1. Introduction

Experts often discuss and dissect social heritage values without debating the methods used to describe them. The absence of scientific consensus on the process of valuing heritage continues to be a current axis of dialogue in decision-making processes about how, when and for whom we preserve our cultural heritage [

1]. The literature tends to describe heritage value by emphasising its potential to generate cohesion and identity. However, in many cases, there is little knowledge of the distinct narratives or discourses that are embedded within different communities [

2]. From our perspective, valuing heritage has two distinct aspects: it is considered a remnant of the past and resource for the future. This dichotomy has led to a range of epistemic developments that suggest a dynamic, processual, living concept of heritage. Valuing heritage implies the involvement of heterogeneous stakeholders, including experts and researchers. However, the involvement of heterogeneous social agents often leads to a potential conflict of valuation perspectives. Numerous value categories have been addressed by different experts in recent years [

3,

4,

5,

6], including the more extended meaning of “social value”; these values are as diverse as the individuals who may feel connected to them. The complex dimension of these values should be approached from a multivocal narrative perspective [

7], rather than multiplying heritage value categories. Specifically, in this article, we will focus on the social value of different kinds of heritage (wine tradition, memorials, archaeological remains), reflecting on certain methods and their scope.

Social value has a long academic tradition and theoretical development in the field of heritage studies [

8,

9,

10]. Understanding the social value of heritage from a dynamic view that includes the perspective of different social agents and in different periods offers a deeper understanding of the transformation of regions, identities and societies [

11]. However, in practice, the complexity involved in conceptualising, measuring and assessing the social value of heritage means that it continues to be a controversial topic of academic debate [

12,

13]. It is also a crucial debate in terms of sustainability due to its close relationship with a more inclusive and balanced human development in terms of identity, social justice and access to culture.

This paper aims to advance knowledge in this area by examining in depth the issue of measuring of the social value of heritage. In particular, it asks which methods are better suited to listening to and exploring the grassroots processes of valuation and protection, which are essential in promoting sustainable positions in heritage management. Through the analysis of three case studies, we set out to explore different ways to analyse heritage-society interactions, both holistically and objectively. After the progressive and more extensive assumption of heritage as a form of dissonance involving social contestation [

14,

15], the bottom-up perspectives, understood as unruly de-authorising heritage discourses promoted by alternative social actors, are seeking joint positions to gain strength against the authoritative discourse. This is not easy given their multivocal, diverse and complex character. Conversely, a sustainable way of managing this unruly heritage often requires the development of certain norms and guiding principles, as occurs in the field of the commons [

16], as well as new dynamic perspectives on values. However, these new norms and perspectives tend to lead to a normalisation and a departing simplification of social heterogeneity. This usually ends up reinforcing the positions of experts and governors, who maintain a monolithic voice, even when participatory approaches are promoted [

17]. In our view, these authorities, in turn, could be the guardians of what we would understand as advocates of traditional heritage values such as historical, aesthetic or legacy values [

18]. Indeed, in many ways, heritage value has been considered by some authors as concomitant with the emergence of the notion of value under capitalist regimes [

19].

Critical heritage studies aim to break with authorised discourses, but how this takes hold in practice is less clear. How can we activate the mechanisms of rupture with authorised heritage discourse and reduce its elitist top-down leanings? The theoretical apparatus that has defined and qualified the shifts in the configuration of these heritage values leads to the configuration of a new order associated with ungovernable, situated and unique values [

20,

21,

22]. This brand-new scenario defends the existence of more anarchic or informal discourses and encompasses the different groups and strata of society [

23,

24,

25]. As we shall explore in the next section, methods such as ethnographic approaches play a key role in building a dataset which provides us, experts, with answers to our questions, specifically: who, what and how society is participating in these heritage processes. This appears to be the path towards decolonising our knowledge [

22] and integrating it into a contextual situated knowledge [

26,

27,

28,

29] and may also slightly change the field of heritage values in a positive manner [

30,

31]. We wish to focus our contribution on methodological aspects, which have been widely addressed in the literature [

1,

32]. In this sense, our aim is to explore strategies that can help us to learn about a multivocality that opens the path to many senses of place and shared belongings [

33], thereby shaping new social values.

Our research focuses on understanding the methods that make it possible to learn about heritage values in social spaces (including materiality) from three diverse disciplinary perspectives and in three different cultural heritage scenarios, which also belong to different scales. One of the aims is to identify the ways in which the different formal and informal stakeholders dialogue about heritage values. All our cases share their location in subaltern contexts, on the peripheries of authorised heritage management discourses, and have an informal origin. This allows us to approach the issue of “social value” in a situated and critical way. For this purpose, what is intended is to record, maintain and reinforce social heterogeneity inside these processes of cultural standardisation, not only giving voice to the subaltern, because our positions are not more legitimate than others, but promoting, mediating and participating in the process as one more situated voice, when necessary. All that we can talk about and teach is what we can learn by observing and researching inside the process [

34].

For this purpose, we have selected three case studies. The first concerns the traditional wine-producing region of the Rías Baixas (Galicia, Spain). This study addresses an intangible social value dimension of heritage linked to consumption habits and local economies. Here, the methodology focuses on the role of society in the survival of tradition (and its reconstruction). In this case, the reconstruction of tradition arises from a heritage jeopardised by global economies and models of production. The second case study examines the memorial landscape of the Paris Commune of 1871, understood as a living social construction that can still be perceived. The relationships between space, memory and atemporality are analysed via the comparison of past and present uses and through the observation of different agents behind the construction of the memorial landscape of the Commune. A third case study deals with a process of transformation of a public space in an archaeological site in Barcelona (Spain).

