Abstract

Over the last few decades, various regions have taken advantage of sport as a tool for place branding. One of the most used strategies has been sporting events, which can help to position the regions and improve their image. With regard to destination image (DI), the penetration and popularity of social media such as Instagram has opened new avenues for place promotion and has turned the users of these platforms into active agents in the promotion of DI. This study aims to explore whether the participants and organisers of small-scale sport events (SSSEs) can contribute to the creation of destination image through the content they post on Instagram. For this purpose, the content of 1315 photographs posted by SSSE participants and organisers on Instagram was analysed. The results show that the photographs related to SSSEs reproduce destination attributes of the region and, consequently, are a source of DI creation. The results also show the importance of the specific moment of the event both in the DI and in the engagement of the posts. This research provides valuable information on the management of Instagram in the context of SSSEs, on the importance of the characteristics of the starting and finishing lines and of the course of the event; and on the desirability of aligning the perspective of the organisers and participants to maximise the potential for the creation of DI through SSSEs.

1. Introduction

Sports tourism is one of the fastest growing areas within the tourism sector around the world [1]. One of the causes of this boom is sporting events, which have emerged as a powerful platform for place branding [2,3] and the improvement of destination image (DI) [4].

Many destinations have been focused for years on capturing mega sporting events, such as the Olympic Games or the FIFA World Cup, which have brought them various benefits with regard to place branding and have allowed them to reposition themselves [5,6,7]. More recently, some destinations with fewer resources and less economic capacity have used small-scale sport events (SSSEs) as an instrument to help improve their DI [8].

Furthermore, with the advent of social media and the increasing use of Instagram, it has been observed how images posted on the web can influence how the destinations are seen, experienced and remembered [9]. All of this has meant that tourist destination managers, sports events organisers and users have opened up new communication channels to project destinations and their most important characteristics [10].

In this context, it is important to study the extent to which SSSE participants and organisers can contribute to the DI. Specifically, this study asks the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the dominant attributes of the destination image of Osona as presented through SSSE participants and organisers on Instagram?

RQ2. What are the destination image attributes posted by SSSE participants and organisers influencing post engagement in Instagram?

The destination chosen to investigate this phenomenon was the region of Osona in the province of Barcelona, Catalonia. For more than five years, the administrations, companies and sports organisers of the Osona region have been working to position themselves as a sports tourism destination. Every year, Osona hosts more than 23,800 participants distributed in 95 outdoor sporting events.

The present study is structured around a review of the literature on key research concepts; a description of the methodological procedures used, with content analysis as the main technique; a section that deals with the empirical work and shows the potential of content posted on Instagram by SSSE participants and organisers as a source of DI, and how the main DI attributes affect post engagement, highlighting in both cases the importance of the event moment. With respect to the results, practical recommendations for maximising the use of SSSEs as a source of DI are proposed. In addition, finally, the limitations of the study are identified, and future lines of research are proposed.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Place Branding, Destination Branding and Destination Image

The competition between destinations to attract visitors is constant. This competition is a vehicle, in part, for the promotion of destination based on images and their attributes [11]. The association between brands and places is more recent. This practice is called place branding, “a network of associations in the consumers’ mind based on the visual, verbal, and behavioural expression of a place, which is embodied through the aims, communication, values, behaviour and the general culture of the place’s stakeholders and the overall place design” [12] (p. 5).

The management of places based on images, using marketing techniques to strengthen the brand, can mean a competitive advantage over other destinations [13]. In general, various strategies are used for marketing, branding, positioning, repositioning, and regeneration of any area or region [14]. All these techniques pursue three major goals: build brand awareness, influence the place’s image in the minds of consumers, and promote the place to its different target groups [15]. To guarantee success, the collaboration and participation of all the stakeholders in the region, both public and private, is essential [16,17,18]. Place branding offers a broad and deep perspective on the relationships between a place and its surroundings [19].

One of the sectors where place branding has been most studied is tourism [11,20], which has become a key element of brand building for cities, regions and countries [21]. Chung-Shing and Marafa [22] (p. 34) stress that “place branding cannot be solely understood through tourism, but it cannot be understood without tourism”. In fact, place branding is considered a key took in tourism marketing, providing a powerful image of the place to both visitors and investors and residents [23].

When place branding strategies are applied to tourism, the concept of destination branding is usually adopted [19]. Hanna [11] and Kotsi [24] define destination branding as an aspect of place branding in which the place is seen from the perspective of tourists and the tourist industry. Its main objective is to develop a consistent brand strategy that allows it to create a positive image of the destination, establish a clear positioning and differentiate it from its competitors [25,26], and influence the tourist decision-making process [27].

In branding a destination, marketers should select a consistent blend of elements to generate a unique identity [28]. Destinations need to identify their most attractive attributes, seek their essence and the values that make them unique to tourists and promote them through communication campaigns [29]. Pereira et al. [30] point out that the process of creating brands for destinations is related to the desired image of that destination, the experience of the destination, and the differentiation between destinations. Furthermore, destination branding must take into account hard factors, such as infrastructures, accessibility and the economy, as well as soft factors, such as the surroundings, the friendliness of the residents, art or leisure activities [31].

One of the core elements of destination branding is the creation of the image [32]. The image of the destination is the mental image that an individual has of a place [5], which is made up of the sum of beliefs, ideas and impressions that the individual has of a destination [33]. The destination image has three dimensions [34,35]: the cognitive dimension, which has to do with the tourists’ knowledge and beliefs regarding the destination attributes (DAs); the affective dimension, which is related to emotional responses to the destination; and the conative dimension, which represents the behaviour of the tourists and their intentions to return and recommend the destination. According to Stylidis et al. [36], the interaction between the cognitive and affective dimension makes up the overall destination image.

Hankinson [37] emphasises that image development is a key activity in brand creation. Thus, the destination image is understood as a concept that pre-exists the destination brand [38]. In this regard, branding improves the destination image, while the destination image is a determining factor in the choice of visitors [39,40]. At the tourism level, the destination image affects the behaviour of the visitors and their intentions to return or recommend it [14,41].

