Adapting Sanitation Needs to a Latrine Design (and Its Upgradable Models): A Mixed Method Study under Lower Middle-Income Rural Settings

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Brief Background to Rural Sanitation in Zimbabwe

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Description of the Study Area

2.2. Sample Size and Research Instruments

2.3. Study Variables and Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Survey Respondents

3.2. Determinants of BVIP Latrine Ownership among Rural Households

3.3. Perceptions and Practices of Respondents on Household Sanitation

3.3.1. Sanitation Facility at Household

3.3.2. Access to a Household Latrine

3.3.3. Latrine Preferences

3.3.4. Willingness to Pay and Take up Loan for Latrine Construction or Improvements

3.4. Characteristics of Participants in Focus Groups

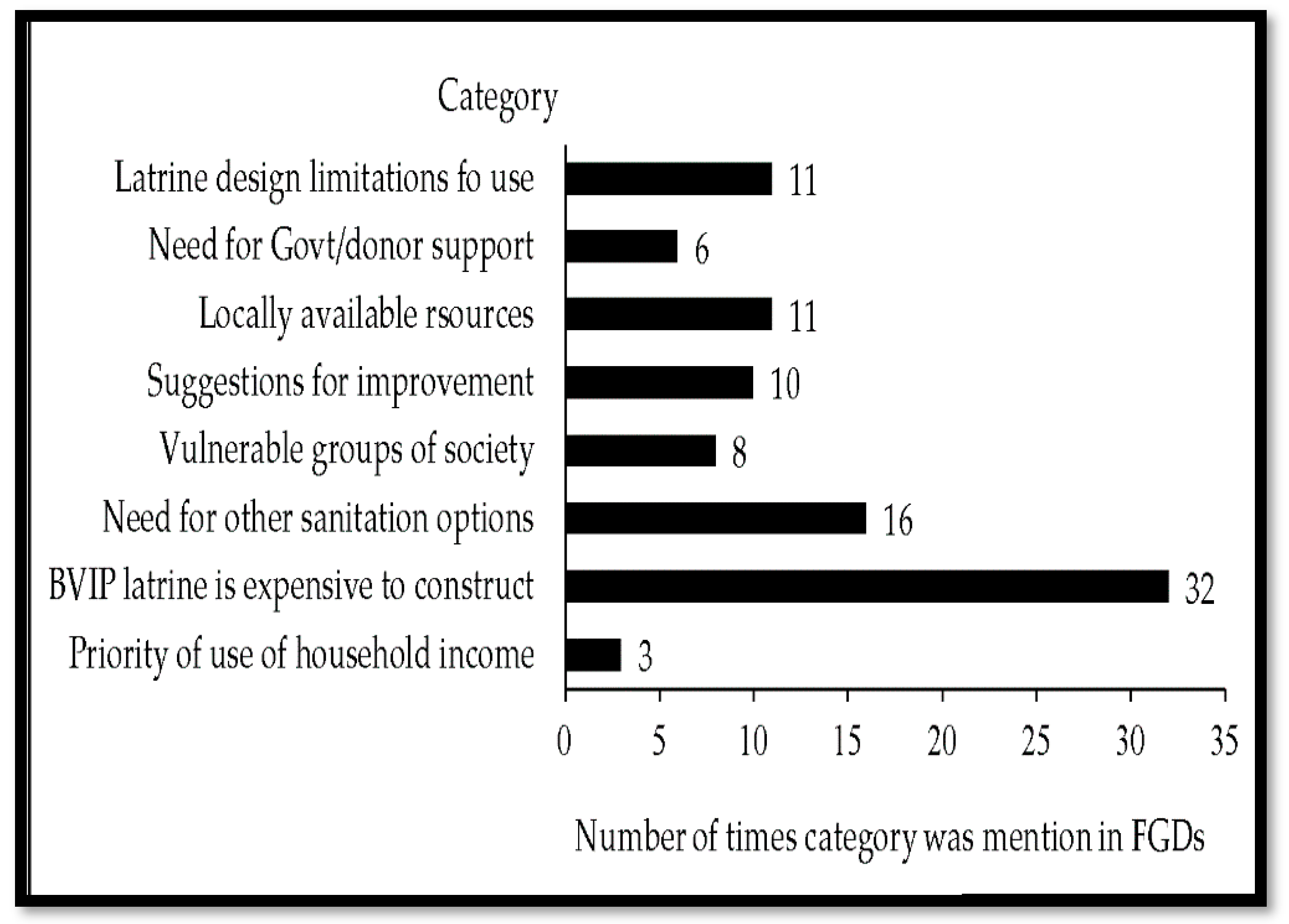

3.5. Shared Household Experiences with BVIP Latrines

3.6. Latrine Adoption Experiences

“A 50 kg bag of cement costs about 12 USD. A standard BVIP latrine needs 6–7 bags of cement. So we need to use 84 USD just to buy cement. What of paying for the builder’s services, buying PVC, vent pipe, fly screen and reinforcement material for the concrete slab?”.

“We have other things that need to be prioritised than building toilets. … little to sell. We need to pay for school fees, food, clothes, and other issues that come first before the latrine. After all, we are hungry and do not have anything in our stomachs to empty into the latrines”

“… Although we can mould bricks, supply sand, concrete stones, water and dig the pits ourselves, we cannot buy cement, iron steel rods and PVC vent pipes to build the recommended BVIP latrine. We receive very little rainfall in our area over a short period. So we cannot build water-based latrines. The result is pit latrines with slabs made of logs and mud, and grass or plastic walls without roofs. Most people end-up using the bush”(Ward 5, Female, 26–45 years of age group).

“In some villages, the elderly get assistance from the village for pit digging, supply of water, concrete stones and river sand for the construction of a BVIP latrine. This help can be extended to free latrine construction. If there are relevant interventions, the elderly are the first to receive assistance including a completed latrine...”.

