Pathways to Improving Nutrition among Upland Farmers through Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions: A Case from Northern Laos

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Project Description

- Crop production—The project delivered intensive training on home gardening, and provided inputs to a few motivated pilot farmers who possessed sufficient land near household premises and labour to take care of the garden. Furthermore, a few beneficiaries who had sufficient resources—land, water, labour, and equipment—received inputs for establishing a greenhouse. The project provided training on fruits production and saplings of banana, mango and papaya trees, and also delivered rice and legumes production activities to some extent.

- Livestock production: Livestock activities comprised training on rearing livestock and inputs such as fence and fodders and paid vaccination.

2.3. Research Sites

2.4. Participants and Recruitment

- INI: Implementers at national level—interview

- INF: Implementers at national level—FGD

- IP: Implementers at the province level

- ID: Implementers at the district level

- IV: Implementers at village level

- PR-Private sector representative

- SR-School representative

- BI-Beneficiaries—interview

- BF-Beneficiaries—FGD

| Levels→ | National | Province | District | Village | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Method ↓ | Implementers (IN) | Implementers (IP) | Implementers (ID) | Private (PR) | Implementers—The VNT (IV) | School (SR) | Beneficiaries (B) | ||||||

| Phouko | Mokloy | Nam-Khong | Phonsa At | Phouko | Mokloy | Nam-Khong | Phonsa At | ||||||

| FGDs (n = 11) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| FGD participants | 4 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 16 | 11 | ||||

| Interviews (n = 34) | 1 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 (1 male) | 3 | 6 |

| Total (n = 101) | 5 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 17 |

2.5. Data Collection

- ENUFF Project learning brief No. 5, Nutrition-sensitive agriculture for improved dietary diversity, June 2021 [25]

- ENUFF project end line report, July 2020 [30]

- ENUFF Project learning brief No. 4, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) related determinants of under-nutrition, June 2020, [27]

- ENUFF Project learning brief No. 3, Promoting positive behaviours in nutrition through community volunteers, June 2020 [26]

- ENUFF Gender and Social Inclusion Report, November 2019 [31]

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Effects on Nutrition-Related Outcomes

3.1.1. Household Living Environment

“Some of the villages don’t have water access such as Phouko where the water access is very limited and some of the villagers don’t even have water access or too far from the water source or no equipment or money, then that’s just how it is. […] Their own usual habit, which is to open-defecate in the forest because they think it is convenient and that they don’t need to wash it.”[ID-3]

3.1.2. Care and WASH Practices

3.1.3. Dietary Practices

“[About] five food groups, sometimes they are not complete. […] When there are some, found some, we would have complete five groups but if not, there would only be about three groups.”[BI-2]

“No, I didn’t do the same [before and after the project] after the staff came and did the demonstration, I would often cook it.” [P1] “When they are 0–6 months, I would only give breastmilk, and after 6 months, I would cook rice porridge for the baby. […] Put in the rice, vegetable and sliced pork, also pumpkin, and a bit of salt.”[P3] [BF-3]

“[The consumption pattern] was like usual. The extra thing I added was when I had money, I would go and buy some fruits to eat. Of course, I increased my consumption of fruits and anything that would be beneficial for the baby. Buying Anne-Mum (maternal milk) as well. When I don’t have money then I don’t buy.”[BF-3]

3.1.4. Prevalence of Diseases

“Of course, it [reduction in diseases] has increased. Why? It is because, one, it has built our immune system to be better so that we don’t get sick, for our children to grow bigger and better. […] Our children get to attend school and they have no sickness.”[P2, IV-2]

3.1.5. Nutritional Status

“Previously, children were thin, malnourished. After the project came, they have access to vegetables and meat for their children to eat and when they did their height and weight measurement, and they passed […] Yes, for this we have seen from the results.”[P1, IV-4]

