Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Economic Diversification

2.2. Human Capital Enhancement

2.2.1. Education

2.2.2. University-Industry Partnership

- Lack of precise requirements from industry regarding what majors are needed in terms of either quality or quantity. The broken chain between educational supply and industrial demand is negatively influencing many aspects, including student motivation and financial impacts. In short, universities are supplying random solutions to unspecified problems [49].

- The absence of a collaborative environment between educational institutions and industry that aims to create an innovative field of research based on the partnership of key industry actors while also supporting local industry-driven research, development, and innovation (RDI) [50].

- A shortage of partnership strategies between industry, universities, and K-12 institutes―especially in terms of development in the areas of technology, research, and innovation [51].

2.2.3. Attracting Global Human Capital

2.3. Women’s Empowerment: Female Entrepreneurship

3. Methodology

3.1. Systems Thinking: Conceptual Model Development

3.2. Validation: Semi-Structured Interviews

3.2.1. Sampling and Participant Selection

3.2.2. Data Analysis

Data Reduction

Data Display

3.2.3. Validity

4. Results and Discussion

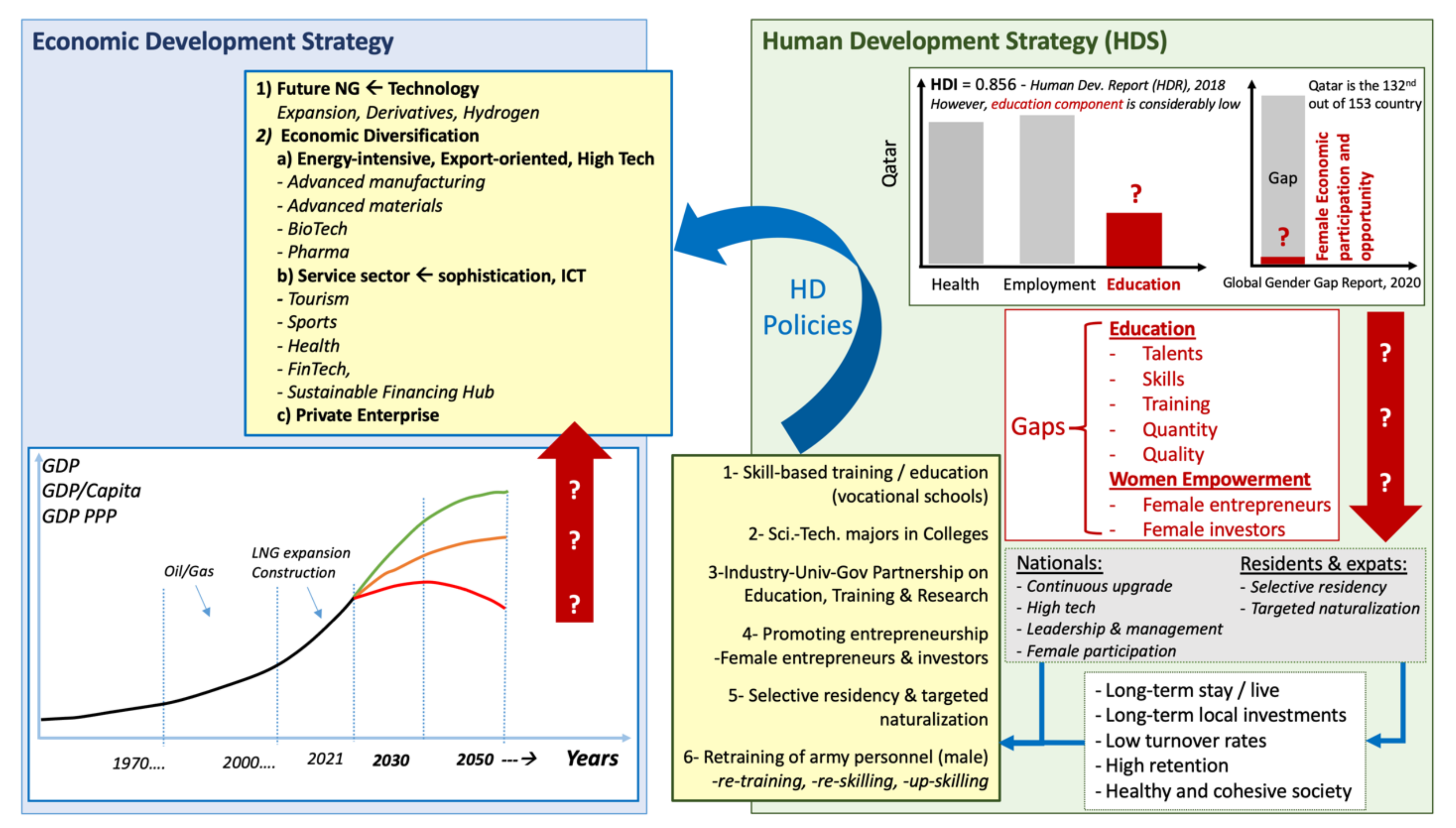

4.1. The Conceptual Model: Human Capital Enhancement and Female Empowerment for Economic Diversification

4.2. Validation and Discussion: Semi-Structured Interview Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Agreement Levels of the Interviewees and Their Reasons

| Policy | Average Agreement Level | High-Level Validation | Medium-Level Validation | Low-Level Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1: Redesign curriculum to focus on vocational high schools providing skill-based training and education | High | IR1, IR2, IR3, IR5, IR7, IR9, IR11, R13, R14 | IR4, IR6, IR8, IR10, IR12, R15 | |

| P2: Increase science and technology majors and entrepreneurship training for all majors in colleges | High | IR1, IR6, IR7, IR9, IR11, IR12, IR13, IR14, IR15 | IR2, R4. IR5, IR8, IR10 | IR3 |

| P3: Establish industry-university-government partnerships on education, training, and research | High | IR1, R2, IR3, IR5, IR6, IR7, IR8, IR10, IR11, IR12, IR13, IR15 | IR4, IR9, IR14 | |

| P4: Promote entrepreneurship, particularly for female entrepreneurs and investors | Medium | IR1, IR3, IR5, IR6, IR8, IR13 | IR2, IR4, IR7, IR9, IR10, IR11, IR12, IR14, IR15 | |

| P5: Provide selective permanent residency for highly skilled expats and targeted naturalization | Medium | IR6, IR7, IR9, IR15 | IR3, IR4, IR8, IR10, IR11, IR12, IR13, IR14 | IR1, IR2, IR5 |

| P6: Retrain army personnel for extra skills by re-educating them in a non-military college | Medium | R1, R2, R4, R5, R10, R11, R12 | R3, R6, R7, R8, R9, R13, R14, R15 |

| Policy | Reasons for Medium-Level Validation | Reasons for Low-Level Validation |

|---|---|---|

| P1: Redesign curriculum to focus on vocational high schools providing skill-based training and education |

| |

| P2: Increase science and technology majors and entrepreneurship training at all majors in colleges |

|

|

| P3: Establish industry-university-government partnership on education, training, and research |

| |

| P4: Promote entrepreneurship, particularly for female entrepreneurs and investors |

| |

| P5: Provide selective permanent residency for highly skilled expats and targeted naturalization |

|

|

| P6: Retrain army personnel for extra skills by re-educating them in a non-military college |

