Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the conditions for tourism’s development in the region located at the external border of the European Union?

- What are the conditions for development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in tourism at the external border of the European Union?

- Which actors shape the entrepreneurial ecosystem in tourism at the external border of the European Union?

- How does the presence of the external border of the European Union influence the development of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in tourism?

2. Scientific Background

2.1. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

2.2. Border Areas as Tourism Development Terrains

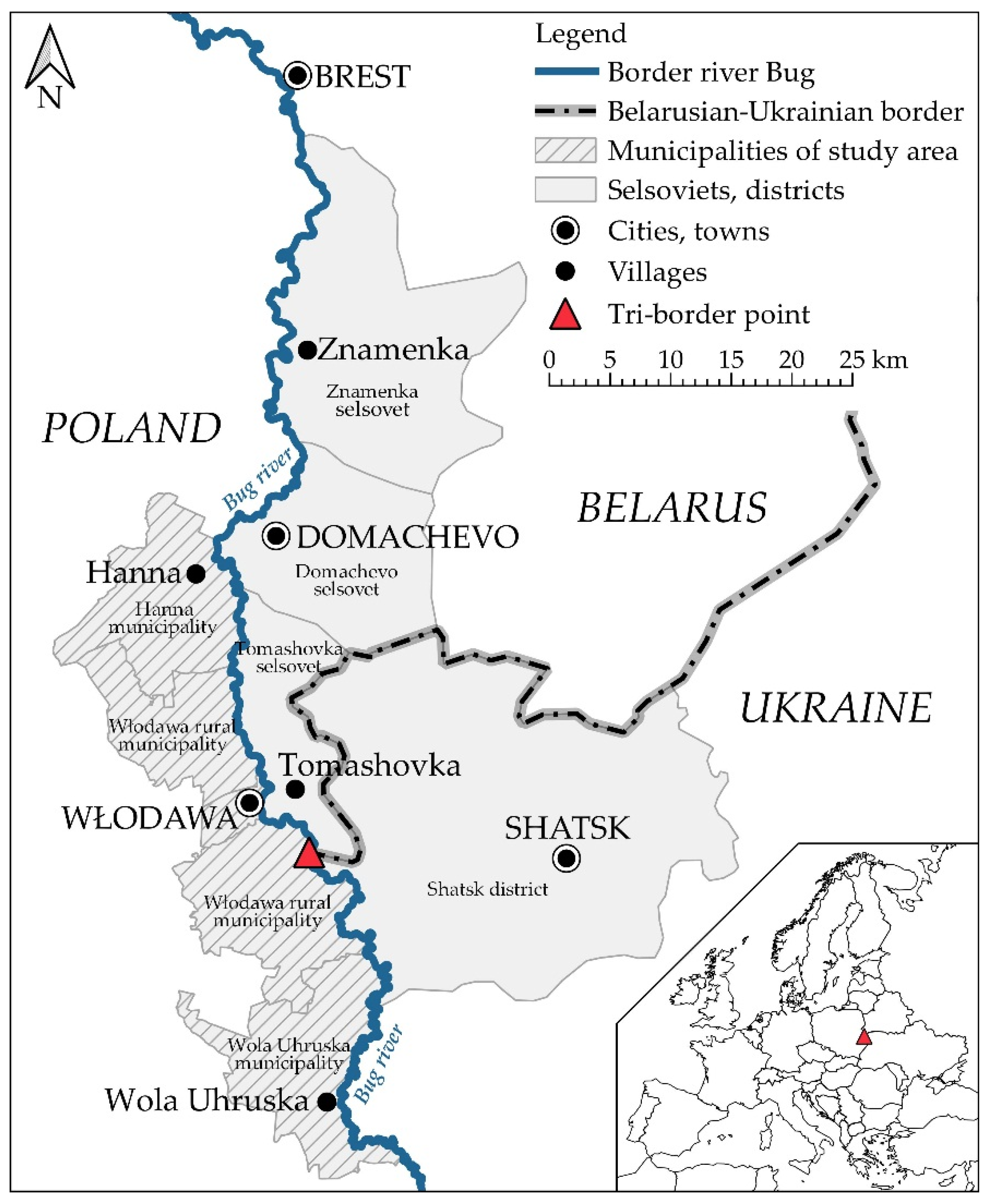

3. Research Area

3.1. Delimitation

3.2. Tourism Characteristics

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Borders and the Development of Tourism at the Polish–Belarusian–Ukrainian Border Area

