1. Introduction

A shift from traditionally invested assets to socially responsible investing (SRI), broadly defined as the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into investment practices, is a crucial driver of sustainable development [

1]. Millionaires and billionaires, i.e., private high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), hold a vital role in this shift. The United Nations calculated that investments of USD2.5 trillion per year are missing to finance sustainable development [

2]. Thereby, the wealthy top 1% of the world’s population controls about USD 191.6 trillion as of 2020, nearly half of global wealth [

3]. It is crucial to understand the investment behaviors of HNWIs to mobilize this substantial source of capital for sustainable development.

To understand whether private investors engage in SRI, the literature tends to put a higher emphasis on proving the financial profitability of SRI (see [

4,

5,

6]) than, for example, its positive impact on social welfare [

7,

8]. However, since SRI brings together financial profits and social welfare, sustainable investing goes well beyond the question of whether or not SRI is more profitable than traditional investing [

6,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Still, many investors are attracted to SRI due to social welfare reasons (e.g., [

14,

15,

16]). Consequently, the profitability debate around SRI only partially solves the issue of knowing little about sustainable investors [

16,

17] and SRI-oriented HNWIs [

18,

19]. To gain deeper insight into the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs, we need to understand their individual dealings with both social welfare issues and financial gains in their SRI investments.

A reference group theory perspective suggests that the individual investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs is fundamentally influenced by the groups for which the wealthy private investor has a membership. The reference group theory operates on the principle that individuals always orient themselves to others, as their attitudes, values, and self-appraisals are shaped by their identification with and comparison to reference groups [

20]. To establish or maintain individual identification with the reference group, individuals behave, believe, and perceive as the group does [

21]. There are two types of reference groups [

22,

23,

24]. Normative reference groups establish and enforce specific standards which can be considered as norms. Comparative reference groups serve individuals as a point of reference in making evaluations or comparisons without the evaluation of the individual by others in the reference group [

23].

Hence, from a reference group theory perspective, SRI-oriented HNWIs’ identification with and comparison to a respective reference group significantly influences whether, how, and to what extent they bring together financial profits and social welfare in their investments. Thus, while the influence of normative and comparative reference groups is central to our understanding of the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs, previous research has not yet addressed this issue. Consequently, our knowledge of HNWIs committed to SRI remains underdeveloped. The main objective of our study is to develop this knowledge, and we thus ask: how do reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs?

To answer this question, we adopt a qualitative research strategy. Such a strategy is advantageous for developing our knowledge of the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs because qualitative research supports the generation of novel insights “at a level of detail and nuance that can be difficult or impossible to achieve using only quantitative methods” [

