What Should Be Focused on When Digital Transformation Hits Industries? Literature Review of Business Management Adaptability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

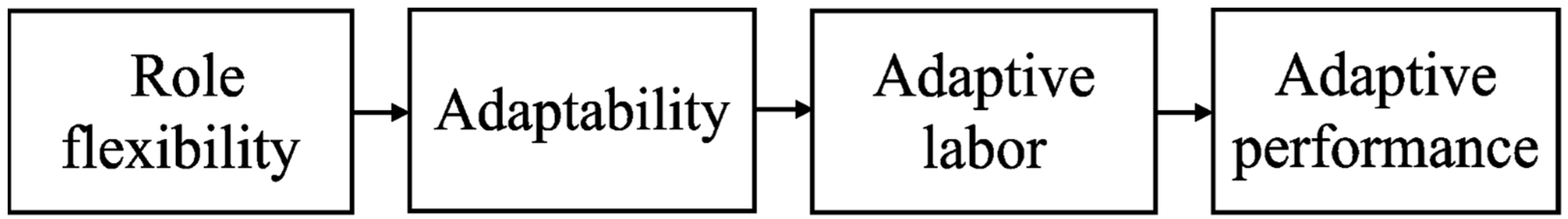

Overview of Adaptability

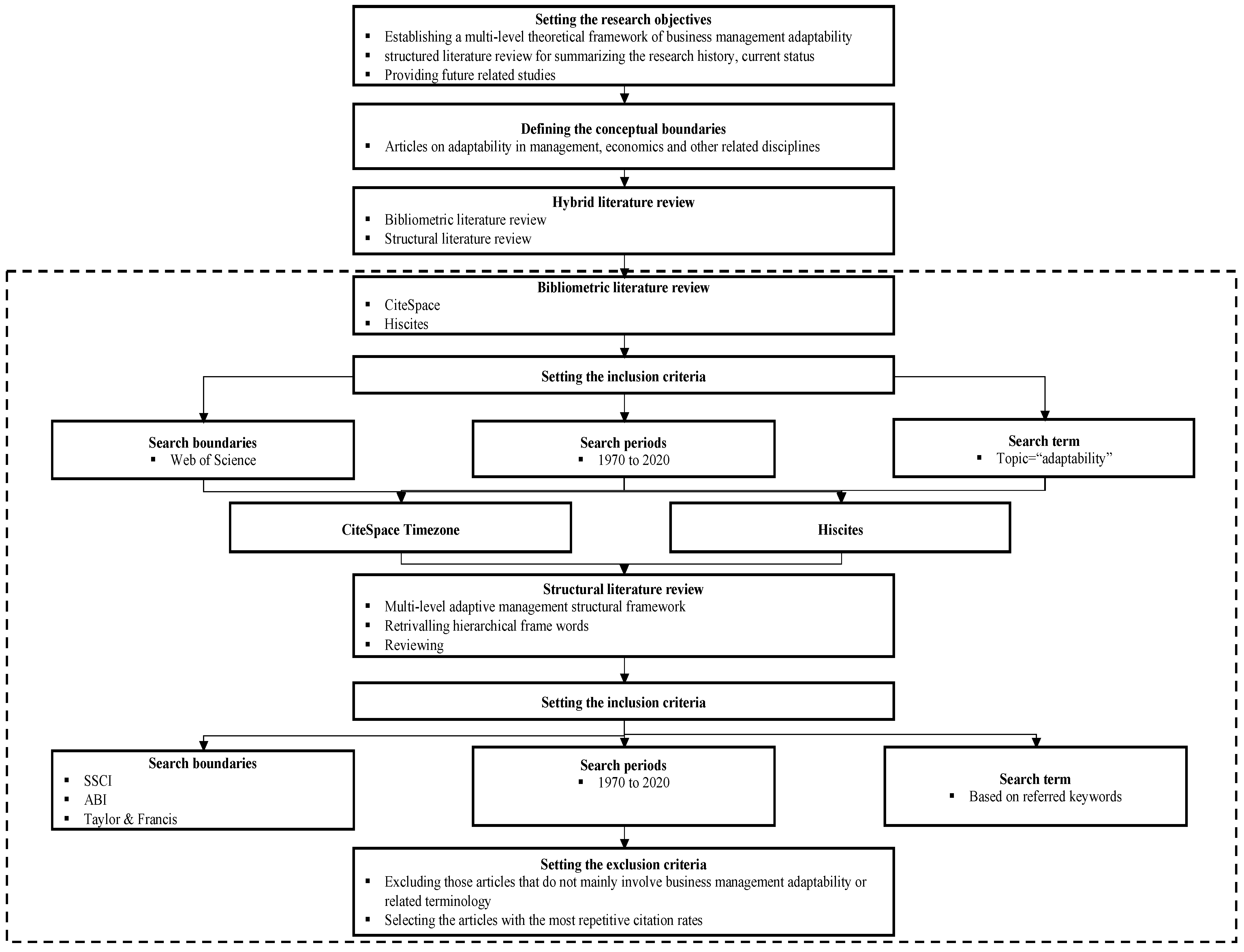

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Boundaries

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2.1. Bibliometric Literature Review

2.2.2. Structural Literature Review

- Double checking with the literature and then conducting a basis for structural business management adaptability;

- Retrieving these basic hierarchical words from multiple databases such as SSCI, ABI, Taylor and Francis;

- Compare, analyze, and integrate the retrieval results to discuss the research status of business management adaptability.