“The father has the final say in the sale of goats and cattle, and what to use the money for, whether building a latrine or not. Mothers are not empowered to make such decisions in the home. What we can do…”(W 9*, Female, 36–45 years of age group).

“A number of BVIP latrines have collapsed …. I think this is to do with the sandy soils we have in our area. This is observed especially during the rainy season. If we can have other latrine types”

“The pits are filled with water in the rainy season allowing faecal matter to be near the surface of the pit. This results in family members not using the latrine. Also, houseflies can move in and out of the pit freely. This allows diarrhoeal outbreaks.”

3.7. Latrine Use

“… temperature is very high, household members can bath in the latrine to reduce strong odour by reducing temperature. Alternatively, they can add wood ash into the pit”(36–45 years of age group).

“When BVIP latrines collapse or are inaccessible, households can share with neighbours”(Ward 1, Male, 36–45 years of age group).

“In situations where sharing of latrines is not a viable option, household members end up using the bush”(Ward 10, Female, 36–45 years of age group).

“Construction of the BVIP latrine needs trained experienced builders. They charge high fees… In a similar survey which I was involved in, people expressed dissatisfaction with the BVIP latrine for its high cost proposing to resort to the traditional pit latrine with a slab made of wooden logs and mud.”

“The latrine may not be suitable for an extended family where in-laws are staying together. Although very few households still practise this culture, health education is removing such taboos”(26–35 years of age group).

3.8. Suggestions to Improve Rural Sanitation Services

“We also need to try other latrines other than the BVIP latrine since most people cannot afford it. People need latrines but they cannot afford the BVIP latrine encouraged by environmental health technicians and village health workers. This is why we have a lot of traditional pit latrines and others still using the bush. If we have to construct the BVIP latrine only, then we have to get donors coming in”(Ward 10, Male, 36–45 years of age group).

“… There can be options of using other cheaper latrines if they are allowed by our EHTs. Or we are given materials or money by donors to build BVIP latrines and government pay for builders. If that is not done, we end up building other latrine design which we can afford. We can also end up using the bush as a last resort”(Ward 15, Female, 36–45 years of age group).

