Abstract

The current study explored, in a sample of 219 young Italian adults (105 M; 114 F; mean age = 22.10 years; SD = 2.69; age range = 18–29), the contribution of the five psychosocial skills (Five Cs) identified by the Positive Youth Development approach (competence, confidence, character, connection, and caring) to sustainable behaviors, including pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic. and equitable actions. We performed four regression analyses, in which the Five Cs were the independent variables and pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic, and equitable behaviors were the dependent ones. Results reveal that character predicted pro-ecological and frugal behaviors, whereas competence was a significant antecedent of altruism. In addition, we found that caring predicted pro-ecological and altruistic actions while connection was a positive predictor of equity. These findings suggest that psychosocial resources could be crucial for sustainability, opening new possibilities for research and intervention in order to promote sustainable practices that could guarantee the well-being of the present and forthcoming generations. Limits and future research directions are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Human behavior represents the primary agent of the planetary crisis, which involves both environmental (e.g., climate change or loss of biodiversity) and social dimensions (e.g., economic and educational poverty, inequity, and injustice) [1,2]. In order to counter this crisis from a person-centered perspective, it has become crucial to understand individual mechanisms, skills and strengths that form the basis of practices that could mitigate the socio-environmental issues.

The present study seeks to investigate the individual antecedents of sustainability through the Positive Youth Development approach—PYD [3], a positive psychological framework referring to a wide spectrum of psychosocial skills that foster people’s positive behaviors. Specifically, we explore the involvement of the five psychosocial skills (Five Cs) identified by PYD, namely competence, confidence, character, connection, and caring, on a set of actions involved in protecting the natural and socio-cultural milieu [4]. We refer to such actions as sustainable behavior (SB).

1.1. Sustainable Behavior (SB) and Positive Youth Development (PYD)

SB represents a type of virtuous concrete behavior countering planetary problems under a person-centered perspective [5]. Although many classifications of SB exist in literature e.g., [6,7], empirical evidence supports the view that it comprises a broad range of deliberate, effective and future-oriented activities intended to benefit both people and their environment [4,8]. In line with framework of Tapia-Fonllem et al. [5], SB encompasses four main dimensions: pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic, and equitable behaviors. Whereas pro-ecological and frugal practices relate to the dimension of pro-environmentalism, altruistic and equitable actions belong to the pro-sociality dimension [4,9]. pro-ecological behaviors represent purposeful and effective actions (e.g., energy-saving, composting, and water conservation) focused on the conservation of natural resources and the preservation of the physical environment. According to Li et al. [10], pro-ecological practices relies on reduction, reuse, and recycling. Frugal behaviors represent a style of life of voluntary simplicity [11,12] based on environmentally responsible actions such as using bikes, walking instead of driving, and consuming environmentally friendly products. Altruistic behaviors refer to individual predisposition and intrinsic motivation to increase others’ well-being and benefits with little or no interest in reward or other forms of gratification [13]. According to Corral-Verdugo [14], altruistic behaviors depict one of the main factors feeding the motivation that originates and uphold actions protecting the environment and preventing its degradation [2]. Finally, equitable behaviors can be traced back to individual actions guaranteeing a fair distribution of natural resources as well as, ethnic, age, and gender equity [1,5]. According to Tapia-Fonllem et al. [12], equity encompasses intergenerational equity (future generations must have the same rights to access cultural resources and meet their needs as present generations); intra-generational equity (all members of society, including disadvantaged groups such as poor, children or disabled must have access to cultural, ecological, and economic decisions); and equity among more and less developed countries.

Even though predictors of SB seem to be well documented in literature [2], the current research aims to explore the individual dispositions to act sustainably through the lens of the PYD framework [3], an approach that has never been used in the Italian context.

The PYD perspective arose in the 1990s, stressing the strength and resilience of youth as well as the plasticity of human development [15,16]. The PYD model relies on the relational developmental system metatheory of human development [17], emphasizing mutual bidirectional relationships involving both people and their surrounding environment. Although different PYD models exist in literature (see [16] for a review), the most empirically supported is Lerner’s Five Cs model [3]. It depicts five main interacting psychological and social skills, namely competence, confidence, character, connection, and caring, mainly involved in youth positive development. Competence depicts the ability to manage complex environments and challenges in life, including social situations (e.g., working well with others for a common goal, which can include, for instance, the sustainability of the planet). Confidence represents people’s overall positive beliefs in their own abilities, including self-esteem and self-efficacy. Character involves the individual sense of justice, encompassing respect of social and cultural rules, correct behaviors, a sense of morality and integrity, as well as the knowledge of right and wrong. Connection describes people’s positive experience of social exchanges between themselves and the community. Finally, caring reflects people’s sense of empathy and closeness for others.

Given the pivotal role of these five dimensions in individual positive adaptive functioning [18], it is reasonable to hypothesize that they could avert socio-environmental issues and, as a result, contribute to promoting SB. This contribution, which in our view could involve sustainability, is known in PYD literature as the sixth C [19,20].

In this study, we specifically focused on PYD since it arranges at least three main advantages. First, the PYD framework highlights the role of potential strengths in fostering sustainability under a person-centered perspective in terms of both psychological and social resources. Second, it allows the exploration of the individual predisposition toward sustainability by a new theoretical perspective for the Italian context. Finally, given that specific educational programs can cultivate and enhance PYD attributes [21,22], they may represent a relevant tool for feeding the common sense of sustainability and engaging people in organized efforts to promote concrete sustainable actions.

