Knowledge Management in Relation to Innovation and Its Effect on the Sustainability of Mexican Tourism Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

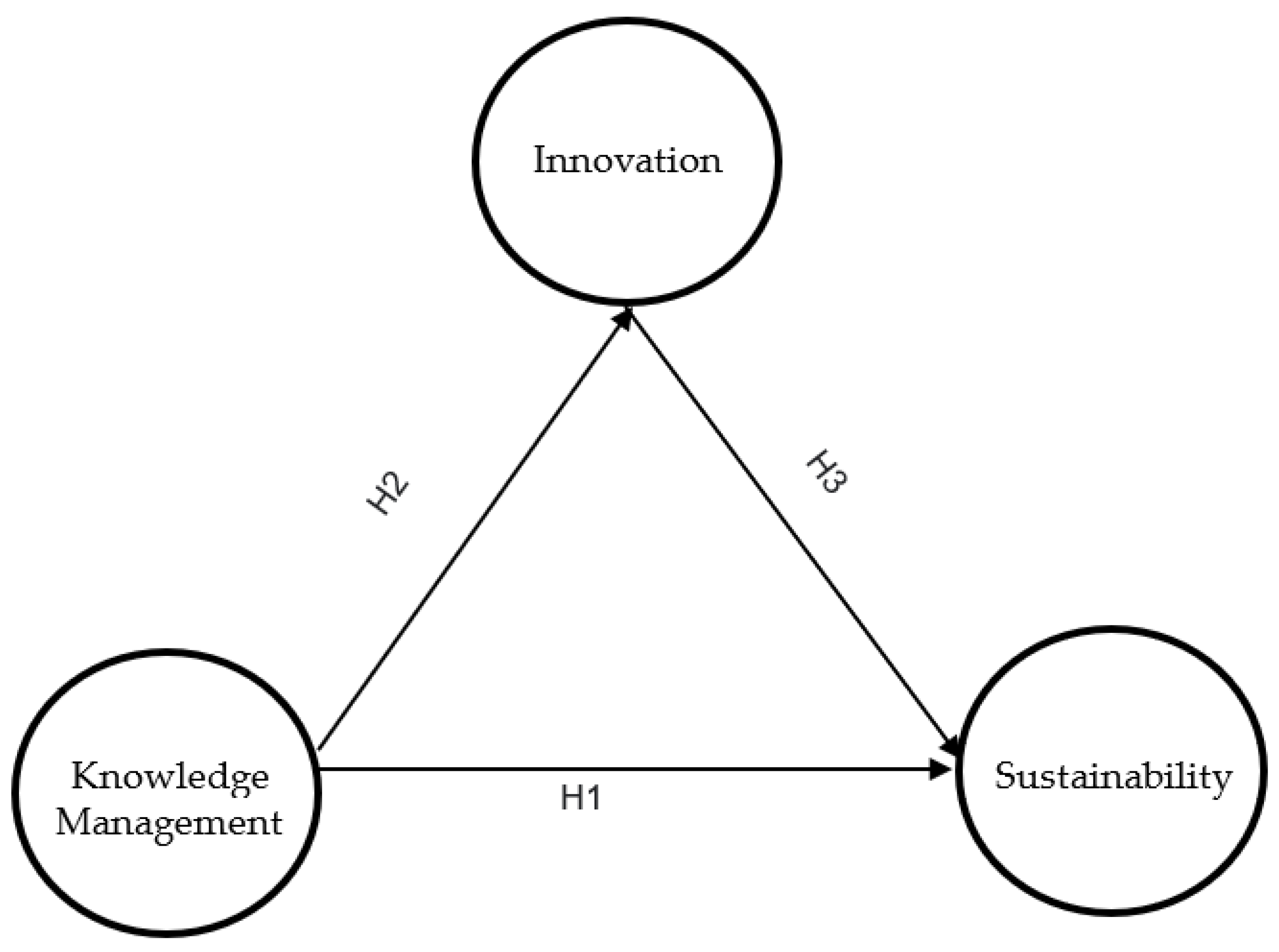

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Knowledge Management and Sustainability

2.2. Knowledge Management and Innovation

2.3. Innovation and Sustainability

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Questionnaire

3.2. Construct Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Collinearity

4.2. Coefficient of Determination (R²) and R² Adjusted

4.3. The Test of Q² (Stone–Geisser)

4.4. Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR)

