The Relationships among Quality of Online Education, Learning Immersion, Learning Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement in Cooking-Practice Subject

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quality of Online Education

2.2. Learning Immersion

2.3. Learning Satisfaction

2.4. Cognitive Academic Achievement

3. Methodology

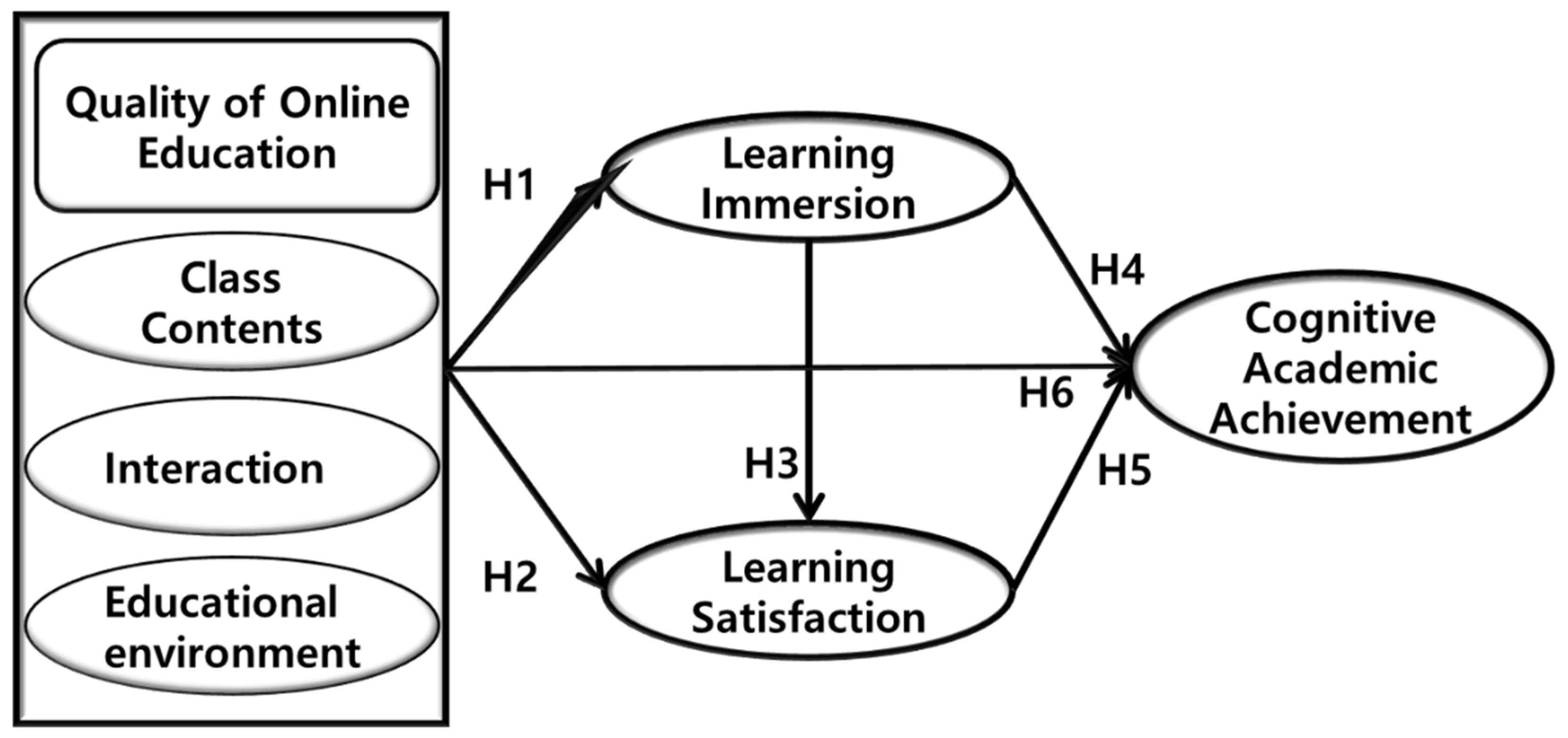

3.1. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.2. Hypotheses

3.2.1. Quality of Online Education and Learning Immersion

3.2.2. Quality of Class and Learning Satisfaction

3.2.3. Learning Immersion and Learning Satisfaction

3.2.4. Learning Immersion and Academic Achievement

3.2.5. Learning Satisfaction and Academic Achievement

3.2.6. Quality of Class and Cognitive Academic Achievement

3.3. Research Instrument

3.4. Data and Sample

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Sample

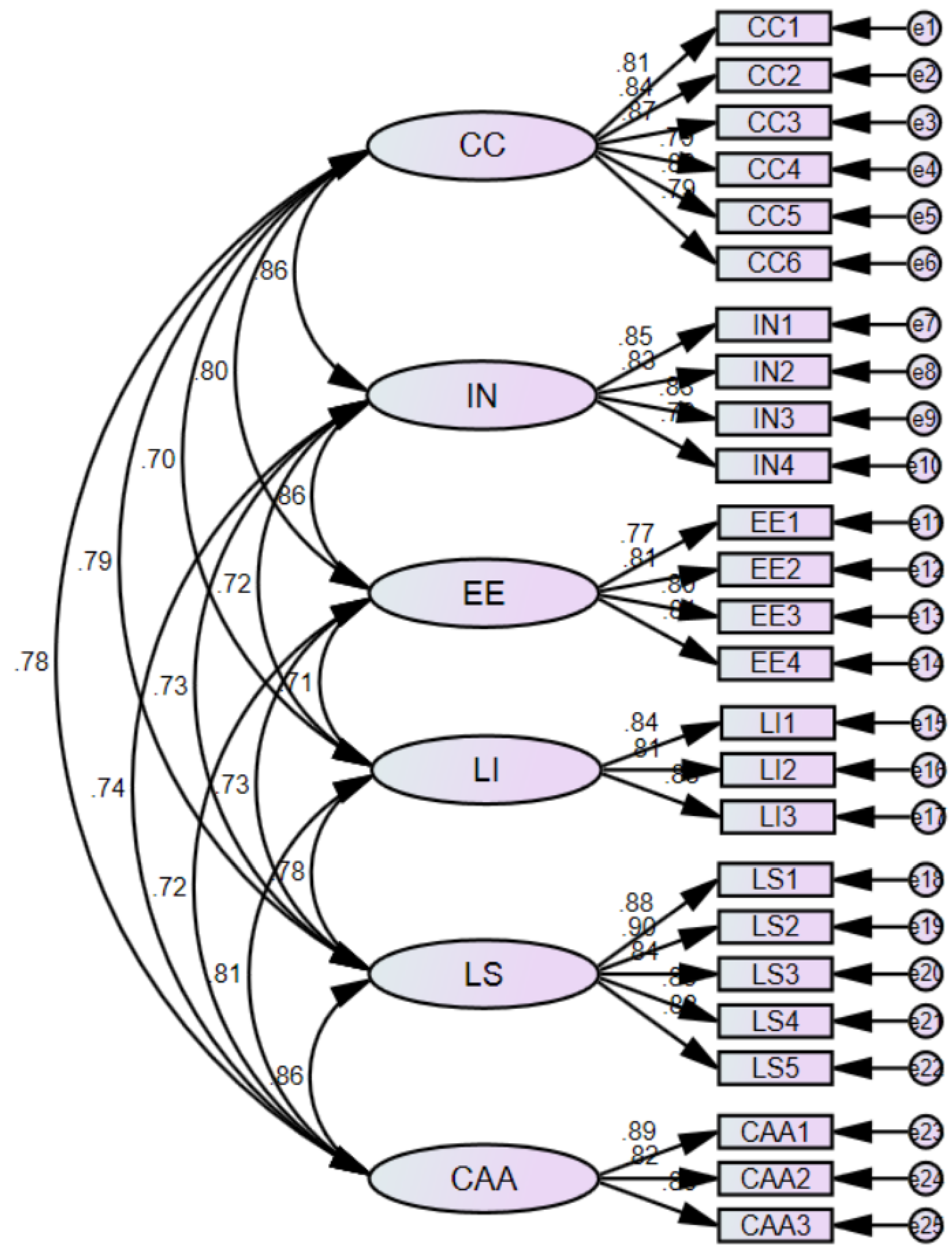

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Reliability Analysis

4.3. Correlation Analysis and Validity Analysis

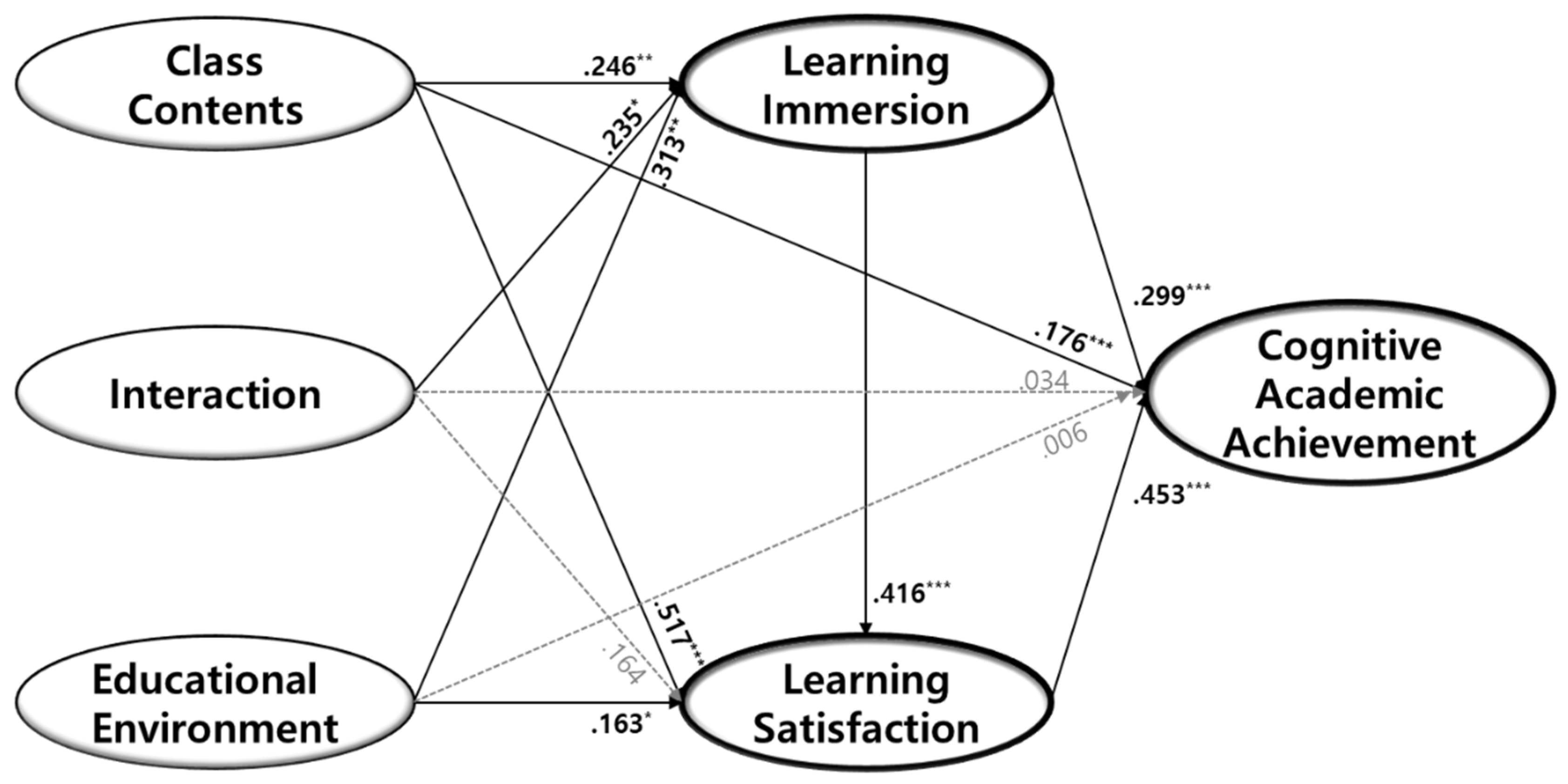

4.4. Results of the Hypotheses Verification

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.H.; Cheon, S.M. A Case Study of Online Class Operation and Instructor’s Difficulties in Physical Education as a Liberal Arts in University Due to COVID-19. J. Sports Leis. Studi. 2021, 81, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawn, S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 2020, 49, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D.R. E-Learning in the 21st Century: A Community of Inquiry Framework for Research and Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, S.B.; Wen, H.J.; Ashill, N. The determinants of students’ perceived learning outcomes and satisfaction in university online education: An empirical investigation. Dec. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2006, 4, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, H.Q.; Kim, B.K. Effects of the Amount of Images in Video Learning Has on Learning Satisfaction and Academic Achievement of Chinese University Students, Focusing on Their Learning Styles. Korean J. Converg. Humanit. 2020, 8, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, W.H.; Choi, M.J.; Hong, H.G. A case study on the operation of non-face-to-face experimental class at university with Covid-19 pandemic. J. Learn. Cent. Cur. Inst. 2020, 20, 937–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.J. The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. A Study on the Online Education of Universities Promoted by COVID-19. J. KSME 2020, 60, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Zae, S.J.; Youn, H.S. Exploring the difficulties and strategies of practicing online classes experienced by high school veteran physical education teachers in the Corona19 Pendemic. J. Digit. Converg. 