Changes in Drop Out Intentions: Implications of the Motivational Climate, Goal Orientations and Aspects of Self-Worth across a Youth Sport Season

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

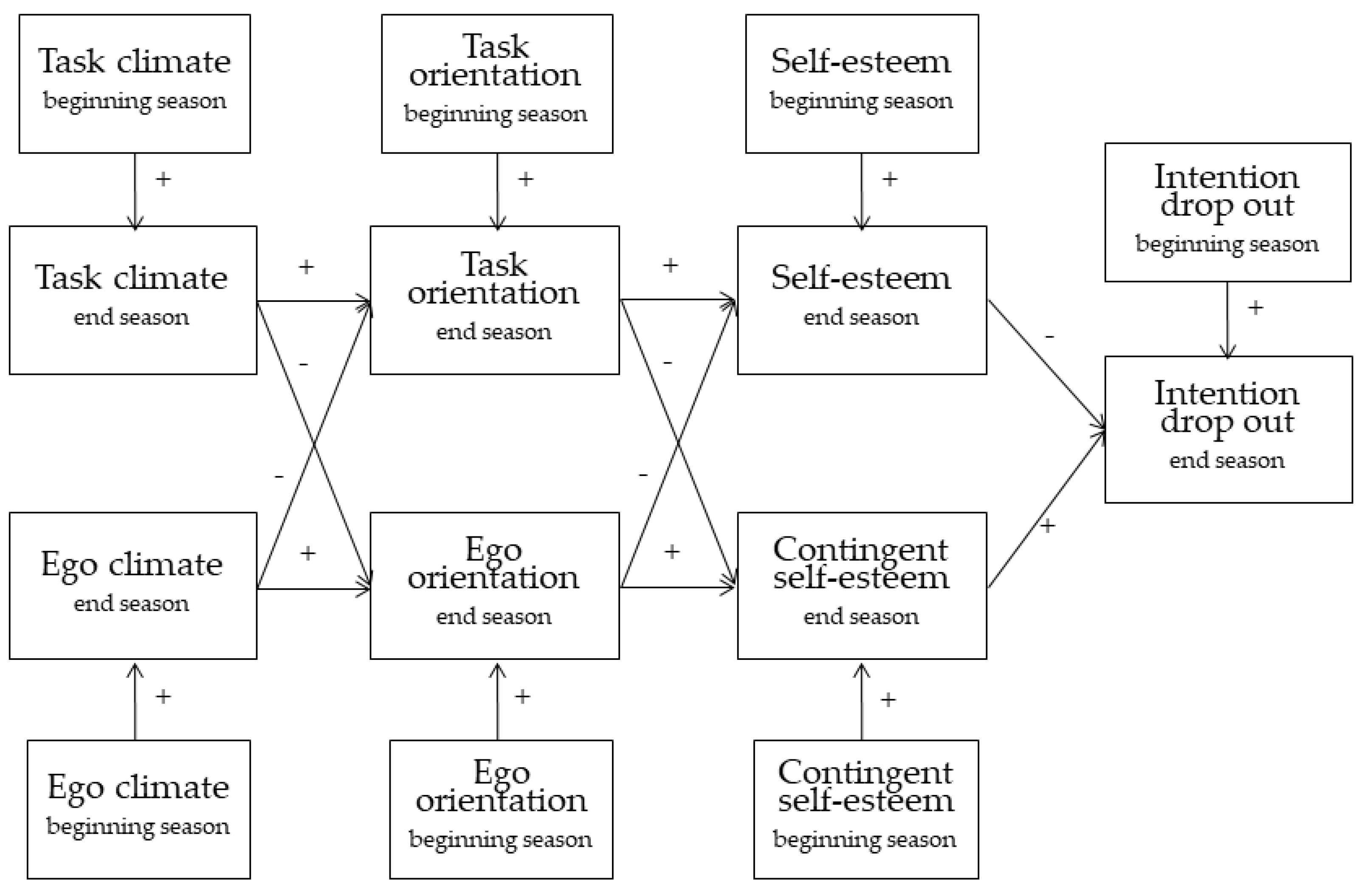

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersen, T.R.; Schmidt, J.F.; Nielsen, J.J.; Randers, M.B.; Sundstrup, E.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Andersen, L.L.; Suetta, C.; Aagaard, P.; Bangsbo, J.; et al. Effect of football or strength training on functional ability and physical performance in untrained old men. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, T.R.; Schmidt, J.F.; Thomassen, M.; Hornstrup, T.; Frandsen, U.; Randers, M.B.; Hansen, P.R.; Krustrup, P.; Bangsbo, J. A preliminary study: Effects of football training on glucose control, body composition, and performance in men with type 2 diabetes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24 (Suppl. S1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, S.; Urrea, A. Influencia del deporte y la actividad física en el estado de salud físico y mental: Una revisión bibliográfica. Rev. Katharsis 2018, 25, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, M.V.; Fukui, R.; Krustrup, P.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Silva, P.R.S.; Rodrigues, A.C.; De Andrade, J.L.; Hernandez, A.J.; Silva, M.E.R. Positive effects of football on fitness, lipid profile, and insulin resistance in Brazilian patients with type 2 diabetes. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24 (Suppl. S1), 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faude, O.; Kerper, O.; Multhaupt, M.; Winter, C.; Beziel, K.; Junge, A.; Meyer, T. Football to tackle overweight in children. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malm, C.; Jakobsson, J.; Isaksson, A. Physical Activity and Sports—Real Health Benefits: A Review with Insight into the Public Health of Sweden. Sports 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batista, M.B.; Romanzini, C.L.P.; Barbosa, C.C.L.; Shigaki, G.B.; Romanzini, M.; Ronque, E.R.V. Participation in sports in childhood and adolescence and physical activity in adulthood: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2019, 37, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, M.; Sabiston, C.M.; Barnett, T.A.; O’Loughlin, E.; Ward, S.; Contreras, G.; O’Loughlin, J. Number of years of participation in some, but not all, types of physical activity during adolescence predicts level of physical activity in adulthood: Results from a 13-year study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kjønniksen, L.; Torsheim, T.; Wold, B. Tracking of leisure-time physical activity during adolescence and young adulthood: A 10-year longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Telama, R.; Yang, X.; Hirvensalo, M.; Raitakari, O. Participation in Organized Youth Sport as a Predictor of Adult Physical Activity: A 21-Year Longitudinal Study. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2006, 18, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiché, J.C.; Sarrazin, P. Proximal and distal factors associated with dropout versus maintained participation in organized sport. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2009, 8, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cervello, E.; Escartí, A.; Guzmán, J.F. Youth sport dropout from the achievement goal theory. Psicothema 2007, 19, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fraser-Thomas, J.; Côté, J.; Deakin, J. Understanding dropout and prolonged engagement in adolescent competitive sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2008, 9, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bélanger, M.; Gray-Donald, K.; O’Loughlin, J.; Paradis, G.; Hanley, J. When Adolescents Drop the Ball: Sustainability of Physical Activity in Youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, M.W.; Chad, K.E.; Beattie-Flath, J.A.; Humbert, M.L.; Verrall, T.C.; Vu, L.; Muhajarine, N. Examination of physical activity in adolescents over the school year. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2009, 21, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman, B.; Serra-Majem, L.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Perez-Rodrigo, C.; Aranceta, J. How many children and adolescents in Spain comply with the recommendations on physical activity? J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 2008, 48, 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Chillón, P.; Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.; Pérez, I.J.; Martín-Matillas, M.; Valtueña, J.; Gómez_Martínez, S.; Redondo, C.; Rey-López, J.P.; Castillo, M.J.; et al. Socio-economic factors and active commuting to school in urban Spanish adolescents: The AVENA study. Eur. J. Public Health 2009, 19, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Currie, C.; Gabbain, S.N.; Godeau, E.; Roberts, C.; Smith, R.; Currie, D.; Pickett, W.; Richter, M.; Morgan, A.; Barnekow, V. Inequalities in Young People’s Health: HBSC International Report from the 2005/2006 Survey; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dumith, S.C.; Gigante, D.P.; Domingues, M.R.; Kohl, H.W. Physical activity change during adolescence: A systematic review and a pooled analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eime, R.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.; Payne, W. Population levels of sport participation: Implications for sport policy. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García-Calvo, T.; Cervelló, E.; Jiménez, R.; Iglesias, D.; Moreno-Murcia, D. Using self-determination theory to explain sport persistence and dropout in adolescent athletes. Span. J. Psychol. 2010, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knuth, A.G.; Hallal, P.C. Temporal Trends in Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. J. Phys. Act. Health 2009, 6, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, B.S.; Hosking, J.; Jeffery, A.N.; Henley, W.E.; Wilkin, T.J. Exploring the Adolescent Fall in Physical Activity: A 10-yr cohort study (EarlyBird 41). Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Møllerløkken, N.E.; Lorås, H.; Pedersen, A. V A systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in youth soccer. Percept. Mot. Skills 2015, 121, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, C. Classrooms: Goals, structures, and motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.G. The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, J.G. Conceptions of ability and achievement motivation. In Research on Motivation in Education: Students Motivation; Ames, R., Ames, C., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, C. Achievement goals and the classroom motivational climate. In Student Perceptions in the Classroom; Schunk, D., Meece, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Motivational processes affecting learning. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.-R.; Lam, M.H.S.; Ku, S.; Li, H.C.W.; Lee, K.Y.; Ho, E.; Flint, S.W.; Wong, A.S.W. The reasons of dropout of sport in Hong Kong school athletes. Health Psychol. Res. 2017, 5, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keathley, K.; Himelein, M.J.; Srigley, G. Youth soccer participation and withdrawal: Gender similarities and differences. J. Sport Behav. 2013, 36, 171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Macarro, J.; Romero, C.; Torres, J. Reasons why higher secondary school students in the province of Granada dropout of sports and organized physical activities. Rev. Educ. 2010, 353, 495–519. [Google Scholar]

