Abstract

The current paper conceptualises an innovative, sustainable social business contract farming model by blending three essential business aspects, namely, relational norms, social capital, and social business dimensions. In the case of contract farming, evidence shows that the social aspect and social business-based contract farming model are over-sighted. This study offers an efficient social business contract farming model by, first, reviewing the conventional contract farming model and, secondly, by developing and proposing a robust, multidimensional model for contract farming. This proposed framework may have profound implications for the agriculture sector and may provide a strong sustainable contract farming management guideline for the global agriculture industry.

1. Introduction

Contract farming has revolutionised the agriculture sector by improving agricultural productivity in both developing and developed countries. Realising the effectiveness of contract farming, non-government organisations, policy makers, donors, and researchers have proposed to governments, especially in developing countries, to promote and facilitate contract farming to enhance agricultural productivity [1,2,3,4,5]. Contract farming is a legal agreement between a producer (grower) and a buyer (agriculture firm) for a specific duration on predefined conditions, which offers agricultural inputs and economic resources to the producer, whereas the producer, in return, allows agricultural firms to control and educate farmers about the quality and quantity of agricultural product [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Contract farming, however, is not without controversy. On one hand, contract farming offers numerous benefits to small-scale farmers, such as risk-sharing, access to higher-value markets, credit services, inputs at lower rates, reduction in transportation and marketing costs, access to technology, and access to training and technical assistance by large agricultural firms. On the other hand, despite all of the benefits, there are numerous criticisms of the negative effects of contract farming on poor farmers. [12,13]. Researchers, such as [2,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], have shed light on the drawbacks of contract farming. Researchers, including [14,15,16,21,22,23,24,25] have reported that many farmers regret participating in contract farming. Their complaints include monopolistic exploitation due to the bargaining power of buyers, unfair payment for agricultural produce, high input costs due to a constant demand for high quality, and high credit ratings.

Additionally, refs [22,23,24,25,26] have raised concerns over the written contracts, including the legal language of the formal written contracts; missing elements or relational elements, even in very well-written formal contracts; weak judicial procedure; weak contract enforcement, especially in developing countries; and the inability of small-scale poor farmers to afford legal assistance in cases of contract violation by agricultural firms, leading to small scale farmers eventually losing their autonomy [2,26,27]. Relational informal contracts have been introduced as a substitute for formal contracts to ensure trust and transparency, especially in an environment where contract enforcement by third parties (courts) is weak. The underlying relational norms in relational contracts, strengthen the value of the contract by increasing the trust in parties under contract. However, researchers are sceptical about relational contracts because of the possibility of not disclosing all the relevant information, conflict, and moral hazard due to selective interpretation of ambiguous information, distrust and opportunistic behaviour. The weak contract enforcement by a third party or complete absence of contract enforcement by a third party makes one party—mostly, the weaker party (small-scale farmer)—bear all the losses in case of contract violation by either party [27]. Therefore, it can be concluded from the above discussion that neither formal contracts nor relational contracts alone support small scale poor farmers. There is a need to apply relational norms in formal contracts to increase the trust in parties under contract. The concerns raised by researchers over informal contracts are supported by the available studies, especially those conducted in developing countries [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Debates and discussions on the pros and cons of contract farming will persist. However, the said debates are outside the scope of this work. Therefore, this study proposes a shift in the paradigm of contract farming to a more innovative and sustainable solution in order to mitigate the crisis in contract farming and to enhance the social and environmental agenda of contract farming. Sustainable innovation changes the philosophy, values, operations, and practices of the conventional business to achieve a specific purpose or realise social or environmental value beyond economic returns [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Thus, this study proposes a social business contract farming model as an innovative and sustainable solution to transform conventional contract farming.

Contract farming is associated with capitalism, which stresses maximising profit. In the process of profit maximisation, the power asymmetry between the firms and the farmers always leads the former to have an advantage over the latter. Hence, manipulation cases, as previously discussed, arise. The said challenges in contract farming can be countered by social business. Social business focuses not only on the economic aspect but also includes the social and environmental aspects [41,42,43,44]. The social business paradigm aims to support the poor by empowering them. This is a new paradigm to be advocated in contract farming. A question that arises is: “What is a conducive environment that can allow contract farming to thrive to attain the social business objectives?” A probable answer to this question is social capital.

Social capital facilitates mutually beneficial collective actions, shared representation, trust, obligation, friendship, and mutual identification. Previous studies indicate that social capital improves the farmers’ access to information, credit, and reduces the overall risk of contract farming [45,46,47]. Social capital acts as a key driver in the success of a social business or social enterprise by creating competitive advantage and by facilitating access to resources, mobilising resources, and creating formal and informal ties [48,49,50,51]. Previous studies have shown that there could be a complex mediating association among relational norms, relationship quality, and the outcome of the projects. Hence, social capital, through its dimensions, could provide the link between contract farming and social business performance.

The core of the relationship in contract farming is the relational norms. A set of relational norms has been developed by Macneil and he has stressed its importance, stating that “the behaviour that does occur in relations, must occur if relations are to continue, and hence, ought to occur so long as their continuance is valued” [46]. Hence, in improving the outcome of the contract it is important to ensure that the relational norms contribute positively towards the social business outcomes. This paper discusses how relational norms, mediated by social capital, lead to a better outcome for social business. Previous research demonstrates the importance of relational norms in protecting the relationship from opportunistic behaviour [47], as well as protecting the poor farmers from bearing all of the costs in the case of contract violation [48].

The available literature on contract farming has discussed the application of the relational contract, but no study demonstrates an integrated framework that describes how relational norms can improve the outcome of contract farming. Based on the above discussion on contract farming, social business, social capital, and relational norms, this paper provides answers to some fundamental questions. The questions and their subsequent objectives are stated below. The first question that arises from the above discussion is: what is the causal relationship of relational norms on the social business contract farming performance? The second question is: does social capital mediate the relationship between relational norms and social business contract farming performance? The first objective is to evaluate the causal relationship between relational norms on social business contract farming performance. The second objective is to examine the mediating role of social capital between relational norms and social business contract farming performance. As discussed earlier, contract farming in Malaysia—like other developing countries—has not safeguarded small-scale farmers’ welfare. Therefore, the current study will be conducted in the Malaysian agriculture sector to investigate the proposed variables.

Encapsulating the above discussion, this paper aims to propose a framework that ensures sustainable contract farming by improving contract farming performance. The current study proposes a framework that integrates relational norms, social capital, and social business performance. The proposed model will help the agriculture sector understanding the role of sustainable business practices and the importance of relational norms and social capital for achieving better contract farming performance. Furthermore, the current study will also enhance the body of knowledge of supply chain performance by reducing the communication gap between firms and farmers and strengthening the value of the relationship. The outline of the remaining paper is as follows: firstly, it discusses the theoretical basis for the development of concepts proposed in this study. Secondly, it discusses the model and proposition development. Finally, this study summarizes the theoretical and conceptual framework into an integrated framework.

