Influence of Government Support on Proactive Environmental Strategies in Family Firms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

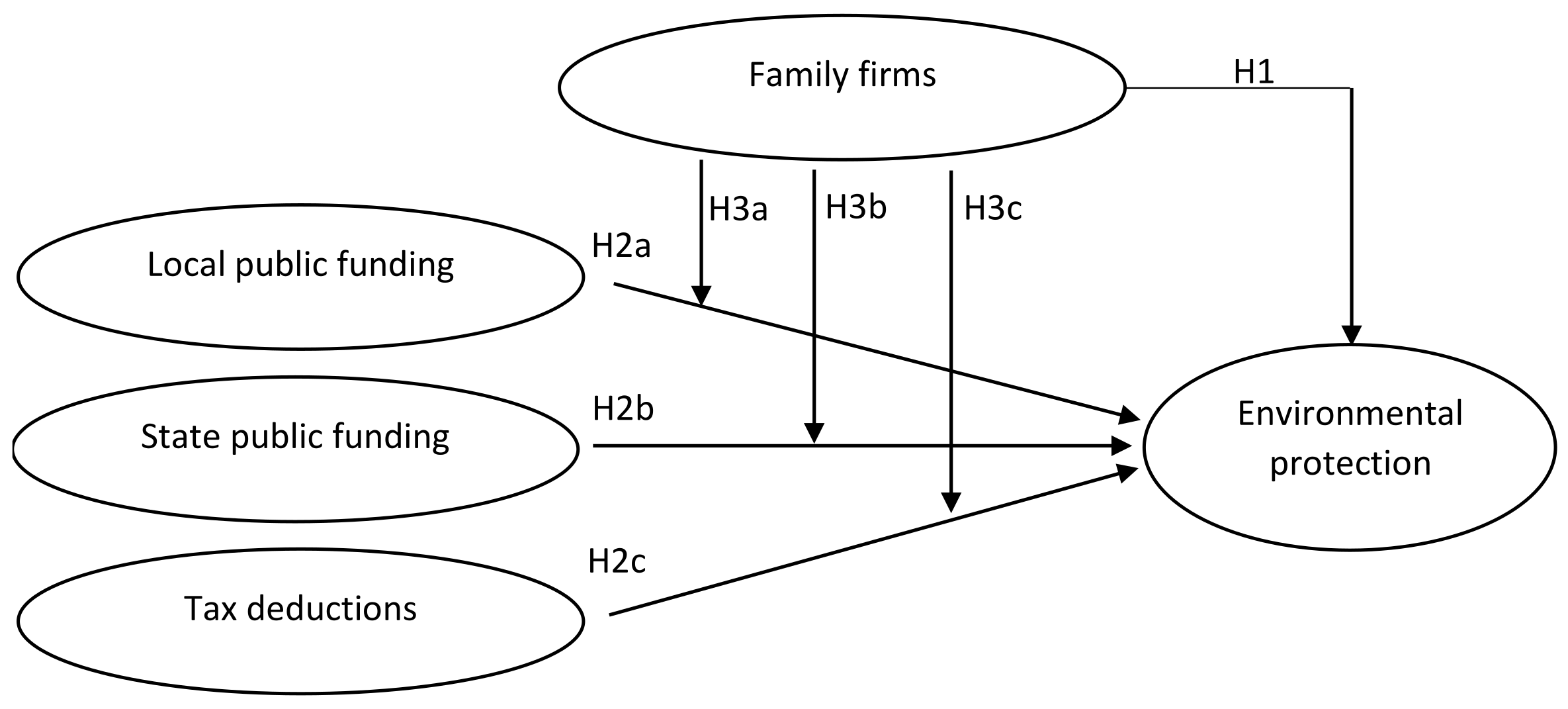

2.1. Family Nature and PES

2.2. Government Support towards PES

2.2.1. Direct and Indirect Public Support

2.2.2. Direct and Indirect Government Support and Family Firms

3. Data Analysis and Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis Methodology

3.4. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Comission. A Renewed EU Strategy 2011–2014 for CSR. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_11_730 (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Hecker, R. Capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from an Australian manufacturing industry sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cosma, S.; Schwizer, P.M.; Nobile, L.; Leopizzi, R. Environmental attitude on the board. Who are the “green directors”? Evidences from Italy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 3360–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Vredenburg, H. Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable organizational capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Sharma, S. A contingent resource-based view of proactive corporate environmental strategy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. Adopting proactive environmental strategy: The influence of stakeholders and firm size. J. Manag. Stud. 2010, 47, 1072–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Drivers of proactive environmental strategy in family firms. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H.; Sharma, P. Trends and directions in the development of a strategic management theory of the family firm. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.; Nuñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.A.; Haynes, G.W.; Schrank, H.L.; Danes, S.M. Socially responsible processes of small family business owners: Exploratory evidence from the national family business survey. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 524–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cózar-Navarro, C.; Priede-Bergamini, T.; Benito-Hernandez, S. The Link between Firm Size and Corporate Social Responsibility. Ethical Perspect. 2017, 24, 259–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Wagner, M. The effect of family ownership on different dimensions of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from large US firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Presas, P.; Simon, A. The heterogeneity of family firms in CSR engagement: The role of values. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hilliard, I.; Priede, T. Benchmarking responsible management and non-financial reporting. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 2931–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Dibrell, C. The natural environment, innovation, and firm performance: A comparative study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2006, 19, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.; Hasso, T. Environmental Performance Focus in Private Family Firms: The Role of Social Embeddedness. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doluca, H.; Wagner, M.; Block, J. Sustainability and environmental behaviour in family firms: A longitudinal analysis of environment-related activities, innovation and performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 152–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Nastasi, A.; Pisa, S. A comparison of family and nonfamily small firms in their approach to green innovation: A study of Italian companies in the agri-food industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Su, E.; Wang, S. When Does Family Ownership Promote Proactive Environmental Strategy? The Role of the Firm’s Long-Term Orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Bruthland Report. New York. Available online: http://www.ecominga.uqam.ca/PDF/BIBLIOGRAPHIE/GUIDE_LECTURE_1/CMMAD-Informe-Comision-Brundtland-sobre-Medio-Ambiente-Desarrollo.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2021).

