Abstract

Generation Z has been online since the beginning, the online space is an integral part of their lives and personalities, and they make up about 30% of the world’s population. It is claimed that this youngest cohort is already the most numerous generation on the Earth. The most important holiday parameters for them are price and location. They want to explore new places and be active while abroad. The study examines the impact of safety concerns on changes in travel behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. We focused on members of Generation Z who study the Tourism and the Recreation and Leisure Studies programs, so these students have a positive attitude towards traveling. Data were collected via internal university systems at two periods of time connected to different stages of the pandemic outbreak. The sample was chosen randomly. The sample of Period 1 (n = 150) was composed in 2020, after the lifting of restrictions at the end of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Czech Republic. The sample of Period 2 (n = 126) was collected one year later, after the lifting of restrictions at the end of the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Czech Republic. Correspondence analysis was used for better understanding and representation. This is a unique research study on Generation Z in the Czech Republic and Central Europe. As a result of the contemporary demographic changes in the world, this generation will shape future travel demand. Hence, understanding these youngest travelers will be key to predicting how tourism trends could evolve in the next few years and how these could influence worldwide tourism. The respondents thought they would not change their travel habits in the next five years because of the pandemic. When Periods 1 and 2 were compared after one year of the pandemic, the respondents preferred individual trips to group trips and individual accommodation to group accommodation facilities. On the other hand, our findings revealed a significant increase in safety concerns related to changes in travel behavior when the above-mentioned periods were compared. The research contributes to mapping young people’s attitudes towards travel in the constrained and changing conditions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings help analyze the consumer behavior of the target group.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has had a devastating influence on the worldwide economy [1], politics [2], mortality rates [3], and tourism [4]. The first cases of this hazardous disease were reported in Wuhan on 31 December 2019. COVID-19 is manifested by respiratory difficulties (coughing, dyspnea), fever, muscle pain, and fatigue [5]. There have been many epidemics such as SARS, MERS, or Ebola in recent decades [6]. COVID-19, with such a disastrous effect on the economy and society, eclipsed all of these disasters [7]. In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic spread worldwide and significantly reduced almost all global tourism [8]. In early March 2020, there were already more than 1,400,000 cases of COVID-19 around the world [9]. On 11 October 2021, the Hopkins Institute registered 237,973,161 COVID-19 cases worldwide, with 4,853,836 deaths [10]. The United Nations Report for 2021 stated that the COVID-19 tourism collapse could have an enormous impact on global economies. A total tourism loss of more than $4 trillion is predicted for the years 2020 and 2021. It is expected that the worldwide recovery of tourism will be related to the uptake of COVID-19 vaccines globally [11].

Like other countries worldwide, the Czech Republic experienced a negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on life, the economy, and tourism. The first three cases of infection with novel COVID-19 were confirmed on 1 March 2020 [5]. In terms of healthcare, the Czech Republic managed the COVID-19 pandemic during the first wave successfully. Out of a total population of 10.7 million, on 26 May 2020, the Czech Republic had had 9229 COVID-19 cases, with 318 deaths [12]. However, the second wave that started in the fall of 2020 and the third wave in spring 2021 struck the population of the Czech Republic very hard. At the end of the third wave, on 12 May 2021, the Ministry of Health announced that there had been 1,650,760 cases of COVID-19, with 30,074 deaths [12].

Tourism is an important sector in the economy of the Czech Republic. In 2019, it contributed 2.9% of the total gross domestic product (GDP) [13]. In 2019, as many as 238,000 people were employed in the tourism industry. As a result of the multiplier effect with other tourism-related sectors, the total number is more than 370,000 employees, representing 7% of all economically active people in the Czech Republic [14]. Total consumption by tourists (incoming and domestic travel) was estimated at CZK 295 billion in 2018. Foreign travelers accounted for some 27.18 million overnight stays in the Czech Republic in 2019. They spent about CZK 124.1 billion there, which resulted in multiplied incomes into the public budgets in the order of CZK 49.7 billion [15]. Tourism provided greater prosperity and economic growth. The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly changed the positive development of tourism in the Czech Republic. Despite many national economic incentives and intensive regional campaigns that have helped maintain employment and support domestic tourism, the results indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profoundly negative effect on the tourism industry in the Czech Republic. The number of foreign tourists arriving in the Czech Republic has fallen dramatically. Many entities in the hotel and restaurant industry have shut down or struggled to survive. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a 51% decline in tourist arrivals and a loss of income of CZK 160 billion in the public budget [13]. According to professionals, the return to the pre-pandemic figures will not take months but years.

