Learning through Play: A Serious Game as a Tool to Support Circular Economy Education and Business Model Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

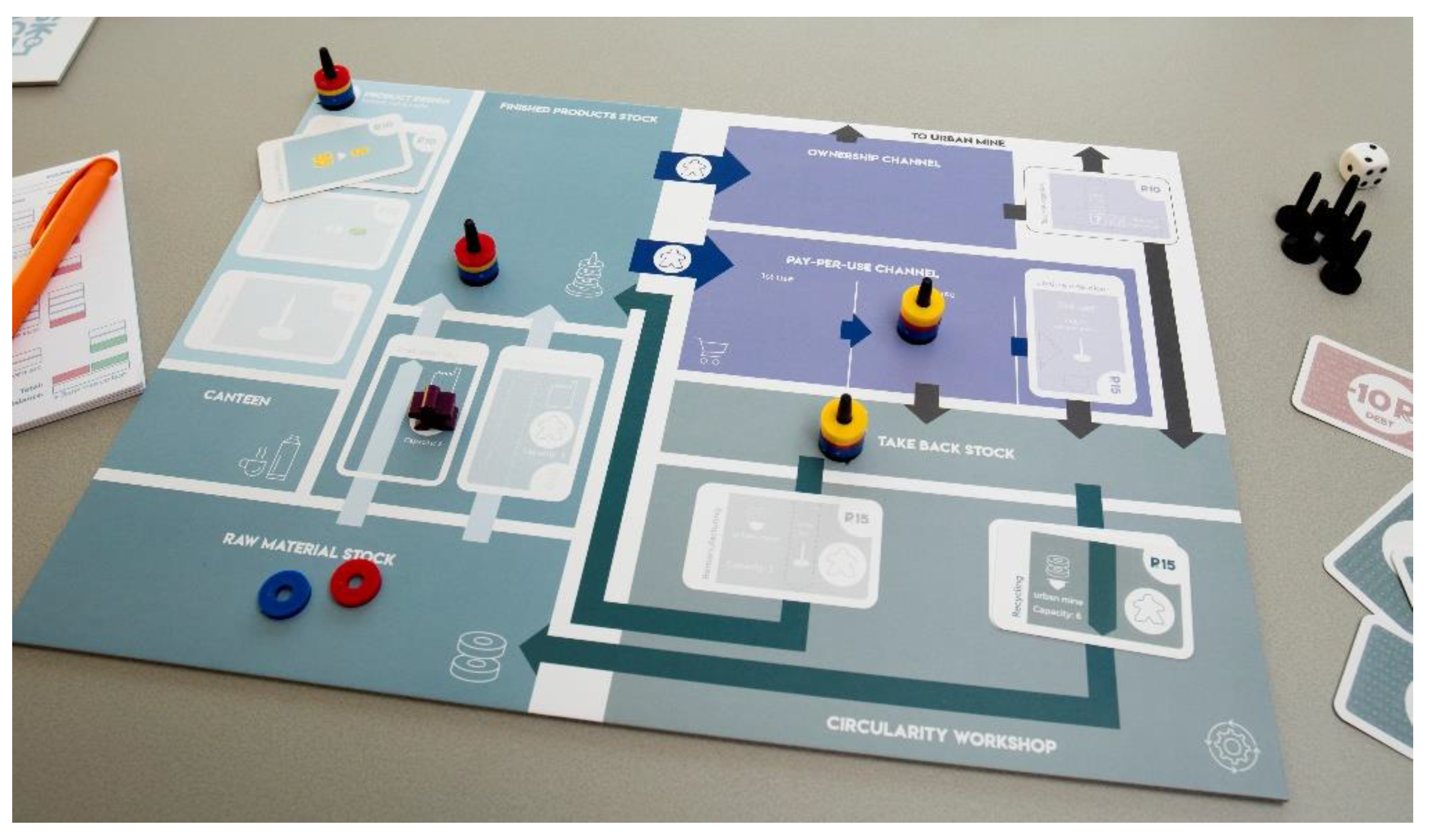

2. Materials and Methods: The Serious Game Risk&RACE

2.1. Game-Based Learning and Serious Games

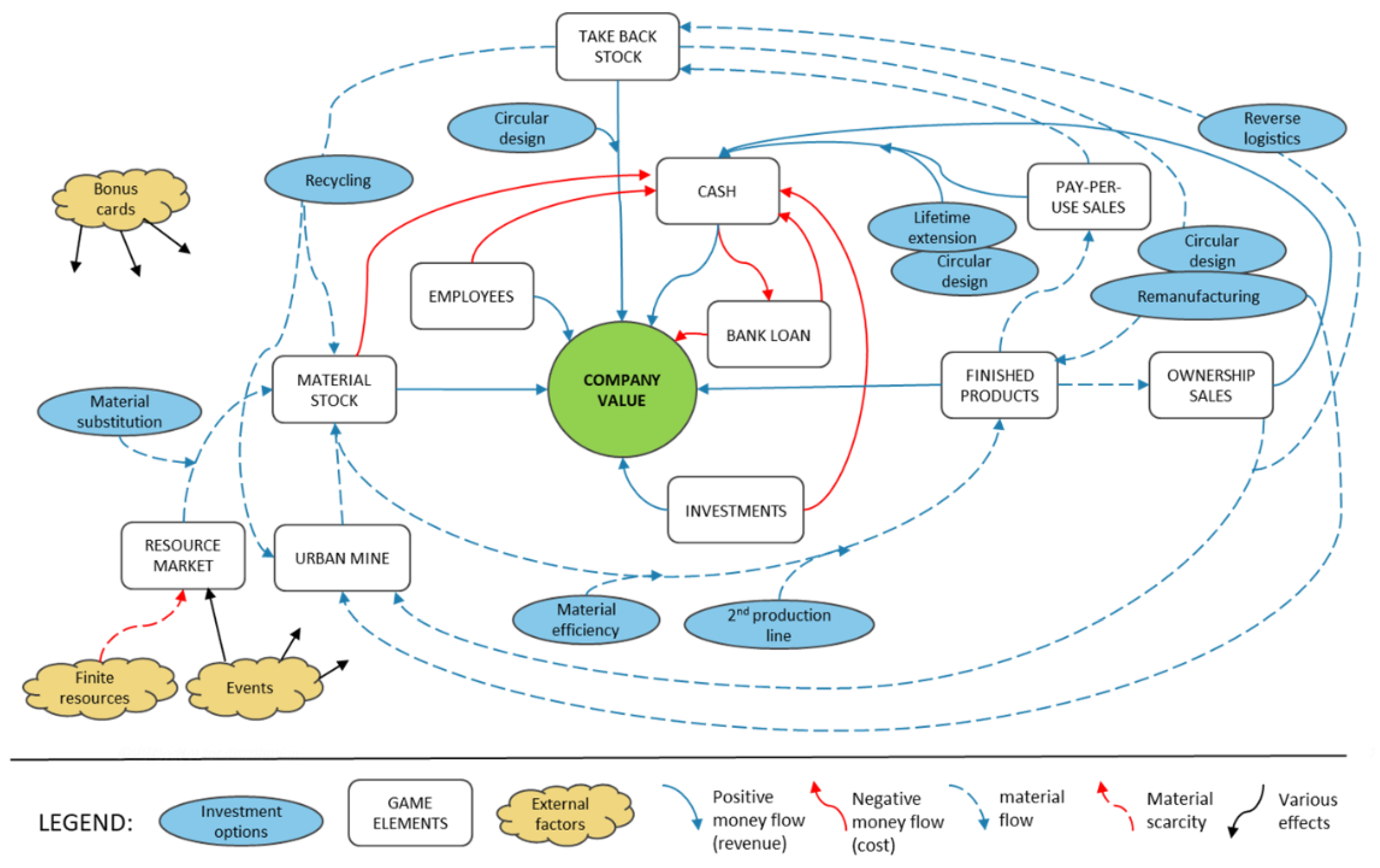

