Abstract

This article theorizes how a social enterprise builds, strengthens, and legitimizes community among marginalized people. Prior work investigated social enterprises and community-led social enterprises, or social enterprises rooted in community culture. Missing are perspectives on the roles of social enterprises in community creation and support among marginalized individuals. This qualitative interpretive study draws on ethnographic and netnographic data collection of the social enterprise Familyship; marginalized entrepreneurs developed a social enterprise to address a particular social problem, thus helping other marginalized people to address their constraints and collectively legitimizing a new meaning of what family is and does as a community. The study finds five overarching themes—namely, informing, protecting, connecting, supporting, and normalizing—that characterize Familyship’s process of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals. I discuss these findings with regard to contributions to theory on social enterprise and institutional voids, as well as social enterprise and online communities.

1. Introduction

Markets and governmental institutions often fail to serve people that live outside the mainstream, leaving institutional voids to be filled, or not, by other means, such as social enterprises [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Social enterprises are the institutionalized outcome of “the process of creating and growing a venture, either for-profit or non-profit, where the motivation of the entrepreneur is to address social challenges” [7] (p. 53). Social enterprise is a fascinating phenomenon because it involves many facets: entrepreneurial innovation, organizational structures and legitimation, and innovative ways of using business and market logics to create solutions to the burning social problems of our times.

One such problem is the marginalization of certain persons or groups within society. Prior research has shown that many consumers feel marginalized or stigmatized by current social and market structures, such as gender and sexuality [8,9], ethnicity [10,11,12], race [13,14], physical ideals [15], or religion [16]. Another case that I identify is the dominant meaning of family within society and the process of family formation, which is the context of this study.

Many social enterprises exist to serve marginalized individuals [2,4,17,18,19,20]. Examples include people in poverty (e.g., FINCA), women entrepreneurs (e.g., microfinance), physically and socially disadvantaged people (e.g., WISEs—work-integration social enterprises), etc.

Few studies have examined the roles of social enterprise in community creation and support among marginalized individuals. There is considerable research addressing social enterprises and community [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]; however, it focuses mainly on community-led social enterprises or social enterprises rooted in community culture. Conspicuously missing are perspectives on the roles of social enterprise in community creation and support among marginalized individuals.

In one notable exception, Teasdale [17] conducted an in-depth case study to investigate the potential for social enterprise to combat disadvantage/social exclusion in an inner-city community. The author found that social enterprises can provide employment within an area, can provide a space for excluded individuals to bond together, may deliver services to excluded groups, and can aid social inclusion at a societal level. While the findings suggest that social enterprises have the ability to bring individuals together and decrease social exclusion, they do not reveal the specific ways in which social enterprises bond marginalized people together in building, strengthening, and legitimizing community.

Jurado [18] argues for establishing a For-Profit Social Enterprise Sector in order to directly alleviate the lack of social mobility in marginalized communities. He proposes For-Profit Social Enterprises as a tool to tackle unequal income distribution “by targeting communities that have proven to be disproportionately susceptible to current income inequality trends” (p. 371). The paper presents three social mobility approaches through social enterprises—namely, improving marginalized neighborhoods, providing access to additional resources, and facilitating direct economic empowerment. The paper focuses on regulatory issues associated with the For-Profit Social Enterprise Sector, but it does not reveal how marginalized communities are empowered through social enterprises.

Finlayson and Roy [27] studied a project based in Scotland that was “designed to stimulate the creation of social enterprises involved in community growing” (p. 76). As social enterprise activity in communities is increasingly imposed by regulatory bodies following the goal to empower social and economic development interventions, the authors investigated the actors involved in community social enterprise development and the degree of empowerment for their communities. They find that “social enterprise originating outside communities and facilitated by external actors is potentially disempowering, particularly when social enterprise development does not necessarily align with community needs” (p. 76). They argued that it is therefore important to involve community participation at early project stages. This study deals with the strengthening of an existing geographic community and, therefore, does not reveal how community may be fostered among and for the benefit of marginalized people.

Parthiban et al. [2] carried out an in-depth qualitative field inquiry into the case of GenLink5, a small social entrepreneurial venture in India helping marginalized communities. The social enterprise “addresses the problem of poor quality of rural education (rural education void) and the problem of social isolation of the urban elderly (productive aging void)” (p. 634). The authors introduced the notion of complementary institutional voids—complementary meaning that each void is filled with the help of the other. A central role within the social enterprise is played by an ICT platform “empowering marginalized communities by expanding their agency and by serving as an important enabler of opportunities” (p. 635) and “bridging the two marginalized communities, namely the elderly and the rural children” (p. 639). The authors’ ideas of filling institutional voids, empowering marginalized communities, and matching people through an ICT platform will be echoed in my own study; however, their findings fall short of answering my research question: How can a social enterprise build, strengthen, and legitimize community among marginalized people?