2020, 20, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M. The Effects of Social Presence on Learning Satisfaction and Learning Achievement in Cyber University. e-Bus. Stud. 2019, 20, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Jeong, H.S. A study on the difference of primary language use and level of proficiency in interactive synchronous online Korean language classes. J. Inter. Net. Korean Lang. Cult. 2020, 17, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.E.; Lee, M.H. Effects of online learners’ presence perception on academic achievement and satisfaction mediated by self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and agentic engagement. Korean J. Educ. Meth. Stud. 2020, 32, 461–485. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Park, Y.J.; Yun, J.H. Exploring the “Types” through Case Analysis on Operation of Distance Education in Universities Responding to COVID-19. J. Yeolin Educ. 2020, 28, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.G.; Yun, J.S. Online Real time Lecture Operation Examples and Training Effects: Focusing on the Case of at Korea University. Korean J. Conv. Humanit. 2020, 8, 159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.Y.; Yoon, J.W. A Survey Research of Student’s Perception of Korean Language Online Video Lecture. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 11, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Bainbridge, W.S. Berkshire Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. (Vol. 1); Berkshire Publishing Group LLC: Great Barrington, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.C.; Kim, J.A. Factors that affect student satisfaction with online courses. J. Educ. Admin. 2018, 36, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T. (Ed.) The Theory and Practice of Online Learning; Athabasca University Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocariu, V.M.; Lazar, I.; Nedeff, V.; Lazar, G. SWOT analysis of e-learning educational services from the perspective of their beneficiaries. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, V.; Thurman, A. How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988–2018). Am. J. Distance Educ. 2019, 33, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Kwon, M.K.; Choi, E.K. A Study on the Instructor Perceptions and Satisfaction levels of Real-time Online Classes: Focusing on the case of Korean language program at D University. J. Dong-ak Lang. Lit. 2020, 81, 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Park, I.W. Identifying Predictability of Computer Self-Efficacy, Teaching Presence