How Does the Social Support Affect Refugees’ Life Satisfaction in Turkey? Stress as a Mediator, Social Aids and Coronavirus Anxiety as Moderators

Abstract

:1. Introduction

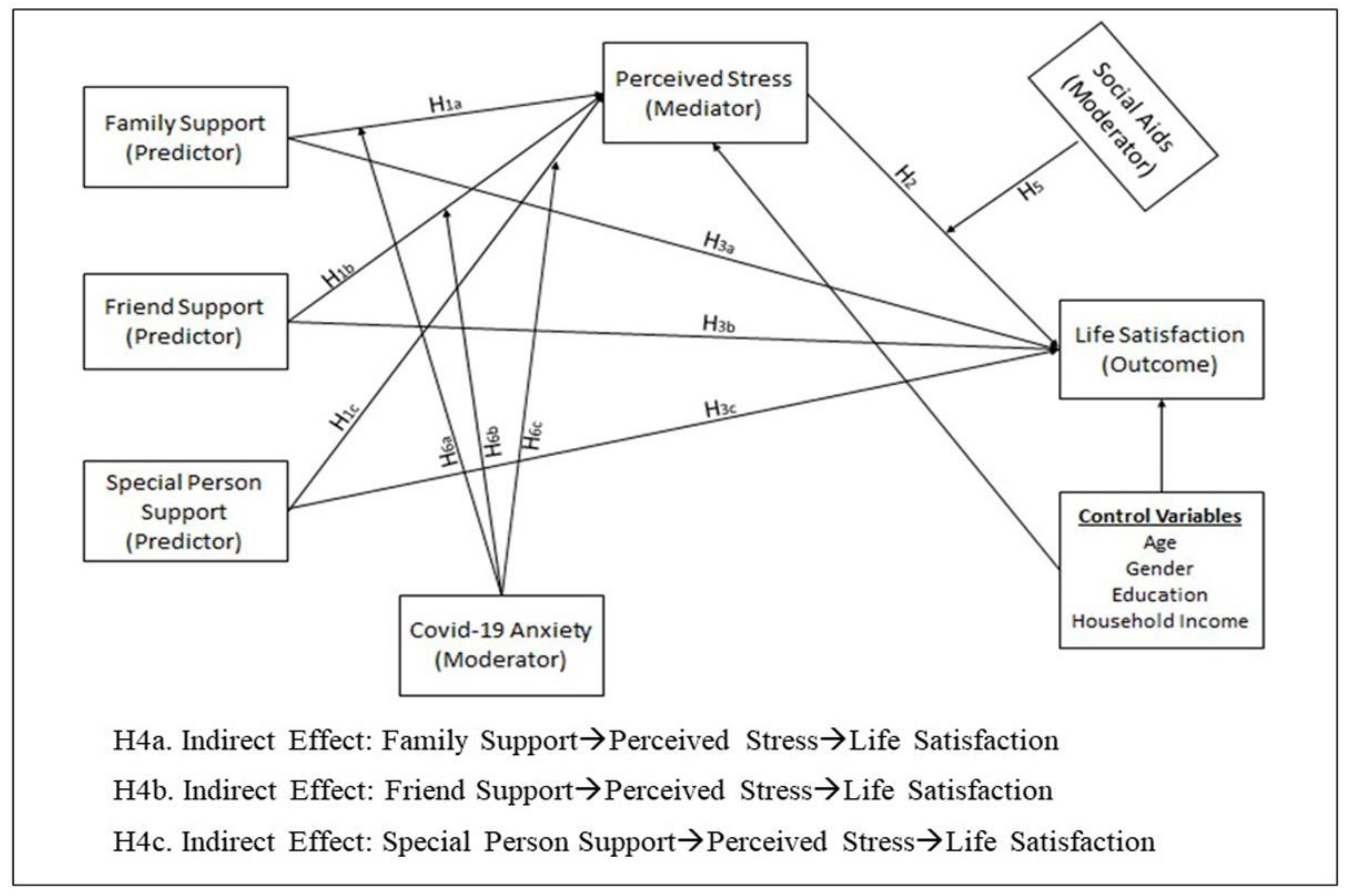

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Frequencies of Demographic Variables