2. Theoretical Foundation

The theoretical foundation of this study is provided below.

2.1. Social Business and Philosophical Assumption

Two extreme types of corporate bodies operate in the capitalist system: profit maximizing businesses with the sole purpose of value creation for shareholders, and non-profit organizations with a purpose to fulfil social objectives. In organisational structure, the new form of business called social business emerged after the Noble Prize laureate Professor Younus’s social business concept. Although Professor Younus’s Grameen Bank concept has taken 30 years to obtain recognition and appreciation worldwide, the Grameen model has strongly inspired many sectors by promoting and proposing the idea of entrepreneurialism rather than charity to counter different social issues, such as poverty [41]. Philosophically, Professor Younus’s social business concept is based on two fundamental motives of human beings: selflessness and selfishness. Selfishly, people do seek profit through business; however, social business is also based on the latter motive, philanthropic service. In other words, social business is meant to support and empower the underprivileged class of society. Social business is different from non-profit organisations as investors are allowed to take their investment back. However, there is no distribution of dividends and profit must be reinvested in the business [41,42,43,44]. Social businesses are based on seven principles. These seven principles are: objectivity, sustainability, no dividend, reinvestment of profit, gender-sensitivity and environmentally conscious, fair payment, and conducive environment and joy [41,42]. The term “social business” is used for all types of organisations, ranging from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with income-generating activities to socially responsible businesses that abide by the double or triple-bottom-line concept [42].

Many businesses, especially multinational companies in different sectors, have already adopted innovation and innovative strategies to transform their business models towards social businesses. Similarly, agricultural firms all around the world have adopted contract farming as an institutional innovation tool. Contract farming as an innovation tool has the potential to meet economic goals and improve the well-being of small-scale farmers. Thus, contract farming has the potential to transform conventional agriculture business towards social business [41,42]. A significant amount of literature in social sciences disciplines, such as economics, law and management, discusses contract farming in different aspects. The Table 1 below has summarised the contributions made by these disciplines towards contract farming.

Table 1.

Contract farming study from different aspects in different disciplines.

It is evident from the above table that the available literature in different social science disciplines has not discussed contract farming transformation towards social business. Therefore, the current paper has filled the gap in the literature by proposing a social business contract farming model that includes the social business concept, which is focused on more than just profit maximisation.

2.2. Relational Contract Theory and Relational Norms

According to [46] and other researchers on the relational contract theory, [47] developed the relational norms that have become the core or foundation of the relational contract theory and the relationship of the parties in a contract. These relational norms serve to control, guide, and regulate the behaviour of the parties under contract [47,48]. Based on years of rigorous study on the contract and Macneil relational norms, Macaulay [46] proposed ten norms or principles that can be found in any form of contract, including modern-day contracts. The ten norms are: role integrity; reciprocity; implementation of planning; effectuation of consent; contractual solidarity; the linking norms which are restitution, reliance, and expectation; creation and restraint of power; flexibility; proprietary of means; and harmonization of the social matrix [44,45,46,47].

However, these relational norms have not been operationalised by the author [46]. Subsequent researchers then developed various instruments and scales to measure the norms. They have searched for concept similarity in these 10 relational norms and have developed a scale for relational contract norms in different contexts. For instance, in 1992, 2016 and 2007, [55,56,57,58] recognised that flexibility, information exchange, and solidarity are the most commonly observed norms that have been used in different relational transaction contexts. Furthermore, [56] in 2002 refined these relational norms into five dominant norms in relational exchange. In addition, [57] in 2004 established the distinctions between common contractual and relational contract norms and proposed the significance of measuring and accessing relational norms under different scenarios [59]. Furthermore, researchers, including [50,51,52], developed and validated the scales for relational norms in the context of the construction industry [51]. However, there is no unified concept that shows the complexity of relational norms and variability of their broad connotations among different application circumstances. The agriculture sector and subsectors lack studies in a relational context. Therefore, based on past literature, this study aims to focus on four relational norms: role integrity, the propriety of the means, preservation of the relation, and harmonisation of relational conflict.

Role integrity refers to the behaviour of the parties under contract in all situations. It is expected that parties under contract in the agriculture sector will fulfil their obligation in an adequate way to overcome egoism and acting with integrity and commitment. They strive to achieve the project’s goals by minimising their tendency towards personal interest and individual goals [51,52,53,54,55]. The propriety of means refers to an expectation that the contracting parties have sufficient means to perform their duties, which shows that the relationship is directed by accepted principles. This norm in an agricultural context refers to appropriate measures, such as specified pain and gain sharing, and risk sharing to ensure the parties under contract perform their obligations fully. Preservation of the relation indicates an escalation and expansion of the norms of contractual solidarity, flexibility, restraint of power, and a certain degree of reciprocity. Preservation of the relationship involves contracting parties to select behaviour that facilitates the stability of the relationship, holds the belief that others usually rely upon, accepts combined responsibility, agrees to appraisal mechanisms, and has faith in the success of the contract [55,56,57,58,59]. Harmonisation of relational conflict refers to resolving conflicts that threaten the stability of the relationship of the contracting parties. This norm is drawn from the norm of flexibility and the harmonisation social matrix. This norm not only requires parties under contract to adhere to planning and restitution, but also to the extent to which a contracting party can cope with emergent contingencies with adaptability and flexibility [55].

Relational contracts based on relational contract theory have been practised in both developed and developing countries for many decades [46]. A relational contract based on relational theory has shown promising results in the agriculture sector in the North American continent and European countries, such as Nicaragua, America, and Germany [39,40,41,42]. The farmer participation in relational contracts in these countries has improved small scale farmers’ welfare [39,40]. However, relational contract farming in developing countries has shown mixed results. The study performed in Indonesia has shown that farmers participating in informal contracts were slightly less poor than non-participating farmers, but that farmers participating in informal contracts were vulnerable to poverty [30]. Similarly, pineapple growers in Ghana have regretted participating in informal contracts as informal agreements have not been honoured by agricultural firms. Farmers have reported that, in many cases, small scale farmers began harvesting pineapples, but the agricultural firms never returned to pick up the product, leaving farmers with unsellable products and non-payment of harvesting costs. Likewise, in India, Mozambique, and Nicaragua, relational contracts have shown relatively positive results, but farmers have reservations over welfare impact [37]. Another, study performed in the Indian state Punjab has shown that the farmers under relational contracts over-invested in fertilizers to lower their productivity and increased production costs. Farmers’ expected welfare objectives under the relational contract were not met [31]. Studies performed in India and Pakistan have shown that farmers under relational contracts have produced less than what they have produced under ideal and fully enforceable contracts [32,33]. Similarly, sweet pepper farmers in Thailand prefer marketing options without contract involvement [34]. Another study in Ghana has revealed that change in the shipping mode of pineapple from air to sea has increased production contracts and cash loans for consumption. Therefore, pineapple exporters use cash loans to increase the value of the contractual relationship, relaxing the self-enforced constraint due to the inability to enforce contracts [35]. Similarly, in Malaysia, most of the contracts between farmers and firms are informal and relational. Several studies have reported relationship issues and communication gaps between farmers and agricultural firms. Furthermore, farmers do not like to participate in contract farming due to complicated processes, ambiguous contract terms and the absence of proper contracts between farmers and the firms. In the case of written agreements, legal language is very technical for farmers, and farmers experience difficulty interpreting legal language [35,36,37]. Indeed, relational contracting is providing benefits to small scale farmers, especially in developing countries, but it does not mean relational contracts have proven beneficial for all farmers [37]. The significant amount of contract non-compliance calls for a new framework that could strengthen contract compliance, especially in developing countries.