1.2. Aims of the Study

The purpose of this research is to investigate, in the Italian context, the extent to which PYD attributes predict sustainable practices. Specifically, we performed four regression analyses in which the Five Cs were the predictors, whereas the four commonly accepted environmental and social dimensions of SB, namely pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic, and equitable behaviors, were the dependent variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

The sample of the current research consists of 219 participants (105 M; 114 F; mean age = 22.10 years; SD = 2.69; age range = 18–29; years of education: mean = 14.18; SD = 1.81). All participants signed their informed consent, completed the self-reported questionnaires and filled in a short demographic questionnaire via the Google Forms online platform. The a priori required sample size analysis, performed by G*Power 3.1 [23], revealed a suggested sample size of 55 participants. According to Barbaranelli [24] the parameters of the power analysis were: effect size = 0.15; significance level = 0.05 (medium magnitude); statistical power = 0.80; influencing factors = 5. All subjects were volunteers, and no one received any reward or incentive for taking part in this research. Participants completed the survey in about 15 min. The Local Ethics Committee approved this research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Measures of Sustainable Behavior

We assessed SB by four different scales adapted in Italian from Tapia-Fonllem et al.’s questionnaires [5]. The first one measures pro-ecological behaviors and consists of 16 items along a 4-point Likert Scale (0 = Never; 3 = Always), indexing actions related to saving energy, reusing, recycling, conserving water, and using environmental-friendly products (e.g., “Collects and recycles used paper”). The second scale evaluates frugal behaviors considering 10 items along a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Strongly disagree; 4 = Totally agree), which include the report of actions such as buying the strictly necessary, reusing clothes and objects (e.g., “If my car works well, I do not buy a new one, even if I have the money”). Ten items along a 4-point Likert scale (0 = Never; 3 = Always) assessed altruistic practices. This scale includes actions that involve assisting or helping others (e.g., “Provides some money to homeless”). We also evaluated equity by 7 items along a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Strongly disagree; 4 = Totally agree), indicating behavior or situations such as treating rich and poor as equals or providing equal educational opportunities for girls and boys (e.g., “Girls and boys have the same educational opportunities”). Cronbach’s α revealed that the internal consistency of the four scales ranged between 0.65 and 0.79, indicating acceptable reliability of the questionnaires [25]. The internal consistency reliability for the four scales was as follows: pro-ecological behaviors (Cronbach’s α = 0.73), frugality (Cronbach’s α = 0.67), altruism (Cronbach’s α = 0.79), and equity (Cronbach’s α = 0.65).

2.3. Measures of Positive Youth Development

We evaluated PYD by an adapted Italian version of a 34-item short form questionnaire of the Five Cs of PYD, PYD-SF [26], consisting of 34 items presented along a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all like me; 5 = Just like me). This measure records the Five Cs proposed by PYD through the following subscales: (1) competence measures the individual competence in academic, social and physical dimensions (e.g., “I am popular with others of my age”); (2) confidence records individual self-worth, positive identity, and appearance (e.g., “I am happy the way I am”); (3) character assesses individual social conscience, morality, and personal values (e.g., “I want to make the world a better place to live”); (4) caring explores the people predisposition toward empathic feelings (e.g., “When I see someone being taken advantage of, I want to help them”) and (5) connection evaluates positive relationships with family, neighborhood, school, and peers (e.g., “I am a useful and important member of my family”). We computed the average score with a higher score reflecting a higher level of positive development for each C. Cronbach’s α revealed that the internal consistency of the five PYD dimensions ranged between 0.68 and 0.86, indicating an acceptable to high reliability [25]. The internal consistency reliability was as follows: competence (Cronbach’s α = 0.67), confidence (Cronbach’s α = 0.68), character (Cronbach’s α = 0.86), caring (Cronbach’s α = 0.83), and connection (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

3. Data Analysis

For statistical analyses, we used Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 24 for Windows, performing descriptive statistics for analyzing demographic features of the sample and a bivariate correlation for preliminary analysis. In addition, we ran the regression analysis in order to examine whether the Five Cs predicted the four dimensions of SB. Specifically, we performed four separate regression analyses, in which the SB dimensions (pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic, and equitable behaviors) were the dependent variables, whereas the Five Cs (competence confidence, character, caring, and connection) were the predictors. Data screening showed that there were neither missing nor outlying data in the dataset. We evaluated the data normality by Skewness and Kurtosis, following the recommendations of Hahs-aughn and Lomax [27]. The distribution of the variables competence (Skewness = 0.13; Kurtosis = −0.48), confidence (Skewness = −0.36; Kurtosis = −0.46), character (Skewness = −0.35; Kurtosis = −0.15), caring (Skewness = −1.13; Kurtosis = 0.61), connection (Skewness = −0.53; Kurtosis = −0.04), pro-ecological behaviors (Skewness = −0.10; Kurtosis = 0.41), frugality (Skewness = −0.14; Kurtosis = −0.51), altruism (Skewness = 0.24; Kurtosis = −0.15), and equity (Skewness = −0.83; Kurtosis = 0.35) were normal, the Skewness and Kurtosis coefficient were each lower than three. We used table and figures in order to provide a clear picture of the results.

4. Results

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations and Pearson’s correlational analysis for all variables.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviation, and inter-correlations amongst all variables. ** p < 0.01 (two tailed), * p < 0.05 (two tailed). N = 219.