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results

4.3. Correlation Analysis Results

4.4. Multiple Regression Analysis Results

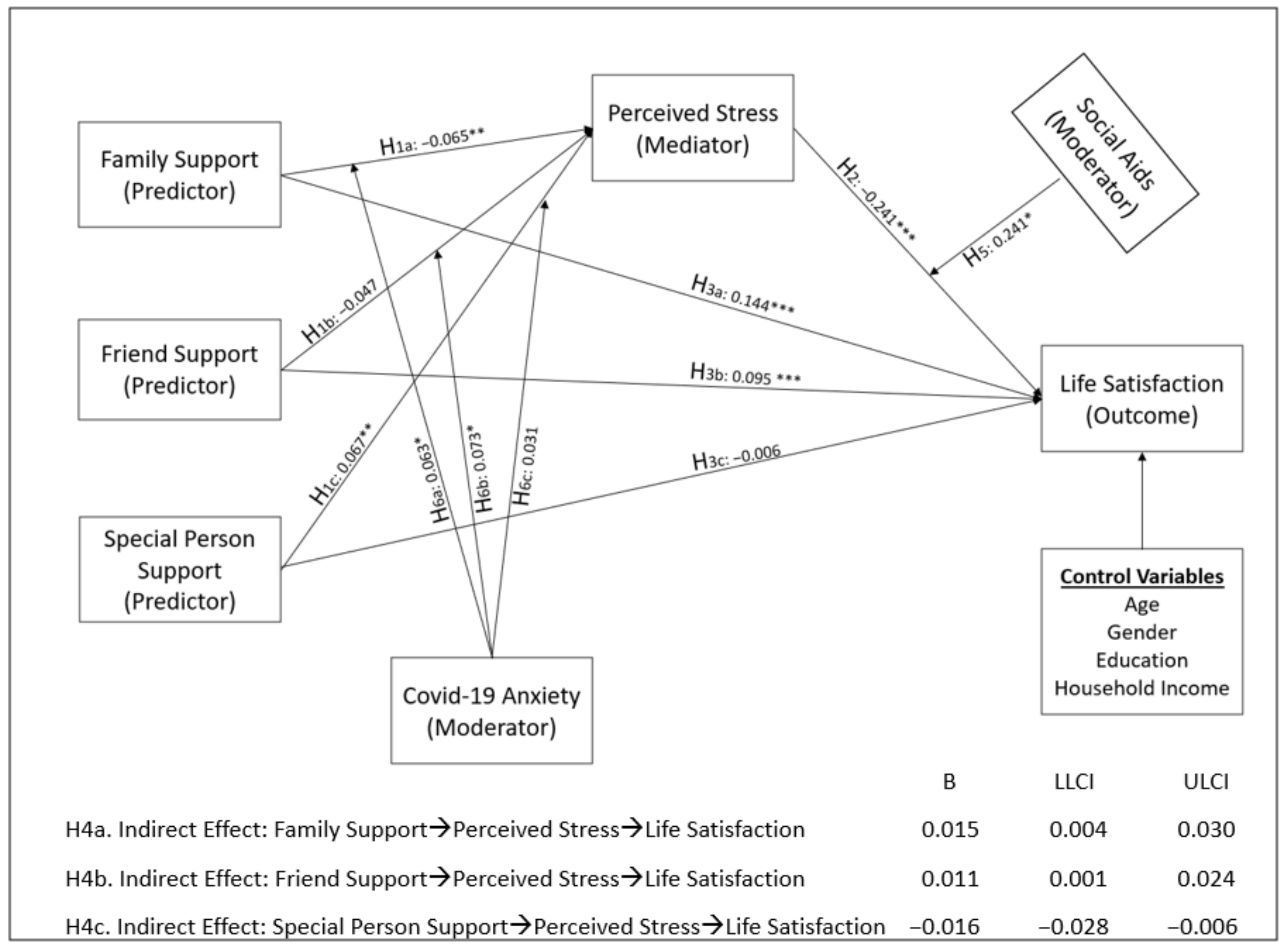

4.5. Mediation Analysis Results

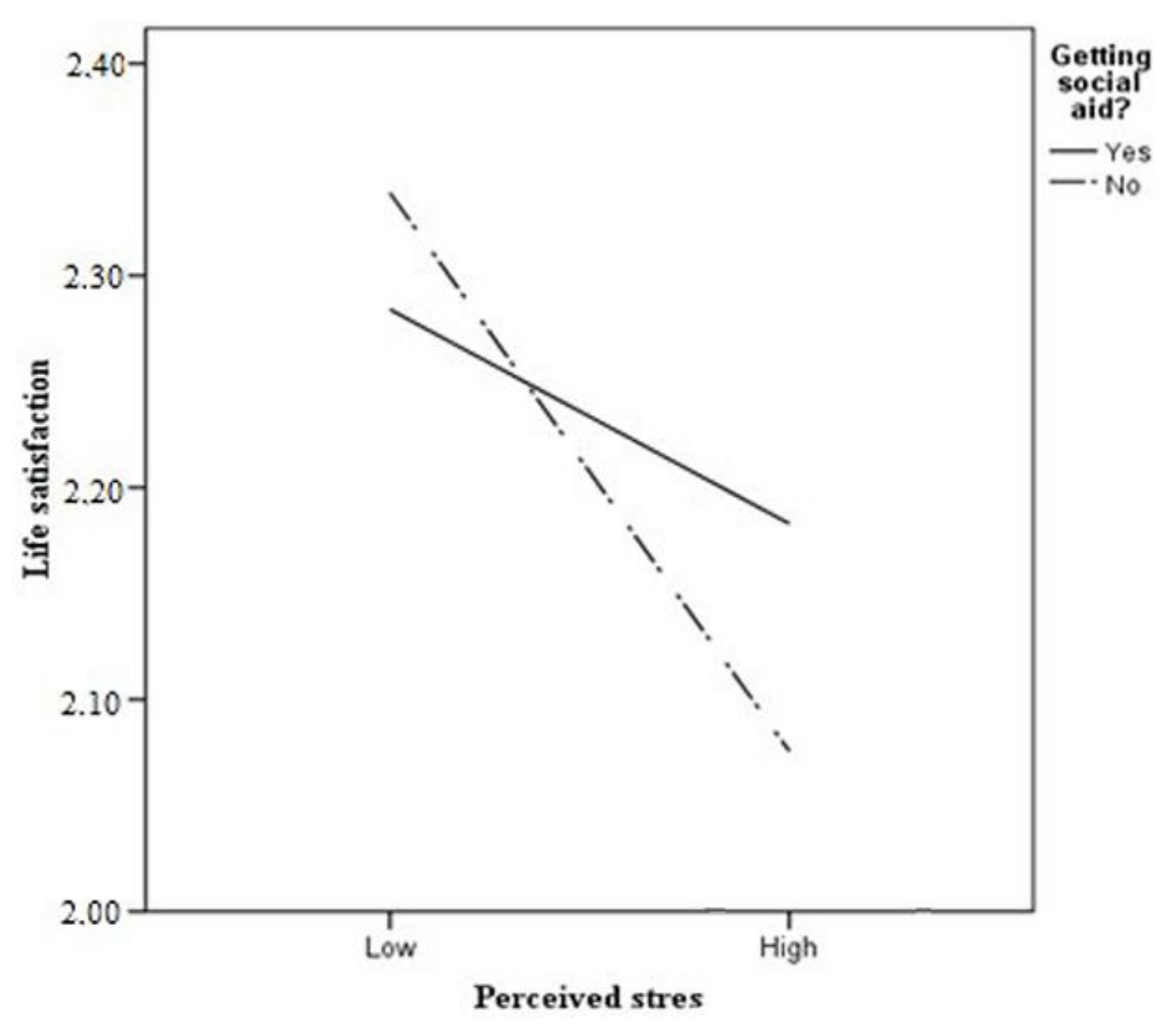

4.6. Moderation Analysis Results

4.7. Results of the Research Model

5. Discussion

6. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dingle, H.; Drake, V.A. What is Migration? Bioscience 2007, 57, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: http://www.unhcr.org/56cad5a99.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Available online: http://www.bbc.com/turkce/multimedya/2012/06/120627_dg_syria (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Directorate General of Migration Management. Available online: https://en.goc.gov.tr/temporary-protection27 (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Karadağ, O.; Altıntaş, K.H. Mülteciler ve Sağlık. TAF Prev. Med. Bull. 2010, 9, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Priebe, S.; Giacco, D.; El-Nagib, R. Public Health Aspects of Mental Health among Migrants and Refugees: A Review of the Evidence on Mental Health Care for Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Irregular Migrants in the WHO European Region; Health Evidence Network (HEN) Synthesis Report 47; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, L.H.; Cerqueira, R.O.; Leclerc, E.; Brietzke, E. Stress, Trauma, And Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Migrants: A Comprehensive Review. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2018, 40, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being. Indian J. