Abstract

This research aims to explore the relationships between gender, educational attainment, and job quality, including work autonomy, work intensity, and job satisfaction across Germany, Sweden, and the UK. The European Working Conditions Survey 2015 was used to achieve this research objective. Descriptive statistics and multivariate regression analysis were used to determine how educational level plays an important role in creating gender differences in job quality across three countries. The findings show that receiving postsecondary education can improve work autonomy for both German and Swedish women. However, postsecondary education has different impacts on gender gaps in job quality in these countries. While postsecondary education lowers the gender gap in work autonomy and intensity in Sweden, postsecondary education increases the gender gap in work autonomy and intensity in Germany. Postsecondary education does not significantly decrease gender differences in job satisfaction in Germany or Sweden or any of our job quality measures in the UK. These findings challenge the commonly held belief that higher education has a positive effect on job quality. In fact, gender norms and national institutional factors may also play important roles in this relationship.

1. Introduction

Women constitute half of the labor force in most European countries, yet differences in compensation still exist between women and men [1]. More importantly, individuals often pay more attention to job quality rather to compensation alone. Job quality also differs between genders, which is, nevertheless, often ignored in extant research. This study on job quality between women and men is driven by the objective of sustainable and equitable development in the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development Agenda 21. Aside from promoting equal access to education, occupation, and health, the United Nations also highlights the significance of improving women’s participation in economic and political decision making to keep with their freedom and dignity [2].

The present study seeks to explore the relationships between gender, education, and job quality in Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom (UK) using Esping-Anderson’s (1990) welfare capitalism theory. According to Esping-Anderson (1990) [3], countries can be classified into three different types of welfare states according to their institutional and ideological differences. Germany, Sweden, and the UK represent three different kinds of models. Germany represents a corporatist state, which is classified as the “strong male breadwinner” model. Within this model, the man in a nuclear family takes the lead role in the labor market, while the woman takes care of the family and domestic labor at home. Sweden is characterized by a “weak male breadwinner” model, which corresponds to the social-democratic state. In Sweden, policies encourage all citizens to participate in the labor market and family responsibilities regardless of their gender. The UK represents a neoliberal state with low gender equity. Its main feature is that it is market-driven, which is integral to the neo-liberal market agenda [4]. Variations between these three countries show that gender differences are socially constructed in distinct institutional contexts [5]. However, previous research rarely addresses how institutional contexts shape the relationships between gender, education, and job quality. This study asks, “To what extent does job quality differ across gender, including work intensity, work autonomy, and job satisfaction in terms of institutional regimes?” In its second research question, it further explores the question, “How does higher education affect the gender gap in job quality across contexts?” This paper will focus on these two questions to help us better understand gender inequality in job experience across contexts. Thus, we propose a three-way interaction between gender, education, and country regimes in shaping employees’ job quality. To examine our hypothesis, data from the 5th European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS) were analyzed.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Defining Job Quality

Researchers have varying perspectives and indicators on how to measure job quality. The quality of jobs is an important indicator because it shows the fundamental characteristics of the job [6]. Following the literature on job quality and occupational structure, we focus on work intensity, work autonomy, and job satisfaction in this paper. Work intensity is defined as the physical, cognitive, and emotional impact of a job on a human being [5]. Work autonomy refers to the employee’s freedom to make decisions about work activities [7]. To have autonomy at work means that the activity has an element of freedom, and employers treat employees like human beings rather than machines. Job satisfaction refers to the employee’s subjective satisfaction with their attitude towards the work, payment, and career advancement [8,9]. As job autonomy increases, job satisfaction also increases [10].

2.2. Gender and Working Conditions

For individuals, paid work, domestic work, care, and further education all require a serious time investment. Many women, especially after having children, choose to care for their families, which demands a great deal of their time. Some women then choose to switch to part-time positions, so they can have time for caring for their families but still participate in the labor market. However, these dual commitments may have negative effects on their careers. According to Gambles et al. (2006) [11], an ideal worker can fully dedicate themselves to their work and has no outside obligations or commitments. They are expected to adapt their lifestyle to the market demands. Thus, non-ideal workers are people who cannot fully dedicate themselves to their work. Women are classified in this category because they need time for their families, care activities, or any social commitments. When a woman has a newborn child or is obliged to take care of their children, they sometimes choose to leave the labor market for maternity leave, while others reduce their working hours during the period of childbirth or child-raising. They might lose their full-time status in the company that employs them. In addition, women suffer because when they become part-time workers, their wages are reduced, and they become marginal to the company, losing the possibility to have any further training opportunities for their long-term careers. Part-timers accumulate disadvantages over the long term [1]. Furthermore, women having family-care duties outside of their workplace creates difficulties in their advancing in a company’s hierarchy and working in leadership positions [4]. Only those women who fully remain in the labor market and continue to work in their companies can have similar benefits and status as men [5]. From an employer’s perspective, since the market is always fluctuating, there is usually a benefit to having flexibility around employee hiring. Companies may hire some part-timers when they need more labor to respond to increased demand for services or goods. When this need subsides, they maintain the full-time staff but make the part-time staff redundant or terminate their contracts. Government policies also influence this mechanism. Some countries subsidize part-time employment through reductions in social security costs, which may encourage employers to create temporary part-time jobs [1]. Lastly, regarding wellbeing, evidence shows that when people work more than 40 h a week, their well-being is lower than those actively working below 40 h [5].