These examples seek to illustrate situations in which resistance actions have succeeded in eroding or becoming integrated within authorised discourses, and, in turn, these authorised discourses attempt to impose themselves through strategies of normalisation and standardisation, integrating the subversive potential of subaltern discourse and practice. Our case studies expose processes in which there is a tension between different valorisation actions. Some are embedded in social practice as a subjective cultural capital, such as processes of inheritance and tradition, of collective memorialisation and of participative processes related to the appropriation of spaces. Other processes are more related to the externalisation or objectification of values, such as the typification and designation of places of origin, or heritage sanctioned by official memory. They both have real and different effects on the community and the environment in which they are reproduced and expressed, for example, regional and urban landscapes, or local environments. This confers an unequivocally political character upon research into heritage values and leads to an academic need to adopt a position in this respect. To this end, it is essential to set up methodological strategies to recognise the voices of multiple stakeholders, even of those who do not speak, which will be addressed throughout the article. This paper proceeds as follows: First, we will discuss methodological issues; then, we will address the Rías Baixas case followed by the case about the Paris Commune 1871; and lastly, we will present the case study of the Solar de la Muralla in Barcelona. Throughout these various cases, we will shed light on the articulation and transformation of heritage discourses as well as their interconnection with social values imposed by academic and administrative agents. Subsequently, we will discuss whether the methods employed allow us to better understand heritage-society interactions, and we will establish future avenues of research in this field.

3. Social Value and the Management of Wine Heritage: The Case of the Rías Baixas (Galicia, Spain)

The case study presented here analyses social value through the study of Designations (or appellations) of Origin (DOs). A DO is a legal concept sanctioned by the European Union that protects the uniqueness of agricultural products and derivatives such as wine, the specific characteristics of which are linked to their geographical origin, history, heritage and tradition [

36]. DOs are governed and managed by a Regulatory Council with the aim of defending the origin of products and the interests of local producers. The Regulatory Council is made up of vine growers, winemakers, cooperatives and agricultural unions, who make decisions on the direction of the DO and define the typicity of wines. This means that DOs are systems for the management of food heritage with socio-economic implications [

37]. However, despite supposedly guaranteeing the origin and authenticity associated with traditional production methods, there are no precise rules on the definition of what these are. Therefore, the definitions developed by the DOs should be understood as dynamic interpretations of the past in the present [

19].

In the logic of the DOs, tradition and heritage become malleable and dynamic resources and, therefore, controversial analytical categories, which are the object of disputes between different actors [

38]. Therefore, we ask, how is authenticity and tradition guaranteed and managed by a DO? Which aspects of tradition and history are guaranteed and preserved, and which are hidden and abandoned? Are all social actors taken into account in the definition of tradition in the territory? And, ultimately, what role do institutions such as DOs play in the preservation of a cultural heritage, its territory, its social and economic value and its sustainability? To answer these questions, we analyse the case of the DO Rías Baixas (

Figure 1). Data were collected through ethnographic fieldwork, including semi-structured interviews with more than 100 actors in the wine sector between 2014 and 2016, and through a compilation of statistical data from the DO Rías Baixas. This case study reveals the consequences of the invention of a tradition and its associated preservation policies on the transformation of the territory, as well as the wine production and consumption culture. The new management model created by the DO Rías Baixas has promoted the industrialisation and marketing of wine, which jeopardises its sustainability by undermining the social, cultural and economic value of the territory.

The Rías Baixas is a paradigmatic case study. Firstly, it illustrates the traditional Spanish production paradigm. Spain is traditionally a wine-producing country with the largest vineyard area in the world (966 M.ha in 2019) [

39]. However, it is the traditional producing country that consumes the least (27.8 litres per capita in 2019, compared to 56.4 in Portugal, 49.5 in France and 43 in Italy) and exports the most wine since 2014 (21.3 million hL of the 33.5 million hL produced) at the lowest price on the global wine market (1.26€/l). This figure is well below the average of historical European wine-producing countries (France 6.86€/l, Portugal 2.7€/l and Italy 2.98€/l) and of the new wine-producing countries (USA 2.37€/l, Chile 1.81/l and South Africa 1.31€/l). Secondly, most of Spain’s wine regions are located along the Mediterranean coast or on the Castilian plateau. Galicia, however, is characterised by a humid Atlantic climate that represents only 2% of the Spanish wine-growing landscape. The uniqueness of this region and its wines has gained international renown in recent years [

40].

Rías Baixas wines gained recognition in 1980 with the creation of the DO. This process entailed a paradigm shift. From a model based on self-consumption and the domestic market, Rías Baixas turned to an increase in production yields and a focus on exports. Before that time, Rías Baixas was associated with self-consumption and the

furancho system, and there were hardly any commercial wineries [

41]. The

furanchos were, and continue to be, family houses where the surplus of the annual wine yield is sold along with some local

tapas or dishes, without bottles, corks or labels, directly from the casks (

Figure 2). Once this surplus is finished, these establishments close their doors until the next harvest.

Furanchos establish a direct connection between production and consumption, avoiding distribution, marketing and intermediation channels, which are usually segmented in the global wine chains [

42].

The creation of the DO entailed a process of territorial demarcation and definition of the typicity and tradition of the local wines. This process set aside the wine-growing tradition associated with the furanchos and sought to delegitimise and move away from the traditional wines produced, generally made from direct-producer hybrids (i.e., not from vitis vinifera vines, but from the American rootstocks planted to fight against the phylloxera crisis in the late 19th century). Such a procedure was first associated with the approval of the Specific Designation Albariño in 1980, which prohibited the use of the word “Albariño” throughout Spain in any other wine not covered by the designation.