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 24, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Simich, L.; Beiser, M.; Stewart, M.; Mwakarimba, E. Providing Social Support for Immigrants and Refugees in Canada: Challenges and Directions. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2005, 7, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, I.P.; Cox, B.J.; Enns, M.W.; Murray, L.T.; Torqrudc, L.J. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Clinically Distressed and Student Samples. J. Personal. Assess. 2003, 81, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, A.; Espinoza, M.D.C.; Boudesseul, J.; Heimark, K. Venezuelan Forced Migration to Peru During Sociopolitical Crisis: An Analysis of Perceived Social Support and Emotion Regulation Strategies. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2021, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVoretz, D.J.; Pivnenko, S.; Beiser, M. The Economic Experiences of Refugees in Canada (March 2004). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=526022 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Bostan, S.; Erdem, R.; Öztürk, Y.E.; Kılıç, T.; Yılmaz, A. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Turkish Society. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekmen, E.; Koçak, O. Göçün Suriyeli ve Yemenli Göçmenlerin Aile Yapıları Üzerine Etkileri. J. Soc. Policy Conf. 2020, 79, 167–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, A.U.; Budak, S.N.; Budak, B.; Özkan, S.; İlhan, M.N. COVID-19 Salgınında Savunmasız Gruplardan Biri: Göçmenler. Gazi. Med. J. 2020, 31, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macapagal, P.M. COVID-19: Psychological Impact. Afr. J. Biol. Med. Res. 2020, 3, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, I. Algılanan Sosyal Destek Ölçeğinin Geliştirilmesi Güvenirliği ve Geçerliliği. Hacet. Univ. J. Educ. 1997, 13, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, J.A.; Paisley, C.A.; Mulla, M.M.; Tomeny, T.S. Unmet Social Support Needs among College Students: Relations between Social Support Discrepancy and Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social Support as a Moderator of Life Stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baltaş, Z. Sağlık Psikolojisi; Remzi Press: Istanbul, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Daalen, V.G.; Sanders, K.; Willemsen, T.M. Sources of Social Support as Predictors of Health, Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction among Dutch Male and Female Dual-Earners. Women Health 2005, 41, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheny, K.B.; Curlette, W.L.; Aysan, F.; Herrington, A.; Gfroerer, C.A.; Thompson, D.; Hamarat, E. Coping Resources, Perceived Stress, and Life Satisfaction among Turkish and American University Students. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2002, 9, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çivitci, A. Perceived Stress and Life Satisfaction in College Students: Belonging and Extracurricular Participation as Moderators. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2005, 205, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Temiz, Z.T.; Gökçek, V.U. Yurtta Kalan Üniversite Öğrencilerinin Anksiyete, Sosyal Destek Ve Yaşam Doyum Düzeyleri ile Baş Etme Stillerinin İncelenmesi. FSM Sch. Stud. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2020, 15, 431–458. [Google Scholar]