- Van Gils, A.; Dibrell, C.; Neubaum, D.O.; Craig, J.B. Social issues in the family enterprise. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samara, G.; Jamali, D.; Sierra, V.; Parada, M.J. Who are the best performers? The environmental social performance of family firms. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2018, 9, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Swaen, V.; Lindgreen, A.; Sen, S. The roles of leadership styles in corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tagiuri, R.; Davis, J.A. On the goals of successful family companies. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1992, 5, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, N.C.; Hatten, K.J. Non-market-based transfers of wealth and power: A research framework for family businesses. Am. J. Small Bus. 1987, 11, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Eddleston, K.A.; Kellermanns, F.W. Exploring the concept of familiness: Introducing family firm identity. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2010, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzelli, A.; Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A. Blending in while standing out: Selective conformity and new product introduction in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pérez, M.E.; Melero-Polo, I.; Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; Cambra-Fierro, J. Sustainability and business outcomes in the context of SMEs: Comparing family firms vs. non-family firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuttner, M.; Feldbauer-Durstmüller, B.; Mitter, C. Corporate social responsibility in Austrian family firms: Socioemotional wealth and stewardship insights from a qualitative approach. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2021, 11, 238–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, A.; Principale, S.; Ligorio, L.; Cosma, S. Walking the talk in family firms. An empirical investigation of CSR communication and practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curado, C.; Mota, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Sustainability in Family Firms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Larraza–Kintana, M.; Garcés–Galdeano, L.; Berrone, P. Are family firms really more socially responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campopiano, G.; De Massis, A. Corporate social responsibility reporting: A content analysis in family and non-family firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 511–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton-Miller, I.; Miller, D. Family firms and practices of sustainability: A contingency view. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2016, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Yang, M.L.; Wong, Y.J. The effect of internal factors and family influence on firms’ adoption of green product innovation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1167–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memili, E.; Fang, H.C.; Koc, B.; Yildirim-Oktem, O.; Sonmez, S. Sustainability practices of family firms: The interplay between family ownership and long-term orientation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R. The many and the few: Rounding up the SMEs that manage CSR in the supply chain. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 14, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisetti, C.; Mancinelli, S.; Mazzanti, M.; Zoli, M. Financial barriers and environmental innovations: Evidence from EU manufacturing firms. Clim. Policy 2017, 17, S131–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero, Á.; Cuerva, M.C.; Álvarez-Aledo, C. Environmental innovation and employment: Drivers and synergies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ociepa-Kubicka, A.; Pachura, P. Eco-innovations in the functioning of companies. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpellini, S.; Marín-Vinuesa, L.M.; Portillo-Tarragona, P.; Moneva, J.M. Defining and measuring different dimensions of financial resources for business eco-innovation and the influence of the firms’ capabilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horbach, J. Determinants of environmental innovation—New evidence from German panel data sources. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Marchi, V. Environmental innovation and R&D cooperation: Empirical evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Guerra, D.; van der Zwan, P. What drives environmental practices of SMEs? Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecere, G.; Corrocher, N.; Mancusi, M.L. Financial constraints and public funding of eco-innovation: Empirical evidence from European SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 54, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanes, J.V.; Busom, I. Who participates in R&D subsidy programs? The case of Spanish Manufacturing firms. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 1459–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, M.; Zoboli, R. The drivers of environmental innovation in local manufacturing systems. Econ. Política 2005, 22, 399–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, J.B.; Dyer, W.G.; Smith, I.; Adams, G.L. A stakeholder identity orientation approach to corporate social performance in family firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, E.; Martínez-Ferrero, J.; García-Meca, E. Corporate social responsibility in family firms: A contingency approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 1044–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; Gómez-López, R. Determinants of innovation decision in small and medium-sized family enterprises. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2016, 23, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, D.; Stephan, A.; Mosquera, J.S. Family ownership: Does it matter for funding and success of corporate innovations? Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, L. Lean innovation: Family firm succession and patenting strategy in a dynamic institutional landscape. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2019, 10, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzaneque, M.; Rojo-Ramírez, A.A.; Diéguez-Soto, J.; Martínez-Romero, M.J. How negative aspiration performance gaps affect innovation efficiency. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 54, 209–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavati, S. Corporate social performance in family firms: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2018, 8, 235–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alonso, R.; Martínez-Romero, M.J.; Rojo-Ramírez, A.A. Examining the Impact of Innovation Forms on Sustainable Economic Performance: The Influence of Family Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fariñas, J.C.; Jaumandreu, J. Diez años de encuesta sobre estrategias empresariales (ESEE). Econ. Ind. 1999, 329, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaco, S.; Crifo, P. CSR and financial performance: Complementarity between environmental, social and business behaviors. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 3323–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnhart, D. The effect of corporate environmental performance on corporate financial performance. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Araque, B.; Hernández, J.P.S.-I.; Gutiérrez-Broncano, S.; Jiménez-Estévez, P. Corporate social responsibility in micro-, small-and medium-sized enterprises: Multigroup analysis of family vs. nonfamily firms. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubaum, D.O.; Dibrell, C.; Craig, J.B. Balancing natural environmental concerns of internal and external stakeholders in family and non-family businesses. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2012, 3, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bai, Y. An Analysis on the Influence of R&D Fiscal and Tax Subsidies on Regional Innovation Efficiency: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 12707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | |

|---|---|

| Unit Questionnaire design Population types Time period | Spanish manufacturing sector SEPI Foundation More than 100,000 elements. Data from 2016 |

| Sampling | |

| Type of sampling Sample size Sampling error (approx.) Level of confidence Data treatment | Random stratified census according to activity sector and firm size. 1802 Spanish manufacturing firms 0.028 (p = q = 0.50) 95% (K = 2 sigma) Statistical Solutions for Products and Services (SPSS). |