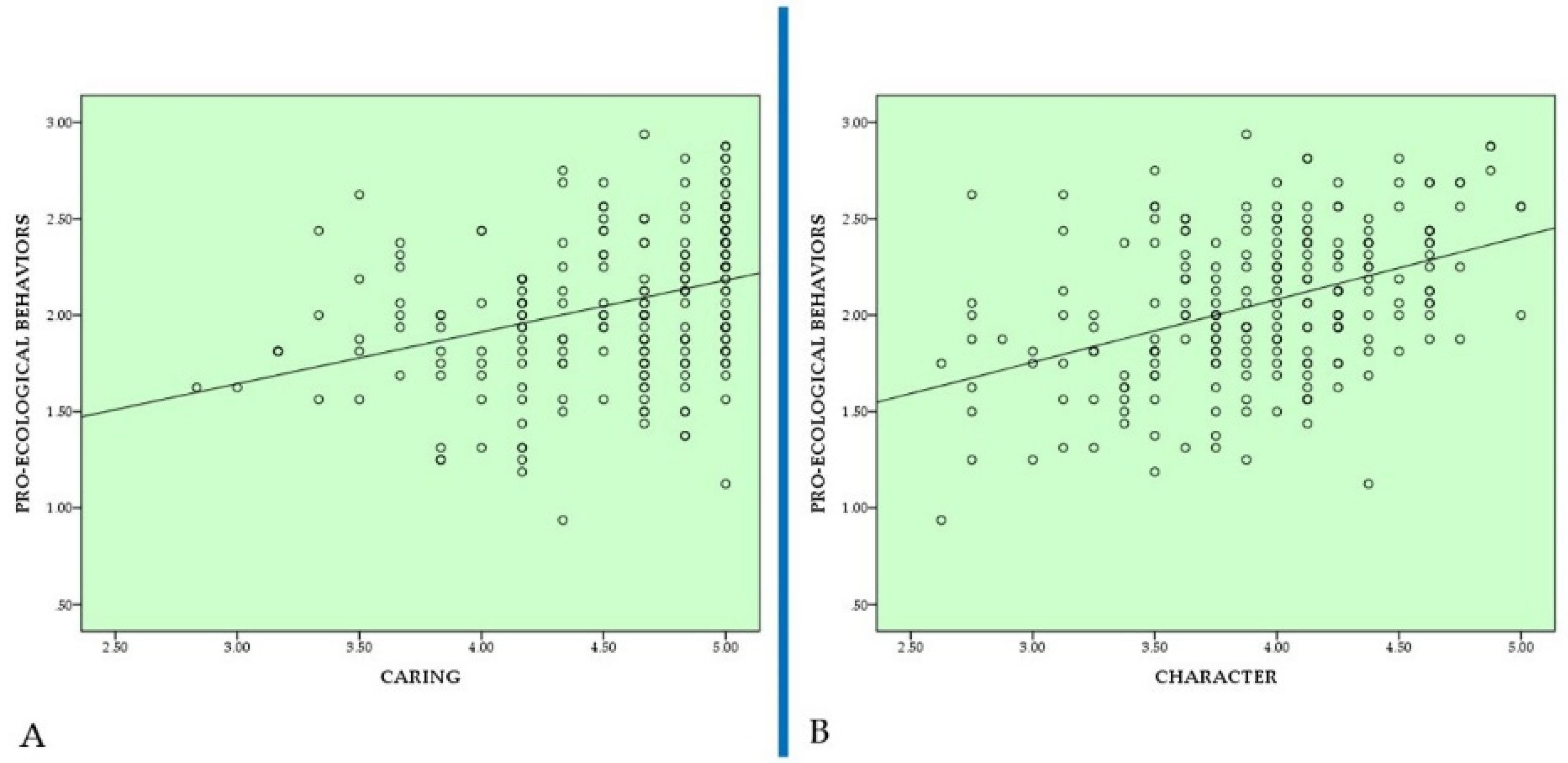

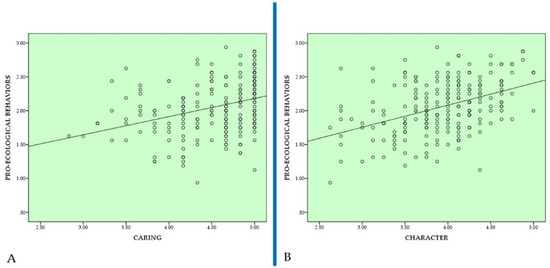

The regression analyses showed that for pro-ecological behaviors, the regression model was significant (F(5,213) = 11.67, p < 0.001) and explained 21.5 % of variance (R2 = 0.215; R2 adjusted = 0.197). The predictors character (β = 0.34, t = 4.58, p < 0.001) and caring (β = 0.14, t = 2.09, p = 0.03) were significant (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The figure shows the regression analyses evaluating the relationship between (A) caring (IV) and pro-ecological behaviors (VD); (B) character (VI) and pro-ecological behaviors (VD).