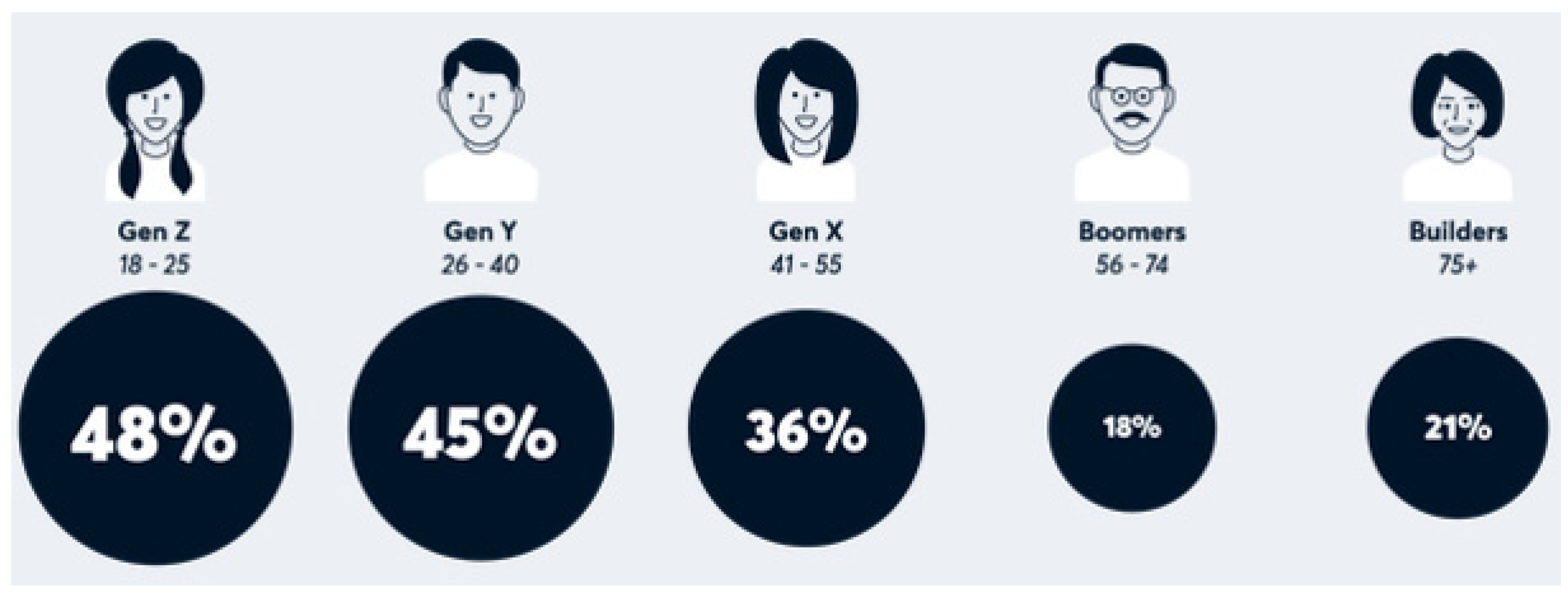

Numerous studies have examined the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism and hospitality industry. However, only a few papers have investigated the effect of COVID-19 and related safety concerns on travel behavior. At the same time, very little is known about the impact of COVID-19 on the travel behavior of Generation Z. This youngest cohort is claimed to be already the most numerous generation on Earth [16] and is defined as those born after 1995 [17]. Figure 1 shows the age of each generation and the percentages that indicate the impact that COVID-19 had on their quality of life. Generation Z (48%) and Generation Y (45%) were those most affected.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 and its impact on my life. Source: Fell [18].

Being in their teens and early twenties, up to a maximum of twenty-six, this life stage for Generation Z is typically characterized by education and study and socializing with friends after school or during breaks at university. Weekends are generally filled with sport and shopping, going out, or hanging out at a friend’s place. Generation Z’s goals and dreams are to do well in exams, spend quality time with friends, be environment-friendly, and work to save up for travel adventures. COVID-19 has changed this. Today, many members of Generation Z are being schooled at home or attending ZOOM lectures. They are canceling travel plans, social engagements, and even opportunities to see family members who are not living with them [18].

Generation Z grew up with new technologies and in a period of awareness about humankind’s negative impact on our planet (Table 1) [19]. Climate change, globalization, terrorism, and new technological devices have shaped their beliefs, motivations, and attitudes, and by extension, their travel behavior. According to the UNWTO [20] and ETC [21] reports, Generation Z perceives travel as an indispensable part of their life. Destination management organizations and other tourism stakeholders often ignore these young people because of their low levels of spending; however, they bring high profits for destinations worldwide. Generation Z are repeat visitors who like to discover new countries, contribute to the location they visit, and give more value to the destinations over time [20]. As a result of the world’s contemporary demographic changes, this generation will shape future travel demand [21]. Hence, understanding these youngest travelers will be key to predicting how tourism trends could evolve in the next few years and how these could influence worldwide tourism.

Table 1.

Contextual background for successive generations, 1940–2010.

For this reason, this manuscript focuses on Generation Z and particularly on students of Palacký University Olomouc and the College of Polytechnics Jihlava, two major hubs of higher education tourism study in the eastern part of the Czech Republic, Moravia. The aim of this paper is to examine the impact of concern for safety on changes in travel behavior among these young people during two different periods of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Specifically, the objectives of this study are to examine: (i) the impact of travel on quality of life, (ii) the intention to travel during and after the pandemic outbreak, (iii) safety concerns, and (iv) changes in travel behavior.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impact of Travel on Quality of Life (QOL)

Vacations are a time to gain new experiences, see new sights, and be away from one’s usual environment. Several studies have discussed the impact of vacations on an individual’s QOL [22,23,24,25,26]. In the recent literature, we can find more than 100 definitions and models of QOL [27]. One of the first definitions is from Cutter [28], who specified QOL as ‘an individual’s happiness or satisfaction with life and environment including needs and desires, aspirations, lifestyle preferences, and other tangible and intangible factors which determine overall well-being.’ According to the WHO [29], QOL is ‘individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and concerning their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.’ Barreto Torres et al. [30] describe QOL as a condition that derives from human well-being and as a tool that allows the extent to which human potentialities can be exercised at their fullest to be assessed, considering the environmental conditions in which individuals and groups find themselves and the opportunities provided by them. As we can see, the broad dimension of quality of life is difficult to describe in a unified manner. Neal et al. [31] first conducted research related to the importance of vacation experiences for QOL. Their results showed that tourists’ overall life satisfaction depends on satisfaction with the services provided, for example, with accommodation, gastronomy, or the type of leisure trip. Sirgy et al. [26] state that travelers’ memories originating from their latest vacation influence satisfaction in 13 domains of life (i.e., leisure life, social life, family life, health and safety, working life, cultural life, love life, travel life, spiritual life, culinary life, financial life, and arts, and culture) that affect their overall life satisfaction. Oppermann and Cooper [32] highlighted that, in comparison to consuming material goods, engaging in memorable and meaningful experiences such as a vacation can have a more significant impact on subjective well-being. Vacations typically result in positive impacts on well-being and personal relaxation [33]. They are also mentally and physically beneficial [34]. However, research has also shown that the influence of vacation memories on overall life satisfaction is not always positive and can vary considerably [35]. Vacation memories are not essential to everyone [22,36]. It depends on the stage in everyone’s life, level of importance of travel, and some other background factors. In general, going on vacation is, for many people worldwide, an indispensable part of their quality of life [37].

Seeman [38] states that meeting relatives and friends as part of the travel can be beneficial for one’s well-being and physical health. Fritz and Sonnentag [39] note that taking a vacation increased work efficiency after returning to work. Durko and Petrick [40] point out that travel strengthens family bonds and enhances communication. Taking a vacation supports many life domains in a positive way, such as family life, leisure life, working life, marital life, etc. [41]. Many other studies have shown that travel and taking a vacation provide many well-being and health benefits [22,37,42,43] and have a positive impact on the QOL of many people worldwide [22].

2.2. Safety Concerns

Safe travel is one of the key criteria shaping many visitors’ travel patterns [44]. It has been suggested that the perception of risk is one of the most significant concerns in global tourism because of the possibility of the safety of travelers and local communities being endangered [45]. We can define risk perception as the personal evaluation of the risk of a threatening situation based on severity and its features [46,47]. Taking into account the fact that the pandemic is extremely dangerous for one’s health, traveling to destinations with a high number of infected people is surmised to be a safety concern for many travelers.

Ensuring safety is a vital vacation planning objective [48], mainly because of several unpredictable problems related to going to unknown locations. The risk related to health safety is one of the most significant criteria in the selection of a desired destination and the selection of tourism services [49]. The pandemic has changed tourists’ concerns about safety related to their vacation. Travelers are more conscious of safety, health, and hygiene. Visitors have safety, health, and hygiene concerns in accommodation facilities, restaurants, recreation areas, and even in public transport [50]. Healthcare and sanitary precautions have grown in importance. Tourists carefully monitor destinations’ measures concerning cleanliness, hygiene, and safety and the level of possible medical care [51].

In general, pandemics of any sort have a direct impact on visitors’ decision-making process, visiting destinations, hotels, and types of leisure trip [52,53,54]. Whether real or perceived, the presence of risks affects visitors’ itinerary and behavior [55,56,57]. The pandemic has created colossal health and safety concerns [58,59,60], which have a great influence on the perception of the risk posed by travel. The more unpredictable and dangerous to health the situation is, the greater the perception of risk [61,62]. Tourists are more likely not to visit destinations that have extreme safety risks [63,64] and instead go to safe countries or regions [54,65]. Nonetheless, there were many pandemics around the world; hence, the risks related to COVID-19 are among the most enormous in the history of tourism [66]. A less devasting impact in recent history was caused by the SARS pandemic in 2004, which caused a 65% decrease in visitor arrivals in South and Southeast Asia [67].