3. Literature Analysis

3.1. General Considerations about Literatures in WOS

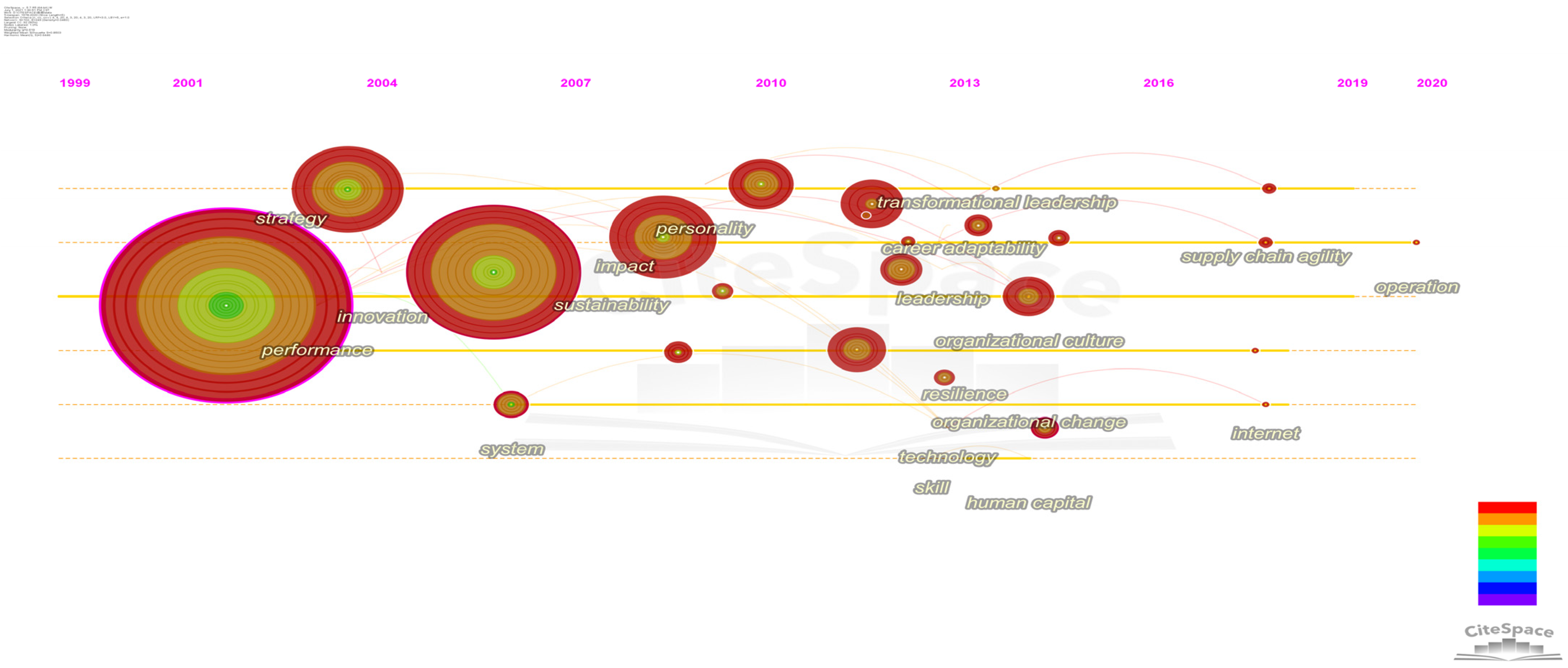

3.2. Context of the Bibliometric Literature Review Research

3.2.1. Analysis by CiteSpace

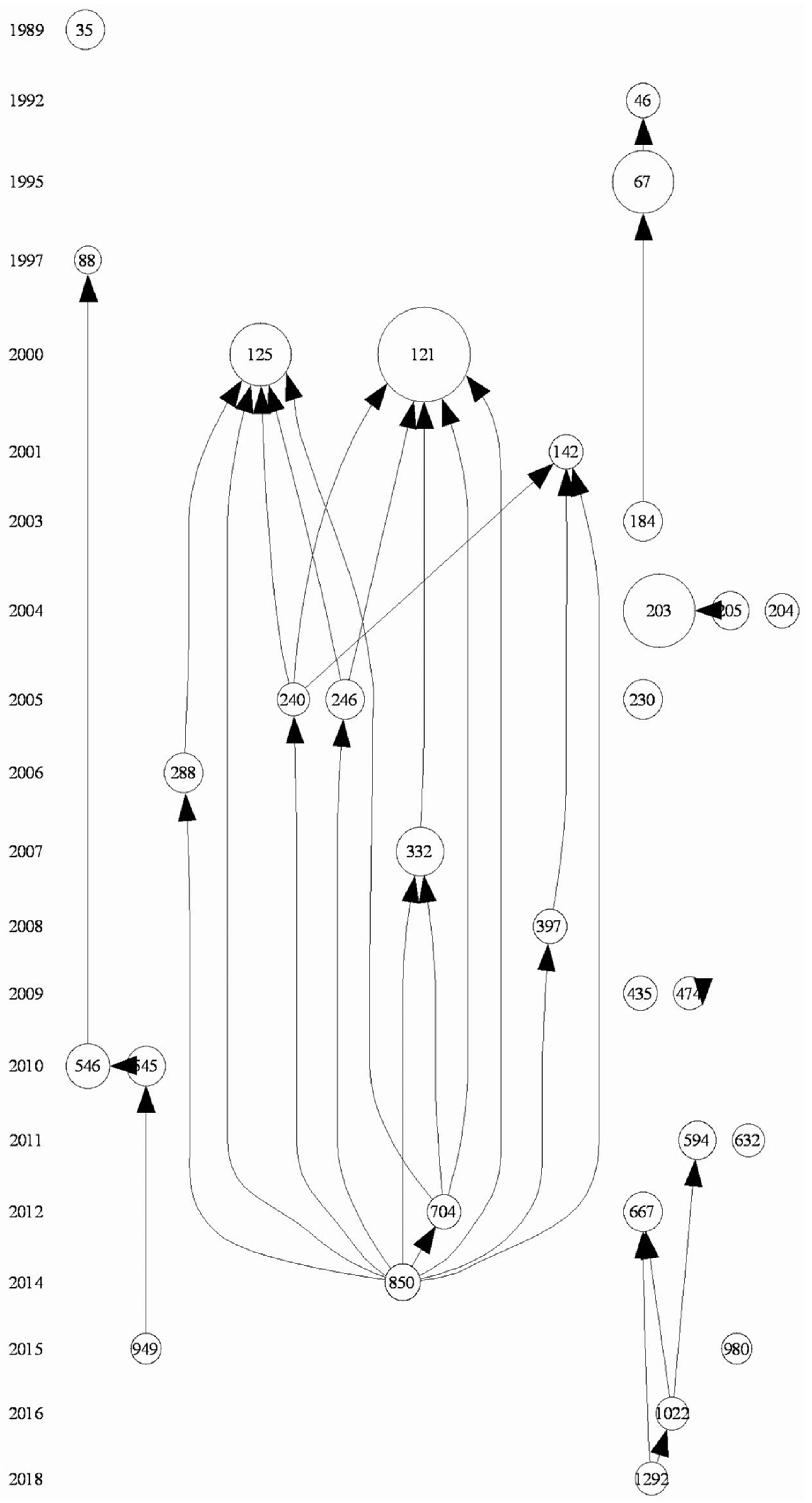

3.2.2. Analysis by HistCite

3.3. Context of the Structural Literature Review Research

3.3.1. Structural Framework of Business Management Adaptability Review