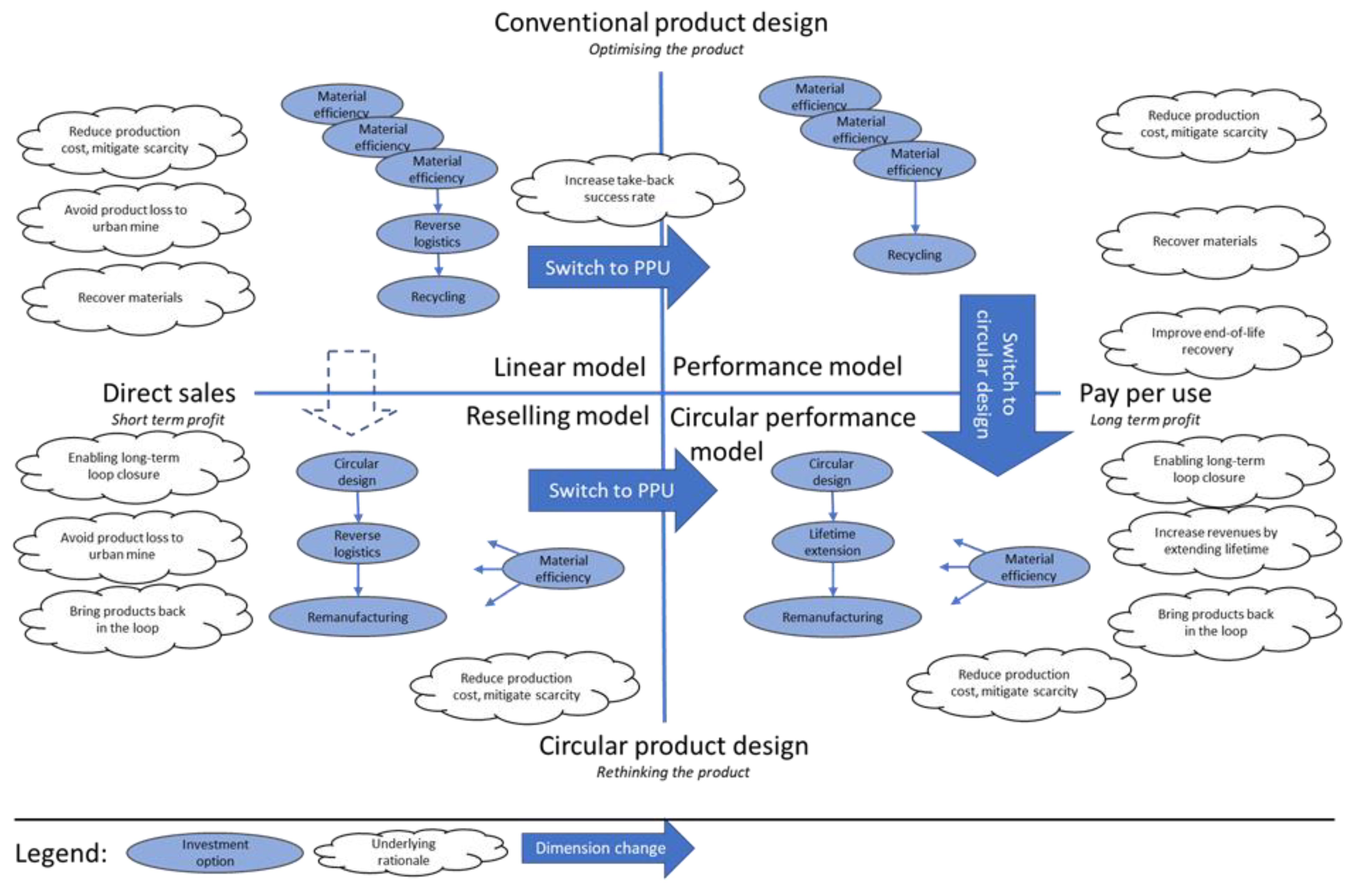

2.2. Risk&RACE Learning Goals and Game Mechanics

2.3. Workshop Setup

2.4. Data Gathering and Analysis

2.4.1. Observations

2.4.2. Post-Game Surveys

3. Results

3.1. Observed Player Strategies

3.2. Reported Key Insights

3.2.1. External Pressures—Why Is Circular Economy Important?

3.2.2. Circular Strategies—What Needs to Be Done to Make Products Circular?

3.2.3. Business Models and Entrepreneurship—How Can Circular Business Models Contribute to a Successful Business?

3.3. Risk&RACE as a Learning Tool on Circular Economy

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognitive Learning Outcomes of the Simulation Game

