Examining Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Tourism for International Tourists

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“Never before in history has international travel been restricted in such an extreme manner” [1].

“What are factors that could potentially increase the intention of young tourists to adopt and recommend a vaccine tourism package?”

2. Literature Review

2.1. Medical Tourism

2.2. Vaccine Tourism

2.3. Young Tourists and Medical Tourism

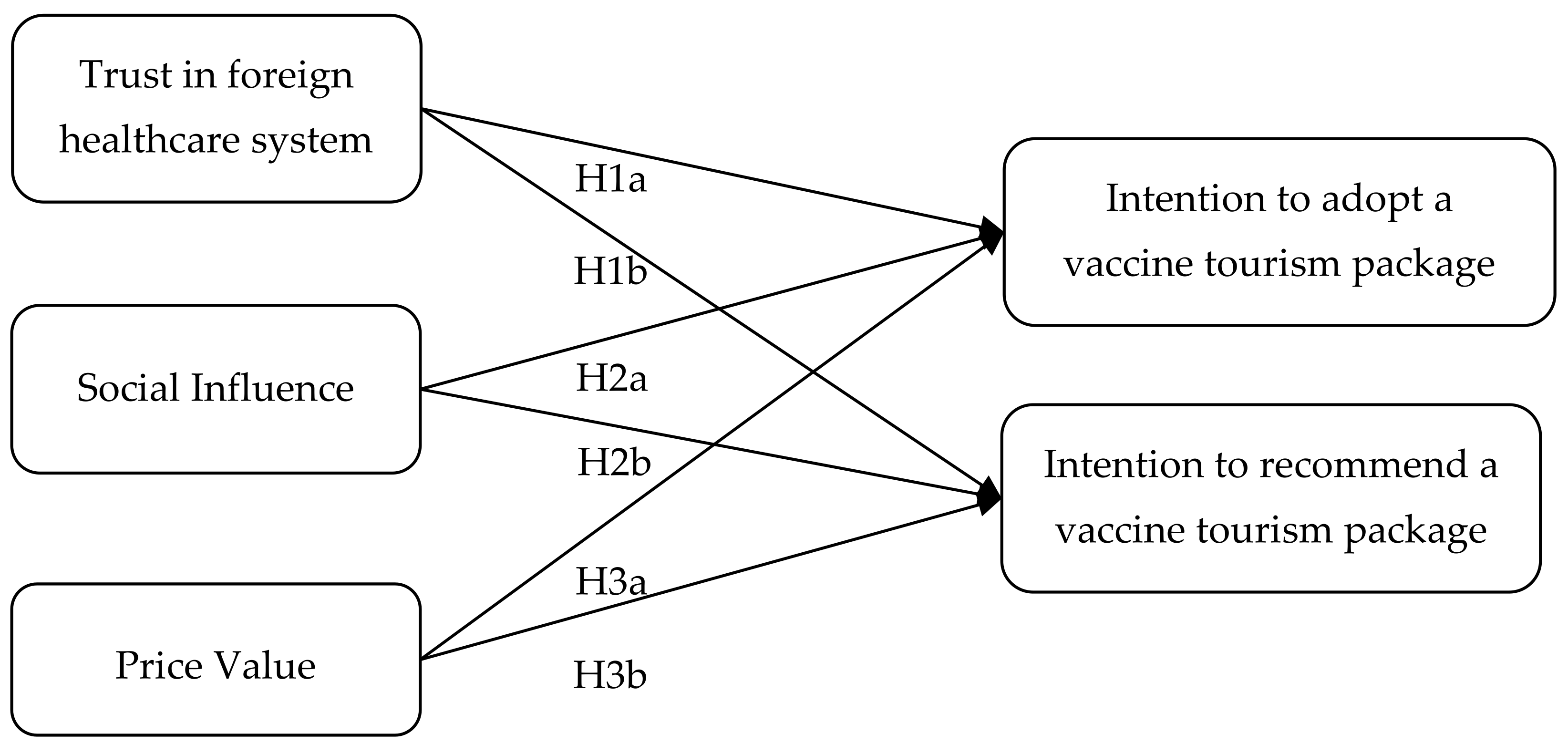

3. The Proposed Research Model

3.1. An Intention to Adopt a Vaccine Tourism Package and an Intention to Recommend a Vaccine Tourism Package

3.2. Trust in the Foreign Healthcare System and Its Impact on Vaccine Tourism Adoption and Recommendation

3.3. Social Influence and Its Impact on Vaccine Tourism Adoption and Recommendation

3.4. Price Value and Its Impact on Vaccine Tourism Adoption and Recommendation

4. Research Method

4.1. Survey Instrument

4.2. Measurement

4.3. Path and Model Estimation

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

5.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Managerial Implications

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/198651593536242978/pdf/COVID-19-and-Tourism-in-South-Asia-Opportunities-for-Sustainable-Regional-Outcomes.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Polyzos, S.; Huan, T.-C.T. The good, the bad and the ugly on COVID-19 tourism recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.-S.; Wu, W.-D. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry: Applying TRIZ and DEMATEL to construct a decision-making model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Q.A.; Haider, S.; Ali, F.; Naz, S.; Ryu, K. Depletion of psychological, financial, and social resources in the hospitality sector during the pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.T.; Park, J.; Li, S.; Song, H. Social costs of tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Travel Largely on Hold Despite Uptick in May. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/taxonomy/term/347 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Fayissa, B.; Nsiah, C.; Tadasse, B. Impact of tourism on economic growth and development in Africa. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brohman, J. New directions in tourism for third world development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, M.; Fiore, Q. War and Peace in the Global Village: An. Inventory of Some of the Current Spastic Situation That Could Be Eliminated by More Feedforward; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. On the mobility of tourism mobilities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Čavlek, N. Economic globalisation and tourism. In Handbook of Globalisation and Tourism; Timothy, D.J., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Surrey, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, A.V.; Alford, P. The effects of globalisation on tourism promotion. In Tourism in the Age of Globalization; Cooper, C., Wahab, S., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2001; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewkhunok, S. The commodification of culture: Bhutan’s tourism in globalisation context. Thammasat Rev. 2018, 21, 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kaewkitipong, L. The Thai medical tourism supply chain: Its stakeholders, their collaboration and information exchange. Thammasat Rev. 2018, 21, 60–90. [Google Scholar]