2. Familyship: A Social Enterprise Story

I address the research question from the well of data that I have constructed through 1.5 years of ethnographic involvement with a social enterprise called Familyship. In the German-speaking parts of Europe, laws reflect a narrow societal understanding of family and deny institutional support for people with alternative visions of their desired family constellations. My research illustrates how a pair of marginalized German consumers created a novel digital platform solution to overcome constraining social and legal barriers to family formation. Through Familyship, marginalized consumers use an online platform to organize families for the purpose of conceiving, bearing, and raising children.

Familyship was founded by a lesbian couple, Christine and Miriam, as a way of countering exclusionary market and regulatory structures. They wanted to realize their non-traditional vision of a family, consisting of two mothers and a father, ideally a gay man who would provide sperm and also take an active role in childrearing. They faced serious legal and social barriers to their desires, as the regulations for family creation in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland are very conservative. For example, only two people can be the legal parents of a child, fertility clinics are not allowed to treat homosexual couples and single women, homosexual couples need to be legally married, and one must endure a long and difficult process of second-parent adoption to become the legal guardian for their partner’s child.

As a lesbian couple desiring a non-traditional family, Christine and Miriam fell into an institutional void. Neither government services nor the market offered them a solution. They decided to assemble a solution on their own using the resources available to them. With technical knowhow—Miriam is an IT developer—they created a web page for the purpose of recruiting and screening potential fathers.

Christine and Miriam’s website was successful. They received and screened numerous inquiries and eventually found the ideal potential father for their future child. Upon achieving that goal, they intended to close down the platform. The responses to their site were so numerous and robust, however, that they realized their personal problem was shared widely by others who were similarly marginalized by social and legal systems in German-speaking Europe. Driven by a philanthropic wish to help other individuals form families and raise children, they decided to expand their website into a digital platform rather than shut it down. The founders’ embodied understanding of stigmatization, vulnerability, and barriers to family formation helped them create a social enterprise that meets the real needs of a marginalized group. This observation is in line with Finlayson and Roy [27] (p. 76), who found that social enterprises originating inside communities are empowering, as they align with community needs. Familyship addresses the needs of marginalized groups, such as LGBTQ+ members, single women, and others with a non-traditional understanding of family who are facing stigmatization in their family-creation process.

The mission of Familyship follows a liberal understanding of the meaning of family. The mission statement identifies the nature of the marginalization it attempts to address and makes clear its function as a facilitator of alternative family formation:

“Welcome to your path to your own family! You want to become a parent? Are you possibly single, gay or lesbian? Whether co-parenting, rainbow family, multi-parenting or single parenting: create the family that suits you! Here people are getting in touch with other people who are interested in founding a family via a non-traditional way. Familyship is the place where families are born! Familyship is all about one thing: your wish to create a family. On Familyship, people get to know each other and start a family on a friendly basis. Sexual orientation or marital status are of secondary importance. The platform provides information on alternative family models and is the largest active German-speaking community in co-parenting” (Familyship.org 2020).

The social enterprise’s mission is to enable family creation for everyone, regardless of sexual orientation and relationship status. It does this by providing a digital platform for connecting aspiring family creators with other people that have similar goals and complementary resources cf. [2] in order to assemble non-traditional families in ways not supported by existing social or governmental institutions.

2.1. The Community

A central element of the social enterprise Familyship is its community. First, the founders built a community for the users of the Familyship platform. The community on the Familyship platform is restricted to its official users who pay the user fee. The purpose of that community is to connect people to create families in a safe space. Second, the founders created a Facebook community to connect to a broader community of interest with the main purpose of informing, educating, provoking discussion, and normalizing the topic within a more public audience. The Facebook community is open for anyone who is interested in alternative, non-traditional family constellations. This is an excerpt from Christine’s (founder) personal story on the website:

“I would like to share articles, documentaries, criticism, suggestions, observations, notes and whatever else might be of interest. On the subject of family. On the subject of co-parenting. On the subject of family beyond mother-father-child with wedding ring. I try to spread it through the social networks of our community.”

