Evolution of Short Food Supply Chain Innovation Niches and Its Anchoring to the Socio-Technical Regime: The Case of Direct Selling through Collective Action in North-West Portugal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

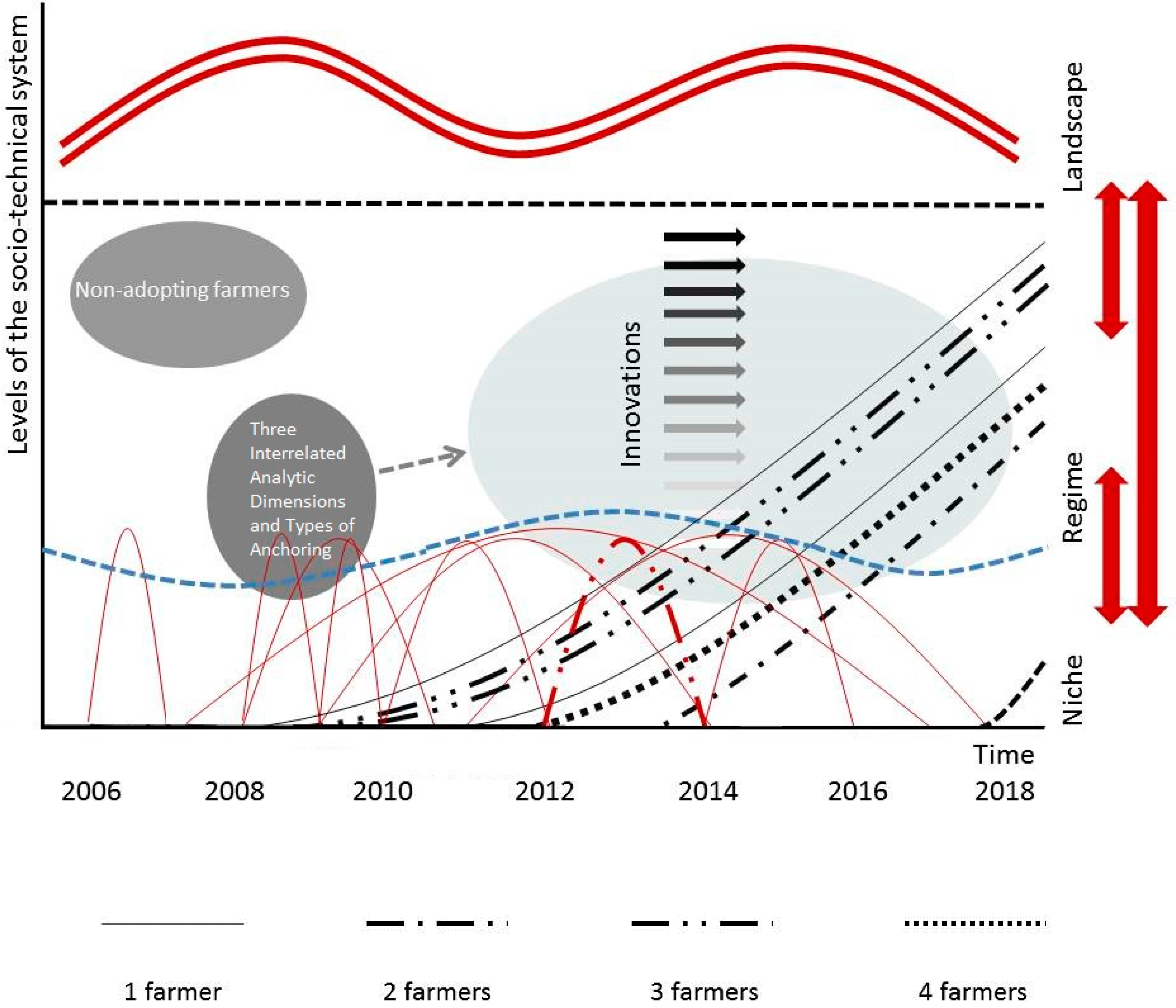

2. Theoretical Approach

2.1. From Transition Theory to Anchoring

2.2. Basket in Direct Selling as Short Food Supply Chains (SFSC)

3. Materials and Methods

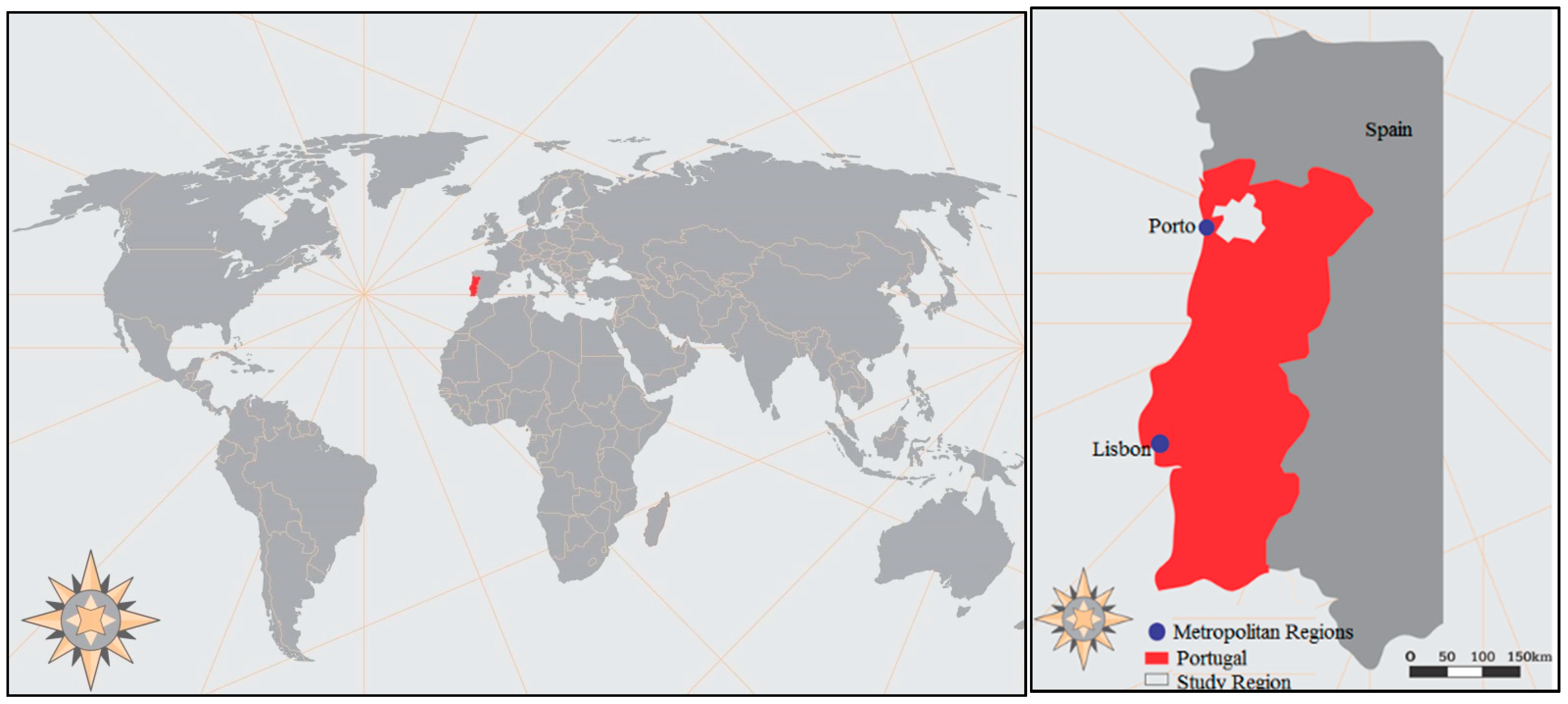

3.1. Presentation of the Region under Study and Characterisation of the Novelty

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Implementing Innovation

4.2. Distinguishing between Pathways

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rip, A.; Kemp, R. Towards a theory of sociotechnical change. In Human Choice and Climate Change; Rayner, S., Majone, E.L., Eds.; Battelle Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 1998; pp. 327–399. [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, F.; Smith, A.; Stirling, A. Socio-technical regimes and transition contexts. In System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability; Elzen, B., Geels, F., Green, K., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2004; pp. 48–75. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Demartini, E.; Gaviglio, A.; Pirani, A. Farmers’ motivation and perceived effects of participating in short food supply chains: Evidence from a North Italian survey. Agric. Econ. 2017, 63, 204–216. [Google Scholar]

- GPP—Gabinete de Planeamento, Políticas e Administração Geral. Available online: http://www.gpp.pt/images/Agricultura/Estatisticas_e_Analises/Estatisticas/AnaliseEstruturaExplAgricolas2016.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Madureira, L.; Mucha, T.; Barros, A.B.; Marques, C. The Role of Advisory Services in Farmers’ Decision Making for Innovation Uptake. Insights from Case Studies in Portugal; UTAD: Vila Real, Portugal, 2019; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Translating Sustainabilities between Green Niches and Socio-Technical Regimes. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2007, 19, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzen, B.; van Mierlo, B.; Leeuwis, C. Anchoring of innovations: Assessing Dutch efforts to harvest energy from glasshouses. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2012, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, S.; Cardona, A.; Lamine, C.; Cerf, M. Sustainability transitions: Insights on processes of niche-regime interaction and regime reconfiguration in agri-food systems. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 48, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slingerland, M.; Schut, M. Jatropha Developments in Mozambique: Analysis of Structural Conditions Influencing Niche-Regime Interactions. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7541–7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geels, F. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H. The Multi-Level Perspective in Research on Sustainability Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2019, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hinrichs, C.C. Transitions to sustainability: A change in thinking about food systems change? Agric. Human. Values 2004, 31, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J. Ordering theories: Typologies and conceptual frameworks for sociotechnical change. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2017, 47, 703–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R.; van Asselt, M.; Geels, F.; Verbong, G.; Molendijk, K. Transities en Transitiemenagement: De Casus van een Emissiearme Energievoorziening; ICIS/MERIT: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–123. [Google Scholar]