- Behsudi, A. Wish you were here. Financ. Dev. 2020, 57. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/12/impact-of-the-pandemic-on-tourism-behsudi.htm (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Madeira, A.; Palrão, T.; Mendes, A.S. The impact of pandemic crisis on the restaurant business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, A.; Shikha, F.A.; Hasanat, M.W.; Arif, I.; Hamid, A.B.A. The effect of Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the tourism industry in China. Asian J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2020, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Şengel, Ü.; Çevrimkaya, M.; Genç, G.; Işkın, M.; Zengin, B.; Sarıışık, M. An assessment on the news about the tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Can, A.S.; Williams, N.; Ekinci, Y. Evolving impacts of COVID-19 vaccination intentions on travel intentions. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Requirement for Proof of Negative COVID-19 Test or Recovery from COVID-19 for All Air Passengers Arriving in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/travelers/testing-international-air-travelers.html (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Matsuura, H. World Committee on Tourism Ethics (WCTE) recommendation on COVID-19 certificates for international travel. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Africa Faces 470 Million COVID-19 Vaccine Shortfall in 2021. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/africa-faces-470-million-COVID-19-vaccine-shortfall-2021 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Loss, L. COVID-19: Vaccine Tourism Is Developing around the World. 2021. Available online: https://www.tourism-review.com/vaccine-tourism-setting-off-around-the-world-news11879 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Forman, R.; Shah, S.; Jeurissen, P.; Jit, M.; Mossialos, E. COVID-19 vaccine challenges: What have we learned so far and what remains to be done? Health Policy 2021, 125, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, T.K. Challenges in the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines worldwide. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, e42–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, J.P.; Perrin, P.B.; Laestadius, L.I.; Vraga, E.K.; Miller, C.A.; Fuemmeler, B.F.; Burton, C.W.; Ryan, M.; Carlyle, K.E. US public support for COVID-19 vaccine donation to low-and middle-income countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2452–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S. Decoding the global trend of “vaccine tourism” through public sentiments and emotions: Does it get a nod on Twitter? Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F.; Bigby, B.C.; Doering, A. Socialising tourism after COVID-19: Reclaiming tourism as a social force? J. Tour. Futures 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheţe, A.M. The importance of youth tourism. Ann. Univ. Oradea Econ. Sci. Ser. 2015, 1, 688–694. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, V.A.; Kingsbury, P.; Snyder, J.; Johnston, R. What is known about the patient’s experience of medical tourism? A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chongthanavanit, P.; Cho, S.K.; Mamani, N.C.; Kheokao, J. Comparing country-of-origin image (COI) between trust dimension and purchase intention in dental tourism. Thammasat Rev. 2021, 24, 197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Heung, V.C.; Kucukusta, D.; Song, H. A conceptual model of medical tourism: Implications for future research. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allied Market Research. Medical Tourism Market by Treatment Type (Dental Treatment, Cosmetic Treatment, Cardiovascular Treatment, Orthopedic Treatment, Neurological Treatment, Cancer Treatment, Fertility Treatment, and Others): Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2019–2027. Available online: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/medical-tourism-market (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Horowitz, M.D.; Rosensweig, J.A.; Jones, C.A. Medical tourism: Globalization of the healthcare marketplace. Medscape Gen. Med. 2007, 9, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.A. Medical tourism and telemedicine: A new frontier of an old business. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awadzi, W.; Panda, D. Medical tourism: Globalization and the marketing of medical services. Consort. J. Hosp. Tour. 2006, 11, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J. Contemporary medical tourism: Conceptualisation, culture and commodification. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. Medical Tourism: Sea, Sun, Sand and … Surgery. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, F.; Soltani, S.; Tham, A. Medical tourism for COVID-19 post-crisis recovery? Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 32, 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, S. These Are the 4 Countries Offering COVID-19 Vaccines to Tourists. 2021. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/travel/2021/07/14/these-are-the-4-countries-offering-COVID-19-vaccines-to-tourists (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Smith, N.; Styllis, G. Vaccine Tourism Packages Allow Rich Asians to Visit US for Covid Jabs. 2021. Available online: https://www.traveller.com.au/vaccine-tourism-packages-allow-rich-asians-to-visit-us-for-covid-jabs-h1w64q (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Hoffower, H. Richer Countries Have Most Available Vaccine Doses as the Global Recovery Becomes K-Shaped. 2021. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/vaccine-wealth-gap-between-rich-poor-countries-administered-doses-2021-4 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- JapanTimes. The World’s Wealthiest Countries are Getting Vaccinated 25 Times Faster. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/04/09/world/vaccines-wealthy-countries/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Gordon, A.L.; Banjo, S.; Goldman, H. Vaccine Tourism Replaces Vacation Travel. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2021-01-21/vaccine-tourism-replaces-vacation-travel (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Block, D. An Unexpected Boon to America’s Vaccine Towns. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2021/04/vaccine-tourism-economic-boost-towns/618504/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Li, L. Vaccine Snob’ Travelers Head to Guam for Sun, Sea—And Shot. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/vaccine-tourism-guam-covid/2021/09/03/87d76158-09ef-11ec-a7c8-61bb7b3bf628_story.html (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Schengen Visa Info. These Countries Are Now Offering COVID-19 Vaccines for Tourists. Available online: https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/these-countries-are-now-offering-COVID-19-vaccines-for-tourists/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- UNWTO. Global Report on the Power of Youth Travel—Volume Thirteen. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284417162 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- UNWTO. Youth Travel Matters—Understanding the Global Phenomenon of Youth Travel. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284412396 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Yousaf, A.; Amin, I.; Santos, J.A.C. Tourist’s motivations to travel: A theoretical perspective on the existing literature. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Min, I.S.; Seo, B.J. A study among Chinese tourists in their 20s and 30s for determining their choice of medical tourism destinations. Int. J. U E Serv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. The Power of Youth Travel. Available online: http://www2.unwto.org/publication/am-reports-volume-2-power-youth-travel (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Veiga, C.; Santos, M.C.; Águas, P.; Santos, J.A.C. Are millennials transforming global tourism? Challenges for destinations and companies. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2017, 9, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.B.; Tavitiyaman, P. How young tourists are motivated: The role of destination personality. Tour. Anal. 2018, 23, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P.; Brochado, A.; Dimova, L. Millennials’ travel motivations and desired activities within destinations: A comparative study of the US and the UK. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2034–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S. When Middle East meets West: Understanding the motives and perceptions of young tourists from United Arab Emirates. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.G.; York, V.K.; Brannon, L.A. Travel for treatment: Students’ perspective on medical tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.L.; Frederick, J.R. Medical tourists: Who goes and what motivates them? Health Mark. Q. 2013, 30, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Confente, I.; Vigolo, V. Online travel behaviour across cohorts: The impact of social influences and attitude on hotel booking intention. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahli, A.B.; Legohérel, P. The tourism web acceptance model: A study of intention to book tourism products online. J. Vacat. Mark. 2016, 22, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaguru, R. Role of value for money and service quality on behavioural intention: A study of full service and low cost airlines. J. Air Transport. Manag. 2016, 53, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G.; El-Masry, A.A. Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, A.M.; Baláž, V. Tourism and trust: Theoretical reflections. J. Travel Res. 2020, 60, 1619–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, I.C.-H.; Cheung, C.-N.; Fu, K.-W.; Ip, P.; Tse, Z.T.H. Vaccine safety and social media in China. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2016, 44, 1194–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dinev, T.; Hart, P. An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce transactions. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, J.M.O.; González, M.V.R. Explaining physicians’ acceptance of EHCR systems: An extension of TAM with trust and risk factors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, M.A.; Sánchez, J.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Callarisa, L. Relationship quality with a travel agency: The influence of the postpurchase perceived value of a tourism package. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2007, 7, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, N.; Koo, C. The use of social media in travel information search. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszinski, R.; Marn, M.V. Setting value, not price. McKinsey Q. 1997, 1, 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J.P. Reliability: A review of psychometric basics and recent marketing practices. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Pang, C.; Liu, L.; Yen, D.C.; Tarn, J.M. Exploring consumer perceived risk and trust for online payments: An empirical study in China’s younger generation. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Tao, D.; Qu, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, R.; Zhang, W. The roles of initial trust and perceived risk in public’s acceptance of automated vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 98, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing (Advances in International Marketing, Volume 20); Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. Int. J. Strateg. Manag. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D.W. Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in “MIS Quarterly”. MIS Q. 2012, 36, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Method for Business Research; Marcoulides, G., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, T.T.; Sun, S. Exploring gender differences in Islamic mobile banking acceptance. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 14, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Esposito, V.V., Chin, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Petrick, J.F. The discriminant effect of perceived value on travel intention: Visitors versus nonvisitors of Florida Keys. Tour. Rev. Int. 2015, 19, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y. Value as a medical tourism driver. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 22, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Olya, H.G.T.; Han, H. Effect of general risk on trust, satisfaction, and recommendation intention for halal food. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Guo, Y.; Hu, D. Information framing effect on public’s intention to receive the COVID-19 vaccination in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawan, H.M.; Sondakh, O. How to enhance word of mouth in the era of e-commerce: Case study of Tokopedia. Int. J. Sci. Bus. 2020, 4, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R. Internet-based patient-physician electronic communication applications: Patient acceptance and trust. E-Serv. J. 2007, 5, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.-Y.; Tsai, J.C.-A.; Chuang, C.-C. Investigating primary health care nurses’ intention to use information technology: An empirical study in Taiwan. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, V.A.; Li, N.; Synder, J.; Dharamsi, S.; Benjaminy, S.; Jacob, K.J.; Illes, J. You don’t want to lose that trust that you’ve built with this patient: (Dis)trust, medical tourism, and the Canadian family physician-patient relationship. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: Profile of the Unvaccinated. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-COVID-19/poll-finding/kff-COVID-19-vaccine-monitor-profile-of-the-unvaccinated/ (accessed on 21 August 2021).

