Peruvian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Times of Crisis—Or What Is Happening over Time?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Background

2.1. Crisis and Crisis Management

2.2. Responses to Crises in SMEs

2.3. Crisis Management in SMEs

2.4. Crisis Management in Latin America

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Peru and COVID-19

4.2. Interview Findings

4.2.1. How Would You Describe the Current Situation of the Company?

4.2.2. What Have You Done to Cope with the Pandemic since the Interview at the End of April?

4.2.3. Have You Been Required to Adapt the Business Model Due to the Pandemic?

4.2.4. Have You Started Implementing CM-Related Measures? If Yes, Which Ones?

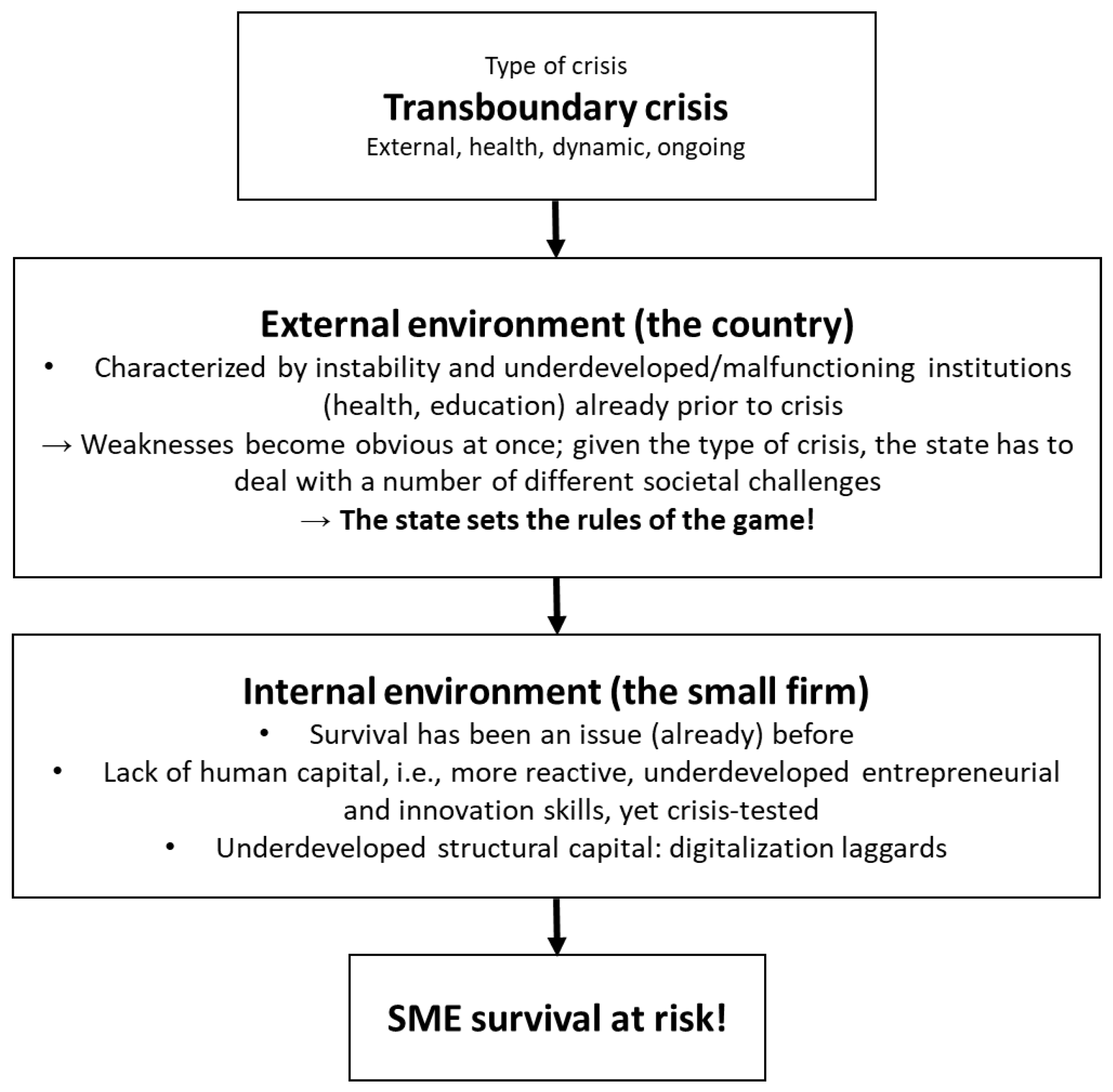

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations

6.4. Future Research Avenues

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Interviewee | Size of Company | Industry/Sector | Year of Foundation | Position in the Company | Educational Background | Gender | Impact of COVID-19 in April 2020 * | Impact of COVID-19 in December 2020¤ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Micro | Poultry (eggs) Production | 2019 | Founder and operations manager | Non-university degree | Female | - | + |

