Effect of Chief Executive Officer’s Sustainable Leadership Styles on Organization Members’ Psychological Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

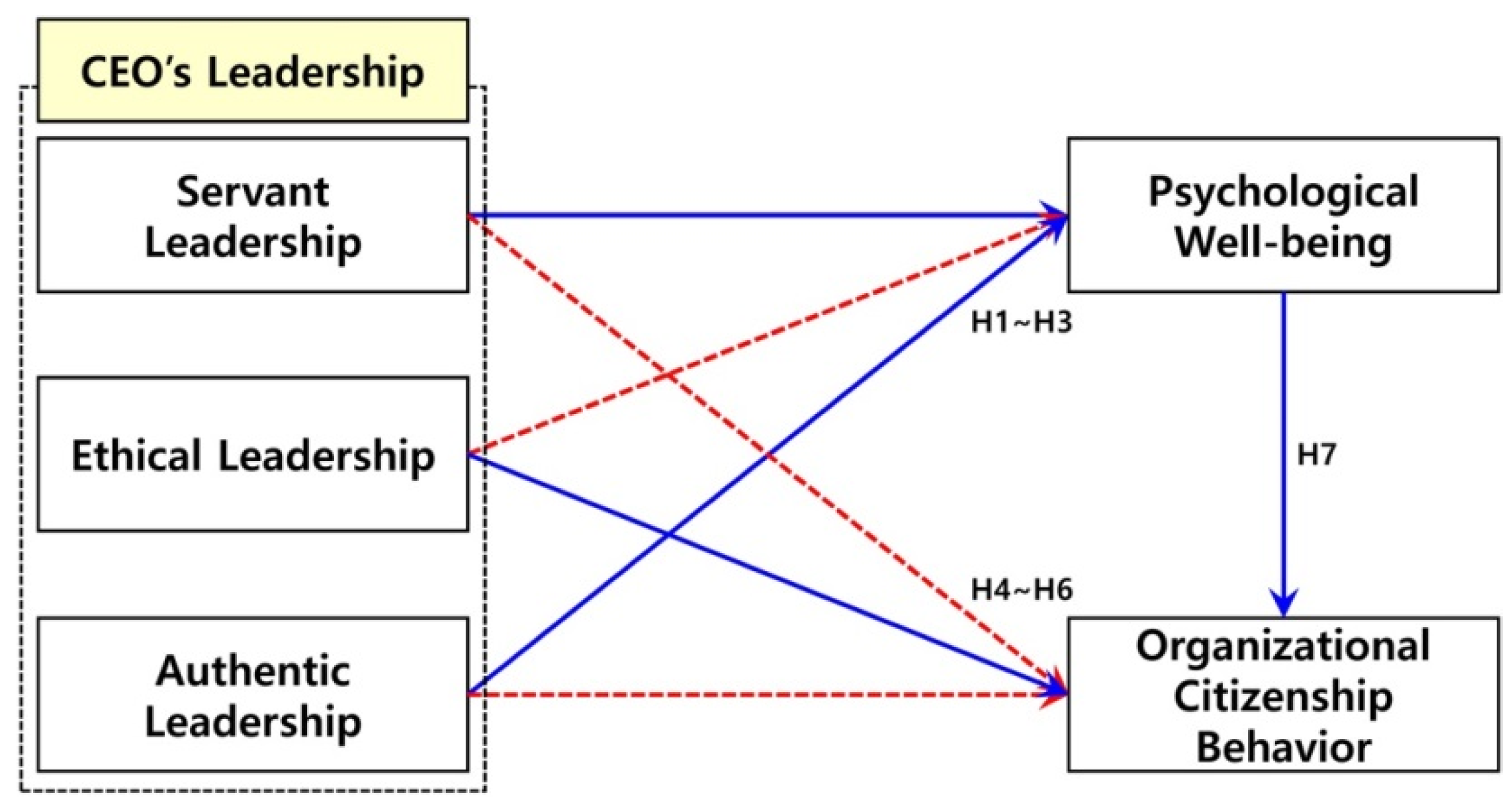

- Research Question 1. What are the effects of the CEO’s sustainable leadership styles (servant, ethical, and authentic leadership) on the psychological well-being of organization members?

- Research Question 2. What are the effects of the CEO’s sustainable leadership styles (servant, ethical, and authentic leadership) on the organizational citizenship behavior of organization members?

- Research Question 3. What are the effects of the psychological well-being of organization members on organizational citizenship behavior?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Base Theory

2.1.1. Situational Theory

Situational Leadership Theory

Contingency Approach of Leadership

2.1.2. Bottom-Up Spillover Theory

2.1.3. Theories of Prosocial Behavior

2.2. Sustainable Leadership Styles

2.3. Servant Leadership

2.4. Ethical Leadership

- Honesty: a leader’s dishonest behavior in the form of lying or distorting reality creates an atmosphere of mistrust wherein organization members cannot trust the leader and thus lose faith.

- Justice: ethical leaders believe in justice and fairness. They prioritize treating every employee equally and place justice and fairness at the center of their decision making. They follow rules and do not give special treatment to any individual, except in special circumstances.

- Respect: leaders should listen carefully to others and confirm their inherent values. They should mentor others to become aware of their own purpose, values, and needs so that ethical qualities prevail throughout the organization. Furthermore, they always respect employees ethically, legally, and normatively [142,143].

- Community: ethical leaders behave altruistically, placing the welfare of their organization members in high esteem, and engage in activities such as team building, mentoring, and empowerment behaviors. This implies that they help to build a community and consider the value of the employees’ goals and the goals of the whole organization.

- Integrity: Ethical leaders demonstrate appropriate values to people around them through their own behavior. Leaders who behave with integrity can strengthen their organization by hiring talented and ethical employees. People generally want to work with leaders who have integrity and are therefore more likely to be attracted to organizations wherein leaders act with honesty and integrity [142,143].

2.5. Authentic Leadership

- Self-awareness refers to how organization members perceive leadership and understand their own strengths, weaknesses, and motivations. The leader’s self-awareness is the most essential element in authentic leadership [147,152]. Self-awareness occurs when the leader is aware of their existence in the circumstances that they are put in. Furthermore, it is not an ultimate goal but a series of processes in which efforts are continuously made to understand the leader’s inherent talents, strengths, objectives, core values, beliefs, and desires. Self-awareness includes a basic understanding of the leader’s knowledge, experience, and capabilities [147,152].

- Ethics/morality refers to how the leader acts according to internalized moral standards and values, rather than based on external pressures such as colleagues, organizations, and society. In this regard, authentic leaders seriously consider moral issues and develop ethical capability, efficacy, courage, and resilience to perform ethical actions sincerely and continuously. In short, morality refers to the process of ethical and transparent decision-making [153,154,155].