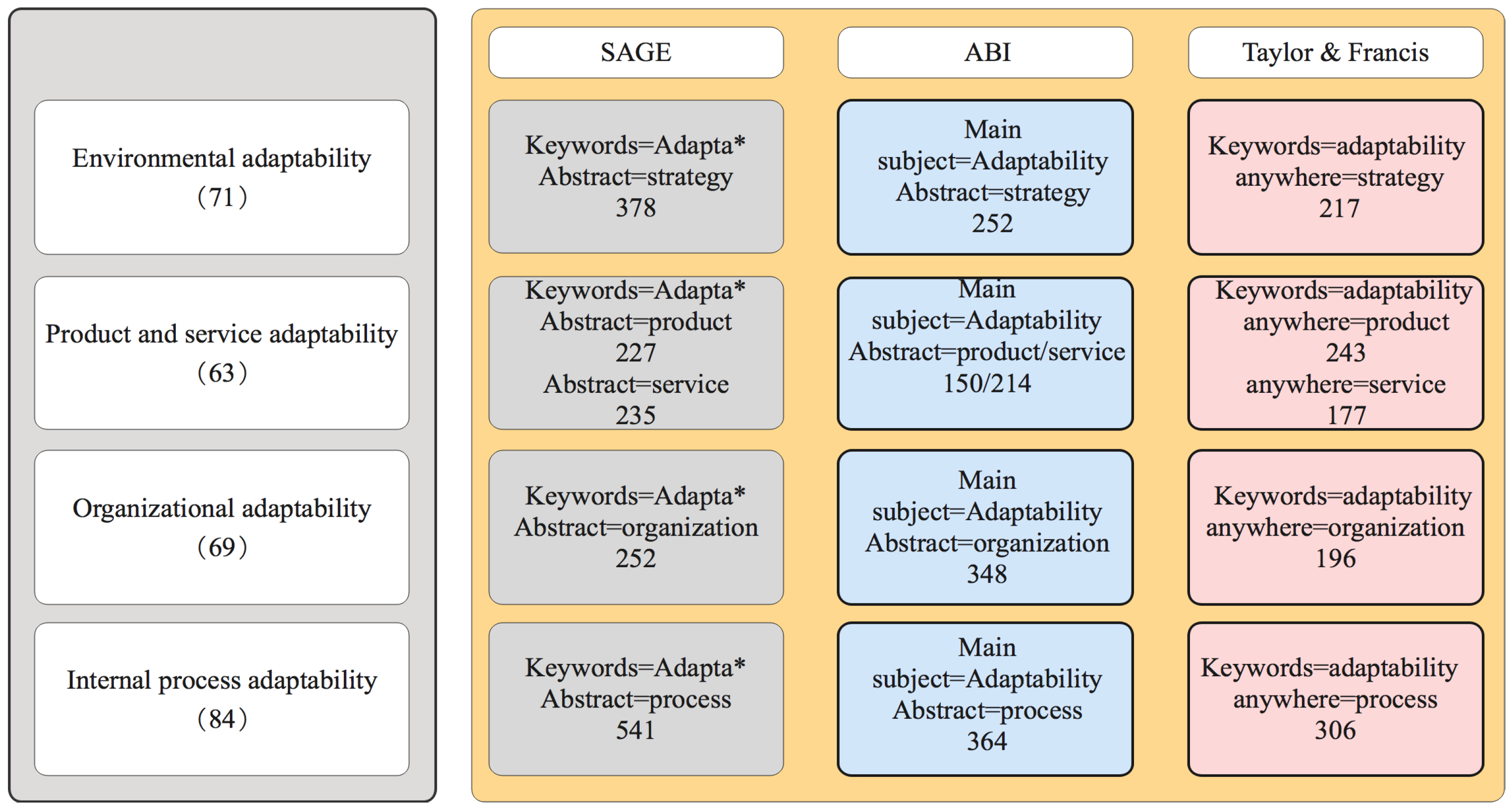

3.3.2. Searching Results of Structural Framework Keywords

4. Structural Review of Business Management Adaptability

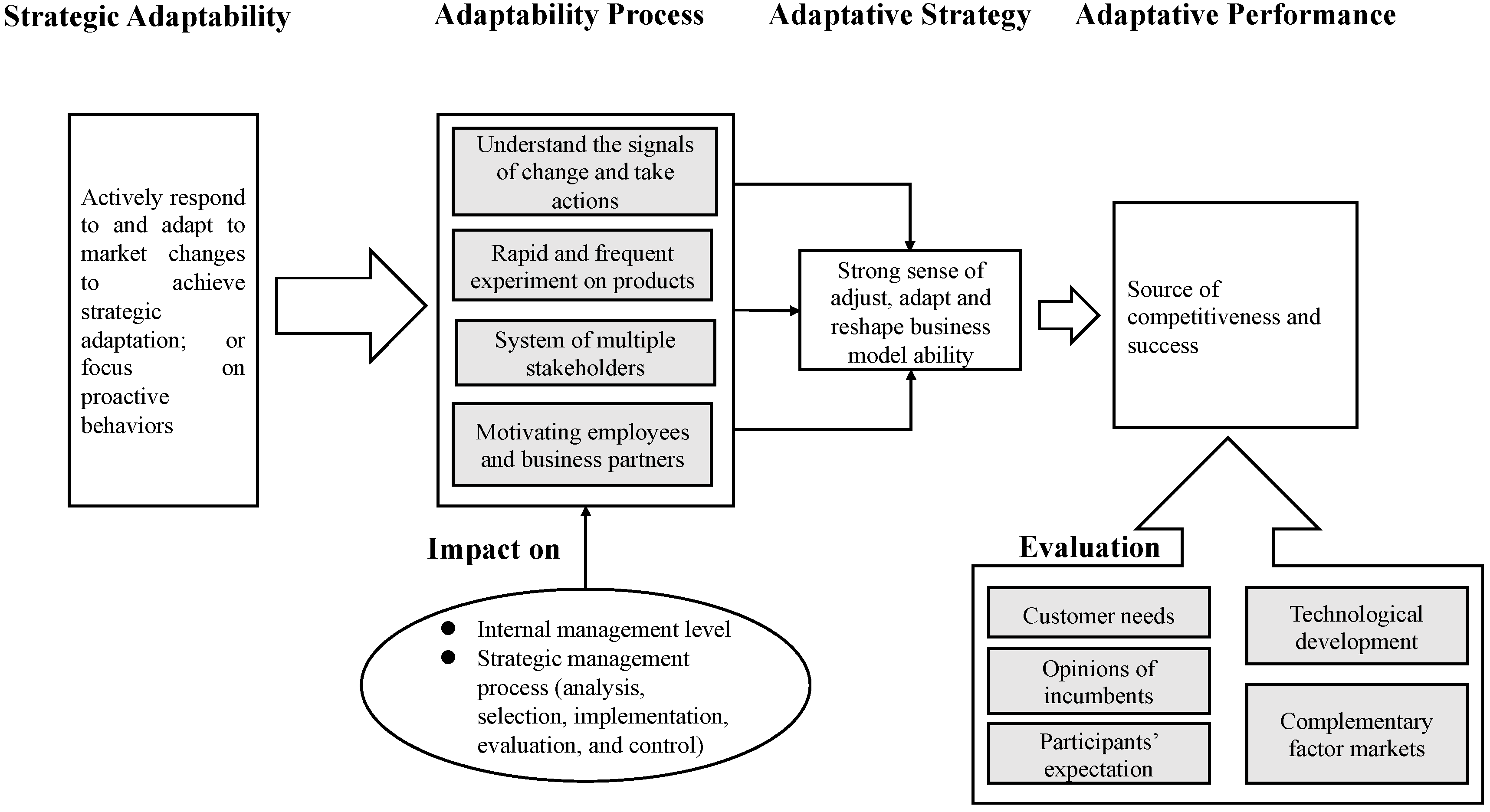

4.1. Strategic Adaptability/Environmental Adaptability

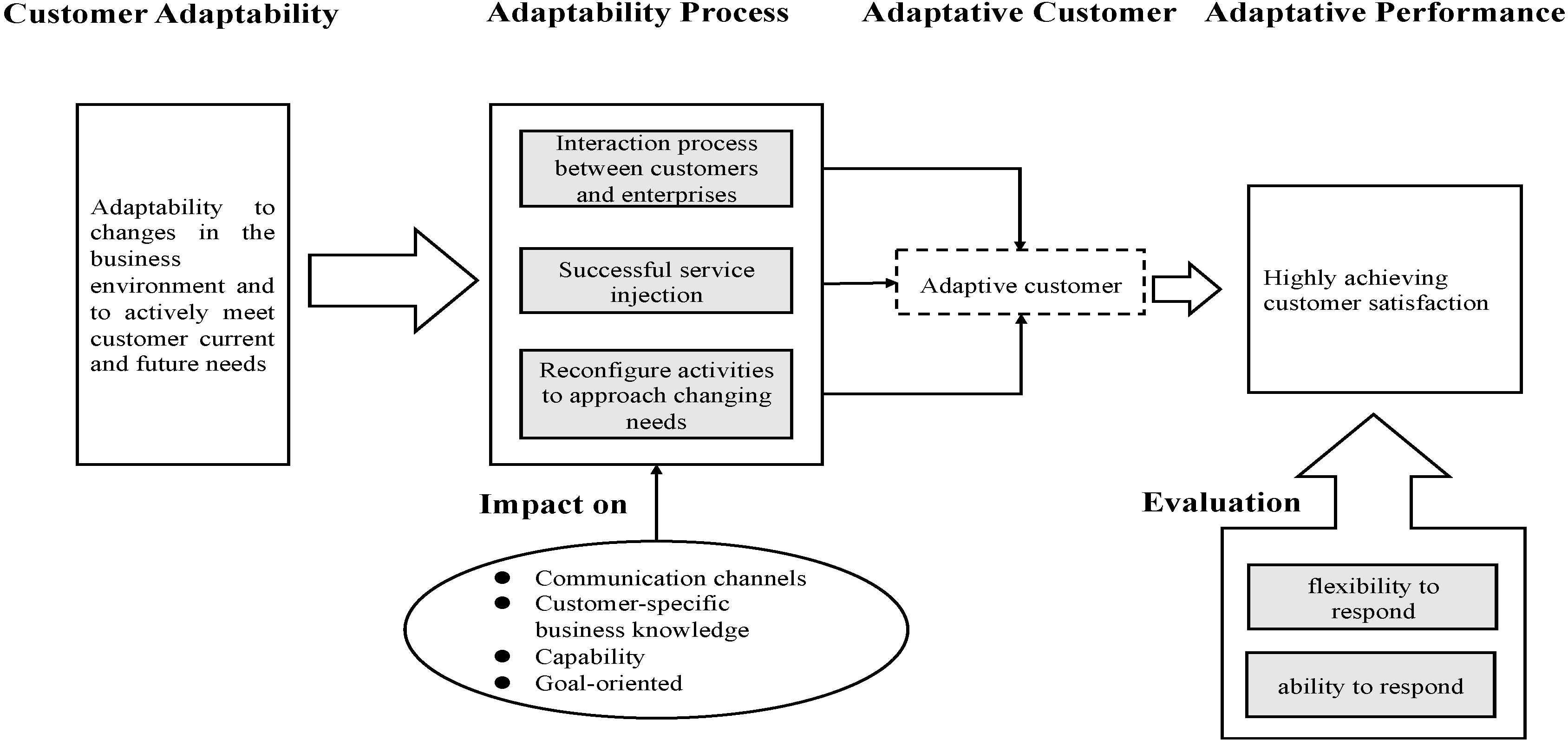

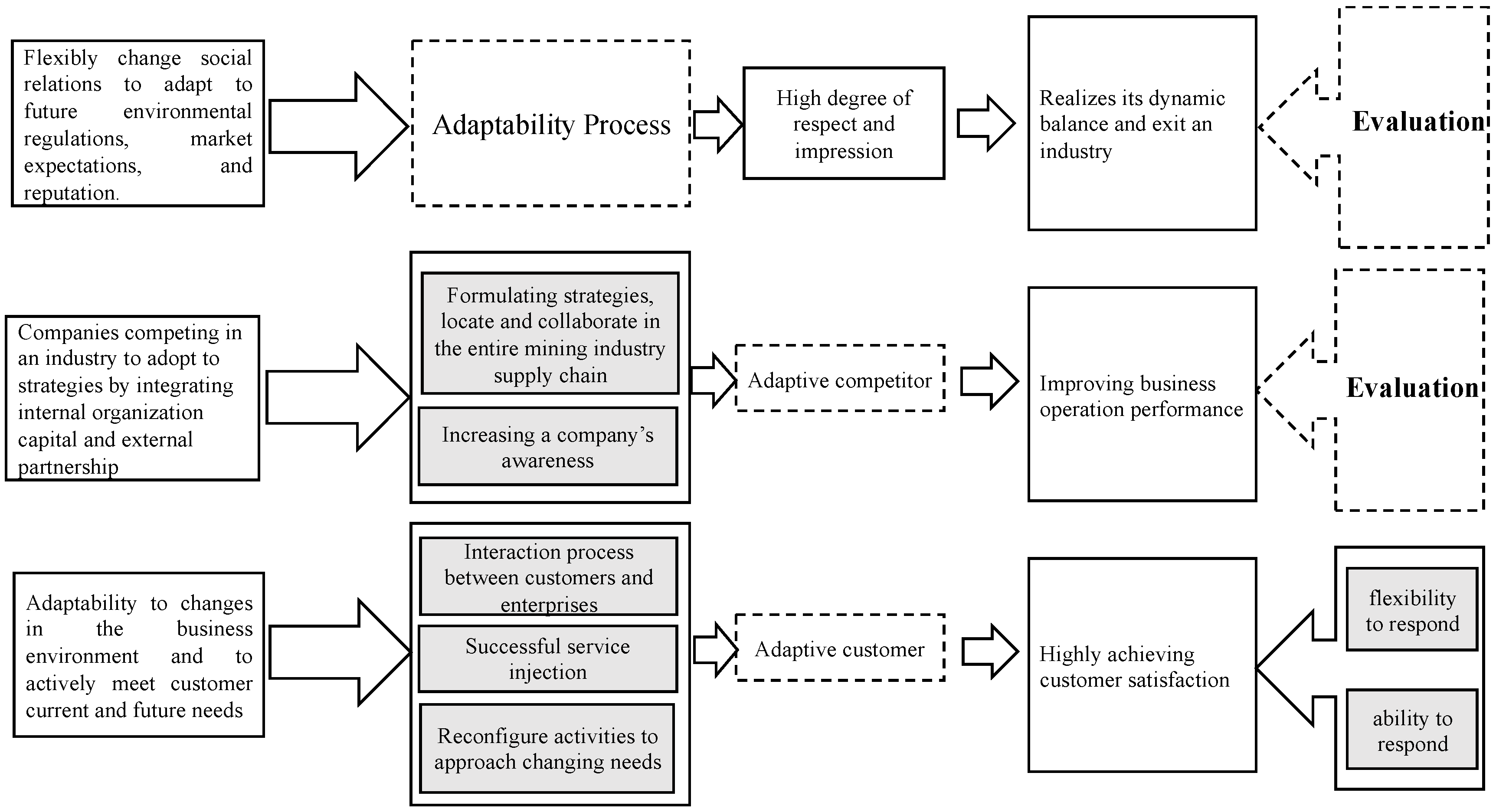

4.1.1. Adaptability to Market/Customer Needs