Several studies have demonstrated that safety concerns and perceived risk had an impact on the decision-making process as to whether to go or not go, where potentially to spend a vacation [54,57,60,68,69], and even influenced the intention to come back to a favorite destination [62,64,70]. The results of these studies are supported by Neuburger and Egger [71], who identified that the perception of risk and willingness to react in a flexible way have a direct impact on the intention to travel.

2.3. Intention to Travel

We can observe that tourists’ safety concerns and risk tolerance significantly influence their decision-making process. Safety concerns and the perceived risk of traveling are directly associated with the intention to change one’s itinerary, visit a specific country, or not travel to a particular location [54,64,72,73]. The intention to travel can be defined as one’s intention to go on a trip or a commitment to doing so [74]. Karagöz et al. [75] state that the intention to travel results from an individual’s mental process that influences their actions and changes motivation into behavior or action. The nature of past travel experiences may influence tourists’ travel intentions. Existing studies demonstrate that risks affect tourists’ overall travel intentions [76,77] concerning domestic and international travel [78]. The COVID-19 pandemic confirmed that after any crisis or pandemic, supporting domestic tourism is crucial. Domestic tourists are expected to be among the first to travel again and reignite demand [79]. Tourists feel safer when traveling shorter distances and are familiar with all safety precautions [80].

Wachyuni and Kusumaningrum [81] point out that respondents from Indonesia claimed positive attitudes toward outgoing tourism, but travel intentions altered because of pandemics. Nazneen et al. [58] highlighted that visitors’ perception of risk influenced the travel decisions of Chinese tourists in a negative way. The perception of the risk posed by COVID-19 and safety concerns increased the travel intentions of South Korean visitors for an individual and cashless vacation regarding safety measures and health-protective vacation behavior [66].

2.4. Travel Behavior

Several COVID-19 pandemic studies demonstrate a change in common travel behavior. Safety concerns and fear of infection significantly influence travel behavior, particularly for transit, and depend on the infected location and demographic data [82,83]. People travel less and use more active forms of mobility and cars than public transport [84,85]. Tourists’ risk perception is higher for all trips. They do not visit destinations with a medium-to-high risk [86]. The pandemic has an influence on tourists´ behavior, destination selection, and type of accommodation. Tourists observe hygiene measures carefully, avoid mass destinations and events with large numbers of people, and take into account countries’ real-time safety situations [87]. Hygiene, cleanliness, and safety are considered to be key decision-making priorities, as demonstrated by several studies [81,88]. Because of pandemics, travelers change destinations, their choice of accommodation, and type of leisure trip, and some even choose not to travel at all [89].

Post-COVID tourism will be dependent on future health and safety protocols at destinations. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the hospitality sector and tourists’ behavior has been investigated in several studies. However, there is a lack of papers that studied the impact of safety concerns on changes in travel behavior from a retrospective point of view among the new future leading segment of travelers—Generation Z. The present research aims to fill this recognized gap.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of this article is to examine the impact of safety concerns on changes in travel behavior among Generation Z (students of Palacký University Olomouc and the College of Polytechnics Jihlava) during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Data collection took place via an internal university system over two periods of time connected to different stages of the pandemic. The sample was randomly selected (quota sampling) by approaching all students of the Tourism and the Recreation and Leisure Studies programs. Programs dedicated to tourism are vocationally oriented and strongly practice-oriented. Students take a range of professional courses focusing on tourism businesses (hospitality and travel agencies) and destination management. Graduates of these programs mainly work in services (hotels, restaurants, castles, museums, etc.) and at various levels of destination management. The sample of Period 1 (n = 150) was gathered from May 29 to July 4, 2020, after the lifting of restrictions at the end of the first wave of COVID-19. At the beginning of Period 1, on May 29, 2020, the Czech Republic had registered just 9229 COVID-19 cases, with 318 deaths [12]. The sample of Period 2 (n = 126) was collected one year later, from May 12 to June 26, 2021, after the lifting of restrictions at the end of the third wave of COVID-19. The situation at that time was much more devastating. The Czech Republic announced on May 12, 2021 that there had been 1,650,760 cases of COVID-19, with 30,074 deaths [12]. The basic sample consisted of 452 students (College of Polytechnics Jihlava) + 294 (Palacký University Olomouc), which was sufficient for our study. From the basic sample of 746 students, a sample of 150 respondents was selected during Period 1 (n = 83; 55.33%—College of Polytechnics Jihlava and n = 67; 44.67% Palacký University Olomouc). During Period 2, from the basic sample, 126 respondents were selected; the basic sample was (n = 61; 48.42%—College of Polytechnics Jihlava and n = 65; 51.58% Palacký University Olomouc). This study contributes a novel perspective on the development of safety concerns and travel behavior among Generation Z at two different stages of the spread of the pandemic.

On the basis of the literature, this study seeks to understand how young people perceive safety related to changes in their travel behavior. Today, several studies are focusing on different levels of risk when traveling [71,87]. In our study, we focused specifically on young people, i.e., Generation Z. In connection with the research goal, the following research questions were posed:

- –

- What has been the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel and quality of life?

- –

- What was the impact of safety concerns on changes in intention and travel behavior over time during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic and one year later? Is there a greater emphasis on safety and hygiene in travel?

We also formulated two hypotheses as well as alternative hypotheses for which we expected that the individual impacts would be essentially the same in terms of their importance for both periods.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

The respondents gave equal weight to the impact of restrictive measures on their quality of life in both periods examined.

Hypothesis 1A (H1A).

The respondents did not give equal weight to the impact of restrictive measures on their quality of life in both periods examined.

Hypothesis 20 (H20).

The respondents perceived protective measures concerning travel safety risks as equally important in both periods.

Hypothesis 2A (H2A).

The respondents perceived protective measures concerning travel safety risks as differently important in both periods.

This article contributes to a novel perspective on safety concerns and changes in the travel behavior of Generation Z at two different stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study was conducted using a quantitative research design. The survey instrument was a self-administered questionnaire consisting of four sections (see above). Using a five-point Likert scale, all items were ranked from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The constructs included the impact of travel on quality of life, which was initiated with two items. Intention to travel was measured with three items from previous studies [71,83,87]. Safety concerns also consisted of three items. The last section, about changing travel behavior, used seven items adapted from the literature [87,89]. All items were modified and formulated in the Czech language to fit the context of this study.

For the evaluation, the Statistica 13 EN software and SPSS 22 statistical program were used. Cronbach’s Alpha (α), average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were used to measure the reliability of the scales used in this study (Table 2). For better understanding, we also used an analysis method, correspondence analysis (CA). Using this CA graphic tools, it is possible to describe an association of nominal or ordinal variables and obtain a pictorial representation of a relationship in multidimensional space. The analysis provides further evidence that correlations exist between variables.