- Transparency refers to making efforts to share information and minimize inappropriate emotions. It is related to increasing trust through the expression of actual thoughts and emotions. Transparency is opposed to simply pleasing organization members, obtaining rewards, or avoiding punishment. It refers to actions that follow the leader’s values, preferences, and needs [149,150].

- Balanced processing implies that the leader analyzes all the appropriate information objectively before making decisions. The leader performs balanced processing by collecting opinions in opposition to their own and sufficiently reviewing information and various opinions related to major decision making. Such balanced processing has positive effects on employees’ behaviors through positive modeling [146].

2.6. Psychological Well-Being

2.7. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

- Altruism: this occurs when an organization member voluntarily helps others without expecting anything in return. Examples of altruistic behavior include helping an overburdened coworker to finish early or helping a new employee adapt to the organization quickly [168].

- Sportsmanship: this refers to behaving fairly and not gossiping or spreading rumors when one is dissatisfied with or has complaints about the organization or other members. It also refers to making efforts to understand the positive aspects of a situation. This includes engaging in proactive behavior for trying to solve a problem by directly talking to the involved person instead of simply putting up with the matter of complaint [171].

- Courtesy: this refers to taking steps in advance to prevent sudden frustration with other members regarding one’s work or personal circumstances. This behavior involves contacting other members who may be affected by one’s decisions or actions to ask for their understanding in advance and coordinate disagreements [171,172].

- Civic Virtue: this refers to showing interest in and actively participating in various official and unofficial activities of the organization. It includes social activities and interpersonal relationships with other organization members through clubs and social gatherings within the organization, proactive activities, and making changes by suggesting improvements that may help in the development of the organization [173].

2.8. Relationship between Key Variables

2.8.1. CEO’s Leadership and Psychological Well-Being

2.8.2. CEO’s Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

2.8.3. Psychological Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

3. Methods

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurement of Variables

3.3. Settings of Respondents

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Test

- The effects of a CEOs’ sustainable leadership styles (servant, ethical, and authentic leadership) on organization members’ psychological well-being was examined. According to the analysis, CEOs’ servant (β = 0.173, t = 2.046, p < 0.05) and authentic leadership (β = 0.292, t = 3.399, p < 0.01) showed statistically significant positive (+) effects on the psychological well-being of organization members. However, ethical leadership did not. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 3 were supported, while Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

- The effects of CEOs’ sustainable leadership styles (servant, ethical, and authentic leadership) on organizational citizenship behavior among organization members was examined. According to the analysis, CEOs’ ethical leadership (β = 0.184, t = 2.039, p < 0.05) had statistically significant positive (+) effects on the organizational citizenship behavior among organization members. However, servant and authentic leadership did not. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported, while Hypotheses 4 and 6 were not supported.

- The effects of organization members’ psychological well-being on organizational citizenship behavior was examined. According to the analysis, organization members’ psychological well-being (β = 0.493, t = 10.403, p < 0.01) had statistically significant positive (+) effects on organizational citizenship behavior. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 was supported.

4.4. Mediated Effect Test

- Psychological well-being showed a mediating effect in the path of servant leadership → psychological well-being → organizational citizenship behavior.

- Psychological well-being did not show a mediated effect in the path of ethical leadership → psychological well-being → organizational citizenship behavior.

- Psychological well-being showed a mediating effect in the path of authentic leadership → psychological well-being → organizational citizenship behavior. In particular, psychological well-being showed a fully mediated effect.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of the Study

- CEOs’ servant and authentic leadership had statistically significant positive (+) effects on organization members’ psychological well-being. These results support the results of previous studies conducted by Coetzer et al. [38,39], Ilies et al. [58], Jensen and Luthans [179], and Rivkin et al. [174] and can be summarized as follows. First, in terms of servant leadership, the results imply that CEOs should endeavor to build empathy with organization members based on listening, communicating, and coordinating attitudes. Moreover, they mean that CEOs should show interest in solving the problems and discomforts faced by organization members and try to develop their capabilities. CEOs should always have a humble attitude and put forth efforts to work together based on persuasion rather than obedience. Furthermore, they should provide alternatives through clear awareness and present visions through broad thinking. Therefore, CEOs should strive to cultivate proper servant leadership, rather than making efforts focusing on temporary or superficial behavior-oriented servant leadership, to increase the psychological well-being of organization members. When CEOs demonstrate servant leadership to heed the troubles of organization members and motivate them ceaselessly while leading them by example, the psychological well-being of organization members increases.Second, in terms of authentic leadership, the results imply that CEOs should reflect on past behaviors for their growth and maintain their initial commitment through self-reflection. They should try to be consistent with organization members by controlling their emotions and implementing the company’s business plans and goals while considering the capabilities of organization members. The results also imply that CEOs should be undeterred by external pressures, make decisions transparently, put employees at ease, and embrace their flaws. Thereby, CEOs’ authentic leadership increases organization members’ psychological well-being, which leads to progressive thinking and behavior and ultimately serves as a major factor in improving job performance. When the leadership lacks authenticity, CEOs use their relationship with organization members to pursue their own interests, and such leadership obviously has negative effects on the organization members’ psychological well-being.However, CEOs’ ethical leadership did not have a statistically significant effect on organization members’ psychological well-being. This result contradicts the findings of a previous study by Teimouri et al. [52]. If a CEO’s ethical leadership emphasizes honesty and trust morally/legally/normatively, they may be considered inflexible. This also means that if the CEO persuades organization members ethically based on the rules and principles to cooperate, it may disturb the members’ psychological well-being. If the function of goal setting is emphasized only in terms of ethics in an organization, communication may not be clear. Instead, it may disturb the organization members’ psychological well-being, ultimately reducing the function of motivation. Nevertheless, as a means of achieving organization members’ performance goals, CEOs’ ethical leadership is important. In this study, however, CEOs’ ethical leadership did not enhance the function of giving meaning to tasks through the organization members’ psychological well-being.

- Ethical leadership had a statistically positive (+) effect on organizational citizenship behavior. This supports the results of previous studies by Brown and Treviño [188] and Zhu et al. [78] and can be summarized as follows. CEOs should not lie or distort reality morally/legally/normatively and should act based on the principles of fairness and honesty. They should always respect employees as human beings morally/legally/normatively and pursue common interests with the company and employees. Only when the CEO behaves with honesty and trustworthiness morally/legally/normatively can an organization’s members trust and follow them. We found that CEOs’ ethical leadership could increase organizational citizenship behavior among organization members.However, CEOs’ servant and authentic leadership did not have statistically significant effects on organizational citizenship behavior. These results contradict the results of previous studies by Avolio et al. [57], Krog and Govender [182], and Shah et al. [40]. In fact, researchers have emphasized that servant and authentic leadership are very important in business administration and management. However, this study focused on the servant and authentic leadership of CEOs rather than that of immediate superiors and managers. As organizational citizenship behavior of members is voluntary, there is no official reward system internally in the organization. Therefore, various unofficial rewards should be offered to promote it. Particularly, interest and recognition by the immediate superior or manager are more important than the CEO’s leadership in terms of exerting influence on the attitudes and behaviors of on-site organization members. Therefore, on-site leaders have the power to encourage organization members to demonstrate organizational citizenship behavior more actively by closely observing organization members and immediately praising and encouraging them. Herein, however, CEOs’ servant and authentic leadership did not increase organizational citizenship behavior.