Women tend to choose jobs that are compatible with combining their work with maintaining their roles as mothers and homemakers [12]. When it is unclear whether an employee has demonstrated sustained participation in the labor market, employers may be reluctant to invest in them. Therefore, when women get married and start to have children, they have an increased likelihood of employment interruption. Some women prefer to work part-time so that they can spend more time taking care of their children. Smith et al. (2013) [5] found that the proportion of women in part-time jobs, such as personal care, cleaning, and personal service, is higher than the proportion of men in these part-time jobs [5]. Gender differences can be seen in part-time work, where women dominate in comparison to men [13]. A recent study used responses related to work-life balance from several cycles of the Canadian General Social Survey and found that women in management and education have a lower work-life balance satisfaction than men [14], suggesting that women struggle more to balance family, work, and life responsibilities. Another study [15] using the European Social Survey found that women tend to report higher job satisfaction than men in some countries. Moreover, the gender wage gap varies across educational categories. Evidence shows that the gender wage gap is larger among highly educated individuals [16,17] but smaller among graduates holding a prestigious “career-signaling” degree, like economics, law, or engineering [18]. Given the inconsistent findings, whether there exists an interactional effect between gender and education on employment and job quality is still an unsolved question.

2.3. Variance across Country Regimes

In some industrialized societies, women who stay employed uninterruptedly have similar career patterns to men [13]. Other research reveals that men have higher levels of job complexity, autonomy, participation, and more promotion opportunities when compared to women. Women have fewer job rewards, work under different working conditions, and possess slightly different work values than men [19]. A recent research study used Balanced Worth Vector (BWV) to uncover the gender-job satisfaction paradox. The result showed that there is a substantial gender difference across countries, but the gender differences decrease over time [20]. The extent of the gender gap in job quality also differs between gender-egalitarian societies [12].

This study adopts the framework of different typologies of welfare states to investigate and compare the relationships between gender, education, and job quality. Germany represents a corporatist model, which is classified as a “strong male breadwinner” model. The taxation system, employment, and childcare policies all show that they favor women not to work after getting married and having children. This shows that the major role of women in Germany is to take care of the family, where there is a strong tradition in which the division of labor between husband and wife is separated [21]. However, this situation is gradually changing. There are now a few employee-friendly workplace measures focusing on women although these are few. After the parental leave legislation was reformed, the new state policy permits fathers to take parental leave to take care of their newborn children. This has raised gender equality [22].

In Sweden, however, policies encourage all citizens to participate in the labor market regardless of gender differences. Swedish women’s duties go beyond family responsibilities. Sweden has a “weak male breadwinner” model that represents the social-democratic state. The state provides parental leave and childcare through direct public provision. Since it focuses on providing all citizens with their universal rights regardless of gender, the percentage of women working in the public sector is high. In the UK, each family has the responsibility to pay for childcare or provide care themselves. There is no difference between whether the state provides the care service or individuals rely on their own resources because this is a private consumption choice. If a family wants to outsource its care, they can choose from informal childcare arrangements or the use of private daycare centers [1]. Given those differences in the welfare policies across three country regimes, this study explores the impact of the gender gap in job quality and whether different levels of education moderate this relationship.

2.4. Educational Systems

A nation’s competitiveness in today’s global economy is highly related to its citizens’ education levels and skills. An individual’s education level is relevant to how they adapt to new technologies and reform production systems [1]. The development of different skills in the workforce can lead to a new production system. An individual’s educational background can determine the autonomy they receive in a job. High levels of autonomy require correspondingly high levels of personal and cognitive skills [6]. Green’s perspective supports the relationship between job autonomy and an individual’s education level. Therefore, each country’s core question has become how to develop skills for young people who enter the labor market [1].

Across different nations’ education systems, there are varying degrees of standardization and stratification. Standardization refers to how closely the educational quality of each school across the entire country follows the same standard. A stratified educational system filters individuals into various distinctive categories, including traditional education or vocational training, and then sends them into the labor market [23,24]. Findings from Allmendinger’s (1989) [25] study show that if a person is educated in a stratified system, their occupational status is strongly determined by their educational attainment. The relationship between educational qualification and occupational status is less strong in unstratified systems. If a person is educated in a standardized system, they tend to change jobs less frequently than does someone educated in an unstandardized system.

For context, a brief introduction to Germany, Sweden, and the UK’s educational systems is provided as follows. Germany’s education system is highly standardized and stratified [25]. When children reach around age ten to twelve (after 4th grade), they progress through three different tracks, including the lower secondary school, middle school, and upper secondary school [26]. Each track leads to different types of education certificates. Only the last track can lead them to attend university. Students studying at vocational schools engage in vocational training and apprenticeships. The apprenticeship consists of part-time, school-based education and on-the-job training through work experience. The students can then use what they learn at school in the workplace. The design of apprenticeships is coordinated by three parties: unions, employer organizations, and state institutions. Tertiary education is provided by the state, is free of charge, and is not differentiated by quality or status. The link between the education system and employment position is close and strong [27]. The German system of vocational training is seen as an effective way to transfer young people from school to the labor market [1].

