The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Food Packaging and Consumers

Abstract

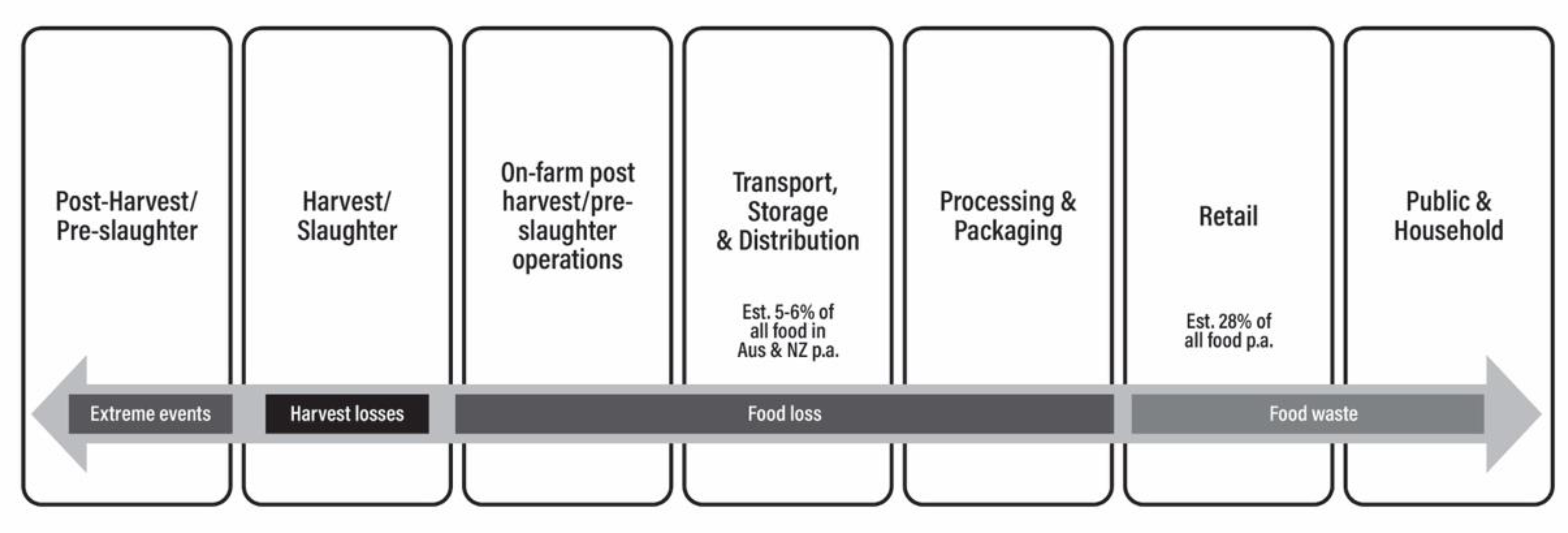

:1. Introduction

- Could packaging play a role in decreasing food waste, and if so, how much, and what sort?

- What are labelling and packaging design’s impacts on consumer decision-making about food waste?

2. Background

2.1. Packaging Perceptions

2.2. Labelling and On-Pack Information

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Journey Mapping

3.2. Pack Information Interview

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Good

Well, just because we...particularly with COVID, it’s probably better to be more cautious with the object than not...You want to know that your food’s clean and it’s not been contaminated along the way. (Female, 36–45 years old, single, living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

One [reason I am pro-packaging] is for freshness and two is the exposure to things in the air and that sort of thing. (Female, 46–55 years old, living with a family including older children at home in metropolitan Melbourne)

I would say [I am] a pro-packaging person. They do have their merits too. The convenience is one side, you can grab things and you’re not having to think to yourself before putting it in a bag, so it does have its uses. (Female, 26–35 years old, family or single parent whose children have left home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

Because it stores the food for you. I don’t know. I don’t want every fruit and veg to be packaged up. I like how they’re all singular. We’re not using plastic bags anymore, but I prefer items I buy to be in a package. I think I want the apples to be in a bag. (Female, 26–35 years old, married with children, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

I don’t want to have to get a container for every single item in my pantry. That wouldn’t be [convenient]...If I have to transfer it all myself that’d be time consuming. (Female, 26–35 years old, family with school-aged children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

It definitely leads to better quality. There’s a reason that suppliers and manufacturers are packaging them. Often it might not necessarily be for quality, it might be for ease of handling and transport, that sort of thing. Wrapping the apples in plastic means you’re not getting bugs or dust and stuff in there along the supply chain. It undoubtedly leads to a better-quality product for the consumer. (Male, 36–45 years old, family with children under five, living in regional Australia)

Well, I guess if the packaging, there’s room to write all that stuff on it or give a recipe or something like that, rather than just having to throw it out if you don’t. There’s not really that option. (Female, 46–55, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne).