2.2. The Role of Sports in Place Branding and Destination Image

Sport plays an important role in shaping images of a place. Its universal nature, the dynamism and visibility of sport, the media interest it generates, and the greater appreciation of a healthy life linked to physical activity are some factors that explain this importance [42]. Thus, sport has been a significant leverage for many regions [2]. In fact, not only competitive and professional sport but all kinds of sport can be important in place branding processes [21].

Rein and Shields [3] suggest that sports branding is about the connection between people and their place, and there is no substitute for this relationship. They identify three platforms for a place branding strategy through sports: event, team and place. In a similar way, Lubowiecki and Basinska [21] relate sports place branding to building the brand image through a particular combination of sports, sports team, sports events, sports facilities, famous athletes, institutions or sports equipment manufacturers. All of them agree that sporting events are the current best practice of sports place branding. In fact, sport events are being used in three different approaches: as co-branding partners with the destination brand; as extensions of the destination; and as features of the destination [4]. Sporting events have also been analysed as rebranding tools, taking into account two major dimensions: the locus of the sports event, which can be local or international; and the frequency of the sports event—one-off or recurring [43].

Bodet and Lacassagne [44] explain that major sporting events can be used as a place branding tool based on the image transfer process from the event to the place. However, Kaplanidou and Vogt [45] did not find the same relationship in the reverse direction. Either way, sport can be a helpful tool to differentiate a place brand, promote brand positioning and create lasting perceptions of a destination brand [46].

Kozma [47] points to several benefits associated with sport place branding. Some of the most important are the economic revenue generated by sport events, the participants’ later return to the place, the media interest accompanying sporting events, the infrastructural development, the social impact on the residents and locals, the promotion of health, the reinforcement of the relationship between private and public sectors, and the networking between volunteers coming from various layers of society.

In the case of tourism and events, sport-related attributes can differentiate a destination from competitors [45,48,49] and can generate synergies between the destination and the event [50,51]. According to Chen and Funk [52], the image of a sports tourism destination can be treated as a composite tourism product, made up of distinctive elements of the region that hosts a sporting event. Thus, events are often used to improve the image of the destinations [53].

This is especially important since the image influences destination choice [54,55], visitor satisfaction and intention to return [8,40,54,56,57,58], and recommendation of the destination to others [40,57,58]. Furthermore, to maximise synergies between sporting events and the destination brand, they need to be hosted throughout the year and on a sustained basis [4,59].

2.3. Sports Tourism and Small-Scale Sport Events

According to Hallman et al. [60], sports tourism is a phenomenon that arises from the unique interaction of people, places and activities. Delpy [61] defines it as travelling to participate in a sport activity, to observe sport or to visit a sport attraction. However, as noted by Duglio et al. [62], sports tourism is a broad concept, since it relates to both the direct and indirect benefits of tourists travelling to actively participate in or attend a sporting event with a wide range of activities.

The sports tourism industry has grown considerably in recent decades [1,63], with sports tourism being the fastest growing tourism area [2]. In 2018, for example, it is estimated that between 25% and 30% of the business generated by tourism in the world was related to sport [64]. In Spain, in 2019 sports tourism generated 1433.8 million euros in spending by international travellers and attracted 6.2 million visitors [65].

One of the sectors that has had the biggest impact in sports tourism in recent years has been sporting events [66]. For example, data on participation in sporting events such as mountain running, endurance and ultratrail have experienced strong growth [62]. In the United States, the races counted by organisations accredited by the International Trail Running Association went from 1651 in 2015 to over 8300 in 2016. In addition, in 2018, 18.1 million athletes took part in running events in the United States [67].

Getz [68] distinguishes four categories of sporting events—mega-events, hallmark events, regional events and local events—and relates them to the value they bring to the region and the impact they generate. The first two types are an important touristic attraction and generate added value to the destination. In contrast, regional events and, especially, local events, have less capacity to generate added value and tourism.

The main benefits attributed to mega-events and hallmark events are the potential for tourist attraction [45,52], the improvement of the destination image [57,69,70,71], the capacity for economic development [72,73] and upgraded destination infrastructure [74].

However, since the early 2000s, many communities have started to realise the tourist potential inherent in small-scale sport events [69,75], and consequently the interest in organising them has increased considerably [76,77]. Some authors even point out that the potential for tourism development is higher in small-scale events than in mega-events [78], especially if they are held recurrently [79].

Minor events are events where competitors may outnumber the spectators, often held annually, with little national media interest and limited economic activity compared to the large-scale events [73]. Included in the small-scale events are Participatory Sport Events (PSEs), which are “community-based open-entry events that require participants to engage in moderate-to-high levels of energy expenditure” [80] (p. 149). PSEs prioritise participation and interaction in the end result and are characterised by their popular, non-competitive nature and challenges based on terrain, time and distance [81]. They often take advantage of existing equipment and resources, so they do not involve a very high investment [82,83,84]. Some events that could be considered PSEs are triathlons, running and trail running, cycling, open water swimming and other outdoor and adventure events [85].

Although small-scale sports events have a lower impact nationally and globally, they are especially important for the destinations that host them [40,52,86]. Faced with this situation, many communities have decided to attract and organise such events [87], aware that they represent an ideal opportunity to attract many visitors to both the event and the region [8,61,88].

2.4. Social Media in the Tourism Industry

At the level of communication, the process of creating the destination image involves three phases: the primary phase, which is based on the landscape, infrastructure, organisations and behaviours; the secondary phase, which includes information, publicity and public relations, among others; and the tertiary phase, which has to do with word of mouth [21]. Traditionally, this process was done through Destination Marketing Organisations (DMOs) [89]. However, with the current use of the Internet, the DMOs have lost control over the creation of destination images [90], and this has been transferred, in part, to users and content creators via social networks such as Instagram [91].

Social media is already part of the daily lives of millions of people around the world; they are an ideal space for users to share personal topics, including what they buy or where they go [20]. In addition, they have become an ideal marketing channel for brands [92].