- Frijters, P.; Haisken-Denew, J.P.; Shields, M.A. Money Does Matter! Evidence from Increasing Real Income and Life Satisfaction in East Germany Following Reunification. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Schönfeld, P.; Kochetkov, Y.; Margraf, J. What Does Migration Mean to Us? USA and Russia: Relationship between Migration, Resilience, Social Support, Happiness, Life Satisfaction, Depression, Anxiety and Stress. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, F.F.; Korkmaz, F. Algılanan Sosyal Destek İle Stres Düzeyleri Arasındaki İlişkinin İncelenmesi: Üniversite Öğrencileri Üzerine Bir Araştırma. Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi İktisadi Ve İdari Bilimler Dergisi 2019, 20, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzi, C.; Tucci, M.; Ciprandi, R.; Brambilla, I.; Caimmi, S.; Ciprandi, G.; Marseglia, G.L. The Psycho-Social Effects of COVID-19 on Italian Adolescents’ Attitudes and Behaviors. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, D.; Arkar, H.; Yaldiz, H. Çok Boyutlu Algılanan Sosyal Destek Ölçeği’nin Gözden Geçirilmiş Formunun Faktör Yapısı, Geçerlik ve Güvenirliği. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2001, 12, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.A. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A Brief Mental Health Screener for COVID-19 Related Anxiety. Death Stud. 2020, 44, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biçer, I.; Çakmak, C.; Demir, H.; Kurt, M.E. Koronavirüs Anksiyete Ölçeği Kısa Formu: Türkçe Geçerlik ve Güvenirlik Çalışması. Anatol. Clin. J. Med. Sci. (Spec. Issue COVID 19) 2020, 25, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gürbüz, S.; Şahin, F. Sosyal Bilimlerde Araştırma Yöntemleri; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, B.; Kim, J.Y.; DeVylder, J.E.; Song, A. Family Functioning, Resilience, and Depression among North Korean Refugees. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 245, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, L.; Liamputtong, P. Acculturation Stress and Social Support for Young Refugees in Regional Areas. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 77, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottvall, M.; Vaez, M.; Saboonchi, F. Social Support Attenuates the Link between Torture Exposure and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder among Male and Female Syrian Refugees in Sweden. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, R.A.; Galvan, H.F.; Myers, F.H.; Garland, W.; George, S.; Witt, M.; Cadden, J.; Operskalski, E.; Jordan, W.; Carpio, F. Social Support, Stress and Social Network Characteristics among HIV-Positive Latino and African American Women and Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2010, 14, 1149–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.M.; Park, J.W.; Kang, H.S. Relationships of Acculturative Stress, Depression, and Social Support to Health-Related Quality of Life in Vietnamese Immigrant Women in South Korea. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2014, 25, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, İ.F. Algılanan Sosyal Destek ile Yaşam Tatmini ve Özgüven İlişkisi: Göçmenler Üzerinde bir Araştırma. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Derg. 2019, 12, 586–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.S. Impacts of Social Support and Life Satisfaction on Depression among International Marriage Migrant Women in Daegu and Kyungpook Area. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 20, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamarat, E.; Thompson, D.; Steele, D.; Matheny, K.; Simons, C. Age Differecens in Coping Resources and Saticfaction with Life among Middle-Aged, Young-Old, and Oldest Old Adults. J. Genet. Psychol. 2002, 163, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.W.; Park, H.; Kim, M.; Kwon, Y.D.; Kim, J.S.; Yu, S. The Effects of Discrimination Experience on Life Satisfaction of North Korean Refugees: Mediating Effect of Stress. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bilen, D. Suriyeli Mültecilerde Travma Sonrası Stres Bozukluğu ve Yaşam Doyumu Düzeyinin Çeşitli Değişkenlere Göre İncelenmesi. Master’s Thesis, Çağ University, Mersin, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asmar, I.T.; Al-Shami, N.; Karsh, A.A.; AlFayyah, F.A.; Ro’a, M.D.; Jaghama, M.K.; Naseef, H. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Psychological Status of Palestinian Adults in the West Bank, Palestine; A Cross Sectional Study. Open Psychol. J. 2020, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.X.; Ng, J.C.K.; Hui, B.P.H.; Au, A.K.Y.; Wu, W.C.H.; Lam, B.C.P.; Mak, W.W.S.; Liu, J.H. Dual Impacts of Coronavirus Anxiety on Mental Health in 35 Societies. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieffien, W.; Law, S.; Andermann, L. Immigrant and Refugee Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Additional Key Considerations. Can. Fam. Physician 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, B.; Schetter, D.C.; Abdou, M.C.; Hobel, J.C.; Glynn, M.L.; Sandman, A. Familialism, Social Support, and Stress: Positive Implications for Pregnant Latinas. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minority Psychol. 2008, 14, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rabbani, M.; Mansor, B.M.; Yaacob, N.S.; Talib, A.M. The Relationship between Social Support, Coping Strategies, and Stress among Iranian Adolescents Living in Malaysia. Online J. Couns. Educ. 2014, 3, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, J. We were Already Strong: Young Refugees, Challenges, and Participation during COVID-19. J. Soc. Incl. 2021, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Multicultural Youth Advocacy Network. COVID-19 and Young People from Refugee and Migrant Backgrounds; Multicultural Youth Advocacy Network: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 280 | 44.6 |