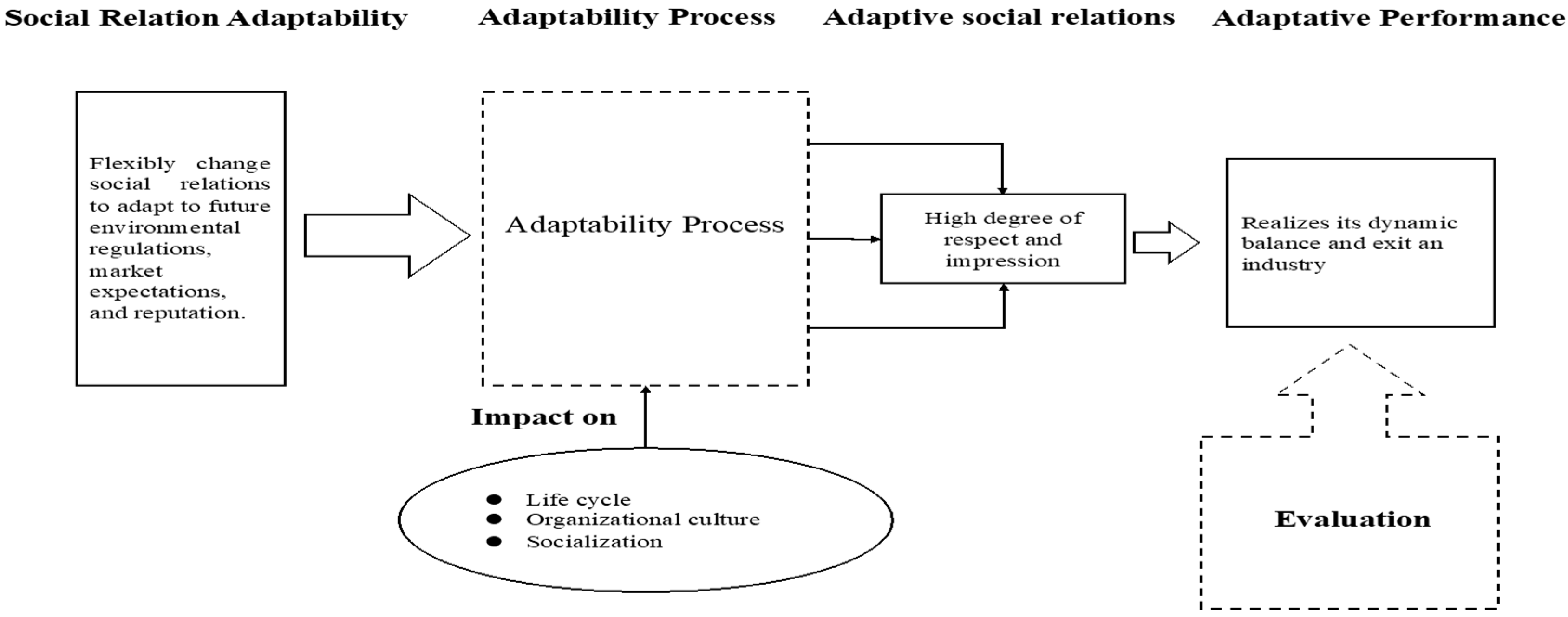

4.1.2. The Adaptability of Social Relations

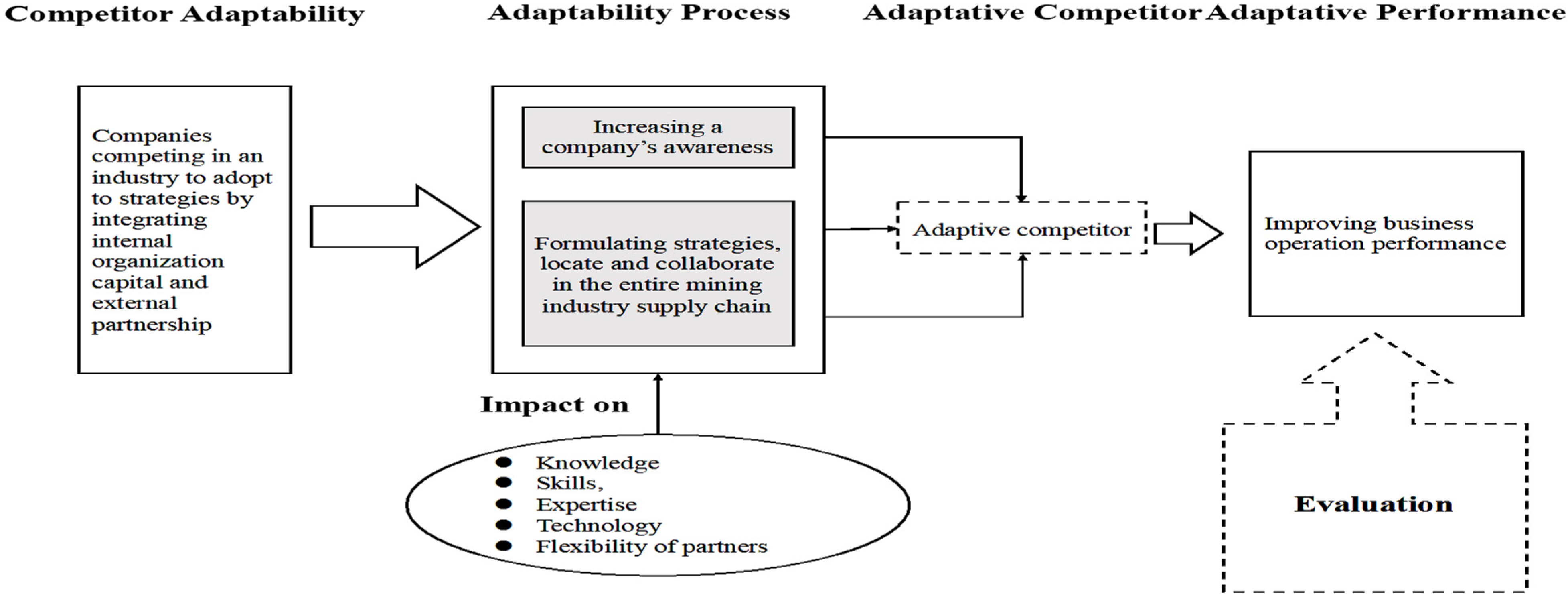

4.1.3. Competitor Adaptability

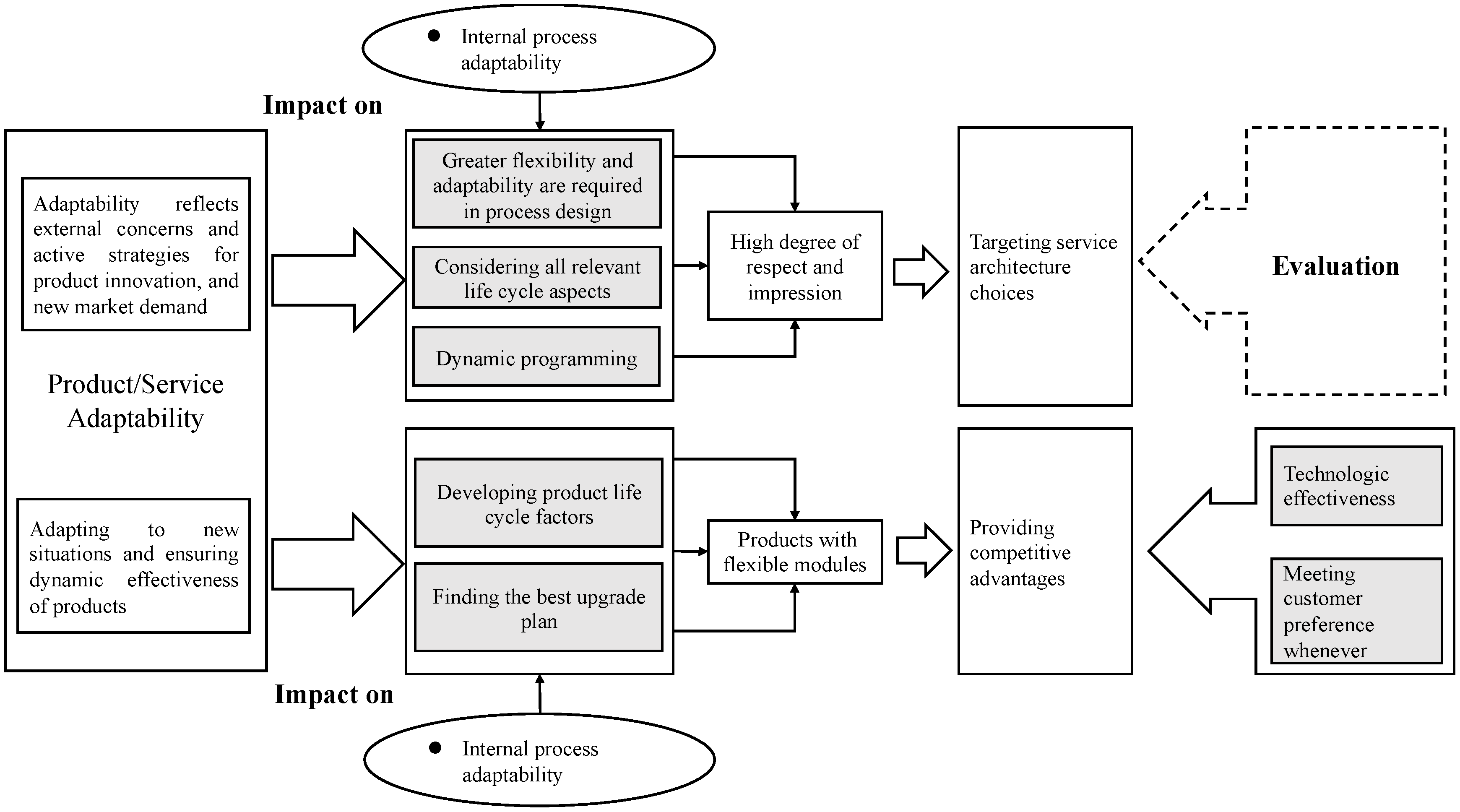

4.2. Product/Service Adaptability

4.3. Organizational Adaptability

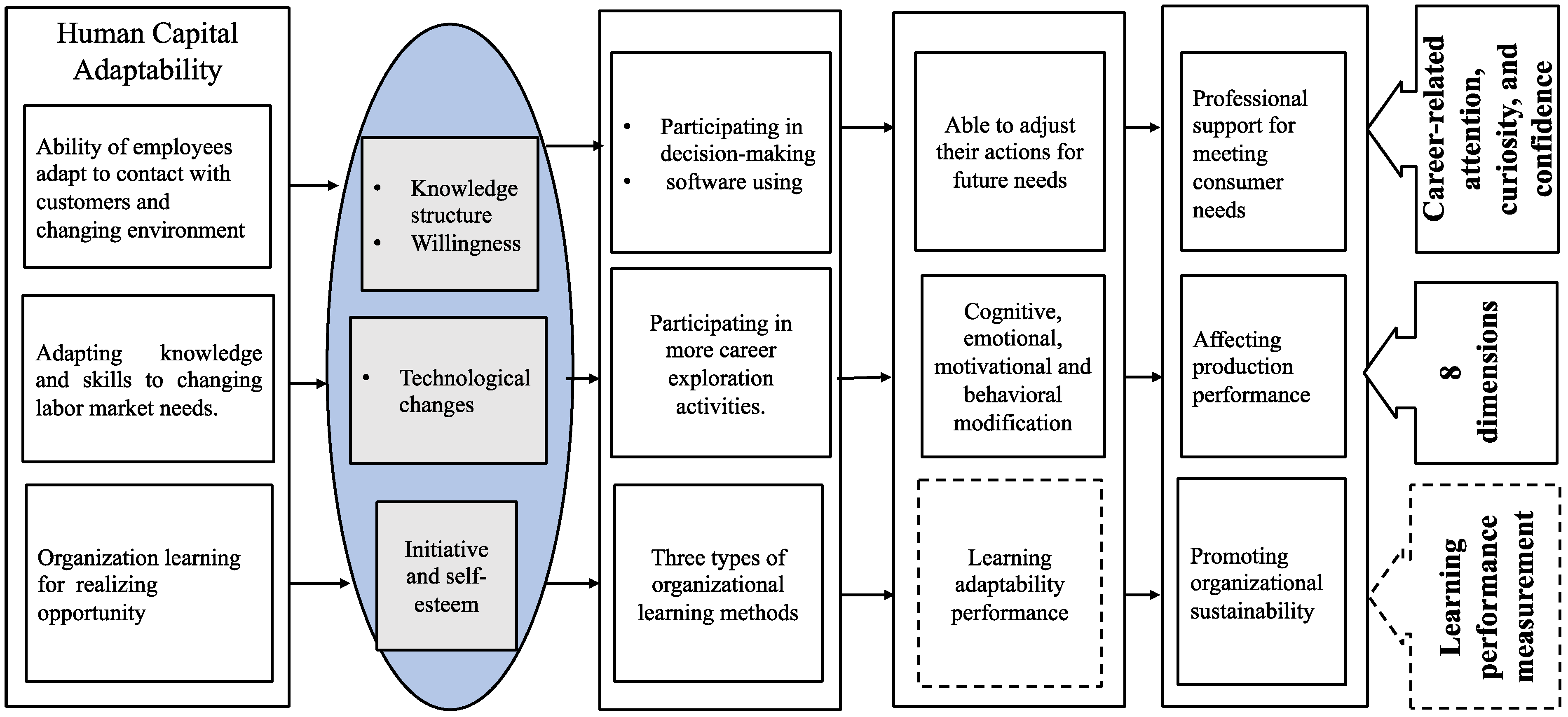

4.3.1. Human Capital Adaptability

4.3.2. Information Capital Adaptability

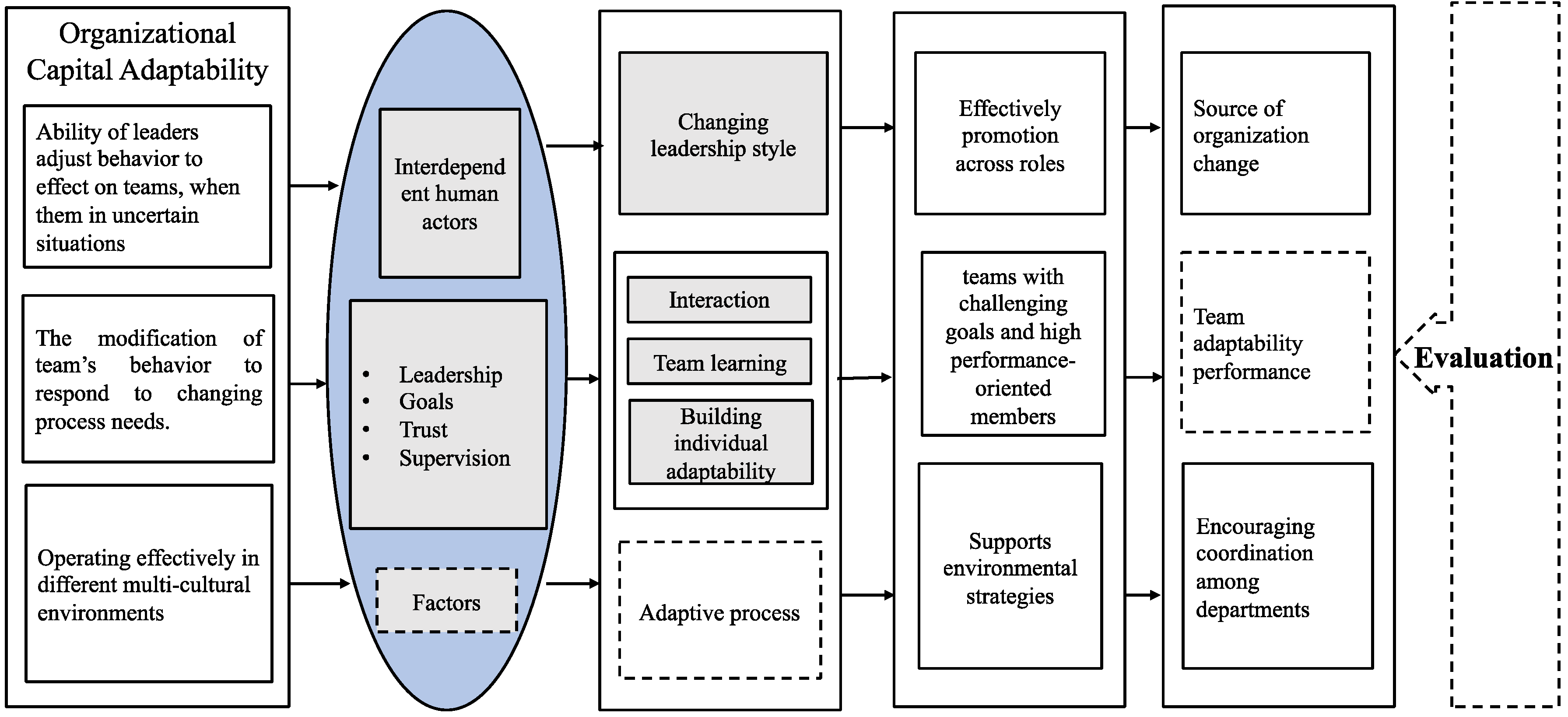