4.2. Affective Outcomes Induced by the Simulation Game

4.3. The Simulation Game as a Learning Tool

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Risk&RACE Gameplay

Appendix A.1. Aim

Appendix A.2. Setup

Appendix A.3. Game Scenario

Appendix A.4. Round Sequence

| Investment | Advantage in the Game | Trade-Offs and Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Material efficiency | Reduces the amount of materials that are needed to make a product | Reduces efficiency of recycling |

| Material substitution | Enables players to exchange a material type for a cheaper, renewable or less scarce material | Substituting materials can also be limited |

| Reverse logistics | Allows players to take back products sold in ownership before they become waste | It is uncertain how many used products are effectively returned. |

| Recycling | Makes it possible to recover materials from end-of-life products, regardless of their design | Considerable process inefficiencies cause material loss, and recycled materials can only be used in the next round, causing delay |

| Product life extension | Supports the longer use of products, yielding additional revenues in pay-per-use | Requires the investment Circular design as a prerequisite and lengthens the time before a product can be recycled or remanufactured |

| Remanufacturing | Supports the disassembly and remanufacturing of take-back products, avoiding primary production costs and shortening production time | Requires the investment Circular design as a prerequisite; requires skilled labour |

| Circular design | Enables Product life extension and Remanufacturing | Does not improve circularity or increase revenues by itself, but needs to be complemented by end-of-life strategies such as product life extension or remanufacturing. |

| 2nd production line | Increases production capacity | Applicability is highly vulnerable to supply disruptions and resource constraints |

Appendix A.5. End of the Game

Appendix B. Survey Questions

- After having played Risk&RACE, what are the main lessons or eye-openers you experienced?

- Now that you have played, for each term/concept presented below, please select to what extent playing the game has affected your understanding of the term/concept.

| After Playing the Game, I Feel My Understanding of the Term/Concept Has: | ||

| Improved | Not Changed | |

| Fixed cost | ||

| Variable cost | ||

| Free cash flow | ||

| Payback time | ||

| Return on investment | ||

| Product service systems | ||

| Circular Economy | ||

| After Playing the Game, I Feel My Understanding of The Term/Concept Has: | ||

| Improved | Not Changed | |

| Circular design | ||

| Resource efficiency | ||

| Recycling | ||

| Remanufacturing | ||

| Product life extension | ||

| Reverse logistics | ||

| Substitution | ||

- 3.

- Please indicate which aspects you liked about Risk&RACE?

- 4.

- Please indicate which aspects you didn’t like or would like to see improved?

- 5.

- What is your overall impression of Risk&RACE as a learning tool on circular economy strategies and business models?