and Learner Participation on Learner Satisfaction in Online Realtime Instruction. J. Yeolin. Educ. 2012, 20, 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- Skylar, A. A comparison of asynchronous online text-based lectures and synchronous interactive web conferencing lectures. Issu. Teach. Educ. 2009, 18, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Delone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, E.J. Influence analysis of system, information and service qualities on learner satisfaction in university e-learning. J. Educ. Stud. 2010, 41, 119–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chei, M.J.; Lee, J.Y. Analysis of Structural Relationship among Instructional Quality, Academic Emotions, Perceived Achievement and Learning Satisfaction in Offline and Online University Lectures. Korean Assoc. Educ. Inf. Media 2017, 23, 523–548. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.S. The impact of students’ college experiences on students’ cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes, and instructional satisfaction. J. Educ. Admin. 2011, 29, 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, E.I. Relations among Class disturbing factors perceived by college students and professors, class participation, and class satisfaction. Korea Educ. Rev. 2012, 18, 73–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.A.; Shin, H.K.; Kim, J.W. A Study on the Influence of System Quality and Synchronization Factors for Learning Performance in e-Learning: The Mediating Effect of Learning Flow. J. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.R. Analysis of quality factors influencing learner satisfaction on mobile learning linked to e-learning in universities. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 29, 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Seo, J.T. Analysis of the Structural Relationships among Instructional Quality Factors, Learning Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement. Asia-Pac. J. Mult. Serv. Conv. Art. Hum. Soc. 2017, 7, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, Y.S. Difference of Information Quality, Service Quality, System Quality and Satisfaction between University Students and the General Public in MOOC. J. Lifelong Learn. Soc. 2018, 14, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, I.W. The Structural Relationship among Intention to Take, Quality, Learning Satisfaction, Achievement and Continued to Use Intention in K-MOOC Learning Environment. J. Educ. Inf. Med. 2019, 25, 525–549. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M. Analysis of Press Articles in Korean Media on Online Education related to COVID-19. J. Digit. Contents Soc. 2020, 21, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.S.; Ahn, G.Y. The Effects of Learning Service Quality and Interaction of Uncontact Learning in College of Culinary & Food Service on Learning Immersion and Learning Achievement. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2020, 26, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Play and intrinsic rewards. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Jeanne, N. The dynamics of intrinsic motivation: A study of adolescents. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M.; Flow, M. The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bolliger, D.U. Key factors for determining student satisfaction in online courses. Int. J. E-Learn. 2004, 3, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, H.M. Student engagement in instructional activity: Patterns in the elementary, middle and high school years. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2000, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, H. Student Engagement in Campus-Based and Online Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.K. Effects of students’ flow and cognitive Learning engagement on their Learning outcomes in online Learning. J. Korean Assoc. Educ. Inf. Med. 2011, 17, 379–397. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment. Internet High. Educ. 2000, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, K.M.; Healy, M.A. Key factors influencing student satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. J. Mark. High. Educ. 2001, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, A.W. The changing American college student: Implications for educational policy and practice. High. Educ. 1991, 22, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.M.; Chan, J. Direct and indirect effects if inline learning in distance education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2004, 35, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Kang, M.H. Structural relationship among teaching presence, learning presence, and effectiveness of e-learning in the corporate setting. Asian J. Educ. 2010, 11, 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y. Effects of self-direction, prior knowledge and delivery strategies on learner satisfaction and performance in Web-based instruction. J. Educ. Technol. 2002, 18, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y. The effects of university students’ self-directed learning ability and perceived online task value on learning satisfaction and academic achievement. Eng. Lang. Teachnol. 2017, 29, 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.; Han, T.I. A study on the variables influencing student achievement in a blended learning of college English. J. Dig. Converg. 2013, 11, 719–730. [Google Scholar]