4.5. Effect Size (f²)

4.6. Structural Model and Hypothesis Test

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyck, B.; Silvestre, B.S. Enhancing socio-ecological value creation through sustainable innovation 2.0: Moving away from maximizing financial value capture. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1593–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable for Implications Development and Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.W.B.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Knowledge management in the context of sustainability: Literature review and opportunities for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Secretary-General. World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future (‘The Brundtland Report’); UN: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks—Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Ltd.: Mankato, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, G.D. Knowledge management in organizations: Examining the interaction between technologies, techniques, and people. J. Knowl. Manag. 2001, 5, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holsapple, C.W.; Joshi, K.D. An investigation of factors that influence the management of knowledge in organizations. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 235–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Stankosky, M.; Mohamed, M. An empirical assessment of knowledge management criticality for sustainable development. J. Knowl. Manag. 2009, 13, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, M.; El-Diraby, T.E. The functions of knowledge management processes in urban impact assessment: The case of Ontario. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2018, 36, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herciu, M.; Ogrean, C.; Belascu, L. A Behavioral Model of Management—Synergy between Triple Bottom Line and Knowledge Management. World J. Soc. Sci. 1998, 1, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, M. The role of knowledge management in innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2007, 11, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darroux, C.; Jonathan, H.; Massele, J.; Thibeli, M. Knowledge Management the Pillar for Innovation and Sustainability. Int. J. Sci. Basic Appl. Res. (IJSBAR) 2013, 9, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- López-Nicolás, C.; Meroño-Cerdán, Á.L. Strategic knowledge management, innovation and performance. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2011, 31, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.L.; Hsu, M.S.; Lin, F.J.; Chen, Y.M.; Lin, Y.H. The effects of industry cluster knowledge management on innovation performance. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneipp, J.M.; Gomes, C.M.; Bichueti, R.S.; Frizzo, K.; Perlin, A.P. Sustainable innovation practices and their relationship with the performance of industrial companies. Rev. Gestão 2019, 26, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nidumolu, R.; Prahalad, C.K.; Rangaswami, M.R. Why sustainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Lo, M.F.; Ng, A.W. Knowledge Management and Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, D.B.; Köhler, T.; Weith, T. Knowledge management in sustainability research projects: Concepts, effective models, and examples in a multi-stakeholder environment. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2016, 15, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangler, W.; Sroufe, R.; Madia, M.; Singadivakkam, J. Sustainability-focused knowledge management in a global enterprise. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2014, 55, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheate, W.R.; Partidário, M.R. Strategic approaches and assessment techniques-Potential for knowledge brokerage towards sustainability. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2010, 30, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Sağsan, M. Impact of knowledge management practices on green innovation and corporate sustainable development: A structural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, J.A.; Olsen, B. Knowledge management and sustainable competitive advantages: The impact of dynamic contextual training. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2003, 23, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloet, M.; Samson, D. Knowledge and Innovation Management to Support Supply Chain Innovation and Sustainability Practices. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J.C.F.; Severo, E.A.; de Vasconcelos, C.R.M. The influence of entrepreneurial, market, knowledge management orientations on cleaner production and the sustainable competitive advantage. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliuniene, J.; Tvaronavičiene, M.; Blažyte, M. Knowledge management practice in general education schools as a tool for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Kundu, A. Linkage between business sustainability and tacit knowledge management in MSMEs: A case-based study. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2020, 50, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Torres, G.C.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Maldonado-Guzmán, G.; Kumar, V.; Rocha-Lona, L.; Cherrafi, A. Knowledge management for sustainability in operations. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmohammadi, C.; Sofiyabadi, J.; Kolahi, B. How do knowledge management practices affect sustainable balanced performance? Mediating role of innovation practices. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ruhanen, L. Progressing the sustainability debate: A knowledge management approach to sustainable tourism planning. Curr. Issues Tour. 2008, 11, 429–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B.; Chadee, D. Knowledge management view of environmental sustainability in manufacturing SMEs in the Philippines. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2016, 14, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalić, M.; Nikolić, M.; Radosav, D.; Stanisavljev, S.; Pečujlija, M. Influencing factors on knowledge management for organizational sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Budur, T.; Omer, H.M.; Heshmati, A. Links between knowledge management and organisational sustainability: Does the ISO 9001 certification have an effect? Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.S.; Anumba, C.J.; Carrillo, P.M.; Al-Ghassani, A.M. STEPS: A knowledge management maturity roadmap for corporate sustainability. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2006, 12, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardoni, A.; Zanin, F.; Corazza, G.; Paradisi, A. Knowledge management and performance measurement systems for SMEs’ economic sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kordab, M.; Raudeliūnienė, J.; Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I. Mediating role of knowledge management in the relationship between organizational learning and sustainable organizational performance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.K.; Tseng, M.L.; Tan, K.H.; Bui, T.D. Knowledge management in sustainable supply chain management: Improving performance through an interpretive structural modelling approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Implementation of Sustainability Management and Company Size: A Knowledge-Based View. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrkar, A. the Investigation of the Role of Information Technology in Creating and Developing a Sustainable Competitive Advantage for Organizations Through the Implementation of Knowledge Management. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 8, 287–299. [Google Scholar]