Subsequently, the Specific Designation Albariño adapted to European Union requirements, prohibiting the protection of specific grape varieties to become the current DO Rías Baixas in 1988. This was no trivial matter, since it was initially associated with a grape variety and later with the name of a zone, which was established around five areas or sub-zones demarcated on the basis of political decisions rather than purely viticultural tradition (

Figure 1). Some of these areas were chosen for their potential to create new extensive and high-yielding vineyards for new winemakers. The Albariño variety was selected in the first instance as representative of the DO, despite the enormous wealth of indigenous varieties existing in the territory, both white and red (Loureiro, Caíño, Espadeiro, Sousón, Brancellao, Pedral, Castañal, Godello, Treixadura, etc.). Therefore, the creation of the Rías Baixas DO was based on the invention of a tradition associated with a white grape variety in a territory where mainly red wine was produced. The justification for this decision is explained in the words of one interviewee:

“Why was Albariño chosen and not another variety when Galicia is a land of reds? Well, because it was a prestigious variety among the upper classes of the time. Besides, Albariño is a variety that ripens very well with high yields (...) and it was subsidised. Everyone planted Albariño (...) nowadays it has become the DO’s monoculture variety, accounting for 85% of the DO” (Technician of the Rías Baixas DO, 2016).

The recognition of this variety as a cultural reference point of the region was imposed by means of an administrative strategy. This consisted of the approval of a series of public programmes that subsidised the digging up of old vines and the renewal of vineyard surface area for more productive single-varietal Albariño plantations. These measures resulted in the transformation of the wine-growing landscape (

Figure 3).

This process of territorial transformation led to new challenges associated with the need to increase production volume and vineyard yields. A strategy of technological innovation ensued both in terms of product and process in the vineyard and winery. At the same time, investment in R&D&I was encouraged through collaborations with scientific institutions to carry out projects related to the clonal selection of Albariño varieties for commercial distribution and the development of patents for selected Albariño yeasts and bacteria producing specific aromas. In this sense, the case of the DO Rías Baixas is the opposite of other European regions, where what has been called the terroir ideology prevails [

37] (Barrey & Teil 2011). In these regions, the aim is to combine the cultural image of terroir with its real expression in the wine and in the territory in order to promote it as a tourist destination [

43]. In Rías Baixas, terroir is neither a claim nor a practice, but rather, it remains a heritage that is used as an abstraction for marketing purposes. The Rías Baixas shifted from being a region with a strong smallholding tradition, in which almost all the families made their own wine, to becoming an industrialised wine-growing territory, oriented towards adding value to the product by means of an export strategy and competing in the low-price market. This transformation led to significant economic devaluations of the production model, which was associated with social changes in this territory.

The data illustrate the transformation of the production model and the emphasis from the governance mechanisms on promoting high grape yields despite the social cost of such a commitment. Thus, the Rías Baixas DO, with 4052 hectares, allows a maximum yield of 12,500 kg/ha. These limits can be increased by up to 25% on the decision of the regulatory council depending on the vintage, which has occurred on several occasions. These high yields contrast with other territories; for example, the Rioja PDO allows a maximum of 6500 kg/Ha of grapes per hectare in white varieties. The statistics show an exponential increase in the volume of production, exports and vineyard surface area that runs parallel to a marked decrease in the number of winegrowers and wineries (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

The consequences of this process of reinventing a wine-growing tradition based on Albariño and the increase in production led to the standardisation of minimum qualities and historically low prices per bottle, reaching €3 in supermarkets. These prices are difficult to maintain in a sustainable way in a region traditionally characterised by smallholdings and low levels of production. This shift towards a quantity-based model was supported by the DO. Investment in advertising, marketing and promotion increased from 35% to 70% between 2014–2016, to the detriment of other budget items such as quality control, which decreased from 26% to 20% during the same period.

Thus, the DO became a marketing entity associated with a production model that has not promoted differentiation policies based on regional tradition, i.e., what the people who continued with the wine-growing activity valued or recognised as their heritage and tradition (the social value). In fact, the imposition and invention of a tradition has radically transformed the social values of the wine-making activity in that region, ranging from what they considered typicality in the wine, the varieties they planted, the cultivation systems, and even the economic activity itself.

The industrial production model is currently being challenged due to the need for real distinction in the market, not only based on marketing or on the cultural capital created by the DO. In fact, the Albariños that are generating the greatest economic value and social recognition are produced in the region by winemakers outside of, or expelled from, the DO. This phenomenon, common in other regions of Spain, is the result of the conflict between different interpretations of tradition, authenticity and viticultural typicity by different producers [

44]. The standard criteria for wine typicity are set by the regulatory councils of the DOs on the basis of oenological analyses of parameters such as volatile acidity or alcohol content and subjective assessments by expert tasters. Thus, wines made using traditional methods and varieties are rejected by the DO because they do not fit the typicity parameters set beforehand.

This production model, whose competitive strategy has withstood standardisation, basic quality parameters, high investment in marketing and low prices, has not managed to generate a connection between the social value of wine in the region and its modernisation based on tradition. This process causes grape prices to fall, which has repercussions for winegrowers. There is also the abandonment of old vineyards and quality autochthonous varieties, a unique production and consumption heritage, a lack of generational replacement, a tendency towards the concentration of vineyard ownership and the production of low-cost, low-quality wines, i.e., a loss of heritage, social, economic and territorial value.

