Work Tenure and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors; A Study in Ghanaian Technical Universities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

Social Exchange Theory, OCBs, Tenure, and LMX

3. Literature Review

3.1. OCB

3.2. Leader–Member Exchange

3.3. Work Tenure

3.4. Organizational Tenure

4. Methods

Measures

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atatsi, E.; Stoffers, J.; Kil, A. Factors affecting employee performance: A systematic literature review. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Age, work experience, and the psychological contract. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Affective organizational commitment and citizenship behavior: Linear and non-linear moderating effects of organizational tenure. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Does longer tenure help or hinder job performance? J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: It’s construct clean-up time. Hum. Perf. 1997, 10, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle, E.; Kumassey, A.S. The moderating role of organizational tenure in the relationship between organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior: Empirical evidence from the Ghanaian Banking industry. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dirican, A.; Erdil, O. An exploration of academic staff’s organisational citizenship behavior and counter work behaviour in relation to demographic characteristics. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegans, L.; McCambey, R.B.; Hammond, H. Organizational citizenship behavior and work experience. Hosp. Top. 2012, 90, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, U.J. Work experience and organizational citizenship behavior: A study of the telecom sector in India. Int. J. Manag. IT Eng. 2019, 9, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y. The benefits of organizational citizenship behavior for job performance and the moderating role of human capital. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafidz, S.W.M.; Hoesini, S.M.; Fatimah, O. The relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counter work behavior. Asian Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Organizational tenure and job performance. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 1220–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagger, J.; Fontaine, F.; Postel-Vinay, F.; Robin, J.M. Tenure, Experience, Human Capital and Wages: A Tractable Equilibrium Search Model. of Wage Dynamics; Working Paper No. CWP12/14; Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice (CEMMAP): London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital and organizational advantage. Acad Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H.; Bloodgood, J.M. Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Acad Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Choi, Y.; Rhee, S.-Y.; Moon, T.W. Social capital and organizational citizenship behavior. Double mechanism of emotional regulation and job engagement. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, A.; Armstrong, M. Out of the box. People Manag. 1998, 23, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppila, O. So what am I supposed to do? A multi-level examination of role clarity. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 51, 737–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.A.; Bodner, T.; Erdogan, B.; Truxillo, D.M.; Tucker, J.S. Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 707–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, M.; Rangnekar, S. Role clarity and organizational citizenship behaviour: Does tenure matter? A study on Indian power sector. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 207S–224S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, G. Understanding the relationship among leadership effectiveness, leader-member interactions and organizational citizenship behavior in higher institutions of learning in Ghana. J. Int. Educ. Res. 2012, 8, 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Power, R.L. Leader-member theory in higher and distance education. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2013, 14, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolcott, A.M.; Bowdon, M.A. Leader-member exchange (LMX) and higher education leadership: A relationship building tool for departmental chairs. J. Excel. Coll. Teach. 2017, 28, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Woldegiorgis, E.T.; Doevenspeck, M. The changing role of higher education in Africa: A historical reflection. High. Educ. Stud. 2013, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B. The dual roles of higher education institutions in the knowledge economy. In Globalization and Change in Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Olssen, M.; Peters, M.A. Neoliberalism, higher education and the knowledge economy: From the free market to knowledge capitalism. J. Educ. Policy 2005, 20, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benneh, G. Research management in Africa. High. Educ. Policy 2002, 15, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boohene, R.; Agyapong, D. Centre for Entrepreneurship and Small Enterprises Development. In Entrepreneurship Centres; Maas, G., Jones, P., Eds.; University of Cape Coast: Cape Coast, Ghana, 2017; pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Curnalia, R.M.L.; Mermer, D. Renewing our commitment to tenure, academic freedom, and shared governance to navigate challenges in higher education. Rev. Commun. 2018, 18, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, D.-W.; Kenney, M. Universities, clusters, and innovation systems: The case of Seoul, Korea. World Dev. 2007, 35, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P.G. Globalization and the University: Realities in an unequal world. In International Handbook of Higher Education; Forest, J.J.F., Altbach, P.G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Atuahene, F. Rethinking the missing mission of higher education: An anatomy of the research challenge of African Universities. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2011, 46, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Bhargava, S. Effects of psychological contract breach on organizational outcomes: Moderating role of tenure and educational Levels. Vikalpa 2013, 38, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S.; Shukla, A. The influence of leader-member exchange relations on employee engagement and work role performance. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2013, 16, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyekye, S.A.; Haybatollahi, M. Organizational citizenship behaviour: An empirical investigation of the impact of age and job satisfaction on Ghanaian industrial workers. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucanok, B. The effects of work values, work value congruence and centrality on organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Behav. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffers, J.M.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Notelaers, G.L.A. Towardsl a moderated mediation model of innovative work behaviour enhancement. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2014, 27, 642–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffers, J.M.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Schrijver, I. Towards a sustainable model of innovative work behaviors’ enhancement: The mediating role of employability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, P.; Bidarian, S. The relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 47, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.; Malik, F.M. My leader’s group is my group. Leader member exchange and employees’ behaviours. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2017, 29, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesluk, P.E.; Jacobs, R.R. Toward an integrated model of work experience. Pers. Psychol. 1998, 51, 321–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birasnav, M.; Rangnekar, S. Structure of human capital enhancing human resource management practices in India. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Decramer, A.; Smolders, C.; Vanderstraeten, A. Employee performance management culture and system features in higher education: Relationship with employee performance management satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 352–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Bonett, D.G. The moderating effects of employee tenure on the relation between organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnipseed, D.; Murkison, G. Good soldiers and their syndrome: Organizational citizenship behavior and the work environment. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2000, 2, 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational citizenship behavior: Recent trends and developments. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prottas, D.J.; Shea-Von Fossen, R.J.; Cleaver, C.M.; Andreassi, J.K. Relationships among faculty perceptions of the tenure process and their commitment and their engagement. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2017, 9, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatough, E.M.; Chang, C.; Miloslavic, S.A.; Johnson, R.E. Relationships of role stressors with organisational citizenship behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W.; Ryan, K. A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, B.C. Perceived organizational climate and organizational tenure on organizational citizenship behavior: An empirical study among Ghanaian banks. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, L.M.; Bommer, W.H.; Rao, A.N.; Seo, J. Social and economic exchange in the employment-organization relationship: The moderating role of reciprocation wariness. J. Manag. Psychol. 2009, 24, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Emmerik, H.; Sanders, K. Social embeddedness and job performance of tenured and untenured professionals. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2004, 41, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebohn, J.H.; Bommer, W.H.; Liden, R.C.; Brouer, R.; Ferris, G.R. Consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 1715–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, P.; Lawrence, B.S.; Bentler, P.M. The influence of social and work exchange relationships on organizational citizenship behavior. Group Organ. Manag. 2004, 29, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Bukhari, I.; Adil, A. Moderating role of psychological capital between perceived organizational support and organizational citizenship behavior and its dimensions. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2016, 5, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, S.A.; Ang, S.; Boh, W.F. Firm-specific human capital and compensation-organizational tenure profiles: An archival analysis of salary data for IT professionals. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 46, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Xie, J. Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of identification with leader and leader’s reputation. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2014, 42, 1699–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Leader-member exchange and citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsari, C.; Stoffers, J.; Gunawan, A. The influence of generational diversity management and leader–member exchange on innovative work behaviors mediated by employee engagement. J. Asia-Pac. Bus. 2019, 20, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karriker, J.H.; Williams, M.L. Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior: A moderated -mediated model. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Cooper, B.; Sendjaya, S. How servant leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of LMX, empowerment, and proactive personality. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J.K.; Bawole, J.N. Testing the mediation effect of person-organisation fit on the relationship between talent management and talented employees’ attitudes. Int. J. Manpow. 2018, 39, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darto, M.; Setyadi, D.; Riadi, S.S.; Hariyadi, S. The effect of transformational leadership, religiosity, job satisfaction, and organizational culture on organizational citizenship behavior and employee performance in the regional offices of national institute of public administration, Republic of Indonesia. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 7, 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, F.C.; Liang, J.; Ashford, S.J.; Lee, C. Job insecurity and organizational citizenship behavior: Exploring curvilinear and moderated relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwomoh, G.; Gyamfi, L.A.; Luguterah, A.W. Effect of organizational citizenship behavior on performance of employees of Kumasi Technical University: Moderating role of work overload. J. Manag. Econ. Stud. 2019, 1, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Toga, R.; Khayundi, D.A.; Mjoli, T.Q. The impact of organizational commitment and demographic variables on organisational citizenship behaviour. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 643–650. [Google Scholar]