- López-García, D.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Di Masso, M.; Espluga, J. Multi-actor networks and innovation niches: University training for local Agroecological Dynamization. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 36, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; Gazolla, M.; de Carvalho, C.X.; Schneider, S. A produção de novidades: Como os agricultores fazem para fazer diferente? In Os Atores do Desenvolvimento Rural: Perspectivas Teóricas e Práticas Sociais; Schneider, S., Gazolla, M., Eds.; Editora da UFRGS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2011; pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Konefal, J. Governing Sustainability Transitions: Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives and Regime Change in United States Agriculture. Sustainability 2015, 7, 612–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roep, D.; Van Der Ploeg, J.; Wiskerke, J. Managing technical-institutional design processes: Some strategic lessons from environmental co-operatives in the Netherlands. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2003, 51, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wigboldus, S.; Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C.; Schut, M.; Muilerman, S.; Jochemsen, H. Systemic perspectives on scaling agricultural innovations: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seoane, M.V.; Marín, A. Transiciones hacia una agricultura sostenible: El nicho de la apicultura orgánica en una cooperativa Argentina. Mundo Agrar. 2017, 18, e049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hargreaves, T.; Longhurst, N.; Seyfang, G. Up, down, round and round: Connecting regimes and practices in innovation for sustainability. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 402–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loeber, A. Inbreken in Het Gangbare Transitie-Management in de Praktijk: De NIDO-Benadering; NIDO: Leeuwarden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F. The dynamics of transitions in socio-technical systems: A multi-level analysis of the transition pathway from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles (1860–1930). Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2005, 17, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Major system change through stepwise reconfiguration: A multi-level analysis of the transformation of American factory production (1850–1930). Technol. Soc. 2006, 28, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J. Framing niche-regime linkage as adaptation: An analysis of learning and innovation networks for sustainable agriculture across Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Maye, D.; Kirwan, J.; Curry, N.; Kubinakova, K. Interactions between Niche and Regime: An Analysis of Learning and Innovation Networks for Sustainable Agriculture across Europe. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2015, 21, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Darnhofer, I.; Darrot, C.; Beuret, J.E. Green tides in Brittany: What can we learn about niche–regime in-teractions? Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2013, 8, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.-A.; Peter, S.; Zagata, L. Conceptualising multi-regime interactions: The role of the agriculture sector in renewable energy transitions. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 1543–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vankeerberghen, A.; Stassart, P.M. The transition to conservation agriculture: An insularization process towards sustainability. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2016, 14, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmin, R.; Meynard, J.M.; Julhia, L.; Casabianca, F. Sociotechnical controversies as warning signs for niche governance. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schiller, K.; Godek, W.; Klerkx, L.; Poortvliet, P.M. Nicaragua’s agroecological transition: Transformation or recon-figuration of the agri-food regime? Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 44, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, B.; Stankiewicz, R. On the nature, function and composition of technological systems. J. Evol. Econ. 1991, 1, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 1–178. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Stirling, A.; Berkhout, F. The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1491–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, A.; Cristóvão, A.; Rodrigo, I.; Tibério, L. Relatório Final de Avaliação do Projecto de Cooperação Interterritorial Prove–Promover e Vender. A Perspectiva dos Actores e Equipa de Trabalho; ISA-UTL e UTAD: Portugal, 2012; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ader—Sousa. Available online: https://www.adersousa.pt/iniciativas/prove/ (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Dolmen. Available online: https://www.dolmen.pt/ (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Balázs, B.; Trenchard, L.; Eyden-Wood, T.; Bos, E.; Sutton, G.; Blackett, M. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of Their Socio-Economic Characteristics; Joint Research Centre: Seville, Spain, 2013; pp. 1–128. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d16f6eb5-2baa-4ed7-9ea4-c6dee7080acc/language-en (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Renting, H.; Marsden, T.K.; Banks, J. Understanding Alternative Food Networks: Exploring the Role of Short Food Supply Chains in Rural Development. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Todorovic, V.; Maslaric, M.; Bojic, S.; Jokic, M.; Mircetic, D.; Nikolicic, S. Solutions for More Sustainable Distribution in the Short Food Supply Chains. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, P.; Pekkanen, P. Estimating the business potential for operators in a local food supply chain. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2815–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Wang, M.; Kumari, A.; Akkaranggoon, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Neutzling, D.; Tupa, J. Exploring short food supply chains from Triple Bottom Line lens: A comprehensive systematic review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Bangkok, Bangkok, Thailand, 5–7 March 2019; pp. 728–738. Available online: http://ieomsociety.org/ieom2019/papers/216.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Bellec-Gauche, A.; Chiffoleau, Y.; Maffezzoli, C. Glamur Project Multidimensional Comparison of Local and Global Fresh Tomato Supply Chains; INRA: Montpellier, France, 2015; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ogier, M.; Cung, V.-D.; Boissière, J. Design of a Short and Local Fresh Food Supply Chain: A Case Study in Isère. In International Workshop on Green Supply Chain (GSC). In Proceedings of the ROADEF-15ème Congrès Annuel de la Société Française de Recherche Ppérationnelle et d’aide à la Decision, Arras, France, 26–28 February 2014; pp. 1–11. Available online: https://hal.univ-smb.fr/hal-01009391/ (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Majewski, E.; Wąs, A.; Borgen, S.O.; Csillag, P.; Donati, M.; Freeman, R.; Hoàng, V.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Mancini, M.C.; et al. Measuring the Economic, Environmental, and Social Sustainability of Short Food Supply Chains. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P.; De Labarre, M.D.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Maj, A.; Majewski, E.; et al. Short Food Supply Chains and Their Contributions to Sustainability: Participants’ Views and Perceptions from 12 European Cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, R. Social innovation as a collaborative concept. Innov.-Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 30, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, L.C.S.; Rodrigues, E.M.; Pinto-Ferreira, J.J. Supporting Collaborative Innovation Networks for New Concept Development through Web Mashups. In Risks and Resilience of Collaborative Networks; Camarinha-Matos, L., Bé-naben, F., Picard, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lundvall, B.-Å.; Borrás, S. Science, Technology and Innovation Policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation; Fagerberg, J., Mowery, D.C., Richard, R.N., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 599–631. [Google Scholar]