In short, and in response to the research questions, the Rías Baixas DO was established with the aim of guaranteeing authenticity and tradition through a management model that enabled a sector and a territory to enter the global wine market, transforming the region’s wine sector at a certain point in time. The process involved the development of a wine industry and its large-scale technification, with large wine companies and cooperatives situated in rural areas favouring increases in production volumes, exports and the sector’s overall economic income. However, this model did not achieve its raison d’être: adding value to the wines by assuring consumers that they were buying a product of differentiated quality based on a unique tradition and promoting the continuity of traditional viticulture and winemaking in the region. Therefore, the imposition of certain aspects of tradition to the detriment of what winegrowers and small winemakers considered their viticultural and food heritage, i.e., their social value (grape varieties, growing areas, cultivation systems, wine typicity, forms of consumption, etc.), has led to a situation of loss of varietal biodiversity, diversity of producers and differentiated wines, as well as wine landscapes. This case study allows us to reflect on the consequences of the role played by institutions such as DOs when the different visions or social bonds of all territorial actors are not taken into account, i.e., the social value associated with an activity based on tradition and heritage. In this case, the process of intervention through preservation policies associated with the invention and reconstruction of a tradition has led to a process of social and economic devaluation of a unique wine-growing cultural heritage, thus threatening its sustainability.

4. The Social Value and Memorial Landscapes of the 1871 Paris Commune

Even after 150 years, the Paris Commune of 1871 remains a controversial episode in the collective memory of France. This can be illustrated by the fact that the regional government’s intention, announced in October 2020 [

45,

46], to declare the Sacré-Coeur Basilica a historical monument generated controversy from the outset [

47]. This church was built to expiate the sins of the successive revolutions that took place in France during the 19th century, particularly in its capital, and specifically the last one, the Paris Commune [

48,

49]. This brief episode ended in a bloodbath in which the uprising bourgeoisie, allied with the old aristocracy and the clergy, put an end, after 72 days, to the first proletarian government that could have been established in Europe. It was a military victory, accompanied by extensive repression, symbolised by the basilica on top of Montmartre hill, the construction of which was decided in 1873. It was consecrated in 1919 and is today the second most popular tourist attraction in Paris, with 10 million visitors a year [

46].

The real origin of this monument is not usually specified in touristic guides. Nor does the information panel installed in front of the façade mention the episode of the Commune, although most visitors do not stop to read it. (

Figure 6a,b). There are three other panels relatively close to the Sacré-Coeur, but located in even less frequented places, which mention the episode for different reasons, although the connotation is not always positive or at least neutral. For all of these reasons, we can venture that most of the visitors do not know or misunderstand the origin of the monument. Even so, there are still people who remember it: in the 2017 participatory municipal budgets, some people even proposed its demolition [

50], an idea which received a considerable amount of support from other social agents [

51].

Although in the beginning, the anti-communard remembrance (with the basilica as an inescapable reference) was victorious, throughout the 20th century and up until now in the 21st century, memorials dedicated to the vindication of the episode have filled the Parisian landscape [

52]. This has occurred at different stages, in specific sectors and under the initiative of different agents, as we have analysed in a previous article [

53] and is reflected in a chrono-cartography with more than 110 records (

Figure 7). This subaltern communard memory is alive and is manifested in the incessant building of memorials by some agents (among which the Association of Friends of the Paris Commune of 1871 (AFPC), founded by survivors and exiled during the 1880s, still stands out), in the performativity (actualisation of memory) of many of the practices, whether or not they are linked to these spaces, and in the presence of the Commune in the popular imagination, which can be seen in the frequent social outbursts that take place in the capital [

54].

Taking this historical controversy between communard and anti-communard positions into consideration, it can be stated that the memory of the episode has been progressively incorporated into the official memories of the French Republic as part of the process of consolidation and an episode of vindication of a social republic against the bourgeois republic [

52]. At that time, the Third French Republic was the longest-lasting contemporary French political regime (1870–1940) and several policies proposed during the Commune were incorporated in those long years, mostly after much conflict and many social demands. Step by step, the subaltern memory was included in the hegemonic discourse, albeit in a partial and filtered way. An example of this process of “normalisation” and “inclusion” is the declaration, in 1983, of the most symbolic place of communard memory, the

Mur des Fédérés, as a

Haut Lieu de Mémoire [

52] (p. 148). A pilgrimage commemorating the episode is held annually at this site at the end of May as a tribute to those killed for their cause, in which many organisations participate, although the AFPC has a prime role.

It is significant that the communard memory focused, for decades, on the vindication of martyrdom [

52,

55], generally in practices such as public ceremonies and tributes, and in street names and other kinds of memorials. Only in the last ten years, since 2011, as confirmed to us by a member of the AFPC, has the political legitimacy of the episode begun to be vindicated by promoting the incorporation of elected officials during the Commune to the panels that register all public offices installed in the headquarters of the twenty district mayors (mayoral plaques). This meant a qualitative change in the strategy of communard memory: now the value of this subaltern memory is not only existential, linked to the memory of the dead, nor merely agonistic, linked to those who have fallen for “our” cause (following the model of ways of remembering pointed out by Bull and Hansen) [

56]. Rather, the political value of the episode and a normalisation of its memory are vindicated, and there is a legitimation within the framework of the political development of the Republic. The Commune is recognised as one more episode of national construction (