References

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Circle Economy. Jobs and Skills in the Circular Economy. 2020. Available online: https://assets.website-files.com/5d26d80e8836af2d12ed1269/5e6897dafe8092a5a678a16e_202003010%20-%20J%26S%20in%20the%20circular%20economy%20report%20-%20297x210.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Growth within: A Circular Economy Vision for a Competitive Europe. Ellen MacArthur Foundation Publishing. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/EllenMacArthurFoundation_Growth-Within_July15.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe COM/2020/98 Final 2020; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Drabik, E.; Rinaldi, D.; Tuokko, K. Role of Business in the Circular Economy: Markets, Processes and Enabling Policies; Report of a CEPS Task Force; Centre for European Policy Studies: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador, R.; Barros, M.V.; da Luz, L.M.; Piekarski, C.M.; de Francisco, A.C. Circular business models: Current aspects that influence implementation and unaddressed subjects. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 250, 119555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Europe. Circulary—Circular Economy Industry Platform. Available online: http://www.circulary.eu/sectors (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Circulator Home—Circulator. Available online: http://circulator.eu/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Economy Case Studies. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/case-studies (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 26, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking circular business: A framework of barriers and drivers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 212, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stahel, W.R. Policy for material efficiency—Sustainable taxation as a departure from the throwaway society. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2013, 371, 20110567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Ritala, P.; Huotari, P. The Circular Economy: Exploring the Introduction of the Concept Among S&P 500 Firms. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WBCSD. 8 Business Cases for the Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/Circular-Economy/Factor-10/Resources/8-Business-Cases-to-the-Circular-Economy (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Bocken, N.; Short, S. Towards a sufficiency-driven business model: Experiences and opportunities. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2015, 18, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lewandowski, M. Designing the business models for circular economy—Towards the conceptual framework. Sustainability 2016, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldmann, E.; Huulgaard, R.D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 243, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Business model innovation for circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roobeek, A.; de Ritter, M. Rethinking Business Education for Relevance in Business and Society in Times of Disruptive Change. In Proceedings of the AoM, Anaheim, CA, USA, 5–9 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.; Schuit, C.; Kraaijenhagen, C. Experimenting with a circular business model: Lessons from eight cases. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 28, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno, M.; De Los Rios, C.; Rowe, Z.; Charnley, F. A Conceptual Framework for Circular Design. Sustainability 2016, 8, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chappin, E.J.; Bijvoet, X.; Oei, A. Teaching sustainability to a broad audience through an entertainment game—The effect of Catan: Oil Springs. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, K.A.; Berlin, C.; Ekberg, J.; Barletta, I.; Hammersberg, P. ‘All they do is win’: Lessons learned from use of a serious game for Circular Economy education. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coursera Circular Economy—Sustainable Materials Management. Available online: https://www.coursera.org/learn/circular-economy (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- EdX Circular Economy: An Introduction. Available online: https://www.edx.org/course/circular-economy-an-introduction (accessed on 2 April 2021).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation a Global Snapshot of Circular Economy Learning Offerings in Higher Education. Available online: https://indd.adobe.com/view/0a75325c-0a0f-4c57-8868-4bf550bc4e66 (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Bocken, N.; Strupeit, L.; Whalen, K.; Nußholz, J. A Review and Evaluation of Circular Business Model Innovation Tools. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, M.; Clark, K.R. Game-based Learning and 21st century skills: A review of recent research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Mazzuto, G.; Paciarotti, C. “Cook &Teach”: Learning by playing. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, P.; Van Nimwegen, C.; Van Oostendorp, H.; Van Der Spek, E.D. A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, L.; Ulrich, M.; Seele, P. Education for sustainable development through business simulation games: An exploratory study of sustainability gamification and its effects on students’ learning outcomes. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 207, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, K. Risk & Race: Creation of a finance-focused circular economy serious game. In PLATE: Product Lifetimes and The Environment—Conference Proceedings of PLATE 2017, Delft, The Netherlands, 8–10 November 2017; Delft University of Technology and IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 9, pp. 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.B.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Killingsworth, S.S. Digital Games, Design, and Learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Connolly, T.M.; Boyle, E.A.; MacArthur, E.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 661–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.; Hainey, T.; Baxter, G. A Systematic Literature Review to Identify Empirical Evidence on the Use of Computer Games in Business Education and Training. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Games Based Learning, Scotland, UK, 6–7 October 2016; Volume 1, pp. 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Vlachopoulos, D.; Makri, A. The effect of games and simulations on higher education: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjællingsdal, K.S.; Klöckner, C.A. Green across the Board: Board Games as Tools for Dialogue and Simplified Environmental Communication. Simul. Gaming 2020, 51, 632–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, C.C. Serious Games; Viking Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, R.L.; Suárez, A.M. Gaming to succeed in college: Protocol for a scoping review of quantitative studies on the design and use of serious games for enhancing teaching and learning in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2020, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhonggen, Y. A Meta-Analysis of Use of Serious Games in Education over a Decade. Int. J. Comput. Games Technol. 2019, 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de la Torre, R.; Onggo, B.; Corlu, C.; Nogal, M.; Juan, A. The Role of Simulation and Serious Games in Teaching Concepts on Circular Economy and Sustainable Energy. Energies 2021, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, B.D.; Brauer, M. Gamification to prevent climate change: A review of games and apps for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Chu, S.K.W.; Shujahat, M.; Perera, C.J. The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 30, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krath, J.; Schürmann, L.; von Korflesch, H.F. Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 125, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, C.C. Design Variables of Attraction in Quest-Based Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, Boise State University, Boise, ID, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, T.W. Toward a Theory of Intrinsically Motivating Instruction*. Cogn. Sci. 1981, 5, 333–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Liu, J.-H.; Shou, W.-C. How Competition in a Game-Based Science Learning Environment Influences Students’ Learning Achievement, Flow Experience, and Learning Behavioral Patterns. J. Educ Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Meij, H.; Albers, E.; Leemkuil, H.H. Learning from games: Does collaboration help? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 42, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.; Connolly, T.M.; Hainey, T. The role of psychology in understanding the impact of computer games. Entertain. Comput. 2011, 2, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-7879-5140-5. [Google Scholar]