2.2. Business Model

Although driven by a social mission, the digital platform incurs expenses—e.g., server time, IT development, and advertising—that need to be covered. To offset the expenses, the founders instituted a user fee: 29 euros for one month, 49 euros for six months, or 60 euros for unlimited access (Familyship.org 2020), with the main purpose of protecting the community and maintaining the online service.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

This study draws on ethnographic and netnographic data. Data collection started in 2018 with semi-structured interviews of the social entrepreneurs according to McCracken [33]. Investigating the founding story of the social enterprise was essential for understanding the meaning of the digital platform for its community. The interview lasted 1.5 recorded hours, resulting in 32 transcribed single-spaced pages. The founders granted access to the Familyship community and Familyship platform and helped me to recruit for in-depth interviews with community members. I conducted longitudinal in-depth interviews with 23 families over a period of 1.5 years, resulting in 37.65 recorded hours and 602.5 transcribed single-spaced pages. The insider perspective of community members is relevant to understanding the needs of platform users and their interactions with other community members. I triangulated the interview data with netnographic data collection on the Familyship platform and the Familyship Facebook Group according to Kozinets [34,35]. I was especially interested in the platform’s structure, services, rules, and functions, as well as in users’ experiences when navigating the platform. I focused on narratives, communal exchanges, online rules and practices, rituals, discourses, and innovative forms of collaboration and organization cf. [35] (p. 1). Additionally, I examined media coverage (46 articles, documentaries, podcasts, videos, and blogposts) to understand the societal and legal discourses around the social enterprise.

3.2. Data Analysis

The data analysis followed an inductive approach [36] through several stages. First, I applied open and axial coding, starting with “an analysis using informant-centric terms and codes” [37] (p. 18), followed by an analysis using “researcher-centric concepts, themes, and dimensions; for the inspiration for the 1st- and 2nd-order labeling” [37] (p. 18). I analyzed the data both horizontally (across the families) and vertically (within families) [38]. As the analysis progressed, overarching themes, as well as similarities and differences among categories, emerged. In qualitative research, it is common to move iteratively [39] between data and theoretical understandings [40] (Belk et al., 2012) “to see whether what we are finding has precedents, but also whether we have discovered new concepts” [37] (p. 21). As a result of the data-theory iterations, I developed “2nd-order aggregate dimensions” [37] (p. 20). The data analysis revealed several important research directions, and this paper reports the findings related to community building and support among marginalized individuals.

4. Findings—The Social Enterprise Community for Marginalized Individuals

Five overarching themes characterize Familyship’s function of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals: Table 1 summarizes the findings along five dimensions: informing, protecting, connecting, supporting, and normalizing.

Table 1.

Overview of community themes.

4.1. Informing

Informing refers to communicating knowledge about co-parenting, alternative family constellations, and legal and societal developments to interested parties and the general public. The digital platform informs through media activities, their Facebook community, and the founders’ blog.

The main information tools in the case of Familyship.org are media activities. The founders regularly give interviews for newspapers, TV documentaries, or podcasts. Moreover, they publish press releases relating to alternative family constellations, including topics such as the history and future of the family, rainbow families, legal developments in different countries, co-parenting portraits, and others. A section on their platform called ‘Familyship in the press’ lists all media activities that relate to co-parenting (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Media activities.

The second main information tool is the Familyship Facebook Community (Figure 2). The Facebook Community is directed to a much broader audience than only the members of the internal and protected Familyship platform. The Familyship Facebook site shares articles and news about non-traditional family constellations, new legislation connected to surrogacy, sperm donation, multiple parenthood, and other related topics.

Figure 2.

Familyship Facebook Community.

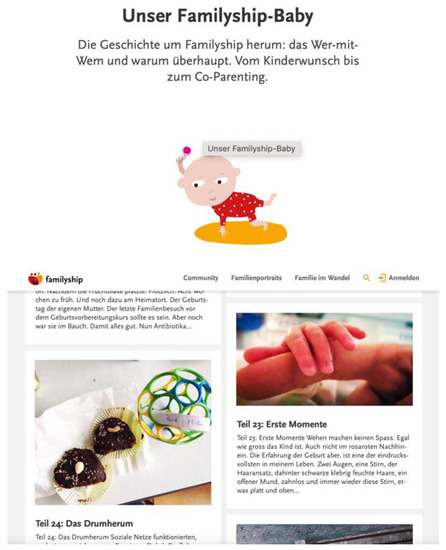

A third and very personal element of informing is the founders’ blog on the digital platform. The blog is written like a diary and documents the whole development—from creating the social enterprise, finding the co-father for their child, several tries to conceive the child, and life as a family. Figure 3 illustrates the introduction section “Our Familyship Baby. The story around Familyship: the who-with-who and why of it all. From the desire to have children to co-parenting” and an excerpt from the blog about the first moments as a family with the newborn.

Figure 3.

Founders’ blog.

Media activites, the Familyship Facebook community, and the founders’ blog serve as extended information tools. Infoming is a main dimension for Familyship’s function of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals for several reasons. Knowing that there are alternative ways of family creation, the social enterprise attracts those who might find the offering useful for their lives. At the same time, it filters those that do not fit with the idea of Familyship. In being informed about alternative ways of thinking and doing, information stimulates thought on non-traditional family creation and serves to frame problems regarding stigmatization and legal and societal barriers for marginalized people. Moreover, information provides resources to marginalized individuals, and it thus helps them to confirm/reject decisions for their lives. Learning about a variety of family constellations and getting informed about the processes of how co-parenting works helps individuals of the marginalized community to create the alternative family constellation they desire. As a community, informing each other and staying up to date on legal and societal advances is an important element in overcoming the barriers that the marginalized community has been facing.