|

References

- Costantini, V.; Monni, S. Sustainable human development for European countries. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, P.; Lemille, A.; Desmond, P. Making the circular economy work for human development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiker, B.F. Human Capital: In Retrospect; University of South Carolina, Bureau of Business and Economic Research: Columbia, SC, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Blaug, M. The Empirical Status of Human Capital Theory: A Slightly Jaundiced Survey. J. Econ. Lit. 1976, 14, 827–855. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetland, S. Human Capital Theory: Foundations of a Field of Inquiry. Rev. Educ. Res. 1996, 66, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterton, J.; Cafferkey, K. Revisiting human capital theory: Progress and prospects. In Elgar Introduction to Theories of Human Resources and Employment Relations; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, uk, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, L.; Biddle, J. The introduction of human capital theory into education policy in the United States. Hist. Polit. Econ. 2017, 49, 537–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeonova-Ganeva, R. Human Capital in Economic Growth: A Review of Theory and Empirics. Икoнoмическа Мисъл 2010, 7, 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Front matter, preface. In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education, 1st ed.; NBER: New York, NY, USA, 1964; pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Almendarez, L. Human capital theory: Implications for educational development in Belize and the Caribbean. Caribb. Q. 2013, 59, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Building Knowledge Economies: Advanced Strategies for Development; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Amsden, A.H. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y. Vocational Education and Training in Korea: Achieving the Enhancement of National Competitiveness; KRIVET: Sejong-si, Korea, 2014; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K. Assessment for learning reform in Singapore—Quality, sustainable or threshold? In Assessment Reform in Education; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Achoui, M.M. Human resource development in Gulf countries: An analysis of the trends and challenges facing Saudi Arabia. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2009, 12, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Darnall, N.; Husted, B.W. Sustainability strategy in constrained economic times. Long Range Plan. 2015, 48, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSparren, J.; Besada, H.; Saravade, V. Qatar’s Global Investment Strategy for Diversification and Security in the Post-Financial Crisis Era’; Centre on Governance, University of Ottawa: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ari, I.; Akkas, E.; Asutay, M.; Koç, M. Public and private investment in the hydrocarbon-based rentier economies: A case study for the GCC countries. Resour. Policy 2019, 62, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetais, S.; Mohsin, A. Assessing Qatar’s Readiness and Potential for the Development of a Knowledge Based Economy: An Empirical Analysis of Its Policies, Progress and Perceptions. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meza, A.; Ari, I.; Al-sada, M.S.; Koç, M. Future LNG competition and trade using an agent-based predictive model. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 38, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, S.; Zhengliang, X.; Hussain, H. The Mediating Effect of customer satisfaction on the relationship between Electronic banking service quality and customer Purchase intention: Evidence from the Qatar banking sector. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020935887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.R. Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Development Planning and Statistics. Realising Qatar National Vision 2030 The Right to Development; Qatar’s Fourth National Human Development Report; Al Rayyan Printing Press: Doha, Qatar, 2015; pp. 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- Almaamory, A.T.; Al Slik, G. Science and Technology Park as an Urban Element Towards Society Scientific Innovation Evolution. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Engineering Science and Technology (ICEST 2020), Samawah, Iraq, 23–24 December 2020; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1090, p. 12119. [Google Scholar]

- Doha University for Science, Technology to be Established. Available online: https://www.gulf-times.com/story/692955/Doha-University-for-Science-Technology-to-be-estab (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Ibrahim, I.; Harrigan, F. Qatar’s economy: Past, present and future. Qsci. Connect 2012, 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.Y.; Zhang-Zhang, Y. Insights on women’s labor participation in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QF. Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser. Available online: https://www.mozabintnasser.qa/en (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Joseph, S. 9 Qatari Women Who Are Inspiring Future Generations to Make an Impact—Emirates Woman. Available online: https://emirateswoman.com/inspiring-women-from-qatar/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Planning and Statistics Authority in Qatar Woman and Man in the State of Qatar, a Statistical Profile; Planning and Statistics Authority in Qatar: Doha, Qatar, 2018.