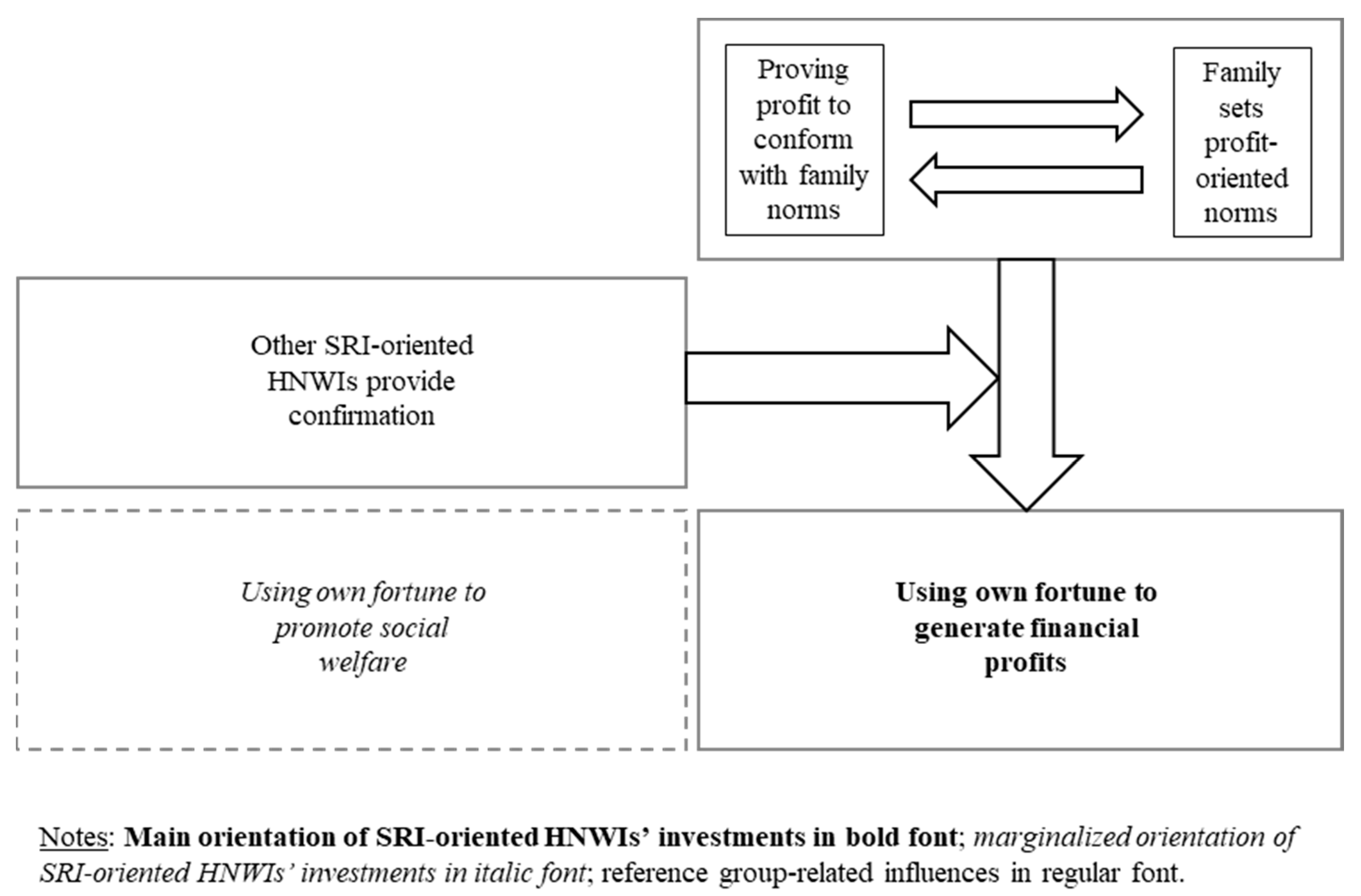

25] (p. 637). We conducted semi-structured interviews with 42 SRI-oriented HNWIs and 13 experts who consult with them and closely monitor the SRI market. Based on our analysis of this unique empirical data, we develop a framework to explain how different reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. Our framework indicates that, on the one hand, the family serves as a normative reference group that holds up economic profit striving and directly influences HNWIs towards generating financial profits in their investments at the expense of social welfare considerations. On the other hand, fellow SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a comparative reference group that places little emphasis on accountability for social issues and indirectly influences SRI-oriented HNWIs to subordinate social welfare issues to financial gain.

Our research makes two contributions to the literature. First, we add to SRI research by providing insights into the hitherto little-researched SRI engagement of wealthy private investors (e.g., [

16]). Our framework explains that SRI-oriented HNWIs prioritize financial gains at the expense of social welfare because they are encouraged by reference groups to use their wealth to achieve economic profits, even though they already have immense wealth. Second, we contribute to reference group theory, which suggests different reference groups based on differentiating between a normative and a comparative function of a reference group (e.g., [

23]). We show that normative and comparative reference groups can coexist but that the normative reference group suppresses the comparative reference group in conflict. This finding implies different spheres of influence of normative and comparative reference groups.

We proceed by presenting existing SRI research on HNWIs and, on this basis, problematizing the lack of knowledge on the influence of reference groups on the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. We then outline our research context and method and present the results of our study. On this basis, we develop a framework of how reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. We finish by discussing the implications for the literature, some practical implications, the limitations of our study, avenues for further research, and a conclusion.