- Coad, J.E.; Shaw, K.L. Is children’s choice in health care rhetoric or reality? A scoping review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 64, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Sinha, N.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J. Determining factors in the adoption and recommendation of mobile wallet services in India: Analysis of the effect of innovativeness, stress to use and social influence. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 50, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Xu, J. Population aging, consumption budget allocation and sectoral growth. China Econ. Rev. 2014, 30, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, K.; Ractham, P.; Abrahams, A. Website development by nonprofit organizations in an emerging market: A case study of Thai websites. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2016, 21, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, K.; Abrahams, A.; Ractham, P. E-progression of nonprofit organization websites: US versus Thai charities. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2016, 56, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Ractham, P.; Kaewkitipong, L. The community-based model of using social media to share knowledge to combat crises. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chengdu, China, 24–28 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tim, Y.; Yang, L.; Pan, S.-L.; Kaewkitipong, L.; Ractham, P. The emergence of social media as boundary objects in crisis response: A collective action perspective. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Perea-Moreno, A.J.; Martinez-Jimenez, M.P.; Suarez-Varela Varo, I.; Vaquero-Abellánd, M. Social networks’ unnoticed influence on body image in Spanish university students. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.A.; Whitehill, J.M. Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Res. 2014, 36, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, C.; Ferguson, C.J.; Negy, C. Social media use and mental health among young adults. Psychiatr. Q. 2018, 89, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.R.; Zivich, P.N.; Frerichs, L. Social influences on obesity: Current knowledge, emerging methods, and directions for future research and practice. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larisa, I.F.; Gabriela, T. Medical tourism market trends-an exploratory research. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, Bucharest, Romania, 30–31 March 2017; pp. 1111–1121. [Google Scholar]