Regarding the UK’s educational system, it follows a market-driven approach to training that has elements of the traditional occupational labor market system [1]. Compulsory education lasts a minimum of eleven years. The vocational training system there is heterogeneous. The education of the vocational system can be characterized as being weakly stratified and more flexible than the German system because students are usually selected at a later age compared to when such selection occurs for students in Germany. It is, therefore, easier to switch between the academic and vocational tracks. The degree of standardization is low, and vocational UK qualifications are under-standardized [28,29].

Sweden’s educational system is a model of compulsory education that consists of nine years of education. Children start school from the age of seven. After students finish their compulsory education, they may continue academic education or vocational education. There are three subject tests: Swedish, English, and mathematics, which students must pass if they want to study in academic national programs. To graduate from upper secondary school requires passing nine additional subjects. For students who choose to study vocational courses, they are required to pass an additional five vocational subjects [30].

2.5. Education Attainment and Job Quality

Education has a robust influence on an individual’s labor market prospects [31]. At the most basic level, individuals acquire literacy and numeracy skills through the educational process. From a human capital theory perspective, the knowledge and skills training that schools provide is valuable in the job market. Individuals who successfully acquire marketable skills raise their performance [24,26]. Education helps people increase their earnings. Relevant research shows that literacy and numeracy skills are strongly associated with individuals’ labor market outcomes. Individuals with high levels of cognitive and academic skills earn more [32]. Highly educated individuals have higher salaries, superior occupational ranks, better employment contracts, and a higher probability of being employed than individuals with lower levels of qualification. Thus, education produces skills that are rewarded by employers [31].

The difference between compulsory education graduates (high school degree) and higher education graduates (college degree or above) is that the educational capital that the latter receives helps them to secure a more privileged position in the job market [33]. Individuals invest in their education, and later, their employer benefits from the productivity of a highly skilled worker. There is a relationship between educational credentials and employability. People with higher educational qualifications have improved chances of finding employment. This pattern can be found in European countries with some variation. Master’s degree graduates are not only successful in finding employment, but their search period is shown to be shorter than for people with lower educational qualifications. Furthermore, the positions they find are more closely related to their degrees and majors. This pattern applies in varying degrees of intensity to many European countries [34]. From the discussion above, we can see that educational qualifications might be directly related to the extrinsic outcomes of employment, such as earnings, but they might vary by different country regimes and over time.

There are several studies investigating the relationship between educational attainment and job satisfaction [27,35]. Kim et al. (2014) [27] used the National Longitudinal Study of the High School Class of 1972 (NLS), the sophomore cohort of the High School and Beyond Survey of 1980 (HSB), and the National Education Longitudinal Studies of 1988 (NELS) to explore the relationship between institutional selectivity and occupational outcomes over time. They found that there is no significant association between college selectivity and job satisfaction. In addition, a recent study from the meta-analysis and empirical study based on the data from the Household, Income, and Labor Dynamics in Australia survey found that neither their meta-analysis nor the empirical study showed that highly educated individuals tended to have higher job satisfaction. Although better-educated individuals have greater income, job autonomy, and job variety, they also receive more demands from their jobs, such as longer work hours, more pressure from tasks, higher job intensity, and higher time urgency, which negatively associated with job satisfaction, indicating a trade-off between educational credentials and job satisfaction [36]. From the discussion above, we can see that educational qualifications might be directly related to the extrinsic outcomes of employment, such as earnings, and intrinsic outcomes, such as job quality, but it might vary by different country regimes and overtime.

2.6. Research Hypothesis

It is important to consider the intersection between gender and educational attainment, and how educational attainment affects the gender gap of employment and job quality. No research in the past has investigated the relationships between educational attainment and gender gaps in job quality across different nations or welfare regimes. Previous research focused on whether education can raise the earnings of individuals rather than the intersection of education level and gender to explore job quality. Moreover, differences in welfare regimes could further highlight the possibility of different patterns of job quality in terms of educational attainment and gender. We hypothesize that women will experience different job experience and quality (possibly lower) in terms of work autonomy, work intensity, and job satisfaction compared to men of the same education. Secondly, based on Esping-Anderson’s (1990) [3] welfare capitalism theory, we hypothesize that job quality differences among genders will be more prominent in Germany and the UK compared to Sweden. We conclude by discussing similarities and differences in patterns among these three nations.

3. Method

The primary purpose of this research is to understand the relationship between gender and job quality in three European countries—Germany, Sweden, and the UK. Factors including education, sector, blue/white collar, and employment status were analyzed. To answer this question, we collected data from a large sample through a representative questionnaire survey. The data and analysis are based on the 6th European Working Conditions Survey for 2015 [37,38]. The European Working Conditions Survey (2015) was conducted by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Condition’s survey partners, Ipsos NV. The respondents were all aged fifteen and above, and they were all in employment at the time of the interview. Individuals who were paid to work were considered employed. The sampling procedure was multi-stage, stratified, and random.

Since the focus of this research is on comparing Germany, Sweden, and the UK, only the data from these three countries were selected, which is representative of the population in each of the target countries. The sampling units were drawn according to each country’s degree of urbanization. It used the sampling strategy of selection probability, which makes it possible to deduce the data of the whole population. Although the European Working Conditions Survey covers various topics and includes various variables, only its subset data were chosen for this study. While the focus is on education and gender, other variables, such as sector and employment, were also taken into consideration. Germany had 2093 data points, while Sweden had 1002 data points, and the UK had 1623 data points. The total number of data points was 4718.