4.3.3. Organizational Capital Adaptability

4.4. Process Management Adaptability

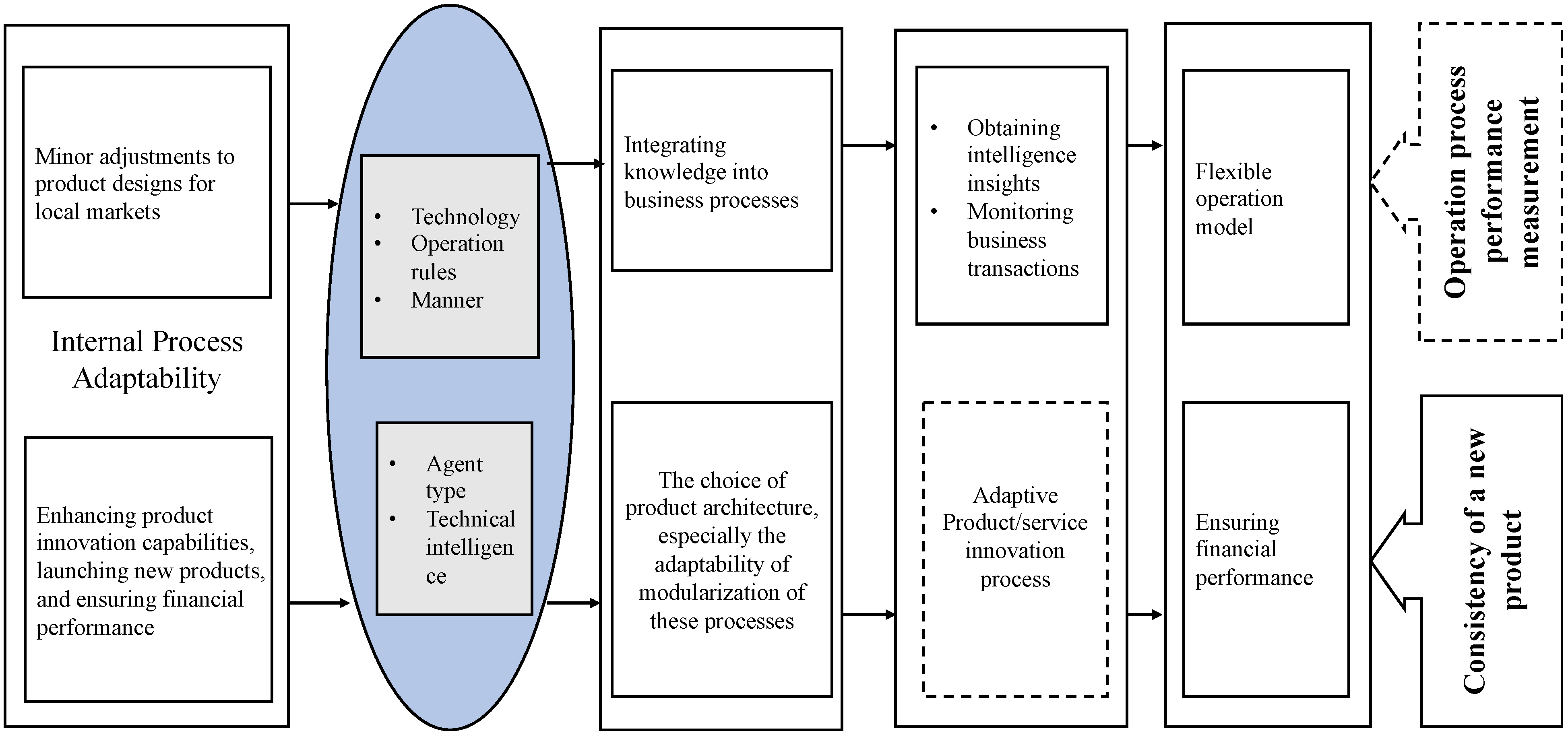

4.4.1. Operation Management Process Adaptability

4.4.2. Product/Service Innovation Process Adaptability

4.5. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| LCS | GCS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 35 | MCKEE DO, 1989, J MARKETING, V53, P21 | 14 | 266 |