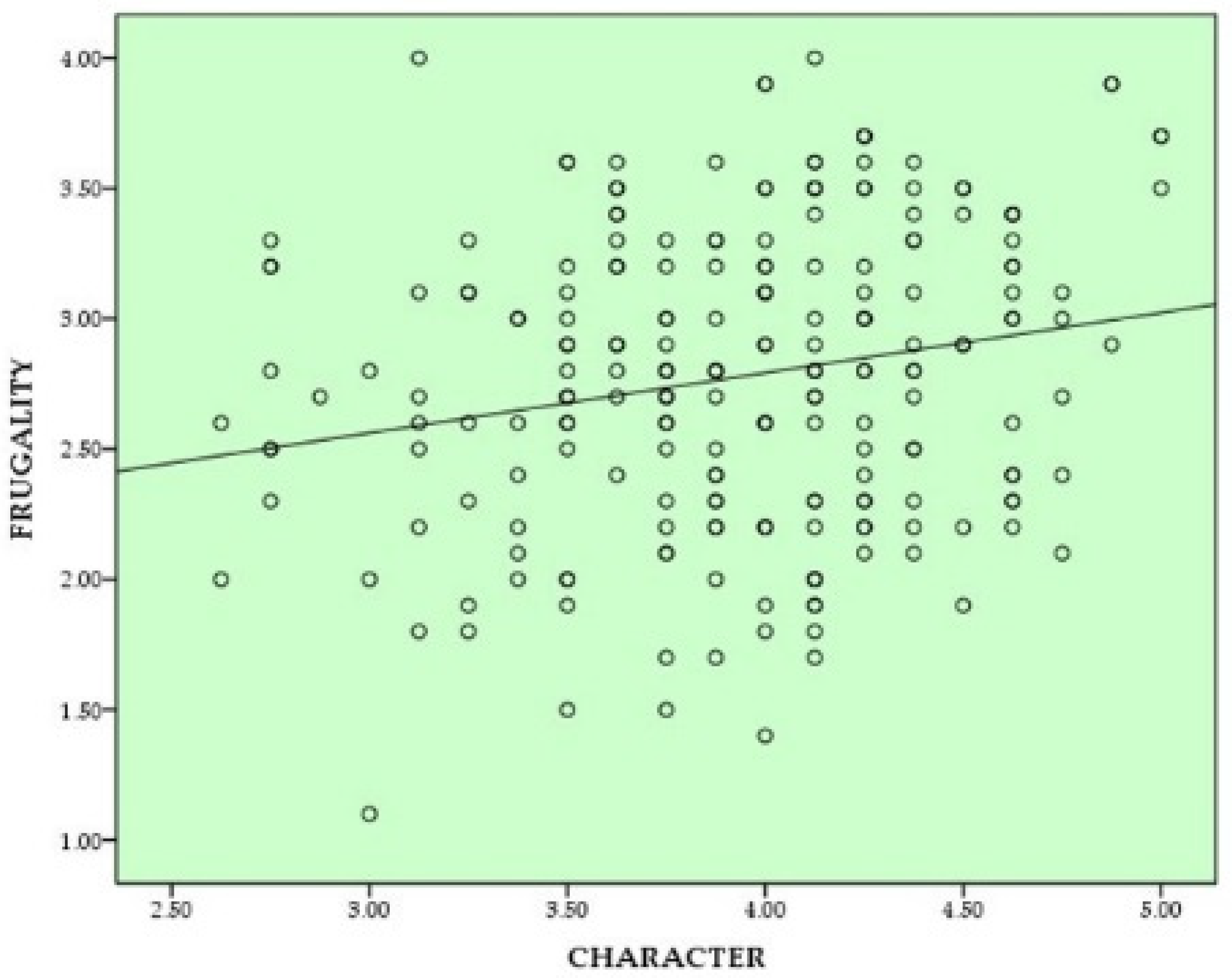

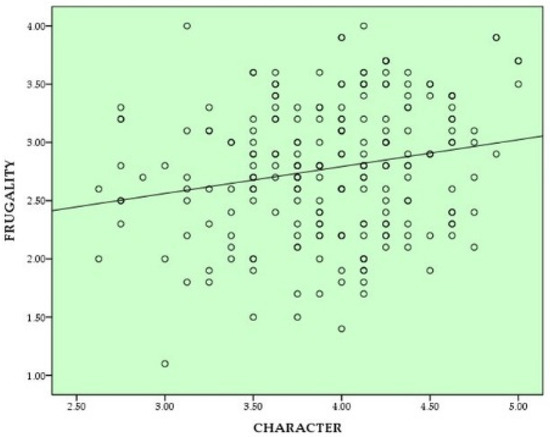

Furthermore, the regression model for frugality was significant (F(5,213) = 3.43, p = 0.005) and explained 7.5% of variance (R2 = 0.075; R2 adjusted = 0.053). In addition, character was a significant predictor of frugality (β = 0.26, t = 3.29, p = 0.001) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The figure shows the regression analysis evaluating the relationship between character (IV) and frugality (VD).