- Rouiller, J.Z.; Goldstein, I.L. The relationship between organizational transfer climate and positive transfer of training. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 1993, 4, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Chung, O.B. A Study on the perception and the satisfaction with learning on human development and family relations area of the 6th revision of middle school Home Economics Education curriculum. J. Korean Home Econ. Educ. Assoc. 1997, 9, 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rovai, A.P. Sense of community, perceived cognitive learning, and persistence in asynchronous learning network. Internet High. Educ. 2002, 5, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.R. The Undergraduates: A Report of Their Activities; Center for the Study of Evaluation, University of Columbia: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.S.; Kim, S.Y. Validating an evaluation model to measure the effectiveness of educational programs of lifelong education centers affiliated with universities. Culi. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2011, 42, 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Roh, S.Z.; Yu, B.M. The Effects of Learner Characteristics, Teaching Presence, and Content Quality on Learning Effects in the General University e-Learning: Focused on the Mediating Effect of Learning Flow. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 13, 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, H.R.; Shin, H.C. A Study on the Influence of Non-face-to-Face Education Service Quality on Learning Commitment and Education Satisfaction: Focused on Students Majoring in Tourism. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2020, 32, 363–384. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, S.H.; Park, K.Y.; Park, A.S. The Effects of Cooking Education Service Quality on Satisfaction of Adult Learners of Lifelong Education Center. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2017, 20, 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.K.; Choi, S.H.; Ma, Z. The Mediation Effects of Learner’s Satisfaction on the Influence of Education Service Quality Perceived by Vocational Training Institute Students Major of Culinary on Learning Transfer. Tour. Res. 2020, 45, 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.U.; Um, M.Y. Gender Differences in Perceptions and Relationships among Determinants of User Satisfaction in e-Learning. Korean Manag. Rev. 2006, 35, 51–80. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, Y.J. The Effects of Contents Quality Factors on Academic Persistence in Online Education Responding to COVID-19: Focused on the Mediating Learning Flow and Satisfaction. J. Know. Inf. Technol. Syst. 2020, 15, 759–770. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, U.J.; Park, J.H. The Relationships among Learning Presence, Learning Flow, and Academic Achievement at the Cyber Universities. Asian J. Educ. 2012, 13, 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.H.; Yeo, H.K.; Jeong, H.K. The effect of Learning Motivation and Academic Self-Efficacy of University Students Majoring Tourism on Learning Flow, Academic Achievement and Learning Transfer. J. Tour. Leis. Res. 2014, 26, 451–469. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.G.; Kim, W.J.; Lee, J.K. The relationship between learning motivation, learning commitment and academic achievement of nursing students who gave non-face-to-face online lectures. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21, 412–419. [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai, S.; Blau, I. Scaffolding game based learning: Impact on learning achievements, perceived learning, and game experiences. Comput. Educ. 2014, 70, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Seo, J.H.; Lee, J.H. The influence of the educational environment of the cooking institute on the educational satisfaction and the behavior intention: Moderating effect of educational period. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2017, 23, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H. Verification of structural relationship between quality of Untact online education, academic achievement, and learning satisfaction to prepare for Post COVID. J. Foodserv. Manag. 2020, 23, 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; Ha, Y.J.; Yoo, J.W.; Kim, E.K. The Structural Relationship among Teaching Presence, Cognitive Presence, Social Presence, and Learning Outcome in Cyber University. J. Korean Assoc. Inf. Educ. 2010, 14, 175–187. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Operational Definition/Measurement | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of On-line Education | Class Contents (CC) | Information quality in terms of instructional design, such as the content of the online class, delivery method | DeLone & McLean [24] Lee & Lee [25] Jeong [28] Lee, Kim & Kim [30] Chei & Lee [26] Kim & Lee [32] |