- Eyupoglu, S.Z. The organizational citizenship behavior of academic staff in North Cyprus. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Paine, J.; Bachrach, D. Organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Martin, R.; Epitropaki, O.; Mankad, A.; Svensson, A.; Weeden, K.C. Effective leadership in salient groups: Revisiting leader-exchange theory from the perspective of social identity theory of leadership. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 991–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Sears, G.; Zhang, H. Revisiting the “give and take” in LMX: Exploring equity sensitivity as a moderator of the influence of LMX on affiliative and change -oriented OCB. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 555–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Green, S.A. The effects of leader-member exchange on employee citizenship and impression management behaviour. Hum. Relat. 1993, 46, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Maslyn, J.M. Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. J. Manag. 1998, 24, 43–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansereau, F.; Graen, G.; Haga, W. A vertical dyad approach to leadership within formal organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perf. 1975, 13, 46–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Maslyn, J.M. Reciprocity in manager-subordinate relationship: Components, configurations, and outcomes. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Scandura, T.A. Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Res. Organ. Behav. 1987, 9, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.Y.; Chow, I.H.S.; Chiu, R.K.; Pan, W. Outcome favorability in the link between leader–member exchange and organizational citizenship behavior: Procedural fairness climate matters. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inelmen, K.; Selekler-Goksen, N.; Yildirim-Öktem, Ö. Understanding citizenship behaviour of academics in American- vs Continental European-modeled universities in Turkey. Pers. Rev. 2017, 46, 1142–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, M.A.; Schmidt, F.L.; Hunter, J.E. Job experience correlates of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1988, 73, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, N.K.; Shemla, M.; Wegge, J.; Diestel, S. Organizational tenure and employee performance: A multilevel analysis. Group Organ. Manag. 2014, 39, 664–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.N.; McDaniel, M.A. The stability of validity coefficients over time: Ackerman’s (1988) model and the general aptitude test battery. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T.A.; Cable, D.M.; Boudreau, J.W.; Bretz, R.D. An empirical investigation of the predictors of executive career success. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 485–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman, M.C. Searching for the inverted u-shaped relationship between time and performance: Meta-analyses of the experience/performance, tenure/performance, and age/performance relationships. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 609–640. [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Avey, J.B.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnrue, M.P. Length of experience and the performance of managers in the establishment phase of their careers. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J.A., III; Ferris, G.R.; Fandt, P.M.; Wayne, S.J. The organizational tenure-Job involvement relationship: A job-career experience explanation. J. Organ. Behav. 1987, 8, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. The effects of relative organizational tenure on job performance in the public sector. Public Pers. Manag. 2018, 47, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.H.; Posner, B.Z. Managerial Values in Perspective; AMA Membership Publications Division, American Management Associations: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Brockner, J. The effects of work layoffs on survivors: Research, theory and practice. Res. Organ. Behav. 1988, 10, 213–255. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, J.; Zhao, J. Research in organizational citizenship continuum and its consequences. Front. Bus. Res. China 2011, 5, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornbill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 6th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Lam, S.S.; Feldman, D.C. Organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior: Do males and females differ? J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 93, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waismel-Manor, R.; Tzimer, A.; Berger, E.; Dikstein, E. Two of a kind? Leader-member exchange and organizational citizenship behavior. The moderating role of leader-member similarity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 40, 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Vidyarthi, P.R.; Liden, R.C.; Anand, S.; Erdogan, B.; Ghosh, S. Where do I stand? Examining the effects of leader-member exchange social comparison in employee work behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Ngo, H.; Zhang, L.; Lau, V.P. The interaction between leader-member exchange and perceived job security in predicting employee altruism and work performance. J. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 84, 669–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahony, D.M.; Klimchak, M.; Morrel, D.L. The portability of career-long work experience. Propensity to trust as a substitute for valuable work experience. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Chowdhury, S.; Van de Voort, D. Firm productivity moderated link between human capital and compensation: The significance of task-specific human capital. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffers, J.M.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M. An innovative work behaviour-enhancing employability model moderated by age. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2018, 42, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.L.; Rush, M.C. Altruistic organizational citizenship behavior: Context, disposition and age. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 140, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T.; Sajilan, S. Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 4, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.80 | 0.40 | – | |||||