5.2. Conditions for the Development of an Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in the Polish Part of the Tri-Border Area

5.2.1. Demographic Conditions

5.2.2. Transport Availability

5.3. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in the Polish Part of the Tri-Border Area

5.3.1. Local Governments

5.3.2. Public Institutions

5.3.3. Non-Governmental Organisations

5.3.4. Actions of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Actors and the Level of Tourist Traffic

5.4. Development of Entrepreneurship in Tourism

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Timothy, D.J. Political Boundaries and Tourism: Borders as Tourist Attraction. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Tourism and Political Boundaries; Routledge Advances in Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kałuski, S. Blizny Historii. Geografia Granic Politycznych Współczesnego Świata (History Scars. Geography of the Political Boundaries of the Contemporary World); Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Więckowski, M. How Border Tripoints Offer Opportunities for Transboundary Tourism Development. Tour. Geogr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbman, A.; Timothy, D.J. From Hostile Boundaries to Tourist Attractions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóhanesson, G.T.; Huijbens, E.H. Tourism in Times of Crisis: Exploring the Discourse of Tourism Development in Iceland. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałuski, S. Border Tri-points as Transborder Cooperation Regions in Central and Eastern Europe. In Regional Trans-Border Co-Operation in Countries of Central and Eastern Europe—A Balance of Achievements; Geopolitical Studies; Kitowski, J., Ed.; Geopolitical Studies: Warsaw, Poland, 2006; Volume 14, pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Saarinen, J. Cross-border Cooperation and Tourism in Europe. In Trends in European Tourism Planning and Organization; Costa, C., Panyik, E., Buhalis, D., Eds.; Channel View Publication: Bristol, UK, 2013; pp. 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Więckowski, M. Turystyka na Obszarach Przygranicznych Polski (Tourism in the Border-adjacent Areas of Poland); Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Anisiewicz, R. Condition for Tourist Development in the Tri-border Area of Poland, Belarus and Ukraine. Geogr. Tour. 2019, 7, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Journal of European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2006/962 (accessed on 4 August 2021).