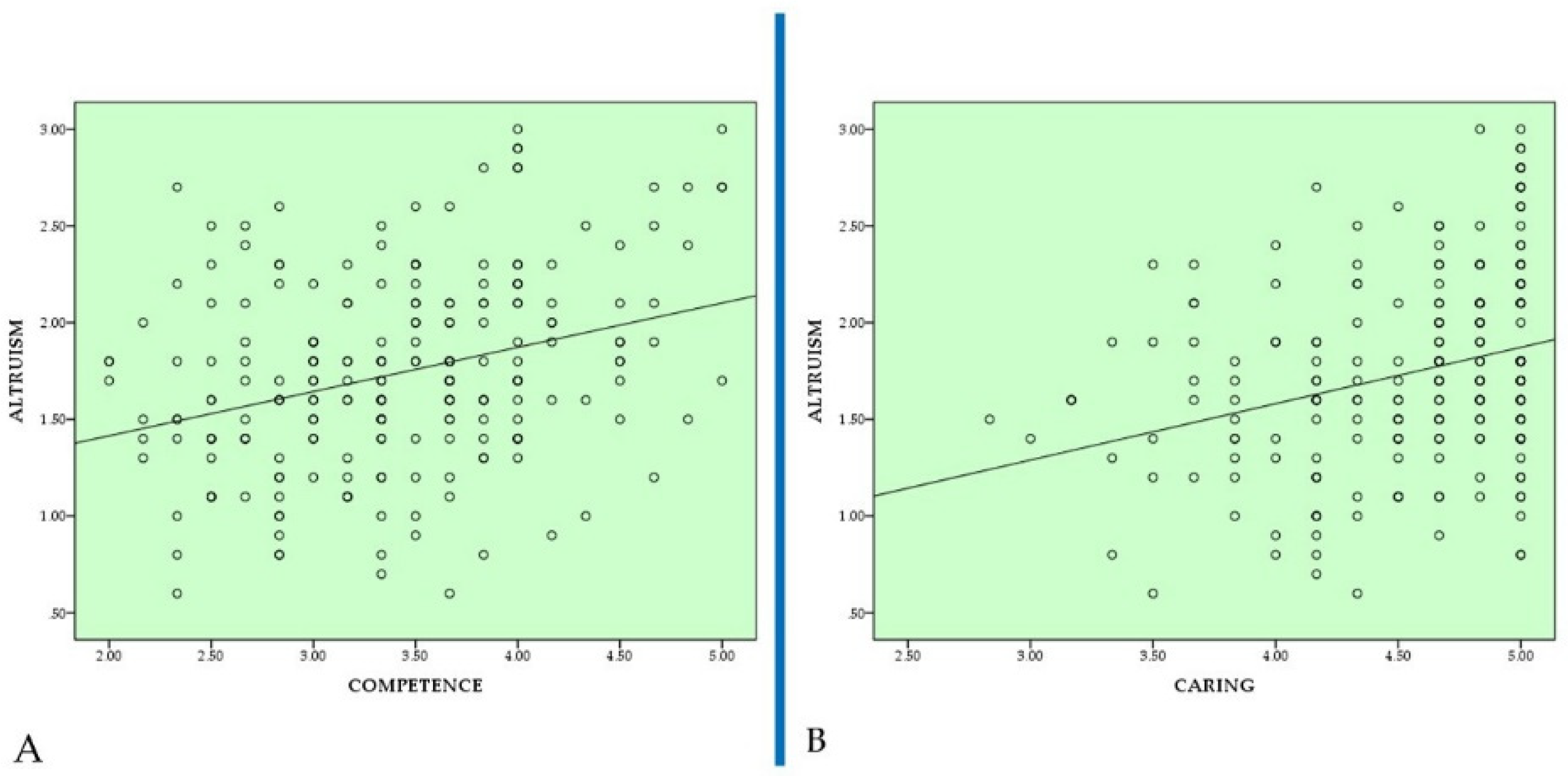

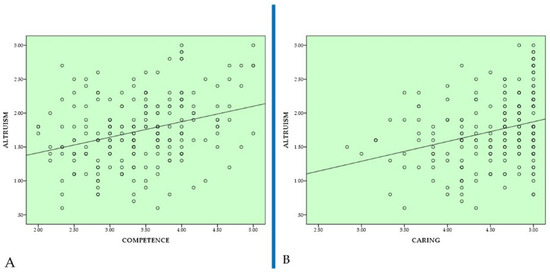

Considering altruism, analyses revealed a significant regression model (F(5,213) = 9.88, p < 0.001) and explained 18.8% of variance (R2 = 0.118; R2 adjusted = 0.169). The predictors competence (β = 0.22, t = 2.73, p = 0.007) and caring (β = 0.19, t = 2.62, p = 0.009) were significant (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The figure shows the regression analyses evaluating the relationship between (A) competence (IV) and altruism (VD); (B) caring (VI) and altruism (VD).