- Uniyal, S.; Mangla, S.K.; Sarma, P.R.S.; Tseng, M.L.; Patil, P. ICT as “Knowledge management” for assessing sustainable consumption and production in supply chains. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 164–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, A. How does knowledge management influence innovation and competitiveness? J. Knowl. Manag. 2000, 4, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darroch, J. Knowledge management, innovation and firm performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2005, 9, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, J.W. Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumyaja, D.; Sowmya, C.S. Knowledge management and innovation performance in knowledge intensive organisations—The role of HR practices. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2020, 11, 370–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U.; Islam, T. Exploring the influence of knowledge management process on corporate sustainable performance through green innovation. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2079–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donate, M.J.; Sánchez de Pablo, J.D. The role of knowledge-oriented leadership in knowledge management practices and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbu, C.O. Managing knowledge and intellectual capital for improved organizational innovations in the construction industry: An examination of critical success factors. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2004, 11, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, S.; Rodríguez, M.Á.; García-Castro, R.; Ariño, M.Á. Does stakeholder engagement promote sustainable innovation orientation? Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 111, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Lopez, J.G.; Ochoa Jiménez, S.; Jacobo Hernández, C.A. Knowledge management and innovation in agricultural organizations: An empirical study in the rural sector of northwest Mexico. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2020, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, A.; Giachino, C.; Ciampi, F.; Couturier, J. R&D internationalization in medium-sized firms: The moderating role of knowledge management in enhancing innovation performances. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Prado, J.C.; Navarrete, J.F.F.; Tafur-Mendoza, A.A. Relationship between condition of knowledge management and innovation capability in new technology-based firms. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, K.; Senin, A.A. The impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation: An empirical study. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noruzy, A.; Dalfard, V.M.; Azhdari, B.; Nazari-Shirkouhi, S.; Rezazadeh, A. Relations between transformational leadership, organizational learning, knowledge management, organizational innovation, and organizational performance: An empirical investigation of manufacturing firms. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 64, 1073–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, A. The effects of innovation by inter-organizational knowledge management. Inf. Dev. 2016, 32, 1402–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardeazabal, A.; Lunt, T.; Jahn, M.M.; Verhulst, N.; Hellin, J.; Govaerts, B. Knowledge management for innovation in agri-food systems: A conceptual framework. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hussain, I.; Akram, S.; Afaq, A.; Shad, M.A. Sustainable innovation in small medium enterprises: The impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation through a mediation analysis by using SEM approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acosta-Prado, J.C.; López-Montoya, O.H.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C.; Vázquez-Martínez, U.J. Sustainable Orientation of Management Capability and Innovative Performance: The Mediating Effect of Knowledge Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohamad, A.A.; Ramayah, T.; Lo, M.C. Sustainable knowledge management and firm innovativeness: The contingent role of innovative culture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Brouwers, H.E.J. Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payán-Sánchez, B.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Plaza-úbeda, J.A.; Vazquez-Brust, D.; Yakovleva, N.; Pérez-Valls, M. Open innovation for sustainability or not: Literature reviews of global research trends. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaurasia, S.S.; Kaul, N.; Yadav, B.; Shukla, D. Open innovation for sustainability through creating shared value-role of knowledge management system, openness and organizational structure. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2491–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfawaire, F.; Atan, T. The effect of strategic human resource and knowledge management on sustainable competitive advantages at Jordanian universities: The mediating role of organizational innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.M.; Scavarda, A.; Hofmeister, L.F.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Vaccaro, G.L.R. An analysis of the interplay between organizational sustainability, knowledge management, and open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Pezzi, A.; Kalisz, D.E. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S.; Haleem, A.; Luthra, S.; Mannan, B. Evaluating critical factors to implement sustainable oriented innovation practices: An analysis of micro, small, and medium manufacturing enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Yen, P.; Agarwal, R.; Arshinder, K.; Bajada, C. Collaborative innovation and sustainability in the food supply chain- evidence from farmer producer organisations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loučanová, E.; Šupín, M.; Čorejová, T.; Repková-Štofková, K.; Šupínová, M.; Štofková, Z.; Olšiaková, M. Sustainability and branding: An integrated perspective of eco-innovation and brand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Analyzing the green innovation practices based on sustainability performance indicators: A Chinese manufacturing industry case. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 1181–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braßler, M.; Schultze, M. Students’ innovation in education for sustainable development—A longitudinal study on interdisciplinary vs. Monodisciplinary learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.P.; Spieth, P.; Heidenreich, S. Facilitating business model innovation: The influence of sustainability and the mediating role of strategic orientations. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2021, 38, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Montalvo, C.; Quist, J.; Wagner, M. Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business cases for sustainability: The role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation and sustainable business models. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas (DENUE). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/mapa/denue/default.aspx (accessed on 31 May 2019).