4. Findings

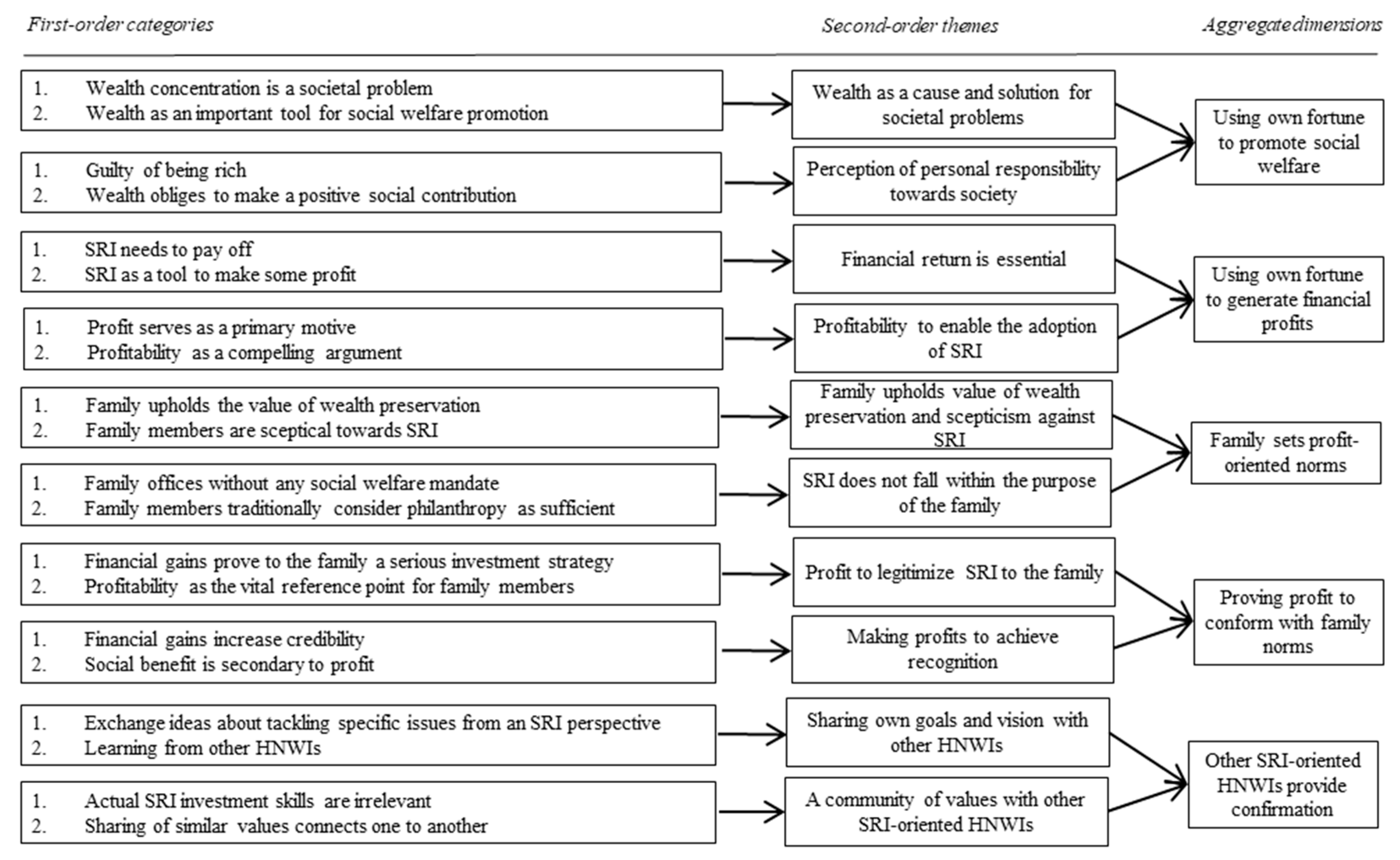

We structure the empirical results as follows: first, we outline how HNWIs use their own fortunes to promote social welfare. Second, we show that they use their fortunes to generate financial profits. Third, we depict how the family sets profit-oriented norms. Fourth, we demonstrate that SRI-oriented HNWIs engage in proving profit to conform with family norms. Finally, we present how other SRI-oriented HNWIs provide confirmation.

4.1. Using Own Fortune to Promote Social Welfare

When asked about their motives for SRI, HNWIs often pointed out that they strive to use their fortune to promote social welfare. In the following, we will discuss two aspects of our data supporting this insight.