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Dependent Variables

Work Autonomy. Work autonomy ratings were obtained using three items from the European Working Conditions Survey (2015) to measure how employees have control and timing on their jobs. The three items include: (1) Are you able to choose or change your order of tasks? (2) Are you able to choose or change your methods of work? (3) Are you able to choose or change your speed or rate of work? Following the scale created by Holman and Rafferty (2018) [39], the mean of these items was calculated and standardized to a score of 0–100. The Cronbach alpha was 0.69.

Work Intensity. The work intensity scale is a 10-item scale capturing intensive labor effort from physical, cognitive, and emotional aspects. The ten items include: (1) working at very high speed; (2) working to tight deadlines; (3) the work done by colleagues; (4) direct demands from people, such as customers, passengers, pupils, and patients; (5) numerical production targets or performance targets; (6) automatic speed of a machine or movement of a product; (7) the direct control of your boss; (8) you have enough time to get the job done; (9) your job requires that you hide your feelings; and (10) handling angry clients, customers, patients, etc. Following the scale created by Smith et al. (2013) [5], the mean of these items was calculated and standardized to a score of 0–100. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.63.

Job Satisfaction. Four items were suggested by Feldman et al. (2002) and Wu et al. (2015) [8,9] to measure subjective job satisfaction. These involve satisfaction with payment, career advancement, and attitudes towards the organization and the work itself. The four items are: (1) On the whole, are you satisfied or not satisfied; (2) Considering all my efforts and achievements in my job, I feel I get paid appropriately; (3) My job offers good prospects for career advancement; and (4) I receive the recognition I deserve for my work. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74.

3.1.2. Independent Variables

Gender. Female was coded as 1, and male was coded as 0 for the analysis.

Sector. Originally, there were multiple categories, including private sector, public sector, joint private public organization or company, not-for-profit sector, NGO, and other in this variable. These were then simplified into two categories: private and public. The joint private public organization or company category was placed into the public sector category and coded as non-for-profit sector, while the NGO category was placed into the private sector category.

Educational Level. Educational level is distinguished among three types according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED): low educational level (ISCED 1–3), medium educational level (ISCED 4–5), and high educational level (ISCED 6–9).

3.1.3. Control Variables

Blue/White Collars. We used the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) to classify the types of occupations into three categories: high-skilled white collar (ISCO category 1–3, including managers, professionals, technicians, and associate professionals), low-skilled white collar (ISCO category 4 and 5, including clerical support workers, service, and sales workers), and low-skilled blue collar (ISCO category 6–9, e.g., skilled agricultural and fishery workers, craft and related trade workers, elementary occupations).

Full-time/Part-time. Only one item, “Do you work part time or full time?”, was used to capture whether the person worked full time or part time.

3.2. Analysis Procedures

We first examine the descriptive statistics of the employment-related characteristics and gender distribution, which are key independent variables of our study. Next, we demonstrate the distributions, Cronbach’s alphas, and intercorrelations among the dependent variables, which include the three dimensions of our job quality measures: work intensity, work autonomy and job satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha is especially useful to show the reliability of our job quality measures given that they are constructed by a set of questions from Likert scale surveys. Intercorrelations demonstrate whether these job quality measures themselves are positively or negatively related. In addition, we also show the intercorrelations of age with these job quality measures since it helps shed light on how job quality changes over the workers’ age in our study.

Following that, we specify multivariate regression analysis predicting work intensity, work autonomy, and job satisfaction with two-way and three-way interactions of gender, higher education attainment, and national regimes. Specifically:

For each worker, represents the three dimensions of their job quality, work intensity, and work autonomy and job satisfaction; are vectors of coefficients of sectors and countries, which are categorical measures. Specifically, contains two coefficients of the additional associations of low-skilled white collar and high-skilled white collar with job quality relative to blue collar, which is the reference group. contains two coefficients of the additional associations of Germany and the UK with job quality relative to Sweden, which is the reference group. is the intercept and is the idiosyncratic error term. Importantly, given that we included both two-way and three-way interactions in the model, we account for all coefficients related to our key independent variables in interpretation and conducted specific statistical tests. For instance, the conditional association of gender is calculated based on in the model.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the independent variables, and Table 2 demonstrates the scales descriptive statistics of the dependent variables, including means, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha and intercorrelations among the scales. As is shown, the correlation between work autonomy and work intensity is significant and negative (−0.15, p < 0.01); job satisfaction and work intensity is significant and negative (−0.23, p < 0.01); age and work intensity is significant and negative (−0.10, p < 0.01); and age and job satisfaction is significant and negative (−0.10, p < 0.01). However, the correlation between job satisfaction and work autonomy is significant and positive (0.25, p < 0.01), as is the correlation between age and work autonomy (0.08, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the independent variables.

Table 2.

Scale Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Construct.