| 2. Age | 2.08 | 0.86 | 0.077 | – | ||||

| 3. Education level | 4.35 | 1.79 | −0.045 | 0.038 | – | |||

| 4. LMX | 0 | 1.00 | 0.031 | 0.055 | 0.105 * | – | ||

| 5. Work tenure | 13.78 | 7.75 | −0.005 | 0.705 *** | −0.003 | 0.049 | – | |

| 6. Organizational tenure | 9.73 | 5.82 | −0.029 | 0.558 *** | 0.067 | 0.035 | 0.651 *** | – |

| 7. OCB | 0 | 1.00 | 0.052 | 0.080 | 0.101 * | 0.271 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.147 ** |

| Model 1 (Control Variables and Main Effects) | Model 2 (Quadratic Effects Included) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 0.01 | −0.004 |

| 2. Age | −0.15 * | −0.15 * |

| 3. Education | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| 4. LMX | 0.25 *** | 0.26 *** |

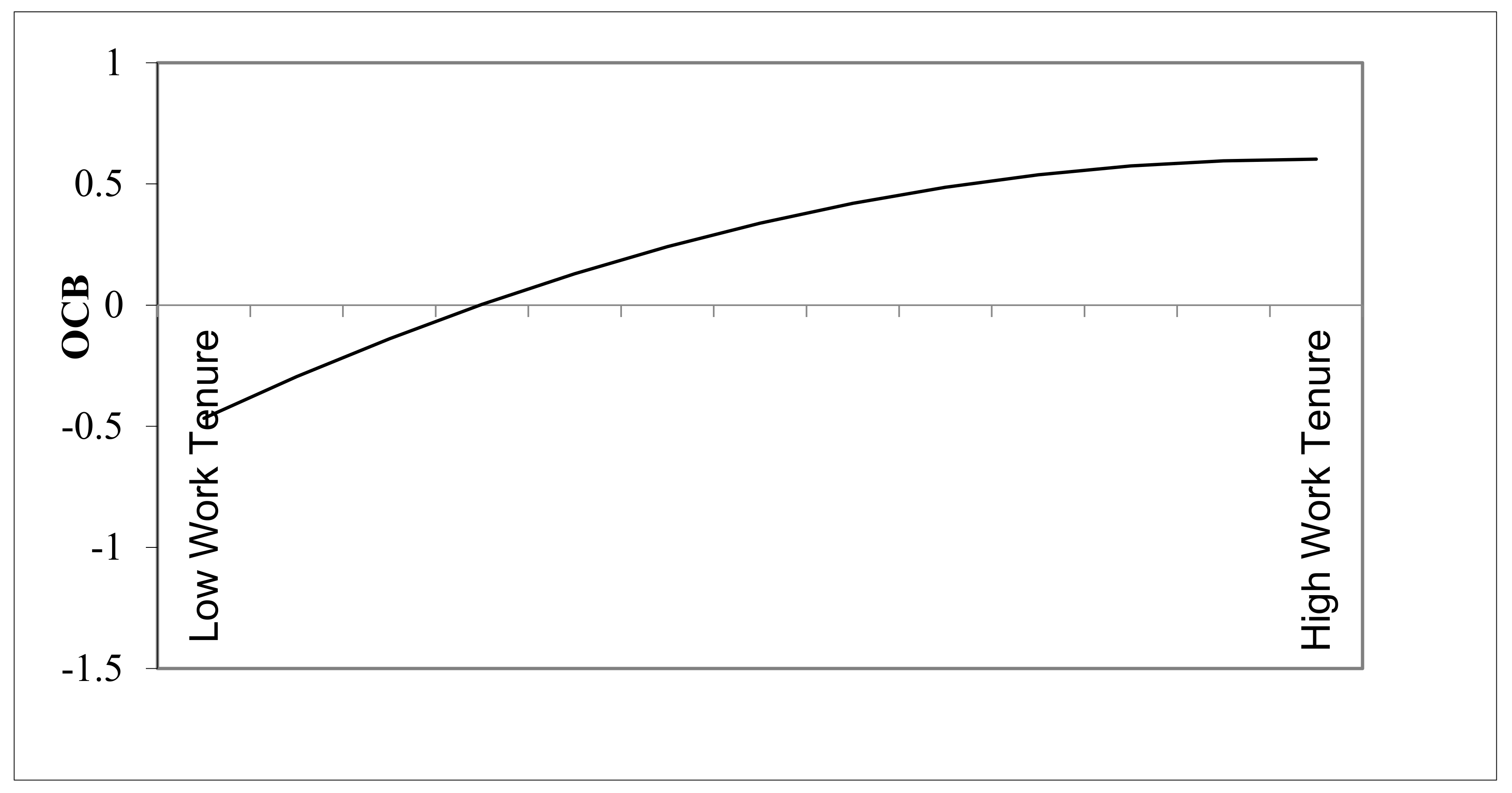

| 5. Work tenure | 0.25 ** | 0.39 *** |

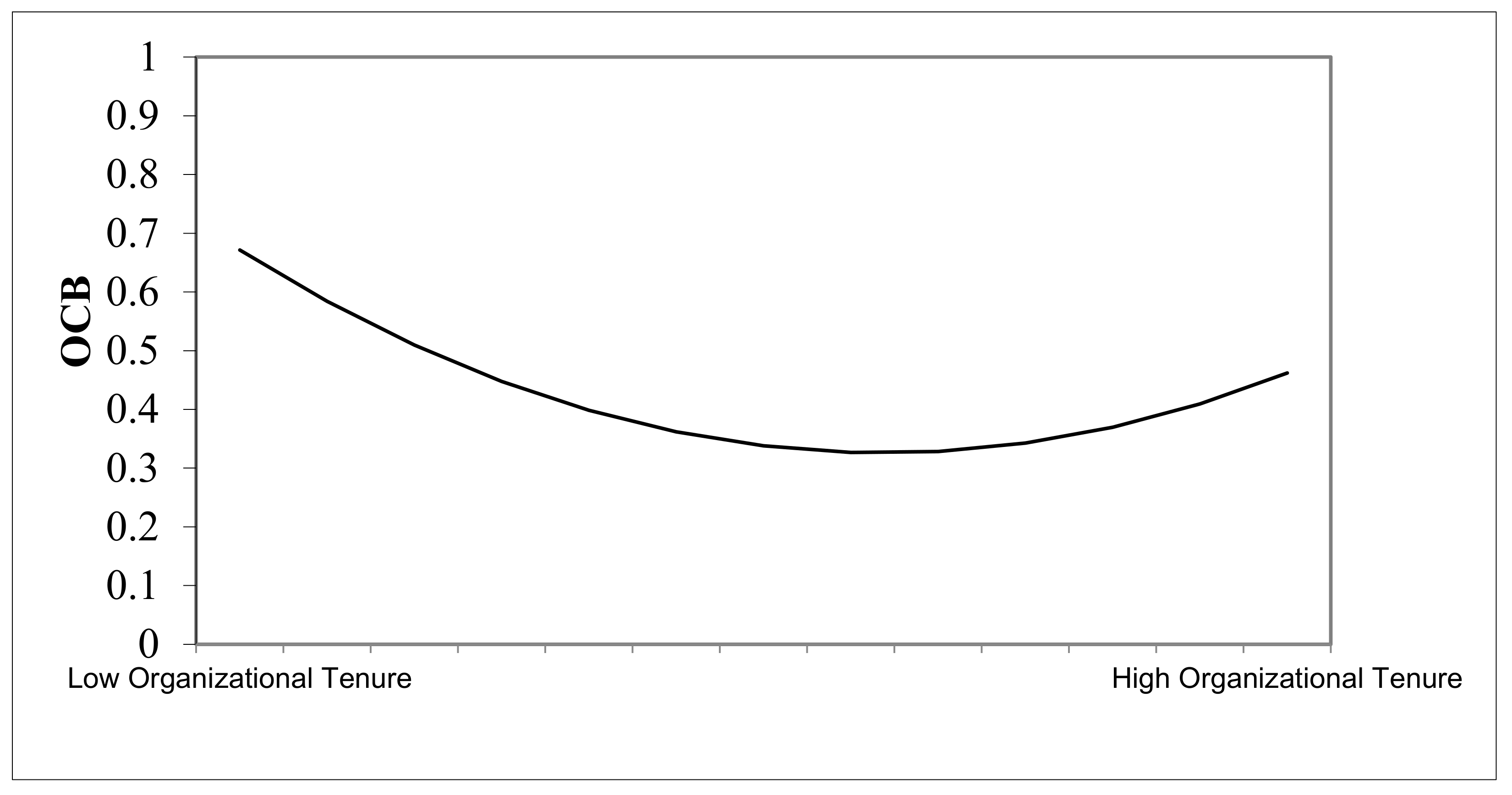

| 6. Organizational tenure | 0.07 | −0.08 |

| 7. Work tenure 2 | −0.23 ** | |

| 8. Organization tenure 2 | 0.17 † | |

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| F change | 7.58 *** | 3.79 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atatsi, E.A.; Stoffers, J.; Kil, A. Work Tenure and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors; A Study in Ghanaian Technical Universities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413762

Atatsi EA, Stoffers J, Kil A. Work Tenure and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors; A Study in Ghanaian Technical Universities. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413762

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtatsi, Eli Ayawo, Jol Stoffers, and Ad Kil. 2021. "Work Tenure and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors; A Study in Ghanaian Technical Universities" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413762

APA StyleAtatsi, E. A., Stoffers, J., & Kil, A. (2021). Work Tenure and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors; A Study in Ghanaian Technical Universities. Sustainability, 13(24), 13762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413762