With respect to tourism, they have had a considerable impact on destination promotion and are increasingly used by tourism managers in their marketing strategies [93]. In fact, social media is one of the main drivers of tourists’ choice of destination [94,95]. A total of 80% of people who want to travel ask for recommendations from their social media contacts, and 93% of visitors are influenced by the opinions of other users [92].

One of the main advantages attributed to their use is the ability to communicate directly with consumers [96] and to turn them into active subjects that contribute to brand creation [97,98]. Although initially used in a similar way to traditional media, they are now a dual channel of communication between brands and users [99]. The same authors have identified four key elements in the use of social media: they promote the creation of user-generated content (UGC); they take advantage of online interaction to establish ongoing relationships; they form virtual communities around a place to improve conversation and interaction; and they provide the opportunity to learn from clients, using the two-way interaction to receive feedback and analyse the market.

All these elements have fostered consumers’ ability to influence the decision-making of other users at a level not seen before [100] through user-generated content [101]. User-generated content refers to content posted on a publicly accessible website or social network that has been created by non-professional users [102]. Proximity between users reinforces influence between individuals because it reduces the perceived distance between the source of information and the receiver, therefore increasing trust between the sender and the person receiving the information [20]. Online user-generated content has been gaining prominence and is currently a topic of great interest in the literature on tourism [100,103,104,105,106,107,108,109].

Tourists today study the comments and criticisms of other users on the Internet, and they consider them more reliable than the information presented by DMO websites [94,110]. This has meant that today, the destination image is no longer shaped by official organisations [41], but rather through the vision of multiple online users [108]. UGC also influences brand perceptions positively, enriching both its image and the knowledge that users have of it [111].

In this context, one of the most impactful social networks is Instagram. Since its launch, over 50 billion photos have been uploaded, and 995 new images are posted every second [112]. In addition to personal uses, Instagram has also become a business communication tool thanks to the power of images, which are much more attractive than textual content [113]. From the users’ perspective, Instagram is the most popular platform among young people when making decisions prior to a trip [108].

Images and visual content are a very useful tool for examining the representation of a place, and photographs are an extremely important element in the projection of destination images [103]. Posting on Instagram, visitors perform as photographers and visualise their impressions [107]. In fact, these photographs not only communicate their preferences, but also provide information about behaviours [90].

Several studies point to Instagram’s contribution to the creation of destination images [9,91,92,110,113,114] and the choice of destination, especially among millennials, who make their choices based on how “Instagrammable” they are [115].

As noted by Yu et al. [109], another important element of social media is the popularity, the user engagement, of the posts. This can be measured by two variables: the number of likes and the number of comments [107,116]. Images and videos are the types of posts that tend to generate most likes and comments [116]. Furthermore, the images with most likes tend to represent places of interest to the community and in turn increase the interest of other users in the destination [117].

3. Materials and Methods

This research is based on the analysis of visual contents posted on Instagram by the organisers and participants in the four outdoor sporting events in the Osona region with most participants.

To answer the research questions, a content analysis was carried out. Content analysis is an unobtrusive and replicable method [118,119] which has been used in a wide variety of sport management research.

This method is especially useful in the analysis of social media posts [9], and is the most frequently used method in tourism research of visual images [115] and in destination image [102,105,113,115,119].

In short, according to Stepchenkova et al. [105] (p. 592), content analysis “’breaks’ a picture into several attributes (or categories) guided by what is depicted on a photo and takes these representations at face value”.

3.1. Codebook

A codebook was developed specifically for the purpose of this study based on previous literature. The unit of analysis was each individual photo posted on Instagram. The codebook was divided between three blocks: cognitive dimension, affective dimension and post engagement (Table 1).

Table 1.

Codebook based on previous research.

The cognitive dimension comprises 18 destination attributes divided into four categories: nature-, culture-, people- and event-related content. The first three categories are based on the proposals of Iglesias-Sánchez et al. [9], Mak [102], Nixon [114], and Aramendia-Muneta et al. [115]. The fourth category was developed following the recommendations of three professors specialised in sports management and includes elements specific to the organisation of the event. It considers the event moment that describes the moment of the event captured in the photo (before the race, related to the starting line, during the race, related to the finishing line, after the race, and others), elements of the event prize (t-shirts, runner’s bag, gifts, the numbers, diplomas, medals and trophies) and the aspects of the event infrastructure (tents, starting or finishing line arch, fences, podiums and photocalls, signage and refreshments).

With regard to the affective dimension, as proposed by Peters [120] and Sun et al. [119], it comprises two dimensions: subsuming emotions (joy and happiness, calm and serenity, excitement and challenge, and sadness and nostalgia) and tonality (positive, neutral and negative).

Finally, the engagement of the posts was analysed based on Kuhzady [113] through the number of likes and comments.

3.2. Data Collection

Two sources of image generation were considered for this study. On the one hand, the posted contents by the race participants were analysed through the hashtags associated with each event. Hashtags, as Gon [121] attests, bring together content related to a specific topic, generate online discussions and make posts available to other users. In addition, on the other hand, the posts generated by the organisers of these events, collected through the official accounts of each event, were studied.

A total amount of 1315 pictures posted between January 1 and December 31, 2019, were coded. A total of 383 of them were posted by the events’ official accounts (Table 2) and 932 by the event participants (Table 3). The images were downloaded in October 2020 using the software 4 K Stogram.

Table 2.

Event organiser accounts monitored.

Table 3.

Event-related hashtags monitored.

3.3. Data Analysis

Analysis of the images was based on the observation of two expert coders in sporting events, with previous experience in the use of Instagram and content analysis. A random sample of 150 images was used to test reliability between coders. Intercoder reliability was 92%, a value higher than the 0.9 recommended by Neuendorf [122].

All the images were then identified and indexed in a database that included analysis of the cognitive dimension, the affective dimension and engagement. All the elements of the cognitive dimension were considered to be destination attributes (DA), except for the unique presence of the elements ‘people racing’ and ‘people others’, because they did not allow us to relate the image with the specific destination. Finally, once the photographs were analysed, general metrics were developed.