4.1.1. Ease of Understanding

...that’s almost a compromise between being able to see the muffins but also being environmentally friendly compared to the six packs that are just plastic trays. The supermarket needs people to see through and think ‘well, that looks tasty and fresh, I’ll buy that’. (Female, 25–34 years old, living in a house with one other adult in metropolitan Melbourne)

It’s got the nutritional information there; it’s got the ingredients. It’s all in the one place. It’s all really easy to read. It’s got a good level of detail... I think probably key information should be on the back of the package in a really clear space that’s easy to read. (Female, 36–45 years old, single, and living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

I think it’s laid out well. The fact that it uses good fonts [easy to read]. The nutritional information is clearly laid out, and it’s got different options as far as portion sizes. One of the things I do like about the nutritional information is the percentage of recommended daily intake. (Male, 36–45 years old, single, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

It’s coloured, it’s clean, it’s simple. Yeah. I like this one. (Female 36–45 years old, single, and living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

[I like] that it’s got a clear best before date. It’s really clear on the number of servings so it’s easy to work out whether I could reasonably use it all before the best before date. (Female 36–45 years old, single, living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

4.1.2. Type of Information Communicated on Packaging

...it’s probably more the things that may be bad or may not be good for me. So, looking at things like chocolates or processed foods, and looking at some of the contents of those. (Male, 25–35 years old, married or in a de facto relationship, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

I always look at, for example, palm oil and stuff. I always check where the palm oil’s from if I’m buying a product that contains it. (Female, 18–24 years old, married or in a de facto relationship, living in Metropolitan Melbourne)

I think the actual portion themselves inside are also sealed in a bag, in a vacuum sealed bag individually, which seems like quite a waste as far as packaging goes to have this bag with a resealable portion to it...[But] it means that we generally have fish on hand in the freezer. It’s something we can stock sort of long term...These give me every confidence that they’re fine, they’re safe. (Male, 36–45 years old, family or single parent with children under five, living in regional Australia)

...if you know you can put it in the freezer then you can actually portion up the food in advance and keep parts of it in the fridge and parts of it in the freezer. (Female, 26–35 years old, married or in a de facto relationship, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

I really like the food storage conditions are up front instead and that they’re very clear...I mean, the other stuff is useful and handy but the storage conditions, I think, are the best in terms of they’re quite up front so it helps keep it front of mind. You don’t need to read through a whole group of stuff to find it. (Female, 36–45 years old, single, and living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

I do like the storage instructions... It would say, like, ‘Keep refrigerated’, ‘Open, consume within three days’, or something like that. They’re the things I remember. (Female, 18–24, married or de facto relationship, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

This actually does say after you open it, it’s giving you within five days at room temperature or refrigerated, 15 days. Then it can be frozen up to 12 months. I find that actually very useful because they give you a few options there. Then if you want to separate them, it says to microwave them, so it tells you how to cook them and then how to store them. Once open, refrigerate within three days, and you can freeze it and use it in three months. So that’s good to see also, how long it lasts in the freezer as well because then there’s going to be less wastage if you don’t use it. (Female, 46–55 years old, living with a family that includes older children at home in metropolitan Melbourne)

If you have a resealable flap that does reseal and keep the goodness of the product, that’s a bonus...if you buy 10 tacos or 10 wraps in a bag and you’re having two a day, there’s a whole week of school and if you can just pull it out and seal it up, that’s nice easy, that’s functional. (Male, no age given, family or single parent with school aged children at home, living in regional Australia).

Resealable tabs and containers work quite well for us. It means I don’t have to pull out Gladwrap or another freezer bag and use more plastic packaging kind of thing or stick it in Tupperware. It still remains in the manufacturers’ packaging which should be the optimal storage solution for it. (Male, 36–45 years old, family or single parent with children under five, living in regional Australia).