- Zurbriggen, C.; Sierra, M. Innovación colaborativa: El caso del Sistema Nacional de Información Ganadera. Agrociencia Urug. 2017, 21, 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–526. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project H2020 AgriLink. Available online: https://www.agrilink2020.eu/ (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições 70: Lisbon, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, A.; Cristóvão, A.; Rodrigo, I.; Tibério, M.L. Parcerias, acção coletiva e desenvolvimento de sistemas alimentares localizados: O projecto Prove em Portugal. Perspect. Rural. Nueva Época 2014, 23, 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities. 2009. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/oslo-manual_9789264013100-en (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- OECD and Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data; OECD: Paris, France, 2005; pp. 1–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbiose. Available online: https://www.simbiose.com.pt/fat-portfolio/prove-o-projeto-que-permite-provar-localmente/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Wolfe, D.A.; Gertler, M.S. Innovation and Social Learning: An Introduction. In Innovation and Social Learning: Institutional Adaptation in an Era of Technological Change, 2nd ed.; Gertler, M.S., Wolfe, D.A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2002; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hultine, S.; Cooperband, L.; Curry, M.; Gasteyer, S. Linking Small Farms to Rural Communities with Local Food: A Case Study of the Local Food Project in Fairbury, Illinois. Community Dev. 2007, 38, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudisca, S.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Sgroi, F.; Testa, R. Socio-economic assessment of direct sales in Sicilian farms. Ital. J. Food. Sci. 2015, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| Reference | Contribution to Studies on Anchoring |

|---|---|

| Elzen, van Mierlo and Leeuwis (2012) [9] | This study suggests anchoring is an analytical concept to explain the continuous process of establishing and breaking relations between niches and regimes and among niches. |

| Diaz, Darnhofer, Darrot and Beuret (2013) [30] | This study emphasises the social role of transitions, highlighting that neither niches nor regimes are static entities; on the contrary, they act and react with and to each other. It suggests anchoring is not a sequential process but a continuous and recurrent one. |

| Slingerland and Schut (2014) [22] | This study shows niche-regime interactions need efficient conditions if they are to be implemented. |

| Ingram (2015) [28] | This study deals with anchoring as an adaptive process, whereby niches and regimes adapt to each other as a result of reflexive and learning processes on the part of the actors involved. |

| Ingram, Maye, Kirwan, Curry and Kubinakova (2015) [29] | This study suggests transition to sustainable agriculture may be looked at as interactive and adaptive complex changes rather than a regime shift. |

| Sutherland, Peter and Zagata (2015) [31] | This study addresses multiple regimes of renewable energy production by the agricultural sector, suggesting the emergence of a new regime out of the political role of this type of process. |

| Bui, Cardona, Lamine and Cerf (2016) [10] | This study identifies common anchoring phases or patterns in four studies regarding agency and governance factors. |

| Vankeerberghen and Stassart (2016) [32] | This study develops the concept of insularisation to characterise the process whereby a niche develops within a regime and gradually and steadily detaches from it. |