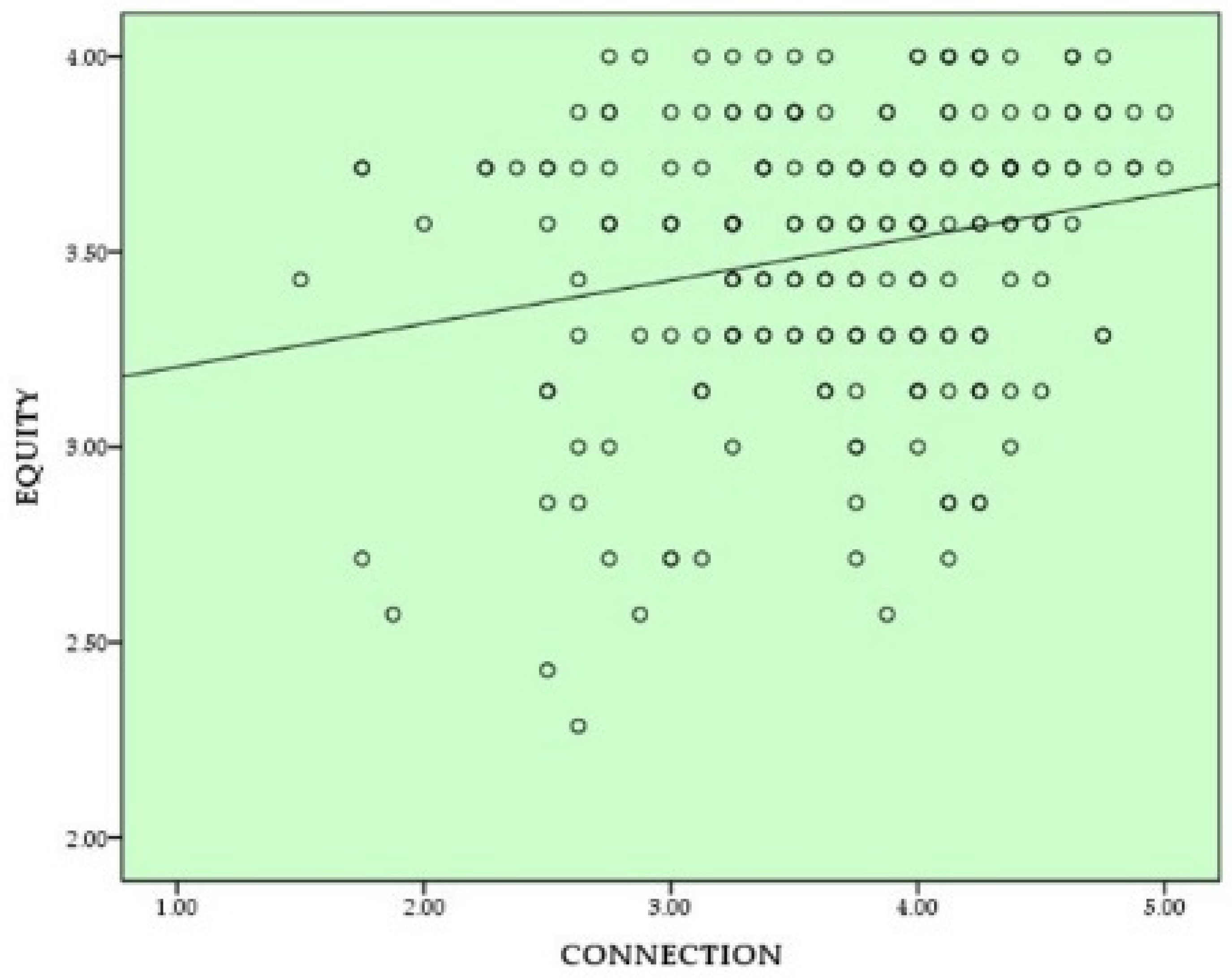

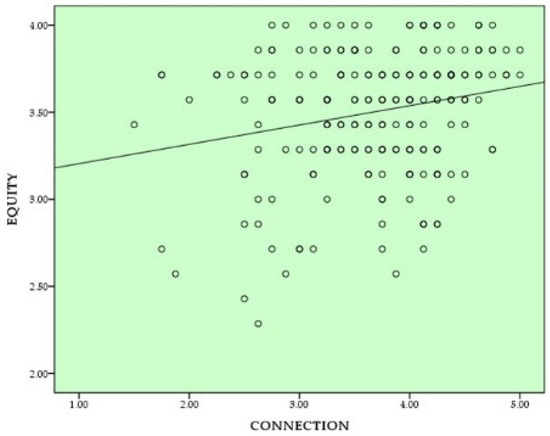

Finally, regarding equity, the regression model was significant (F(5,213) = 4.44, p = 0.001) and explained 9.4 % of variance (R2 = 0.094; R2 adjusted = 0.073). The predictor connection was significant (β = 0.22, t = 2.54, p = 0.12) (See Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The figure shows the regression analysis evaluating the relationship between connection (IV) and equity (VD).

5. Discussion

The current research aims to investigate the individual determinants of SB through the lens of the Five Cs identified by the PYD approach [3], namely competence, confidence, character, connection, and caring. According to Tapia-Fonllem et al.’s framework [5], we evaluated SB considering four behavioral dimensions: pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic, and equal actions. Results from our study reveal that character predicted pro-ecological and frugal behaviors, whereas caring predicted pro-ecological and altruistic behaviors. In addition, competence and connection were significant determinants of altruism and equity, respectively.

Regarding the predictive role of character in pro-ecological and frugal behaviors, as mentioned earlier, this PYD dimension relies on people’s sense of justice, including the respect of social and cultural rules, morality and integrity. According to the value-belief-norm theory [28], values represent the core factors of a causal chain affecting the awareness of negative consequences of behaviors as well as the ascription of personal responsibility for such consequences [29]. In line with this perspective, prior research has revealed that personal values, including justice [30], lead people to a responsible environmental lifestyle [29]. Given that, the individual sense of justice underpinned by character could represent the engine for adopting pro-ecological behaviors as well as a frugal lifestyle. In this vein, Corral-Verdugo et al.’s study [1] argued that the individual sense of justice, comprising citizenship, fairness, and forgiveness, predicted the individual disposition to behave sustainably. Besides, Reese and Jacob [30] found that different dimensions of justice (e.g., intergenerational justice and ecological justice), ethical and moral values (e.g., sense of responsibility) positively affected the individual behavioral intention to act pro-environmentally. According to the Model of Environmental Justice [31], our result suggests that indignation or anger about environmental protection deeply affects the individual willingness to act in support of the natural environment. To sum up, our data is in line with the value-belief-norm theory that the individual value of justice represents a crucial factor in promoting environmentally responsible practices and lifestyles.