2.3. Social Capital and Social Capital Theory

Social capital theory as an essential entry point for sustainable development has drawn the attention of the whole society, especially in rural development. Social capital theory underlies networking and social relations. The social capital theory describes how networks that are formed through social relationships generate mutual value through the exchange of resources that are valuable for collaborating parties or organizations. Several studies have considered social capital as an asset or competitive advantage for the collaborating parties or firms. The social capital theory states that social capital increases over time due to continuous exchange between collaborating parties [54]. Social capital can alleviate poverty and improve society through existing dimensions in social capital, unity, culture, custom, trust, and participation [54,55,56,57].

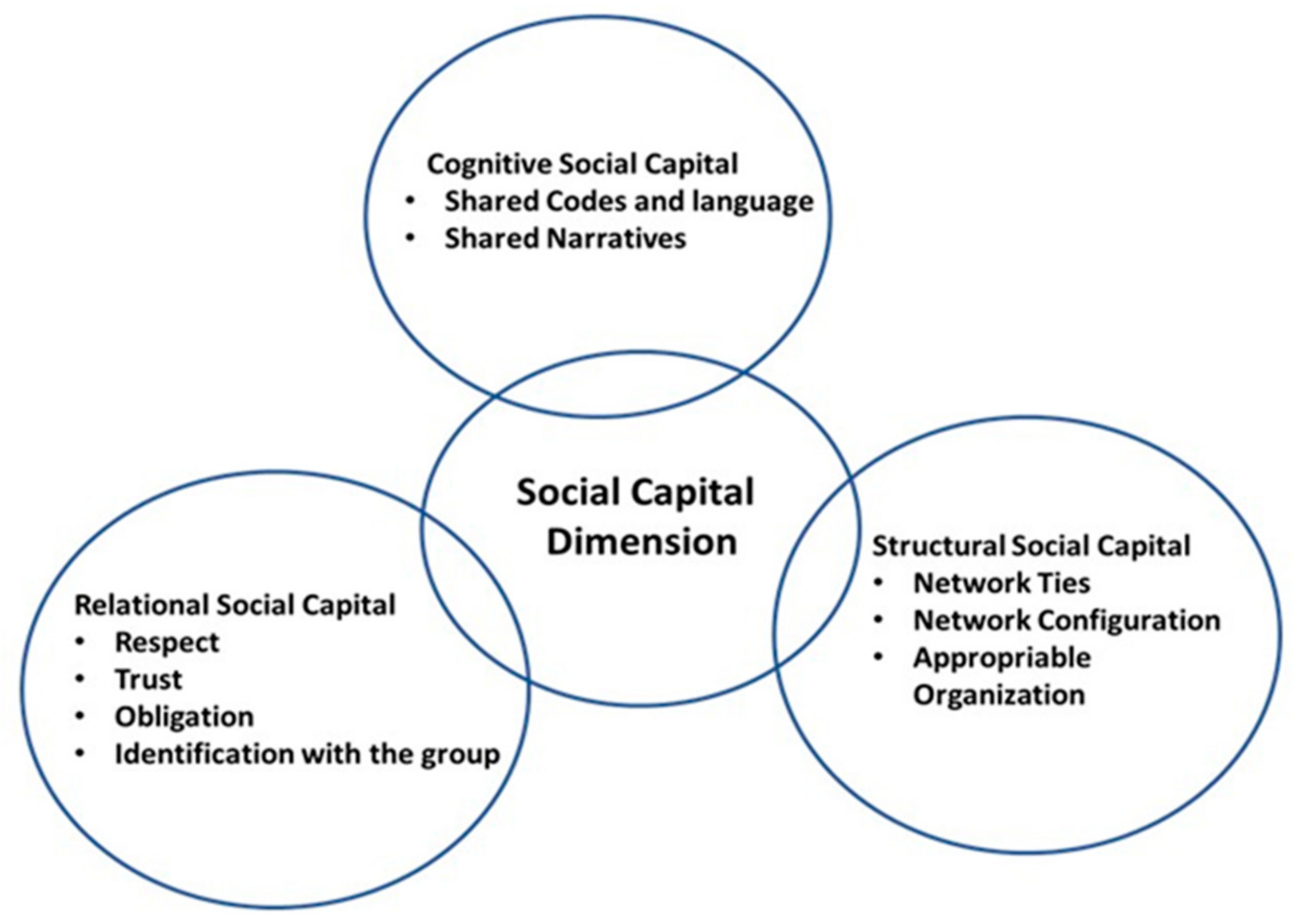

Social capital is based on three key variables: trust, social norms, and sociological aspects. In other words, social capital is a relationship and norm which forms the social relationship within the community in a broader dimension. Additionally, social capital is the capability of the people to work as a community or team to achieve mutual benefits and goals in various groups and organisations [55,56,57,58,59]. Social capital can also be defined as a set or series of shared informal values or norms, which are manifested in behaviour that propels the ability to cooperate and coordinate in producing a contribution to the sustainability of productivity [48,56,57,58,59,60]. Putnam has categorised social capital into two broader dimensions: bonding (exclusive) and bridging (inclusive). Bonding (exclusive) is a reinforcement of strong ties among close and homogenous groups, while bridging (inclusive) is based on an outlook towards weaker ties between people from different groups [59]. Theoretically, these dimensions are different but, empirically, they are inseparable, as many groups have both bonding and bridging functions [60]. Later, social capital has been categorised into three dimensions, including cognitive, structural and relational, based on a shared vision, social interactions, and trust as shown in Figure 1. The cognitive, social capital perspective is based on a shared vision which indicates that the resources provide shared representation and interpretation among parties under contract and embody the collective goals and aspirations of the members of an organisation. The relational dimension is based on trust, respect, friendship, and reciprocity, which are developed through continuous interactions. Meanwhile, the structural dimension is based on social interaction, which indicates the overall pattern of connection and interaction among the actors involved in social activities [60,61,62].

Figure 1.

Dimensions of social capital.