| Belmin, Meynard, Julhia and Casabianca (2018) [33] | This study does not explain what an anchoring process is, but it gives an example of a relation between niche and regime in which innovations are not necessarily aligned with the niche, but are a subsystem of the regime. This perception even suggests new transition concepts. |

| López-García, Calvet-Mir, Di Masso, and Espluga (2019) [17] | This study stresses the importance of creating hybrid forums that may become interaction loci between niche actors and regimes. Through these forums, innovations could overcome the regime by linking themselves to different types of actors. |

| Schiller, Godek, Klerkx and Poortvliet (2020) [34] | This study creates a time line to explain the development of a specific niche: the agroecological niche. The conclusion is that the agroecology did not necessarily create a transition but was incorporated into the regime. |

| Three Interrelated Analytic Dimensions | 1. Socio-technical systems: involve actor networks gathered around a specific institutional structure to disseminate a technology; they also include knowledge flows or skills required by the technology [35]. |

| 2. Rules and institutions: refer to normative, cognitive, and regulatory aspects [36] of how innovations emerge. | |

| 3. Human actors, organisations, and social groups: may refer to enterprises that create technologies, or political actors who legislate it, or the users of a novelty [12]. | |

| Types of Anchoring | 1. Technological: concerns technological innovations when actors define the technical features of the novelty [9]. |

| 2. Institutional: represents the universe of rules (cognitive, interpretative normative, and economic) mobilised, adapted, or created to support innovations [9]. | |

| 3. Network-related: means a shift in the relationship between actors (contacts, exchanges, interdependencies, and coalitions) that change as a novelty develops [9]. |

| Relation to the Novelty and Coding | Period | Age Group (Years) | University Degree | Main Crops | Complementary Innovations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supporters | 01 | Since 2012 | 51–60 | No university degree | Fruit, vegetables, and small animals | Introduction of new crops Selling animal products |

| 02 | Since 2018 | 31–40 | University degree | Berries | Introduction of new crops Fruits and vegetables processing Marketing differentiation | |

| 03 | Since 2012 | 61–70 | University degree | Fruits and vegetables | Introduction of new crops Developing tourism activities | |

| 04 | Since 2013 | 31–40 | University degree | Vegetables, and ”gourmet market products” | Selling to gourmet restaurants and markets Developing new tools or technologies aimed at improving productivity | |

| 05 | Since 2010 | 31–40 | No university degree | Mushrooms | Teaching farmers to work with a new crop | |

| 06 | Since 2013 | 31–40 | No university degree | Beef cattle, grapevines, and vegetables | Introduction of new crops | |

| 07 | Since 2011 | 51–60 | No university degree | Fruits and vegetables | Introduction of new crops | |

| 08 | Since 2009 | 41–50 | No university degree | Beef cattle, grapevines, and vegetables | Introduction of new crops | |

| 09 | Since 2008 | 51–60 | University degree | Fruits, vegetables, and asparagus | Introduction of new crops | |

| 10 | Since 2009 | 31–40 | No university degree | Grapevines, berries and kiwis | Introduction of new crops | |

| 11 * | Since 2010 | 31–40 | No university degree | Vegetables, grapevines, and beef cattle | Opening a own store | |

| 12 * | Since 2010 | 31–40 | University degree | Berries | Introduction of new crops Selling to gourmet restaurants and markets | |

| 13 * | Since 2012 | 31–40 | No university degree | Fruits and vegetables | Developing tourism activities Fruits and vegetables processing | |

| 14 * | Since 2009 | 51–60 | University degree | Fruits and vegetables | Innovating in management | |

| 15 * | Since 2012 | 51–60 | University degree | Fruits and vegetables | Introduction of new crops | |

| Limitations of basket direct selling pointed out by farmers who gave it up (more descriptions in Table 4) | ||||||

| Have given it up | 16 | 2012–2014 | 51–60 | University degree | Fruits and vegetables | Insufficient production and buyers |

| 17 | 2012–2014 | 21–30 | University degree | Grapevines, kiwis, and mushrooms | Specialised productions Group dynamics, management, and leadership | |