4. Results

4.1. Destination Attributes

The images of the events posted on Instagram contain for the most part (89.12%) distinctive elements of the destination that hosts them. In fact, in many cases the images contain several Das (Figure 1). Only one distinctive element was observed in 26.8% of the images, two in 26.7%, three in 32% and four or more in 8% of the images. (Table 4). Analysed separately, users’ photographs have almost the same number of destination attributes on average (2.2) as those of the organisers (2.3).

Figure 1.

Examples of images with different destination attributes: (a) Forests, mountains and countryside; (b) Forests, water and cultural heritage.

Table 4.

Number of destination attributes in the photographs.

4.2. Cognitive Dimension

Regarding the cognitive dimension, the presence of the four categories analysed is also very similar in the photographs of the organisers and users (Table 5). The most common category in the photographs is that of people. This category appears in almost 9 out of 10 photographs (87% users and 88% organisers), followed by nature (65 and 63%, respectively), culture (41% in both) and event (35% and 39%).

Table 5.

Presence of the categories in the photographs.

Regarding the presence of each of the elements that make up the different categories (Table 6), the most common element in the images is that of ‘people racing’ (69% in the photos of the users and 67% in those of the organisers). This element is followed by ‘forests’ (45% and 43%), ‘atmosphere’ (31% and 38%), ‘infrastructure’ (31% and 34%), ‘urban’ (31% and 32%) and ‘mountains’ (27% in both groups).

Table 6.

Distribution of the destination attributes in each category.

The destination attributes projected from the analysed Instagram accounts show an image of Osona, in relation to the nature dimension, predominantly linked to forests but also with a considerable presence of the element ‘mountains’ (27%) and ‘countryside’ (18% and 19%). The element ‘water’ appears in only one in ten photographs, while the element ‘animals’ is almost residual (2%).

With regard to the ‘cultural’ dimension, the presence of elements linked to ‘urban’ aspects (31% and 32%), a lower presence of elements of ‘cultural heritage’ (9% and 7%), and a reduced presence of elements ‘gastronomy’ (3% and 5%) stand out.

Finally, in the ‘event’ dimension, the presence of photographs that contain elements related to the event’s infrastructure and aspects related to the ‘prize’ element (7% and 8%) stand out.

4.3. Event Moment and Destination Attributes

Determining the moment (Figure 2) that the photographs captured a key variable in the analysis of the image projected through small-scale sport events. Significant differences are observed depending on the moment (Table 7 and Table 8). The moment with most photographs is that of ‘racing’, with 51% of the users’ photographs (and 44% those of the organisers) capturing this moment. The other moment highlighted, especially by the organisers (33%), is the variable ‘others’. The moment of arriving at the finishing line and the post-race space linked to the delivery of prizes and gifts were two moments highlighted by the users, not the organisers (10% and 11%, respectively). The other moments had percentages under 10 for both and organisers and users.

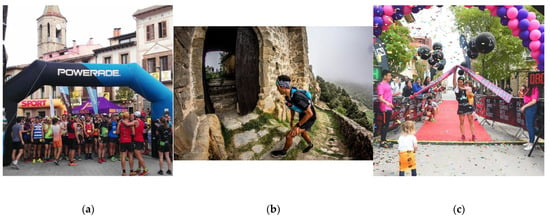

Figure 2.

Examples of moments of the images: (a) Starting line; (b) Racing; (c) Finishing line.

Table 7.

Categories in relation to the event moment. Users.

Table 8.

Categories in relation to the event moment. Organisers.

When the categories are analysed in relation to the moment of the race, big differences between and within categories were found. The only category with constant values was that of ‘people’, which obtained values close to 100% in every moment, except in the moment ‘others’ (44% in users and 70% in organisers). The ‘nature’ category obtained its highest value in the ‘racing’ moment (95 and 99%), but drops drastically when the moment is the finishing or the starting line. In these cases, the presence of nature elements did not exceed 6% in users and was non-existent in the organisers. This presence increases when the moment is ‘after the finishing line’ (28% users and 46% organisers).

A very different behaviour can be observed in the ‘culture’ category (Table 9). In the racing moment, its presence, with the combined data of organisers and participants, drops to 16%, while at the start and finish it reaches values close to 100%. However, the results broken down by elements within this category show that of the 382 DAs collected from ‘culture’, almost no element of ‘cultural heritage’ (100 of the elements of ‘culture’) appears at the ‘starting’ and ‘finishing line’ moments; and in contrast, its presence reaches 61% during the race and 24% at ‘other’ moments.

Table 9.

Distribution of cultural heritage attributes based on event moment.

4.4. Affective Dimension

With respect to the affective dimension (Figure 3), there are few differences between participants and organisers. With regard to emotions (Table 10), 47% of the participants’ posts and 51% of the organisers evoke joy and happiness. To a lesser extent, posts that represent excitement are observed (40% in participants and 39% in organisers).

Figure 3.

Emotions in the photographs: (a) Joy and happiness; (b) Challenge and excitement.

Table 10.

Emotions in the photographs.

With regard to tone (Table 11), the positivity that the analysed images emanate, both of the participants (90%) and organisers (94%), stands out. It is also notable that in neither case is a negative tone transmitted.

Table 11.

Tone of the photographs.

4.5. Post Engagement

In terms of engagement (Figure 4), the analysed images received a total of 189,408 likes and 6002 comments (Table 12). The difference in likes and comments is one of facts that most stands out. On average, the likes received by the organisers (244.5) double those of the users (127). In contrast, participants receive almost two more comments per post (5.6) than the organisers (3.8).

Figure 4.

Photographs with more engagement: (a) post with more likes; (b) post with more comments.

Table 12.

Post engagement: likes and comments.

4.5.1. Engagement and Destination Attributes

The number of destination attributes that appear in the images also affects the engagement of the posts (Table 13). In the case of the users, the photographs that generated the most interaction were those containing two DAs (144.42), followed by those containing only one (128.06). In contrast, the posts of the organisers with the most likes were those that included four DAs (260.43), followed by those with two (235.48).

Table 13.

Engagement based on DAs.

The comments were also affected by the number of destination attributes. In the case of the participants, images with five attributes were the ones that received the most comments (9.88), followed by those with four (7.27). This phenomenon was not repeated with the organisers. The photographs that generated the most comments were those that contained two DAs (6) and those that contained one (4.20).