Regression analyses found that caring was a significant determinant of pro-ecological and altruistic practices. Focusing on pro-ecological behaviors, Corral [32] stated that caring represents one of the main individual skills that orient people to act in sustaining the natural environment, and our results support this perspective. Note that the main component of the PYD dimension of caring is empathy. Therefore, our findings are consistent with studies addressing the association between empathy and pro-ecological practices. Specifically, it has been found that empathic feelings, including emotions of sympathy, compassion, and tenderness, play a pivotal role in motivating people to protect the surrounding natural environment as well as other forms of life [33,34]. For instance, Berenguer [35] found that people showing high levels of empathy, induced by perspective-taking, exhibited stronger pro-environmental actions, such as allocating funds for environmental protection. In addition, previous research found that empathy plays an essential role in moral reasoning about ecological dilemmas [36], also representing a pivotal element of biophilia, the innate tendency to affiliate with living things, which supports wildlife conservation [37]. Furthermore, specific sub-dimensions of empathy (e.g., environmental empathy) promote people’s motivation in ecologic conservation efforts, including protecting the ocean and marine life [38,39]. Focusing on the other facet of SB, altruism, given the empathy-based nature of caring [3], our results align with prior research addressing the association between empathy and altruism. There is a longstanding history in psychology research documenting the close association between these two constructs. Batson formulated the empathy-altruism hypothesis [40,41], which proposed that people’s empathic concern produces motivation that brings them to act altruistically. Empirical evidence supports such a hypothesis, suggesting a causal role of empathy on altruism [42]. Note that in the view of Tapia-Fonllem et al.’s framework [5], adopted in this research, altruistic behavior relies not only on cooperation practices in everyday situations such as collaborating with colleagues but also on helping actions that involve stigmatized individuals, including poor, homeless, sick and older people. Thus, our results also highlight the influence of empathy in helping vulnerable groups of people by altruistic actions, aligning with prior research [43,44,45].

We also found that competence was a significant determinant of altruism. Note that this PYD attribute relies on academic, physical and social sub-dimensions. Even though we did not disentangle competence, we could assume that the social dimensions can load more on altruism than the other two sub-dimensions, explaining the significance of our results. This would suggest that the greater the ability to manage complex social situations [3], the greater the individual disposition to act altruistically. Although we know that this assumption deserves further investigation, it is in line with a consistent number of research in developmental and social psychology stressing that social competency relates to cooperation as well as spontaneous and prompted helping behaviors [46].

Finally, the predictive role of connection on equity deserves a discussion. Although to the knowledge of the current research, no study has directly evaluated the role of connection on equity, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the greater the people’s sense of connection with their family, friends and ultimately their sense of community, the greater the individual disposition to act equitably, breaking down potential prejudices and stereotypes. This hypothesis is in line with recent studies on the association between the sense of community and prejudice. For instance, Mannarini and colleagues [47], in a sample of 603 residents of the Salento region in Italy, found that an increasing sense of community relates to a decrease in blatant and subtle prejudices. In addition, our hypothesis aligns with a PYD perspective that stresses that youths involved in positive social contexts tend to show more likely evidence of positive development and less negative outcomes [48].

It is worth noting that our research provides a new explanation of the psychosocial mechanisms underlying SB in the Italian context. However, we know that this study is not without some limitations but at the same time opens new perspectives for future research.

One limit is the sample size. Even though 219 participants satisfied the a priori power analysis parameters, future studies should involve a broader sampling, including subjects at different developmental phases in order to explore potential developmental trends. One more limitation regards self-report measures. Although such instruments are widely used to observe SB, forthcoming studies should consider the assessment of sustainable practices using more complex and valid indicators of SB. Considering the close interconnection between people and environments, we believe that a fruitful future perspective is to extend our investigation with a cross-cultural view, looking at the effect of different social contexts and geographical areas on individual resources and sustainable practices.

In conclusion, the results of the current study may be helpful for researchers to better understand the individual psychosocial strengths that could be crucial in feeding a common sense of sustainability. In addition, given that specific educational programs can promote and enhance PYD attributes, our results may represent a guide to plan interventions that might help youth and young people get closer to sustainability, consolidate the process of construction of environmental identity and connection with environmentally responsible behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G., M.C.P. and S.D.; methodology, M.G. and M.C.P.; software, M.G.; formal analysis, M.G. and M.C.P.; investigation, M.G.; resources, S.D.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G., M.C.P. and S.D.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, S.D.; project administration, S.D.; funding acquisition, S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding by the Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of L’Aquila, L’Aquila, Italy (IRB approval no. 44/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Ortiz-Valdez, A. On the relationship between character strengths and sustainable behavior. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ibarra, R.E.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.O.; Fraijo-Sing, B.S.; Nieblas Soto, N.; Poggio, L. Psychosocial predispositions towards sustainability and their relationship with environmental identity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.M. Commentary: Studying and testing the positive youth development model: A tale of two approaches. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1183–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Pato, C.; Torres-Soto, N. Testing a tridimensional model of sustainable behavior: Self-care, caring for others, and caring for the planet. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 12867–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B.; Durón-Ramos, M.F. Assessing sustainable behavior and its correlates: A measure of pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic and equitable actions. Sustainability 2013, 5, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anđić, D.; Vorkapić, S.T. Interdisciplinary approaches to sustainable development in higher education: A case study from Croatia. In Handbook of Research on Pedagogical Innovations for Sustainable Development; Thomas, K.D., Muga, H., Eds.; IGI Global: Hersey, ME, USA, 2014; pp. 67–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, F.; Wilson, M. Goal-directed conservation behavior: The specific composition of a general performance. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2004, 36, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaman, A.; Otto, S.; Vinokur, E. Toward an integrated approach to environmental and prosocial education. Sustainability 2018, 10, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenberg, N.; Miller, P.A. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychol Bull. 1987, 101, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, O. Coping style and three psychological measures associated with environmentally responsible behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2002, 30, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Corral-Verdugo, V.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Sustainable behavior and quality of life. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Fleury-Bahi, G., Pol, G., Navarro, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 173–184. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D. The Altruism Question: Toward a Social-Psychological Answer, 1st ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Montiel-Carbajal, M.M.; Sotomayor-Petterson, M.; Frías-Armenta, M.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Psychological wellbeing as correlate of sustainable behaviors. Int. J. Hisp. Psychol. 2011, 4, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J.V.; Phelps, E.; Forman, Y.; Bowers, E.P. Positive Youth Development, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Bowers, E.P.; Geldhof, G.J. Positive youth development and relational-developmental-systems. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Theory and Method; Overton, W.F., Molenaar, P.C.M., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 607–651. [Google Scholar]