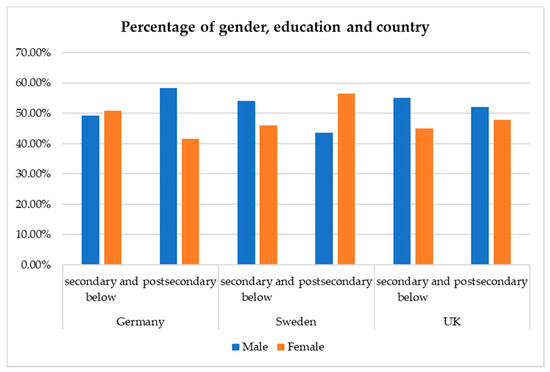

Statistics pertaining to gender, education, and country are shown in Figure 1. The percentage of Swedish women who received postsecondary education is higher than the percentage of women with the same educational level in Germany and the UK. As the first outcome of job autonomy, we focused on the gender differences in work autonomy by educational groups across the contexts of Sweden, Germany, and the UK. To achieve this goal, we specified saturated models, including both two-way and three-way interaction terms of the relevant variables.

Figure 1.

Percentage of gender, education, and country.

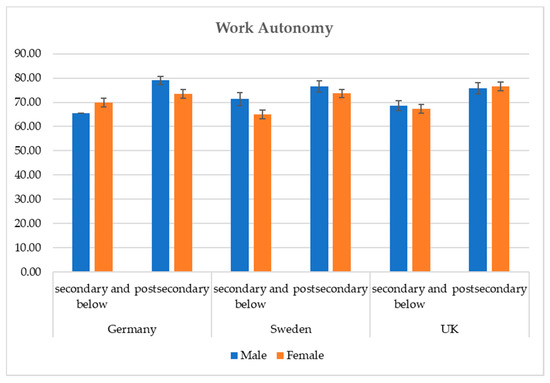

Work autonomy is the first important measure of job quality on which our paper focuses. Figure 2 shows the margins of gender and educational level in Germany, Sweden, and the UK. Table 3 shows that German men who received primary and secondary education have less work autonomy compared to Swedish men who received similar education (−5.78, p < 0.05). In contrast to men, German women who received primary and secondary education show a slightly higher level of work autonomy (1.41) compared to Swedish women with similar education although the difference is not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

The predicted conditional means of work autonomy score by gender, educational level, and country.

Table 3.

Regression results for the pooled sample for gender, education, and country.

The gender pattern of work autonomy in Germany differs from that of Sweden, especially for those of the lower educational group. German women who have a primary and secondary education tend to have a higher level of work autonomy compared to men who belong to the same education group (4.31, not statistically significant at 0.05 level). Swedish women who have a primary and secondary education tend to have a lower work autonomy compared to men who belong to the same education group (−6.32, not statistically significant at 0.05 level). Therefore, the gender gap of work autonomy is reversed between Swedish and German people who only received primary and secondary education, and the country difference of the gender gap is statistically significant from zero (10.63, p < 0.05).

In contrast to Sweden, higher education does not grant the same benefit for women in terms of work autonomy as in Germany. Compared to those who only receive secondary education and lower, German women who received postsecondary education have a slightly higher level of work autonomy (3.57, not statistically significant at 0.05 level). Swedish women who received postsecondary education have a slightly higher level of work autonomy compared to Swedish women with primary and secondary education who do not (8.62, not statistically significant at 0.05 level). Therefore, postsecondary education makes a different impact on gender gaps in work autonomy among women in Germany and Sweden. While postsecondary education lowers the gender gap in work autonomy in Sweden, postsecondary education can increase the gender gap in work autonomy in Germany. Such differences in the “effect” of higher education are remarkable (−13.38, p < 0.05).

German men who receive postsecondary education tend to have a higher level of work autonomy compared to men who received primary and secondary education (13.51, statistically significant at 0.05 level). Swedish men who receive postsecondary education tend to have a higher level of work autonomy compared to men who received primary and secondary education (5.17, not statistically significant at 0.05 level). The gap in work autonomy for men with different educational levels is higher in Germany than in Sweden (8.34, p < 0.05).

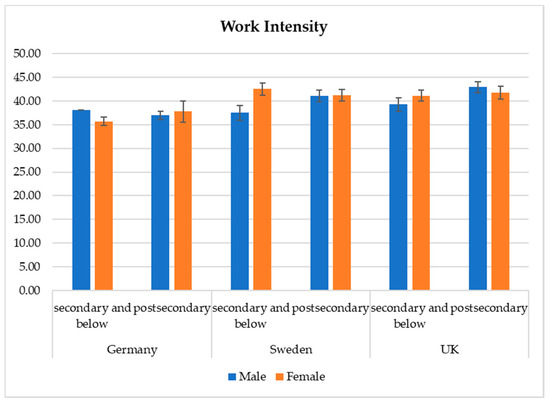

Work intensity is another important measure of job quality. Figure 3 shows the margins of gender and educational level in Germany, Sweden, and the UK. Table 3 shows that higher scores of work intensity indicate a less favorable job quality. Similar to the models predicting work autonomy, we included both two-way and three-way interactions of gender, country, and education levels to predict work intensity to reveal the relationship between gender norms and education institutions across welfare-state regimes. As is shown by Model 2 of Table 3, gender inequality in differences of job intensity is large and statistically significant in Germany and Sweden but not in the UK.

Figure 3.

The predicted conditional means of work autonomy score by gender, educational level, and country.