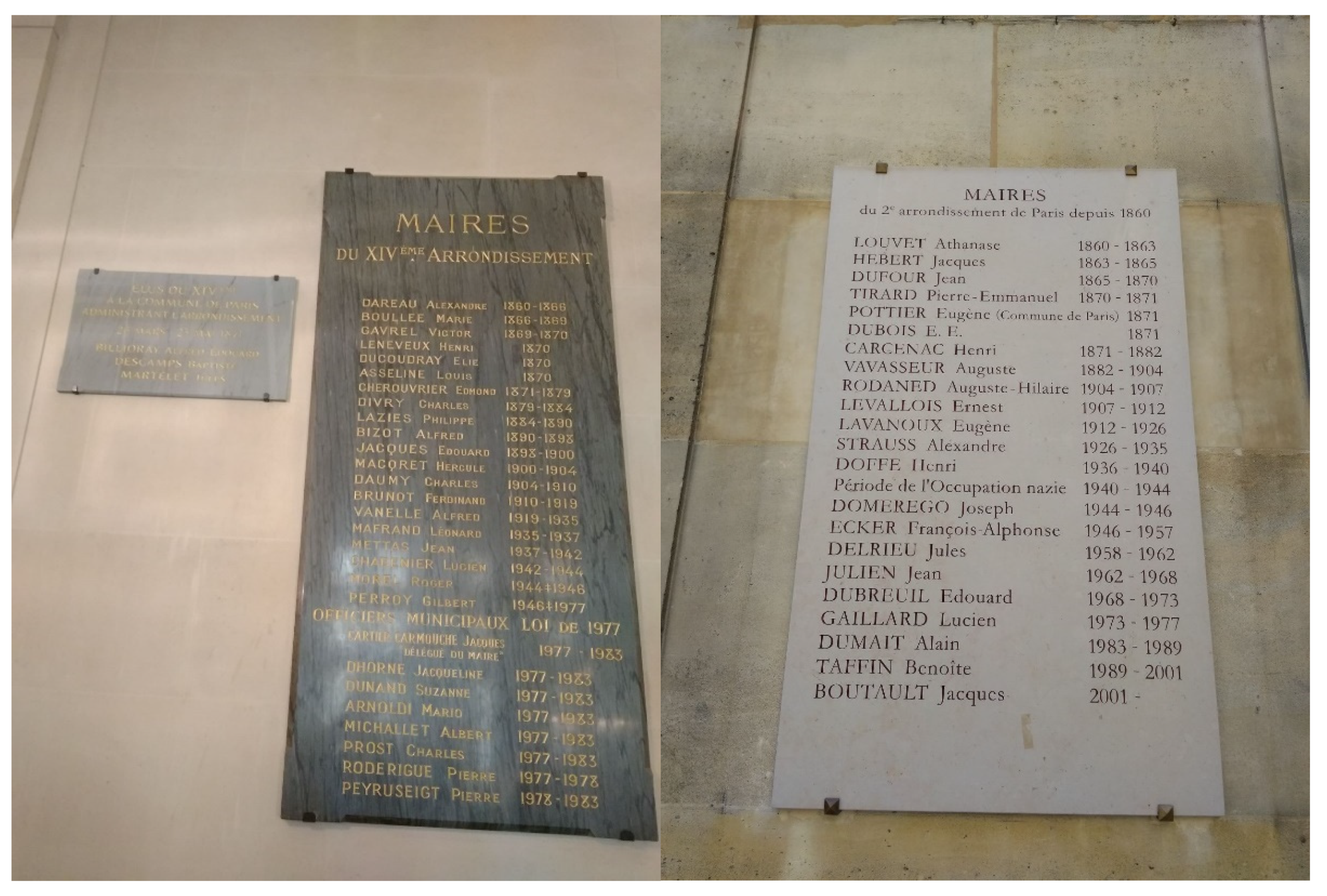

Figure 8).

This is one more step in the process of inclusion of the subaltern memory. In this way, the normalisation strategy is reoriented and consolidated, on the initiative of the same promoters of memory as always (AFPC), as a normalisation of the episode in both political and ideological terms. The question is how this legitimate aspiration is put into practice. On the one hand, it is significant which districts have agreed to install these plaques and which have not (

Figure 9), thus denoting that the ideological component continues to be controversial. Indeed, some sectors do not agree with this legitimation. On the other hand, even in those districts that have agreed to install the plaques, the way of doing so (as a separate plaque, or by renovating the old marble plaques) reveals interesting perceptual aspects, as shall be seen below. Therefore, the inclusion is not a completely satisfactory process.

It is significant that memorials and monuments are a vehicle by which memory is externalised: inscribed memory (memorials) grows and could be to the detriment of embodied memory, subjectivised in social practices, which is part of the sense of a place (

locus) and of the social identity generated in a lived space [

57] (pp. 7–39). In addition to this qualitative factor, there is a quantitative aspect: the more monuments we have, the more unlikely it is that they will be able to function as such. There is a monument congestion that can lead to inhibition, as in the case of the so-called memory boom [

58]. It can be understood that the progressive recurrent construction of a memorial landscape, even if it obeys legitimate motivations on the part of certain promoters, can generate the opposite effect: a phenomenological invisibilisation, due to saturation in terms of space and externalisation in terms of practice. This phenomenon has been well explored in an archaeological manner by Cook [

59].

This dissonance between the purpose of memorials and their real social impact is detectable in the distribution of the different types of memorials (monuments, memorial plaques, dedicated spaces, information panels) and their location, as well as in their different formats and contents (accessibility and perceptual conditions). This is despite the fact that, as one of the members of the AFPC points out, speaking of the mayoral plaques mentioned above: “What matters to us is that you can see the plaque as soon as you enter the building”. However, this is not always the case and, moreover, the issue is not the objective accessibility of the memorials, but the fact that they remain unnoticed among all the other components of the building (

Figure 10).

Thus, it could be concluded that the normalisation of collective memory ends up implying less relevance and social value (in agreement with Connerton [

57]). However, this will depend on the degree of internalization and of subjectivation of the commemorative processes in the social body. In the end, it reveals the true degree of social inclusion, understood as the social incorporation of values. Although there are monuments and memorials that denote a strategy of power to normalise a memory, to integrate it into the discourse of national construction, their use continues to be what makes the difference and what prevents their reification or conversion into an objectified value like the revaluation of the land and the aesthetics of the urban landscape rather than a subjective value, exemplified as the incorporation of the symbolic, an associative value embodied in places of memory. The constant work of the promoters to activate and perform memorial practices, whether or not they are linked to specific spaces, and the point of reference that the Commune constitutes in the social imagination, operate, temporarily, as antidotes to this process, which maintains the possibility of a more realistic inclusion as well as the capability of social agents for demanding it. These social demands grow to the extent that today’s real politics distances itself from the ideological horizon marked by the integration of communal action with republican discourse.