| (CC1) Clarity of class objectives (CC2) Appropriateness of learning objectives (CC3) Adequacy of the amount of learning (CC4) Systematic content of classes (CC5) Expectations and agreements for class content, (CC6) Providing appropriate learning materials | |||

| Interaction (IN) | Communication between instructor and student | ||

| (IN1) Handling the needs of learners, (IN2) Communication between instructor and learner, (IN3) Instructor’s active problem solving (IN4) Fast and accurate feedback from instructors | |||

| Educational Environment (EE) | The level of technical and physical environment as the accuracy and efficiency of the online education system | ||

| (EE1) Ease of access to the site, (EE2) No video stuttering or noise (EE3) Ease of system menu configuration, (EE4) Appropriateness of tools for interaction | |||

| Learning Immersion (LI) | Level of concentration and intensity of interest in online learning | Marks [40] Kim, Shin & Kim [29] Choi, Yeo & Jeong [64] Lee, Kim & Lee [65] | |

| (LI1) Class time seems to be passing quickly (LI2) You can concentrate on taking classes in a private space, (LI3) Lesson content is interesting in being immersed in the classroom | |||

| Learning Satisfaction (LS) | To assess the degree of satisfaction on the online activities subjectively | Lee [49] Kim & Kang [48] Lee & Kim [17] Park [50] | |

| (LS1) Overall satisfaction with education content, (LS2) Overall satisfaction with the teaching method, (LS3) Satisfaction with professionalism in learning activities, (LS4) Satisfaction with the appropriateness of the learning level, (LS5) Overall satisfaction with online lectures | |||