Wealth as a cause and solution for societal problems. Wealth has an essential role in society in that it functions equally as a cause of and solution to societal problems such as inequality. Firstly, many HNWIs describe wealth as the cause by pointing out that wealth concentration is a societal problem. One informant (HNWI 12), for example, problematizes wealth concentration by arguing that “wealth distribution is definitely something that I adhere to” in my investment decisions because “I just feel like opportunities are a little bit skewed at this point.” Further, the wealth owner problematizes wealth concentration by contrasting it with an equal society that is much more beneficial for all involved, as it ensures equal opportunities, i.e., “a much more balanced society is extremely beneficial for all”.

Secondly, HNWIs emphasize that ample financial resources may serve to tackle social problems. One wealth owner (HNWI 16) illustrates wealth as an important tool for social welfare promotion by the example of an investment strategy aimed at combating climate change and all its resulting societal consequences. According to this informant, investing wealth through this strategy serves “to bend emissions and create opportunities to generate land that we are able to move back towards a healthy planet.” In this regard, the strategy goes far beyond combating climate change by securing that “people are going to be less hungry, be better fed, have better sanitation, and all those things that potentially come with making better use of the resources we have”.

In sum, our empirical analysis of the interview data shows that HNWIs see wealth as both a cause of and an opportunity to solve societal problems. On the one hand, HNWIs localize the concentration of wealth as the cause of the unfair distribution of opportunities in society; on the other hand, they describe wealth as the central means of solving current social problems, such as the unfair distribution of resources. In

Table 2, we provide further evidence of wealth as a cause and solution for societal problems.

Perception of personal responsibility towards society. The interviewed HNWIs deal in detail with the connection between wealth and the potential responsibility that comes with it and how this very connection affects them personally. Firstly, HNWIs often mentioned the issue of being guilty of being rich. For example, after being asked by the interviewer about the fairness debate around inherited wealth and first-generation wealth and how the respective generation and the family as a whole deal with this debate, one informant (HNWI 2) responded that “we know [about the fairness debate around inherited wealth], and it’s something that my mom, I think, makes a big effort of reminding us about.” Furthermore, the informant explicitly points out the feelings of guilt that come along with being wealthy: “but yes, I do think there’s a big element of unfairness there”.

Secondly, our data on HNWIs suggest that wealth obliges one to make a positive social contribution. The interviewees clearly express a personal desire to do something about the inequality in today’s world and the lack of social mobility. This includes straightforward measures such as the intention to redistribute financial resources but also to use one’s own capital to promote projects that increase social mobility. One wealth owner (HNWI 25) clarifies this further by pointing out that “there’s this fundamental discomfort with the inequality that exists in the world” and that driving the investment of wealth “at the portfolio level but also the deal level is this sense of how can we create more equality in the world”.

To summarize, the interviewed HNWIs see themselves, primarily because of their wealth, as bearing a personal responsibility to society. This sense of personal responsibility is based both on feelings of guilt, which originate from their own wealth, and on the conviction that wealth obliges one to solve social problems such as the increasing inequality between the rich and the poor. In

Table 3, we provide further evidence of the perception of personal responsibility towards society.

4.2. Using Own Fortune to Generate Financial Profits

The interviewed SRI-oriented HNWIs expressed that they aim to use their own fortune for generating financial profits, as evidenced by the profit orientation of their sustainable investment activities. We found two aspects supporting this insight that we will detail in the following.

Financial return is essential. HNWIs generally regard SRI as a financial instrument that not only has a positive social impact but also generates an economic return. Firstly, this circumstance is shown by the aspect that SRI needs to pay off. One wealth owner (HNWI 34) illustrates the importance of making money with SRI by the example of impact investing, which can be understood as a synonym of SRI. This informant notes that people “confuse it [impact investing] with philanthropy” while instead “impact investing is about making a positive impact and make a lot of money”.

Secondly, HNWIs often consider their sustainable investing activities as a way of making a financial profit. Hence, wealthy sustainable investors see SRI as a tool to make some profit. For example, the following informant (HNWI 1) clarifies the importance of earning money as follows: “The argument is that we don’t want to lose money [with SRI]. We don’t want this to be an expense. We want to earn money, make investments that are profitable”.