- Dubini, P. The Influence of Motivations and Environment on Business Startups: Some Hints for Public Policies. J. Bus. Ventur. 1989, 4, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, E.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy. In Sage Handbook for Entrepreneurship and Small Business; Blackburn, R., De Clerq, D., Heinonen, J., Wang, Z., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. Final Rep. OECD 2014, 30, 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D.J. How to Start an Entrepreneurial Revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D.J. The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship; Institute of International European Affairs: Dublin, Ireland, 2011; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.C.; Malin, S. Green Entrepreneurship: A Method for Managing Natural Resources? Soc. Nat. Resour. Int. J. 2008, 21, 828–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörish, J. The Role of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Sustainability Transitions: A Conceptual Synthesis Against the Background of the Multi-level Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2015, 5, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J.; Chmieliński, J.; Czapiewski, K.; Mazur, M.; Szymańska, M.; Wilkin, J. Przedsiębiorczość na Wsi—Współczesne Wyzwania i Koncepcje Rozwoju. (Entrepreneurship in the Countryside—Contemporary Challenges and the Concept of Development); Fundacja na rzecz Rozwoju Polskiego Rolnictwa: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Panfiluk, E. Problemy Zrównoważonego Rozwoju w Turystyce (Problems of the Sustainable Development of Tourism). Econ. Manag. 2011, 2, 60–72. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sofield, T.H.B. Border Tourism and Border Communities. An Overview. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumsdon, L.; Page, S. Tourism and Transport: Issues and Agenda for the New Millennium; Advances in Tourism Research Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Khadaroo, J.; Seetanah, B. Transport Infrastructure and Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Dev. 2007, 34, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. Relacje Zachodzące między Rozwojem Transportu Lotniczego a Rozwojem Turystyki (Relations beetwen the Development of Air Transport and the Development of Tourism). In Współczesne Uwarunkowania i Problemy Rozwoju Turystyki (Contemporary Conditions and Problems of Tourism Development); Pawlusiński, R., Ed.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej, Uniwersytet Jagielloński: Cracow, Poland, 2013; pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Solvoll, S.; Alsos, G.; Bulanova, O. Tourism Entrepreneurship—Review and Future Directions. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 15 (Suppl. S1), 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.Y. Tourism Entrepreneurship: People, Places and Processes. Tour. Anal. 2006, 11, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.Y.; Hatten, T.S. The Tourism Entrepreneur: The Overlooked Player in Tourism Development Studies. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2002, 3, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.; Hao, H.; Alderman, D.; Kleckley, J.W.; Gray, S. A Spatial Analysis of Tourism Entrepreneurship and the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in North Carolina, USA. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, F.E.; Duxbury, N.; Vinagre de Castro, T. Creative Tourism: Catalyzing Artisan Entrepreneur Networks in Rural Portugal. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari Samani, N.; Badri, S.A.; Rezvani, M.R. Performance Evaluation of Elements of Rural Tourism Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. Case Study: Teheran Province. J. Rural. Res. 2020, 11, 565–575. (In Persian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloaloa, J. Extent of Influence of Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Elements (E3) on Entrepreneurial and Tourism Activities among Beach Resorts Entrepreneurs in Ilocos Norte. Asian J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2019, 2, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Matznetter, J. Border and Tourism: Fundamental Relations. In Tourism and Borders: Proceedings of the Meeting of the IGU Working Group—Geography of Tourism and Recreation; Gruber, G., Lamping, H., Eds.; Institute für Wirtschafts-und Sozialgeographie der Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität: Frankfurt, Germany, 1979; pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Relationships between Tourism and International Boundaries. In Tourism and Borders: Contemporary Issues, Policies and International Research; Wachowiak, H., Ed.; Ashgate Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2006; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska, A. Fundusze Unijne dla Zrównoważonej Turystyki na Obszarach Natura 2000 (EU Funds for Sustainable Tourism in Natura 2000 Areas). Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu 2008, 2, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Barwiński, M. Geographical and Sociological Aspects of Borderland—An Outline of Main Issues. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Geogr.-Oeconomica 2002, 4, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, J.K.S. The Making of an Attraction: The Case of North Cape. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Shopping Tourism, Retailing and Leisure; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Butler, R.W. Cross-border Shopping: Canada and the United States. In Borders and Border Politics in Globalizing World; Ganster, P., Lorey, D.E., Eds.; SR Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2005; pp. 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Szytniewski, B.B.; Spierings, B.; van der Velde, M. Socio-cultural Proximity, Daily Life and Shopping Tourism in the Dutch-German Border Region. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bar-Kołelis, D.; Wendt, J.A. Comparison of Cross-border Shopping Tourism Activities at the Polish and Romanian External Borders of European Union. Geogr. Pol. 2018, 91, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramsey, D.; Thimm, T.; Hehn, L. Cross-border Shopping Tourism: A Switzerland–Germany Case Study. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2019, 9, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drzewiecki, M. Podstawy Agroturystyki (The Basics of Agritourism); Oficyna Wydawnicza OPO: Bydgoszcz, Poland, 2001. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szwichtenberg, A. Turystyka Alternatywna i Ekoturystyka—Nowe Pojęcia w Geografii Turyzmu (Alternative Tourism and Ecotourism—New Concepts in the Geography of Tourism. Turyzm 1993, 3, 51–59. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzieniecki, T. Destynacje Transgraniczne w Europie—Identyfikacja, Klasyfikacja i Perspektywy Rozwoju (Cross-border Destinations in Europe—Identification, Classification and Development Perspectives). In Wymiana Doświadczeń i Dobrych Praktyk we Współpracy Transgranicznej (Echange of Experiences and Good Practises in Cross-Border Cooperation; Dąbrowski, D., Zbucki, Ł., Eds.; Państwowa Szkoła Wyższa im. Papieża Jana Pawła II: Biała Podlaska, Poland, 2020; pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, P. Polska i Jej Granice. Z Historii Polskiej Geografii Politycznej (Poland and Its Borders. From the History of Polish Political Geography; Wydawnictwo UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2004. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyński, M. Zmienność Funkcji Granic Międzynarodowych na Ziemiach Polskich od Czasów Rzeczypospolitej Szlacheckiej do Przystąpienia Polski do Układu z Schengen (Changeability of the International Borders Functions on Polish Territories from the Times of the Commonwealth (Poland & Lithuania) until Accession of Poland to the Schengen Agreement). In Problematyka Geopolityczna Ziem Polskich (Geopolitical Problems of Polish Territories); Eberhardt, P., Ed.; Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kennard, A. Old Cultures, New Institutions. Around the New Eastern Border of the Europe; LIT: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kondracki, J. Geografia Regionalna Polski (Regional Geography of Poland); Polskie Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warsaw, Poland, 1998. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Krukowska, R. Pojezierze Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie—Funkcja Turystyczna Regionu (Łęczna-Włodawa Lakeland—Tourist Function of the Region. Folia Tur. 2009, 21, 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak, A.; Dmytruk, H.; Sokół, J.L.; Dąbrowski, D. Wizerunek Pojezierza Szackiego w Percepcji Ukraińskich Turystów (The Image of Shatsk Lakeland in the Perception of Ukrainian Tourists. In Obszary Przyrodniczo Cenne w Rozwoju Turystyki (Naturally Valuable Areas in the Development of Tourism); Jalinik, M., Bakier, S., Eds.; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej: Białystok, Poland, 2020; pp. 245–259. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temereva, O.P. Рекреационно-туристический Потенциал 3аказника «Прибужское Полесье» (The Recreational and Tourist Potential of the Pribuzhskoye Polesie Biosphere Reserve). In Устойчивое развитие: региональные аспекты: сборник материалов Международной научно-практической конференции молодых ученых в рамках года науки в Республике Беларусь (Sustainable Development: Regional Aspects: Material of the International Scientific and Practical Conference of Young Scientist with the Framework of the Year of Science in the Republic of Belarus); Volchek, A.A., Ed.; Ministry of Education of the Republic of Belarus, Brest State Technical University, Brest State University: Brest, Belarus, 2017; pp. 558–561. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Miszczuk, A. Uwarunkowania Rozwoju Turystyki Aktywnej na Obszarach Wiejskich w Polsko-białorusko-ukraińskim Regionie Transgranicznym (Condions for Development of Active Tourism in Rural Areas in the Polish-Belorusian-Ukrainian Cross-border Region). Studia KPZK PAN 2015, CLXVI, 9–27. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Biernat, S. Rola Granicy Państwowej w Przemianach Krajobrazowych Doliny Bugu (The Role of the State Border in the Landscape Changes of the Bug Valley). Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kulturowego. Gran. W Kraj. Kult. 2006, V, 173–182. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Statistics Poland). Available online: www.stat.gov.pl/BDL/podrupy/tablica (accessed on 18 August 2021). (In Polish)