| Cognitive Academic Achievement (CAA) | Perceptions about the learning outcomes achieved and the recognition that students can succeed themselves for online learning | Eom, Wen, & Ashill [4] Barzilai & Blau [66] Jeon & Kim [56] | |

| (CAA1) Learn a lot through class, (CAA2) Understand the class content well (CAA3) Online learning helps me | |||

| Demographic Characteristics | Number of subjects Learning place, Learning tool, Computer literacy, gender, grade | Lee, Seo & Lee [67] Lee [68] | |

| Characteristics | N | % | Characteristics | N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 269 | 52.8 | Type of school | college | 366 | 71.9 |

| female | 240 | 47.2 | university | 143 | 28.1 | ||

| Number of taking lecture | 1 | 42 | 8.3 | Online class method | blended | 313 | 61.5 |

| 2 | 83 | 16.3 | real-time online | 128 | 25.1 | ||

| 3 | 205 | 40.3 | non-real-time online | 68 | 13.4 | ||

| 4 or more subjects | 179 | 35.1 | |||||

| Learning tools | desktop | 135 | 26.5 | Computer skill | 20 | 3.9 | |

| laptop | 272 | 53.4 | low | 59 | 11.6 | ||

| tablet PC | 30 | 5.9 | average | 293 | 57.6 | ||

| smartphone | 68 | 13.4 | high | 102 | 20.0 | ||

| etc. | 4 | 0.8 | very high | 35 | 6.9 | ||

| Factors | Items | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | C.R. | AVE | Cronbach’s α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | |||||||

| Class Contents (CC) | CC 1 | 1.000 | 0.812 | 0.945 | 0.740 | 0.925 | ||

| CC 2 | 1.029 | 0.841 | 0.046 | 22.459 | ||||

| CC 3 | 1.131 | 0.873 | 0.048 | 23.739 | ||||

| CC 4 | 0.993 | 0.785 | 0.049 | 20.342 | ||||

| CC 5 | 1.017 | 0.826 | 0.047 | 21.875 | ||||

| CC 6 | 1.052 | 0.789 | 0.051 | 20.502 | ||||

| Interaction (IN) | IN 1 | 1.000 | 0.848 | 0.921 | 0.743 | 0.893 | ||

| IN 2 | 1.011 | 0.827 | 0.044 | 22.971 | ||||

| IN 3 | 0.969 | 0.828 | 0.042 | 22.999 | ||||

| IN 4 | 0.930 | 0.787 | 0.044 | 21.233 | ||||

| Educational Environment (EE) | EE 1 | 1.000 | 0.769 | 0.904 | 0.733 | 0.876 | ||

| EE 2 | 1.058 | 0.813 | 0.055 | 19.113 | ||||

| EE 3 | 0.952 | 0.801 | 0.051 | 18.796 | ||||

| EE 4 | 1.012 | 0.814 | 0.053 | 19.145 | ||||

| Learning Immersion (LI) | LI 1 | 1.000 | 0.839 | 0.896 | 0.742 | 0.883 | ||

| LI 2 | 0.962 | 0.813 | 0.045 | 21.454 | ||||

| LI 3 | 1.000 | 0.880 | 0.042 | 23.951 | ||||

| Learning Satisfaction (LS) | LS 1 | 1.000 | 0.881 | 0.949 | 0.789 | 0.940 | ||

| LS 2 | 1.009 | 0.899 | 0.034 | 29.824 | ||||

| LS 3 | 0.921 | 0.839 | 0.036 | 25.873 | ||||

| LS 4 | 0.998 | 0.852 | 0.038 | 26.642 | ||||

| LS 5 | 1.021 | 0.883 | 0.036 | 28.722 | ||||

| Cognitive Academic Achievement (CAA) | CAA 1 | 1.000 | 0.892 | 0.916 | 0.785 | 0.891 | ||

| CAA 2 | 0.849 | 0.819 | 0.035 | 24.229 | ||||

| CAA 3 | 1.005 | 0.861 | 0.038 | 26.582 | ||||

| M ± SD | CC | IN | EE | LI | LS | CAA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 3.73 ± 0.73 | 0.740 | |||||