Specifically, Swedish women received primary and secondary education are shown to have a higher work intensity compared to Swedish men who are in the same education group (5.02, p < 0.05). Highly educated Swedish men who received postsecondary education have higher work intensity compared to those men who do not (3.54, p < 0.05). In contrast to men, Swedish women who are highly educated show a slightly lower work intensity compared to the Swedish women who only have received primary or secondary education (−1.3, not statistically significant) although it is not statistically significant. Generally speaking, postsecondary education can significantly reduce the gender gap of work intensity in Sweden (−4.83, p < 0.05).

The gender pattern of work intensity in Germany differs from that of Sweden, especially for those of the lower educational group. Remarkably, German women who have a primary and secondary education tend to have a lower work intensity compared to men who belong to the same education group (−2.44, not statistically significant at 0.05 level) rather than higher, as in Sweden (5.02, not statistically significant). Therefore, the gender gap of work intensity is reversed between Swedish and German people who only received primary and secondary education, and the country difference is statistically significant from zero (−7.46, p < 0.01). Compared to Sweden, higher education does not grant the same benefit for women in Germany in terms of work intensity. Indeed, German women who received postsecondary education have a slightly higher work intensity compared to German women who do not (2.02, not statistically significant at 0.05 level). Therefore, postsecondary education makes a different impact on gender gaps in work intensity among people in Germany and Sweden. While postsecondary education lowers the gender gap in work intensity in Sweden, postsecondary education can increase the gender gap in work intensity in Germany. Such differences in the “effect” of higher education are again remarkable (8.09, p < 0.05).

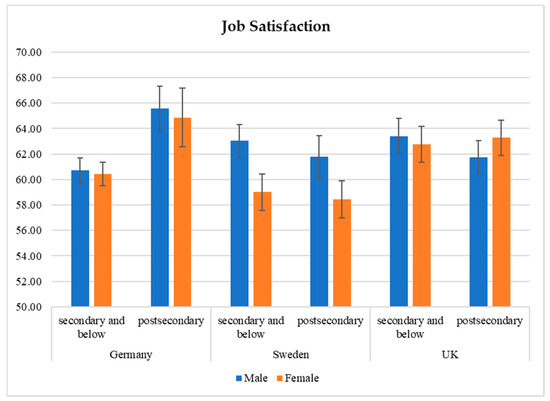

Job satisfaction is our last measure of job quality. Figure 4 shows the margins of gender and educational level in Germany, Sweden, and the UK. Compared to autonomy or intensity, which reflect specific aspects of a job, satisfaction captures people’s subjective and overall evaluation of their workplace experience. As is shown in Model 3 of Table 3, Swedish women who have primary and secondary education show a lower job satisfaction in comparison to Swedish men of the same education group (−4.03, p < 0.05). This corresponds to the fact that they have a higher work intensity, as is shown in Model 2 of the same table (5.02, p < 0.05). In general, Swedish males and females who have postsecondary education show a similar or lower job satisfaction compared to those in a lower education group. In addition, postsecondary education does not significantly decrease the gender difference in job satisfaction in Sweden (0.7, not statistically significant) as it does to work intensity.

Figure 4.

The predicted conditional means of job satisfaction score by gender, educational level, and country.

For the group with secondary or primary education, gender gaps in work satisfaction do not differ significantly across Sweden, the UK, and Germany. In Germany, postsecondary education increases job satisfaction for males (4.84, not statistically significant) and, to a similar degree, for females (4.44, not statistically significant), which is different from the scenario in Sweden. Besides, postsecondary education increases job satisfaction more significantly among German males (by 6.11, p < 0.05) than among Swedish males.

4.2. Conclusions and Discussion

This research investigated the relationship between gender and educational attainment on job quality by using data from the European Working Condition Survey 2015. In answering the first research question, “To what extent does gender affect job quality, including work intensity, work autonomy, and job satisfaction across nation regimes?”, we provide evidence of gender inequality given the same educational level across countries, confirming past findings. In addressing the second research question, “How does higher education affects the gender gap of job quality?”, we render new evidence that post-secondary education affects the gender gap of job quality in different ways across regimes, challenging the conventional belief that education closes gender gaps of labor-market outcomes universally. Correspondingly, our empirical findings are summarized in these two aspects. First, there exists significant gender inequality in work autonomy, intensity, and satisfaction within the same educational groups across Germany and Sweden. For instance, among those with postsecondary education, German females have a lower work autonomy than German males, and among those with secondary education, Swedish females have a lower autonomy and higher work intensity than Swedish males. Therefore, even when women have attained the same level of education as men, women still face unequal conditions in job quality compared to men, which is alarming. Second, postsecondary education makes a different impact on gender gaps in work autonomy and intensity among people in Germany and Sweden. While postsecondary education lowers the gender gap of work autonomy and intensity in Sweden, postsecondary education can increase the gender gap of work autonomy and intensity in Germany. We attempt to explain this complexity based on the institutions of different gender norms and gender occupation segregation in Germany and Sweden. Overall, although educational capital helps individuals to secure more privileged positions in the job market [33], privileged jobs might not always equal high job quality. Our study implies that it is necessary to bring in the dimension of country regimes to the discussion of gender inequality in job quality and how higher education institutions play a role in mitigating the gender gaps.