Table 2.

The sample of participants.

CA is a multivariate statistical technique. It is conceptually similar to principal component analysis but applies to categorical rather than continuous data. Like principal component analysis, it provides a means of displaying or summarizing a set of data in a two-dimensional graphical form [90].

All data should be non-negative and on the same scale for CA to be applicable, and the method treats rows and columns equivalently. It is traditionally applied to contingency tables. CA decomposes the chi-squared statistic associated with this table into orthogonal factors. The distance between single points is defined as a chi-squared distance. The formula gives the distance between the i-th and i′-th rows:

where rij are the elements of the row profiles matrix R and cj corresponds to the elements of the column loadings vector cT, which is equal to the mean column profile (centroid) of the column profiles in multidimensional space. The distance between the columns j and j′ is defined similarly; weights correspond to the elements of the row loadings vector r and sum over all rows. In correspondence analysis, we observe the relation between single categories of two categorical variables. This analysis results from the correspondence map introducing the axes of the reduced coordinates system, where single categories of both variables are displayed in graphic form. This analysis aims to reduce the multidimensional space of row and column profiles and save original data information as far as possible. Each row and column of the correspondence table can be displayed in a c-dimensional (or r-dimensional, respectively) space with coordinates equal to the values of the corresponding profiles. The row and column coordinates on each axis are scaled to have inertias equal to the principal inertia along that axis: the principal row and column coordinates [91,92].

4. Results and Discussion

The samples of the above-mentioned periods were derived from the students of Palacký University Olomouc and the College of Polytechnics Jihlava during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. In this study, 276 respondents participated in two periods; 15% were students of distance studies. The complete sample consisted of 24.01% men and 75.99% women from the Czech Republic. Women were more represented in the research population as the respondents were students of study programs in which a high proportion of women traditionally study. More detailed information is provided in Table 2.

Most of the respondents were from the Olomouc (21.01%) and Vysočina (21.01%) regions, as these two regions are home to the universities involved in the study. Furthermore, respondents from the Moravian–Silesian region (11.96%), the Zlín region (9.42%), and the South Moravian region (7.25%) were further well-represented groups. A small set of respondents were international students (2.54%), mainly from Slovakia and the Russian Federation.

AVE and CR showed better construct values than the required 0.50 for AVE and 0.70 for CR [93]. Our results are identical to the findings of other studies around the world. Similar values were achieved by the study of Neuburger and Egger that conducted research in the DACH region, which comprises Germany, Austria, and Switzerland [71]. There are different studies about the acceptable values of Alpha, ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 [94,95]. However, we must note that some authors indicated that Alpha has a threshold or threshold value as an acceptable, sufficient, or satisfactory level. It was generally perceived as ≥0.70 (five instances) or >0.70 (three instances), although one article more vaguely referred to acceptable values of 0.70 or 0.60 [96,97]. In particular, the number of items tested, the relationship of the items, and the size affect the Alpha value [93]. A low value of Alpha could be due to a low number of questions, poor inter-relatedness between items, or heterogeneous constructs. In our study, the values of α = 0.65 (impact of travel on quality of life), α = 0.60 (intention to travel), and α = 0.68 (safety concerns) were found. We suppose that these values can be seen as acceptable because of the low number of items [98]. On the other hand, if the Alpha value is too high, some items are redundant as they test the same question but in a different guise. A maximum Alpha value of 0.90 has been recommended [99]. Our highest value of Alpha reached α = 0.79.

The participants in our research were students of the “Tourism” and “Recreation and Leisure Studies” study programs. This research sample is quite specific because traveling was the point of interest for all respondents. That was one of the reasons why we assumed that travel would be of great importance to them.

For verification, we used ANOVA tests. The established p-value (p = 0.000) is lower than the selected value; therefore, at the significance level of 5%, we reject H0. Given the absence of travel options and the closure of accommodation facilities and restaurants, the respondents became even more aware of the positive impact of travel on their quality of life in the second period. We also tested the alternative hypothesis that the number of respondents perceived protective measures concerning the travel safety risk as equally important in both periods using the ANOVA test. The established p-value (p = 0.000) is lower than the selected value. Therefore, at the significance level of 5%, we reject this hypothesis. It can be stated that there is a variance between the safety concerns between the two periods (Table 3).

Table 3.

Variables and number of categories.