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. United Nations Sustainable Development Summit, 25–27 September 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Available online: Sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/summit (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Mara, D.; Lane, J.; Scott, B.; Trouba, D. Sanitation and health. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Freeman, M.C.; Garn, J.V.; Sclar, G.D.; Boisson, S.; Medlicott, K.; Alexander, K.T.; Penakalapati, G.; Anderson, D.; Mahtani, A.G.; Grimes, J.E.T.; et al. The impact of sanitation on infectious disease and nutritional status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 928–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund. Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water—2015 Update and MDG Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://files.unicef.org/publications/files/Progress_on_Sanitation_and_Drinking_Water_2015_Update_.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- Satterthwaite, D. Missing the millennium development goal targets for water and sanitation in urban areas. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Development Programme. From MDGs Sustainable Development for All: Lessons Learnt from 15 Years of Practice; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/sustainable-development-goals/from-mdgs-to-sustainable-development-for-all.html (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal Synthesis Report 2018 on Water and Sanitation; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publication_categories/sdg-6-synthesis-report-2018-on-water-and-sanitation/ (accessed on 11 February 2020).

- Martin, N.A.; Hulland, K.R.S.; Dreibelbis, R.; Sultana, F.; Winch, P.J. Sustained adoption of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions: Systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2018, 23, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Legge, H.; Halliday, K.E.; Kepha, S.; Mcharo, C.; Witek-McManus, S.S.; El-Busaidy, H.; Muendo, R.; Safari, T.; Mwandawiro, C.S.; Matendechero, S.H.; et al. Patterns and divers of household sanitation access and sustainability in Kwale County, Kenya. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 6052–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, R.; Tembo, M.; Njera, D.; Kasulo, V.; Malota, M.; Chipeta, W.; Singini, W.; Mchenga, J. Adopters and non-adopters of low-cost household latrines: A study of corbelled pit latrines in 15 districts of Malawi. Sustainability 2016, 8, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simiyu, S. Preference for and characteristics of an appropriate sanitation technology for the slums of Kisumu, Kenya. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2017, 9, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turrén-Cruz, T.; García-Rodríguez, J.A.; Peimbert-García, R.E.; Zavala, M.A.L. An approach incorporating user preferences in the design of sanitation systems and its application in the rural communities of Chiapas, Mexico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Routray, P.; Schmidt, W.-P.; Boisson, S.; Clasen, T.; Jenkins, M.W. Socio-cultural and behavioural factors constraining latrine adoption in rural coastal Odisha: An exploratory qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garn, J.V.; Sclar, G.D.; Freemana, M.C.; Penakalapati, G.; Alexander, K.T.; Brooks, P.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Boisson, S.; Medlicott, K.O.; Clasen, T.F. The impact of sanitation interventions on latrine coverage and latrine use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sinha, A.; Corey, L.; Nagel, C.L.; Schmidt, W.P.; Torondel, B.; Boisson, S.; Routray, P.; Clasen, T.F. Assessing patterns and determinants of latrine use in rural settings: A longitudinal study in Odisha, India. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Zimbabwe. The Zimbabwe National Sanitation and Hygiene Policy Draft; National Action Committee for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2017.

- Robinson, A. VIP Latrines in Zimbabwe: From Local Innovation to Global Sanitation Solution; Field note/WSP, No. 4; Water and Sanitation Programme, African Region: Nairobi, Kenya, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. Zimbabwe’s Rural Sanitation Programme: An Overview of the Main Events; Aquamor: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mukandavire, Z.; Liao, S.; Wang, J.; Gaff, H.; Smith, D.L.; Morris, J.G. Estimating the reproductive numbers for the 2008–2009 cholera outbreaks in Zimbabwe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8767–8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Government of Zimbabwe. The Blair VIP Latrine: A Builder’s Manual for the Upgradeable BVIP Model and a Hand Washing Device; National Action Committee for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Draft: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2011.

- Water and Sanitation Programme. Water Supply, Sanitation in Zimbabwe: Turning Finance into Services for 2015 and Beyond; An AMCOW Country Status Overview; Water and Sanitation Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Zimbabwe. National Water Policy; Ministry of Water Resources Development and Management, Government of Zimbabwe: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2012.