4.5.2. Engagement and Categories

With regard to the categories of the cognitive dimension, certain differences were observed between the participants and organisers (Table 14). Regarding the participants, there was only an average difference of 7.67 likes between the elements that generated most likes (people) and least likes (nature). In contrast, the difference in likes between the images posted by the organisers is notable. Images with cultural elements received the most likes (288.07), followed by those with attributes of the event (278.89). Nature was the category with the least likes (215.2).

Table 14.

Engagement based on the category.

The average of comments varied between participants, with a difference of 2.38 comments between images with elements of culture (7.15) and of nature (4.77). Among organisers, the average number of comments is similar in all four dimensions.

4.5.3. Engagement and the Specific Moment of the Event

The images that generated most likes corresponded to the ‘finishing line’ moment, both in those of the participants (169.1 on average), and in those of the organisers (311.6). In addition, only in the case of the organisers’ images did the ‘starting line’ moment have the same number of likes (310.8) (Table 15).

Table 15.

Likes based on the moment.

The comments presented different results. The moments ‘before the race’ (9.2), ‘finishing line’ (8.4) and ‘after the race’ (8.3) showed the highest values in the participants’ photographs, while the ‘others’ (4.2) and ‘racing’ (4.1) were the two moments with most likes in those of the organisers.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This is the first article to look specifically at the role of participants and organisers of small-scale sport events in the creation of DI through their posts on Instagram.

In line with previous research [9,27,41,91,110,113,114], they show the role of Instagram as a platform for DI generation. The results of the study show how the contents posted by both the participants and the SSSE organisers also contribute to the creation of destination image, both of which stand as an alternative to the DMOs in the generation of the DI.

Several authors recommend that all the stakeholders involved in the creation of the DI promulgate a coherent and unified proposal [17,18,91]. The elements that make up the proposed cognitive and affective dimensions [35] used in this study to analyse the DI present very similar results in both organisers and users. This fact means that the SSSEs are events that need to be considered when projecting the DI in a homogenous way among the different stakeholders. To this must be added the fact that when an event is paired with a destination, a synthesis between the two takes place [32] in such a way that the combination of both aspects makes the SSSEs appealing platforms for the creation of place branding.

With regard to the destination attributes projected by the SSSEs, the results show the preponderance of the nature and urban elements of the DI. These data are consistent with other studies of image analysis projected on Instagram by both users and DMOs focused primarily on tourist destinations [9,102,113]. However, there are differences, with much lower results in the SSSEs of the ‘cultural heritage’ and ‘gastronomy’ elements.

This article also contributes to the literature on small-scale sport events and the creation of DI by showing that the moment of the race that the images capture is a key element in the projected DI. The moment affects both the destination attributes and post engagement. The ‘racing’ moment, present in half of the photographs analysed, stands out for the high presence of ‘nature’ elements. It is also the only moment in which ‘cultural heritage’ elements are present. In contrast, these two elements hardly appear at all in the images related to the starting and finishing lines of the SSSEs, where the aspects of the urban environment are the most projected. Unfortunately, the absence of other similar studies makes it impossible to compare these results with other research.

Another contribution of the article lies in the affective dimension, where the results are very similar to those of the studies where the DI projected by users on social media was analysed [9,102]. Thus, SSSE photographs show an exclusively positive tone and almost half are associated with the emotions of ‘joy and happiness’. However, the main and outstanding difference with the other studies lies on the high presence—one in every two posts—of the emotion of ‘excitement’. This aspect needs to be highlighted since it points to the potential of SSSEs to position the sports destinations as challenging and exciting regions.

With respect to engagement, the results show that the organisers’ posts receive more likes than those of the participants, while the participants’ posts receive more comments. These results are in line with what Russman and Svensson [123] explain when they point out that the likes and comments allow us to discern whether engagement with the audience on Instagram is one-way and related to self-presentation (likes) or bidirectional, which includes feedback from other Instagrammers (comments). The difference between the type of engagement between organisers and users would be explained, as Aramendia-Muneta et al. [115] point out, by the greater effort required to leave a comment and the less personal and affective connection of the other Instagrammers with the organisers compared to the users.

The results of engagement, based on the ‘likes’, shows different data depending on the dimension, coinciding with the work of Aramendia-Muneta et al. [115], which stated that the presence of certain attributes has a greater impact than others on the number of likes obtained and differences depending on the users and organisers. Thus, the users’ images with the most likes are those in which the ‘people’ dimension is present, coinciding with the results of Bakhshi et al. [124] and Ferwerda et al. [125]; while those of the organisers with most likes are those in which the ‘culture’ and ‘event’ dimensions are present. As for the participants’ comments, their focus is on the ‘culture’ dimension.

All these results indicate, as we have pointed out regarding the presence of destination attributes, a clear influence of the moment of the event on engagement as well. Thus, the greater engagement in the ‘culture’ and ‘event’ dimensions may be due, not so much to these destination attributes, but rather to the fact that the ‘finishing line’ illustrates passing the challenge of the race. In addition, consequently, it is what most Instagrammers choose to comment on. In this regard, it is key for SSSE organisers to prepare the destination attributes they wish to promote, bearing in mind the different moments of the race.

Ultimately, in line with Hemmonsbey and Maloney [46], from a strategic perspective, to maximise the potential for place branding creation of the SSSEs, similar approaches between organisers, participants and DMOs should be supported.

5.1. Practical Implications

The results of this article offer several practical implications for destination managers and SSSE organisers. First, it is advisable to align and coordinate the communication strategies of DMOs and organisers on social media and to encourage participants to share the photographs provided by the organisation through official hashtags of the events.

Furthermore, given that the moment of the race with most images is when the participants are running, the organisers should design the course, and the provisioning areas, taking into account the combination of unique landscapes and the appearance of distinctive historical and heritage attractions of the destination. In addition, it would be recommendable to place the photographs of the event in these areas of cultural and natural interest.