Social capital in the agricultural sector determines the level of productivity, as well as other forms of capital. A series of activities that cannot be performed solely by landowners or producers require cooperation among other actors in order to maintain the high quantity and quality of the product. Social capital based on cooperation makes collaboration among agriculture actors possible [63,64]. Social capital is also an important element that affects the sale of post-production agricultural products, especially in terms of manipulating the market price [65,66]. Similarly, trading activities are not possible without network availability. Social capital paves the way for the network. The role of the social capital among agriculture actors has become very much important for encouraging the bargaining positions of agricultural actors to be better. Social capital is also an essential component for agricultural actors to innovate, as making innovation in agricultural activities is more effective when carried out collectively and in collaboration [1,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. Social capital can be beneficial to the farming community by reducing transactional costs [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. Additionally, farming communities with higher social capital are better adapted to market changes and technology adoption. Poverty reduction and welfare goals can be achieved by strengthening social capital and community development. In summary, social capital has a significant role in the strategy of maintaining the sustainability of farmers’ networks in the community in order to meet their household income needs [69]. Social capital paves the way to care for the welfare of small-scale farmers by achieving economic goals. Social capital can also transform conventional contract farming towards social business. Therefore, this paper proposes a mediating role for social capital in the social business contract farming framework. Social capital can mediate social business contract farming performance and relational contract norms in a formal contract, as shown in Section 4.

3. Methodology

The current study employs a document model building approach to develop the social business contract farming model. The document model building is one of the data-driven research strategies. The documents comprises written and numerical databases [70]. Researchers in this approach search for appropriate sources and documents, make comprehensive reviews of the relevant documents, analyse them and elicit knowledge using analytical methods [71]. The data for the current study has been obtained through the systematic review process. The systematic literature review approach used in this study is well-defined and based on a specific issue or question to answer. This distinguishes the systematic literature review used in this study from traditional and narrative literature reviews. The subjects are evaluated for their significance and then summarised. Finally, a body of evidence is obtained either in favour of or against the issue or subject in question [72,73]. This approach minimises biases, gains in-depth information about the issue or subject inconsistent with the literature, identifies factors affecting the subject and issue, and creates a model of the subject by using the literature [74,75]. This approach comprises of five steps, including: clarifying the question to investigate; identifying the sources in the literature; assessing the identified sources; reviewing the sources and extracting the intended data from them; and interpreting, composing and presenting the data in a suitable form [73,74,75,76].

Considering social business, contract farming, and social capital as the main themes of the study and based on the above-stated procedure, this study has searched for keywords, such as relational contracts, formal contracts, relational norms, and agriculture farming in different databases, including Elsevier, Wiley Online Library, Emerald, etc. This paper has focused on scientific and academic papers and conferences. This paper has included the 62 most relevant scientific and conference papers written in the English language. After reviewing all of the papers, the current paper has grouped papers into the following categories, including constraints in contract farming, social capital in contract governance, and social business and social capital. The available literature has shown that no study has discussed the relationship between relational norms and social business contract farming. Therefore, this study has developed a theoretical framework to fill the gaps in the literature. Section 4 discusses the proposition and conceptual framework developed based on the literature review.

4. Conceptual Framework and Proposition Development

4.1. Relational Norms and the Value of the Relationship

The value of the contractual relationship is defined by the terms of the ongoing contract. The value of the relationship determines the future status of the contract. If the value of the relationship is high, the chance of contract violation is low, especially in the case of relational contracts [55,56]. The value of the relationship plays a key role in countries with weak contract enforcement. Furthermore, the value of the relationship saves the third-party contract enforcement cost. In other words, contract self-enforcement positively relates to the value of the relationship [55,56,57,58,59,60]. If the relationship is well established, the continuation rate of the contract is high due to the high value of the contract relationship, especially in the relational contract. The relational contracts are governed by the relational contract theory. The relational contract theory is based on relational norms, which play a major role in determining the value of the relationship [55,61,62]. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the role of relational norms in formal contracts to understand the relationship between relational norms and the value of the relationship in social business contract farming performance. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P1a):

There is a positive relationship between relational norms and the value of relationships in a formal contract.

4.2. Relational Norms and Economic Goals

Formal contracts cannot counter opportunism due to their incompleteness. Relational perspectives governed by relational norms safeguard against opportunism and encourage risk-sharing among parties under contract. The relational norms create value for all of the exchange partners. The parties that are under contract benefit from a relational perspective in all circumstances. The literature shows that the presence of relational governance in formal contracts increases the profitability of the parties under contract [66,67]. Additionally, the literature shows a positive relationship between relational governance and the profit of the parties under contract. Therefore, this paper proposes that:

Proposition (P1b):

There is a positive relationship between relational norms and the economic goal achievement of the parties under a formal contract.

4.3. Relational Norms and Farmer Welfare

Small-scale farmers’ welfare under relational contracts has shown inconsistent results. The literature on contract farming has shown that small-scale farmers’ asset portfolio has increased under relational contracts, but farmers have shown reluctance to participate in contract farming. Further, the literature has shown that small-scale farmers who participate in the relational contract are slightly less poor than farmers who have participated under the relational contract. However, small-scale farmers participating in contract farming are vulnerable to poverty [42]. Incomplete relational contracts based on relational norms have incomplete information, such as the price of the product, and the quality and quantity of the product [11]. There is a need for formal contracts due to the incompleteness and ambiguity in the relational contract. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P1c):

There is a positive relationship between relational norms and farmers welfare under a formal contract.

4.4. Social Capital and Relational Norms

Social relationships are formed through a social exchange which forms social capital [56]. According to the available literature, social capital is defined as a network of relationships that adds value to the actors by allowing them access to network embedded resources [56,57,58,59]. Similarly, the pattern of relationships and linkages formed through social exchanges form the basis for social capital [56,57,58,59]. The cognitive dimension of social capital implies sharing representations, interpretations, and systems of meaning among parties [66], which can be associated with resource sharing [55,56,57,58,59]. Cognitive social capital refers to the feelings of the people, while structural social capital relates to the behaviour of the people [55,56,57,58]. The third dimension of social capital, relational social capital, consists of the relationships partners form with each other via trust, friendship, obligation, and mutual identification. Relational social capital originates from the relational exchange, and seeking a better social exchange, which has been regulated by relational norms, serves to maintain long-term reciprocal relationships [55]. Therefore, social capital can be considered as a product of social exchange, while relational contract norms act as a set of principles to facilitate this exchange process. Thus, it can be concluded that social exchanges which abide by relational norms are more beneficial to the accumulation and generation of social capital. Precisely, an organisation with a set of goodwill-based norms is more prone to form a shared vision (the cognitive dimension of social capital) [55,56,57,58]. Likewise, the relational norms of “role integrity” and “preservation of the relation,” requires parties under the contract to have a deep understanding of the mechanism to safeguard the relationship and contribute to compatible goals [55,56,57,58,59]. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P2a):

Relational norms positively affect the shared vision of the parties under formal contracts.

Structural social capital and relational contract norms establish a series of procedures to enhance social interaction which makes network ties more concrete irrespective of frequency and quality [55,56,57,58,59]. Thus, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P2b):

Relational norms positively affect the social interactions among parties under a formal contract.