| 2 | Micro | Food/Catering Service | 2014 | Owner and commercial manager | University degree | Female | - | - |

| 3 | Micro | Sale of software and hardware telecommunication Service | 2015 | Owner | University degree | Male | - | - |

| 4 | Small | Coffee machine vending and maintenance Service | 2013 | In charge of accounting | University degree | Female | - | - |

| 5 | Micro | Veterinary Service | 2019 | Owner and General manager | University degree | Female | - | + |

| 6 | Micro | HR Consulting Service | 2018 | Owner | University degree | Female | - | + |

| 7 | Small | Plastic bags Production | 2000 | In charge of creditors | University degree | Female | + | + |

| 8 | Micro | Accounting Consulting Service | 2013 | Owner | University degree | Male | - | +/- |

| 9 | Micro | Cleaning Service | 2018 | Foreman | No formal education | Male | + | + |

| 10 | Micro | Football classes Service | 2017 | Owner | University degree | Male | - | - |

| 11 | Micro | Innovation Consulting Service | 2015 | Owner | University degree | Male | - | +/- |

| 12 | Micro | HR Consulting Service | 2017 | Owner | University degree | Female | - | + |

| 13 | Medium-sized | Production of additives for machines Production | 1901 | Process manager | University degree | Female | - | +/- |

| 14 | Medium-sized | Temporary employment agency Service | 1963 | Head of HR | University degree | Female | - | |

| 15 | Medium-sized | Security Service | 1968 | Head of HR | University degree | Female | +/- | |

| 16 | Micro | Wood toys Production | 2017 | Founder | Non-university degree | Male | - | |

| 17 | Medium-sized | Business and Accounting Consultant Service | 2006 | Key account manager | University degree | Female | - | +/- |

| 18 | Micro | HR Consulting Service | 2010 | Founder and general manager | University degree | Male | - | - |

| 19 | Medium-sized | Cargo Transportation Service | 2010 | Traffic controller | University degree | Male | - | +/- |

| 20 | Micro | Psychological counselling Service | 2014 | Founder | University degree | Female | + | + |

| 21 | Small | Sale of HRM software Service | 2010 | Purchasing manager | University degree | Female | - | |

| 22 | Medium-sized | Sale of mining machines and maintenance Service | 1957 | Head of maintenance | University degree | Male | - | +/- |

| 23 | Medium-sized | Engineering construction Service | 2008 | Project coordinator | University degree | Female | - | +/- |

| 24 | Medium-sized | Fishery Production | 1950 | Head of logistics | University degree | Female | - | - |

| 25 | Medium-sized | Sale of shoes and fashion Service | 2009 | Head of HR | University degree | Female | - |