4.2. Protecting

Protecting the emerging community is an important function, especially among marginalized or potentially stigmatized people. Familyship is prioritizing the protection of its community, as announced by the social enterprise:

“Familyship—the Community. The topic of desiring to have children is usually a sensitive one. Hardly anyone wants their neighbor to know more about it. This is why our co-parenting community is protected.”

Protection creates a private atmosphere within the Familyship community. The social enterprise reaches this privacy by limiting access to only those who are truly interested and willing to pay a user fee. Moreover, the social enterprise states:

“Data protection is very important to us. There are people who are concerned that they will be identified because their living or working environment is very conservative. We can perhaps comfort you a bit: Familyship is too expensive for people who ‘just want to have a look’ to see whether their neighbors are registered. So far, we are not aware of any case in which someone has registered on the site in order to ‘spy on’ others. Furthermore, it is of course up to you how much information you disclose about yourself. So it is possible to select a user name of your choice and an image that characterizes you in a different way, instead of providing a real portrait photo. And the profile text does not have to state your shoe size, hair color and education certificate or employer; you can certainly describe yourself in another way.”

Prioritizing data protection and pointing to solutions to protect one’s identity within the community help community members to feel comfortable and safe on the digital platform, especially as the topic of alternative family creation is a sensitive one. Familyship creates a safe space virtually and also sometimes geographically in face-to-face meetups (as the next section will highlight). Illustrating sensitivity to these topics by creating a space that is free of marginalization and stigmatization is of the highest relevance for the emerging community—much like starting plants in a greenhouse so they have a better chance to grow than they would in a hostile environment. As this section has illustrated, protecting is a main dimension for Familyship’s function of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals.

4.3. Connecting

Connecting refers to offering opportunities for like-minded people to get together, share their experiences, build relationships, and develop a feeling of togetherness. This section addresses how the social enterprise Familyship builds a community by connecting interested parties through its community and local meetups.

The protected Familyship user community is the central element of the digital platform. It allows Familyship users to have access to other like-minded people, which they describe as a strong relief from their marginalization:

“At some point I just started to google for an alternative solution and found a concept called co-parenting, and it made total sense to me. I continued to read and google, and I discovered Familyship. I couldn’t believe that after all this time of worrying and thinking, my solution was right there in front of me, online! I got registered for a small entry fee and from one moment to the next the burden fell away, and I felt so relieved to see a realistic option for having a child.” (Family #13)

Finding the protected Familyship community via the social enterprise is not like any other social platform for its users; it has a deeper meaning and might be life-changing for them. The community welcome statement on the protected platform (Figure 4) states:

Figure 4.

Familyship community.

“Familyship is a social community. Here people are getting in touch with other people who are interested in founding a family via a non-traditional way. Your journey can be about finding a co-parent, exchanging with like-minded people, men who want to become active fathers or women who want a sibling for their firstborn, sperm donors, rainbow families, singles or multi-parent families. Familyship is the place where families are born!”

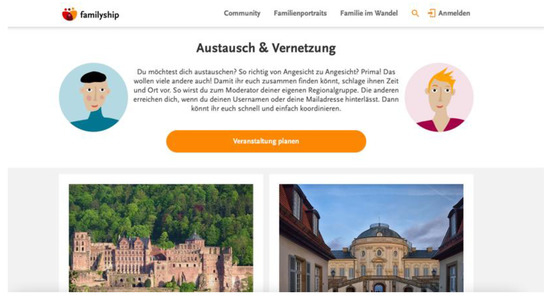

The protected Familyship community offers access to around 6500 active members who are interested in family creation. A further element for connecting with Familyship users is local meetups/local groups. The section on Familyship.org called ‘Exchange & Networking’ (Figure 5) states:

Figure 5.

Local groups/meetups.

“You want to exchange ideas? Really face to face? Great! Many others want that, too. So that you can get together, suggest a time and place. This is how you become the moderator of your own regional group. The others can reach you via your username or email address. This way you can coordinate conveniently.”

The ‘Exchange & Networking’ section also offers access to local groups that have already been established. For example, a local group called “gay-daddy meetup for rainbow fathers in co-parenting constellations” can be found in Berlin. As this section has illustrated, connecting is a main dimension of Familyship’s function of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals. Offering different ways for its community members to get to know each other via online or offline channels is the first step to establishing a long-lasting community. Establishing and experiencing a feeling of belonging [41,42]—online or offline—is important for supporting others within a marginalized community.