4.2. Bad

Because I’m concerned about the potential for chemicals and nasties to reach into food products. When I buy a food product from a market or a store that doesn’t let you bring your own packaging, I don’t know whether it’s just because they are having to buy it without the packaging to sell it to you. When I don’t buy it with the packaging it is better. It lasts longer. (Female, 36–45 years old, married or in a de facto relationship, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

I think I’m more concerned about the packaging waste, because even if...I have my own bedroom here, and I can collect up enough food wrappers, or soft drink cans, or this or that from just food alone within a few days. And I’m just thinking this is how much packaging I’ve thrown out just in my own bedroom. Then you have to add on other packaging from other food I’ve eaten. It’s just out of control...And plastic is a nightmare to recycle. (Female, 18–25 years old, living in a share house in metropolitan Melbourne)

Well, I think that the produce contained within, I’m thinking about specifically fruit and veggies here, it’s probably just masking inferior products, I think. If I want to buy an avocado, I want to check its firmness or ripeness, which I can’t do if it’s in packaging. So, I think that there’s a bit of smoke and mirrors going on as far as that’s concerned. (Male, 36–45 years old, single, living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

You can buy a corn on the cob with the husk all on it, or you can buy corn that’s in the thing, cut off, and there’s still some husk, but it’s in a plastic thing. Then the ends of them are starting to go pink already when you buy them sort of thing. I guess in that example, then yes, the quality has deteriorated because of the packaging, so something like that. (Female, 46–55 years old, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

…when they had basically paper packaging or cardboard packaging or metal packaging...Compared to today when everything’s in plastic. Plastic does cause a lot of food to deteriorate quicker. (Male, 56–65 years old, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne).

Sometimes it can be hard to find the date on it...Maybe just make the label yellow or have it standardised or something. Maybe it would stand out a bit more if it were one colour. (Female, 46–55 years old, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

…unless it’s vacuum sealed, I usually take it out of the packaging it was in not just because it does last longer, I also keep more fridge space, because those packages are too big. (Male, 18–24 years old, live with another adult, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

It’s the full food storage information in terms of whether it should be stored in the fridge or on the shelf or in the pantry. When the box is opened, whether you should put it in a sealed container or whether it’s okay to leave in the packaging. Once it’s opened, does that change how you need to store it? (Female, 36–45 years old, single, living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

4.3. Ugly

Because sometimes you’ll have to buy more than what you need. If something’s pre-packaged, and you need half a kilo and you can only buy a kilo, you’re going to waste half a kilo, so there’s more food waste with packaging. (Male, 56–65 years old, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

Well, if [packaging can reduce food waste] that’s true, I think I’d rather have more food waste than have more packaging. (Male, 46–55 years old, married or de facto couple, living in regional Australia).

So yeah, it’s kind of like a double-edged sword, isn’t it? Because yeah. Then you’ve got more packaging waste and less food waste. So, I don’t know which the better of two evils really. (Female, 25–35 years old, living with partner in metropolitan Melbourne)

Because you’re still going to eat it if it’s packaged or not, how it’s packaged doesn’t really affect if you’re going to actually eat the food. (Female, 26–35 years old, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

I see packaging as good for information. Personally, I wouldn’t link the packaging to help users with food waste. I just see it as a way to give information to users to what to do with the product. I wouldn’t see it as a direct correlation to stop food waste. (Male, 26–35 years old, living in share house with housemates in metropolitan Melbourne)

However, participants also stated they would like the information provided to be accurate and not overtly driven by marketing techniques. One participant expressed a high level of distrust in the information on packaging, saying that ‘there’s so much information out there, you don’t know who to believe’, but that if information about packaging reducing food waste came from the government, they might be likely to believe it (Male, 26–35 years old, living in a share house in metropolitan Melbourne).

I tend to not take huge amounts of notice of labels unless I’m looking for something in particular. If there were two options, I might look at the lower sugar option as the product. But that’s about it. (Female, 46–55 years old, family with older children at home, living in metropolitan Melbourne)

I’m a bit of a creature of habit and I pretty much just have things in storage that was on my list at the time. But if I was buying something new, I would read the packaging for sure. (Female, 46–55 years old, living with a housemate in metropolitan Melbourne)

I have learned a lot about defrosting and freezing food and safety in regard to that. No, I think I feel fairly confident. It’s not something that I will probably stop in the supermarket to look at and read. (Female, 46–55 years old, a family or single parent with school aged children at home, living in rural Victoria)

I don’t think [this label with storage instructions] would change my behaviour though, because I’m like, ‘I’ve consumed eggs for this long, and they’ve been fine’. And I don’t really like the idea of having extra packaging in my fridge. (Female, 25–35 years old, living with partner in regional Victoria).