| 2. | 46 | GORDON GG, 1992, J MANAGE STUD, V29, P783 | 10 | 256 |

| 3. | 67 | DENISON DR, 1995, ORGAN SCI, V6, P204 | 32 | 703 |

| 4. | 88 | Grabher G, 1997, REG STUD, V31, P533 | 7 | 176 |

| 5. | 121 | Pulakos ED, 2000, J APPL PSYCHOL, V85, P612 | 73 | 565 |

| 6. | 125 | LePine JA, 2000, PERS PSYCHOL, V53, P563 | 33 | 342 |

| 7. | 142 | Kozlowski SWJ, 2001, ORGAN BEHAV HUM DEC, V85, P1 | 10 | 254 |

| 8. | 184 | Carl CF, 2003, ORGAN SCI, V14, P686 | 13 | 135 |

| 9. | 203 | Gibson CB, 2004, ACAD MANAGE J, V47, P209 | 44 | 1788 |

| 10. | 204 | Tuominen M, 2004, J BUS RES, V57, P495 | 10 | 77 |

| 11. | 205 | Birkinshaw J, 2004, MIT SLOAN MANAGE REV, V45, P47 | 12 | 343 |

| 12. | 230 | Ito JK, 2005, HUM RESOURCE MANAGE, V44, P5 | 13 | 110 |

| 13. | 240 | Chen G, 2005, J APPL PSYCHOL, V90, P827 | 9 | 114 |

| 14. | 246 | LePine JA, 2005, J APPL PSYCHOL, V90, P1153 | 13 | 189 |

| 15. | 288 | Burke CS, 2006, J APPL PSYCHOL, V91, P1189 | 14 | 377 |

| 16. | 332 | Griffin MA, 2007, ACAD MANAGE J, V50, P327 | 20 | 946 |

| 17. | 397 | Bell BS, 2008, J APPL PSYCHOL, V93, P296 | 10 | 313 |

| 18. | 435 | Ponomarov SY, 2009, INT J LOGIST MANAG, V20, P124 | 10 | 489 |

| 19. | 474 | Haynie M, 2009, ENTREP THEORY PRACT, V33, P695 | 9 | 92 |

| 20. | 545 | Hassink R, 2010, CAMB J REG ECON SOC, V3, P45 | 13 | 239 |

| 21. | 546 | Pike A, 2010, CAMB J REG ECON SOC, V3, P59 | 17 | 360 |

| 22. | 594 | Christopher M, 2011, INT J PHYS DISTR LOG, V41, P63 | 12 | 267 |

| 23. | 632 | Reeves M, 2011, HARVARD BUS REV, V89, P134 | 9 | 60 |

| 24. | 667 | Whitten GD, 2012, INT J OPER PROD MAN, V32, P28 | 13 | 95 |

| 25. | 704 | Shoss MK, 2012, J ORGAN BEHAV, V33, P910 | 10 | 51 |

| 26. | 850 | Baard SK, 2014, J MANAGE, V40, P48 | 11 | 124 |

| 27. | 949 | Martin R, 2015, J ECON GEOGR, V15, P1 | 8 | 342 |

| 28. | 980 | Schoenherr T, 2015, DECISION SCI, V46, P901 | 8 | 48 |

| 29. | 1022 | Dubey R, 2016, INT J LOGIST-RES APP, V19, P62 | 9 | 97 |

| 30. | 1292 | Dubey R, 2018, INT J OPER PROD MAN, V38, P129 | 9 | 93 |

References

- Christopher, M.; Lee, H. Mitigating supply chain risk through improved confidence. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2004, 34, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reeves, S.; Zwarenstein, M.; Goldman, J.; Barr, H.; Freeth, D.; Koppel, I.; Hammick, M. The effectiveness of interprofessional education: Key findings from a new systematic review. J. Interprof. Care 2010, 24, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, C.G.; Williams, T.D.; Lawler, E.E., III. The Agility Factor: Building Adaptable Organizations for Superior Performance; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, D.M.; Khurana, R. A framework to study vendors’ contribution in a client vendor relationship in information technology service outsourcing in India. Benchmarking Int. J. 2016, 23, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Baucus, D.A. Organizational adaptation to performance downturns: An interpretation-based perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1987, 12, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.P. Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Management research after modernism. Br. J. Manag. 2001, 12, S61–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognini, R.; Corradini, F.; Gnesi, S.; Polini, A.; Re, B. Research challenges in business process adaptability. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, Gyeongju, Korea, 24–28 March 2014; pp. 1049–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Schoenherr, T.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, S. Intellectual capital, supply chain learning, and adaptability: A comparative investigation in China and the United States. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ployhart, R.E.; Bliese, P.D. Individual adaptability (I-ADAPT) theory: Conceptualizing the antecedents, consequences, and measurement of individual differences in adaptability. In Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance within Complex Environments; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1016/S1479-3601(05)06001-7/full/html (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Van Der Aalst, W.M.; La Rosa, M.; Santoro, F.M. Don’t forget to improve the process! Bus. Process Manag. 2016, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C.S. A systematic review of the career adaptability literature and future outlook. J. Career Assess. 2018, 26, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, J.H.; Pinkow, F. Leadership for organisational adaptability: How enabling leaders create adaptive space. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xue, D.; Gu, P. Design for product adaptability. Concurr. Eng. 2008, 16, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar]