| 18 | 2010–2012 | 61–70 | No university degree | Fruits, vegetables, aromatic and medicinal herbs | Group dynamics, management, and leadership | |

| 19 | 2014–2016 | 51–60 | University degree | Aromatic herbs | Specialised productions Group dynamics, management, and leadership | |

| 20 | 2012–2014 | 41–50 | No university degree | Vegetables | Group dynamics, management, and leadership | |

| 21 | 2007–2017 | 41–50 | No university degree | Chestnuts | Specialised productions Lack of profit | |

| 22 | 2011–2018 | 41–50 | No university degree | Chickens for rearing, and vegetables | Group dynamics, management, and leadership Insufficient production and buyers Lack of profit | |

| 23 | 2008–2009 | 41–50 | No university degree | Aromatic herbs | Specialised productions | |

| 24 | 2008–2011 | 41–50 | No university degree | Vegetables | Group dynamics, management, and leadership Lack of profit | |

| 25 | 2006–2007 | 61–70 | No university degree | Vegetables | Lack of profit | |

| 26 | 2009–2014 | 41–50 | No university degree | Vegetables | Group dynamics, management, and leadership Lack of profit | |

| 27 | 2009–2010 | 41–50 | No university degree | Vegetables, kiwis and grapevines (hereafter “vines”) | Lack of profit | |

| Reasons why farmers never wanted to join the innovation | ||||||

| Non-supporters | 28 | Does not apply | 61–70 | University degree | Vines whose production is sold to a cooperative | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperatives and age of the farmer |

| 29 | Does not apply | 41–50 | No university degree | Vines whose production is sold to a cooperative | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperatives | |

| 30 | Does not apply | 41–50 | No university degree | Vines whose production is sold to a cooperative | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperatives | |

| 31 | Does not apply | 51–60 | No university degree | Vines whose production is sold to a cooperative, and flowers sold to middlemen | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperative Age of the farmer | |

| 32 | Does not apply | 51–60 | No university degree | Kiwis, and vines whose production is sold to a cooperative | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperative Age of the farmer | |

| 33 | Does not apply | 71–80 | No university degree | Vines whose production is sold to a cooperative | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperative Age of the farmer | |

| 34 | Does not apply | 71–80 | No university degree | Vines whose production is sold to a cooperative | Guaranteed sale to wine cooperatives Age of the farmer | |

| Limitations | Description | Narrative Extract |

|---|---|---|

| Specialised productions | The baskets included a few aromatic herbs and mushrooms. Namely mushrooms were delivered in small quantities although they represented a high percentage of the basket’s final cost. | “In the case of Prove, I only produced mushrooms. I mean, it’s one thing to add a product that, at the time, cost five Euros per kilo, but quite another to add one kilo apples which cost sixty cents […] If we look at the percentage, in a ten to fifteen Euro basket, […] for me it was already ten percent, I get it. I get it that I was delivering a product which cost ten percent of the final price, which is a lot, I know…” (Interview 18). “In my case, direct selling didn’t mean much after all, and it didn’t feel right, either; since I only contributed with a very small amount, because I was only supplying aromatic herbs, I wasn’t very interested.” (Interview 20). |

| Insufficient production and buyers | Basket inadequacy for customer food and gastronomic preferences and demand, and customer failure to become regular buyers. Additionally, competition from similar products from other suppliers such as fairs and supermarkets. | “But then, after a while, there are disadvantages to that basket-buying thing because it becomes a routine, and after some time people are tired; they like to change, every now and then. In fact, after two or three years, they begin to be a little fed-up.” (Interview 23). “Baskets are fewer because of the competition. Right now, many firms that have nothing to do with Prove are increasing the supply of vegetables and advertise biologic vegetables that are not biologic at all, but that they claim they are. So, this is a terrible mess.” (Interview 19). |