The cling wrap will still let in some air. It’s not going to be completely airtight. So, the general rule of thumb is, chicken can be two to three days in the fridge. Meat can be three to seven. So, you just have to be mindful of what packaging you’ve got. You can even benefit from taking it off the original packaging you get and putting it in an airtight bag like a get a sandwich bag, lower it into some water and as that pushes out the air from it, seal it and then you’ve got a relatively air free bag. (Male, 18–24 years old, living in with another adult in metropolitan Melbourne).

I also have no idea what to do with foil packaging. I’m like I don’t know if it’s recycled. I don’t know if it’s something I said. I just don’t know what to do with it...Whereas everything else I can look at them work it out. (Female, 18–24 years old, living alone in metropolitan Melbourne)

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Coding Framework

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

| Bad | Bad\Date label missing | - |

| Bad\Date labelling hard to find | ||

| Bad\False sense of food safety security | ||

| Bad\Flimsy packaging | ||

| Bad\Location of production missing | ||

| Bad\Needs more storage info | ||

| Bad\No nutritional info | ||

| Bad\No packaging recyclability info | ||

| Bad\No storage information | ||

| Bad\Non-recyclable materials | ||

| Bad\Not much information | ||

| Bad\Pictures unclear | ||

| Bad\Provenance info not detailed enough | ||

| Bad\Text too small to read | ||

| Bad\Too much info | ||

| Bad\Too much packaging | ||

| Contributes to waste | - | - |

| Date labelling | Date labelling\Best before date | - |

| Date labelling\Best by date | ||

| Date labelling\Buy based on date label | ||

| Date labelling\Buy close to expiry if plan to use soon | ||

| Date labelling\Consume after best before date | ||

| Date labelling\Consume beyond expiry date | ||

| Date labelling\Date labelling adherence | ||

| Date labelling\Date labelling awareness | ||

| Date labelling\Do not buy based on date label | ||

| Date labelling\Do not consume after date if also smells bad | ||

| Date labelling\Guess at expiry | ||

| Date labelling\No date label | ||

| Date labelling\Pay close attention | ||

| Date labelling\Relationship between expiry date and intended use | ||

| Date labelling\Use by date | ||

| Developments | Developments\Both use-by and best-before on label | - |

| Developments\Colour to stand out | ||

| Developments\Coloured date labels | ||

| Developments\Combined date label and storage instructions | ||

| Developments\Environmental impact package info | ||

| Developments\Food safety info related to date labels | ||

| Developments\Freezing timing instructions | ||

| Developments\Icons and pictures | ||

| Developments\Info on back of package | ||

| Developments\Instructions about what to do with moisture absorber | ||

| Developments\Make label text larger so easier to see | ||

| Developments\More detailed storage instructions | ||

| Developments\More positive storage info | ||

| Developments\Recipe ideas | ||

| Developments\Recyclability | ||

| Developments\Recycling instructions | ||

| Developments\Reduce food waste instructions | ||

| Developments\Reheating instructions | ||

| Developments\Storage conditions | ||

| Developments\Storage in pack info | ||

| Developments\Storage info first | ||

| Developments\Storage out of pack info | ||

| Developments\Ways to extend shelf life | ||

| Food waste | Food waste\Causes of food waste | - |

| Food waste\Causes of food waste\Change of plans | ||

| Food waste\Causes of food waste\Inappropriate portion size | ||

| Food waste\Cheaper to buy new fresher product | ||

| Food waste\Composting not an option | ||

| Food waste\Disposal methods | ||

| Food waste\Disposal methods\Council food waste collection | ||

| Food waste\Disposal methods\Landfill | ||

| Food waste\Environmental reasons | ||

| Food waste\Food safety food waste relationship | ||

| Food waste\Food waste reduction methods | ||

| Food waste\Influence on food waste attitudes | ||

| Food waste\Influence on food waste attitudes\Awareness of production etc., energy | ||