References

- Kuckertz, A.; Brändle, L.; Gaudig, A.; Hinderer, S.; Morales, R.; Prochotta, A.; Steinbrink, M.; Berger, E. Startups in times of crisis—A rapid response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 13, e00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Henschel, T. COVID-19 as an accelerator for developing strong(er) businesses? Insights from Estonian small firms. J. Int. Counc. Small Bus. 2021, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbane, B. Small business research: Time for a crisis-based view. Int. Small Bus. J. 2021, 28, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kücher, A.; Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B. Organizational failure and decline—A bibliometric study of the scientific frontend. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Eden, L.; Bemish, P.W. Caught in the crossfire: Dimensions of vulnerability and foreign multinationals’ exit from war-afflicted countries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1478–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, T.C. Crisis leadership in economic recession: A three-barrier approach to offset external constraints. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P.; Huang, C.; Li, B. Crisis management for SMEs: Insights from a multiple-case study. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2012, 5, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbane, B. Exploring crisis management in UK small- and medium-sized Enterprises. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2013, 21, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Clauss, T.; Breier, M.; Gast, J.; Zardini, A.; Tiberius, V. The economics of COVID-19: Initial empirical evidence on how family firms in five European countries cope with the corona crisis. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1067–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers, F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J.A.; Crandall, W.R. What drived crisis readiness? An assessment of managers in the United States: The effects of market turbulence, perceived likelihood of a crisis, small- to medium-sized enterprises and innovative capacity. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2021, 29, 416–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.; Gordon, S. Much ado about nothing? The surprising persistence of nascent entrepreneurs through macroeconomic crisis. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2016, 40, 915–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López-Calva, L.F. Small Businesses, Big Impacts: Supporting Productive SMEs as an Engine of Recovery in LAC. 2021. Available online: https://www.latinamerica.undp.org/content/rblac/en/home/presscenter/director-s-graph-for-thought/small-businesses--big-impacts--supporting-productive-smes-as-an-.html (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Fernandes, N. Economic Effects of Coronavirus Outbreak (COVID-19) on the World Economy. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. SSRN Sch. 2020, 3557504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayour, F.; Adongo, C.A.; Amuquandoh, F.E.; Adam, I. Managing the COVID-19 crisis: Coping and post-recovery strategies for hospitality and tourism businesses in Ghana. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2020, 4, 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W.T. Crisis Management and Communications; University of Florida, Institute for Public Relations: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, J.C.; Lok, T.C.; Luo, Y.; Hao, W. Crisis challenges of small firms in Macao during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Bus. Res. China 2020, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Laufer, D. How does crisis management in China differ from the West? A review of the literature and directions for future research. J. Int. Manag. 2020, 2, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission of the European Communities. Commission recommendation concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Off. J. Eur. Union 2005, L124, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cater, J.J.; Beal, B. Ripple effects on family firms from an externally induced crisis. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2014, 4, 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.A.; Woods, C.L.; Staricek, N.C. Restorative rhetoric and social media: An examination of the Boston Marathon bombing. Commun. Stud. 2017, 68, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, J.; Pfarrer, M.D.; Short, C.E.; Coombs, W.T. Crises and Crisis Management: Integration, Interpretation, and Research Development. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1661–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reilly, A. Are organizations ready for a crisis? A managerial scorecard. Columbia J. World Bus. 1987, 25, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, J.; Peng, J.; Lu, L. The perceived impact of the Covid-19 epidemic: Evidence from a sample of 4807 SMEs in Sichuan Province, China. Environ. Hazards 2020, 19, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascio, F.D.; Natalini, A.; Cacciatore, F. Public Administration and Creeping Crises: Insights from COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaccini, M.; Saccani, N.; Kowalkowski, C.; Paiola, M.; Adrodegari, F. Navigating disruptive crises through service-led growth: The impact of COVID-19 on Italian manufacturing firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (covid-19) and entrepreneurship: Changing life and work landscape. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020, 32, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiyevskyy, O.; Shirokova, G.; Ritala, P. Exploration and exploitation in crisis environment: Implications for level and variability of firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 114, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.; Riley, D. School leadership in times of crisis. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2012, 32, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Stanske, S.; Lieberman, M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, V7–V18. [Google Scholar]