- Bernal, C.; Turriago, Á.; Sierra, H. Aproximación a la medición de la gestión del conocimiento empresarial. Ad Minist. 2010, 16, 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Oslo Manual, 3rd ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2007; ISBN 9789264065659. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, G. El Sector Empresarial en la Sostenibilidad Ambiental: Ejes de Interacción; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- International Business Machines. IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS); International Business Machines: Endicott, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS (3.3.2); SmartPLS GmbH: Ismaning, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Ávila, M.; Fierro Moreno, E. Aplicación de la técnica PLS-SEM en la gestión del conocimiento: Un enfoque técnico práctico. RIDE Rev. Iberoam. Investig. Desarro. Educ. 2018, 8, 130–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nitzl, C.; Chin, W.W. The case of partial least squares (PLS) path modeling in managerial accounting research. J. Manag. Control 2017, 28, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. MIS Q. 1998, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Cheah, J.H. Partial least squares structural equation modeling using SmartPLS: A software review. J. Mark. Anal. 2019, 7, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, O.; Olague, J. Modelo de ecuaciones estructurales por el método de mínimos cuadrados parciales (Partial Least Squares-PLS). In Métodos y Técnicas Cualitativas y Cuantitativas Aplicables a la Investigación en Ciencias Sociales; Sáenz, K., Tamez, G., Eds.; Tirant Humanidades México: Monterrey, Mexico, 2014; pp. 480–497. ISBN 9788416062324. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; ISBN 9780962262845. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 9780203771587. [Google Scholar]

- Rositas Martínez, J. Factores Críticos de Éxito en la Gestión de Calidad y su Grado de Presencia e Impacto en la Industria Manufacturera Mexicana. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, San Nicolás de los Garza, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Arias, M. ¿Qué significa realmente el valor de p? Rev. Pediatr. Aten. Primaria 2017, 19, 377–381. [Google Scholar]

- Manterola, D.C.; Pineda, N.V. El valor de “p” y la “significación estadística”. Aspectos generales y su valor en la práctica clínica. Rev. Chil. Cir. 2008, 60, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rositas Martínez, J. Los tamaños de las muestras en encuestas de las ciencias sociales y su repercusión en la generación del conocimiento. Innov. Neg. 2014, 11, 235–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, E.; Ayavoo, R. The mediating role of knowledge application in the relationship between knowledge management practices and firm innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2020, 5, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy & Society the Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

| Evaluation of the Reflective Measurement Model |

|---|

|

| Evaluation Structural Model |

|

| Convergent Validity | Internal Consistency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct (Indicators) | Load Factor (λ) | Reliability of the Indicator | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | Composite Reliability (FC) | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) |

| Knowledge management | 0.570 | 0.869 | 0.811 | ||

| Employees come up with new ideas and knowledge | 0.738 | 0.754 | |||

| The company learns from the environment by being attentive to change | 0.716 | 0.716 | |||

| Activities are carried out in the company to convert knowledge into action plans | 0.777 | 0.761 | |||

| Everyone is informed of the company’s performance | 0.743 | 0.753 | |||

| New ideas from employees are presented to others in the company | 0.781 | 0.789 | |||