| Food waste\Influence on food waste attitudes\Education on food waste | ||

| Food waste\Influence on food waste attitudes\Upbringing | ||

| Food waste\Not concerned about own food waste | ||

| Food waste\Tries to minimise food waste | ||

| Food waste\Very aware of food waste | ||

| Food waste\Waste of money | ||

| Food waste\Ways of reducing food waste | ||

| Good | Good\All info together | - |

| Good\Clear date labelling | ||

| Good\Colour used | ||

| Good\Confidence in storage methods | ||

| Good\Consumption speed info | ||

| Good\Cooking instructions | ||

| Good\Detailed | ||

| Good\Detailed storage info | ||

| Good\Detailed storage info\Useful storage information | ||

| Good\Easy to read | ||

| Good\Freezing instructions | ||

| Good\Ingredients list | ||

| Good\Key information in bold | ||

| Good\Large label | ||

| Good\Number of serves | ||

| Good\Number of servings per pack | ||

| Good\Nutritional information | ||

| Good\Packaging waste info | ||

| Good\Portion size | ||

| Good\Portions in relation to date labels | ||

| Good\Provenance (Made in Aus or elsewhere) | ||

| Good\Recycling for package instructions | ||

| Good\Refrigeration instructions | ||

| Good\Resealable | ||

| Good\Serving size | ||

| Good\Simple | ||

| Good\Website for more info | ||

| Saves food waste | ||

| Pro-packaging | Pro-packaging\Cheaper in bulk package | |

| Pro-packaging\Convenience | ||

| Pro-packaging\Habit | ||

| Pro-packaging\Hygiene | ||

| Pro-packaging\Information about food | ||

| Pro-packaging\Keeps food fresh | ||

| Pro-packaging\Keeps food fresher longer | ||

| Pro-packaging\Makes food easier to use | ||

| Pro-packaging\Pro if recyclable | ||

| Neutral feelings about packaging | - | - |

| Packaging waste disposal | Packaging waste disposal\Recycle packaging | - |

| Perceived existing knowledge | Perceived existing knowledge\Knowledgeable about food safety | - |

| Package reduces food waste awareness | Package reduces food waste awareness\Believable that package reduce food waste | - |