- Morgan, P. The Blair VIP Toilet: Manual for the Upgradeable BVIP Model with Spiral Superstructure and Tubular Vent Pipe; Aquamor: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. Mashonaland Central Province District Population Projections Report; District Population Projections—Zimbabwe; ZimStat: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2020; Available online: https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/publications/Population/population/District-Projections/District-Population-Projection-Report-Mashonaland-central.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee. Annual Update on Rural Livelihoods 2019 Report; Food and Nutrition Council: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee. Annual Update on Rural Livelihoods 2020 Report; Food and Nutrition Council: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. Zimbabwe Poverty Report 2017; ZimStat: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Charan, J.; Biswas, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 35, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berhe, A.A.; Aregay, A.D.; Abreha, A.A.; Aregay, A.B.; Gebretsadik, A.W.; Negash, D.Z.; Gebreegziabher, E.G.; Demoz, K.G.; Fenta, K.A.; Mamo, N.B. Knowledge, attitude, and practices on water, sanitation, and hygiene among rural residents in Tigray region, northern Ethiopia. J. Environ. Public Health 2020, 5460168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund. Core Questions on Drinking Water and Sanitation for Household Surveys; World Health Organization Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2015 Final Report; ZimStat: Harare, Zimbabwe, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nyumba, T.O.; Wilson, K.; Derrick, C.J.; Murkejee, N. The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Method. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothwell, E.; Anderson, R.; Botkin, J.R. Deliberative discussion groups. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dreibelbis, R.; Winch, P.J.; Leontsini, E.; Hulland, K.R.S.; Ram, P.K.; Unicomb, L. The integrated behavioural model for water, sanitation, and hygiene: A systematic review of behavioural models and a framework for designing and evaluating behaviour change interventions in infrastructure-restricted settings. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2012.

- Stata Statistical Software; Release 16; StataCorporation LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2019.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maguire, M.; Delahunt, B. Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. AISH J. 2017, 9, 3351–3364. [Google Scholar]

- NVivo, Version 12; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Melbourne, Australia, 2019.

- Couper, M.P.; Singer, E. The role of numeracy in informed consent for surveys. J. Empir. Res. Ethics 2009, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fischer, B.A. A summary of important documents in the field of research ethics. Schizoph. Bull. 2006, 32, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Länsimies-Antikainen, H.; Laitinen, T.; Rauramaa, R.; Pietilä, A.-M. Evaluation of informed consent in health research: A questionnaire survey. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2010, 24, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keraita, B.; Jensen, P.K.M.; Konradsen, F.; Akple, M.; Rheinländer, T. Accelerating uptake of household latrines in rural communities in the Volta region of Ghana. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2013, 3, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thys, S.; Mwape, K.E.; Lefèvre, P.; Dorny, P.; Marcotty, T.; Phiri, A.M.; Phiri, I.K.; Gabriël, S. Why latrines are not used: Communities’ perceptions and practices regarding latrines in a Taenia solium endemic rural area in eastern Zambia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abebe, T.A.; Tucho, G.T. Open defecation-free slippage and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, M.; Burdett, T.; Heaslip, V. Health and social impacts of open defecation on women: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okullo, J.O.; Moturi, W.N.; Ogendi, G.M. Open defaecation and its effects on the bacteriological quality of drinking water Sources in Isiolo County, Kenya. Environ. Health Insights 2017, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coffey, D.; Spears, D.; Vyas, S. Switching to sanitation: Understanding latrine adoption in a representative panel of rural Indian households. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 188, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Kelsey, A.; Mattson, K.; Cronin, A.A.; Mukerji, S.; Graham, J.P. Determinants of toilet ownership among rural households in six eastern districts of Indonesia. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2018, 8, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busienei, P.J.; Ogendi, G.M.; Mokua, M.A. Latrine structure, design, and conditions, and the practice of open defecation in Lodwar town, Turkana County, Kenya: A quantitative methods research. Environ. Health Insights 2019, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemu, F.; Kumie, A.; Medhin, G.; Gasana, J. The role of psychological factors in predicting latrine ownership and consistent latrine use in rural Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vyas, V.; Spears, D. Sanitation and religion in South Asia: What accounts for differences across countries? J. Dev. Stud. 2018, 54, 2119–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Banze, F.; Guo, J.; Xiaotao, S. Variability and trends of rainfall, precipitation and discharges over Zambezi river basin, southern Africa: Review. Int. J. Hydrog. 2018, 2, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kema, K.; Semali, I.; Mkuwa, S.; Kagonji, I.; Temu, F.; Ilako, F.; Mkuye, M. Factors affecting the utilisation of improved ventilated latrines among communities in Mtwara rural district, Tanzania. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2012, 13, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Njuguna, J. Progress in sanitation among poor households in Kenya: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Connell, K. What Influences Open Defaecation and Latrine Ownership in Rural Households? Findings from a Global View; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Routray, P.; Torondel, B.; Clasen, T.; Schmidt, W.-P. Women’s role in sanitation decision making in rural coastal Odisha, India. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashemi, S. Sanitation sustainability index: A pilot approach to develop a community-based indicator for evaluating sustainability of sanitation systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Categories | Count | % | Pearson χ2-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2-Test Value | p-Value | ||||