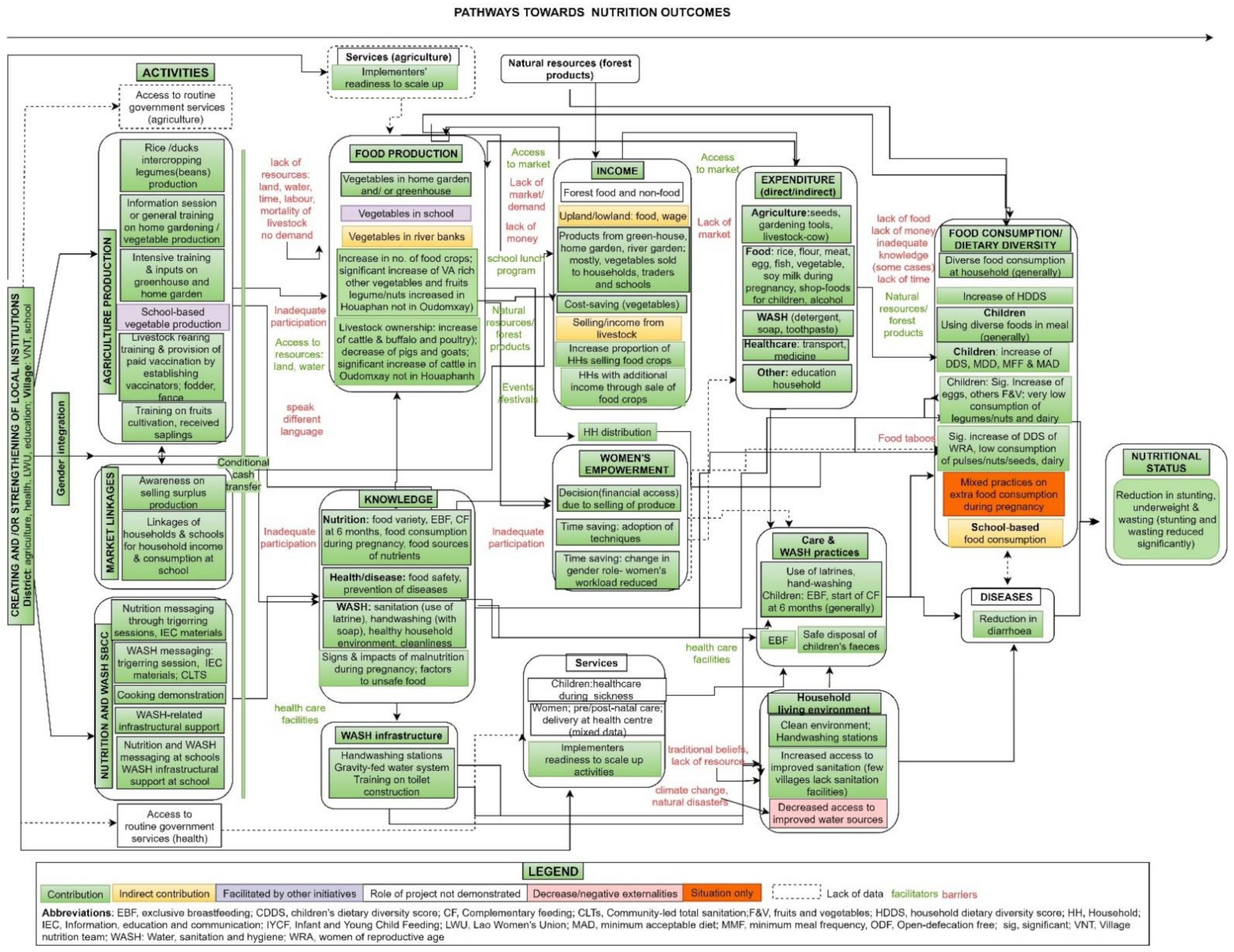

3.2. Pathways from NSA Interventions to Nutrition Outcomes

3.2.1. Food Production

“We all had a little bit before the project came. Only enough for family consumption” [P3] “Just a little one until the project came then we expanded and did more. It’s now enough for both consumption and for selling…” [P7] “Compared to last year, they look nicer…” [P4] “They came, trained us, and provided some seeds, hoe and watering can. They grow much better and can be sold and consumed by many families.”[P7] [BF-5]

“[Translator] she said she’s been raising them before ENUFF came but she didn’t have many and then after ENUFF came, they taught ways to take care of the livestock and so it has been improved.”[BI-7]

“Pigs and others are still okay. When we visited some of the villages, they all said their poultry died.”[ID_2]

“First of all, I have to make money for my children, secondly for our house, family and our livestock, plus the food is also dependent on me. However, I still do it [home garden] but only once or twice, only this dry season that I do not have enough time to do it yet. I still did it, sold two sets already, but I have not started the third set yet.”[BI-1]

“Since my vegetables didn’t look as nice, I went to see theirs and they told me the methods on how to grow them nicely with good quality and I would follow the methods that they’ve taught me. The result was that the products look better now… I was able to sell and consume some as well.”[BF-1]