| Package reduces food waste awareness\Extends shelf life | ||

| Stock management | Stock management\Inappropriate portion size | - |

| Stock management\Sense test food | ||

| Stock management\Use beyond consumption recommendations on label | ||

| Ugly | Anti-packaging | Anti-packaging\Environment impact |

| Anti-packaging\Inappropriate portion size | ||

| Anti-packaging\Packaging waste | ||

| Anti-packaging\Package hides food quality | ||

| Anti-packaging\Package leaks chemicals into food | ||

| Anti-packaging\Package makes food go off quicker | ||

| Storage | Storage\Confidence in storage knowledge | |

| Storage\Do not always follow storage info | ||

| Storage\Do not read storage instructions for category | ||

| Storage\Googles storage instructions | ||

| Storage\Loosely follow storage info | ||

| Storage\Storage instructions | ||

| Storage\Storage methods | ||

| Label interactions | Label interactions\Do not look at date labels | |

| Label interactions\Do not look at label for staple products | ||

| Label interactions\Do not look at storage instructions | ||

| Label interactions\Do not usually look at label for this product | ||

| Label interactions\Look at labels for new products | ||

| Label interactions\Look for date labelling | ||

| Label interactions\Look for long shelf life | ||

| Label interactions\Look for nutrition or ingredients info | ||

| Label interactions\Looks at storage instructions |

References

- Devin, B.; Richards, C. Food waste, power, and corporate social responsibility in the Australian food supply chain. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. The State of Food and Agriculture: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L.; Langley, S.; Verghese, K.; Lockrey, S.; Ryder, M.; Francis, C.; Phan-Le, N.T.; Hill, A. The role of packaging in fighting food waste: A systematised review of consumer perceptions of packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spang, E.S.; Achmon, Y.; Donis-Gonzalez, I.; Gosliner, W.A.; Jablonski-Sheffield, M.P.; Momin, M.A.; Moreno, L.C.; Pace, S.A.; Quested, T.E.; Winans, K.S.; et al. Food Loss and Waste: Measurement, Drivers, and Solutions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 117–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, S.; Francis, C.; Ryder, M.; Brennan, L.; Verghese, K.; Lockrey, S. Consumer Perceptions of the Role of Packaging in Reducing Food Waste: Baseline Industry Report; Fight Food Waste Cooperative Research Centre. Available online: https://fightfoodwastecrc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/FFWCRC_IndustryReport_TEXT_FINAL_low-res-july2020.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Otten, J.J.; Diedrich, S.; Getts, K.; Benson, C. Commercial and anti-hunger sector views on local government strategies for helping to manage food waste. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Canto, N.R.; Grunert, K.G.; De Barcellos, M.D. Circular Food Behaviors: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockrey, S.; Verghese, K.; Danaher, J.; Newman, L.; Barichello, V. The Role of Packaging for Australian Fresh Produce. 2019. Available online: https://afccc.org.au/images/resources/afpa-report-2019-digital-book_(4).pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Licciardello, F. Packaging, blessing in disguise. Review on its diverse contribution to food sustainability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Nand, A.; Prajogo, D. Taxonomy of Antecedents of Food Waste–A Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holsteijn, F.v.; Kemna, R. Minimizing food waste by improving storage conditions in household refrigeration. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F.; Verghese, K.; Auras, R.; Olsson, A.; Williams, H.; Wever, R.; Grönman, K.; Kvalvåg Pettersen, M.; Møller, H.; Soukka, R. Packaging Strategies That Save Food: A Research Agenda for 2030. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 23, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, F.; Williams, H.; Trischler, J.; Rowe, Z. The Importance of Packaging Functions for Food Waste of Different Products in Households. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otto, S.; Strenger, M.; Maier-Nöth, A.; Schmid, M. Food packaging and sustainability–Consumer perception vs. correlated scientific facts: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INCPEN; WRAP. Key Findings Report: UK Survey 2019 on Citizens’ Attitudes & Behaviours Relating to Food Waste, Packaging and Plastic Packaging; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2019; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Barska, A.; Wyrwa, J. Consumer perception of active and intelligent food packaging. Zagadnienia Ekonomiki Rolnej 2016, 4, 134–155. [Google Scholar]

- Pennanen, K.; Focas, C.; Kumpusalo-Sanna, V.; Keskitalo-Vuokko, K.; Matullat, I.; Ellouze, M.; Pentikäinen, S.; Smolander, M.; Korhonen, V.; Ollila, M. European Consumers’ Perceptions of Time-Temperature Indicators in Food Packaging. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, K.; Lewis, H.; Lockrey, S.; Williams, H. Packaging’s Role in Minimizing Food Loss and Waste Across the Supply Chain. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2015, 28, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikström, F.; Otterbring, T.; Lfgren, M.; Gustafsson, A. Reasons for household food waste with special attention to packaging. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Porat, R.; Lichter, A.; Terry, L.A.; Harker, R.; Buzby, J. Postharvest losses of fruit and vegetables during retail and in consumers’ homes: Quantifications, causes, and means of prevention. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 139, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, N.L.; Miao, R.; Weis, C.S. When in Doubt, Throw It Out! The Complicated Decision to Consume (or Waste) Food by Date Labels. Choices 2019, 34, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W.; Williams, H.; Verghese, K.; Wever, R.; Glad, W. Tensions and Opportunities: An Activity Theory Perspective on Date and Storage Label Design through a Literature Review and Co-Creation Sessions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roe, B.E.; Phinney, D.M.; Simons, C.T.; Badiger, A.S.; Bender, K.E.; Heldman, D.R. Discard intentions are lower for milk presented in containers without date labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 66, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Phillips, A.; Shah, P. Unclarity confusion and expiration date labels in the United States: A consumer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Spiker, M.; Rice, C.; Schklair, A.; Greenberg, S.; Leib, E.B. Misunderstood food date labels and reported food discards: A survey of U.S. consumer attitudes and behaviors. Waste Manag. 2019, 86, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsome, R.; Balestrini, C.G.; Baum, M.D.; Corby, J.; Fisher, W.; Goodburn, K.; Labuza, T.P.; Prince, G.; Thesmar, H.S.; Yiannas, F. Applications and Perceptions of Date Labeling of Food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 745–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomson, G.B. Food Date Labels and Hunger in America Student Comment. Concordia Law Rev. 2017, 2, 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.L.; Miao, R.; Weis, C. Seeing Is Not Believing: Perceptions of Date Labels over Food and Attributes. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 611–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.L.; Rickard, B.J.; Saputo, R.; Ho, S.T. Food waste: The role of date labels, package size, and product category. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 55, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, M.D.; Stanley, R.A.; Eyles, A.; Ross, T. Innovative processes and technologies for modified atmosphere packaging of fresh and fresh-cut fruits and vegetables. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WRAP. Labelling Guidance: Best Practice on Food Date Labelling and Storage Advice; WRAP, Food Standards Agency and Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-07/WRAP-Food-labelling-guidance.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- Secondi, L. Expiry Dates, Consumer Behavior, and Food Waste: How Would Italian Consumers React If There Were No Longer “Best Before” Labels? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyndhurst, B. Consumer Insight: Date Labels and Storage Guidance; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2011; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L.; Fry, M.-L.; Previte, J. Strengthening social marketing research: Harnessing “insight” through ethnography. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2015, 23, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ludwig, T.; Wang, X.; Kotthaus, C.; Harhues, S.; Pipek, V. User narratives in experience design for a B2B customer journey mapping. Mensch Und Comput. 2017-Tagungsband. 2017. Available online: https://dl.gi.de/handle/20.500.12116/3263 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Temkin, B.D.; McInnes, A.; Zinser, R. Mapping The Customer Journey: Best Practices For Using An Important Customer Experience Tool; Forrester Research Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 5 February 2010; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, N.; Vermeir, I.; Slabbinck, H.; Lariviere, B.; Mauri, M.; Russo, V. A neurophysiological exploration of the dynamic nature of emotions during the customer experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B. Packaging design and development. In Packaging Technology; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 411–440. [Google Scholar]