| Group dynamics, management, and leadership | Disagreement, among participants, as to the program’s underlying philosophies of supplying only seasonal products, and concentration of basket delivery in the hands of a few participants (who began acting as product brokers); Lack of time and preparation on the part of the farmers to deal in commercial activities, for instance not knowing how to handle customer complaints and demands; Lack of leadership that might have taken over the project after LDAs were no longer responsible for it; Lower acceptance of baskets in rural areas due to residents having, in some other way, access to fresh, organic, and seasonal products; Farmer difficulty transporting the baskets from production sites to distribution areas due to a lack of appropriate vehicles. | “There must be trust between the people who supply the baskets […] sometimes that is a limitation because, deep down, we are responsible for the food security of a basket that is not only ours, and that may have its implications.” (Interview 20). “In the middle of all that, one or another producer would buy bananas and add them to the basket. Ok, let’s not say bananas but goods… Personally, I think that if I don’t have the goods, it’s no use inviting me because I am not going to invent them, but that is not how it goes with some people, they don’t mind going to the market to buy or sell, but that doesn’t work with me. People have to understand that if you don’t have the product, you just don’t; if you cannot supply the basket this week, you can’t. “(Interview 21). “But there is always a producer who has the most responsibility, who monopolises and manages the group. As it happened with Prove, in the end, they decided what to add to the basket. And then, there is the greed.” (Interview 17). “Here, in Marco, the situation was different because it is a rural area, and most baskets were meant to Porto and Gaia. Ok, everybody has vegetables, everybody has a little of everything. Marco is a small town, and most baskets went to Porto, Vila Nova de Gaia, and that has costs. Nobody works for free; you have to pay for tolls, oil, and, at the end of the day, the business was not lucrative. “Interview 24). “[…] besides, everybody has an uncle, or a father-in-law who has a vegetable garden, so it is difficult to sell, unless, of course, you do something different […].” (Interview 22). “What was difficult for me was the distance, having a distribution point, and, at the same time, sustaining the project because I had to guarantee some income. I didn’t produce enough vegetables and had to rely on other colleagues and all that logistics to ensure we had quality goods, especially biological ones. So, it became more and more difficult. “(Interview 19). |

| Profit limitations | The small amounts that were delivered, besides the time farmers spent assembling the baskets made the activity less lucrative and the programme less attractive. | “It’s just that everything is very fussy, and one spends much time on the road to deliver the baskets; in my case, I had no time to grow the goods. Perhaps there should be teams to deal with one thing and the other. Also, there were no clients. Let’s say, perhaps, that the highest number of baskets I ever delivered was fifteen, seventeen, but mostly we did it as a favour, you know, to help out. And then, we were delivering seven, eight baskets, which is complicated. Five farmers delivered eight baskets …” (Interview 21). “As you know, the programme rests on delivering baskets, but the number of baskets I expected to need was small; therefore it was not worth my selling directly half a dozen kilos lettuce, half a dozen kilos tangerines or tomatoes… (Interview 25). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polita, F.S.; Madureira, L. Evolution of Short Food Supply Chain Innovation Niches and Its Anchoring to the Socio-Technical Regime: The Case of Direct Selling through Collective Action in North-West Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413598

Polita FS, Madureira L. Evolution of Short Food Supply Chain Innovation Niches and Its Anchoring to the Socio-Technical Regime: The Case of Direct Selling through Collective Action in North-West Portugal. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413598

Chicago/Turabian StylePolita, Fabíola Sostmeyer, and Lívia Madureira. 2021. "Evolution of Short Food Supply Chain Innovation Niches and Its Anchoring to the Socio-Technical Regime: The Case of Direct Selling through Collective Action in North-West Portugal" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413598

APA StylePolita, F. S., & Madureira, L. (2021). Evolution of Short Food Supply Chain Innovation Niches and Its Anchoring to the Socio-Technical Regime: The Case of Direct Selling through Collective Action in North-West Portugal. Sustainability, 13(24), 13598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413598