For relational social capital, trust has a positive relationship with the concepts derived from relational contract theory, including solidarity, mutuality and flexibility [55,56,57,58,59,60]. The relational norm “role of integrity” requires parties under contract to fulfil their obligations and overcome egoism, which establishes the initial trust among the parties under contract. Furthermore, the norm of “preservation of the relation” motivates the parties under contract to opt for behaviour which fosters trust by sharing responsibility. The symbiotic relationship exists between relational norms and trust [55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P2c):

Relational norms positively affect the trust of the parties under a formal contract.

4.5. Social Capital and Economic Goals

Initially, the transition of the agricultural sector from centrally planned to a market economy has failed to generate expected results. The low level of social capital has been identified as one of the factors that generates disappointing results in terms of the transformation process. Even after decades of transition, a low level of national income of countries is linked to a low level of social capital. It is claimed that farmers and farm managers have to regain and relearn how to cooperate in all transition countries. Social capital build-up establishes new relations which help to overcome market uncertainties. Past literature has shown that social capital influences gross income in the agriculture sector. Additionally, social capital plays a vital role in economic development by improving agricultural performance in developing countries. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P3a):

Social capital positively affects the achievement of the economic goals under formal contracts.

4.6. Social Capital and Welfare

With today’s rapid economic development, traditional elements of production, such as labour, land, physical capital, and entrepreneurship, can no longer adequately explain economic outcomes. The concept of social capital is receiving increasing attention when it comes to inspecting the welfare of households and the nation. Social capital has been considered as the capital of the poor and is recognised as one of the factors that can enhance farmers’ wellbeing and the rural development process in China. The available literature on social capital and households has shown that high social capital leads to higher household welfare [77,78]. Furthermore, the acquisition of social capital has a positive impact on household welfare. Additionally, the impact of social capital on household welfare is higher than other physical capital and human capital. Social capital is also an important tool to promote economic welfare. Farmers’ household welfare has been greatly improved by social capital and poor farmers are more dependent on social capital in comparison to rich farmers. Similarly, the poor’s return on social capital is larger than other forms of capital [79,80,81,82]. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P3b):

Social capital positively affects poor farmers’ welfare under formal contracts.

4.7. Social Capital and Value of the Relationship

Social capital is considered to be a collective asset that increases the efficiency of the general society in the exchange of resources that occur in it. Social capital is recognised as a resource that is obtained through the network and social relationship with the outside and the acquisition of social capital improves the economy by facilitating cooperation for mutual benefits of members of society. Social capital promotes certain behaviours in transactors in the social structure which encourage adjustments and cooperation among members of the society. Social capital is considered as one of the key tools to form information collection and knowledge bases by maintaining a sustainable relationship and network through individuals or an organisation [77,78,79]. Within an organisation, a continuous relationship as a competitive advantage is obtained through valuable, unusual, incompletely replicable and irreplaceable resources and learning effects. The ownership of intangible resources, such as social capital and effective distribution of these resources form the unique strength of any organisation. Social capital as an intangible resource is considered a mandatory approach to achieve continuous relationships and to maintain competitive advantage. Furthermore, relationship assets as a competitive advantage of organisations are acquired through cooperation between organisations [53,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Furthermore, increased transactions among organisations in a long-term relationship will increase the relationship and the competitive advantage of the organisations [77,78,79,80,81,82]. Therefore, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P3c):

Social capital positively affects the value of the relationship in formal contracts.

4.8. The Mediating Effect of Social Capital

The parties under contract work to jointly solve issues or achieve a common goal by knowledge sharing, learning and building consensus based on trust, a shared vision, and open communication [58]. According to past literature, social capital facilitates information exchange to enhance knowledge creation and knowledge sharing. The accumulation of social capital aids the cognitive and behavioural changes necessary for the adoption of a new approach [66,67]. Additionally, previous literature shows that relational governance and social capital create trust, enhance performance, and strengthen the contractual relationship. Therefore, it can be inferred that shared vision may enhance the value of the relationship. Combined with P1a, P2a, and P3c, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P4a):

The value of the relationship in formal contracts strengthens due to the effect of relational norms when mediated by a shared vision.

Communication among parties under contract plays a vital role in the successful implementation of the contract. In other words, social interactions may facilitate collective practices and create an atmosphere that is mutually beneficial for contract participants. Parties under contract are willing to share knowledge. Furthermore, relational governance and social capital, enhance the financial performance of the parties under contract. Therefore, by combining P1b, P2b, and P3a, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P4b):

The economic goal in formal contracts strengthens due to the effect of relational norms when mediated by social interaction.

Trust is one of the most critical factors influencing resource exchange and teamwork. Trust increases the willingness of parties to take part in contract farming. Trust in a relational contract increases farmers’ welfare. Moreover, social capital acts as a mediator to increase farmers’ welfare by persuading small-scale farmers to participate in contract farming. Therefore, by combing P1c, P2c, P3b, it can be proposed that:

Proposition (P4c):

Relational contract norms in the formal contract when mediated by social trust ensure small-scale farmers’ welfare.