- Molinero, O.; Salguero, A.; Tuero, C.; Álvarez, E.; Márquez, S. Dropout reasons in young Spanish athletes: Relationship to gender, type of sport and level of competition. J. Sport Behav. 2006, 29, 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Molinero, O.; Salguero, A.; Álvarez, E.; Márquez, S. Reasons for dropout in youth soccer: A comparison with other team sports. Eur. J. Hum. Mov. 2009, 22, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, D.; Cid, L.; Marinho, D.A.; Moutão, J.; Vitorino, A.; Bento, T. Determinants and Reasons for Dropout in Swimming —Systematic Review. Sports 2017, 5, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rottensteiner, C.; Laakso, L.; Pihlaja, T.; Konttinen, N. Personal Reasons for Withdrawal from Team Sports and the Influence of Significant others among Youth Athletes. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2013, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, T.; Löbig, A.; Ehnold, P.; Nagel, S. What is influencing the dropout behaviour of youth players from organised football? Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2018, 48, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.; Duda, J.L.; Yin, Z. Examination of the psychometric properties of the Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire—2 in a sample of female athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2000, 18, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, S.; Haug, E.M.; Ommundsen, Y. A Conditional Process Analysis of the Coach-Created Mastery Climate, Task Goal Orientation, and Competence Satisfaction in Youth Soccer: The Moderating Role of Controlling Coach Behavior. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2018, 31, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Gallegos, A.; Gómez-López, M.; Rodríguez-Suárez, N.; Abraldes, J.A.; Alesi, M.; Bianco, A. Importance of the Motivational Climate in Goal, Enjoyment, and the Causes of Success in Handball Players. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harwood, C.G.; Keegan, R.; Smith, J.M.; Raine, A.S. A systematic review of the intrapersonal correlates of motivational climate perceptions in sport and physical activity. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 18, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingrell, J.; Johnson, U.; Ivarsson, A. Achievement goals in youth sport and the influence of coaches, peers, and parents: A longitudinal study. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 570–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M.; Zazo, R.; Çetinkalp, Z.K.; Wright, T.; Graham, K.-A.; Konttinen, N. A meta-analytic review of achievement goal orientation correlates in competitive sport: A follow-up to Lochbaum et al. (2016). Kinesiology 2016, 48, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newton, M.L. The Effects of Differences in Perceived Motivational Climate and Goal Orientations on Motivational Responses of Female Volleyball Players; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, M.Z.; San José, S.P.; González, M.V. Motivational analysis during one season in female football in Castilla y León (Spain) (Análisis motivacional durante una temporada de fútbol femenino en Castilla y León (España)). Retos 2020, 40, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.R.; Johnson, D.M.; Force, E.C.; Petrie, T.A. Peers, parents, and coaches, oh my! The relation of the motivational climate to boys’ intention to continue in sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Parker, J.; Barnes, J. Multi-dimensional adolescent self-concepts: Their relationship to age, sex and academic measures. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1985, 22, 422–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Human autonomy: The basis for true self-esteem. In Efficacy, Agency, and Self-Esteem; Kemis, M., Ed.; Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, J.; Pérez-García, A.M.; Ruiz, J.A.; Sanjuán, P.; Rueda, B. Psicologia de La Personalidad; UNED: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kavussanu, M.; Harnisch, D.L. Self-esteem in children: Do goal orientations matter? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 70, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bars, H.; Gernigon, C.; Ninot, G. Personal and contextual determinants of elite young athletes’ persistence or dropping out over time. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2009, 19, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinboth, M.; Duda, J.L. Motivational climate, perceived ability, and athletes’ psychological and physical well-being. Sport Psychol. 2004, 18, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Campbell, J.D.; Krueger, J.I.; Vohs, K.D. Does High Self-Esteem Cause Better Performance, Interpersonal Success, Happiness, or Healthier Lifestyles? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2003, 4, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balaguer, I.; Castillo, I.; Duda, J.L. Interrelaciones entre el clima motivacional y la cohesión en futbolistas cadetes. eduPsykhé 2003, 2, 243–258. [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer, I.; Castillo, I.; Tomás, I. Análisis de las propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario de Orientación al Ego y a la Tarea en el Deporte (TEOSQ) en su traducción al castellano. Psicológica 1996, 17, 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, J.L. The relationship between task and ego orientation and the perceived purpose of sport among male and female high school athletes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1989, 11, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duda, J.L.; Nicholls, J.G. Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and Sport. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, I.; Castillo, I.; Duda, J.L. Apoyo a la autonomía, satisfacción de las necesidades, motivación y bienestar en deportistas de competición: Un análisis de la teoría de la autodeterminación. Rev. Psicol. Deport. 2008, 17, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Richards, G.E.; Johnson, S.; Roche, L.; Tremayne, P. Physical Self-Description Questionnaire: Psychometric properties and a multitrait multimethod analysis of relations to existing instruments. J. Sport. Exerc. Psychol. 1994, 16, 270–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietjens, M.; Freund, P.A.; Büsch, D.; Strauss, B. Using mixture distribution models to test the construct validity of the Physical Self-Description Questionnaire. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2012, 13, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, E.; Ntoumanis, N.; Viladrich, C.; Haug, E.; Ommundsen, Y.; Van Hoye, A.; Mercé, J.; Hall, H.K.; Zourbanos, N.; Duda, J.L. Intentions to drop-out of youth soccer: A test of the basic needs theory among European youth from five countries. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 11, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.L.; Quested, E.; Haug, E.; Samdal, O.; Wold, B.; Balaguer, I.; Castillo, I.; Sarrazin, P.; Papaioannou, A.; Ronglan, L.T.; et al. Promoting Adolescent health through an intervention aimed at improving the quality of their participation in Physical Activity (PAPA): Background to the project and main trial protocol. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 11, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8.80 [computer software]; Scientific Software International, Inc.: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P. Evaluating model fit. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, D.A.; Maxwell, S.E. Multitrait-Multimethod Comparisons Across Populations: A Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1985, 20, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin, P.; Vallerand, R.; Guillet, E.; Pelletier, L.; Cury, F. Motivation and dropout in female handballers: A 21-month prospective study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vazou, S. Variations in the perceptions of peer and coach motivational climate. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2010, 81, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinn, B.; Vincent, V.; Semper, T.; Jorgensen, L. Activity Involvement, Goal Perspective, and Self-Esteem among Mexican American Adolescents. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treasure, D.C.; Biddle, S. Antecedents of physical self-worth and global self-esteem: Influence of achievement goal orientations and perceived ability. In Proceedings of the The Annual Conference of the North American Society of the Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity, Denver, CO, USA, 11–13 June 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gjesdal, S.; Appleton, P.R.; Ommundsen, Y. Both the “What” and “Why” of Youth Sports Participation Matter: A Conditional Process Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