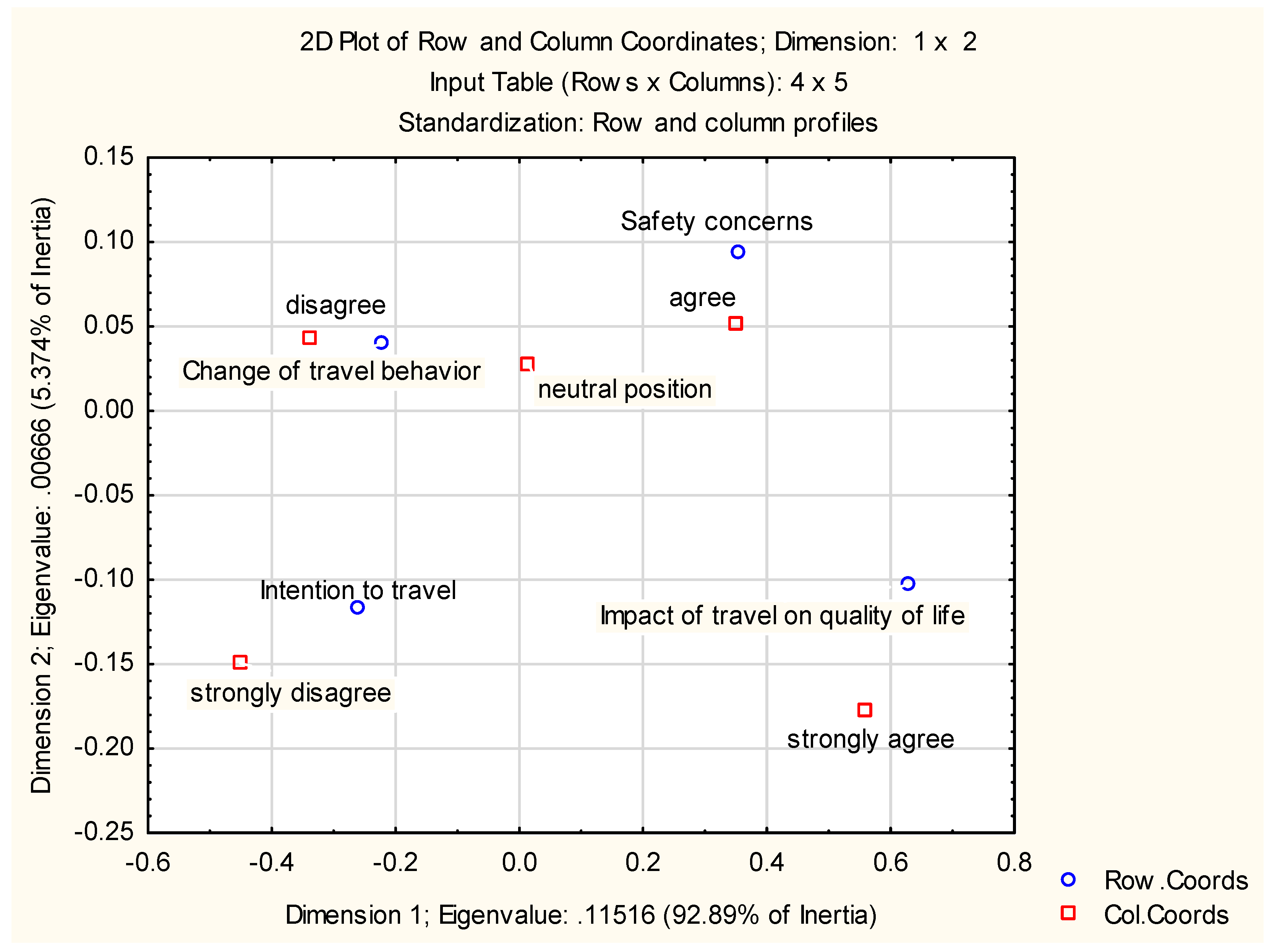

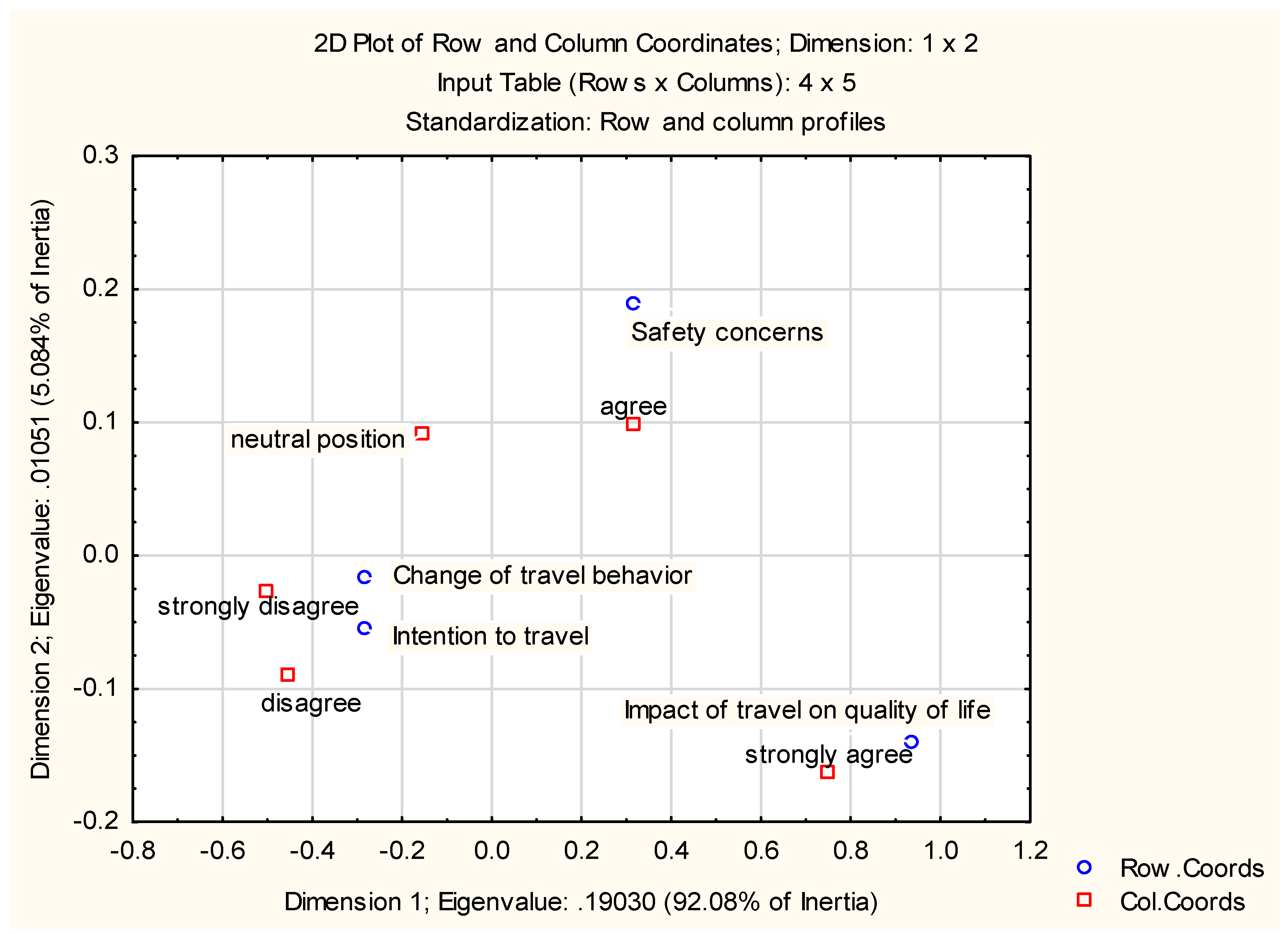

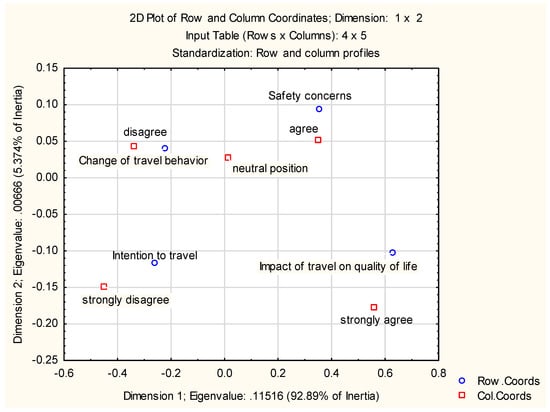

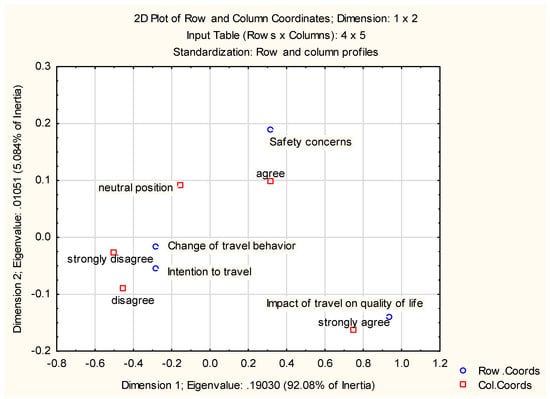

In general, compared to the views of our sample in Periods 1 and 2, we can state that the impact of travel on quality of life was very high. Most respondents realized (especially in Period 1, when hotels, restaurants, and other services were closed) that traveling around the Czech Republic and abroad is extremely important for their personal happiness and significantly improves their quality of life. On the other hand, the willingness to change travel behavior as a result of restrictions because of COVID-19 was very low, which is confirmed in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Respondents’ views on tourism and the COVID-19 pandemic (Period 1). Source: authors’ elaboration.