- Easley, J.A.; Piaget, J.; Rosin, A. The Development of Thought: Equilibration of Cognitive Structures. Educ. Res. 1978, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, P.; van der Spek, E.D.; van Oostendorp, H. Current Practices in Serious Game Research. Games-Based Learn. Adv. Multi-Sens. Hum. Comput. Interfaces Tech. Eff. Pract. 2009, 34, 232–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, K.; Carter, C.; Lee, J.; Tan, A.; de Prado, A.; Luscombe, D.; Briscoe, S. The Opportunities to Business of Improving Resource Efficiency; Final Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nußholz, J.L.K. Circular Business Models: Defining a Concept and Framing an Emerging Research Field. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linneberg, M.S.; Korsgaard, S. Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qual. Res. J. 2019, 19, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Parida, V.; Örtqvist, D. Product–Service Systems (PSS) business models and tactics—A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. The Performance Economy, 2nd ed.; Palgrave-MacMillan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrade, H.L. A Critical Review of Research on Student Self-Assessment. Front. Educ. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sitzmann, T. A meta-analytic examination of the instructional effectiveness of computer-based simulation games. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 489–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ayerbe, C.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Suárez-Perales, I.; Leyva-De La Hiz, D.I. Is It Possible to Change from a Linear to a Circular Economy? An Overview of Opportunities and Barriers for European Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Companies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieroni, M.D.P.; Blomsma, F.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Enabling circular strategies with different types of product/service-systems. Procedia CIRP 2018, 73, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Chiaroni, D.; Terzi, S. Circular business models in the European manufacturing industry: A multiple case study analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haaften, M.A.; Lefter, I.; Lukosch, H.; Van Kooten, O.; Brazier, F. Do Gaming Simulations Substantiate That We Know More Than We Can Tell? Simul. Gaming 2020, 52, 478–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui-Essoussi, L.; Linton, J.D. Offering branded remanufactured/recycled products: At what price? J. Remanuf. 2014, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, S.; Lee, J. The Effects of Consumers’ Perceived Values on Intention to Purchase Upcycled Products. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGee, J.; Sammu-Bonnici, T. Wiley Encyclopedia of Management: Strategic Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 12, ISBN 978-1-119-97251-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2020).

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | Cohort 3 | Cohort 4 | Cohort 5 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User group | Engineering students | Business students | Executives and entrepreneurs | Financial advisors | Mixed | |

| Moderation | Collectively | Per table | Per table | Per table | Per table | |

| Number of participants | 59 | 12 | 11 | 22 | 16 | 120 |

| Completed surveys | 22 | 12 | 7 | 11 | 11 | 63 |

| Response rate | 37% | 100% | 64% | 50% | 69% | 53% |

| Code | Cohort 1 (n = 43) | Cohort 2 (n = 34) | Cohort 3 (n = 15) | Cohort 4 (n = 19) | Cohort 5 (n = 19) | Total (n = 130) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External pressures | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 17 (13%) |

| Circular strategies | 14 | 20 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 54 (42%) |

| Business models and entrepreneurship | 25 | 17 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 78 (60%) |

| Themes & Subthemes | Number of Statements | Example Statements * |

|---|---|---|

| External Pressures | ||

| Resource depletion | 5 | Resources deplete quickly and they are hard to obtain after that. (E1.3) The minute the resources ran out you realise that you’ve got to be efficient and take better care of the available raw materials. (E1.4) |