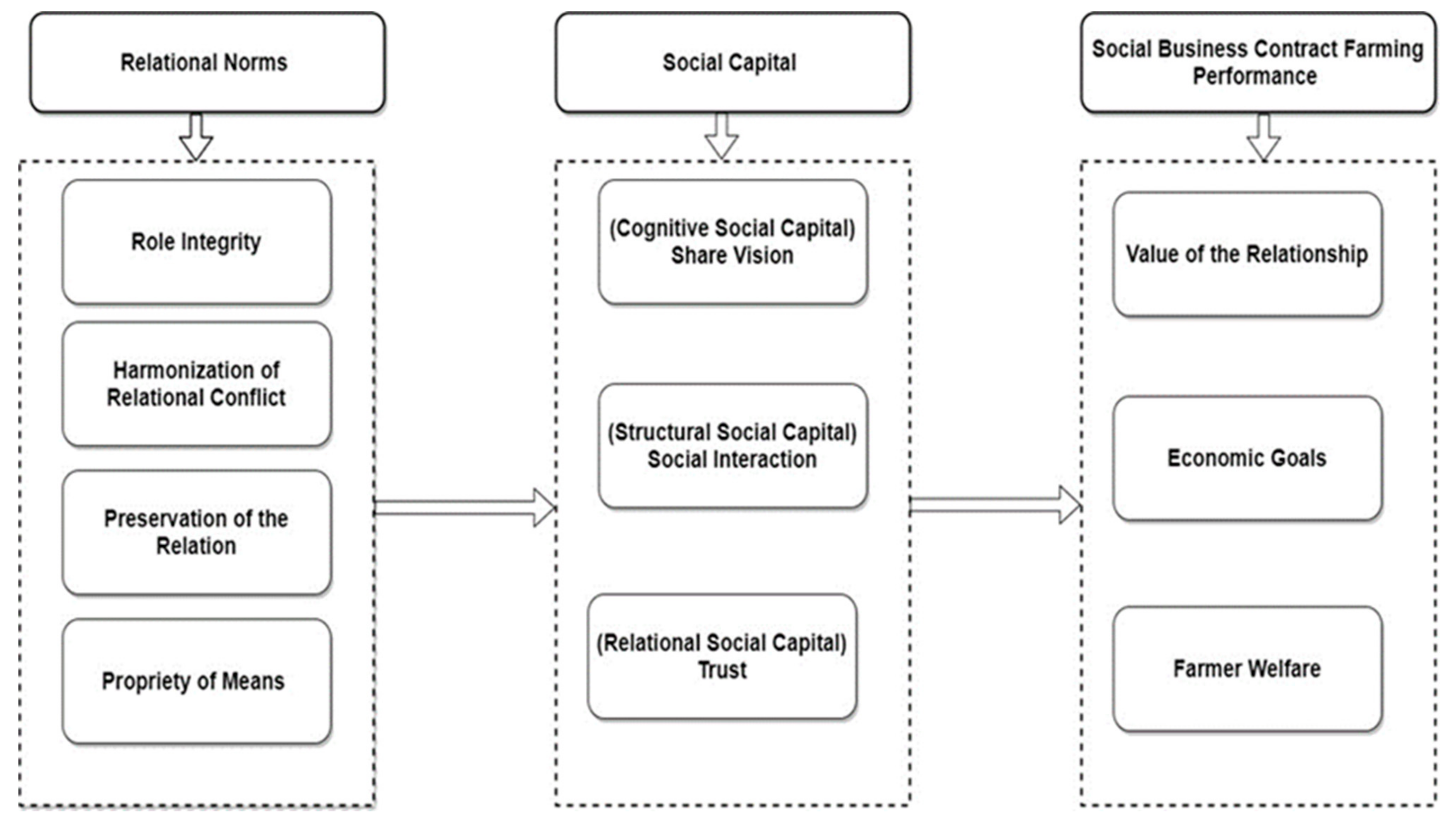

A conceptual framework is a well-organised, analytical tool that logically integrates multiple disparities and contexts of a concept to reach a process that can provide the best possible explanation of the problem under discussion [81]. The growing literature on contract farming and relational contracts shows that contracts, as a sustainable and innovative tool that works towards social business, is and under-investigated area, despite its high importance. Thus, this study makes an important contribution to the development of a conceptual framework that can help to transform contract farming towards social business contract farming and Performance by ensuring small scale farmers’ welfare, along with achieving economic goals. Given the growing attention towards sustainable agriculture contract farming, sustainability-related issues in agriculture, types of contracts and sustainability issues in contract farming performance, and, summarizing the entire discussion on the relationship of social business objective or performance, social capital, and relational norms, this study proposes a conceptual framework in Figure 2 by integrating social capital, along with relational norms in formal contracts to address issues in conventional contract farming. The proposed research framework has been formulated by integrating relational contract norms, along with conventional formal contracts and social capital to link the triple bottom line performance in social business contract farming. The framework consists of three groups of variables, including independent variables, mediating variables, and dependent variables. Independent variables include relational norms (i.e., role integrity, harmonisation of relational conflict, preservation of the relation and the propriety of the means). Dependent variables includes social business contract farming performance (i.e., value of the relationship, farmers’ welfare and economic goals), and mediating variables include social capital dimensions (i.e., cognitive, relational and structural dimensions). For relational norms to have an effective impact on social business performance, these norms should be mediated by social capital variables. This is because the relational norms among producers and agricultural firms will lead to better contract performance only if there is interaction, trust, and a common vision (social capital dimensions) among the two parties. The famers’ welfare and economic goals of farmers and agricultural firms’ achievement may improve contract farming performance that ultimately enhances triple bottom line performance. The improvement in triple bottom line parameters, i.e., social and economic leads towards sustainability in contract farming.

Figure 2.

Social Business Contract Farming Model.

5. Future Direction

The current conceptual study can be tested empirically using a quantitative approach. The current study can be tested in developing countries, including Malaysia. The data can be collected from agricultural sectors and sub-sectors using the survey method via structured questionnaire. The data collected using a survey questionnaire could be analysed using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) due to the strong data, predictive ability and capability of contending with small sample sizes and non-normal data sets [82,83].

6. Discussion on the Proposed Social Business Contract Farming Model

The conventional contract farming model has created monopsony and power imbalance, as small-scale farmers face exploitation by large agricultural firms. Nevertheless, with an increase in asset portfolio, small-scale farmers have shown reluctance towards participating in contract farming. The small-scale farmers participating in the contract farming model are vulnerable to falling into poverty. Researchers have questioned the type of contracts between small scale farmers and agricultural firms. Both formal and relational contracts in agriculture do not guarantee small scale farmers’ welfare.

The challenges in the conventional contract farming model have called for a paradigm shift in contract farming to transform contract farming towards a sustainable innovative solution to help small-scale farmers. Many researchers have stated that conventional business practices are the main cause of environmental and social problems; thus, concern towards sustainability is of critical importance. Sustainable innovation is a broader concept and is not just limited to technology adoption for sustainable production [30]. Sustainable innovation can be viewed as the adoption or introduction of some new processes or business models or business systems to improve performance on the three parameters of the triple bottom line, including environmental, social and economic parameters.

Therefore, this paper proposes a social business contract farming model with the motive to not only achieve the economic goal but also provide a solution to social issues, such as poverty. The proposed model is aligned with the triple bottom line approach, which aims to solve poverty (one of the social issues) and the economic goals of both the farmers and the agricultural firm. Moreover, this paper proposes the applications of relational norms in a formal contract, along with social capital, to enhance the social business contract farming performance by strengthening the value of the relationship, economic goal achievement, and farmers’ welfare. Social capital strengthening schemes, such as cooperatives, are formal structures that may lead to social business. The economic goal achievement and value of the relationship may help in countering social issues, such as poverty. The social business contract farming model as a sustainable innovation tool may enhance the performance of the contract, as sustainable innovation improves the performance of the business. The social business contract farming model can lead to sustainable development by improving the income and welfare of small-scale farmers. Therefore, future studies should empirically test and validate the proposed conceptual framework. The authors expect future studies to test the conceptual framework in different countries with large sample sizes. This will facilitate generalising the framework and will shed light on the impact of relational norms and social capital in formal contracts to create competitive advantage and to achieve sustainable development. The relationships formed between the dependent variables and independent variables in the proposed model are backed by many studies, but the integration of relational norms and social capital as a mediator has not been investigated to date. Future studies should also test other relational norms, social capital and social business contract farming variables to obtain productive theoretical and empirical direction and significance in this particular area of research.