Figure 3.

Respondents’ views on tourism and the COVID-19 pandemic (Period 2). Source: authors’ elaboration.

The data showed (Table 4) that the severity of COVID-19 in Period 1 was understood and perceived as average. The lowest median values were in the sections “Intention to travel” (2.63 with SD 1.13) and “Change of travel behavior” (2.70 with SD 1.10). In contrast, the most significant mean values were found in the section “Impact of travel on quality of life” (3.66 with SD 0.78). Compared to Period 2, slight increases in individual areas can be observed. In the section “Impact of travel on quality of life”, there was a significant increase in mean values (from 3.66 with SD 0.78 to 4.21 with SD 0.78).

Table 4.

Reliability and mean values.

Regarding the impact of travel on quality of life, we can state that the respondents have become even more aware of the positive effects of travel on their quality of life. The opportunity to travel was important to them in Period 1. After one year of travel being limited and restricted, they perceived the positive effects on their quality of life significantly more. We note the same trend in the claim that traveling in the Czech Republic and abroad is extremely important for their personal happiness and dramatically improves the quality of their lives. During research Period 1, they agreed with this statement. However, after one year (Period 2), they agreed strongly.

The respondents were careful to think about their intention to travel. They disagreed with the statement that, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they would not be able to travel for at least one year. During Period 2, they were more neutral in their opinions. Furthermore, they disagreed that they would spend their vacations in the Czech Republic more often in the next five years. During Period 2, they were more neutral, and they were not sure about traveling abroad. We can note the progress in understanding the new situation and travel restrictions around the world, and they are still looking for some travel choices. Domestic tourism is the first option for Generation Z. The respondents intended to travel in 2020 and 2021, primarily in the Czech Republic. They agreed with this statement. The findings are in line with the results of similar studies around the world [80,87,88].

Focusing on the safety concerns during Period 1, the respondents agreed, similarly to a Bulgarian research study [87], that they were thinking more about selecting their destination and the possible health risks. The research shows similar results in Period 2; the selection of the destination was even more critical. After one year of the COVID-19 crisis, the respondents, contrary to the study [87], did not agree that they would avoid countries with a high number of infected people. On the other hand, Generation Z, independently of Period 1 or 2, agreed that they would use accommodation facilities where all hygienic measures are respected. The increased significance of safety and hygiene is underlined in other research papers as well [81,88,89].

The respondents thought they would not change their travel habits in the next five years because of the pandemic. Compared to Periods 1 and 2, after one year of the pandemic, the respondents preferred individual trips to group trips and individual accommodation (such as AirBnB) to group accommodation facilities.

Interestingly, the respondents did not think they would be concerned about attending events with many people. They also disagreed that they would limit their visits to restaurants, bars, and discos.

Traveling by public transport is also one area where Generation Z in the Czech Republic, in contrast to other research [99], did not want to change their behavior because of the pandemic. The respondents prefer to use air transport for traveling. They disagreed that they would limit their flying because of the various restrictions. They were stricter in Period 2, and they disagreed with these statements.

It is evident that tourism has not yet recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic. As early as the end of 2019, there were reports of COVID-19 in Asia, but most people did not focus on the news for too long because it did not concern them. An even bigger surprise and finding was that this pandemic spread to all countries of the world. One of the sectors most affected was tourism, as there were restrictions on travel for tourism or even within regions; borders were closed. The findings revealed a significant impact of safety concerns on travel behavior among Generation Z in the Czech Republic. We can state that Generation Z intends to travel despite concerns regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, and only a tiny part of the respondents hesitated to buy tickets for destinations abroad. Unlike other young travelers from other countries, the respondents were not very afraid. However, the COVID-19 pandemic still affects them while traveling—they were most concerned about various anti-pandemic measures.

Our study revealed some key messages that could be valuable for policymakers and destination management organizations, particularly in the post-COVID era. These findings could help them better optimize their tourism strategy and efficiently target Generation Z’s leading future tourism segment.

To sum up, (1) Generation Z is eager to travel. Because of the absence of travel opportunities and shutdown of accommodation facilities and restaurants, Generation Z has become even more aware of the positive effect of travel on its quality of life. Generation Z misses going on vacation and intends to travel. It is good news for destinations and tourism policymakers. There are tendencies to prefer domestic tourism in the short term, but in the long-run context, outgoing travel should be highlighted again. (2) Generation Z will not change its travel habits. Generation Z would like to travel in the future the same way as before the pandemic. However, there is a trend towards individual travel and small accommodation facilities instead of traveling in groups. (3) Safety concerns will still play a critical role in the decision-making process. Generation Z will think carefully about the choice of destination and possible health risks. Its members will choose accommodation facilities where they can expect that all hygiene measures will be respected. (4) Even destinations with a high number of infected people have good chances of being visited by Generation Z. Generation Z is willing to visit destinations even if the country had an increased number of COVID-19 infections. However, policymakers and destination management organizations should communicate their efforts concerning combating the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, the destination needs to observe strict health and safety protocols, which will help regain the confidence of Generation Z. (5) Generation Z is not afraid to go to restaurants, bars, discos, and even significant events or travel by public transport and by plane. Generation Z intends to have fun, but as mentioned before, there is a necessity that all health and safety rules at its destinations will be observed.

This study has its limitations, and therefore our research cannot be generalized.

Firstly, we focused on Generation Z, but this was the goal of our research. Currently, this generation is the most numerous globally, which will influence shaping future tourism and have practical implications for tourism policymakers. It is the first study focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic and Generation Z’s perceptions of travel behavior in Central Europe.

Secondly, the small sample of respondents limits the present study. It was only focused on two Czech universities (Palacký University and the College of Polytechnics Jihlava). In our opinion, the study’s main limitation is that it focuses on young people in one country only. Additionally, we must state that this is a sample obtained through universities’ information systems, and thus it cannot represent the entire population, especially Generation Z. On the other hand, students who focus on tourism were contacted, and therefore, we know their motivation, requirements, etc. Compared to the study by Sanchez [64], the questionnaire was not distributed through social networks and travel forums. There is a greater probability of anonymization and distortion of the result than in our sample, which involved tourism students. We have to state that this results in a relatively lower number of respondents, even though the principles of quota sampling were followed. The results of our study are confirmed by the European Travel Commission [21], especially concerning QOL and safety concerns. Our findings also confirm the Generation Z survey, which states that traveling is essential for personal development (US 69%, UK 67%, CN 60%, and DE 50%). Analyzing the primary motivations for choosing a European leisure destination shows that cost and safety dominate the decision-making process. With relatively little travel experience (given their age), it also reveals that safety and security are important to Generation Z (CN 53%, US 42%, UK 38%, and DE 34%). In addition to the theoretical basis, there is also a practical benefit for DMOs, tourism policymakers, etc.