- Брестский районный исполнительный комитет (Brest District Executive Committee). Available online: www.brest.brest-region.gov.by (accessed on 18 August 2021). (In Russian)

- Державна Cлужба Cтатистики України (State Statistics Service of Ukraine). Available online: www.ukrstat.gov.ua (accessed on 18 August 2021). (In Ukraininan)

- Bronisz, U.; Jakubowski, A. Społeczno-gospodarcze Uwarunkowania Rozwoju Przedsiębiorczości na Obszarze Polesia Zachodniego (Powiat Łęczyński i Włodawski) (Socio-economic Determinants of Entrepreneurship Development in the Araea of Western Polesie (Poviats Łęczyński and Włodawski). In Potencjał Polesia Lubelskiego a Zrównoważony Rozwój Transgranicznego Rezerwatu Biosfery Polesie Zachodnie (Potential of Polesie Lubelskie and the Sustainable Development of the Cross-border Biosphere Reserve Western Polesie); Dobrowolski, R., Mięsiak-Wójcik, K., Demczuk, P., Eds.; Starostwo Powiatowe w Łęcznej: Łęczna, Poland, 2015; pp. 69–81. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Anisiewicz, R. Z Przeszłości i Teraźniejszości Linii Kolejowej Brześć–Włodawa (From the Past and Present of Brest–Włodawa Railway Line). Wschód. Kwart. -Społeczno-Kult. 2021, 1, 20–25. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Anisiewicz, R. Tourists Assets of the Cross-border Railway Line Brest–Chełm. Pr. Kom. Geogr. Komun. PTG 2020, 23, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, J.A.; Pashkov, S.V.; Mydłowska, E.; Bógdał-Brzezińska, A. Political and Historical Determinants of the Differentiation of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems of Agritourism in Poland and Kazakhstan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wschodni Szlak Rowerowy Green Velo (East of Poland Cycling Trail Green Velo). Available online: https://greenvelo.pl (accessed on 22 August 2021).

- Muzeum—Zespół Synagogalny We Włodawie (Museum—Synagogue Complex in Włodawa). Available online: www.muzeumwlodawa.pl (accessed on 4 September 2021). (In Polish)

- Muzeum i Miejsce Pamięci w Sobiborze (Museum and Memory Site in Sobibór). Available online: www.sobibor-memorial.eu (accessed on 4 September 2021). (In Polish)

- Stowarzyszenie—Lokalna Grupa Działania “Poleska Dolina Bugu” (Association—The Local Action Group “Poleska Dolina Bugu”). Available online: Dolina-bugu.pl (accessed on 9 September 2021). (In Polish)

- Debbage, K. Geographies of Tourism Entrepreneurship and Innovation: Evolving ResearchAagenda. In A Research Agenda for Tourism Geography; Müller, D.K., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Cities: Establishing the Framework Conditions. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 42, 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, T.G.; Teixeira, N.; Lisboa, I. Perceptions of Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism Sector: A Study in Municipality of Setúbal. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Internationalization; Teixeira, N.M., da Costa, T.G., Lisboa, I.M., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, C.; Duffy, L.; Clark, D. Fostering Tourism and Entrepreneurship in Fringe Communities: Unpacking Stakeholder Perceptions Towards Entrepreneurial Climate. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Administrative Units | Total Population | Cities/Towns | Villages | % In Cities/Towns | Population per 1 km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland—municipalities in total | 25,546 | 12,915 | 12,631 | 50.6% | 46 |

| The city of Włodawa | 12,915 | 12,915 | 0 | 719 | |

| Hanna | 2791 | 0 | 2791 | 20 | |

| The village of Włodawa | 6023 | 0 | 6023 | 25 | |

| Wola Uhruska | 3817 | 0 | 3817 | 25 | |

| Belarus—selsoviets in total | 10,291 | 1247 | 9044 | 12.1% | 17 |

| Znamienka | 5280 | 0 | 15 | ||

| Domachevo | 2686 | 1247 | 1439 | 17 | |

| Tomashovka | 2325 | 0 | 2325 | 23 | |

| Ukraine—Shatsk district | 16,634 | 5270 | 11,364 | 31.7% | 22 |

| Administrative Units | Total Population | Pre-Working Age | Working Age | Post-Working Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipalities in total | 25,546 | 17.1% | 59.1% | 23.8% |