- Abdallah, H. Qatari Women ‘Outnumber Men’ at Local Universities. Available online: https://www.dohanews.co/qatari-women-outnumber-men-at-local-universities/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Al-Suwaidi, J.S. Towards a Strategy to Build Administrative Capacity in Light of Human Development for Qatar National Vision 2030. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bolton, Bolton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoklinova, M. Mixed economy and economic efficiency: Current issues and challenges. Research Gate. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312409943_MIXED_ECONOMY_AND_ECONOMIC_EFFICIENCY_CURRENT_ISSUES_AND_CHALLENGES (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurship, social capital, and institutions: Social and commercial entrepreneurship across nations. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2013, 37, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EY Norway. Norwegian Oilfield Services Analysis 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_no/oil-gas/norwegian-oilfield-services-analysis-2020 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Skarholt, K.; Blix, E.H.; Sandsund, M.; Andersen, T.K. Health promoting leadership practices in four Norwegian industries. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 31, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamara, M. The switching impact of financial stability and economic growth in Qatar: Evidence from an oil-rich country. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2019, 73, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardella, G.M.; Hernández-Sánchez, B.R.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Women entrepreneurship: A systematic review to outline the boundaries of scientific literature. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazandjian, R.; Kolovich, M.L.; Kochhar, M.K.; Newiak, M.M. Gender Equality and Economic Diversification; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, R.; Marlet, E. Foreign Direct Investment and Women Empowerment: New Evidence on Developing Countries; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cuberes, D.; Teignier, M. Gender inequality and economic growth: A critical review. J. Int. Dev. 2014, 26, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlelmula, F.; Koc, M. Overall Review of Education System in Qatar; Lambert Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2016; Volume 20, p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parcero, O.J.; Ryan, J.C. Becoming a knowledge economy: The case of Qatar, UAE, and 17 benchmark countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 8, 1146–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. What makes urban schools different? PISA Focus 2013, 28, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Felder, D.; Vuollo, M. Qatari Women in the Workforce; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR612.html (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Yahia, I.B.; Al-Emadi, M. Exploring the determinants of 2022 FIFA World Cup attendance in Qatar. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2018, 18, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkouti, I.M. Qatar’s Educational System in the Technology-Driven Era: Long Story Short. Int. J. High. Educ. 2016, 5, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghih, N.; Sarfaraz, L. Dynamics of innovation in Qatar and its transition to knowledge-based economy: Relative strengths and weaknesses. QSci. Connect 2014, 2014, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, S.B.J.; Abdelmoneim, A.; Cherif, A.; Moukarzel, D.; Daoud, K. Assessing general education learning outcomes at Qatar University. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2016, 8, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhananga, R.; Nawaz, W.; Batur, I.; Koç, M. Industry-University-Government Partnership (IUGP)—Trends, Drivers and Policy Recommendations for Qatar. In Proceedings of the ISPIM Innovation Symposium, Melbourne, Australia, 10–13 December 2017; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Abduljawad, H. Challenges in Cultivating Knowledge in University-Industry-Government Partnerships—Qatar as a Case Study. Res. Gate 2015, 105, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanu, M.; Kumar, S. A Study on Global Human Capital & Its Trends: How to Transform and Design Organiztions into High Performers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. IJHRMR 2017, 7, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pasban, M.; Nojedeh, S.H. A Review of the Role of Human Capital in the Organization. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 230, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, M.; Arokiasamy, L.; Ismail, M. Human capital development and its impact on firm performance: Evidence from developmental economics. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2009, 2, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, H.; Leu, F.-Y.; Chen, C.K.; Mohiddin, F. Managing Human Capital in Today’s Globalization: A Management Information System Perspective; Apple Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, V. Women entrepreneurship in Gulf Region: Challenges and strategies in GCC. Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag. 2019, 10, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.; Crotti, R.; Geiger, T.; Ratcheva, V. Global Gender Gap Report 2020; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, M. Women Empowerment and Economic Development-an Exploratory Study in Pakistan. J. Bus. Stud. Q. 2014, 5, 210–221. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, N.; Babar, Z.; Ewers, M.; Shaath, M. Gender and mobility: Qatar’s highly skilled female migrants in context. Migr. Dev. 2020, 9, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkowska, K.U. Arab women in the Gulf and the narrative of change: The case of Qatar. Int. Stud. Interdiscip. Polit. Cult. J. 2014, 16, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Thani, W.A.; Ari, I.; Koç, M. Education as a Critical Factor of Sustainability: Case Study in Qatar from the Teachers’ Development Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embley, D.W.; Thalheim, B. Handbook of Conceptual Modeling: Theory, Practice, and Research Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, J. Theory building through conceptual methods. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1993, 13, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. Conceptual modeling: Definition, purpose and benefits. In Proceedings of the 2015 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Huntington Beach, CA, USA, 6–9 December 2015; pp. 2812–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F. Sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and business models: Integrative framework and propositions for future research. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, S.; Rovenskaya, E.; Obersteiner, M.; Langan, S. Practice and perspectives in the validation of resource management models. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecours, A. Scientific, professional and experiential validation of the model of preventive behaviours at work: Protocol of a modified Delphi Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, M.M.; Sulaiman, N.L.; Sern, L.C.; Salleh, K.M. Measuring the validity and reliability of research instruments. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 204, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, B.J.; Evans, A.N. Methods in Psychological Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Knapik, M. The qualitative research interview: Participants’ responsive participation in knowledge making. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, V.; Leamy, M.; Tew, J.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Fit for purpose? Validation of a conceptual framework for personal recovery with current mental health consumers. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Mesa, J.; González-Chica, D.A.; Duquia, R.P.; Bonamigo, R.R.; Bastos, J.L. Sampling: How to select participants in my research study? An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Badrudin, B. The Effectiveness of Study Program Quality Improvement (A Case Study at Islamic Education Management Department, Faculty of Tarbiyah and Teacher Training). In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Educational, Management, Administration and Leadership, Bandung, West Java, Indonesia, 28 August 2016; pp. 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.X.; Zhang, L.J. Teacher learning in difficult times: Examining foreign language teachers’ cognitions about online teaching to tide over COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albantani, A.M.; Madkur, A. Teaching Arabic in the era of Industrial Revolution 4.0 in Indonesia: Challenges and opportunities. ASEAN J. Commun. Engagem. 2019, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Gani, N.I.; Rathakrishnan, M.; Krishnasamy, H.N. A pilot test for establishing validity and reliability of qualitative interview in the blended learning English proficiency course. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 140–143. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-PILOT-TEST-FOR-ESTABLISHING-VALIDITY-AND-OF-IN-Gani-Rathakrishnan/692dab005bb47477f3fa733fe8da0bff3e1f599f (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Said, Z. 21st Century Skills’ Challenges to Postsecondary Tvet Institutions in Qatar. Research Gate. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349297153_21ST_CENTURY_SKILLS%27_CHALLENGES_TO_POSTSECONDARY_TVET_INSTITUTIONS_IN_QATAR (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Maclean, R.; Fien, J. Introduction and overview: TVET in the Middle East—Issues, concerns and prospects. Int. J. Train. Res. 2017, 15, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hassen, T. Ben Entrepreneurship, ICT and Innovation: State of Qatar Transformation to a Knowledge-Based Economy; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335812270_Entrepreneurship_ICT_and_innovation_state_of_Qatar_transformation_to_a_knowledge-based_economy (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Weber, A.S. Education, development and sustainability in Qatar: A case study of economic and knowledge transformation in the Arabian Gulf. In Education for a Knowledge Society in Arabian Gulf Countries; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creel, B.; Nite, S.; Almarri, J.E.; Shafik, Z.; Mari, S.; Al-Thani, W.A. Inspiring Interest in STEM Education Among Qatar’s Youth. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE International Forum, Columbus, OH, USA, 28 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sellami, A. A Critical Review of Research on STEM Education in Qatar. Int. J. Hum. Educ. 2021, 20, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncada-Paternò-Castello, P.; Dosso, M.; Gkotsis, P.; Hervas, F. Industrial Research and Innovation: Evidence for Policy. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308889631_Industrial_Research_and_Innovation_Evidence_for_Policy (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Ilie, C.; Monfort, A.; Fornes, G.; Cardoza, G. Promoting Female Entrepreneurship: The Impact of Gender Gap Beliefs and Perceptions. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211018468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrez, A. Investigating critical obstacles to entrepreneurship in emerging economies: A comparative study between males and females in Qatar. Acad. Entrep. J. 2019, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansari, H. Women Are Key to Developing a Knowledge-based Economy in Qatar. Gulf Aff. Spring 2018, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Los Rios-Carmenado, D.; Ortuño, M.; Rivera, M. Others Private—Public partnership as a tool to promote entrepreneurship for sustainable development: WWP torrearte experience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitjar, R.D.; Timmermans, B. Knowledge bases and relatedness: A study of labour mobility in Norwegian regions. In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems-Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 149–171. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo, L.; Lebrato, J.; Garvi, D.; Jigena, B.; Muñoz Pérez, J.J. Others Naturalization: A new concept developed and carried out in the subject “Environmental Technology” of degree in Industrial Engineering. In Proceedings of the 10th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED), Valencia, Spain, 7–9 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. Employment effects of trade in intermediate and final goods: An empirical assessment. Int. Labour Rev. 2015, 154, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uprety, D. The impact of international trade on migration by skill levels and gender in developing countries. Int. Migr. 2020, 58, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.K.; Kunze, A. The Demand for High-Skilled Workers and Immigration Policy; Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, A. Migration Policy in an Integrating Europe. 2001. Available online: http://aei.pitt.edu/2086/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Gremm, J.; Barth, J.; Fietkiewicz, K.J.; Stock, W.G. Transitioning towards a knowledge society. In Qatar as a Case Study; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhulaifi, A. Government Expenditure and Economic Growth in Qatar: A Time Series Analysis. Research Gate. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/287865670_Government_expenditure_and_economic_growth_in_Qatar_A_time_series_analysis (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Richer, R.A. Sustainable development in Qatar: Challenges and opportunities. QSci. Connect 2014, 2014, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeckel, K. Costs and Benefits in Vocational Education and Training. Organ. Econ. Coop. Dev. 2008, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wonacott, M.E. Benefits of Vocational Education. Myths and Realities, No. 8; ED441179; Columbus ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult Career and Vocational Education, Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 2000. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED441179 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Brunello, G.; Rocco, L. The labor market effects of academic and vocational education over the life cycle: Evidence based on a British Cohort. J. Hum. Cap. 2017, 11, 106–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, F. Making the transition to a ‘knowledge economy’and ‘knowledge society’: Exploring the challenges for Saudi Arabia. In Education for a Knowledge Society in Arabian Gulf Countries; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, G.N.; Sellen, D.B. Light-Scattering Raleigh Linewidth Measurements on G-Actin. Biochem. J. 1971, 125, 104–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, N.M.; Townsend, S.S.M. How can financial incentives improve the success of disadvantaged college students: Insights from the social sciences. In Decision Making for Student Success: Behavioral Insights to Improve College Access and Persistence; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Grecu, V.; Denes, C. Benefits of entrepreneurship education and training for engineering students. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 121, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumuti, D.W.; Wanderi, P.M.; Lang’at-Thoruwa, C. Benefits of university-industry partnerships: The case of Kenyatta University and Equity Bank. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Krahmer, F.; Schmoch, U. Science-based technologies: University–industry interactions in four fields. Res. Policy 1998, 27, 835–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigge, G.W. University—Industry partnerships: What do they mean to universities? A review of the literature. Ind. High. Educ. 2005, 19, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Promoting Entrepreneurship and Innovative SMEs in a Global Economy. In Proceedings of the 2nd OECD Ministerial Conference on SMEs, Istanbul, Turkey, 3–5 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bommes, M.; Geddes, A. Immigration and Welfare: Challenging the Borders of the Welfare State; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mclaughlan, G.; Salt, J. Migration Policies towards Highly Skilled Foreign Workers: Report to the Home Office; Research Development and Statistics Directorate, Home Office: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Qin, L.; Wang, X.; Rao, X. Teaching Reform Exploring of Vocational Education Courses with the Guidance of “Military Training and Competition”. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Humanities Science, Management and Education Technology (HSMET 2019), Singapore, 21–23 June 2019; Atlantis Press: Singapore; pp. 532–538. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, R.T. Military Entrepreneurs and the Spanish Contractor State in the Eighteenth Century; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Respondent | Gender | Age | Qatari | Profession | Education | Current Sector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR1 | F | 30s | YES | Engineer | Master | Private |