| Female | 348 | 55.4 |

| Total | 628 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| 18–25 | 229 | 36.5 |

| 26–35 | 245 | 39.0 |

| 36–45 | 105 | 16.7 |

| 46–65 | 49 | 7.8 |

| Total | 628 | 100 |

| Education status | ||

| Primary School Graduate | 66 | 10.5 |

| Secondary School Graduate | 101 | 16.1 |

| High School Graduate | 151 | 24.0 |

| University and Post Graduate | 310 | 49.4 |

| Total | 628 | 100 |

| Household income | ||

| 2000 TL1 ($229) and less | 268 | 42.7 |

| 2001–4000 TL ($230–$460) | 218 | 34.7 |

| 4001–6000 TL ($461–$692) | 86 | 13.7 |

| 6001–9000 TL ($693–$1038) | 34 | 5.4 |

| 9001 TL ($1039) and more | 22 | 3.5 |

| Total | 628 | 100 |

| Do you get social aid? | ||

| Yes | 180 | 28.7 |

| No | 448 | 71.3 |

| Total | 628 | 100 |

| Indexes | Values | Acceptable Values |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | 2.525 | <5 |

| GFI | 0.904 | >0.90 |

| CFI | 0.939 | >0.90 |

| NFI | 0.903 | >0.90 |

| RMSEA | 0.049 | <0.08 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family support | – | |||||

| 2. Friend support | 0.550 ** | – | ||||

| 3. Special person support | 0.385 ** | 0.554 ** | – | |||

| 4. Perceived stress | −0.130 ** | −0.088 * | 0.049 | – | ||

| 5. Life satisfaction | 0.344 ** | 0.299 ** | 0.158 ** | −0.239 ** | – | |

| 6. Coronavirus anxiety | −0.036 | −0.018 | 0.077 | 0.269 ** | −0.014 | – |

| M | 5.13 | 4.40 | 4.05 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 1.41 |

| SD | 1.42 | 1.52 | 1.64 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.66 |

| Variables | Model 1: PS | Model 2: LS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Constant | 2.481 *** | 0.189 | 1.463 *** | 0.249 |

| FAS | −0.065 ** | 0.023 | 0.144 *** | 0.027 |

| FRS | −0.047 | 0.024 | 0.095 *** | 0.028 |

| SPS | 0.067 ** | 0.020 | −0.006 | 0.024 |

| PS | - | - | −0.241 *** | 0.046 |

| Control Variables | ||||

| Age | −0.028 | 0.030 | 0.074 * | 0.035 |

| Gender | −0.004 | 0.056 | 0.034 | 0.066 |

| Education status | 0.006 | 0.027 | −0.013 | 0.032 |

| Household income | 0.002 | 0.027 | −0.030 | 0.031 |

| R2 | 0.035 | 0.181 | ||

| F | 3.255 | 17.07 | ||

| p | <0.01 | <0.001 | ||

| B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect of FAS on LS | 0.160 | 0.028 | 0.105 | 0.214 | ||||