- Overton, W.F. Processes, relations, and relational-developmental-systems. In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science: Theory and Method; Overton, W.F., Molenaar, P.C.M., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 9–62. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Almerigi, J.; Theokas, C.; Naudeau, S.; Gestsdottir, S.; Naudeau, S.; Jelicic, H.; Alberts, A.; Ma, L.; et al. Positive youth development, participation in com- munity youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 17–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agans, J.P.; Champine, R.B.; DeSouza, L.M.; Mueller, M.K.; Johnson, S.K.; Lerner, R.M. Activity involvement as an ecological asset: Profiles of participation and youth outcomes. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, R.M. Liberty: Thriving and Civic Engagement among America’s Youth, 1st ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, L.P.; Garst, B.A.; Bialeschki, M.D. Engaging youth in environmental sustainability: Impact of the Camp 2 Grow program. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2011, 29, 70–85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Shek, D.T.; Zhu, X. The importance of positive youth development attributes to life satisfaction and hopelessness in mainland Chinese adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 3, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, C. Analisi Dei Dati: Tecniche Multivariate per la Ricerca Psicologica e Sociale; Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto: Milano, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developi.ing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G.J.; Bowers, E.P.; Boyd, M.J.; Mueller, M.K.; Napolitano, C.M.; Schmid, K.L.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Creation of short and very short measures of the Five Cs of Positive Youth Development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2014, 24, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hahs-Vaughn, D.L.; Lomax, R.G. An Introduction to Statistical Concepts; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, R.A. It’s not (just) “the environment, stupid!” Values, motivations, and routes to engagement of people adopting lower-carbon lifestyles. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reese, G.; Jacob, L. Principles of environmental justice and pro-environmental action: A two-step process model of moral anger and responsibility to act. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 51, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Russell, Y. Individual conceptions of justice and their potential for explaining proenvironmental decision making. Soc. Justice Res. 2001, 14, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, V. A structural model of pro-environmental competency. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. J. Soc. Issue 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, M.L.; Rogers, R.W. Fear-arousing and empathy-arousing appeals to help: The pathos of persuasion. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 11, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J. The effect of empathy in proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J. The effect of empathy in environmental moral reasoning. Environ. Behav. 2008, 42, 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, O.E., Jr.; Saunders, C.D.; Bexell, S.M. Fostering empathy with wildlife: Factors affecting free-choice learning for conservation concern and behavior. In Free-Choice Learning and the Environment; Falk, J.H., Heimlich, J.E., Foutz, S., Eds.; AltaMira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.C.; Cooke, S.L. Environmental framing on Twitter: Impact of Trump’s Paris Agreement withdrawal on climate change and ocean acidification dialogue. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2018, 4, 1532375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, J.; Khalil, K.; Fyfe, C.; Young, A. Effective practices for fostering empathy towards marine life. In Exemplary Practices in Marine Science Education; Fauville, G., Payne, D.L., Marrero, M.E., Lantz-Andersson, A., Crouch, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D.; Lishner, D.A.; Stocks, E.L. The empathy-Altruism hypothesis. In The Oxford Handbook of Prosocial Behavior; Schroeder, D.A., Graziano, W.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 259–281. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D.; Batson, J.G.; Slingsby, J.K.; Harrell, K.L.; Peekna, H.M.; Todd, R.M. Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimecki, O.M.; Mayer, S.V.; Jusyte, A.; Scheeff, J.; Schönenberg, M. Empathy promotes altruistic behavior in economic interactions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, K.D. The role of empathy in the care of dementia. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 1996, 3, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, H.J.; Deane, F.P.; Hogbin, B. Changing staff attitudes and empathy for working with people with psychosis. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2002, 30, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gholamzadeh, S.; Khastavaneh, M.; Khademian, Z.; Ghadakpour, S. The effects of empathy skills training on nursing students’ empathy and attitudes toward elderly people. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, L.; Ridley-Johnson, R.; Carter, C. The supersuit: An example of structured naturalistic observation of children’s altruism. J. Gen. Psychol. 1984, 110, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T.; Talò, C.; Rochira, A. How diverse is this community? Sense of community, ethnic prejudice and perceived ethnic heterogeneity. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 27, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, S.H.; Verma, S. Commentary on cross-cultural perspectives on positive youth development with implications for intervention research. Child. Dev. 2017, 88, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).