In conclusion, our analysis indicates that the interviewed HNWIs conceive SRI as an investment vehicle to contribute to society and generate financial profits. In each case, financial gain is emphasized, for example, when HNWIs point out that SRI should help “make a lot of money” and serve as a tool to generate a financial surplus. In

Table 4, we provide further evidence that financial return is essential.

Profitability to enable the adoption of SRI. Profitability has often been expressed under the umbrella of building the field of sustainable investing. Many wealthy private investors mention the need to prove the established idea that SRI should be as equally profitable as traditional investments. This is, firstly, because HNWIs suggest that profit serves as a primary motive. One wealth owner (HNWI 31) points out that “the thesis of impact investing is that you can achieve the same returns.” Moreover, the informant states that the confirmation of this thesis is critical for whether investors go into impact investing at all: “at the performance of portfolios, there’s very little evidence. (…) If you say that to people, they’ll be like, ‘hell no, I’m not putting that money into impact’”.

Secondly, the interviewed SRI-oriented HNWIs consider profitability as a compelling argument to encourage the adoption of sustainable investment practices by third parties. One interviewed HNWI (HNWI 32) explains this by the case of convincing the board of their own family office to adopt SRI: “I had to look at it from the perspective of where can I get some wins, where can I get the leverage going. And it’s honestly just about proving that we can make market returns or better”.

In sum, the analysis of the interview data suggests that HNWIs consider the financial profitability of SRI relevant for establishing the field of sustainable investing and for promoting its adoption among wealthy private investors in particular. This insight is grounded on the circumstances that profit motives dominate the investment behavior of HNWIs and that profitability is the most compelling argument for adopting SRI or not. In

Table 5, we provide further evidence of profitability to enable the adoption of SRI.

4.3. Family Sets Profit-Oriented Norms

Families and their members who surround the HNWIs set profit-oriented norms that the wealthy sustainable investors interviewed perceive as standards and expectations they must adhere to. Below, we detail two aspects of the insight that families demand financial profit and claim this demand toward SRI-oriented HNWIs.

Family upholds the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI. HNWIs repeatedly mention the relevance of their family members for their investments. Firstly, their family upholds the value of wealth preservation that is an essential guideline for them. Our data suggest, at least in the context of investing, that wealth preservation is the most prominent value in wealthy families. For example, in response to whether there are any particular values or principles regarding financial investments that the HNWI has adopted from their own family, the informant (HNWI 15) mentions values related to “wealth preservation” that many wealthy families have to “set up expectations for family members in order to access funds”.

Secondly, the interviewed HNWIs repeatedly point out that family members are skeptical towards SRI. Families are often unfamiliar with the underlying idea of SRI, of combining financial investment with a positive social and environmental contribution, and therefore cannot imagine how this would work. One wealth owner (HNWI 8) further explicates this skepticism by “an added level of skepticism that the family office brings whenever we put forth something with the knowledge that it is impact.” This informant locates this skepticism in the technical terms and expressions associated with impact investing, as “they (family office members) themselves put an added level of skepticism on the investments we put forward because of the impact investment terminology”.

In conclusion, our informants emphasize that their families uphold the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI. On the one hand, such wealth preservation provides the interviewed HNWIs with a basis for their value formation and presents a critical normative framework against which they align their investment behavior. On the other hand, families are skeptical about SRI and the associated sustainable investment behaviors because, according to the HNWIs interviewed, their family members are often unacquainted with SRI. In

Table 6, we provide further evidence of the issue that the family upholds the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI.

SRI does not fall within the purpose of the family. HNWIs themselves often face the circumstance that their family does not see the point of linking their financial investments to socially and environmentally positive contributions. Firstly, this circumstance can be explained by the fact that there usually are family offices without any social welfare mandate. The following statement by a wealth owner (HNWI 15) illustrates that most family offices lack any mandate for making a positive social or environmental contribution as part of their investment activities: “I know many family offices, and I always ask if they have an impact mandate or something, and a lot of them still don’t”.