Additionally, the current study encourages contract farming by involving small scale farmers as one of the key stakeholders. There are two main approaches to promote contract farming: the cooperative model and the collaborative model. The cooperative model, or coops, is an improved version of contract farming where farmers come together to form cooperatives. Cooperatives improve the efficiency, transparency, and fairness of the system. A cooperative model may range across various activities of the supply chain, including procurement, storage, processing, distribution and marketing. Similarly, collaborative farming is the type of farming where more than two farmers work together in a formal arrangement for the mutual benefit of all those involved in the arrangement. These farmers act as a third party to buy agricultural products from the farmers, and consolidate and perform cross-docking for the retailers. Collaborative arrangements can offer many benefits to the farmers, including economic, knowledge sharing and social benefits. Collaborative arrangements can help farmers economically by increasing returns through the ability to achieve scale at a lower capital cost, the reduction of costs that are duplicated between farmers, and risk sharing. Finally, the role of the government to promote more sustainable contract farming is imperative. Through various policies and assistance, the social business contract farming model could be realised.

7. Conclusions

By proposing a social business contract farming model, this study helps agriculture firms to improve the conventional contract farming and achieve a balanced performance. The outcomes of this study provide policy insight to the practitioners and policymakers of the agricultural sector and contract farming to achieve higher sustainability in contract farming by reducing the chances of contract violations. This will eventually help social business contract farming to expand internationally, which will holistically contribute towards stability in the contract farming and agricultural sector. Therefore, the completion of this study has some serious implications on the domestic as well as an international agriculture sector. Evidence has shown that the agricultural sector holds a central position in the economic system of developing countries. For the smooth continuation of contract farming, contribution to the economic system and proper working of the agriculture sector, the new contract farming model is strongly required. In the agriculture sector, the evidence shows that the social aspect of the contract farming business is over-sighted. The absence of social business leads to a crisis in agriculture and contract farming. Hence, an efficient social business contract farming model helps to reduce this risk.

7.1. Significance of the Study

The significance of the study in terms of theoretical, methodological and practical is provided below.

7.1.1. Theoretical Contribution

This research privileges novelty by conceptualising the relationship of relational norms, social capital and contract farming for triple bottom line performance. Such implications have not been addressed by past literature. Through conducting this research, this study will enrich the current body of the literature in contract farming, and social business. This study will also add to the body of knowledge using relational norms, relational theory and social capital theory for establishing the link of relational norms as a tool with social business contract farming performance.

7.1.2. Methodological Contribution

By developing a social business contract farming framework, this research will function as a methodological base for measuring the triple bottom line performance in agriculture and other sectors where contracts are in practice. Future research can introduce additional social business governance mechanisms into the measurement framework by implementing the suggested framework which will enhance the accuracy level of measurement frameworks.

7.1.3. Practical Contribution

This study provides a significant practical contribution to improving conventional contract farming. The conceptual framework help governments in developing countries to implement policies and implementation of a more sustainable contract farming.

Conventional agricultural firms can transform their business models to become aligned with triple bottom line parameters. Social business contract farming will ensure small scale farmers wellbeing without sacrificing the economic goals of the agricultural firms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.A. and H.A.; methodology, I.A.A. and H.A.; review and editing, A.J.; supervision, H.A. and A.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We would like to express our gratitude to the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (MOHE) to support this study under the Fundamental Research Grant (FRGS) grant [grant number: FRGS/1/2019/SS01/UTP/02/2] and Yayasan Universiti Teknologi Petronas grant [grant number: 015LC0-203].

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- PedroAzevedo, A.C. A New Profile of the Global Poor. World Dev. 2018, 101, 250–267. [Google Scholar]

- Ncube, D. The Importance of Contract Farming to Small-scale Farmers in Africa and the Implications for Policy: A Review Scenario. Open Agric. J. 2020, 14, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.F.; Eibel-Spanyi, K.; Caddotte, E.R.; Mosca, J.B. Trust as a precursor or outcome of relational norm development: A cross-cultural comparison of US and Hungarian managers. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kozhaya, R. A Systematic Review of Contract Farming, and its Impact on Broiler Producers in Lebanon. Open Sci. J. 2020, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwambi, M.M.; Oduol, J.; Mshenga, P.; Saidi, M. Does contract farming improve smallholder income? The case of avocado farmers in Kenya. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2014, 6, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Role of the State in Contract Farming in Thailand: Experiences and Lessons. ASEAN Econ. Bull. 2002, 22, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.; Phillips-Howard, K. Comparing Contracts: An Evaluation of Contract Farming Schemes in Africa. World Dev. 1997, 25, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M.F.; Bloem, J.R. Does contract farming improve welfare? A review. World Dev. 2018, 112, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armah, J.; Schneider, K.; Plotnick, R.; Gugerty, M. Smallholder Contract Farming in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia; Evans School of Public Affairs: Seattle, WA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- TIsager, L.; Fold, N.; Nsindagi, T. The post-privatization role of out-growers’ associations in rural capital accumulation: Contract farming of sugar cane in Kilombero, Tanzania. J. Agrar. Chang. 2018, 18, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragasa, C.; Lambrecht, I.; Kufoalor, D.S. Limitations of contract farming as a pro-poor strategy: The case of maize outgrower schemes in Upper West Ghana. World Dev. 2018, 102, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J. Contract farming in developing countries: An overview. Wageninge 2008, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng, J.; Owuor, G.; Bebe, B.O. Pattern of Management Interventions’ Adoption and Their Effect on Productivity of Indigenous Chicken in Kenya. AfJARE. 2012, 7, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cahyadi, E.R.; Waibel, H. Contract farming and vulnerability to poverty among oil palm smallholders in Indonesia. J. Dev. Stud. 2016, 52, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenger, C.; Torero, M.; Qaim, M. Impact of third-party contract enforcement in agricultural markets—A field experiment in Vietnam. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1220–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.; Wollni, M. The role of farmers’ trust, risk and time preferences for contract choices: Experimental evidence from the Ghanaian pineapple sector. Food Policy 2018, 81, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruml, A.; Qaim, M. Smallholder Farmers’ Dissatisfaction with Contract Schemes in Spite of Economic Benefits: Issues of Mistrust and Lack of Transparency. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 1106–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, J.D.; Wu, S.Y. Relational contracts in agriculture: Theory and evidence. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneipp, J.M.; Gomes, C.M.; Bichueti, R.S.; Frizzo, K.; Perlin, A.P. Sustainable innovation practices and their relationship with the performance of industrial companies. Rev. Gest. 2019, 26, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michler, J.D.; Wu, S.Y. They note a significant amount of contract noncompliance as well as considerable churn in the market as farmers and firms enter and exit frequently. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drescher, K. Assessing aspects of agricultural contracts: An application to German agriculture. Agribusiness 2000, 16, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, R.; Suri, T. Endogenous emergence of credit markets: Contracting in response to a new technology in Ghana. J. Dev. Econ. 2013, 101, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Investigating Social Entrepreneurship: A Multidimensional Model. J. World Bus. 2006, 4, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.; Carroll, G.R.; Hannan, M.T. The Liability of Newness: Age Dependence in Organizational Death Rates. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M.T.; Dacin, P.A.; Tracey, P. Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, G.; Monticelli, J.M.; Vargas Bortolaso, I. Social Capital as a Driver of Social Entrepreneurship. J. Soc. Entrep. 2021, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, F.; Strebel, H. Incremental, radical and game changing: Strategic innovation for sustainability. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehber, E. Contract Farming: Theory and Practice CFA; ICFAI University Press: Hyderabad, India, 2007; pp. 1–167. [Google Scholar]