| Construct | Measurement Items | Adapted From |

|---|---|---|

| Intention to adopt vaccine tourism |

| [61] |

| Intention to recommend vaccine tourism |

| [61] |

| Trust in the foreign healthcare system |

| [76,77] |

| Social Influence |

| [61] |

| Price value |

| [61] |

| Respondents | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 133 | 74.30 |

| Male | 46 | 25.70 |

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 70 | 51.40 |

| 20–29 | 92 | 39.11 |

| 30–39 | 17 | 9.50 |

| Level of interest in vaccine tourism | ||

| Very interested | 13 | 7.26 |

| Somewhat interested | 79 | 44.13 |

| Neutral | 87 | 48.60 |

| Social media use to learn about vaccine tourism | ||

| 0 to 3 months | 119 | 66.48 |

| 3 to 6 months | 44 | 24.58 |

| 6 to 12 months | 16 | 8.94 |

| Vaccine tourism destination preference | ||

| USA | 147 | 82.12 |

| UK | 13 | 7.26 |

| South Korea | 6 | 3.35 |

| Singapore | 5 | 2.79 |

| Others | 8 | 4.47 |

| Spending budget for the vaccine tourism package (USD$) | ||

| Less than 1000 | 39 | 21.79 |

| 1000–2000 | 86 | 48.04 |

| 2000–3000 | 43 | 24.02 |

| 3000–4000 | 10 | 5.59 |

| More than 4000 | 4 | 0.56 |

| The length of vaccine tourism (days) | ||

| 2–8 | 33 | 18.44 |

| 9–15 | 71 | 39.66 |

| 16–22 | 28 | 15.64 |

| 23–29 | 19 | 10.61 |

| Longer than 29 | 28 | 15.64 |

| Vaccine preference | ||

| Pfizer-BNT | 116 | 64.80 |

| Johnson & Johnson | 39 | 21.79 |

| Moderna | 21 | 11.73 |

| Sinovac | 1 | 0.56 |

| Sputnik V | 1 | 0.56 |

| AstraZeneca | 1 | 0.56 |

| Constructs | Mean | Standard Deviation | Composite Reliability | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price value (PV) | 5.20 | 1.46 | 0.9432 | 0.9095 | 0.8471 |

| Social influence (SI) | 5.52 | 1.37 | 0.8943 | 0.8223 | 0.7385 |

| Intention to adopt vaccine tourism (INT) | 4.65 | 1.44 | 0.9617 | 0.9402 | 0.8933 |

| Intention to recommend vaccine tourism (REC) | 5.76 | 1.24 | 0.9641 | 0.9503 | 0.8703 |

| Trust in foreign healthcare system (TST) | 6.25 | 1.03 | 0.9223 | 0.8736 | 0.7983 |

| PV | SI | INT | REC | TST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV | 0.9204 | ||||

| SI | 0.3647 | 0.8594 | |||

| INT | 0.4364 | 0.2512 | 0.9451 | ||

| REC | 0.4679 | 0.4506 | 0.5103 | 0.9329 | |

| TST | 0.3572 | 0.3089 | 0.2195 | 0.4704 | 0.8935 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Path Coefficients | T-Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| H1a. TST → INT | 0.053 | 0.696 |

| H2a. SI → INT | 0.095 | 1.166 |

| H3a. PV → INT *** | 0.383 | 4.908 |

| H1b. TST → REC ** | 0.294 | 3.868 |

| H2b. SI → REC ** | 0.262 | 3.154 |

| H3b. PV → REC *** | 0.267 | 3.019 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaewkitipong, L.; Chen, C.; Ractham, P. Examining Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Tourism for International Tourists. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212867

Kaewkitipong L, Chen C, Ractham P. Examining Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Tourism for International Tourists. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212867

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaewkitipong, Laddawan, Charlie Chen, and Peter Ractham. 2021. "Examining Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Tourism for International Tourists" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212867

APA StyleKaewkitipong, L., Chen, C., & Ractham, P. (2021). Examining Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine Tourism for International Tourists. Sustainability, 13(22), 12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212867