4.4. Supporting

Supporting means to provide assistance to clarify issues around alternative family constellations. The digital platform is doing so by offering opportunities for Familyship community members to reach out to one another for any questions regarding alternative family constellations. Additionally, the social enterprise established a ‘Q&A and Glossary’ section around alternative family creation (Figure 6). Moreover, Familyship is advocating for and promoting the interests of non-traditional families through partnerships with support centers (Figure 7). One example of using the digital platform to reach out to other Familyship community members is the quote below:

Figure 6.

Q&A and Glossary.

Figure 7.

Support centers.

“I am in a real dilemma. On the one hand, I live in a relationship. We have a child together with whom we have a great connection. On the other hand, I have long wanted nothing more than a second child. My partner definitely doesn’t want this and that is where the problem starts. I don’t see this unanswered question as a simple yes/no decision that will be finalized by any specific deadline. For me it is a process and so I am initially only looking for people for a positive, mutual exchange. Certainly there are many here on this platform whose family planning has not always been straightforward either. Or who are currently struggling with the arguments for and against.” (Male community member, Mid 40, academic)

Community members can be contacted via direct messages or via forums on the protected Familyship platform. Users can indicate their interest in being in exchange with others upon registration, and search filters will show all interested users.

The ‘Q&A and Glossary’ section helps to clarify the terminology and questions around alternative family creation. Terms such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and yes-sperm-donor are explained to clarify the topics around the creation of non-traditional families.

Moreover, a Q&A section elaborates on the most frequently asked questions, such as

“Is Familyship the right place for me? Where can I find legal advice?”.

Familyship has established official partnerships with local organizations for its community. The local support centers are present in several larger cities, and the experts provide direct offline guidance for non-traditional family constellations.

The three elaborated offerings of the social enterprise—opportunities for reaching out to other community members, Q&A and Glossary, and established partnerships with support centers—as elements that support the marginalized Familyship community. Supporting is a main dimension for Familyship’s function of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals. The support elements not only serve individual people in reaching their desire to become a parent, but also help the broader community to get direct help from like-minded people, learn from the experiences of others, establish a better understanding of alternative families, and connect with established partners.

4.5. Normalizing

Normalizing refers to establishing and legitimizing a more diverse understanding of what family means within society. Through family portraits, bedtime stories, and supporting words from proponents from various societal functions, Familyship takes steps towards legitimizing a broader diversity of family constellations. The section on family portraits illustrates several families that have been founded through the platform (Figure 8). Pictures, video documentations, and personal words from several co-parents convey a lively visualization of how family can be lived.

Figure 8.

Family portraits.

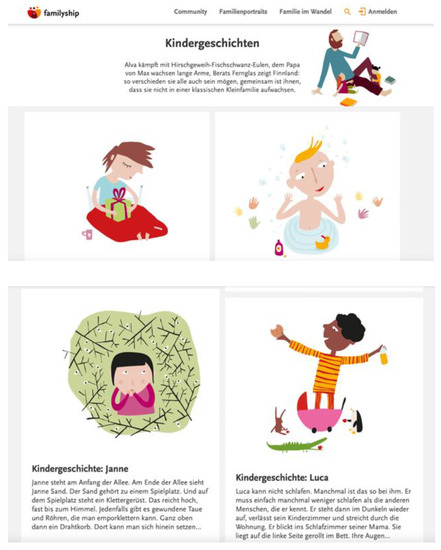

Another element on the platform that normalizes alternative families is the section ‘Bedtime stories’ (Figure 9). The stories are an offering to any parents that would like to tell a bedtime story that does not take the classical nuclear family for granted and makes non-traditional family constellations the center of these stories.

Figure 9.

Bedtime stories.