| Uncertainty and shocks | 10 | Good intentions clashed with practical hurdles and market fluctuations. (E5.2) A more circular economy is more resistant to market changes. (E1.9) |

| Waste generation | 2 | The end-of-life waste grew rapidly and it was a shock to see so much waste piling up so quickly after one use. (E1.1) Less waste was created with the circular economy. (E1.2) |

| Circular strategies | ||

| Reduce material use | 8 | Circular economy can save lots of materials and reduce cost. (E1.15) |

| Resource efficiency | 11 | Improve the efficiency of the product. (E4.6) First you have to optimise existing manufacturing by reducing the use of basic materials to create additional cash flow. (E3.3) Resource efficiency increases had a smaller effect than I imagined. (E3.1) I realised that recycling is a good option only in an early stage, when resource efficiency is not too high. (E1.17) |

| Recycling | 16 | Recycled materials are very profitable in the lacking resources scenario. (E1.5) By going for recycling, you lose resources and you need to start production from scratch. (E2.5) |

| Remanufacturing | 9 | The smaller efforts required to re-introduce refurbished items compared to recycled. (E3.5) Recycling is good, remanufacturing is better. (E2.8) |

| Circular design | 8 | A product has to be designed in circular way beforehand. (E2.10) Products need to be adaptable. (E2.9) |

| Lifetime extension | 4 | If you go for pay-per-use, make sure you can extend the contract as many times as possible. (E2.18) |

| Multiple circular options | 4 | [There are] many different ways/strategies to ‘go circular’. (E3.7) |

| Keeping products in the loop | 3 | It’s more worthwhile to figure out how to keep products than make more. (E1.24) |

| Reverse logistics | 1 | Reverse Logistics can be a good strategy but with a more uncertain outcome. (E3.8) |

| Substitution | 1 | Biodegradability does not equal sustainability. (E5.8) |

| Business models and entrepreneurship | ||

| Investments and costs | 27 | It takes a lot of investment in the beginning. (E3.13) Investments are long term, don’t panic if you need to take on debt. (E2.24) |

| Cost reduction and profitability | 27 | A circular model can be more profitable than a standard model. (E2.25) |

| Long term planning and strategy | 22 | Long-term planning is key. If we risked early enough to invest in circular design, we would have saved a lot of materials and time wasted to recycling. (E1.22) |

| Operational complexity | 11 | It’s rather difficult to establish from the start an optimal circular economy strategy. (E4.15) A lot of work and effort is needed to change your system. (E5.16) |

| Pay-per-use | 10 | Direct sales are tempting, but [pay-per-use] contracts can be more valuable. (E2.23) The benefit is not experienced right away. It’s easiest to always sell and acquire cash early enough but then it does not pay off in the long term. (E1.28) |

| Taking risk | 9 | One should not hesitate to take risks when launching a start-up. (E4.17) Keep an expense deposit for emergencies. (E1.41) |

| Collaboration | 1 | Cooperation/partnership is key. (E4.16) |

| Marketing | 1 | Marketing is very important, but it is not embodied in the game. (E3.15) |

| Themes | Number of Statements | Example Statements * |

|---|---|---|

| Appreciation of Risk&RACE as a learning tool | ||

| Interesting | 12 | Great game that is challenging enough to trigger your interest and not too complicated so that your ideas about circularity will always result in good learning.” (L3.2) |

| Suitable as an introduction | 12 | Good tool to introduce business people and students to circular economy (L5.3) Good as an introduction to new concepts. (L5.4) |

| Fun and engaging | 11 | Useful and a lot of fun. (L2.6) |

| Need for complementing activities | 9 | Good as a starter. Requires more in-depth study for a true understanding. (L1.6) |

| Real world connection | 6 | “I think it is a very good game for simulating a business in real life.” (L2.3) |

| Hands-on | 5 | Very insightful, hands-on approach to learning some quite potentially confusing terms. (L1.4) |

| Prompting discussion | 4 | “A fun way to discover CE, opening debate and discussion between colleagues.” (L4.2) |