Finally, we want to investigate other Czech universities and universities abroad and compare these data with this study. In our future research, we would also like to focus on the older generation regarding productive age, seniors, and young families with children.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.; methodology, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; software, P.S. and I.L.; validation, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; formal analysis, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; investigation, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; resources, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; data curation, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; writing—review and editing, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; visualization, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; supervision, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; project administration, M.R., P.S., and I.L.; funding acquisition, M.R., P.S., and I.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the Czech Science Foundation under reg. no. 18-24977S and other grants from the College of Polytechnics Jihlava under reg. no. 1170/26/451 and 1170/26/452.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Faculty of Physical Culture University Palacky and College of Polytechnics Jihlava (protocol codes 92/2020, 92/2021 and date of approval October 21, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Battistini, N.; Stoevsky, G. Alternative Scenarios for the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Economic Activity in the EURO Area. Economic Bulletin Boxes. March 2020. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2020/html/ecb.ebbox202003_01~767f86ae95.en.html (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- McKibbin, W.; Fernando, R. The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios. Asian Econ. Pap. 2020, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Wang, D.; Hallegatte, S.; Davis, S.J.; Huo, J.; Li, S.; Bai, Y.; Lei, T.; Xue, Q.; Coffman, D.; et al. Global Supply-Chain Effects of COVID-19 Control Measures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (Ed.) UNWTO World Tourism Barometer May 2020 Special Focus on the Impact of; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2020; ISBN 978-92-844-2181-7. [Google Scholar]

- Komenda, M.; Bulhart, V.; Karolyi, M.; Jarkovský, J.; Mužík, J.; Májek, O.; Šnajdrová, L.; Růžičková, P.; Rážová, J.; Prymula, R.; et al. Complex Reporting of the COVID-19 Epidemic in the Czech Republic: Use of an Interactive Web-Based App in Practice. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumov, N.; Varadzhakova, D.; Naydenov, A. Sanitation and Hygiene as Factors for Choosing a Place to Stay: Perceptions of the Bulgarian Tourists. Anatolia 2021, 32, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, M.A.R.; Park, D.; Lee, M. How a Massive Contagious Infectious Diseases Can Affect Tourism, International Trade, Air Transportation, and Electricity Consumption. The Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) in China (19 February 2020). Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3540667 (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Worldometers Coronavirus Worldwide Graphs. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/worldwide-graphs/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Hopkins Institute. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- United Nations. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditcinf2021d3_en_0.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Ministry of Health. Trendový Profil Epidemiologické Situace. Available online: https://onemocneni-aktualne.mzcr.cz/covid-19 (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Ministry for Regional Development. Krizový Akční Plán Cestovního Ruchu v České Republice 2020–2021. Available online: https://www.ahrcr.cz/novinky/krizovy-akcni-plan-cr-v-cr-2020-2021 (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Tourism Forum Czech Republic. Nad Cestovním Ruchem Se Stahují Mračna. Available online: https://forumcr.cz/nad-cestovnim-ruchem-v-cesku-se-stahuji-mracna (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- The Czech Association of Hotels and Restaurants. Coronavirus and Its Anticipated Impact on Tourism in the Czech Republic. Available online: https://www.ahrcr.cz/en/news/coronavirus-and-its-anticipated-impact-on-tourism-in-th-czech-republic (accessed on 28 February 2020).

- Lee, J.M.; Wei, L. Gen Z Is Set to Outnumber Millennials within a Year. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-20/gen-z-to-outnumber-millennials-within-a-year-demographic-trends (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Tourism Cities, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-0-429-24460-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, A. The Substantial Impact COVID-19 Has Had on Gen Z. Available online: https://mccrindle.com.au/insights/blog/the-substantial-impact-covid-19-has-had-on-gen-z/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Francis, T.; Hoefel, F. The Influence of Gen Z—The First Generation of True Digital Natives—Is Expanding. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/consumer-packaged-goods/our-insights/true-gen-generation-z-and-its-implications-for-companies (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- UNWTO. The Power of Youth Travel. Available online: www.unwto.org (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- ETC. Study on Generation Z Travelers. Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/study-on-generation-z-travellers/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Dolnicar, S.; Yanamandram, V.; Cliff, K. The Contribution of Vacations to Quality of Life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nawijn, J. Determinants of Daily Happiness on Vacation. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J. Happiness through Vacationing: Just a Temporary Boost or Long-Term Benefits? J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearce, P. Relationships and the Tourism Experience: Challenges for Quality of Assessments. In Handbook of Tourism and Quality-of-Life Research: Enhancing the Lives of Tourists and Residents of Host Communities; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Kruger, P.S.; Lee, D.-J.; Yu, G.B. How Does a Travel Trip Affect Tourists’ Life Satisfaction? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Nyaupane, G.P. Exploring the Nature of Tourism and Quality of Life Perceptions among Residents. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, A. A Geographer’s View on Quality of Life; Commercial Printing Inc.: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Measuring Quality of Life; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto Torres, L.D.; Asmus, G.F.; da Cal Seixas, S.R. Quality of Life and Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1333–1340. ISBN 978-3-030-11351-3. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, J.; Sirgy, M.J.; Uysal, M. The Role of Satisfaction with Leisure Travel/Tourism Services and Experience in Satisfaction with Leisure Life and Overall Life. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M.; Cooper, M. Outbound Travel and Quality of Life: The Effect of Airline Price Wars. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heck, H.L.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M. Leisure Sickness: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. Psychol. Top. 2007, 16, 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-C.; Petrick, J.F. Health and Wellness Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bloom, J.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Sonnentag, S.; Taris, T.; de Weerth, C.; Kompier, M.A.J. How Does a Vacation from Work Affect Employee Health and Well-Being? Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1606–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Lazarevski, K.; Yanamandram, V. Quality of Life and Tourism: A Conceptual Framework and Novel Segmentation Base. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Richards, G. Vacations and the Quality of Life: Patterns and Structures. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, T.E. Health Promoting Effects of Friends and Family on Health Outcomes in Older Adults. Am. J. Health Promot. 2000, 14, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery, Well-Being, and Performance-Related Outcomes: The Role of Workload and Vacation Experiences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Durko, A.M.; Petrick, J.F. Family and Relationship Benefits of Travel Experiences: A Literature Review. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. (Lina) Quality of Life (QOL) and Well-Being Research in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.; Choi, S. Family Vacation Activities and Family Cohesion. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, S. WHO Needs a Holiday? Evaluating Social Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 667–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Meng, F. Chinese Tourists’ Sense of Safety: Perceptions of Expected and Experienced Destination Safety. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1886–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilks, J. Current Issues in Tourist Health, Safety and Security. In Tourism in Turbulent Times; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 3–18. ISBN 978-0-08-044666-0. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, P. Stealth Risks and Catastrophic Risks: On Risk Perception and Crisis Recovery Strategies. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 23, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L.; Moen, B.E.; Rundmo, T. Explaining Risk Perception. An Evaluation of the Psychometric Paradigm in Risk Perception Research. Rotunde 2004, 84, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Chiu, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Safety or Travel: Which Is More Important? The Impact of Disaster Events on Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination Image as a Mediator between Perceived Risks and Revisit Intention: A Case of Post-Disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and Implications for Advancing and Resetting Industry and Research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, F. COVID-19: Potential Effects on Chinese Citizens’ Lifestyle and Travel. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, R. Reducing the Health Risks Associated with Travel. Tour. Econ. 2000, 6, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.C. Tourism Crises: Causes, Consequences and Management; Elsevier: Burlington, VT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ETC. Monitoring Sentiment for Domestic and Intra-European Travel. Available online: https://etc-corporate.org/reports/monitoring-sentiment-for-domestic-and-intra-european-travel-wave-9/ (accessed on 17 November 2021).