3.2.2. Agricultural Income and Nutrition-Related Expenditure

“Before this, there were about 4–5 families that were selling vegetables and after the project was implemented, we could see that there are more families who are selling vegetables.” [P5] […]“More than 20 families [are selling]” [P5]. “About 50 families actually”[P1] [IV-2]

“Now it [income from selling vegetables] has increased to [double] […] [Particularly] the Chinese cabbage because nobody in the village has any. Only us. So, they would come and buy from us.”[BI-12]

“When I sell vegetables and earn some money, I use that money to buy meat or eggs if we feel like it.”[BI-14]

3.2.3. Nutrition and WASH-Related Knowledge and WASH Infrastructural Development

“They said for each day, we should consume six food groups or if we don’t have all the groups then at least 4 groups. If today we are eating vegetables, the [meal] should also include meat, potatoes, corns, etc. However, I am trying to consume at least four groups: vegetables, meat, bamboo shoots. […] If there is no rice, then we can use corns as a substitute, or potatoes or taros as a substitute. The vegetable oil replacement types are peanuts. Animal oil or peanuts. […] I just know when the project came.”[BI-13]

“Their own usual habit which is to open-defecate in the forest because they think it is convenient and that they don’t need to wash it.”[ID-3]

3.2.4. Women Empowerment

“Because they are based on the fact that if they depend on the women, they wouldn’t understand that well if I have to be truly honest. That’s how we are most of the time. They would just be like, okay, just let the men go because the women wouldn’t understand what they talk about. […] Most of the time it would be men.”[P2, IV-3]

“And after he went to the training, did he come back home and cook for your children or change the way you used to cook or prepare food for your children?” [interviewer] “He is a man, so he does not really know how to cook. Mostly for dinner, it is me and the kids who would cook for him.” [P1] “And he didn’t tell what to put and all?” [interviewer] “No, he didn’t.”[P1] [BF-6]

“We have vegetables in our home garden so if we want to eat some, we can just go and collect from our home garden and don’t need to go to the forest to find some. Save time so we can work for the family.”[P1, BF-3]

3.2.5. Strengthening the Local Institution

“Ever since the project came, Health office, Agriculture office and the Lao Women Union came to provide training on nutrition for the women and children under two so that they know how to cook properly for their children that will benefit them and for their growth development.”[IV-4]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kadiyala, S.; Harris, J.; Headey, D.; Yosef, S.; Gillespie, S. Agriculture and nutrition in India: Mapping evidence to pathways. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1331, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M.T.; Alderman, H. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 2013, 382, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, I.K.; Di Prima, S.; Essink, D.; Broerse, J.E.W. Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture: A Systematic Review of Impact Pathways to Nutrition Outcomes. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselow, N.J.; Stormer, A.; Pries, A. Evidence-based evolution of an integrated nutrition-focused agriculture approach to address the underlying determinants of stunting. Matern Child Nutr. 2016, 12 (Suppl. S1), 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruel, M.T.; Quisumbing, A.R.; Balagamwala, M. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: What have we learned so far? Glob. Food Secur. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S.; van den Bold, M. Agriculture, Food Systems, and Nutrition: Meeting the Challenge. Glob. Chall. 2017, 1, 1600002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao Statistics Bureau. Lao Social Indicator Survey II (LSIS II) 2017; Lao Statistics Bureau: Vientiane, Laos, 2018.

- Development Initiatives. 2020 Global Nutrition Report: Action on Equity to End Malnutrition; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nanhthavong, V.; Epprecht, M.; Hett, C.; Zaehringer, J.G.; Messerli, P. Poverty trends in villages affected by land-based investments in rural Laos. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 124, 102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Lao PDR. National Nutrition Strategy to 2025 and Plan of Action 2016–2020; Government of Lao PDR: Vientiene, Laos, 2015.