For instance, in 2021, 15,000 people attended the pilgrimage to the

Mur des Fédérés, the annual commemoration at the end of May, organised by more than one hundred groups (

Figure 11). It is remarkable, as we could observe during our fieldwork (in April 2018), that many people pass by the wall and look at the memorial every day (for example, 48 people passed by between 4:50 and 5:50 p.m. on Tuesday 24 April). Then, it can be said that communard memory is still alive, not only because the public commemorations are celebrated but because monuments and places still function as living

lieux de mémoire for many people. They are not meaningless or, even worse, single points to visit on a map. This is also why it can be stated that the Commune is still alive: because its values are socially incorporated, even while they are normalised and included in the official historical discourse. It is an unavoidable factor in the design of a roadmap towards sustainability in terms of the management of collective memory and the inclusion in it of subaltern memories.

5. Participation and the Social Value of Heritage: The Case of “El Solar de la Muralla” in Barcelona

This case study is focused on the process of heritagisation and the construction of a hybrid public square/school playground on a site containing important remains of a foundational Roman wall in Barcelona [

60]. Tensions between the administration and certain organised neighbourhood groups form the backdrop of this case. In 2012, archaeological works carried out in the street Sostinent Navarro resulted in the demolition of two residential buildings, causing the eviction of several residents from a neighbourhood increasingly affected by gentrification and tourism [

61,

62,

63]. This led to an interesting debate between the local residents and the administration, in which a public school came into play. The parents’ association of the school was campaigning for the use of the new site as a playground, as theirs was too small. Were the invisible remains of a Roman wall of enough value to drive out twenty neighbours?

As mentioned above, these archaeological remains are located in one of the most touristic and gentrified districts of Barcelona [

64], the so-called Gothic Quarter (henceforth, it will be referred to in its Catalan form,

Barri Gòtic). The

Barri Gòtic possesses several archaeological remains that could be placed in public spaces and others that are musealised (see

Figure 12). The study area is located in the southern part of the neighbourhood, an area with issues associated with low incomes, poor educational levels, high unemployment and the proliferation of illegal activities in houses and businesses. In addition, the emergence of tourist apartments undermines the area’s development strategies.

Public space is extremely limited in the area; the streets are narrow and many of the squares are occupied by terraces of the local bars, making it difficult to carry out any common or shared leisure activities. Thus, organised groups of residents exercise activism linked to the recuperation of spaces for housing, culture, leisure and socialisation. With the advent of participative governance [

65], the interests of these entities have an active role in current local decision-making policies. However, there is also the possibility that those in power, such as politicians or academics, may seek to reinforce their unilateral initiatives rather than finding a path towards a shared sovereignty [

66,

67]. In addition to all this, from our point of view, this active struggle only reflects the pursuit of a series of claims for rights by those who have the time to participate in their meetings and does not cover all the social classes. Unfortunately, the claims of some collectives or communities, especially those of the migrant or transient population, are not broadly represented.

The archaeological spaces of the

Gòtic could be considered significant common assets for the local community and social tissue. This

community must be considered beyond the official boundaries of the neighbourhood [

68] (p. 192), on the one hand because this place represents the past and identity of the entire city, and, on the other hand, because the activist groups for this area also come from different neighbourhoods. The members of the associations that compose the social tissue of the

Barri Gòtic have defined themselves for years as “endangered neighbours” and their organised demands, most of which are not related to heritage, have resulted in the achievement of several objectives. Thus, inhabitants face bigger issues than heritage management, especially those related with their right to use public spaces and to have access to social housing. In this regard, heritage is, to some extent, forgotten by the more organised movements of the society, although it is always available as a resource to raise awareness of social issues. Between 2015–2018, we carried out a holistic fieldwork strategy in order to understand the relationships between archaeological remains and inhabitants, attending a diverse range of events such as meetings, demonstrations, local festivals and the participative process related to the Roman walls [

69].

In this community-driven action, as in others we have analysed, in the beginning, many people initially attended meetings. Subsequently, the number decreased until only a few individuals remained in direct dialogue with the administration. Thus, which heritage values become represented at the end of the process? Those which represent the collective or those of which a minority takes ownership? For this paper, three years after the end of the fieldwork, we wanted to propose an analysis of heritage values in a retrospective perspective [

69]. Firstly, in the following sections, we wish to discuss questions related to the heritage values that come into play in these processes of reclamation, stressing how diverse communities and stakeholders can share a series of cultural significance(s). Secondly, we will explore if those values could be interwoven in multivocal discourses or narratives.

5.1. Public Use vs. Heritage Enhancement

As far as the site in question is concerned, after the demolitions in 2012, the city’s archaeological service began excavations in the surrounding area, revealing archaeological remains from different times, above all from the 18th century. The excavation work was extended until 2013. Ethnographic research showed that these actions had led to a feeling of abandonment and neglect among the local population (

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15). When interviewing neighbours, we discovered that the work carried out on the plot had generated extremely negative emotional externalities for the residents. On the one hand, they were unable to see any remains of the old Roman wall, as they were practically invisible from the fence of the excavation. On the other hand, they did not understand why these remains, which had led to the eviction of residents and the demolition of the social tissue of the neighbourhood, were not properly protected from vandalism or weather conditions. Furthermore, they did not understand why the work was progressing so slowly.