- Organization members’ psychological well-being had a statistically significant positive (+) effect on organizational citizenship behavior. This supports the results of previous studies by Huang et al. [60], Kang et al. [90], Kim and Park [197], and Xu et al. [62] and can be summarized as follows. Organizational citizenship behavior increases as psychological well-being increases, that is, organization members embrace life positively, have higher self-esteem (confidence) and clear life goals, take care of work that falls under their responsibilities, live so as to realize their creativity and potential, and are content with the results of life. Organization members with high psychological well-being are more willing to spare time to help busy colleagues at work and try to keep up with organizational changes and innovations. Furthermore, they do not infringe or interfere with the rights of colleagues, voluntarily comply with corporate rules and regulations, and refrain from complaints and unprofessional behavior at work, thereby showing strong organizational citizenship behavior.

5.2. Research Implications

- This study is significant in that it studied CEOs’ sustainable leadership styles in the organizational behavior theory aspect of business administration and psychology and empirically analyzed how these leadership styles affected organization members’ psychological well-being and organizational citizenship behavior. Specially, situational leadership theory and the contingency approach of leadership were utilized and applied based on situational theory. Based on a total of four foundational theories, that is, bottom-up spillover theory, theories of prosocial behavior, and so on, this study empirically analyzed what influence CEOs’ sustainable leadership styles (servant, ethical, and authentic leadership) had on the psychological well-being and organizational citizenship behaviors of organization members.

- CEOs are faced with a number of responsibilities, ranging from being in charge of their company’s performance, to serving as a major spokesperson, to setting strategic directions, maximizing organizational potential, to securing internal and external stakeholders’ participation. Notably, such responsibilities become much more complicated in crisis situations because employees and stakeholders ask CEOs for direction, information, and motivation. Therefore, the results of this study suggest that CEOs’ sustainable leadership styles and actions to improve the possibility of success are extremely important. In other words, they imply that a swift leadership pattern is needed for CEOs to meet the challenges of the times. More specifically: (1) through sustainable leadership, efforts should be made to surpass the general level; (2) important measures should be identified, and preemptive moves should be made; (3) a discriminatory and dynamic approach to strategies should be taken; and (4) positive social objectives should be clearly expressed and practiced. CEOs are attracting more attention than ever, leading companies in today’s rapidly changing times. This suggests that it is necessary to comprehend principles that show when, where, and how important leaders are and the sustainable leadership styles that can increase their chances of success. This study derived constructive implications that CEOs can overcome today’s challenges through sustainable leadership styles.

- Currently, among the various leadership theories, servant leadership, in which the leader serves the organization members based on respect for people and supports them with a serving attitude to unlock their potential [19,24,25,27], is a typical example. In fact, the perspective presented in leadership theories shows only one aspect of this kind of leadership. For example, CEOs’ servant leadership was found to increase organization members’ psychological well-being. However, not everything is solved by servant leadership alone. Depending on the situation, the leader sometimes needs to become an authentic leader as well. In other words, the leader should exhibit multifaceted behavior according to the situation. Therefore, as mentioned earlier, this study derived CEOs’ sustainable leadership styles. In particular, it found that servant and authentic leadership increased organization members’ psychological well-being when applied appropriately.

- An authentic leader sets inner moral standards clearly and then uses those standards to control themselves [20,21,26]. Some scholars have argued that authentic leaders should be sincere and show their inner morals transparently while building relationships with others [53,54,155]. As such, there is an underlying assumption in authentic leadership that if the leader shows authentic behavior rather than instructing organization members, those members watch, learn, and follow [53,54,155]. In other words, the leader should exhibit model behaviors [55,145,189]. Based on fundamental theory, this study showed that CEOs’ authentic leadership could increase organization members’ psychological well-being and had a sustainable effect on it.

- Many CEOs now lead multinational labor groups and face the challenge of working with several stakeholders in different organizational sectors. In an increasingly globalized and flexible organization, it is necessary to educate CEOs on the importance of ethical leadership. The results of this study indicate that organizational citizenship behavior increased when organization members recognized that the CEO had moral values of honesty, fairness, integrity, and transparency. Therefore, this study suggests that CEOs should provide an environment that promotes moral values through official systems (e.g., hiring process and incentive/job promotion system) and the organizational culture’s unofficial elements (e.g., meetings and discussions on ethics, unofficial job promotion procedures perceived within the organization) to exhibit and maintain ethical leadership. CEOs should recognize the importance of moral values in the corporate vision and firmly establish them. Furthermore, CEOs should always engage in work as ethical leaders and inspiring role models for the establishment of these ethical values.

- Ultimately, organizations should recognize the importance of responsibility and sustainability more strongly in the context of business ethics and integrate these elements into their strategic agendas and value norms. The results of this study show CEOs’ ethical responsibility and sustainability. If a CEO makes a decision that lacks ethical values and is not recognized socially, ethical issues from the past to the present accumulate, organization members do not trust the CEO, and organizational citizenship behavior does not grow. Future studies in social science research can focus on CEOs’ ethical leadership and its impacts.