In a similar vein, given that the photographs relating to the ‘finishing line’ and ‘after the race’ moments are those that generate most engagement, the organisers could place the starting and finishing lines around singular cultural and heritage elements. Coinciding with the starting and finishing lines of the participants, traditional shows and entertainment activities could be set up to showcase the area’s culture.

Moreover, it is important to consider that that the elements related to the event infrastructure (podiums, photocalls, finishing line arches, etc.) that frequently appear in the photographs, are useful spaces to give visibility to the distinctive elements of the region.

The results of this study are also instructive for the management of promoted posts, which are becoming increasingly popular on Instagram [126]. Through promoted posts, organisers and DMO managers can reach new users and promote both the event and the destination. To do this more effectively, organisers should take photographs showing distinctive attributes of the destination combined with different moments of the race, mainly those related to racing and the finishing line.

To make the most of Instagram’s potential to create DI, the organisers could encourage participants to share their experiences in relation to the most distinctive and unique attributes of the area (cultural heritage, natural elements, etc.). Furthermore, to achieve higher levels of participation, these posts could be promoted through extrinsic incentives such as raffles, prizes, or registrations for the next editions of the event.

Finally, from the users’ perspective, Instagram can be useful in two ways. On the one hand, it offers them the possibility of accessing content generated by other participants and event organisers about key elements in the choice of the event and destination (the route, the atmosphere or the landscape) [127]. On the other hand, Instagram gives them the opportunity to project their vision of DI, to influence the decisions of their followers through the photographs they share, and to achieve higher levels of engagement depending on the attributes present in the photographs.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study extends the knowledge about the role of content shared by participants and organisers of sporting events as a source of destination image creation.

Despite the results of this exploratory research, further studies are required. In particular, this phenomenon should be further investigated in other destinations and in different types of events (recurring and non-recurring, individual and team sports, indoor and outdoor, etc.).

Another perspective that could be included in future research is that of DMOs. The image projected by participants and event organisers could be compared with that of the DMOs of the area to see if they match.