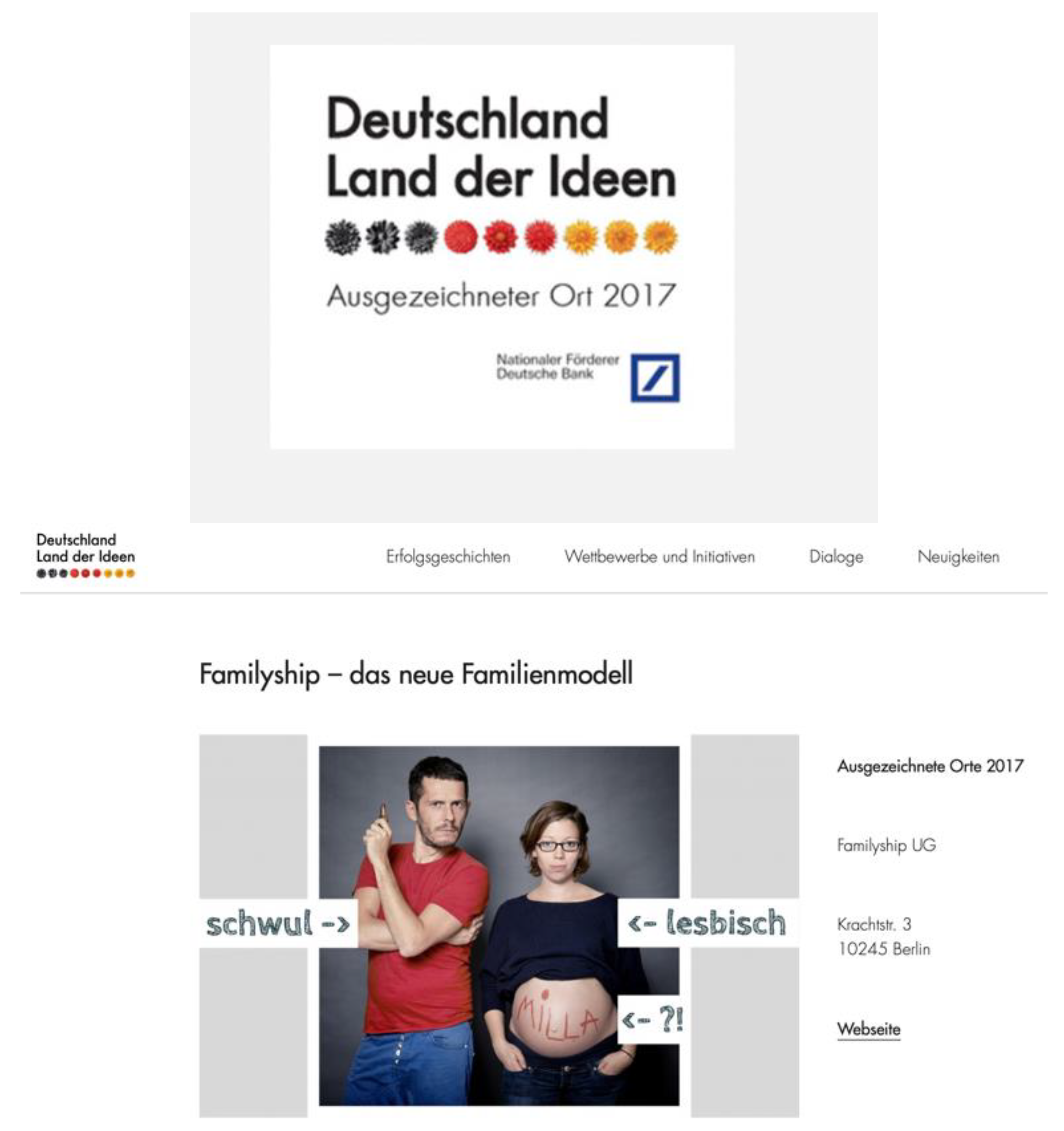

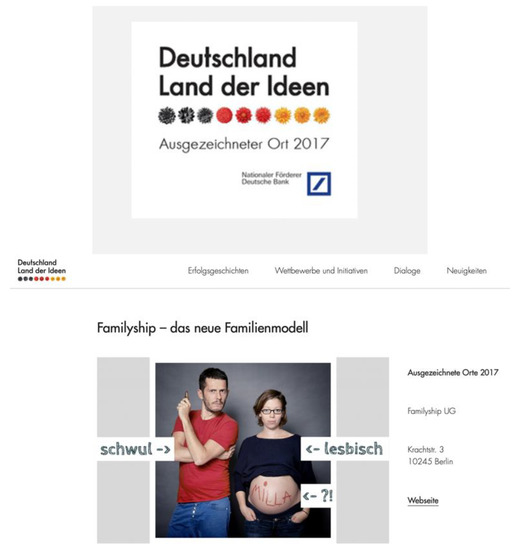

Familyship participates in award competitions, such as ‘Germany—the country of ideas’. The Familyship initiative was awarded for being an innovative place in 2017 (Figure 10). Receiving the recognition from such a well-established award competition signifies that a more diverse understanding of family is becoming more accepted within society.

Figure 10.

Award competition.

Proponents from various societal functions, such as lawyers, sociologists, psychologists, politics, filmmakers, etc., have shared their opinions (Figure 11) around the development of family and answered questions such as: What does science know about these developments? What impact does this have on legal issues? Are there moral boundaries around these family constellations? These findings resonated with Tracey et al. [43], who found that innovators achieve legitimacy by connecting with a macro-level discourse and aligning with highly legitimate actors. Connecting with a macro-level discourse means to “communicate views and participate in … societal discourse” [43] (p. 73) Aligning with highly legitimate actors means to “connect with a range of high-profile actors from multiple fields, thereby augmenting the legitimacy of their activities” [43] (p. 74).