| Time 1 | Time 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Mean | SD | Alpha | Mean | SD | t | |

| Task-involving climate | 0.80 | 4.28 | 0.60 | 0.85 | 4.16 | 0.69 | 4.47 ** |

| Ego-involving climate | 0.75 | 2.37 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 2.46 | 0.92 | −2.22 * |

| Task orientation | 0.84 | 4.45 | 0.61 | 0.86 | 4.35 | 0.68 | 3.22 ** |

| Ego orientation | 0.83 | 2.89 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 2.87 | 1.10 | 0.57 |

| Self-esteem | 0.86 | 4.26 | 0.68 | 0.87 | 4.18 | 0.76 | 2.50 * |

| Contingent self-worth | 0.82 | 2.86 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 2.72 | 0.90 | 2.48 * |

| Intention to drop out | 0.71 | 1.51 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 1.74 | 0.80 | −6.54 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fabra, P.; Castillo, I.; González-García, L.; Duda, J.L.; Balaguer, I. Changes in Drop Out Intentions: Implications of the Motivational Climate, Goal Orientations and Aspects of Self-Worth across a Youth Sport Season. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413850

Fabra P, Castillo I, González-García L, Duda JL, Balaguer I. Changes in Drop Out Intentions: Implications of the Motivational Climate, Goal Orientations and Aspects of Self-Worth across a Youth Sport Season. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413850

Chicago/Turabian StyleFabra, Priscila, Isabel Castillo, Lorena González-García, Joan L. Duda, and Isabel Balaguer. 2021. "Changes in Drop Out Intentions: Implications of the Motivational Climate, Goal Orientations and Aspects of Self-Worth across a Youth Sport Season" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413850

APA StyleFabra, P., Castillo, I., González-García, L., Duda, J. L., & Balaguer, I. (2021). Changes in Drop Out Intentions: Implications of the Motivational Climate, Goal Orientations and Aspects of Self-Worth across a Youth Sport Season. Sustainability, 13(24), 13850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413850