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017: Building Resilience for Peace and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-92-5-109888-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dyg, P.M. Understanding malnutrition and rural food consumption in Lao PDR. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 763–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, C.M.; Bech Bruun, T.; de Neergaard, A. Transitioning towards commercial upland agriculture: A comparative study in Northern Lao PDR. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 88, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broegaard, R.B.; Rasmussen, L.V.; Dawson, N.; Mertz, O.; Vongvisouk, T.; Grogan, K. Wild food collection and nutrition under commercial agriculture expansion in agriculture-forest landscapes. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 84, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siliphouthone, I.; Yasunobu, K.; Ishida, A. Analysis of Food Security among Rain-fed Lowland Rice-Farming Households in Rural Areas of Lao PDR A Daily Calorie Intake Approach. Trop. Agric. Dev. 2016, 60, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, I.K.; Essink, D.; Fumado, V.; Mridha, M.K.; Bhattacharjee, L.; Broerse, J.E.W. What Influences the Implementation and Sustainability of Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions? A Case Study from Southern Bangladesh. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouapao, L.; Insouvanh, C.; Pholsena, M.; Armstrong, J.; Staab, M. Strategic Review of Food and Nutrition Security in Lao People’s Democratic Republic; World Food Programme: Vientiane, Laos, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Mid Term Review National Nutrition Strategy Plan of Action 2016–2020: National Nutrition Commitee Secretariat; UNICEF: Vientiene, Laos, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.T. Status and prospects for livestock production in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2007, 39, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, K.; Case, P.; Jones, M.; Connell, J. Commercialising smallholder agricultural production in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Dev. Pract. 2017, 27, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammounheuang, K.; Saleumsy, P.; Kirjavainen, L.; Nandi, B.K.; Dyg, P.M.; Bhattacharjee, L. Section Two—Asia-Pacific Region—Sustainable Livelihoods for Human Security in Lao PDR: Home Gardens for Food Security, Rural Livelihoods, and Nutritional Well-being. Reg. Dev. Dialogue 2004, 25, 203. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S.; Poole, N.; van den Bold, M.; Bhavani, R.V.; Dangour, A.D.; Shetty, P. Leveraging agriculture for nutrition in South Asia: What do we know, and what have we learned? Food Policy 2019, 82, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNV. Converging for Improved Nutrition in Lao PDR. Enhanced Nutrition for Upland Farming Families (ENUFF); Technical Brief No. 1; Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2017; Available online: https://snv.org/assets/explore/download/enuff_-_converging_for_improved_nutrition.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2019).

- Scholz, R.W.; Tietje, O. Embedded Case Study Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SNV. Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture for Improved Dietary Diversity. Learnings from the ENUFF Project; Technical Brief No. 5; SNV Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2021; Available online: https://snv.org/assets/explore/download/ENUFF-learning-brief-5.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- SNV. Promoting Positive Behaviours in Nutrition through Community Volunteers: Using Community Volunteers to Reach Pregnant Women and Families with an Infant below 24 Months; Technical Brief No. 3; Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2020; Available online: https://snv.org/assets/explore/download/snv_enuff_learning_brief_3_-_online.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- SNV. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Related Determinants of Under-Nutrition; ENUFF Project Learning Brief No. 4, June 2020; Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2020; Available online: https://snv.org/assets/explore/download/snv_enuff_learning_brief_4_-_online.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- SNV. Enhancing Nutrition of Upland Farming Families: Baseline Report (February 2017), 54; Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2017; [Unpublished]. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SNV. Enhancing Nutrition Of Upland Farming Families: Endline Report (July 2020); Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2020; [Unpublished]. [Google Scholar]