Sweden features a “weak male breadwinner” model that represents the social-democratic state. The state provides childcare through direct public provision. Policies encourage all citizens to participate in the labor market regardless of gender differences [1]. Our study suggests that receiving postsecondary education gives women the possibility of having good jobs. Swedish women who have received primary and secondary education are shown to have a significantly higher work intensity compared to Swedish men of the same education, but such gender difference in work intensity diminishes when looking at Swedish men and women who receive a postsecondary education. In general, higher education plays an important role in lifting Swedish women’s job quality. In Sweden, the main challenge of gender equity seems to lie with the welfare and job quality of low-educated women, who receive only primary and secondary education.

In Germany, women who have a primary and secondary education tend to have a lower work intensity compared to men who belong to the same education group, which is different from the patterns in Sweden. One possibility is that German women tend to work in jobs that do not require intensive labor. A lower-intensity work arrangement allows them to spend more time taking care of their families, which aligns with the typical gender norm under Germany’s strong male breadwinner model. Such difference in gender norms between Sweden and Germany is also evident in the gender-education distribution in the respective countries, for which we presented the fact that a much lower proportion of German women receive postsecondary education in Germany than in Sweden.

The most remarkable finding of our study is that postsecondary education institutions produce opposite effects to the gender gaps of job quality (including work intensity and autonomy) in different contexts. While postsecondary education lowers the gender gap in work intensity and autonomy in Sweden, postsecondary education can increase the gender gap in work intensity and autonomy in Germany. This seemingly counterintuitive finding may have its roots in the different institutional contexts of Germany and Sweden. In Germany, the occupational structure is highly segmented gender-wise, especially regarding vocational specializations. Lower-skilled women are concentrated in service sectors. Not only do these women usually enter the job market through a different vocational education track (i.e., school-based vocational training) than males (dual system vocational training), they also experience gender segmentation in work concerning work intensity, occupational hierarchies, and rewards [40]. In comparison, the occupational structure in Sweden features less gendered segregation. Furthermore, the higher gender equality in Sweden may suggest that the norms for females to participate in the labor market are more “universal”, and low-skilled women may therefore engage in more intensive blue-collar work since they feel more compelled to work. By contrast, lower-educated German women who are in the labor market can be a more selective group compared to Swedish women since the former may perceive it more comfortable to be housewives under the strong male breadwinner norms of Germany. Given the different gender norms of education and work, German women who choose postsecondary education can also be a more selective group compared to Swedish women, especially in terms of their willingness to engage in more intensive work, which features white-collar work environments in Germany. Therefore, higher education may show the interesting effect of lowering the gender gap of work intensity in Sweden while raising the gender gap of work intensity in Germany. These findings challenge the conventional belief in the universal “equalizing effect” of higher education on labor market outcomes. They also add nuance to the picture by stressing the importance of the specific gender norms of work, education, and different national regimes.

There are several limitations to this study. First, given our relatively small sample size, some interactive effects estimates are not statistically significant from zero, so we cannot conclude all the subgroups of gender, education, and county of interest. Related to the first limitation, our estimates of the UK are not significant, so we cannot construct a more systematic theory of gender, work, and welfare-state institutions. For this reason, we only discuss results based on Sweden and Germany. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the measurement of the outcome variables may be inherently gendered. For instance, women and men may have different motivations to get involved in high-intensity jobs and different perceptions due to gender norms, which may unavoidably affect their job satisfaction. If males have fewer concerns over balancing work with their family duties, especially in countries like Germany, they may engage in high-intensity jobs without sacrificing their job satisfaction. However, the same reasoning may not be as convincing for women as men. While our measures of job autonomy, intensity, and satisfaction are all self-reported and normative in nature, they are important measures that reflect the subjective wellbeing attached to different types of work in different contexts. Future studies may engage more objective measures of the job market experience, such as working hours, required skills, promotion and demotion experiences, and the consequences of interruptions to employment, to better our understanding of gender inequality in job experiences across contexts.

As an inherent part of the goals of sustainable development, the United Nations has encouraged national governments to formulate policies that encourage gender equality in the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development AGENDA 2 in 1992 [2]. Our research underscores the importance of considering the intersections of gender norms, work environment, education system, and national institutions to address issues of gender inequality. Measures promoting gender inequality in chapter 24 of United Nations Conference on Environment & Development AGENDA 21 (1992) are inseparable from measures related to education equity in Chapter 36 of the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development AGENDA 21 and workers’ rights in Chapter 29 of the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development AGENDA 21. For countries with a more stratified educational system, such as Germany, it may be important to address issues of gender segregation in the vocational education system, change the values and norms which discourage women from having higher educational aspirations and men from taking a more equal role in the households, and to promote work-life balance policies in both blue-collar sectors and white-collar sectors. For countries with a more “equalized” education system and more “universal” norms of work across gender, such as Sweden, more attention should be paid to promote gender equality in the workplace and to close the gender gaps of job quality. It may be advisable to increase the awareness of gender inequality in job quality across workplaces, ensure equal access to adequate training and opportunities of promotion, and provide or improve employee-based decision-making mechanisms regarding work environment and workplace opportunities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-J.W., J.H., and X.X.; methodology, Y.-J.W., J.H., and X.X.; data analysis, Y.-J.W., J.H., and X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-J.W., J.H., and X.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.-J.W., J.H., and X.X.; visualization, Y.-J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable (the study did not require Institutional Review Board’s Statement nor approval, because it uses only publicly available data).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found at https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/about-eurofound-surveys/data-availability.