- LePine, J.A. Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J.M.; Kelly, P.J.; Nardari, F. Do market efficiency measures yield correct inferences? A comparison of developed and emerging markets. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 3225–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Arad, S.; Donovan, M.A.; Plamondon, K.E. Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stormi, K.T.; Laine, T.; Korhonen, T. Agile performance measurement system development: An answer to the need for adaptability? J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2019, 15, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitbasioglu, O.M. Drivers of management accounting adaptability: The agility lens. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2017, 13, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorndee, K.; Siengthai, S.; Swierczek, F.W. Closing cultural distance: The cultural adaptability in Chinese-related firms in Thailand. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2017, 11, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzold, N.; Landinez, L.; Baaken, T. Disruptive innovation from a process view: A systematic literature review. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2019, 28, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, J.M.; Kwak, C.; Cho, Y.; Kim, C.O. Adaptive product tracking in RFID-enabled large-scale supply chain. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haasnoot, M.; Warren, A.; Kwakkel, J.H. Dynamic adaptive policy pathways (DAPP). In Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Polese, F.; Mele, C.; Gummesson, E. Value co-creation as a complex adaptive process. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 926–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, M.T.; Kennedy, D.M.; Sommer, S.A. Team adaptation: A fifteen-year synthesis (1998–2013) and framework for how this literature needs to “adapt” going forward. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 652–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Dorsey, D.W.; White, S.S. Adaptability in the workplace: Selecting an adaptive workforce. In Understanding Adaptability: A Prerequisite for Effective Performance within Complex Environments; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1016/S1479-3601(05)06002-9/full/html?utm_source=TrendMD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=Advances_in_Human_Performance_and_Cognitive_Engineering_Research_TrendMD_0 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Almahamid, S.; McAdams, A.C.; Kalaldeh, T. The Relationships among Organizational Knowledge Sharing Practices, Employees’ Learning Commitments, Employees’ Adaptability, and Employees’ Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Investigation of the Listed Manufacturing Companies in Jordan. Interdiscip. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 5, 327–357. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.R.; Jackson, S.E. Managing work role performance: Challenges for twenty-first century organizations and their employees. In The Changing Nature of Performance: Implications for Staffing, Motivation and Development; Ilgen, D.R., Pulakos, D.P., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 325–365. [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh, B.; Neal, A. Technology and performance. In The Changing Nature of Work Performance: Implications for Staffing, Motivation, and Development; Ilgen, D., Pukalos, E., Eds.; Jossey Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers, P.A.; Coleman, S.D. Adaptation of the older worker to occupational challenges. Work 2004, 22, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sherehiy, B.; Karwowski, W.; Layer, J.K. A review of enterprise agility: Concepts, frameworks, and attributes. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2007, 37, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E.J.; Savickas, M.L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-USA Form: Psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.R. Personality traits and intrapreneurship: The mediating effect of career adaptability. Career Dev. Int. 2018, 23, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, Y.; Kaandorp, M.; Elfring, T. Toward a dynamic process model of entrepreneurial networking under uncertainty. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maltou, R.; Bahta, Y.T. Factors influencing the resilience of smallholder livestock farmers to agricultural drought in South Africa: Implication for adaptive capabilities. Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2019, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.R.; Winter, S.G. The Schumpeterian tradeoff revisited. Am. Econ. Rev. 1982, 72, 114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1963; Volume 2, pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. Organizational configurations: Cohesion, change, and prediction. Hum. Relat. 1990, 43, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersick, C.J. Revolutionary change theories: A multilevel exploration of the punctuated equilibrium paradigm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, E.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational transformation as punctuated equilibrium: An empirical test. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1141–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, D.A.; Norton, W.E. The adaptome: Advancing the science of intervention adaptation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, S124–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levy, D. Chaos theory and strategy: Theory, application, and managerial implications. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, R.; Combs, A. Chaos Theory in Psychology and the Life Sciences; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2014; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98575-000 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Aphane, M.; de Beer, H.; Kruger, L. Executive and Management Summaries. 2016. Available online: https://sahris.sahra.org.za/sites/default/files/additionaldocs/SAS%20SLR%20Siyanda%20Section%20A%20Summary%20and%20Background%2016092016.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Mason, I. (Ed.) Triadic Exchanges: Studies in Dialogue Interpreting; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/books/mono/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9781315759982&type=googlepdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Stacey, R. Tools and Techniques of Leadership and Management: Meeting the Challenge of Complexity; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/search?kw=Triadic+Exchanges.+Studies+in+Dialogue+Interpreting (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Hung, S.C.; Tu, M.F. Is small actually big? The chaos of technological change. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houry, S.A. Chaos and organizational emergence: Towards short term predictive modeling to navigate a way out of chaos. Syst. Eng. Procedia 2012, 3, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poutanen, P.; Soliman, W.; Ståhle, P. The complexity of innovation: An assessment and review of the complexity perspective. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 19, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, S.M. Simplifying complexity: A review of complexity theory. Geoforum 2001, 32, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickles, D.; Hawe, P.; Shiell, A. A simple guide to chaos and complexity. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, M.; Giddings, M.M. A simple approach to complexity theory. J. Soc. Work Educ. 2012, 48, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proches, C.G.; Bodhanya, S. Exploring stakeholder interactions through the lens of complexity theory: Lessons from the sugar industry. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 2507–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, C.P. Cooperative supply chain management: The impact of interorganizational information systems. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 1995, 4, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surana, A.; Kumara, S.; Greaves, M.; Raghavan, U.N. Supply-chain networks: A complex adaptive systems perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 4235–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, J.A.; Davis, D.; Stock, J.; Monahan, L. Exploring the processing of product returns from a complex adaptive system perspective. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, L.; Bruce, K.; Rolfe, I. Adapt fast or die slowly: Complex adaptive business models at Cisco Systems. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 77, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, F.R. A complexity perspective on logistics management: Rethinking assumptions for the sustainability era. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2019, 30, 681–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katayama, H.; Bennett, D. Agility, adaptability and leanness: A comparison of concepts and a study of practice. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1999, 60, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.; Churchhouse, S.; Hoffman, J.; Palermo, A. Using scenario planning to reshape strategy. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2017, 58, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Stepchenko, D.; Voronova, I. Investigation of Insurance Company Financial Stability: Case of Baltic Non-Life Insurance Market. In Proceedings of the No: Business and Management: 8th International Scientific Conference, Lietuva, Vilnius, 3 July 2014; Volume 15, p. 16. Available online: https://scholar.archive.org/work/t3ibmeyrojg53gbdc6nl23shwy/access/wayback/http://www.bm.vgtu.lt:80/index.php/bm/bm_2014/paper/viewFile/220/488 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Longenecker, C.O.; Neubert, M.J.; Fink, L.S. Causes and consequences of managerial failure in rapidly changing organizations. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Zimmermann, A.; Raisch, S. How do firms adapt to discontinuous change? Bridging the dynamic capabilities and ambidexterity perspectives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.F.; Garg, S. Adaptability of Manufacturing Operations through Digital Twins. 2021. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/130954 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Evans, C.R.; Dion, K.L. Group cohesion and performance: A meta-analysis. Small Group Res. 1991, 22, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøgaard, B.; Rygh, A.; Benito, G.R. Bringing corporate governance into internalization theory: State ownership and foreign entry strategies. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2019, 50, 1310–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M. Leveraging the International Context: Essays on Building Offshoring Capabilities and Enhancing Firm Innovation; No. EPS-2015-357-LIS. 2015. Available online: https://repub.eur.nl/pub/78688/ (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Hulland, J.; Houston, M.B. Why Systematic Review Papers and Meta-Analyses Matter: An Introduction to the Special Issue on Generalizations in Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahimian, S.; ShamiZanjani, M.; Manian, A.; Esfiddani, M.R. Developing a Customer Experience Management Framework in Hoteling Industry: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Foundations. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 523–547. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahiya, E.T. Five decades of research on export barriers: Review and future directions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 1172–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Serrano, A.; Paul, J.; Dikova, D. International franchising: A literature review and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 238–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Feliciano-Cestero, M.M. Five decades of research on foreign direct investment by MNEs: An overview and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, J.; Benito, G.R. A review of research on outward foreign direct investment from emerging countries, including China: What do we know, how do we know and where should we be heading? Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2018, 24, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randhawa, K.; Wilden, R.; Hohberger, J. A bibliometric review of open innovation: Setting a research agenda. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 750–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Maley, J.; Dana, L.P.; Novak, I.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Caputo, A. Pathways of SME internationalization: A bibliometric and systematic review. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, V.; Rajan, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Lecinski, J. Understanding the role of artificial intelligence in personalized engagement marketing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D.; Van Aken, J.E. Developing design propositions through research synthesis. Organ. Stud. 2008, 29, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinjing, W.A.N.G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chenling, F.U.; Zhang, X. Progress in urban metabolism research and hotspot analysis based on CiteSpace analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 281, 125224. [Google Scholar]

- Rialp, A.; Merigó, J.M.; Cancino, C.A.; Urbano, D. Twenty-five years (1992–2016) of the international business review: A bibliometric overview. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRyalat, S.A.S.; Malkawi, L.W.; Momani, S.M. Comparing bibliometric analysis using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 152, e58494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Wang, X. Methodological function of CiteSpace knowledge graph. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2015, 33, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, T.; Talib, N.B.A. Hot Topics and Emerging Trends in Business Model Innovation Research Based on Citespace. Int. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 2200–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimin, L.; Jing, L. Research Hotspot Analysis of EPC Pattern Based on CiteSpace in China. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 253, p. 02046. Available online: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs/2021/29/e3sconf_eem2021_02046/e3sconf_eem2021_02046.html (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- CHI, P.J.; Wu, M. Competitive situation analysis of transgenic rice subject. China Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 116–123. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, J.; Shen, Y. Gambling and marketing: A systematic literature review using HistCite. Account. Financ. 2021, 61, 2837–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, C.T.; Garavan, T.N. Human resource development in SMEs: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Chugh, H. Entrepreneurial learning: Past research and future challenges. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Widyawati, L. A systematic literature review of socially responsible investment and environmental social governance metrics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2005, 83, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Messeghem, K.; Bakkali, C.; Sammut, S.; Swalhi, A. Measuring nonprofit incubator performance: Toward an adapted balanced scorecard approach. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2018, 56, 658–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, B.A. Strategic type, market orientation, and the balance between adaptability and adaptation. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 45, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, D.O.; Varadarajan, P.R.; Pride, W.M. Strategic adaptability and firm performance: A market-contingent perspective. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallikas, J.; Karvonen, I.; Pulkkinen, U.; Virolainen, V.M.; Tuominen, M. Risk management processes in supplier networks. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 90, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Jones, C.D.; Binyamin, G. The power of caring and generativity in building strategic adaptability. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2016, 89, 46–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worley, C.G.; Lawler, E.E. Agility and organization design: A diagnostic framework. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, M.S.; Nash, D.P. What corporations do with foresight. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2014, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringland, G. The role of scenarios in strategic foresight. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2010, 77, 1493–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Rojas, J.L. Procedimiento Para la Elaboración de un Análisis FODA como una Herramienta de Planeación Estratégica en las Empresas. 2017. Available online: https://cmapspublic2.ihmc.us/rid=1SWJY4H3P-1DLBBJD-3DWN/ANALISIS%20DOFA.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.G. Critical Infrastructure Protection in Homeland Security: Defending a Networked Nation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=Yz6-DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA15&ots=eX9aN5wkcl&sig=_f4fiLqmcr_NMmTOKYA5SpDRJRE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Mousavi, S.; Gigerenzer, G. Heuristics are tools for uncertainty. Homo Oeconomicus 2017, 34, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agarwal, A.; Shankar, R.; Tiwari, M.K. Modeling the metrics of lean, agile and leagile supply chain: An ANP-based approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 173, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongzon, J.; Heng, W. Port privatization, efficiency and competitiveness: Some empirical evidence from container ports (terminals). Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R.; Janovics, J.; Young, J.; Cho, H.J. Diagnosing organizational cultures: Validating a model and method. Doc. De Trab. Denison Consult. Group 2006, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Milne, A. What is in it for us? Network effects and bank payment innovation. J. Bank. Financ. 2006, 30, 1613–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.W.; Wong, C.Y.; Boon-itt, S. The combined effects of internal and external supply chain integration on product innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 146, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Du, B. Digital advertising and company value: Implications of reallocating advertising expenditures. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, L.; Vegholm, F. The dyadic bank-SME relationship: Customer adaptation in interaction, role and organisation. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2009, 16, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalkowski, C.; Kindström, D.; Alejandro, T.B.; Brege, S.; Biggemann, S. Service infusion as agile incrementalism in action. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weigelt, C.; Sarkar, M.B. Performance implications of outsourcing for technological innovations: Managing the efficiency and adaptability trade-off. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby, M.E. Environmental management in development: The evolution of paradigms. Ecol. Econ. 1991, 3, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P.; Sever, J.M. Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Highhouse, S.; Brooks, M.E.; Gregarus, G. An organizational impression management perspective on the formation of corporate reputations. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorshkova, L.A.; Trifonov, Y.V.; Poplavskaya, V.A. Ensuring adaptability of a company using life cycle theory. Life Sci. J. 2014, 11, 705–708. [Google Scholar]