| 1. Sex | Female | 587 | 74.3 | 0.022 | 0.881 |

| Male | 203 | 25.7 | |||

| 2. Marital status | Married | 707 | 89.5 | 4.904 | 0.179 |

| Never married | 62 | 7.8 | |||

| Divorced | 7 | 0.9 | |||

| Widowed | 14 | 1.8 | |||

| 3. Age group (years) | 18–25 | 129 | 16.3 | 6.774 | 0.148 |

| 26–35 | 135 | 17.1 | |||

| 36–45 | 238 | 30.1 | |||

| 46–55 | 155 | 19.6 | |||

| Greater than 55 | 133 | 16.8 | |||

| 4. Highest educational level | No formal education | 108 | 13.7 | 10.447 | 0.015 |

| Primary | 505 | 63.9 | |||

| Secondary | 159 | 20.1 | |||

| Tertiary | 18 | 2.3 | |||

| 5. Ethnicity | Korekore | 494 | 62.5 | 5.394 | 0.145 |

| Chikunda | 179 | 22.7 | |||

| Foreign | 15 | 1.9 | |||

| Other | 102 | 12.9 | |||

| 6. Religion | Christianity | 613 | 77.6 | 6.579 | 0.087 |

| Traditional | 97 | 12.3 | |||

| Muslim | 18 | 2.3 | |||

| None | 62 | 7.8 | |||

| 7. Main source of household income | Employed house head | 19 | 2.4 | 17.476 | 0.002 |

| Sale of crops | 564 | 71.4 | |||

| Small-scale business | 123 | 15.6 | |||

| Paid labour | 32 | 4.1 | |||

| Other | 52 | 6.6 | |||

| 8. Approximate household monthly income (USD) | Less than 50 | 626 | 79.2 | 41.317 | <0.001 |

| 50–100 | 98 | 12.4 | |||

| 101–200 | 50 | 6.3 | |||

| Greater than 200 | 16 | 2.0 | |||

| 9. Household size | Less than or equal to 2 | 63 | 8.0 | 5.393 | 0.067 |

| 3–5 | 360 | 45.6 | |||

| Greater than 5 | 367 | 46.5 | |||

| 10. Nature of family | Nucleus | 456 | 57.7 | 0.472 | 0.492 |

| Extended | 334 | 42.3 | |||

| 11. Number of cattle owned | None | 625 | 79.1 | 9.814 | 0.020 |

| Less than or equal to 3 | 62 | 7.8 | |||

| 4–5 | 61 | 7.7 | |||

| Greater than 5 | 42 | 5.3 | |||

| 12. Functional TV set present | Yes | 50 | 6.3 | 16.975 | <0.001 |

| No | 740 | 93.7 | |||

| 13. Brick-built house/ iron sheets-asbestos roof | Yes No | 624 166 | 79.0 21.0 | 20.886 | <0.001 |

| 14. Residence period of household/years | Less than 2 | 48 | 61.0 | 7.957 | 0.047 |

| 2–10 | 233 | 29.5 | |||

| 11–20 | 226 | 28.6 | |||

| Greater than 20 | 283 | 35.8 | |||

| 15. Know any 3 on-site rural sanitation options | Yes | 402 | 50.9 | 24.471 | <0.001 |

| No | 388 | 49.1 | |||

| 16. Share latrine with neighbours | Yes | 170 | 28.5 | 16.779 | <0.001 |

| No | 426 | 71.5 | |||

| 17. Enlisted for social support | Yes | 482 | 61.0 | 4.087 | 0.028 |

| No | 308 | 39.0 | |||

| Level | Contextual Factors | Psychosocial Factors | Technology Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural/Environmental | |||