- Polyviou, M.; Croxton, K.L.; Knemeyer, A.M. Resilience of medium-sized firms to supply chain disruptions: The role of internal social capital. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2020, 40, 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorgren, S.; Williams, T.A. Staying alive during an unfolding crisis: How SMEs ward off impending disaster. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 14, e00187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyono, A.; Moin, A.; Putri, V.N.A.O. Identifying digital transformation paths in the business model of SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, S.; Koporcic, N.; Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Kadic-Maglajlic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Islam, N. Business-to-business open innovation: COVID-19 lessons for small and medium-sized enterprises from emerging markets. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 170, 120883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Moog, P.; Schlepphorst, S.; Raich, M. Crisis and turnaround management in SMEs: A qualitative-empirical investigation of 30 companies. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2013, 5, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghfouri, P.; Kraiczy, N.D.; Hack, A.; Kellermanns, F.W. Ready for a crisis? How supervisory boards affect the formalized crisis procedures of small and medium-sized family firms in Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2015, 9, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, R. Entrepreneurship and crisis management: The experiences of small businesses during the London 2011 riots. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branicki, L.; Sullivan-Taylor, B.; Livschitz, R. How entrepreneurial resilience generates resilient SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 1244–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucaktürk, A.; Bekmezci, M.; Ucaktürk, T. Prevailing during the periods of economical crisis and recession through business model innovation. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caballero-Morales, S.-O. Innovation as recovery strategy for SMEs in emerging economies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 57, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrish, S.; Jones, R. Post-disaster business recovery: An entrepreneurial marketing perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thukral, E. COVID-19: Small and medium enterprises challenges and responses with creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship. Strateg. Chang. 2021, 30, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, V.B.; Todesco, J.L. COVID-19 crisis and SMEs responses: The role of digital transformation. Knowl. Process. Manag. 2021, 28, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Sultan, W.I.M. Women MSMEs in times of crisis: Challenges and opportunities. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2020, 27, 1069–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmer, K.L. Democracy and Economic Crisis: The Latin American Experience. World Politics 1990, 42, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M. Venezuelan economic crisis: Crossing Latin American and Caribbean borders. Migr. Dev. 2019, 8, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T. Exchange rate regimes and monetary cooperation: Lessons from East Asia and Latin America. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2004, 55, 240–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, J.A.; Gannon, G.L.; Thuraisamy, K.S. Sovereign risk and the impact of crisis: Evidence from Latin America. J. Bank. Financ. 2017, 77, 328–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galafassi, G.P. Ecological Crisis, Poverty and Urban Development in Latin America. Democr. Nat. 2002, 8, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liodakis, G. Capital, Economic Growth, and Socio-Ecological Crisis: A Critique of De-Growth. Int. Crit. Thought 2018, 8, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.A. Latin America’s New Turbulence: Crisis and Integrity in Brazil. J. Democr. 2016, 27, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, J.A. Crisis Management and Strategic Orientation in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in Peru, Mexico and the United States. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2015, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vidal, G.; Guzmán-Vilar, L.; Sánchez-Rodriguez, A.; Martinez-Vivar, R.; Pérez-Campdesuñer, R.; Uset-Ruiz, F. Facing post COVID-19 era, what is really important for Ecuadorian SMEs? Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Perez, M.A.; Mohieldin, M.; Hult, G.T.M.; Velez-Ocampo, J. COVID-19, sustainable development challenges of Latin America and the Caribbean, and the potential engines for an SDGs-based recovery. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2021, 19, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejárraga, I.; Rizzo, H.L.; Oberhofer, H.; Stone, S.; Shepherd, B. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Global Markets: A Differential Approach for Services; OECD Trade Policy Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014; No. 165. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre Executive Summary. COVID-19: The Great Lockdown and Its Impact on Small Business. 2020. Available online: https://www.intracen.org/uploadedFiles/intracenorg/Content/Publications/ITC_SMECO-2020ExSummmary_EN_web.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Maykut, P.; Morehouse, R. Beginning Qualitative Research. A Philosophic and Practical Guide; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.C.; Ketchen, D.J.; Combs, J.G.; Ireland, R.D. Research methods in entrepreneurship. Organ. Res. Methods 2010, 13, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C. Processes of a case study methodology for postgraduate research in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 1998, 32, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, L. Thematic coding and analysis. Sage Encycl. Qual. Res. Methods 2008, 1, 868–876. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. An Expanded Sourcebook, Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Salud. 2020. Available online: www.minsal.cl (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- World Health Organization. 2021. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/pe (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- International Labor Organization (ILO). Lima’s Gamarra Market: The Benefits of Moving to the Formal Economy. 2019. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_723278/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- The Wire. In Peru, the Political Elite’s Lack of Accountability Made It Necessary for the Streets to Riseh. 2020. Available online: https://thewire.in/rights/peru-protests-martin-vizcarra-manuel-merino (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Doern, R.; Williams, N.; Vorley, T. Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: Business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N.; Kelley, N. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018/2019 Global Report. 2019. Available online: http://www.gemconsortium.org/report (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Manimala, M.J.; Wasdani, K.P. Emerging Economies: Muddling Through to Development. In Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: Perspectives from Emerging Economies; Manimala, M.J., Wasdani, K.P., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2015; pp. 3–53. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Durst, S.; Svensson, A.; Palacios Acuache, M.M.G. Peruvian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Times of Crisis—Or What Is Happening over Time? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413560

Durst S, Svensson A, Palacios Acuache MMG. Peruvian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Times of Crisis—Or What Is Happening over Time? Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413560

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurst, Susanne, Ann Svensson, and Mariano Martin Genaro Palacios Acuache. 2021. "Peruvian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Times of Crisis—Or What Is Happening over Time?" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413560

APA StyleDurst, S., Svensson, A., & Palacios Acuache, M. M. G. (2021). Peruvian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Times of Crisis—Or What Is Happening over Time? Sustainability, 13(24), 13560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413560