| Włodawa City | 12,915 | 17.3% | 57.3% | 25.4% |

| Hanna | 2791 | 14.9% | 61.3% | 23.8% |

| Rural Włodawa | 6023 | 19.1% | 60.4% | 20.5% |

| Wola Uhruska | 3817 | 14.8% | 61.9% | 23.3% |

| Project Name | Beneficiary | Value in PLN | EU Co-Financing in PLN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regional Operational Programme of Lublin Voivodeship for the years 2007–2013 | |||

| Improvement of tourist accessibility of Włodawa—the city of three borders and three cultures | Urban municipality of Włodawa | 2,362,060.55 | 1,650,575.04 |

| Promotional programme for cultural and tourist values of Włodawa—the city of three borders and three cultures | Urban municipality of Włodawa | 1,976,619.94 | 1,382,774.96 |

| Tourist and recreational management of Włodawa Municipality | Rural municipality of Włodawa | 1,949,088.14 | 1,364,361.69 |

| The Bug River Valley—Endless Possibilities | Wola Uhruska Municipality | 3,737,362.80 | 2,512,897.95 |

| Improvement of tourist accessibility of St. Louis Church in Włodawa situated at the Three Cultures Route | St. Louis Roman Catholic Church Parish | 3,672,469.39 | 2,569,036.38 |

| Improvement of communication in the ancient centre of Włodawa—the City of Three Cultures | Urban municipality of Włodawa | 4,013,769.03 | 1,635,894.36 |

| Regional Operational Programme of Lublin Voivodeship for the years 2014–2020 | |||

| The Bug River wooden architecture monuments in Hanna municipality | Hanna Municipality | 8,345,608.35 | 5,562,639.94 |

| Revitalisation of Włodawa | Urban municipality of Włodawa | 18,487,807.40 | 12,796,834.88 |

| Renovation of ancient Orthodox Churches in Uhrusk, Chełm and Dubienka | Orthodox Church parish in Chełm | 7,082,023.25 | 5,420,326.03 |

| Increasing accessibility of the ancient synagogue complex in Włodawa | Synagogue Museum Complex | 4,972,571.26 | 3,419,130.17 |

| Modernisation of the ancient synagogue complex in Włodawa—Great and Small Synagogue | Synagogue Museum Complex | 3,998,621.60 | 2,768,043.37 |

| Eastern cultural heritage of Łęczyńsko-Włodawskie Lakeland: revitalisation of ancient Orthodox Churches in Włodawa and Sosnowica | Orthodox Church parish in Włodawa | 3,972,078.29 | 2,583,109.33 |

| Modernization of the ancient Synagogue Complex in Włodawa—Kahal Home and green areas | Synagogue Museum Complex | 1,450,225.24 | 1,010,135.32 |

| Włodawa Tourist Route—the Bug River Promenade | Urban municipality of Włodawa | 1,253,319.99 | 744,054.06 |

| Years | Municipal Facilities in Total | Okuninka | Orchówek | Sobibór | Szuminka | Suszno | Żłobek | Korolówka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| 2001 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| 2002 | - | |||||||

| 2003 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| 2004 | 11 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| 2005 | 8 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| 2006 | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| 2007 | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| 2008 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2009 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| 2010 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2011 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2012 | 11 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| 2013 | 5 | 4 | 1 | |||||

| 2014 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2015 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2016 | - | |||||||

| 2017 | - | |||||||

| 2018 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| 2019 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anisiewicz, R. Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413595

Anisiewicz R. Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413595

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnisiewicz, Renata. 2021. "Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413595

APA StyleAnisiewicz, R. (2021). Conditions for Development of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Tourism in the Border Area of the European Union: The Example of the Tri-Border Area of Poland–Belarus–Ukraine. Sustainability, 13(24), 13595. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413595