M. Embracing the Darkness: Methods for Tackling Uncertainty and Complexity in Environmental Disaster Risks. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2021, 21, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, S.; Dunphy, D.; Martin, A. Governance of Environmental Risk: New Approaches to Managing Stakeholder Involvement. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. Potsdam Memorandum. 2007. Available online: https://sarpn.org/documents/d0002870/Potsdam_Memorandum_Oct2007.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Brien, O.K. Global Environmental Change II. Prog. Human Geogr. 2012, 36, 667–676. [Google Scholar]

- Feola, G. Societal Transformation in Response to Global Environmental Change: A Review of Emerging Concepts. Ambio 2014, 44, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Revi, A.; Satterthwaite, D.; Aragon-Durand, F.; Corfee-Morlot, J.; Kiunsi, R.; Pelling, M.; Roberts, D.; Solecki, W.; Gajjar, S.P.; Sverdlik, A. Towards Transformative Adaptation in Cities: The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment. Environ. Urban. 2014, 26, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; Hel, S.V.D.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Hurlbert, M.; Anderton, K.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A.S. Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations towards Sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergh, J.; Truffer, B.; Kallis, G. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions: Introduction and Overview. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Governance for Sustainability. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2007, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, A.A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar]

- Wyborn, C. Cross Scale Linkages in Connectivity Conservation: Adaptive Governance Challenges in Spatially Distributed Networks. Environ. Policy Gov. 2015, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulibarri, N.; Emerson, K.; Imperial, M.T.; Jager, N.W.; Newig, J.; Weber, E. How does Collaborative Governance Evolve? Insights from a Medium-n Case Comparison. Policy Soc. 2020, 39, 617–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondízio, E.S.; Brien, K.; Bai, X.; Biermann, F.; Steffen, W.; Berkhout, F.; Cudennec, C.; Lemos, M.C.; Wolfe, A.P.; Palma-Oliveira, J.; et al. Re-conceptualizing the Anthropocene: A Call for Collaboration. Glob. Environ. Chang. Part A Hum. Policy Dimens. 2016, 39, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. Perspectives on Policy Integration. Environ. Politics 2006, 15, 666–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, W.; Hovden, E. Environmental Policy Integration: Towards an Analytical Framework. Environ. Politics 2003, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Underdal, A. Integrated Marine Policy: What? Why? How? Mar. Policy 1980, 4, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K.; Kleinschmit, D.; Rayner, J. Achieving Policy Integration across Fragmented Policy Domains: Forests, Agriculture, Climate and Energy. Environ. C Gov. Policy 2016, 34, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C. Sustainable Financial Risk Modelling Fitting the SDGs: Some Reflections. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, N.; Azcárate-Llanes, F.; Sierra-García, L.; García-Benau, M.A. Financial Institutions’ Risk Profile and Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Corporate Governance and the Financial Crisis—Conclusions and Emerging Good Practices to Enhance Implementation of the Principles; OECD: Paris, France, 2010; Available online: www.oecd.org/daf/ca/corporategovernanceprinciples/44679170.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Rehman, H.; Ramzan, M.; Haq, M.; Hwang, J.; Kim, K.-B. Risk Management in Corporate Governance Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.-J.; Chen, Y.-C. Is a Firm’s Financial Risk Associated with Corporate Social Responsibility? Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 2175–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, S.; Cellier, A.; Manita, R.; Saeed, A. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Reduce Financial Distress Risk. Econ. Model. 2020, 91, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, L.; Chen, W.; Lin, J.-R. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility Performance on Financial Risk. NTU Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 257–310. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities. Implementing the Partnership for Growth and Jobs: Making Europe a Pole of Excellence on Corporate Social Responsibility; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, C.; Oikonomou, I. The Effects of Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosures and Performance on Firm Value: A Review of the Literature in Accounting and Finance. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M.P.; Fernando, C.S. Environmental Risk Management and the Cost of Capital. Strat. Mgmt. J. 2008, 29, 569–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Salama, A. Does Community and Environmental Responsibility Affect Firm Risk? Evidence from UK Panel Data 1994–2006. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2011, 20, 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, P.; Sandwidi, B. CSR Engagement and Financial Risk: A Virtuous Circle? International Evidence. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, M.A.; Steensma, H. Disentangling the Theories of Firm Boundaries: A Path Model and Empirical Test. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, C.; Sierra, V. Sustainable Supply Chains: Governance Mechanisms to Greening Suppliers. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoît-Norris, C.; Cavan, D.A.; Norris, G. Identifying Social Impacts in Product Supply Chains:Overview and Application of the Social Hotspot Database. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1946–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tseng, M.; Tan, P.A.; Jeng, S.-Y.; Lin, C.; Negash, Y.T.; Darsono, S. Sustainable Investment: Interrelated among Corporate Governance, Economic Performance and Market Risks Using Investor Preference Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phan, H.V.; Nguyen, N.; Nguyen, H.T.; Hegde, S. Policy Uncertainty and Firm Cash Holdings. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, N.; Mansi, S.; Saffar, W. Political Institutions, Connectedness, and Corporate Risk-taking. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2013, 44, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Critical Factors to Achieve Sustainability of Public-Private Partnership Projects in the Water Sector: A Stakeholder-Oriented Network Perspective. Complexity 2020, 2020, 8895980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Governance and Sustainability: An Investigation into the Relationship between Corporate Governance and Corporate Sustainability. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Vitaliano, D.F. An Empirical Analysis of the Strategic Use of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2007, 16, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rezaee, Z. Business Sustainability Research: A Theoretical and Integrated Perspective. J. Account. Lit. 2016, 36, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, J.F.; Busch, T.; Jancso, L.M. How Media Coverage of Corporate Social Irresponsibility Increases Financial Risk. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 2266–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Moussa, T. Do Board s Corporate Social Responsibility Strategy and Orientation Influence Environmental Sustainability Disclosure? UK Evidence. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 1061–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z.; Alipour, M.; Faraji, O.; Ghanbari, M.; Jamshidinavid, B. Environmental Disclosure Quality and Risk: The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2021, 12, 733–766. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.F.; Romi, A.M. Does the Voluntary Adoption of Corporate Governance Mechanisms Improve Environmental Risk Disclosures? Evidence from Greenhouse Gas Emission Accounting. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 637–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UN Forum Highlights ‘Fundamental’ Role of Private Sector in Advancing New Global Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2015/09/un-forum-highlights-fundamental-role-of-private-sector-in-advancing-new-global-goals/ (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Pinz, A.; Roudyani, N.; Thaler, J. Public–Private Partnerships as Instruments to Achieve Sustainability-related Objectives: The State of the Art and a Research Agenda. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wörsdörfer, M. Equator Principles: Bridging the Gap between Economics and Ethics? Bus. Soc. Rev. 2015, 120, 205–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Villar, R.G. Identifying Determinants of CSR Implementation on SDG 17 Partnerships for the Goals. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1847989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.C.; Marques, R.C.; Cruz, C.O. Public–Private Partnerships for Wind Power Generation: The Portuguese Case. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenjan, J.F.M.; Enserink, B. Public–Private Partnerships in Urban Infrastructures: Reconciling Private Sector Participation and Sustainability. Public Adm. Rev. 2009, 69, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberherr, E.; Klinke, A.; Finger, M. Towards Legitimate Water Governance? Public Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 923–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keers, B.B.M.; van Fenema, P.C. Managing Risks in Public-Private Partnership Formation Projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.; Ok Choi, S. Success Factors: Public Works and Public-Private Partnerships. Int. J. Public Sector Manag. 2008, 21, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameyaw, E.E.; Chan, A.P.C. Risk Allocation in Public-Private Partnership Water Supply Projects in Ghana. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.A.; Garvin, M.J.; Gonzalez, E.E. Risk Allocation in U.S. Public-Private Partnership Highway Project Contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphof, R.; Melissen, J. SDGs, Foreign Ministries and the Art of Partnering with the Private Sector. Glob. Policy 2018, 9, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boik, J.C. Science-Driven Societal Transformation, Part I: Worldview. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, F.; Stubbs, W.; Raven, R.; Porto de Albuquerque, J. The ‘Purpose Ecosystem’: Emerging Private Sector Actors in Earth System Governance. Earth Syst. Gov. 2020, 4, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zeng, S.; Lin, H.; Zeng, R. Impact of Public Sector on Sustainability of Public-Private Partnership Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).