Acknowledgments

We would also like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rubery, J.; Grimshaw, D. The Organization of Employment: An International Perspective; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Environment; Development AGENDA 21 (1992). Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, Y. Working-time flexibility and autonomy: A European perspective on time adequacy. Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2014, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Piasna, A.; Burchell, B.; Rubery, J.; Rafferty, A.; Rose, J.; Carter, L. Women, Men and Working Conditions in Europe; European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions: Dublin, Ireland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Green, F. Decent Work and the Quality of Work and Employment. In Human Resources and Population Economics; Zimmermann, K.F., Ed.; Online; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Verhofstadt, E.; De Witte, H.; Omey, E. Higher educated workers: Better jobs but less satisfied? Int. J. Manpow. 2007, 28, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.C.; Leana, C.R.; Bolino, M.C. Underemployment and relative deprivation among re-employed executives. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2002, 75, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.H.; Luksyte, A.; Parker, S.K. Overqualification and subjective well-being at work: The moderating role of job autonomy and culture. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 917–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drafke, M.W.; Kossen, S. The Human Side of Organizations, 8th ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gambles, R.; Lewis, S.; Rapoport, R. The Myth of Work–Life Balance: The Challenge of Our Time for Men, Women, and Societies; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlau, P. Gender inequality and job quality in Europe. Manag. Rev. 2011, 22, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brynin, M. Overqualification in employment. Work. Employ. Soc. 2002, 16, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilmaghani, M.; Tabvuma, V. The gender gap in work–life balance satisfaction across occupations. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 34, 398–428.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauret, L.; Williams, D.R. Cross-national analysis of gender differences in job satisfaction. Ind. Relat. A J. Econ. Soc. 2017, 56, 203–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evertsson, M.; England, P.; Mooi-Reci, I.; Hermsen, J.; de Bruijn, J.; Cotter, D. Is gender inequality greater at lower or higher educational levels? Common patterns in the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States. Soc. Politics. 2009, 16, 210–241. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, C.; Kerr, S.P.; Olivetti, C.; Barth, E. The expanding gender earnings gap: Evidence from the LEHD-2000 Census. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bihagen, E.; Nermo, M.; Stern, C. The gender gap in the business elite: Stability and change in characteristics of Swedish top wage earners in large private companies, 1993–2007. Acta Sociol. 2014, 57, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokemeier, J.L.; Lacy, W.B. Job values, rewards, and work conditions as factors in job satisfaction among men and women. Sociol. Q. 1987, 28, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.; Torregrosa, R.J. The gender-job satisfaction paradox through time and countries. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2021, 28, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, K.U. The Paradox of Global Social Change and National Path Dependencies. In Inclusion and Exclusion in European Societies; Woodward, A., Kohli, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hofäcker, D.; König, S. Flexibility and work-life conflict in times of crisis: A gender perspective. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2012, 33, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J. Higher education as a filter. J. Public Econ. 1973, 2, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, D.B. Credentials, Signals, and Screens: Explaining the Relationship between Schooling and Job Assignment. Rev. Educ. Res. 2003, 73, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allmendinger, J. Educational systems and labor market outcomes. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 1989, 5, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Neumann, M.; Dumont, H. Recent developments in school tracking practices in Germany: An overview and outlook on future trends. Orb. Sch. 2017, 10, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Jaquette, O.; Bastedo, M.N. Institutional stratification and the postcollege labor market: Comparing job satisfaction and prestige across generations. J. High. Educ. 2014, 85, 761–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kurz, K. Precarious Employment, Education and Gender: A Comparison of Germany and the United Kingdom. Working Paper No. 39.; Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung: Mannheim, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, W.; Shavit, Y. The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A Comparative Study of Qualifications and Occupations in Thirteen Countries. In From School to Work. A Comparative Study of Educational Qualifications and Occupational Destinations; Shavit, Y., Müller, W., Eds.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Ministry of Education and Research. OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resources Use in Schools-Country Background Report; OECD: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/CBR_OECD_SRR_SE-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Bol, T.; Van de Werfhorst, H.G. Signals and closure by degrees: The education effect across 15 European countries. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2011, 29, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoles, A.; Meschi, E. The Determinants of Non-Cognitive and Cognitive Schooling Outcomes. In Report to the Department of Children, Schools and Families; Report No. 004; Centre for the Economics of Education (NJ1): London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; National Bureau of Economic Research: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Piróg, D. The impact of degree programme educational capital on the transition of graduates to the labour market. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 41, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudde, L.; Bernell, K. Educational Attainment and Nonwage Labor Market Returns in the United States. AERA Open 2019, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, B.C.; Nikolaev, B.N.; Shepherd, D.A. Does educational attainment promote job satisfaction? The bittersweet trade-offs between job resources, demands, and stress. J. Appl. Psychol. 2021. Advance online publication. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2021-37667-001 (accessed on 1 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Sixth European Working Conditions Survey–Overview Report (2017 Update); Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. European Working Conditions Survey, 2015 [Data Collection], 4th ed.; UK Data Service; Eurofound: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, D.; Rafferty, A. The Convergence and Divergence of Job Discretion Between Occupations and Institutional Regimes in Europe from 1995 to 2010. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 619–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasler, S.R. The German system of vocational education and training: Challenges of gender, academisation and the integration of low-achieving youth. Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2020, 26, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).