Secondly, SRI-oriented HNWIs mentioned that their families often uphold that they already are engaged in philanthropic activities and therefore do not see any need for SRI. Hence, family members traditionally consider philanthropy as sufficient. The extent to which this very attitude can hinder SRI illuminates an informant (HNWI 6) who is appropriately committed to such investments outside the family and its wealth because family members only focus on philanthropy, as explicated by the family foundation: “they (family members) have a very traditional sort of foundation setting. (…) So the foundation is purely about giving philanthropic capital, not capital but the income generated from it”.

To sum up, the analysis points towards the circumstance that HNWIs’ families do not see why striving for financial returns should link to a positive societal contribution. This insight reflects the fact that family offices, officially entrusted with managing the family’s assets, traditionally do not have a social welfare mandate. Moreover, the circumstance that family members traditionally consider philanthropy to be sufficient, where any economic activity is usually separated from social welfare engagement, supports the insight that SRI does not fall under their families’ purpose. In

Table 7, we provide further evidence that SRI does not fall within the purpose of the family.

4.4. Proving Profit to Conform with Family Norms

Our data shows that HNWIs are engaged in proving the economic profitability of SRI to conform with family norms, suggesting that a “good” investor is an economically successful investor. This, however, differs from the above-described striving for financial return in that HNWIs primarily aim for economic profit to prove their conformity with family norms. We detail the two aspects related to this insight below.

Profit to legitimize SRI to the family. HNWIs often mention financial success as a source of legitimacy. Firstly, the informants said that financial gains prove to the family a serious investment strategy. For example, an interviewed HNWI (HNWI 15) explicates how generating financial returns built the necessary approval from the family hedge fund for adopting an SRI strategy: “my hedge fund, this email I got was, ‘oh it (SRI) sounds just like charities, and no problem, you can be on the board’”. However, this wealth owner seeks to demonstrate that SRI is not charity, but allows for the generation of financial gains, to convince family members that SRI is a serious investment strategy: “they (members of the family hedge fund) approached me to be on the board, but it’s actually not okay like I want people to realize that it can be very profitable, and it is important for me to generate returns so that again you can prove this concept”.

Secondly, our interview partners render financial return and the proof of profitability as the vital reference point for family members and a known and appreciated measure for assessing individuals within the family. Suppose the individual HNWI can provide evidence that an investment decision generates enough profit. In that case, influential family members, such as the grandfather, acknowledge this as sufficient to let the individual (i.e., in our example here, the grandchild) proceed with their own ideas. It thus justifies the position of a capable, independent decision-maker. This is illustrated in the following statement by a wealth owner (HNWI): “I decided to talk to my grandfather, and I told him that I wanted to work with education and that it was something that would change the world. The only thing that he said was, ‘but how are you going to pay your bills?’”.

In a nutshell, the interviewed HNWIs indicate that they use financial success as a source for legitimizing SRI to their family members. This approach is explained on the one hand by the circumstance that HNWIs draw on economic profits to prove a serious investment strategy; for example, to receive approval from their family hedge fund for adopting an SRI strategy. On the other hand, financial success is the vital reference point for assessing family members and thus for whether an individual family is considered appropriately competent to invest the family capital in SRI. In

Table 8, we provide further evidence of financial success as a means of legitimization within the family.

Making profits to achieve recognition. SRI-oriented HNWIs strive to gain recognition as investors, for example, from their families, by making financial profits. Firstly, next-generation wealth owners born into their societal position point out that they need to find ways to show that their actions are credible. A ubiquitous way to achieve this goal is profit because financial gains increase credibility. One interviewed HNWI (HNWI 5) describes the importance of bringing proof to the family as a financially successful investor using the following comparison: “you’re expected to shape your life so that you can become a good steward (of your inherited wealth), versus, ‘oh I have this, great, I just found out, so I don’t have to work as hard, I don’t have to find a job, I can just rely on my family’”. Thus, recognition in the family is obtained by distinguishing oneself as a financially successful steward of inherited wealth.

Secondly, because wealthy sustainable investors often consider making profits essential for achieving recognition, they usually suggest that the social benefit is secondary to profit. HNWIs often do not show their ambition to prove the impact case of SRI to meet the initial intention of a social or environmental purpose. One interviewed HNWI (HNWI 31) illustrates this by pointing out that the measurement of any positive social or environmental impact merely distracts from the central goal of making a financial profit: “this whole discussion about impact measurement, I think, is diverting maybe too much resources from thinking about how to make this financial success first”. Hence, in the case of SRI engagement, the social benefit is systematically subordinated to financial profit.