| Community | |||

| Household | Household size Source of income Level of income Family set up Number of cattle Residency period | Enlisted for social support | |

| Individual | For the responding house head: Sex, marital status, age group For the male house head: Educational level, Ethnicity, religion | Knowledge of rural sanitation options | BVIP latrine is expensive |

| Habitual |

| Predictor Variable | Coeff | Wald Statistic | p-Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of house head (Male) Female | 0.136 | 0.402 | 0.526 | 1.145 | 0.753, 1.742 |

| Marital status (widowed) 3 Categories | 2.424 | 0.489 | |||

| Age group (18–25 years) 4 Categories | 4.277 | 0.37 | |||

| Educational level (none) 3 Categories | 1.133 | 0.769 | |||

| Ethnicity (Korekore) 3 Categories | 4.86 | 0.182 | |||

| Religion (Christianity) 3 Categories | 3.647 | 0.302 | |||

| Source of income (Self/Employed) | |||||

| Sale of garden/field crops | −0.881 | 2.505 | 0.114 | 0.414 | 0.139, 1.234 |

| Small-scale business/trade | −1.003 | 2.986 | 0.084 | 0.367 | 0.118, 1.144 |

| Paid labour | −2.014 | 6.503 | 0.011 | 0.133 | 0.028, 0.628 |

| Other | −0.666 | 1.108 | 0.293 | 0.514 | 0.148, 1.776 |

| Monthly HH income/USD (<50) 51–100 | 0.614 | 5.123 | 0.024 | 1.848 | 1.086, 3.145 |

| 101–200 | 1.203 | 10.032 | 0.002 | 3.329 | 1.582, 7.006 |

| >200 | 1.747 | 6.716 | 0.01 | 5.737 | 1.531, 21.504 |

| Household size (≤2) 2 Categories | 3.773 | 0.152 | |||

| Family setup (Nucleus) Extended | −0.147 | 0.558 | 0.455 | 0.863 | 0.587, 1.270 |

| Number of cattle owned (None) ≤ 3 | 0.226 | 0.509 | 0.476 | 1.253 | 0.674, 2.332 |

| 4–5 | 0.629 | 4.287 | 0.038 | 1.875 | 1.034, 3.400 |

| >5 | 0.122 | 0.098 | 0.754 | 1.129 | 0.527, 2.420 |

| Nature of homestead (Yes) No | −0.786 | 9.287 | 0.002 | 0.455 | 0.275, 0.755 |

| Residence period/years (<2) 2–10 | 0.146 | 0.115 | 0.734 | 1.158 | 0.498, 2.693 |

| 11–20 | 0.239 | 0.275 | 0.6 | 1.271 | 0.520, 3.107 |

| >20 | 1.059 | 5.318 | 0.021 | 2.883 | 1.172, 7.091 |

| Enlisted for social support (No) Yes | −0.365 | 3.038 | 0.081 | 0.694 | 0.460, 1.046 |

| Knowledge of rural sanitation | |||||

| technology options (No) Yes | −0.707 | 13.304 | <0.001 | 0.493 | 0.337, 0.721 |

| BVIP latrine is expensive (No) Yes | −2.437 | 17.624 | <0.001 | 0.087 | 0.028, 0.273 |

| Constant | 0.146 | 0.009 | 0.922 | 1.157 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanda, A.; Ncube, E.J.; Voyi, K. Adapting Sanitation Needs to a Latrine Design (and Its Upgradable Models): A Mixed Method Study under Lower Middle-Income Rural Settings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313444

Kanda A, Ncube EJ, Voyi K. Adapting Sanitation Needs to a Latrine Design (and Its Upgradable Models): A Mixed Method Study under Lower Middle-Income Rural Settings. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313444

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanda, Artwell, Esper Jacobeth Ncube, and Kuku Voyi. 2021. "Adapting Sanitation Needs to a Latrine Design (and Its Upgradable Models): A Mixed Method Study under Lower Middle-Income Rural Settings" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313444

APA StyleKanda, A., Ncube, E. J., & Voyi, K. (2021). Adapting Sanitation Needs to a Latrine Design (and Its Upgradable Models): A Mixed Method Study under Lower Middle-Income Rural Settings. Sustainability, 13(23), 13444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313444