- Mawby, R.I. Tourists’ Perceptions of Security: The Risk—Fear Paradox. Tour. Econ. 2000, 6, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A. Travel Risks vs. Tourist Decision Making: A Tourist Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Syst. 2015, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xia, E.; He, T. Influence of Traveller Risk Perception on the Willingness to Travel in a Major Epidemic. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazneen, S.; Hong, X.; Ud Din, N. COVID-19 Crises and Tourist Travel Risk Perceptions. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzanegan, M.R.; Gholipour, H.F.; Feizi, M.; Nunkoo, R.; Andargoli, A.E. International Tourism and Outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID-19): A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Lopes, H.; Remoaldo, P.C.; Ribeiro, V.; Martín-Vide, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Tourist Risk Perceptions—The Case Study of Porto. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.M.; Sharifpour, M.; Ritchie, B.W.; Watson, B. Travelers’ Health Risk Perceptions and Protective Behavior: A Psychological Approach. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angguni, F.; Lenggogeni, S. The Impact of Travel Risk Perception in COVID 19 and Travel Anxiety toward Travel In-Tention on Deomestic Tourist in Indonesia. J. Ilmiah MEA (Manaj. Ekon. Akunt.) 2021, 5, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeloye, D.; Brown, L. Terrorism and Domestic Tourist Risk Perceptions. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2018, 16, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the Perceived Risk from COVID-19 on Intention to Travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D. The Effects of Terrorism on the Travel and Tourism Industry. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2014, 2, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) Risk Perception on Behavioural Intention towards ‘Untact’ Tourism in South Korea during the First Wave of the Pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.-K.; Ding, C.G.; Lee, H.-Y. Post-SARS Tourist Arrival Recovery Patterns: An Analysis Based on a Catastrophe Theory. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepp, A.; Gibson, H. Tourist Roles, Perceived Risk and International Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 606–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel Anxiety and Intentions to Travel Internationally: Implications of Travel Risk Perception. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusterschitz, C.; Schütz, H.; Wiedemann, P.M. Looking for a Safe Haven after Fancy Thrills: A Psychometric Analysis of Risk Perception in Alpine Tourist Destinations. J. Risk Res. 2010, 13, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel Risk Perception and Travel Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic 2020: A Case Study of the DACH Region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A.; Kaplanidou, K. Examining the Influence of Past Travel Experience, General Web Searching Behaviour and Risk Perception on Future Travel Intentions. Int. J. Saf. Secur. Tour. 2011, 1, 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, A.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Kaplanidou, K.; Zhan, F. Destination Risk Perceptions among U.S. Residents for London as the Host City of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Bai, B.; Hu, C.; Wu, C.-M.E. Affect, Travel Motivation, and Travel Intention: A Senior Market. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, D.; Işık, C.; Dogru, T.; Zhang, L. Solo Female Travel Risks, Anxiety and Travel Intentions: Examining the Moderating Role of Online Psychological-Social Support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; Vassos, V. Perceived Risk and Risk Reduction in Holiday Purchases: A Cross-Cultural and Gender Analysis. J. Euromarket. 1998, 6, 47–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, L.K.; Ting, C.; Alananzeh, O.A.; Hua, K. Perceptions of Risk and Outbound Tourism Travel Intentions among Young Working Malaysians. Dirasat. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2019, 46, 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.X.; Gibson, H.J.; Zhang, J.J. Perceptions of Risk and Travel Intentions: The Case of China and the Beijing Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 43–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNWTO. Supporting Jobs and Economies through Travel and Tourism. A Call for Action to Mitigate Socio-Economic Impact of COVID-19 and Accelerate Recovery. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/supporting-jobs-and-economies-through-travel-and-tourism (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Enger, W.; Saxon, S.; Suo, P.; Yu, J. The Way Back: What the World Can Learn from China’s Travel Restart after COVID-19. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-transport-and-logistics/ourinsights/the-way-back-what-the-world-can-learn-from-chinas-travel-restart-after-covid-19 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Wachyuni, S.S.; Kusumaningrum, D.A. The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic: How Are the Future Tourist Behavior? J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2020, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Cheon, S.H.; Choi, K.; Joh, C.-H.; Lee, H.-J. Exposure to Fear: Changes in Travel Behavior during MERS Outbreak in Seoul. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 2888–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyanto, I.; Wiblishauser, M.; Pennington-Gray, L.; Schroeder, A. The Dynamics of Travel Avoidance: The Case of Ebola in the U.S. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. The Effect of COVID-19 and Subsequent Social Distancing on Travel Behavior. Transp. Res. Interdisc. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.K.; Chan, H.H.H.; Yi, Y.Y.; Tang, A.; Wei, W.I.; Wong, S.Y.S. Community Responses during Early Phase of COVID-19 Epidemic, Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotle, S.; Murray-Tuite, P.; Singh, K. Influenza Risk Perception and Travel-Related Health Protection Behavior in the US: Insights for the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Outbreak. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 5, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.; Ivanov, I.K.; Ivanov, S. Travel Behaviour after the Pandemic: The Case of Bulgaria. Anatolia 2021, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgiantakis, M.; Apostolakis, A.; Dimou, I. COVID-19 and Holiday Intentions: The Case of Crete, Greece. Anatolia 2021, 32, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratić, M.; Radivojević, A.; Stojiljković, N.; Simović, O.; Juvan, E.; Lesjak, M.; Podovšovnik, E. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Tourists’ COVID-19 Risk Perception and Vacation Behavior Shift. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zámková, M.; Prokop, M. Comparison of Consumer Behavior of Slovaks and Czechs in the Market of Organic Products by Using Correspondence Analysis. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2014, 62, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hebák, P.; Hustopecký, J.; Pecáková, I.; Průša, M.; Řezánková, H.; Svobodová, A.; Vlach, P. Multidimensional Statistical Methods 3; Informatorium: Prague, Czech Republic, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, J.L. Curso de Estadística. Available online: https://estadisticaorquestainstrumento.wordpress.com (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Cortina, J.M. What Is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics Notes: Cronbach’s Alpha. BMJ 1997, 314, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, L. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill Higher, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van Griethuijsen, R.A.L.F.; van Eijck, M.W.; Haste, H.; den Brok, P.J.; Skinner, N.C.; Mansour, N.; Savran Gencer, A.; BouJaoude, S. Global Patterns in Students’ Views of Science and Interest in Science. Res. Sci. Educ. 2015, 45, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. Scale Development: Theory and Applications: Theory and Application; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Dias, C.; Muley, D.; Shahin, M. Exploring the Impacts of COVID-19 on Travel Behavior and Mode Preferences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).