5.3. Limitations and Future Studies

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franklin, A.; Blyton, P. Researching Sustainability: A Guide to Social Science Methods, Practice and Engagement; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, S.H.; Shah, S.M.A.; Khalil, S.M. Sustaining work outcomes through human capital sustainability leadership: Knowledge sharing behaviour as an underlining mechanism. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 1119–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Shuai, C.; Shen, L.; Hou, L.; Zhang, G. A study of sustainable practices in the sustainability leadership of international contractors. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, M.A. Should coaches believe in innate ability? The importance of leadership mindset. Quest 2010, 62, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamfilie, R.; Petcu, A.J.; Draghici, M. The importance of leadership in driving a strategic Lean Six Sigma management. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Chief executive officer ability, corporate social responsibility, and financial performance: The moderating role of the environment. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Terjesen, S.; Umans, T. Corporate governance in entrepreneurial firms: A systematic review and research agenda. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaer, H.; Zaman, M. CEO compensation and sustainability reporting assurance: Evidence from the UK. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagasio, V.; Cucari, N. Corporate governance and environmental social governance disclosure: A meta-analytical review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidu, S. CEO characteristics and firm performance: Focus on origin, education and ownership. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatecola, G.; Cristofaro, M. Ingredients of sustainable CEO behaviour: Theory and practice. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafley, A.G. What only the CEO can do. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 54–62, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, F.E., Jr. Marketing IS management: The wisdom of Peter Drucker. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R. Practical strategic leadership: Aligning human performance development with organizational contribution. Perform. Improv. 2017, 56, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, D.; Mihaiu, N.; Iancu, D. Analysis of human resource management in the military organization from the perspective of Peter Drucker’s vision. Land Forces Acad. Rev. 2015, 20, 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hashem, G. Organizational enablers of business process reengineering implementation: An empirical study on the service sector. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2019, 69, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammassis, C.S.; Kostopoulos, K.C. CEO goal orientations, environmental dynamism and organizational ambidexterity: An investigation in SMEs. Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Eva, N.; Newman, A.; Cooper, B. CEO entrepreneurial leadership and performance outcomes of top management teams in entrepreneurial ventures: The mediating effects of psychological safety. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1119–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbuto, J.E., Jr.; Wheeler, D.W. Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 300–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoes-Jones, F.; Swailes, S. Authentic leadership: Development of a new three pillar model. Strateg. HR Rev. 2015, 14, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Cogliser, C.C.; Davis, K.M.; Dickens, M.P. Authentic leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalshoven, K.; Den Hartog, D.N.; De Hoogh, A.H.B. Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuntia, R.; Suar, D. A scale to assess ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 49, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Meuser, J.D.; Hu, J.; Wu, J.; Liao, C. Servant leadership: Validation of a short form of the SL-28. Leadersh. Q. 2015, 26, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neider, L.L.; Schriesheim, C.A. The authentic leadership inventory (ALI): Development and empirical tests. Leadersh. Q. 2011, 22, 1146–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.L.; Vidaver-Cohen, D.; Colwell, S.R. A new scale to measure executive servant leadership: Development, analysis, and implications for research. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Mahsud, R.; Hassan, S.; Prussia, G.E. An improved measure of ethical leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, B. Leadership agility for organizational agility. J. Creat. Value 2019, 5, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, C.; Vu, H.M. Strategic flexibility, strategic leadership and business sustainability nexus. Int. J. Bus. Environ. 2020, 11, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Dooley, L.M.; Xie, L. How servant leadership and self-efficacy interact to affect service quality in the hospitality industry: A polynomial regression with response surface analysis. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Lyu, Y.; He, Y. Servant leadership and proactive customer service performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 1330–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.; Hamad, M. Servant leadership and academics’ engagement in higher education: Mediation analysis. J. Higher Educ. Policy Manag. 2020, 42, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarence, M.; Devassy, V.P.; Jena, L.K.; George, T.S. The effect of servant leadership on ad hoc schoolteachers’ affective commitment and psychological well-being: The mediating role of psychological capital. Int. Rev. Educ. 2021, 67, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.C.; Chen, S.W. Servant leadership and service performance: A multilevel mediation model. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 1738–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.; Lyubovnikova, J.; Tian, A.W.; Knight, C. Servant leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, moderation, and mediation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 93, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lyu, B.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. How does servant leadership influence employees’ service innovative behavior? The roles of intrinsic motivation and identification with the leader. Baltic J. Manag. 2020, 15, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, M.F.; Bussin, M.H.R.; Geldenhuys, M. Servant leadership and work-related well-being in a construction company. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 43, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, M.F.; Bussin, M.; Geldenhuys, M. The functions of a servant leader. Admin. Sci. 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Batool, N.; Hassan, S. The influence of servant leadership on loyalty and discretionary behavior of employees: Evidence from healthcare sector. J. Bus. Econ. 2019, 11, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, T. The nuts and bolts of ethics, accountability and professionalism in the public sector: An ethical leadership perspective. J. Public Admin. 2008, 43, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Mayer, D.M.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Workman, K.; Christensen, A.L. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 115, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, R. Managing the risk of ethical misconduct disasters as a business continuity strategy. J. Bus. Continuity Emerg. Plan. 2007, 1, 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.G.; Brymer, R.A. The effects of ethical leadership on manager job satisfaction, commitment, behavioral outcomes, and firm performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, A.; Kajalo, S.; Mitronen, L. Exploring the links between ethical leadership, customer orientation and employee outcomes in the context of retailing. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 1642–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conaway, R.N.; Fernandez, T.L. Ethical preferences among business leaders: Implications for business schools. Bus. Commun. Q. 2000, 63, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladkin, D. When deontology and utilitarianism aren’t enough: How Heidegger’s notion of “dwelling” might help organisational leaders resolve ethical issues. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 65, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Ramachandran, I.; Madhavaram, S. Mirroring the boss: Ethical leadership, emulation intentions, and salesperson performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.M.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Mayer, D.M. My boss is morally disengaged: The role of ethical leadership in explaining the interactive effect of supervisor and employee moral disengagement on employee behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Fahrbach, C.M. Doing well by doing good? Analyzing the relationship between CEO ethical leadership and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Kwan, H.K.; Yim, F.H.K.; Chiu, R.K.; He, X. CEO ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility: A moderated mediation model. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, H.; Hosseini, S.H.; Ardeshiri, A. The role of ethical leadership in employee psychological well-being (case study: Golsar Fars Company). J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2018, 28, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iszatt-White, M.; Kempster, S. Authentic leadership: Getting back to the roots of the “root construct”? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyon, T.P.; Houghton, J.D.; Simarasl, N.; Dawley, D.D.; Howe, M. Limits of authenticity: How organizational politics bound the positive effects of authentic leadership on follower satisfaction and performance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnese, M.L.; Zaghini, F.; Caruso, R.; Fida, R.; Romagnoli, M.; Sili, A. Managing care errors in the wards: The contribution of authentic leadership and error management culture. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, A.S.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. Authentic leadership, happiness at work and affective commitment: An empirical study in Cape Verde. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Morgeson, F.P.; Nahrgang, J.D. Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader–follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rie, J.I. Anger, anxiety, depression in the workplace: Differences of evoking causes and coping methods among emotions, Relationships of emotion regulation and psychological well-being, job effectiveness. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2003, 16, 19–58. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, N.; Qiu, S.; Yang, S.; Deng, R. Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Mediation of trust and psychological well-being. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H.; Ji, Y.H.; Baek, W.Y.; Byon, K.K. Structural relationship among physical self-efficacy, psychological well-being, and organizational citizenship behavior among hotel employees: Moderating effects of leisure-time physical activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xie, B.; Chung, B. Bridging the gap between affective well-being and organizational citizenship behavior: The role of work engagement and collectivist orientation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersemaekers, W.; Rupprecht, S.; Wittmann, M.; Tamdjidi, C.; Falke, P.; Donders, R.; Speckens, A.; Kohls, N. A workplace mindfulness intervention may be associated with improved psychological well-being and productivity. A preliminary field study in a company setting. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.M.; Kim, H.S. The study on the moderating effect of psychological well-being between the multiple roles of married flight attendants and job performance. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 33, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.A.; Roloff, M.E. Organizational citizenship behavior, organizational communication, and burnout: The buffering role of perceived organizational support and psychological contracts. Commun. Q. 2015, 63, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasra, M.A.; Heilbrunn, S. Transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior in the Arab educational system in Israel: The impact of trust and job satisfaction. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 2016, 44, 380–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, F.T.; Desai, K.; Jayakrishnan, K. Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): A comprehensive literature review. Sumedha J. Manag. 2016, 5, 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- De Geus, C.J.C.; Ingrams, A.; Tummers, L.; Pandey, S.K. Organizational citizenship behavior in the public sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Public Admin. Rev. 2020, 80, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Peiró, J.M. Human capital sustainability leadership to promote sustainable development and healthy organizations: A new scale. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, J.; Pearse, N.; Dimovski, V. Strategic decision making for organizational sustainability: The implications of servant leadership and sustainable leadership approaches. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2015, 17, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.J.; Kang, E. Environmental issues as an indispensable aspect of sustainable leadership. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuryani, E.; Rodli, A.F.; Sutarsi, S.; Dewi, N.N.; Arif, D. Analysis of decision support system on situational leadership styles on work motivation and employee performance. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, C.; Luo, A.; Zhang, P.; Deng, A. A meta-analysis of transformational leadership in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2137–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, R. Vision of effective leadership. Int. J. Bus. Admin. 2017, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, V.; Ashraf Ali, M. A systematic review of various leadership theories. Shanlax Int. J. Com. 2020, 8, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emuwa, A.; Fields, D. Authentic leadership as a contemporary leadership model applied in Nigeria. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Dooley, L.M.; Zhang, R. The effects of authentic leadership on trust in leaders, organizational citizenship behavior, and service quality in the Chinese hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; May, D.R.; Avolio, B.J. The impact of ethical leadership behavior on employee outcomes: The roles of psychological empowerment and authenticity. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2004, 11, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cubero, C.G. Situational leadership and persons with disabilities. Work 2007, 29, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Graeff, C.L. The situational leadership theory: A critical view. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1983, 8, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P. Situational Leadership Theory: An examination of a prescriptive theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Kiyani, S.K.; Dust, S.B.; Zakariya, R. The impact of ethical leadership on project success: The mediating role of trust and knowledge sharing. Int. J. Manag. Projects Bus. 2021, 14, 982–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, B.Y. Customizing leadership practices for the millennial workforce: A conceptual framework. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 1930865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, D.; Nafukho, F.M. Can authentic leadership influence the employees’ organizational justice perceptions?—A study in the hotel context. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscocco, K.A.; Roschelle, A.R. Influences on the quality of work and nonwork life: Two decades in review. J. Vocat Behav. 1991, 39, 182–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Efraty, D.; Siegel, P.; Lee, D.J. A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 55, 241–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, Y.G.; Woo, E. Examining the impacts of touristification on quality of life (QOL): The application of the bottom-up spillover theory. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 41, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Ahn, J.C.; Kim, B.S.; Choi, H.J. Social networking sites self-image antecedents of social networking site addiction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Towards a new concept of residential well-being based on bottom-up spillover and need hierarchy theories. In A Life Devoted to Quality of Life; Maggino, F., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 60, pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Li, Y. How to fuel employees’ prosocial behavior in the hotel service encounter. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 84, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Qu, H. The mediating roles of gratitude and obligation to link employees’ social exchange relationships and prosocial behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A.P.; Motowidlo, S.J. Prosocial organizational behaviors. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1986, 11, 710–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, B.L.; Meglino, B.M. The role of dispositional and situational antecedents in prosocial organizational behavior: An examination of the intended beneficiaries of prosocial behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, E.R.; Detert, J.R.; Chiaburu, D.S. Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 912–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.Y.; Kwun, S.K. On employee voice and silence: The effects of three leaderships styles and their consequences. Korean J. Manag. 2015, 23, 43–71. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, E.W.; Milliken, F.J. Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyne, L.V.; Ang, S.; Botero, I.C. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. J. Manag. Stud. 2003, 40, 1359–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quiros, M.D.M.; Miralles-Quiros, J.L.; Arraiano, I.G. Sustainable development, sustainability leadership and firm valuation: Differences across Europe. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiengarten, F.; Lo, C.K.Y.; Lam, J.Y.K. How does sustainability leadership affect firm performance? The choices associated with appointing a chief officer of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive healthy organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive relational management for healthy organizations: Psychometric properties of a new scale for prevention for workers. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiró, J.M.; Ayala, Y.; Tordera, N.; Lorente, L.; Rodríguez, I. Bienestar sostenible en el trabajo: Revisión y reformulación. Pap. Psicólogo 2014, 35, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppila, O.P.; Ehrnrooth, M.; Mäkelä, K.; Smale, A.; Sumelius, J.; Vuorenmaa, H. Serving to help and helping to serve: Using servant leadership to influence beyond supervisory relationships. J. Manag. 2021, 0149206321994173, Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Lee, H.W.; Johnson, R.E.; Lin, S. Serving you depletes me? A leader-centric examination of servant leadership behaviors. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1185–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; van Dierendonck, D. Serving the need of people: The case for servant leadership against populism. J. Change Manag. 2021, 21, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollberger, J.; Las Heras, M.; Rofcanin, Y.; Bosch, M.J. Serving followers and family? A trickle-down model of how servant leadership shapes employee work performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 112, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Meng, L.; Cai, S. Servant leadership and innovative behavior: A moderated mediation. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.Q.; Spears, L.C. Servant-leadership and community: Humanistic perspectives from Pope John XXIII and Robert K. Greenleaf. Humanist. Manag. J. 2020, 5, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.E. Old Testament view of Robert Greenleaf’s Servant Leadership Theory. J. Bibl. Perspect. Leadersh. 2019, 9, 304–318. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.R. Critical analysis of Robert K. Greenleaf’s servant leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Int. J. Lang. Lit. 2018, 6, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.; Sudan, K.; Satini, S.; Sunarsi, D. Organizational servant leadership. Int. J. Educ. Amin. Manag. Leadersh. 2020, 1, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Latif, K.F.; Ahmad, M.S. Servant leadership and employee innovative behaviour: Exploring psychological pathways. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Karatepe, O.M. Does servant leadership better explain work engagement, career satisfaction and adaptive performance than authentic leadership? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2075–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gu, J.; Liu, H. Servant leadership and employee creativity: The roles of psychological empowerment and work–family conflict. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Aboramadan, M.; Dahleez, K.A. Does climate for creativity mediate the impact of servant leadership on management innovation and innovative behavior in the hotel industry? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2497–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.J.; Wang, L. How and when servant leaders enable collective thriving: The role of team–member exchange and political climate. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A. Servant leadership and perceived employability: Proactive career behaviours as mediators. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. Emotional intelligence, servant leadership, and development goal orientation in athletic directors. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, K.; Xi, R.; Zhang, X. Servant leadership and career success: The effects of career skills and proactive personality. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzari, M.; Karatepe, O.M. Does optimism mediate the influence of work-life balance on hotel salespeople’s life satisfaction and creative performance? J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 19, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.; Newman, A.; Menzies, J.; Zheng, C.; Fermelis, J. Work–life balance in Asia: A systematic review. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.S.; Heine, G.; Mahembe, B. Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M. The moral entrepreneur: A new component of ethical leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, A.; Páez, I. Developing a framework for ethical leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.; Roche, M.; Brougham, D. Indigenous insights into ethical leadership: A study of Māori leaders. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, Y.L.; Tang, P.M.; Shao, R.; Lam, L.W. Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Reimagining ethical leadership as a relational, contextual and political practice. Leadership 2017, 13, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Farooq, O. Corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership: Investigating their interactive effect on employees’ socially responsible behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Cerchione, R.; Singh, R.; Dahiya, R. Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A systematic review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Ma, J.; Bartnik, R.; Haney, M.H.; Kang, M. Ethical leadership: An integrative review and future research agenda. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.H., Jr.; Dimitriou, C.K. Using ethical leadership to reduce job stress and improve performance quality in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenuto, P.L.; Gardiner, M.E. Interactive dimensions for leadership: An integrative literature review and model to promote ethical leadership praxis in a global society. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2018, 21, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Nadeem, S. Understanding the unique impact of dimensions of ethical leadership on employee attitudes. Ethics Behav. 2019, 29, 572–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Agrawal, R.; Khandelwal, U. Developing ethical leadership for business organizations: A conceptual model of its antecedents and consequences. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 712–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, X. Just the right amount of ethics inspires creativity: A cross-level investigation of ethical leadership, intrinsic motivation, and employee creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, R.A.; Atan, T. The influence of ethical leadership on academic employees’ organizational citizenship behavior and turnover intention: Mediating role of intrinsic motivation. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 583–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. The Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS): Italian adaptation and exploration of the nomological network in a health care setting. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M.; Ashktorab, T.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F. Ethical leadership outcomes in nursing: A qualitative study. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, A.; Achen, R.M. Explicating the synergies of self-determination theory, ethical leadership, servant leadership, and emotional intelligence. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2018, 12, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, B.P.; Prasad, T.; Nair, S.K. Exploring authentic leadership through leadership journey of Gandhi. Qual. Rep. 2021, 26, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alilyyani, B.; Wong, C.A.; Cummings, G. Antecedents, mediators, and outcomes of authentic leadership in healthcare: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 83, 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, M.K.A.; Khasawneh, S.; Alruz, J.A.; Bataineh, O.T. Authentic leadership practices in the university setting: The theory of tomorrow. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 14, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriveau, A.M. Developing authentic leadership as a starting point to responsible management: A Canadian university case study. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y. Crafting employee trust: From authenticity, transparency to engagement. J. Commun. Manag. 2018, 22, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Shen, H. Toward a relational theory of employee engagement: Understanding authenticity, transparency, and employee behaviors. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2020, 2329488420954236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempster, S.; Iszatt-White, M.; Brown, M. Authenticity in leadership: Reframing relational transparency through the lens of emotional labour. Leadership 2019, 15, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.A.; Green, M.T.; Sun, Y.; Baggerly-Hinojosa, B. Authentic leadership and transformational leadership: An incremental approach. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2017, 11, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; Wolyniec, N.; Okimoto, T.G.; Mols, F.; Haslam, S.A.; Kay, A.A. Knowing me, knowing us: Personal and collective self-awareness enhances authentic leadership and leader endorsement. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 32, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghoul, A.; Elrehail, H.; Emeagwali, O.L.; AlShboul, M.K. Knowledge management, workplace climate, creativity and performance: The role of authentic leadership. J. Workplace Learn. 2018, 30, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, O.K.; Espevik, R. Moral antecedents of authentic leadership: Do moral justice reasoning, self-importance of moral identity and psychological hardiness stimulate authentic leadership? Cogent Psychol. 2017, 4, 1382248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y.M.; Rowe, W.G. A reconceptualization of authentic leadership: Leader legitimation via follower-centered assessment of the moral dimension. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loon, M.; Otaye-Ebede, L.; Stewart, J. The paradox of employee psychological well-being practices: An integrative literature review and new directions for research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 156–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, D.; Iranmanesh, M.; Foroughi, B. Personality traits, psychological well-being, Facebook addiction, health and performance: Testing their relationships. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasim, E.D. Relationships between psychological well-being, happiness, and educational satisfaction in a group of university music students. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 10, 2198–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Heizomi, H.; Allahverdipour, H.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.A.; Safaian, A. Happiness and its relation to psychological well-being of adolescents. Asian J. Psychiatry 2015, 16, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M. More time on technology, less happiness? Associations between digital-media use and psychological well-being. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Sheldon, K.M. Clarifying the concept of well-being: Psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective well-being. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, C.W.; Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L. Get active? A meta-analysis of leisure-time physical activity and subjective well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, L.; Acedillo, V.; Bacunador, A.M.; Balo, C.C.; Lagdameo, Y.J.; Tupa, N.S. A historical review of the development of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and its implications for the twenty-first century. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 821–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.C. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, M. Organizational citizenship behavior in relation to employees’ intention to stay in Indian organizations. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1355–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanzeb, K.; Mohanty, J. The mediating role of organizational commitment between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: Power distance as moderator. Pers. Rev. 2019, 49, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R.K.; Goswami, R. Exploring the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and job satisfaction among shift workers in India. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2013, 32, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, G.; Wayne, S.J. Underlying motives of organizational citizenship behavior: Comparing egoistic and altruistic motivations. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2015, 22, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, G. Individual initiative and burnout as antecedents of employee expediency and the moderating role of conscientiousness. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 110, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnipseed, D.L.; VandeWaa, E.A. The little engine that could: The impact of psychological empowerment on organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Organ. Theor. Behav. 2020, 23, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosapour, S.; Feizi, M.; Alipour, H. Spiritual intelligence relationship with organizational citizenship behavior of high school teachers in Germi city. J. Bus. Manag. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 2, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Karabay, M.E. An investigation of the effects of work-related stress and organizational commitment on organizational citizenship behavior: A research on banking industry. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 6, 282–302. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.H.J.; Kuok, O.M.K. Antecedents of civic virtue and altruistic organizational citizenship behavior in Macau. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2021, 16, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, W.; Diestel, S.; Schmidt, K.H. The positive relationship between servant leadership and employees’ psychological health: A multi-method approach. Ger. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 28, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.; Boudrias, J.S.; Brunet, L.; Morin, D.; De Civita, M.; Savoie, A.; Alderson, M. Authentic leadership and psychological well-being at work of nurses: The mediating role of work climate at the individual level of analysis. Burnout Res. 2014, 1, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernis, M.H.; Goldman, B.M. A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 38, 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Macik-Frey, M.; Quick, J.C.; Cooper, C.L. Authentic leadership as a pathway to positive health. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.M.; Luthans, F. Relationship between entrepreneurs’ psychological capital and their authentic leadership. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 254–273. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, J.A. Servant leadership and transformational leadership: From comparisons to farewells. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Sendjaya, S.; Prajogo, D.; Cavanagh, A.; Robin, M. Creating strategic fit: Aligning servant leadership with organizational structure and strategy. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krog, C.L.; Govender, K. The relationship between servant leadership and employee empowerment, commitment, trust and innovative behaviour: A project management perspective. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Cooper, B.; Sendjaya, S. How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerpott, F.H.; Van Quaquebeke, N.; Schlamp, S.; Voelpel, S.C. An identity perspective on ethical leadership to explain organizational citizenship behavior: The interplay of follower moral identity and leader group prototypicality. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 156, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacmar, K.M.; Andrews, M.C.; Harris, K.J.; Tepper, B.J. Ethical leadership and subordinate outcomes: The mediating role of organizational politics and the moderating role of political skill. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M.J.; Wu, C.; Roberts, J.A. The influence of ethical leadership and regulatory focus on employee outcomes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Cho, D.; Lim, D.H. Authentic leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of practicing core values. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J. Authentic leadership development. Posit. Organ. Sch. 2003, 16, 241–271. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.K.; Jo, S.J. The effects of perceived authentic leadership and core self-evaluations on organizational citizenship behavior: The role of psychological empowerment as a partial mediator. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Duarte, A.P.; Filipe, R. How authentic leadership promotes individual performance: Mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior and creativity. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 1585–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.; Truss, C. The link between perceived HRM practices, performance and well-being: The moderating effect of trust in the employer. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soane, E.; Truss, C.; Alfes, K.; Shantz, A.; Rees, C.; Gatenby, M. Development and application of a new measure of employee engagement: The ISA Engagement Scale. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2012, 15, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyu Park, J.; Sik Kim, J.; Yoon, S.W.; Joo, B. The effects of empowering leadership on psychological well-being and job engagement: The mediating role of psychological capital. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Park, W.W. Psychological well-being in workplace: A review and meta-analysis. Korean J. Manag. 2017, 25, 15–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.T.; Chan, A.C.M. Measuring psychological well-being in the Chinese. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2005, 38, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kállay, É.; Rus, C. Psychometric properties of the 44-item version of Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 30, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dierendonck, D. The construct validity of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-being and its extension with spiritual well-being. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2004, 36, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. The effects of organizational citizenship behavior on burnout and organizational commitment. Korean Manag. Rev. 2012, 41, 693–722. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, V.; Jain, S. A scale for measuring organizational citizenship behavior in manufacturing sector. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2014, 6, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Beeri, I.; Birman-Shemesh, T.; Somech, A. Group-level organizational citizenship behavior in the education system: A scale reconstruction and validation. Educ. Admin. Q. 2007, 43, 462–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.S.; Kim, J.H. Performing arts and sustainable consumption: Influences of consumer perceived value on ballet performance audience loyalty. J. Psychol. Afr. 2021, 31, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, G.J.; Choi, H.J.; Seok, B.I.; Lee, N.H. Effects of social network services (SNS) subjective norms on SNS addiction. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Roh, J.S.; Choi, H.J. Success factors and sustainability of the K-pop industry: A structural equation model and fuzzy set analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.E.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, J.E.; Choi, H.J. Korean dance performance influences on prospective tourist cultural products consumption and behaviour intention. J. Psychol. Afr. 2019, 29, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, J.H. Brand loyalty and the Bangtan Sonyeondan (BTS) Korean dance: Global viewers’ perceptions. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Operational Definition | Measured Item | Researchers (Sources) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Servant Leadership | The style of leadership in which the leader serves the organization members based on respect for people and supports them with a serving attitude to unlock their potentials. | 1. Our company’s CEO has listening/communicating/coordinating attitudes and makes effort to build empathy. (Coordinating) | |