| Type of Variable | Study Variables | Variable to Analyze | Definition | Name | Values and Data Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Environmental protection | Expenses on environmental protection | Categorical variable that indicates whether the company spends to control of environmental pollution. | EP | 1 = Expenditures on environmental protection. 0 = No expenditures on environmental protection. |

| Independent | Family nature | Family business | Indicates whether the company has family character or not. | FB | 1 = Family Business 0 = Non-family business. |

| Government support | Local direct financing | Financial resources received from the local administration. | LF | Total local financing. | |

| State direct financing | Financial resources received from the central/state administration | SF | Total state financing. | ||

| Other public financing | Other public financing | OPF | Total other public financing | ||

| Indirect support. Tax deductions | Total value of the deductions applied in corporate tax. | TD | Total tax deductions. | ||

| Control | Size | SIZ | Number of employees | ||

| Income | INC | Total incomes | |||

| Age | AGE | Number of years since incorporation | |||

| Spanish Companies (n = 1802) | Mean | Standard Deviation | EP | FB | LF | SF | OTF | TD | SIZ | INC | AGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | 0.55 | 0.497 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| FB | 0.44 | 0.496 | 0.049 * | 1.00 | |||||||

| LF | 11.53 | 193.723 | 0.124 ** | 0.002 | 1.00 | ||||||

| SF | 31.51 | 410.282 | 0.150 ** | 0.035 | 0.011 | 1.00 | |||||

| OTF | 15.92 | 289.491 | 0.119 ** | 0.021 | 0.105 ** | 0.175 ** | 1.00 | ||||

| TD | 49,646.64 | 410,896.107 | 0.242 ** | 0.050 * | 0.180 ** | 0.096 ** | 0.011 | 1.00 | |||

| SIZ | 153.16 | 592.542 | 0.391 ** | 0.034 | 0.294 ** | 0.131 ** | 0.528 ** | 0.534 ** | 1.00 | ||

| INC | 53,140,267.08 | 315,201,465.318 | 0.420 ** | 0.017 | 0.359 ** | 0.057 * | 0.138 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.698 ** | 1.00 | |

| AGE | 36.65 | 18.896 | 0.101 ** | 0.105 ** | 0.010 | 0.074 ** | 0.068 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.129 ** | 0.067 ** | 1.00 |

| Sample (n = 1594) | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| FB | 56.4 | 43.6 |

| EP | 44.6 | 55.4 |

| Model | Without Interaction | With Interactions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Hypotheses | Values | Values |

| FB | H1 | 0.226 ** | 0.134 |

| LF | H2a | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| SF | H2b | 0.002 * | 0.001 |

| OTF | H2b | 0.017 ** | 0.006 |

| TD | H2c | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| SIZE | - | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** |

| INC | - | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** |

| AGE | - | 0.001 | 0.005 |

| FAM*LF | H3a | 0.003 | |

| FAM*SF | H3b | 0.022 ** | |

| FAM*OTF | H3b | 0.029 | |

| FAM*TD | H3c | 0.001 * | |

| Const. | - | −0.646 | 0.607 |

| R2 (Nagelkerke) | 0.197 | 0.208 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benito-Hernández, S.; López-Cózar-Navarro, C.; Priede-Bergamini, T. Influence of Government Support on Proactive Environmental Strategies in Family Firms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13973. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413973

Benito-Hernández S, López-Cózar-Navarro C, Priede-Bergamini T. Influence of Government Support on Proactive Environmental Strategies in Family Firms. Sustainability. 2021; 13(24):13973. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413973

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenito-Hernández, Sonia, Cristina López-Cózar-Navarro, and Tiziana Priede-Bergamini. 2021. "Influence of Government Support on Proactive Environmental Strategies in Family Firms" Sustainability 13, no. 24: 13973. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413973

APA StyleBenito-Hernández, S., López-Cózar-Navarro, C., & Priede-Bergamini, T. (2021). Influence of Government Support on Proactive Environmental Strategies in Family Firms. Sustainability, 13(24), 13973. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413973