Figure 11.

Proponents from various societal functions.

Family portraits, bedtime stories, and supporting words from proponents from various societal functions serve as steps toward normalizing a broader diversity of family constellations. Normalizing is a main dimension for Familyship’s function of building, supporting, and legitimizing a community among marginalized individuals. By illustrating the diversity of what family can be through family portraits, by establishing a different perspective of how family can be lived in bedtime stories, and by receiving support from legitimized societal actors, the social enterprise advocates for a greater acceptance of new family models. To summarize, the study’s findings have illuminated our understanding of how the social enterprise Familyship builds, strengthens, and leverages a marginalized community. Engaging in activities such as informing, protecting, connecting, protecting, supporting, and normalizing, the social enterprise essentially addresses alternative family creation at a collective level. We also noted several developments as a result of these activities. For example, the media increasingly reports about Familyship and a broader diversity of lived family constellations. Moreover, legislation is advancing in the direction of non-traditional families as well. We now conclude with a discussion of these findings.

5. Discussion

Drawing from my study on Familyship, I present a case of a social enterprise serving marginalized individuals and offer a new theoretical perspective on the role of social enterprise in community creation and support among marginalized individuals. The social enterprise takes on the responsibility of helping a marginalized group, as legal and social barriers impede family creation for some societal groups, such as single women, the LGBTQ+ community, and those with a non-traditional vision of family. This case is illustrative for a social enterprise filling institutional voids, as markets and governmental institutions fail to serve people that live outside the mainstream [1,2,3,4,5,6]. “Institutional voids arise at the complex intersection of existing institutions (or lack of it) and often require very structured interventions that depend on the institutional environment and the nature of the void [2] (p. 634).” The founders of Familyship had to face legal and societal barriers to family formation themselves and built a solution based on a digital platform. Familyship offers a solution for family creation and childrearing to a marginalized community that has been excluded from legislation. By informing, protecting, connecting, supporting, and normalizing, the social enterprise builds, strengthens, and legitimizes its community. The social enterprise Familyship fills a gap not met by the market or any governmental institution.

A central element in addressing the institutional void is the digital platform, which allows for connecting the marginalized community and serving it better. Prior work in consumer and marketing research has acknowledged the existence, power, and importance of online communities [44,45,46,47]. However, we did not find studies on the importance of online communities in relation to social enterprise. The social enterprise literature on communities has mainly focused on geographic communities [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], and not on online communities. An exception is Parthiban et al.’s (2020) study, which acknowledges the importance of “ICT centered institutional work to address institutional voids in the context of marginalized communities” [2] (p. 638). However, they did not present details on how institutional work done by a digital social enterprise serves marginalized communities. My study contributes a perspective on the specific functions of a digital social enterprise in building, strengthening, and legitimizing its community.

Drawing from the study’s findings, the digital platform connects people and nurtures a community, rather than building on a pre-existing community. Recent scholarship has mainly focused on community-led social enterprises or social enterprises rooted in community culture [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. In contrast to these perspectives, this research shows how a social enterprise can foster a strong community and contributes to our understanding of the roles of social enterprise in community creation and support among marginalized individuals. The Familyship community resonates well within the LGBTQ+ community/movement, as it was initially founded by a lesbian couple and addresses many issues that LGBTQ+ members are facing with regard to family creation. By connecting with the existing LGBTQ+ community/movement and LGBTQ+ families, the social enterprise creates additional synergies to address and alleviate stigma.

Funding

This research was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant number P1SGP1_188106.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of St.Gallen (protocol code HSG-EC-2018-09-13-A; 31st of May 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy of the study’s participants.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Familyship founders and participant families for sharing intimate aspects of their lives in the context of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Mair, J.; Martí, I. Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthiban, R.; Qureshi, I.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Bhatt, B.; Jaikumar, S. Leveraging ICT to Overcome Complementary Institutional Voids: Insights from Institutional Work by a Social Enterprise to Help Marginalized. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Uhlaner, L.M.; Stride, C. Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; Steiner, A.; Mazzei, M.; Baker, R. Filling a void? The role of social enterprise in addressing social isolation and loneliness in rural communities. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M.R.; Vieira, L.M.; Bossle, M.B. Social innovation as a process to overcome institutional voids: A multidimensional overview. RAM Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2016, 17, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zietlow, J.T. Social Entrepreneurship: Managerial, Finance and Marketing Aspects. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2001, 9, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Stott, N. Social innovation: A window on alternative ways of organizing and innovating. Innovation 2017, 19, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, S.M. The Protean Quality of Subcultural Consumption: An Ethnographic Account of Gay Consumers. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, J.; Eichert, C.A.; Noelke, A.-I. Towards (and Beyond) LGBTQ+ Studies in Marketing and Consumer Research. In Handbook of Research on Gender and Marketing; Dobscha, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 273–293. [Google Scholar]