| Strong elements | ||

| Game mechanics and design | 31 | Layout was clear, topic was engaging. Friendly competitiveness made it fun. (S1.6) The look of the game was attractive and it is very tangible with the employees, the money and the investment cards. (S2.7) [I liked the] concept behind the game and the visualisation about how circular product leasing could work in practice (S3.2) |

| Strategic thinking | 19 | You have to take risks to make a profit. Strategy is very determining for the result. (S2.5) |

| Taking decisions | 15 | The importance of decision-making and the time pressure while doing that. I also found quite cool the connection to the real world. It allowed me to see better how decisions are made in companies and how they justify them, which I hadn’t understood clearly enough until now. (S1.17) |

| Educational elements | 15 | It improves knowledge of the various opportunities related to circular economy. (S4.4) |

| Interaction with other players | 10 | It was competitive, liked interacting with other players/teams, liked event cards and bonus cards. (S1.11) |

| Uncertainty created by scenario | 9 | I liked that there was a new event each round, which required the players to make decisions and try to anticipate what could happen in the future. (S1.2) |

| Real-world connection | 8 | Strategic and related to real life situations. I liked the event cards that gave each round a different spin. (S1.4) |

| Experimentation | 5 | We could take more risk, because of the unlimited cash and “it’s only a game”. (S3.1) |

| Weak elements | ||

| Complexity and rules explanation | 22 | It was too complicated so it took more time to really get involved. There are many too many rules and some of them aren’t obvious. It was also too long. (W4.10) |

| (Over)simplifications | 15 | Introduce storage costs, a predefined market demand that is not unlimited and maybe taxes, so working with debts is more profitable. (W3.7) |

| Game length | 9 | It was quite lengthy with many rules—could be simplified for a more enjoyable experience. (W1.8) |

| Moderation | 4 | Maybe some previous preparation especially for the game leader would be better as at the beginning we made a few mistakes because no one knew what the right thing was. It would be cool if a video was made with instructions that would be delivered to players prior to the game. That way some more time would be spared to play 4–5 extra rounds. (W1.16) |

| Too little player interaction | 3 | There could have been more interaction with the other teams. We did this ourselves, but I would have preferred it was more incorporated in the game. (W5.1) |

| Bookkeeping | 2 | Paper bookkeeping: an app would be better, for ecological reasons and to draw statistics afterwards. (W5.6) |

| Too limited debriefing | 1 | No learning tips at the end of the game. (W4.11) |

| None | 3 | None. (W4.2) OK for me (W4.6) |

| Intended Learning Goal | Achieved | Detailed Learning Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 1.1. The linear economy causes depletion of finite resources |

| 1.2. Resource constraints cause uncertainty, making companies vulnerable to unexpected events | ||

| 1.3. Linear economy creates a lot of waste | ||

| Yes | 2.1. There are various strategies to make a company more circular |

| 2.2. Resource efficiency saves on resources and costs | ||

| 2.3. Recycling is a valuable strategy to save resources, but still causes losses in value and materials | ||

| 2.4. Strategies that keep products in the loop, such as lifetime extension or remanufacturing require deliberate product design | ||

| Yes | 3.1. Shifting to a circular business model requires long-term planning and dedicated strategy |

| 3.2. Circular business models, such as pay-per-use, can be profitable, but focus on long term revenues | ||

| 3.3. Circular business models can be complex and capital-intensive to set up | ||

| 3.4. Entrepreneurship is about taking balanced risks |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manshoven, S.; Gillabel, J. Learning through Play: A Serious Game as a Tool to Support Circular Economy Education and Business Model Innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313277

Manshoven S, Gillabel J. Learning through Play: A Serious Game as a Tool to Support Circular Economy Education and Business Model Innovation. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313277

Chicago/Turabian StyleManshoven, Saskia, and Jeroen Gillabel. 2021. "Learning through Play: A Serious Game as a Tool to Support Circular Economy Education and Business Model Innovation" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313277

APA StyleManshoven, S., & Gillabel, J. (2021). Learning through Play: A Serious Game as a Tool to Support Circular Economy Education and Business Model Innovation. Sustainability, 13(23), 13277. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313277