- Lockrey, S.; Hill, A.; Langley, S.; Ryder, M.; Francis, C.; Brennan, L.; Verghese, K. Consumer Perceptions and Understanding of Packaging: Journey Mapping Insights Report; Fight Food Waste CRC: Urrbrae, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://fightfoodwastecrc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/FINAL_FFWCRC_JourneyMapping.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Millen, D.R. Rapid ethnography: Time deepening strategies for HCI field research. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, New York City, NY, USA, 17–19 August 2000; pp. 280–286. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/347642.347763 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Pink, S.; Morgan, J. Short-term ethnography: Intense routes to knowing. Symb. Interact. 2013, 36, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Victoria. Love Food Hate Waste Pre Campaign Community Research; Sustainability Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, L.; Parker, L.; Lockrey, S.; Verghese, K.; Chin, S.; Langley, S.; Hill, A.; Phan-Le, N.T.; Francis, C.; Ryder, M. The Wicked Problem of Packaging and Consumers: Innovative Approaches for Sustainability Research. In Sustainable Packaging; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 137–176. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-4609-6_6 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Srivastava, P.; Hopwood, N. A Practical Iterative Framework for Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adair, J.K.; Pastori, G. Developing qualitative coding frameworks for educational research: Immigration, education and the Children Crossing Borders project. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2011, 34, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Firth, J. Qualitative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurse Res. 2011, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thompson, B.; Toma, L.; Barnes, A.P.; Revoredo-Giha, C. The effect of date labels on willingness to consume dairy products: Implications for food waste reduction. Waste Manag. 2018, 78, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aday, M.S.; Yener, U. Assessing consumers’ adoption of active and intelligent packaging. British Food J. 2015, 117, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Wikstrm, F. Environmental impact of packaging and food losses in a life cycle perspective: A comparative analysis of five food items. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Langley, S.; Phan-Le, N.T.; Brennan, L.; Parker, L.; Jackson, M.; Francis, C.; Lockrey, S.; Verghese, K.; Alessi, N. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Food Packaging and Consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212409

Langley S, Phan-Le NT, Brennan L, Parker L, Jackson M, Francis C, Lockrey S, Verghese K, Alessi N. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Food Packaging and Consumers. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212409

Chicago/Turabian StyleLangley, Sophie, Nhat Tram Phan-Le, Linda Brennan, Lukas Parker, Michaela Jackson, Caroline Francis, Simon Lockrey, Karli Verghese, and Natalia Alessi. 2021. "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Food Packaging and Consumers" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212409

APA StyleLangley, S., Phan-Le, N. T., Brennan, L., Parker, L., Jackson, M., Francis, C., Lockrey, S., Verghese, K., & Alessi, N. (2021). The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Food Packaging and Consumers. Sustainability, 13(22), 12409. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212409