| Sustainability | 0.901 | 0.922 | 0.628 | ||

| Employees are well remunerated | 0.760 | 0.789 | |||

| There is concern for the health of its employees | 0.694 | 0.704 | |||

| Employees are provided with benefits in addition to those provided by law | 0.776 | 0.749 | |||

| Employees are provided with training and development | 0.776 | 0.762 | |||

| Innovation | 0.743 | 0.838 | 0.565 | ||

| Employee initiatives to create new ideas are recognized | 0.744 | 0.754 | |||

| Employee creativity is encouraged | 0.786 | 0.791 | |||

| New ways of achieving success are constantly being created | 0.808 | 0.805 | |||

| Improving products, work processes, and ideas that have been implemented over time | 0.805 | 0.783 | |||

| Correct mistakes and turn them into opportunities to improve processes, services, or products | 0.832 | 0.828 | |||

| New ways of working are generated in order to compete | 0.804 | 0.805 | |||

| Innovate to achieve company growth | 0.776 | 0.779 | |||

| Knowledge Management | Innovation | Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge management | 0.755 | ||

| Innovation | 0.538 | 0.792 | |

| Sustainability | 0.704 | 0.504 | 0.751 |

| Knowledge Management | Innovation | Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator 1 | 0.754 | 0.445 | 0.540 |

| Indicator 2 | 0.716 | 0.344 | 0.506 |

| Indicator 3 | 0.761 | 0.420 | 0.473 |

| Indicator 4 | 0.753 | 0.402 | 0.557 |

| Indicator 5 | 0.789 | 0.415 | 0.575 |

| Indicator 6 | 0.612 | 0.436 | 0.789 |

| Indicator 7 | 0.460 | 0.433 | 0.704 |

| Indicator 8 | 0.478 | 0.314 | 0.749 |

| Indicator 9 | 0.548 | 0.325 | 0.762 |

| Indicator 10 | 0.452 | 0.754 | 0.395 |

| Indicator 11 | 0.430 | 0.791 | 0.414 |

| Indicator 12 | 0.430 | 0.805 | 0.409 |

| Indicator 13 | 0.373 | 0.783 | 0.343 |

| Indicator 14 | 0.415 | 0.828 | 0.390 |

| Indicator 15 | 0.433 | 0.805 | 0.409 |

| Indicator 16 | 0.440 | 0.779 | 0.421 |

| Knowledge Management | Innovation | Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge management | |||

| Innovation | 0.626 | ||

| Sustainability | 0.896 | 0.610 |

| Construct | Knowledge Management | Innovation | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge management | 1.000 | 1.407 | |

| Innovation | 1.407 | ||

| Sustainability |

| Construct | R² |

R² Adjusted | Q² | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge management | 0.069 | |||

| Innovation | 0.289 | 0.288 | 0.168 | |

| Sustainability | 0.518 | 0.516 | 0.272 |

| Construct | Knowledge Management | Innovation | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge management | 0.407 | 0.548 | |

| Innovation | 0.046 | ||

| Sustainability |

| Hypothesis |

Path Coefficients β | T Score | p Value | Accepted/Rejected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1. KM → SUS | 0.609 | 14.918 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2. KM → INN | 0.538 | 12.339 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3. INN → SUS | 0.176 | 3.695 | 0.000 | Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ochoa-Jiménez, S.; Leyva-Osuna, B.A.; Jacobo-Hernández, C.A.; García-García, A.R. Knowledge Management in Relation to Innovation and Its Effect on the Sustainability of Mexican Tourism Companies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413790

Ochoa-Jiménez S, Leyva-Osuna BA, Jacobo-Hernández CA, García-García AR. Knowledge Management in Relation to Innovation and Its Effect on the Sustainability of Mexican Tourism Companies. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413790

Chicago/Turabian StyleOchoa-Jiménez, Sergio, Beatriz Alicia Leyva-Osuna, Carlos Armando Jacobo-Hernández, and Alma Rocío García-García. 2021. "Knowledge Management in Relation to Innovation and Its Effect on the Sustainability of Mexican Tourism Companies" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413790

APA StyleOchoa-Jiménez, S., Leyva-Osuna, B. A., Jacobo-Hernández, C. A., & García-García, A. R. (2021). Knowledge Management in Relation to Innovation and Its Effect on the Sustainability of Mexican Tourism Companies. Sustainability, 13(24), 13790. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413790