Finally, with regard to post engagement, only the attributes of DI have been considered in this research. Future research could incorporate variables such as the time of day when the image is uploaded, the type of content, the number of hashtags or the content of the text that accompanies the images [128].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.T. and A.J.; methodology, I.T. and A.J.; software, I.T.; validation, I.T and A.J.; formal analysis, I.T.; investigation, I.T and A.J; data curation, I.T.; writing—original draft preparation, I.T.; writing—review and editing, I.T. and A.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Universitat de Vic—Universitat Central de Catalunya (protocol code 113/2020 approved on 22 April 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Instagram accounts and hashtags described within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aicher, T.; Newland, B. To explore or race? Examining endurance athletes’ destination event choices. J. Vacat. Mark. 2017, 24, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richelieu, A. A sport-oriented place branding strategy for cities, regions and countries. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 8, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rein, I.; Shields, B. Place branding sports. Strategies for differentiating emerging, transitional, negatively viewed and newly industrialised nations. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2007, 3, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalip, L.; Costa, C. Sport Event Tourism and the Destination brand: Towards a General Theory. Sport Soc. Cult. Commer. Media Politics 2005, 8, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H.; Qi, C.; Zhang, J. Destination Image and Intent to Visit China and the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, G.; Smith, A.; Assaker, G. Revisiting the host city: An empirical examination of sport involvement, place attachment, event satisfaction and spectator intentions at the London Olypmics. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-K.; Lee, Y.-K.; Lee, B. Korea’s destination image formed by the 2002 World Cup. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yim, B.; Tuo, Z.; Zhou, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, J. “One Event, One City”: Promoting the Loyalty of Marathon Runners to a Host City by Improving Event Service Quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Correia, M.B.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. Instagram as a Co-Creation Space for Tourist Destination Image-Building: Algarve and Costa del Sol Case Studies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huertas, A.; Marine-Roig, E. Destination Brand Communication Through the Social Media: What Contents Trigger Most Reactions of Users? In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, Lugano, Switzerland, 3–6 February 2015; pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J.; Keegan, B. Place and Destination Branding: A Review and Conceptual Mapping of the Domain. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 18, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Braun, E. Branding a City: A Conceptual Approach for Place Branding and Place Brand Management. In Proceedings of the 39th EMAC Annual Conference, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 1–4 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J. Practitioners views on the essence of place brand management. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2012, 8, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Panda, R.K. Place branding and place marketing: A contemporary analysis of the literature and usage of terminology. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2019, 16, 255–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S. Measuring place brand equity with the advanced Brand Concept Map (aBCM) method. Place Branding Public Dipomacy 2014, 10, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Millan-Celis, E.; Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C. Importance of Social Media in the Image Formation of Tourist Destinations from the Stakeholders’ Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Grace, D.; Perkins, H. City branding research and practice: An integrative review. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M. From ‘necessary evil’ to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2012, 5, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briciu, V. Differences between place banding and destination branding for local brand strategy development. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. 2013, 6, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Acuti, D.; Grazzini, L.; Mazzoli, V.; Aiello, G. Stakeholder engagement in green place branding: A focus on user-generated content. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubowiecki, A.; Basinska, A. Sport and tourism as elements of place branding: A case study on Poland. J. Tour. Chall. Trends 2011, 4, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Shing, C.; Marafa, L. Branding Places and Tourist Destinations: A Conceptualisation and Review. In The Branding of Tourist Destinations: Theoretical and Empirical Insights; Camilleri, M., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Plumed, M.; Iñiguez, T.; Elboj, C. Place branding process: Analysis of population as consumers of destination image. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2017, 11, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsi, F.; Stephens, M.; Michael, I.; Zoega, T. Place branding: Aligning multiple stakeholder perception of visual and auditory communication elements. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L. Cooperative branding for rural destinations. Ann. Toursim Res. 2002, 29, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Hyunjung, L.; Hyunjung, H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camprubí, R.; Planas, C. El storytelling en la marca de destinos turísticos: El caso de Girona. Cuad. Tur. 2020, 46, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boo, S.; Busser, J.; Baloglu, S. A model of customer-based brand equity and its application to multiple destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization and European Travel Commission. Handbook on Tourism Destinations Branding; WTO: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.; Correia, A.; Schutz, R. Destination Branding: A Critical Overview. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 13, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Pride, R. Destination Brands: Managing Place Reputation; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Wong, I.; Tan, X.; Wu, D. The role of food festivals in branding culinary destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographincal Location upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W. Image formation process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Oom, P.; da Costa Mendes, J. The Cognitive-Affective-Conative Model of Destination Image: A Confirmatory Analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Shani, A.; Belhassen, Y. Testing an integrated destination image model across residents and tourists. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hankinson, G. Towards Effective Place Branding Management: Branding European Cities and Regions; Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., Ashworth, G., Eds.; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2010; pp. 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, S. Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 6, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruiz-Real, J.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J. Destination branding: Opportunities and new challenges. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. Exploring a suitable model of destination image: The case of a small-scale recurring sport event. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 35, 1287–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefieva, V.; Egger, R.; Yu, J. A machine learning to cluster destination image on Instagram. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matecki, P. Public Relations in Sport; Godlewski, P., Trebecki, J., Rydzak, W., Eds.; SportWin: Poznan, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Herstein, R.; Berger, R. Much more than sports: Sports events as stimuli for city re-branding. J. Bus. Strategy 2013, 34, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, G.; Lacassagne, M. International place branding through sporting events: A British perspective of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Vogt, C. The interrelationship between Sport Event and Destination Image and Sport Tourists’ Behaviours. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmonsbey, J.; Maloney, T. Brand messages that influence the sport tourism experience: The case of South Africa. J. Sport Tour. 2020, 24, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G. Sport as an element in the place branding activities of the local governments. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2010, 6, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman, K.; Breuer, C. Images of rural destinations hosting small-scale sport events. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2011, 2, 218–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Reimaging the city: The value of sport initiatives. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 217–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xing, X.; Chalip, L. Effects of Hosting a Sport Event on Destination Brand: A Test of Co-branding and Match-up Models. Sport Manag. Rev. 2006, 9, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Chalip, L.; Jago, L.; Mules, T. Destination Branding; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Funk, D. Exploring Destination Image, Experience and Revisit Intention: Comparison of Sport and Non-Sport Tourist Perceptions. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainofli, G.; Marino, V. Destination beliefs, event satisfaction and post-visit product receptivity in event marketing. Results from a tourism experience. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, S.; Khazaei, J.; Jaberi, A.; Salehzadeh, R.; Asadi, H. Factors influencing sport tourists’ revisit intentions: The role and effect of destination image, perceived quality, perceived value and satisfaction. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2015, 27, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinting, E.; Yusof, A.; Chen, C. Understanding sport tourists’ motives and perceptions of Sabah, Malaysia as a sport tourist destination. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2013, 13, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faullant, R.; Matzler, K.; Füller, J. The impact of satisfaction and image on loyalty: The case of Alpine ski resorts. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2008, 18, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanovic, I.; Matic, R.; Alexandris, K.; Maksimovic, N.; Milosevic, Z.; Drid, P. Destination image, sport event quality, and behavioral intentions: The cases of three World Sambo Championships. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Grivel, E. Antecedents of sport event satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The role of sport identification, motivation, and place dependence. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, V. Integrating sport events into destination development: A tourism leveraging event portfolio model. In Proceedings of the 2018 EURAM Annual Conference, Reykjavic, Iceland, 19–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman, K.; Kaplanidou, K.; Breuer, C. Event image perception among active and passive sports tourists at marathon races. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2010, 12, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpy, L. An overview of sport tourism: Building towards a dimensional framework. J. Vacat. Mark. 1998, 4, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Beltramo, R. Estimating the Economic Impacts of a Small-Scale Sport Tourism Event: The Case of the Italo-Swiss Mountain Trail CollonTrek. Sustainability 2017, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peric, M. Managing sports experiences in the context of tourism. UTMS J. Econ. 2015, 6, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. World Travel & Tourism Council Annual Report; World Travel & Tourism Council: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Anuario de Estadísticas Deportivas; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- Fotiadis, A.