| 2. Our company’s CEO shows interest in healing the pains of organization members and supports capability development. (Assistance) | |||

| 3. Our company’s CEO serves with a humble attitude and makes an effort to work together based on persuasion instead of blind obedience. (Service) | |||

| 4. Our company’s CEO provides alternatives through clear awareness and presents vision through broad thinking. (Presenting direction/vision) | |||

| 5. Our company’s CEO helps predict the future with keen insights and build the community among organization members. (Assistance) | |||

| Ethical Leadership | The ability to demonstrate morally/legally/normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relations and promoting such actions to organization members through communication, support, and decision-making. | 1. Our company’s CEO does not lie or distort reality morally/legally/normatively. (Honesty) | |

| 2. Our company’s CEO has principles of fairness and honesty morally/legally/normatively. (Justice) | |||

| 3. Our company’s CEO always respects employees morally/legally/normatively. (Respect) | |||

| 4. Our company’s CEO pursues common interests (with the company, employees) morally/legally/normatively. (Community) | |||

| 5. Our company’s CEO behaves with honesty and trustworthiness morally/legally/normatively. (Integrity) | |||

| Authentic Leadership | Establishing firm values and principles based on clear self-awareness and having positive effects on the organization members by forming transparent relationships. | 1. Our company’s CEO grows by reflecting on past behaviors. (Self-awareness) | |

| 2. Our company’s CEO maintains initial commitment through self-reflection. (Self-awareness) | |||

| 3. Our company’s CEO tries to be consistent with employees by controlling their own emotions. (Transparency) | |||

| 4. Our company’s CEO implements the company’s business plans and goals by considering the capabilities of the employees. (Processing) | |||

| 5. Our company’s CEO is undeterred by external pressure, makes decisions transparently, puts the employees at ease, and embraces their flaws. (Morality) | |||

| Psychological Well-being | The degree to which one lives in the direction of positively embracing life, having clear goals, and realizing their potentials. | 1. I embrace life positively and live with self-esteem (confidence). | |

| 2. I have clear life goals and take care of work that falls under my responsibility. | |||