- Malam, L. Enhancing Nutrition for Upland Farming Families (ENUFF) Gender and Social Inclusion Report Commissioned by SNV Laos with Funding from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation; Netherlands Development Organisation: Vientiane, Laos, 2019; [Unpublished]. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, L.; Schuster, M.; Torero, M. Quantity and quality food losses across the value Chain: A Comparative analysis. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, B.; Ambuko, J.; Papargyropoulou, E.; Schönfeldt, H.C. Guiding Nutritious Food Choices and Diets along Food Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdi, T.J.; Shah, S.U. Implementing Perennial Kitchen Garden Model to Improve Diet Diversity in Melghat, India. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 8, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushamuka, V.N.; de Pee, S.; Talukder, A.; Kiess, L.; Panagides, D.; Taher, A.; Bloem, M. Impact of a homestead gardening program on household food security and empowerment of women in Bangladesh. Food Nutr. Bull. 2005, 26, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, K.M.; Specio, S.E.; Shrestha, P.; Brown, K.H.; Allen, L.H. Nutrition knowledge and practices, and consumption of vitamin A-rich plants by rural Nepali participants and nonparticipants in a kitchen-garden program. Food Nutr. Bull. 2005, 26, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murty, P.V.V.S.; Rao, M.V.; Bamji, M.S. Impact of Enriching the Diet of Women and Children through Health and Nutrition Education, Introduction of Homestead Gardens and Backyard Poultry in Rural India. Agric. Res. 2016, 5, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olney, D.K.; Talukder, A.; Iannotti, L.L.; Ruel, M.T.; Quinn, V. Assessing impact and impact pathways of a homestead food production program on household and child nutrition in Cambodia. Food Nutr. Bull. 2009, 30, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olney, D.K.; Vicheka, S.; Kro, M.; Chakriya, C.; Kroeun, H.; Hoing, L.S.; Talukder, A.; Quinn, V.; Iannotti, L.; Becker, E.; et al. Using program impact pathways to understand and improve program delivery, utilization, and potential for impact of Helen Keller International’s homestead food production program in Cambodia. Food Nutr. Bull. 2013, 34, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Strategy for improved nutrition of children and women in developing countries. Indian J. Pediatr. 1991, 58, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelli, A.; Margolies, A.; Santacroce, M.; Roschnik, N.; Twalibu, A.; Katundu, M.; Moestue, H.; Alderman, H.; Ruel, M. Using a Community-Based Early Childhood Development Center as a Platform to Promote Production and Consumption Diversity Increases Children’s Dietary Intake and Reduces Stunting in Malawi: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, A.W.; Grant, F.; Watkinson, M.; Okuku, H.S.; Wanjala, R.; Cole, D.; Levin, C.; Low, J. Promotion of Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato Increased Vitamin A Intakes and Reduced the Odds of Low Retinol-Binding Protein among Postpartum Kenyan Women. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Nguyen, P.H.; Harris, J.; Harvey, D.; Rawat, R.; Ruel, M.T. What it takes: Evidence from a nutrition- and gender-sensitive agriculture intervention in rural Zambia. J. Dev. Eff. 2018, 10, 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keokenchanh, S.; Kounnavong, S.; Tokinobu, A.; Midorikawa, K.; Ikeda, W.; Morita, A.; Kitajima, T.; Sokejima, S. Prevalence of Anemia and Its Associate Factors among Women of Reproductive Age in Lao PDR: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey. Anemia 2021, 2021, 8823030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diana, R.; Khomsan, A.; Sukandar, D.; Riyadi, H. Nutrition extension and home garden intervention in posyandu: Impact on nutrition knowledge, vegetable consumption and intake of vitamin A. Pak. J. Nutr. 2014, 13, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Bold, M.; Kohli, N.; Gillespie, S.; Zuberi, S.; Rajeesh, S.; Chakraborty, B. Is There an Enabling Environment for Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture in South Asia? Stakeholder Perspectives from India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doocy, S.; Cohen, S.; Emerson, J.; Menakuntuala, J.; Jenga Jamaa, I.I.S.T.; Santos Rocha, J. Food Security and Nutrition Outcomes of Farmer Field Schools in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. Glob. Health Sci. Pr. 2017, 5, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Olney, D.K.; Pedehombga, A.; Ruel, M.T.; Dillon, A. A 2-Year Integrated Agriculture and Nutrition and Health Behavior Change Communication Program Targeted to Women in Burkina Faso Reduces Anemia, Wasting, and Diarrhea in Children 3–12.9 Months of Age at Baseline: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dulal, B.; Mundy, G.; Sawal, R.; Rana, P.P.; Cunningham, K. Homestead Food Production and Maternal and Child Dietary Diversity in Nepal: Variations in Association by Season and Agroecological Zone. Food Nutr. Bull. 2017, 38, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| SN | Village | Stunting [28] | Village Type [28] | District |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Namkhong | 60% | Type 1 Remote villages with extensive upland agriculture | Beng |

| 2 | Phonsa At | 71% | Type 2 Accessible villages with intensive commercial agriculture | Beng |

| 3 | Mokloy | 77% | Type 3 Subsistence-oriented villages with lowland agriculture (paddy) | Nga |

| 4 | Phouko | 61% | Type 1 Remote villages with extensive upland agriculture | Nga |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, I.K.; Essink, D.; Fumado, V.; Shrestha, R.; Susanto, Z.D.; Broerse, J.E.W. Pathways to Improving Nutrition among Upland Farmers through Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions: A Case from Northern Laos. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313414

Sharma IK, Essink D, Fumado V, Shrestha R, Susanto ZD, Broerse JEW. Pathways to Improving Nutrition among Upland Farmers through Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions: A Case from Northern Laos. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313414

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Indu K., Dirk Essink, Victoria Fumado, Ranjan Shrestha, Zefanya D. Susanto, and Jacqueline E. W. Broerse. 2021. "Pathways to Improving Nutrition among Upland Farmers through Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture Interventions: A Case from Northern Laos" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313414