In summary, our analysis of the interview data suggests that SRI-oriented HNWIs strive to gain recognition as investors from their family members by making financial profits. This insight is evidenced first by HNWIs aligning their investments primarily with financial performance to make their actions more credible, and second by making the measurement of any positive societal impact secondary to proving financial performance. In

Table 9, we provide further evidence for the role of making profits to achieve recognition.

4.5. Other SRI-Oriented HNWIs Provide Confirmation

The HNWIs in our data frequently pointed out other SRI-oriented HNWIs whom they admire and who serve as a reference for them. We detail two aspects related to this insight in the following.

Sharing one’s own goals and vision with other HNWIs. Our informants often praise the community of other SRI-oriented HNWIs and how they thrive on being surrounded by like-minded private investors who share their goals and visions. Firstly, other SRI-oriented HNWIs are necessary for a wealthy sustainable investor to exchange ideas about tackling specific issues from an SRI perspective. An investment advisor (Expert 12) who regularly consults with HNWIs further elaborates on this very issue by pointing out the relevance of “a community of like-minded investors”. Such a community allows SRI-oriented HNWIs “to deep-dive into a specific issue area” and how to “tackle that from a sustainable investing standpoint”.

Secondly, our informants frequently emphasize the importance of learning from other HNWIs. One HNWI (HNWI 25) explains the importance of learning from others in the context of a global network of impact investors as “being part of a more global community of impact investors was extremely helpful.” According to the informant, this worldwide network of SRI-oriented HNWIs derives its importance, particularly in representing a community, “from that you can learn”.

To sum up, the interviewed HNWIs point out the relevance of sharing their goals and visions with other SRI-oriented wealthy private investors. This relevance stems from the fact that like-minded investors provide an individual HNWI with the opportunity to share ideas on approaching specific issues from an SRI perspective and learn more about SRI from other HNWIs. In

Table 10, we provide further evidence for the role of sharing one’s own goals and vision with other HNWIs.

A community of values with other SRI-oriented HNWIs. In contrast to their families, other HNWIs do not demand anything from our informants. While family members claim their demands for a financial profit, other SRI-oriented HNWIs do not make any demands, either in terms of economic gain or contribution to social welfare. Firstly, this becomes evident by the circumstance that actual SRI investment skills are irrelevant to participation. One wealth owner (HNWI 26) accordingly points out that every HNWI is welcome to the community of SRI-oriented HNWIs regardless of where the person is on the SRI journey: “it’s very nice to be welcomed by a group that says, ‘if you want us to support you on your journey,’ that term is used a lot, the impact journey that we’re on here”. Thereby, it is more about experiencing the journey toward making a positive social impact with a group of like-minded SRI-oriented HNWIs than actually about achieving the goal of creating a positive impact. “I don’t feel as pressed to come up with something perfect, but rather to have a full journey with a group of like-minded individuals” (HNWI 26).

Secondly, our informants frequently mentioned that sharing similar values connects one to another. One informant (HNWI 10) clarifies the importance of being surrounded by like-minded HNWIs who share the same goals and visions and how such a community serves as a source for inspiration and support because “you will feel alone, and also, you will not be able to scale if you are alone (…). And here comes a certain belief, that of conviction.” The shared set of values among SRI-oriented HNWIs creates a sense of community, which is a crucial source of guidance for the individual wealth owner. In fact, according to the same informant, “it’s always important to be a part of a community that you share with a grandiose ambition”.

In conclusion, our analysis of the interview data indicates that other SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a community of values that does not impose concrete requirements on an individual HNWI, neither in terms of financial gain nor of positive social impact. Namely, on the one hand, whether an individual HNWI has SRI skills and thus actual knowledge of how to link economic and social aspects is irrelevant to belonging to the community of SRI-oriented HNWIs. On the other hand, as a community of values that does not impose any concrete requirements on an individual HNWI, it is mainly about sharing the same goals and visions. In

Table 11, we provide further evidence of a community of values with other SRI-oriented HNWIs.