| 3. Compared to people around me, I am happy and content with my life overall. | |||

| 4. I manage personal/company or financial problems properly and live morally. | |||

| 5. I try to realize creativity and potentials, and I am content with the results of my life. | |||

| Organizational Citizenship Behavior | The degree to which an organization member voluntarily supports organizational development without proper compensation despite it not being official work. | 1. I am willing to spare some time to help busy colleagues. (Altruism) | |

| 2. I try to keep up with organizational changes and innovations. (Civic Virtue) | |||

| 3. I try not to infringe or interfere with the rights of my colleagues. (Courtesy) | |||

| 4. I comply with the corporate rules and regulations voluntarily. (Conscientiousness) | |||

| 5. I refrain from complaints and private behavior at work. (Sportsmanship) |

| Item | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 326 | 50.2 |

| Female | 323 | 49.8 | |

| Age | 20s | 103 | 15.9 |

| 30s | 178 | 27.4 | |

| 40s | 179 | 27.6 | |

| 50s | 189 | 29.1 | |

| Education | High school graduate | 106 | 16.3 |

| Technical college graduate | 120 | 18.5 | |

| University graduate | 328 | 50.5 | |

| Graduate school graduate | 95 | 14.6 | |

| Monthly Income (Personal) | 2 million KRW or less | 207 | 31.9 |

| 2.01–3.00 million KRW | 133 | 20.5 | |

| 3.01–4.00 million KRW | 100 | 15.4 | |

| 4.01–5.00 million KRW | 81 | 12.5 | |

| 5.01 million KRW or higher | 128 | 19.7 | |

| Race | White | 316 | 48.7 |

| Asian | 226 | 34.8 | |

| Black | 107 | 16.5 | |

| Nationality | South Korea | 208 | 32.0 |

| The United States | 143 | 22.0 | |

| The United Kingdom | 139 | 21.4 | |

| South Africa | 159 | 24.5 | |

| Corporate Size (Including Subsidiaries) | Midsize companies | 440 | 67.8 |

| Large enterprises | 209 | 32.2 | |

| Variable | Item | Convergent Validity | Cronbach’s Alpha | Multicollinearity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outer Loadings | Composite Reliability | AVE | VIF | |||

| Servant leadership | Servant leadership 1 | 0.884 | 0.943 | 0.768 | 0.924 | 3.418 |

| Servant leadership 2 | 0.883 | 3.456 | ||||

| Servant leadership 3 | 0.884 | 3.185 | ||||

| Servant leadership 4 | 0.851 | 2.515 | ||||

| Servant leadership 5 | 0.879 | 2.965 | ||||

| Ethical leadership | Ethical leadership 1 | 0.880 | 0.955 | 0.810 | 0.941 | 3.093 |

| Ethical leadership 2 | 0.901 | 3.558 | ||||

| Ethical leadership 3 | 0.913 | 3.872 | ||||

| Ethical leadership 4 | 0.894 | 3.459 | ||||

| Ethical leadership 5 | 0.911 | 3.768 | ||||

| Authentic leadership | Authentic leadership 1 | 0.880 | 0.948 | 0.785 | 0.932 | 3.390 |

| Authentic leadership 2 | 0.904 | 3.919 | ||||

| Authentic leadership 3 | 0.857 | 2.647 | ||||

| Authentic leadership 4 | 0.886 | 3.172 | ||||

| Authentic leadership 5 | 0.902 | 3.582 | ||||

| Psychological well-being | Psychological well-being 1 | 0.808 | 0.905 | 0.655 | 0.868 | 2.013 |

| Psychological well-being 2 | 0.832 | 2.123 | ||||

| Psychological well-being 3 | 0.826 | 2.121 | ||||

| Psychological well-being 4 | 0.802 | 1.993 | ||||

| Psychological well-being 5 | 0.776 | 1.831 | ||||

| Organizational citizenship behavior | Organizational citizenship behavior 1 | 0.756 | 0.875 | 0.585 | 0.823 | 1.669 |

| Organizational citizenship behavior 2 | 0.795 | 1.827 | ||||

| Organizational citizenship behavior 3 | 0.758 | 1.778 | ||||

| Organizational citizenship behavior 4 | 0.784 | 1.916 | ||||

| Organizational citizenship behavior 5 | 0.728 | 1.662 | ||||

| Variable | Servant Leadership | Ethical Leadership | Authentic Leadership | Psychological Well-Being | Organizational Citizenship Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servant leadership | 0.876 | — | — | — | — |

| Ethical leadership | 0.698 | 0.900 | — | — | — |

| Authentic leadership | 0.685 | 0.696 | 0.886 | — | — |

| Psychological well-being | 0.587 | 0.590 | 0.600 | 0.809 | — |

| Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.557 | 0.577 | 0.573 | 0.669 | 0.765 |

| Path | Β-Value | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | t-Value | p-Value | Hypothesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Servant leadership | → | Psychological well-being | 0.173 | 0.172 | 0.085 | 2.046 | 0.041 | Supported |

| H2 | Ethical leadership | → | Psychological well-being | 0.173 | 0.177 | 0.095 | 1.812 | 0.071 | Not supported |

| H3 | Authentic leadership | → | Psychological well-being | 0.292 | 0.291 | 0.086 | 3.399 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4 | Servant leadership | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.089 | 0.155 | 0.877 | Not supported |

| H5 | Ethical leadership | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.184 | 0.185 | 0.090 | 2.039 | 0.042 | Supported |

| H6 | Authentic leadership | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.100 | 0.103 | 0.090 | 1.121 | 0.263 | Not supported |

| H7 | Psychological well-being | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.493 | 0.492 | 0.047 | 10.403 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Path | Β-Value | Sample Mean | Standard Deviation | t-Value | p-Value | Mediated Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Servant leadership | → | Psychological well-being | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.085 | 0.084 | 0.043 | 2.004 | 0.046 | Yes |

| 2 | Ethical leadership | → | Psychological well-being | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.085 | 0.087 | 0.048 | 1.762 | 0.079 | No |

| 3 | Authentic leadership | → | Psychological well-being | → | Organizational citizenship behavior | 0.144 | 0.144 | 0.045 | 3.186 | 0.002 | Yes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, H.-j. Effect of Chief Executive Officer’s Sustainable Leadership Styles on Organization Members’ Psychological Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413676

Choi H-j. Effect of Chief Executive Officer’s Sustainable Leadership Styles on Organization Members’ Psychological Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413676

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Hyun-ju. 2021. "Effect of Chief Executive Officer’s Sustainable Leadership Styles on Organization Members’ Psychological Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413676

APA StyleChoi, H.-j. (2021). Effect of Chief Executive Officer’s Sustainable Leadership Styles on Organization Members’ Psychological Well-Being and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability, 13(24), 13676. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413676