The next agent to act after the archaeological service of Barcelona was the parents’ association of the Baixeras School. This primary school had lost its playground following the Spanish Civil War, and their request was to transform this space into a new school playground (

Escola Angel Baixeras). They set up a blog (

https://vivimaqui.wordpress.com/, accessed on 8 November 2021) and began to organise different actions to raise popular awareness, including concerts, a collage and a popular

paella. For years, there had always been posters or events around the site [

69,

70]. Their message was concise: reclaim this space as a playground for the pupils, most of whom lived in a touristified area with no parks or playgrounds. In summary, the association had managed to raise awareness about how the site was neglected by the authorities and demanded a certain institutional urgency.

The last agent to join this process was the department of Urban Ecology of Barcelona’s City Council. In January 2016, they set up a participatory process hiring a company qualified in organising participatory processes (LACOL studio). No requirements were established, and any individual citizen who wanted to take part in the process was welcome. As part of our research, we became part of this process as neighbours and observers, taking advantage of this moment to carry out participant observation techniques [

60]. This experience allowed us to understand how some institutional participation channels end up becoming a “participation funnel”, in which only those citizens remain who have a cultural capital akin to the process or can dispose of more “time” to participate (better schedules). Undoubtedly, these biases can condition social value perspectives in heritage. After three participatory sessions, a follow-up committee was set up to work on the final design directly with the administration. Decisions were also made regarding the opening hours and long-term co-use of the site. The new Carme Simó square was inaugurated in September 2018, almost three years after the beginning of the participative meetings (

Figure 16).

5.2. Understanding Heritage Values in Power-Geometries

Pursuing our research, and to better understanding all the factors converging towards this space, we combined techniques such as systematic observation and unstructured and structured interviews, mostly with neighbours and shopkeepers in the quarter [

60]. Our aim was to learn about the citizens’ perception of heritage values through bottom-up processes. In addition, we also analysed the local press and attended different organised events to learn about how the general public and the social tissue interacted in top-down events organised by the City Council. These data helped us to understand which values have been present in the process of transformation and use of this space (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16). The following graph is a theoretical approximation based on the results of the fieldwork (

Figure 17). We have used recent categories of values synthesised in academic studies [

4,

30,

71], showing the values associated with the different stakeholders mapped for this case study.

To illustrate this heritage-led value-based study, we will draw on geographer Doreen Massey’s words: “the spatial, crucially, is the realm of the juxtaposition of dissonant narratives. Places and spaces, rather than being locations of distinct coherence, precisely become the foci of the meeting of the unrelated” [

25] (p. 33). The present-day square reflects the valorisation of residents’ demands and citizens’ struggles for the right to inhabit public space. Beyond a Roman past, with its aesthetic connotations, this square represents the story of a school that lost its playground and the voices of the neighbours who lost their houses because of the city council’s plan to enhance the historical value of their heritage. Ethnographic methods revealed a network of communities that, despite their cultural differences, were united against gentrification, mass tourism and monolithic decisions regarding their shared public spaces. Thus, these groups were united by common demands at a particular time and in a defined space (

El Solar de la Muralla). Stakeholders with less legitimised power, such as members of the local community and the parents’ association of the school, have been able to break with a “Roman-centric” history that the city council and the archaeological service were seeking to impose. It was through the enhancement of this Roman past that the destruction of living spaces and social relations had been legitimised by the administration. The rupture with this unique discourse had opened the way to the creation of a space to re-signify the crossed discourses, broadening the range of societies and cultures that can be brought into it [

25] (p. 29). To sum up, from our perspective, the social value of this space is indisputable. Therefore, we will not seek to categorise it: it seems to us like a transversal value with multifaceted meanings. Without the actions boosted by social demands, this space would perhaps continue to be abandoned, waiting for a timely local investment.

Regarding the situation at

El Solar de la Muralla nowadays, it is undoubtedly a space that is mostly enjoyed by schoolchildren. The square is closed at night to prevent vandalism. On the occasions that we visited the square between the years 2019 and 2021, to carry out systematic observation, we only saw one or two people using the square. Perhaps this will change as the vaccination programme progresses over the course of the year (2021) (

Figure 18). Given this new use of the square, it is most likely that its heritage values will mutate depending on the new meanings and narratives that will be generated in the present and the future. Certainly, this diagram of values, inspired by ethnographic work carried out between 2013 and 2018 (

Figure 16), would no longer be the same in the following months or years, as heritage values seem to be dynamic.

One the things that we have learned from this case study is that heritage processes are inconceivable nowadays without “empowering” community members and without endorsing a realistic (or not) idea of “progress” related to participation and shared sovereignty. The case of Barcelona shows a situation that could be repeated in other scenarios: the heritage values associated with the institutional sphere seem more intrinsic, traditional, or static. They embody an understanding of the concept of heritage as a resource/commodity rather than a social construction. This also means linking a shared or common heritage to a determined or univocal moment of history or space, diluting its role as a generator of present-day narratives. Discourses on values and power on the part of the administration do not frequently include the grassroots demands related to the heritage values attached to the most recent history of the neighbourhood, but the significance of the sites as spaces of convergence is usually highlighted to build common identities. Normally, politicians display a discourse on social value that causes an effect of authoritative and paternalistic positions. Conversely, when social agents conduct heritage value-driven management strategies, these do not only focus on such factors as the safeguarding of history or tradition but also on re-signification and finding new uses for the present. Therefore, we are of the opinion that dynamic social values, which place human interaction above aesthetics, have prevailed in the heritage discourse associated with this space.