| IR2 | M | 50s | YES | University President | Ph.D. | Education |

| IR3 | F | 40s | YES | Director | Ph.D. | Education and Research |

| IR4 | M | 40s | YES | CEO | Ph.D. | Education |

| IR5 | F | 50s | YES | Assistant Undersecretary | Master | Education |

| IR6 | F | 30s | NO | Manager | Master | Private |

| IR7 | M | 40s | YES | Director | Ph.D. | Private |

| IR8 | F | 50s | YES | CEO | Master | Education |

| IR9 | M | 40s | NO | Manager | Ph.D. | Military |

| IR10 | M | 30s | YES | Planning and Quality Manager | Bachelor | Public |

| IR11 | M | 50s | NO | Quality Manager | Ph.D. | Public |

| IR12 | M | 50s | NO | Economic consultant | Ph.D. | Public |

| IR13 | F | 30s | YES | Engineer | Ph.D. | Private |

| IR14 | M | 30s | YES | Quality and Planning | Master | Public |

| IR15 | M | 50s | NO | Military Rank | Ph.D. | Military |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamed, B.H.; Ari, I.; Al-Sada, M.b.S.; Koç, M. Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413750

Mohamed BH, Ari I, Al-Sada MbS, Koç M. Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413750

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamed, Btool H., Ibrahim Ari, Mohammed bin Saleh Al-Sada, and Muammer Koç. 2021. "Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413750

APA StyleMohamed, B. H., Ari, I., Al-Sada, M. b. S., & Koç, M. (2021). Strategizing Human Development for a Country in Transition from a Resource-Based to a Knowledge-Based Economy. Sustainability, 13(24), 13750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413750