- Deverell, E.; Olsson, E.K. Organizational culture effects on strategy and adaptability in crisis management. Risk Manag. 2010, 12, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, R.E.; Snow, C.C.; Meyer, A.D.; Coleman, H.J., Jr. Organizational strategy, structure, and process. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1978, 3, 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, I.; Ebers, M. Dynamics of social capital and their performance implications: Lessons from biotechnology start-ups. Adm. Sci. Q. 2006, 51, 262–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.L. In the market but not of it: Fair trade coffee and forest stewardship council certification as market-based social change. World Dev. 2005, 33, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, A. Re-reengineering the dream: Agility as competitive adaptability. Int. J. Agil. Syst. Manag. 2014, 7, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, E. Hedonic and utilitarian shopping goals: A decade later. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2018, 28, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarillo, J.C. On strategic networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 1988, 9, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayanni, D.A. A model of interorganizational networking antecedents, consequences and business performance. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2015, 22, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miers, D. Process Innovation and Corporate Agility Balancing Efficiency and Adaptability in a Knowledge-Centric World. BP Trends 2010. Available online: https://www.bptrends.com/bpt/wp-content/publicationfiles/FOUR%2001-10-ART-ProcessInnovationCorporateAgility-Miers.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Lévárdy, V.; Browning, T.R. An adaptive process model to support product development project management. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2009, 56, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.H.; Kremer, G.E.O.; Wysk, R.A. A dynamic programming method for product upgrade planning incorporating technology development and end-of-life decisions. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2017, 34, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijsdijk, S.A.; Hultink, E.J. How today’s consumers perceive tomorrow’s smart products. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2009, 26, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieh, O.E.; Jarzabek, S. An adaptability-driven model and tool for analysis of service profitability. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 13–17 June 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.L.; Collins, R.W.; Hevner, A.R. Control of flexible software development under uncertainty. Inf. Syst. Res. 2009, 20, 400–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pehlken, A.; Qian, H.; Hong, Z. A systematic adaptable platform architecture design methodology for early product development. J. Eng. Des. 2016, 27, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartline, M.D.; Ferrell, O.C. The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, M.; Schröder, S. Transforming human resources in the new economy: Developing the next generation of global HR managers at Deutsche Bank AG. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 40, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, K.; Whitworth, B.; Fjermestad, J.; Mahindra, E. Leading IT Flexibility: Anticipation, Agility and Adaptability; AMCIS: Atlanta, Georgia, 2005; Volume 361, Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1862&context=amcis2005. (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Bell, B.S.; Kozlowski, S.W. Active learning: Effects of core training design elements on self-regulatory processes, learning, and adaptability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ito, J.K.; Brotheridge, C.M. Does supporting employees’ career adaptability lead to commitment, turnover, or both? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haynie, M.; Shepherd, D.A. A measure of adaptive cognition for entrepreneurship research. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M.; Harry, N. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of employees’ career adaptability. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 84, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yao, L.; Sun, A.; Tay, Y. Deep learning based recommender system: A survey and new perspectives. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 52, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kozlowski, S.W.; Gully, S.M.; Brown, K.G.; Salas, E.; Smith, E.M.; Nason, E.R. Effects of training goals and goal orientation traits on multidimensional training outcomes and performance adaptability. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 85, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, L.; Ginevra, M.C.; Soresi, S. The Career and Work Adaptability Questionnaire (CWAQ): A first contribution to its validation. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Lichtenstein, B.B. The role of organizational learning in the opportunity–recognition process. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. Insights into triple bottom line integration from a learning organization perspective. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2006, 12, 809–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.S.; Kanar, A.M.; Kozlowski, S.W. Current issues and future directions in simulation-based training in North America. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabiu, A.; Pangil, F.; Othman, S.Z. Does training, job autonomy and career planning predict employees’ adaptive performance? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 21, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F.; Osborne, K.; Manning, I. Organization–environment adaptation: A macro- level shift in modeling work distress and morale. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baard, S.K.; Rench, T.A.; Kozlowski, S.W. Performance adaptation: A theoretical integration and review. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 48–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.M.; Rabbani, M.; Dipal, D.D.; Zarif, M.I.I.; Iqbal, A.; Schwichtenberg, A.; Ahamed, S.I. Informing Developmental Milestone Achievement for Children with Autism: Machine Learning Approach. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Faraj, S.; Sims, H.P., Jr. Contingent leadership and effectiveness of trauma resuscitation teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R.; McKelvey, B. Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmeli, A.; Gelbard, R.; Gefen, D. The importance of innovation leadership in cultivating strategic fit and enhancing firm performance. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannah, S.T.; Balthazard, P.A.; Waldman, D.A.; Jennings, P.L.; Thatcher, R.W. The psychological and neurological bases of leader self-complexity and effects on adaptive decision- making. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannessen, S.; Aasen, T.M.B. Exploring innovation processes from a complexity perspective. Part I: Theoretical and methodological approach. Int. J. Learn. Chang. 2007, 2, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Marion, R. Complexity leadership in bureaucratic forms of organizing: A meso model. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stachowski, A.A.; Kaplan, S.A.; Waller, M.J. The benefits of flexible team interaction during crises. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramos-Villagrasa, P.J.; Passos, A.M.; García-Izquierdo, A.L. From Planning to Performance: The Adaptation Process as a Determinant of Outcomes. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2019, 55, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salas, E.; Sims, D.E.; Burke, C.S. Is there a “big five” in teamwork? Small Group Res. 2005, 36, 555–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnell, C.A.; Ou, A.Y.; Kinicki, A. Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’s theoretical suppositions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Detzen, N.; Verbeeten, F.H.; Gamm, N.; Möller, K. Formal controls and team adaptability in new product development projects. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C.; Ang, S. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2003; Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/1405871 (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Şahin, F.; Gurbuz, S.; Köksal, O. Cultural intelligence (CQ) in action: The effects of personality and international assignment on the development of CQ. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2014, 39, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh Magsi, H.; Ong, T.S.; Ho, J.A.; Sheikh Hassan, A.F. Organizational culture and environmental performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dougherty, D. Managers fail to innovate and academics fail to explain how. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2018, 14, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristiansen, S.; Kimeme, J.; Mbwambo, A.; Wahid, F. Information flows and adaptation in Tanzanian cottage industries. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2005, 17, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, E.; Malhotra, Y. Integrating knowledge management technologies in organizational business processes: Getting real time enterprises to deliver real business performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Di Stefano, G.; Gambardella, A.; Verona, G. Technology push and demand pull perspectives in innovation studies: Current findings and future research directions. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, I.P.; Tsinopoulos, C.; Allen, P.; Rose-Anderssen, C. New product development as a complex adaptive system of decisions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 23, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Speier-Pero, C. Data science, predictive analytics, and big data in supply chain management: Current state and future potential. J. Bus. Logist. 2015, 36, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarini, B.; Scaramozzino, P. Production complexity, adaptability and economic growth. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2016, 37, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID Number | Reference |

|---|---|

| 125 | LePine, J. A., Colquitt, J. A., & Erez, A. (2000). Adaptability to changing task contexts: Effects of general cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Personnel Psychology, 53(3), 563–593. |

| 121 | Pulakos, E. D., Arad, S., Donovan, M. A., & Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4), 612. |

| 142 | Kozlowski, S. W., Gully, S. M., Brown, K. G., Salas, E., Smith, E. M., & Nason, E. R. (2001). Effects of training goals and goal orientation traits on multidimensional training outcomes and performance adaptability. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 85(1), 1–31. |

| 88 | Grabher, G., & Stark, D. (1997). Organizing diversity: evolutionary theory, network analysis and postsocialism. Regional Studies, 31(5), 533–544. |

| 46 | Gordon, G. G., & DiTomaso, N. (1992). Predicting corporate performance from organizational culture. Journal of Management Studies, 29(6), 783–798. |

| 1292 | Dubey, R., Altay, N., Gunasekaran, A., Blome, C., Papadopoulos, T., & Childe, S. J. (2018). Supply chain agility, adaptability and alignment: empirical evidence from the Indian auto components industry. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. |

| 850 | Baard, S. K., Rench, T. A., & Kozlowski, S. W. (2014). Performance adaptation: A theoretical integration and review. Journal of Management, 40(1), 48–99. |

| 980 | Schoenherr, T., & Speier-Pero, C. (2015). Data science, predictive analytics, and big data in supply chain management: Current state and future potential. Journal of Business Logistics, 36(1), 120–132. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Fong, P.S.-W.; Yamoah Agyemang, D. What Should Be Focused on When Digital Transformation Hits Industries? Literature Review of Business Management Adaptability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313447

Zhang Y, Fong PS-W, Yamoah Agyemang D. What Should Be Focused on When Digital Transformation Hits Industries? Literature Review of Business Management Adaptability. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313447

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yi, Patrick Sik-Wah Fong, and Daniel Yamoah Agyemang. 2021. "What Should Be Focused on When Digital Transformation Hits Industries? Literature Review of Business Management Adaptability" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313447

APA StyleZhang, Y., Fong, P. S.-W., & Yamoah Agyemang, D. (2021). What Should Be Focused on When Digital Transformation Hits Industries? Literature Review of Business Management Adaptability. Sustainability, 13(23), 13447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313447