| IN | 3.74 ± 0.74 | 0.845 (0.714) *** | 0.743 | ||||

| EE | 3.70 ± 0.74 | 0.804 (0.646) *** | 0.843 (0.711) *** | 0.733 | |||

| LI | 3.31 ± 0.83 | 0.697 (0.486) *** | 0.720 (0.518) *** | 0.707 (0.500) *** | 0.742 | ||

| LS | 3.66 ± 0.82 | 0.793 (0.629) *** | 0.728 (0.530) *** | 0.729 (0.531) *** | 0.779 (0.607) *** | 0.789 | |

| CAA | 3.63 ± 0.80 | 0.777 (0.604) *** | 0.738 (0.545) *** | 0.722 (0.521) *** | 0.805 (0.563) *** | 0.836 (0.699) *** | 0.785 |

| Hypotheses | Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | |||||||

| H 1-1 | CC | → | LI | 0.299 | 0.246 | 0.113 | 2.655 ** | Supported |

| H 1-2 | IN | → | LI | 0.259 | 0.235 | 0.132 | 1.969 * | Supported |

| H 1-3 | EE | → | LI | 0.376 | 0.313 | 0.117 | 3.216 ** | Supported |

| H 2-1 | CC | → | LS | 0.639 | 0.517 | 0.097 | 6.618 *** | Supported |

| H 2-2 | IN | → | LS | -0.184 | -0.164 | 0.109 | −1.688 | Rejected |

| H 2-3 | EE | → | LS | 0.200 | 0.163 | 0.097 | 2.062 * | Supported |

| H 3 | LI | → | LS | 0.424 | 0.416 | 0.052 | 8.197 *** | Supported |

| H 4 | LI | → | CAA | 0.299 | 0.299 | 0.056 | 5.370 *** | Supported |

| H 5 | LS | → | CAA | 0.444 | 0.453 | 0.062 | 7.225 *** | Supported |

| H 6-1 | CC | → | CAA | 0.214 | 0.176 | 0.099 | 2.154 * | Supported |

| H 6-2 | IN | → | CAA | 0.038 | 0.034 | 0.103 | 0.363 | Rejected |

| H 6-3 | EE | → | CAA | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.092 | 0.083 | Rejected |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | 95% Confidence Interval | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| CC ⟶ LI ⟶ CAA | 0.090 | 0.074 | 0.047 | −0.004 | 0.194 | - |

| CC ⟶ LS ⟶ CAA | 0.284 ** | 0.234 | 0.074 | 0.191 | 0.550 | Partial Mediation |

| CC ⟶ LI ⟶ LS ⟶ CAA | 0.056 * | 0.046 | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.114 | Partial Mediation |

| IN ⟶ LI ⟶ CAA | 0.078 | 0.070 | 0.062 | −0.044 | 0.204 | - |

| IN ⟶ LS ⟶ CAA | −0.082 | −0.074 | 0.062 | −0.261 | 0.010 | - |

| IN ⟶ LI ⟶ LS ⟶ CAA | 0.049 | 0.044 | 0.037 | −0.017 | 0.135 | - |

| EE ⟶ LI ⟶ CAA | 0.113 * | 0.094 | 0.059 | 0.004 | 0.247 | Complete Mediation |

| EE ⟶ LS ⟶ CAA | 0.089 * | 0.074 | 0.049 | 0.010 | 0.192 | Complete Mediation |

| EE ⟶ LI ⟶ LS ⟶ CAA | 0.071 * | 0.059 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.155 | Complete Mediation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, S.-H. The Relationships among Quality of Online Education, Learning Immersion, Learning Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement in Cooking-Practice Subject. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112152

Kim Y-J, Lee S-H. The Relationships among Quality of Online Education, Learning Immersion, Learning Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement in Cooking-Practice Subject. Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112152

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yae-Ji, and Seung-Hoo Lee. 2021. "The Relationships among Quality of Online Education, Learning Immersion, Learning Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement in Cooking-Practice Subject" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112152