- Michelini, L.; Fiorentino, D. New business models for creating shared value. Soc. Responsib. J. 2012, 8, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. Building Social Business—The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pamuk, H.; Bulte, E.; Adekunle, A.; Diagne, A. Decentralised innovation systems and poverty reduction: Experimental evidence from Central Africa. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2015, 42, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigenberg, B.; Field, E.; Pande, R. The Economic Returns to Social Interaction: Experimental Evidence from Microfinance. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2013, 80, 1459–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiso, L.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes? J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macneil, I.R. The New Social Contract: An Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay, S. Non-contractual relations in business: A preliminary study. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1963, 28, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olounlade, O.A.; Gu-Cheng, L.; Traoré, L.; Dossouhoui, F.V.E.; Biaou, G. Reputation effect of the moral hazard on contract farming market development: Game theory application on rice farmers in Benin. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 14, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pultrone, C.; da Silva, C.A.; Caro, C.B. Legal fundamentals for the design of contract farming agreements. Sustain. Mark. Agribus. Rural. Transform. 2017, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, J.; McLaughlin, J.; Elaydi, R. Ian Macneil and relational contract theory: Evidence of impact. J. Manag. Hist. 2014, 20, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdoci, B.; Skreli, E.; Imami, D. Relational governance—An examination of the apple sector in Albania. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2015, 16, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NigelKey, M. The Social Performance and Distributional Consequences of Contract Farming: An Equilibrium Analysis of the Arachide de Bouche Program in Senegal. World Dev. 2002, 30, 255–263. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, W.; Ratanawaraha, A.; Diskul, D.; Chandrachai, A. Social Entrepreneurship as a Mechanism for Agro-Innovation: Evidence from Doi Tung Development Project, Thailand. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Heide, J.B.; John, G. Do norms matter in marketing relationships? J. Mark. 2016, 56, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, B.; Fu, D.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, J. Curbing opportunism in logistics outsourcing relationships: The role of relational norms and contract. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 182, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, B.; Yilmaz, C. Relative effects of dependence and trust on flexibility, information exchange, and solidarity in marketing channels. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2007, 22, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, K. Business to business exchanges: A rich descriptive apparatus derived from Macneil’s and Menger’s analyses. J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 523–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivens, B.S.; Blois, K.J. Relational exchange norms in marketing: A critical review of Macneil’s contribution. Mark. Theory 2004, 4, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlina, N.; Rusli, B. An Analysis of Social Capital in Empowerment Community at Uninhabitable House’s Renovation Fund Onwest Bandung Regency. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprapto, M.; Bakker, H.L.; Mooi, H.G.; Moree, W. Sorting out the essence of owner–contractor collaboration in capital project delivery. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungu, L.J. Factors Influencing Establishment of Indigenous Chicken Value Chain in Hamisi Constituency; University of Nairobi: Vihiga County, Kenya, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, S.; Tian, C.; Guo, H. How Do Relational Contracting Norms Affect IPD Teamwork Effectiveness? A Social Capital Perspective. Proj. Manag. J. 2020, 51, 538–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V.M.; Sorenson, D.; Henchion, M.; Gellynck, X. Social capital and knowledge sharing performance of learning networks. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T. Study of Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation Ecosystems in South East and East Asian Countries; The Japan Research Institute: Tokio, Japan, 2016; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Sønderskov, K.M. Is Social Capital a Good Concept? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1225–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J. Sosial Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Am. J. Sociol. 2010, 94, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, F. Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R. Notes on Social Capital and Economic Perfomance. In Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective; Dasgupta, P., Serageldin, I., Eds.; A Multifaceted Prespective; World Bank: Trento, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Bowling Alone—The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, L. Beyond Relational Contracts: Social Capital and Network Governance in Procurement Contracts. J. Leg. Anal. 2016, 7, 561–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.V.P.I.; Priyanath, H.M.S. Relational Norms, Opportunism and Business Performance: An Empirical Evidence of Gem Dealers in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J. Econ. Res. 2017, 6, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education; Richardson, J.G., Ed.; Greenwood Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Luño, A.; Medina, C.C.; Lavado, A.C.; Rodríguez, G.C. How social capital and knowledge affect innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Nohria, N.; Zaheer, A. Strategic networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 21, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.H.; Revilla, E.; Choi, T.Y. The dark side of buyer-supplier relationships: A social capital perspective. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Abdul Aziz, A.; Williams, A. Assessing yield and yield stability of hevea clones in the southern and central regions of Malaysia. Agronomy 2020, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, J.W. Information sources for modeling the national economy. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1980, 75, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saryazdi, A.H.G.; Ghatari, A.R.; Mashayekhi, A.; Hassanzadeh, A. Designing a qualitative system dynamics model of crowdfunding by document model building. Qual. Res. Financ. Mark. 2020, 12, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, S.A.; Weatherston, J. The benefits of online crowdfunding for fund-seeking business ventures. Strateg. Chang. 2014, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, M.; Hirsch, D.; Pahl-Wostl, C. Coping with change: Responses of the Uzbek water management regime to socio-economic transition and global change. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G. Guidance Notes on Planning A Systematic Review, James Hardiman Library. 2010. Available online: http://www.library.nuigalway.ie/media/jameshardimanlibrary/- (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Zurynski, Y. Writing a Systematic Literature Review, Resources for Students and Trainees, Australian Pediatric Survellance Unit APSU; 2014. Available online: http://www.apsu.org.au/assets/Resources/Writing-a-Systematic-Literature-Review.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Syarifudin, D.F.I. European Association of Agricultural Economists. J. Wil. Lingkung. 2020, 8, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Han, J. The effects of social capital on farmers’ wellbeing in China’s undeveloped poverty-stricken areas. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahy, J. The Resource-based View of the Firm: Some Stumbling-blocks on the Road to Understanding Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2000, 24, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M. Vertical Integration: Determinants and Effects. In Handbook of Industrial Organization; Schmalensee, R., Willing, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 183–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Na, Y.K. The Effect of the Relationship Characteristics and Social Capital of the Sharing Economy Business on the Social Network, Relationship Competitive Advantage, and Continuance Commitment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A. High- and Low-Performance Firms: Do They Have Different Profiles of Perceived Core Intangible Resources and Business Environment. Technovation 2001, 21, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.; Messenger Davies, M.; Allan, S.; Mendes, K.; Milani, R.; Wass, L. What Do Children Want from the BBC? Children’s Content and Participatory Environments in the Age of Citizen Media. AHRC/BBC; Cardiff University: Cardiff, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Rao, P. A conceptual framework for identifying financing preferences of SMEs. Small Enterpr. 2015, 22, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).