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.; Huan, T. Attracting athletes to small-scale sports events using motivational decision-making factors. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5467–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Running USA. The State of Running 2019. 2021. Available online: https://runrepeat.com/state-of-running (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Getz, D. Event tourism: Definition, evolution, and research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Gibson, H. Predicting Behavioral Intentions of Active Event Sports Tourists: The Case of a Small-scale Recurring Sports Event. J. Sport Tour. 2010, 15, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinch, T.; Holt, N. Sustaining places and participatory sport tourism events. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 1084–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouder, R.; Clark, J.; Fenich, G. An exploratory study of how destination marketing organizations pursue the sports tourism market. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, G.; Chalip, L. Tourism Management: Analysis, Behaviour, and Strategy; Woodside, A., Martin, D., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008; pp. 318–338. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, H.; Kaplanidou, K.; Jin, S. Small-scale event sport tourism: A case study in sustainable tourism. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; Fairley, S. What about the event? How do tourism leveraging strategies affect small-scale events? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.; Norman, W. Estimating the economic impacts of seven regular sport tourism events. J. Sport Tour. 2003, 8, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzetzis, G.; Alexandris, K.; Kapsampeli, S. Predicting visitors’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions from service quality in the context of a small-scale outdoor sport event. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2014, 5, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Vassialidis, C.; Yeh, S.P. Participant’s preferences for small-scale sporting events: A comparative analysis of a Greek and Taiwanese cycling event. EuroMed J. Bus. 2016, 11, 232–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, P.; Kelly, S. ‘Non-local’ Masters Games Participants: An Investigation of Competitive Active Sport Tourist Motives. J. Sport Tour. 2006, 11, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Poczta, J. A Small-Scale Event and a Big Impact—Is This Relationship Possible in the World of Sport? The Meaning of Heritage Sporting Events for Sustainable Development of Tourism—Experiences from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crofts, C.; Schofield, G.; Dickson, G. Women-only mass participation sporting events: Does participation facilitate changes in physical activity? Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, G. The Gran Fondo and Sportive Experience: An Exploratory Look at Cyclists’ Experiences and Professional Event Staging. Event Manag. 2014, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higham, J. Commentary–Sport as an Avenue of Tourism Developlment: An Analysis of the Positive and Negative Impacts of Sport Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 1999, 2, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczycki, C.; Halpenny, E. Sport Cycling tourists’ setting preferences, appraisals and attachments. J. Sport Tour. 2014, 19, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, C. Comparative urban research and mass participation running events: Methodological reflections. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kenelly, M. “We’ve never measured it, but it brings in a lot of business”: Participatory sport events and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 3, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertella, G. Designing small-scale sport events in the countryside. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2014, 5, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buning, R.; Gibson, H. Exploring the Trajectory of Active-Sport-Event Travel Careers: A Social Words Perspective. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrusa, J.; Lema, J.; Seongseop, S.; Botto, T. The Impact of Consumer Bheavior and Service Perceptions of a Major Sport Tourism Event. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 14, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo, P.; Moreno-Gil, S. Analysis of the projected image of tourism destinations on photographs: A literature review to prepare for the future. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, I.; Fossgard, K.; Vidar, J. Do visitors gaze and reproduce what destination managers wish to commercialise? Perceived and projected image in the UNESCO World Heritage area “West Norwegian Fjords”. Int. J. Digit. Cult. Electron. Tour. 2018, 2, 294–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, H.; Putit, N. Express marketing of tourism destinations using Instagram in social media networking. In Hospitality and Tourism: Synergizing Creativity and Innovation in Research; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2014; pp. 471–474. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, N.; Cohen, S.; Scarles, C. The power of social media storytelling in destination branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laurell, C.; Björner, E. Digital festival engagement: On the interplay between festivals, place brands, and social media. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchinaka, S.; Yoganathan, V.; Osburg, V.-S. Classifying residents’ roles as online place-ambassadors. Tour. Manag. 2019, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G. Age and gender differences in online travel reviews and user-generated-content (UGC) adoption: Extending the technology acceptance model (TAM) with credibility theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevin, E. Places going viral: Twitter usage patterns in destination marketing and place branding. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2013, 6, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.T.; Sharmin, F.; Badulescu, A.; Gavrilut, D.; Xue, K. Social Media-Based Content towards Image Formation: A New Approach to the Selection of Sustainable Destinations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Burns, A.; Hou, Y. An Investigation of Brand-Related User-Generated Content on Twitter. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleave, E.; Arku, G.; Sadler, R.; Kyeremeh, E. Place Marketing, Place Branding, and Social Media: Perspectives of Municipal Practitioners. Growth Chang. 2017, 48, 1012–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Johnson, K. Power of consumers using social media: Examining the influences of brand-related user-generated content on Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.; Samiei, N. The effect of electronic word of mouth on brand image and purchase intention: An empirival study in the automobile industry in Iran. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2012, 30, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, A. Online destination image: Comparing national tourism organisation’s and tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paül, D. Characterizing the location of tourist images in cities. Differences in user-generated images (Instagram), official tourist brochures and travel guides. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 73, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatanti, M.; Suyadanya, I. Beyond User Gaze: How Instagram Creates Tourism Destination Brand? Procedia–Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 211, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Zhan, F. Visual destination images of Peru: Comparative content analysis of DMO and user-generated photography. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.; Au, N.; Law, R. Predicting the intention to use consumer-generated media for travel planning. Tour. Manag. 2013, 35, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swani, K.; Milne, G.; Brown, B.; Assaf, G.; Donthu, N. What messages to post? Evaluating the popularity of social media communications in business versus consumer markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 62, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkaris, E.; Neuhofer, B. The influence of social media on the consumers’ hotel decision journey. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2017, 8, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yuqing, S.; Wen, J. Coloring the destination: The role of color psychology on Instagram. Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.; Ismail, H.; Lee, S. From desktop to destination: User-generated content platforms, co-created online experiences, destination image and satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Sarvary, M. Differentiation with User-Generated Content. Manag. Sci. 2014, 64, 898–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omnicore. Instagram Statistics. 2021. Available online: https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/ (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Kuhzady, S.; Ghasemi, V. Pictorial analysis of the projected destination image: Portugal on Instagram. Tour. Anal. 2019, 24, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, L.; Popova, A.; Önder, I. How Instagram influences visual destination image: A case study of Jordanand Costa Rica. In Proceedings of the eTourism Conference (ENTER2017), Rome, Italy, 24–26 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aramendia-Muneta, M.A.; Olarte-Pascual, C.; Ollo-López, A. Key Image Attributes to Elicit Likes and Comments on Instagram. J. Promot. Manag. 2021, 27, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, F.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Cañabate, A.; Lebherz, P. Factors influencing popularity of branded content in Facebook fan pages. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhina, K.; Rakitin, S.; Visheratin, A. Detection of tourists attraction using Instagram profiles. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 108, 2378–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffe, D.; Lacy, S.; Watson, B.; Fico, F. Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Tang, S.; Liu, F. Examining Perceived and Projected Destination Image: A Social Media Content Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K. Social Media Metrics–A Framework and Guidelines for Managing Social Media. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gon, M. Local experiences on Instagram: Social media data as source of evidence for experience design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K. The Content Analysis Guidebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Russman, U.; Svensson, J. Studying organizations on Instagram. Information 2016, 7, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakhshi, S.; Shamma, D.; Gilbert, E. Faces engage us: Photos with faces attract more likes and comments on Instagram. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI2014), Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda, B.; Schedl, M.; Tkalcic, M. Predicting personality traits with Instagram pictures. In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Emotions and Personality in Personalized Systems (EMPIRE’15), Vienna, Austria, 16–20 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Veirman, M.; Hudders, L. Disclosing sponsored Instagram posts: The role of material connection with the brand and message-sidedness when disclosing covert advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2019, 39, 94–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, B.; Aicher, T. Exploring sport participants’ event and destination choices. J. Sport Tour. 2018, 22, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Jung, K.; Yoo, S.-C. Exploring the Power of Multimodal Features for Predicting the Popularity of Social Media Image in a Tourist Destination. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).