| Direct effect of FAS on LS | 0.144 | 0.027 | 0.090 | 0.198 | ||||

| Total effect of FRS on LS | 0.107 | 0.029 | 0.050 | 0.163 | ||||

| Direct effect of FRS on LS | 0.095 | 0.028 | 0.040 | 0.151 | ||||

| Total effect of SPS on LS | −0.022 | 0.024 | −0.069 | 0.025 | ||||

| Direct effect of SPS on LS | −0.006 | 0.024 | −0.053 | 0.041 | ||||

| Indirect Path | B | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| Independent | Mediator | Dependent | ||||||

| FAS | > | PS | > | LS | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.030 |

| FRS | > | PS | > | LS | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.024 |

| SPS | > | PS | > | LS | −0.016 | 0.006 | −0.028 | −0.006 |

| Variables | Model 1: PS | Model 2: PS | Model 3: PS | Model 4: LS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Constant | −0.021 | 0.179 | 0.099 | 0.201 | 0.470 * | 0.189 | 1.688 *** | 0.21 |

| Age | −0.041 | 0.029 | −0.039 | 0.030 | −0.037 | 0.030 | 0.076* | 0.035 |

| Gender | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.054 | 0.020 | 0.054 | 0.030 | 0.066 |

| ES | 0.004 | 0.026 | 0.006 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.026 | −0.014 | 0.032 |

| HI | 0.014 | 0.026 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.016 | 0.026 | −0.034 | 0.315 |

| FAS | −0.055 * | 0.022 | −0.059 ** | 0.022 | −0.059 ** | 0.022 | 0.143 *** | 0.273 |

| FRS | −0.038 | 0.023 | −0.033 | 0.023 | −0.039 | 0.023 | 0.095 *** | 0.029 |

| SPS | 0.050* | 0.020 | 0.050 * | 0.020 | 0.052 ** | 0.020 | −0.006 | 0.023 |

| CA | 0.286 *** | 0.041 | 0.275 *** | 0.040 | 0.266 *** | 0.041 | - | - |

| PS | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.311 *** | 0.055 |

| SA | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.006 | 0.074 |

| PS X SA | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.241 * | 0.101 |

| FAS X CA | 0.063 * | 0.027 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FRS X CA | - | - | 0.073 * | 0.029 | - | - | - | - |

| SPS X CA | - | - | - | - | 0.031 | 0.025 | - | - |

| R2 | 0.108 | 0.101 | 0.103 | 0.188 | ||||

| F | 8.322 | 8.458 | 7.848 | 14.30 | ||||

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ekmen, E.; Koçak, O.; Solmaz, U.; Kopuz, K.; Younis, M.Z.; Orman, D. How Does the Social Support Affect Refugees’ Life Satisfaction in Turkey? Stress as a Mediator, Social Aids and Coronavirus Anxiety as Moderators. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212727

Ekmen E, Koçak O, Solmaz U, Kopuz K, Younis MZ, Orman D. How Does the Social Support Affect Refugees’ Life Satisfaction in Turkey? Stress as a Mediator, Social Aids and Coronavirus Anxiety as Moderators. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212727

Chicago/Turabian StyleEkmen, Eymen, Orhan Koçak, Umut Solmaz, Koray Kopuz, Mustafa Z. Younis, and Deniz Orman. 2021. "How Does the Social Support Affect Refugees’ Life Satisfaction in Turkey? Stress as a Mediator, Social Aids and Coronavirus Anxiety as Moderators" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212727

APA StyleEkmen, E., Koçak, O., Solmaz, U., Kopuz, K., Younis, M. Z., & Orman, D. (2021). How Does the Social Support Affect Refugees’ Life Satisfaction in Turkey? Stress as a Mediator, Social Aids and Coronavirus Anxiety as Moderators. Sustainability, 13(22), 12727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212727