- Luedicke, M.K. Indigenes’ responses to immigrants’ consumer acculturation: A relational configuration analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñaloza, L. Atravesando Fronteras/Border Crossings: A Critical Ethnographic Exploration of the Consumer Acculturation of Mexican Immigrants. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstüner, T.; Holt, D.B. Dominated Consumer Acculturation: The Social Construction of Poor Migrant Women’s Consumer Identity Projects in a Turkish Squatter. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, D. Paths to Respectability: Consumption and Stigma Management in the Contemporary Black Middle Class. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 554–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, D.; Wallendorf, M. The Role of Normative Political Ideology in Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaraboto, D.; Fischer, E. Frustrated Fatshionistas: An Institutional Theory Perspective on Consumer Quests for Greater Choice in Mainstream Markets. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1234–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandikci, Ö.; Ger, G. Veiling in Style: How Does a Stigmatized Practice Become Fashionable? J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S. How Can Social Enterprise Address Disadvantage? Evidence from an Inner City Community. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2010, 22, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, C. The Fourth Sector: Creating a For-Profit Social Enterprise Sector to Directly Combat the Lack of Social Mobility in Marginalized Communities. Hastings Race Poverty Law J. 2016, 13, 349. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.J.; Donaldson, C.; Baker, R.; Kerr, S. The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well-being: A model and systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 123, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.M. Implementing a Social Enterprise Intervention with Homeless, Street-Living Youths in Los Angeles. Soc. Work 2007, 52, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berno, T. Social enterprise, sustainability and community in post-earthquake Christchurch: Exploring the role of local food systems in building resilience. J. Enterp. Communities 2017, 11, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, S.-A.; Steiner, A.; Farmer, J. Processes of community-led social enterprise development: Learning from the rural context. Community Dev. J. 2014, 50, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; De Cotta, T.; McKinnon, K.; Barraket, J.; Munoz, S.-A.; Douglas, H.; Roy, M. Social enterprise and wellbeing in community life. Soc. Enterp. J. 2016, 12, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Hunt, P.; Carson, D. Social Enterprise and Community-Based Care: Is There a Future for Mutually Owned Organisations in Community and Primary Care? King’s Fund: London, UK, 2006; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Steinerowski, A.A.; Steinerowska-Streb, I. Can social enterprise contribute to creating sustainable rural communities? Using the lens of structuration theory to analyse the emergence of rural social enterprise. Local Econ. J. Local Econ. Policy Unit 2012, 27, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Haugh, H. Beyond Philanthropy: Community Enterprise as a Basis for Corporate Citizenship. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 58, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, E.; Roy, M.J. Empowering communities? Exploring roles in facilitated social enterprise. Soc. Enterp. J. 2019, 15, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Molla, A.; Goswami, S.; Brewster, C. Green information systems use in social enterprise: The case of a community-led eco-localization website in the West Midlands region of the UK. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 1345–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, B. Exploring the meaning(s) of sustainability for community-based social entrepreneurs. Soc. Enterp. J. 2005, 1, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugh, H. Community-led social venture creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M.; Hazenberg, R. Floating down the river: Vietnamese community-led social innovation. Soc. Enterp. J. 2021, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachetti, S.; Campbell, C. Creating space for communities: Social enterprise and the bright side of social capital. In Proceedings of the IIPPE’s Fifth International Conference in Political Economy, Naples, Italy, 16–18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, G. The Long Interview: Qualitative Research Methods; Sage Publications: Sauzende Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R.V. The Field behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V. Netnography: Redefined; SAGE Publications: Sauzende Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, A.M.; Velagaleti, S.R. Outsourcing Parenthood? How Families Manage Care Assemblages Using Paid Commercial Services. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 911–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.; Fischer, E.; Kozinets, R.V. Qualitative Consumer and Marketing Research; SAGE Publications: Sauzende Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McAlexander, J.H.; Schouten, J.W.; Koenig, H.F. Marketplace Communities A Broader View of Brand Community. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, A.M.; O’Guinn, T. Brand Community. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Jarvis, O. Bridging Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Creation of New Organizational Forms: A Multilevel Model. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, M.; Verona, G.; Prandelli, E. Collaborating to create: The Internet as a platform for customer engagement in product innovation. J. Interact. Mark. 2005, 19, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, B.; Scaraboto, D. The Systemic Creation of Value Through Circulation in Collaborative Consumer Networks. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, R.; Kozinets, R.V. Lateral Exchange Markets: How Social Platforms Operate in a Networked Economy. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Rishika, R.; Janakiraman, R.; Houston, M.B.; Yoo, B. Social Dollars in Online Communities: The Effect of Product, User, and Network Characteristics. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).