6. Conclusions

These three case studies share an approach to heritage values in conflict, particularly “social value”. Schematically, they reflect a dispute between different values that arise in the margins from a subaltern perspective against official and/or hegemonic values. The subaltern perspective concerns various practices, memory processes and dynamics of spatial appropriation, whereas the official and hegemonic discourse offers a traditional static vision of heritage. In all cases, heritage values are equally manifested in the multiple voices that configure the social practices and in the materiality of places such as urban fabric landscapes. A reflection on the limits of our academic actions in terms of social value involves reviewing discourses issued from the research subject which do not reach the communities of interest, thus implying the carrying out of a participatory action-research phase. Moreover, it involves a dialogue between diverse disciplinary perspectives. This paves the way to establishing a methodological proposal that integrates all possible voices and, therefore, as many dimensions of value as possible. This implies inquiring about subjectivised values that are incorporated in the actor’s practice and are expressed as intentional valorisation. These are the objectified values, for instance, expressed in collective practices, in social memory, which are intangible or materialised in objects and built spaces and in the landscape in its deepest meaning. Regardless of whether we are talking about wine and furanchos, commemorative plaques and cemeteries, or public squares and Roman walls, the detailed study of this materiality and the values it can convey is essential in understanding the social reality that is constructed in relation to it.

The recognition of this complexity goes a step beyond current theories on social value that already recognise it as an emergent community value, such as those of Sîan Jones [

6,

10], confronting its essence in institutionalised values, be they historical or aesthetic. What is usually called “social value” could comprise several dimensions. Since all “value” is social, aesthetic or historical, we shall refer to “social value” regarding its capacity: (1) to generate community and association; (2) to configure links between people and things/spaces by its mere existence; and (3) to help people to identify with a political community. These could be described as associative, existential or symbolic values, but again this could seem to be a way of labelling emotions, affects or interactions with heritage. There is a complexity of values within “social value” inspired by the systematising guidelines of the Burra Charter (ICOMOS Australia 1979). To our understanding, it could be renewed towards more transversal and situational positions. Byrne et al. [

72] argue that the Burra proposal is a reifying system that focuses on singular elements and landmarks, rather than on the landscape as an integrating and holistic entity. Furthermore, they criticise the charter for parcelling out the fields of knowledge, for instance, art for architects and history for historians, a feature that hardly contributes to empowering local communities. Thus, an appropriation of patterns, objectives, and strategies of heritage conservation by communities will only occur if they are produced “from, with and for” the people [

72] (p. 11).

Learning about the social dimension of heritage values involves observing what the community or citizens do beyond what social agents and stakeholders tell us. To learn about patterns of use and behaviour and how materiality and spaces are constructed through social action, the combination of ethnographic and documentary methodologies is needed. This is essential for approaching the values that surround the participatory environment of heritage practice, in a reflective, and not merely reproductive, way. Those strategies are boosted in several international recommendations such as the Convention on the Cultural Value of Heritage (Council of Europe 2005), the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (UNESCO 2011) and the most recent Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values (ICOMOS 2014). As we have noted (in

Table 1), to understand the social dimension of heritage management, we have worked with the communities employing different techniques. The information obtained from conducting these techniques has allowed us to define our contexts in a holistic and multivocal way, considering how discourses are generated from different prisms. This multivocality endorses the voices of the actors we have identified and with whom we have been interacting. Moreover, and especially in the case of Barcelona, by carrying out fieldwork over an extended time frame, we are also mapping interactions with the temporality of the landscape. In our view, when performing these immersive community-based research paths, we could be contributing, from an academic position, towards democratising and de-elitising social heritage values.

Turning now to the issue of sustainability, which was mentioned in the introduction to the article, it can be said that, even if social value cannot be measured, a sustainable method of heritage management and its context requires a certain degree of standardisation and systematicity. This implies that our proposals should not be limited to a frame of social constructivism, understood under the form of a critical analysis of the social reality of heritage. Here, we start from a multi-faceted conception of the value dimensions at stake, even if we stick to what we commonly refer to as “social value” and assume that this is deployed in the subjective sphere (what people say, think and do) on the one hand, and in the objective sphere (what people produced and produce, and how they use it) on the other. This increases our field of analysis and, therefore, our capacity to identify conflicts and, just as importantly, to mediate them. The deeper we delve into the knowledge of social geometries and how they are articulated, the more our proposals will have a further rooting. It is worth investing time and effort in carrying out a deep ethnographic and social diagnosis because, in part, in the development of these studies could lie the success of long-term sustainable proposals. To this end, the methodological proposal is inextricably linked to the axiological component. In this sense, we suggest the generation of a stable transdisciplinary analytical framework, mainly through anthropology, geography and archaeology, which will allow for pragmatic interactions integrated into a wider idea of subalternity. Thus, the management of heritage resources needs to be guided by a more democratic perception of social values. This could also be considered a sustainable, efficient, inclusive and transformative formula in terms of identity, access to culture, socialisation and minimisation of the disintegrating effects of the neoliberal system, such as the processes of commodification, reification and exclusion of heritage.

To conclude, the purpose of this research is to contribute towards social action rather than to issue discourses that remain in the academic sphere. Research should be carried out to promote emerging processes of heritagisation, memory and innovation based on diverse identities and traditions. Processes of empowerment and democratisation contribute to a social transformation from the expert sphere, but incorporating reflexive and critical elements originating from methods and techniques makes it possible to learn about multivocal discourses and contribute towards the horizontalisation of heritagisation processes. The inherited consensual emotions, perceptions and sensations derived from individual and collective memories cannot be translated into valuing labels. We are aware that this study only provides preliminary findings. However, we hope it will help other researchers who are conducting similar investigations. It is up to us to break down the walls and labels that have been attached to social value processes concerning heritage in order to generate long-term sustainable community-driven management strategies.