Materiality Matrix Use in Aligning and Determining a Firm’s Sustainable Business Model Archetype and Triple Bottom Line Impact on Stakeholders

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Business Models and Stakeholders

2.2. The Materiality Matrix

2.3. Material Issues in the Wine Industry

2.4. Research Proposition

Research proposition: The material issues identified in a company’s materiality matrix (MM) are useful to align and determine the Sustainable Business Model archetype (SBM archetype) and the triple bottom line impact on stakeholders (TLBMC).

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. VCT Sustainability Approach

- Product: provide products of excellence that create the best experience for our customers.

- Customers: create partnerships with our customers.

- Supply Chain: be a partner for our suppliers.

- People: have highly committed employees.

- Society: create shared value for society.

- Environment: be an example for the industry on environmental practices

4.2. VCT MM Evolution

4.3. VCT SBM Elements

- In the Environment Pillar the evolution of its elements is related to the incorporation of the element of circular economy. The “waste” element was replaced by the “circular economy” element. The Environment Pillar elements that remain in 2019 are: water, energy, biodiversity and climate change.

- In the Supply Chain Pillar, the evolution of its elements is related to: first, the replacement of the elements “Carbon Footprint” by “Sustainability Index” and “Packaging” by “Sustainable packaging”, both changes were made by the company in 2018. Second, the incorporation of a new element called “Packaging carbon footprint”, a change made in 2018 and third, the Responsible Supply Chain element was replaced by the Responsible Sourcing element.

- In the Product Pillar, there are no changes related to its elements during the period, the elements are the following: innovation, quality, sustainable attributes, and responsible drinking.

- In the Customers Pillar. there are no changes related to its elements during the period. In the 2017–2019 period, the elements are the following: efficiency in logistics costs, efficiency in CO2 emissions and integral customers.

- In the People Pillar, the evolution of its elements is related to the replacement of the element “Knowledge Center” by “Training” in 2019. The elements of the People Pillar that remain unchanged in the period 2017–2019 are the following: career development, engagement and ethical management.

- In the Society Pillar, the evolution of its elements is related to the incorporation of a new element, called “Entrepreneurship”. The elements of the Society Pillar that remain unchanged in the period 2017-2019 are the following: productive alliances, extension for grape growers, communities and education (training).

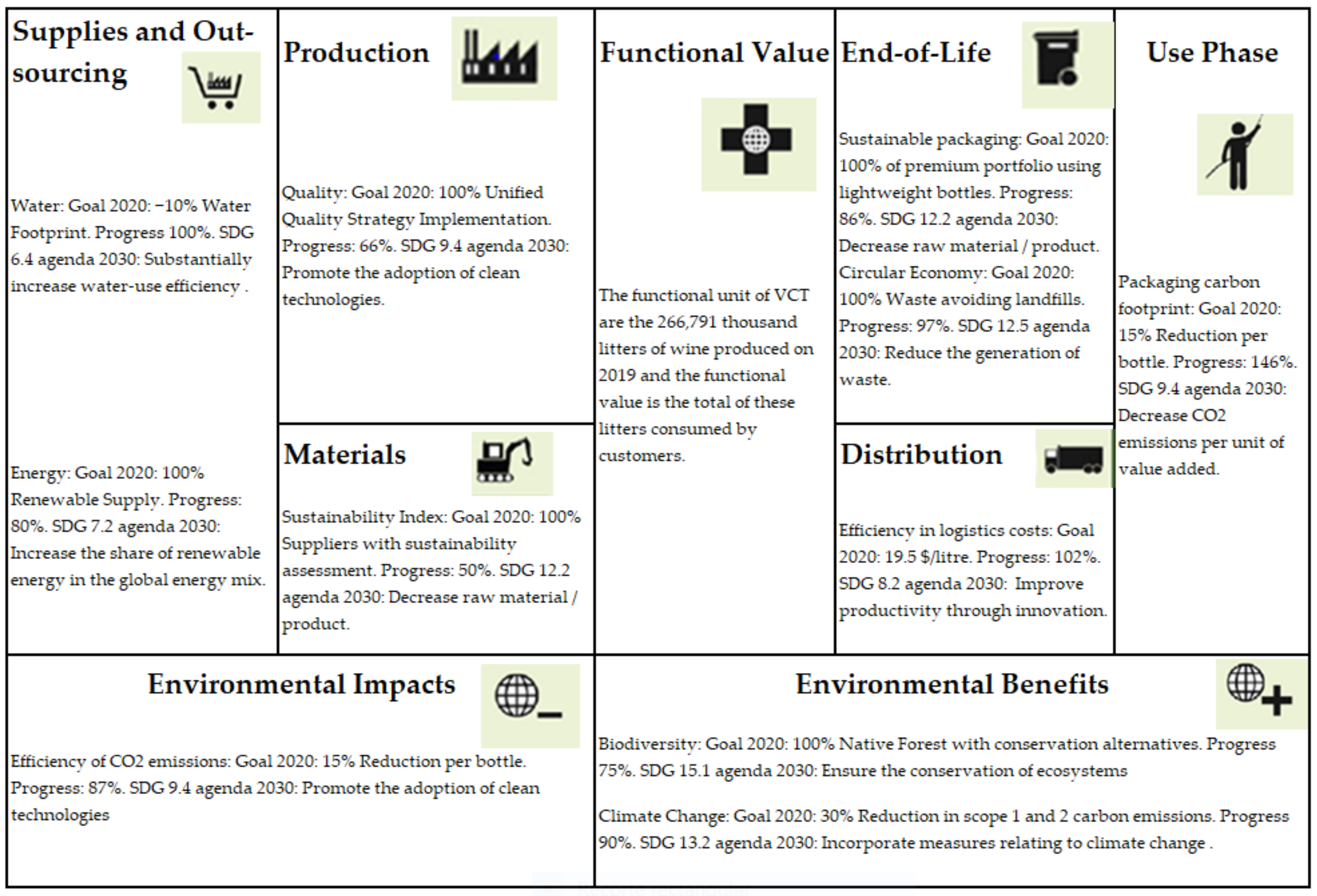

4.4. Developing the Environmental and Social Canvas Layers for VCT

4.5. Aligning the MM with the TLBMC and the SBM Archetypes

- -

- Water management: 10% reduction of water footprint (100%);

- -

- Mitigation and adaptation to climate change: 30% reduction in scope 1 and 2 (90%);

- -

- Employee wellbeing: 100% departments with career plans (50%);

- -

- Waste management and recycling: 100% waste avoiding landfills (97%).

- -

- Technological—maximise material and energy efficiency;

- -

- Technological—substitute with renewables and natural processes;

- -

- Social—adopt a stewardship role;

- -

- Technological—create value from waste.

- SBM archetype 1: maximise material and energy efficiency:

- Value proposition: packaging reduction; introduction of a light bottle with 13% less weight and therefore a reduction in the generation of waste and reduction of emissions in transportation and processing.

- Value creation and delivery: VCT worked with Cristalerías de Chile for the development of the new light bottle, the eco-glass format, which became a standard for the Chilean wine industry.

- Value capture: the light bottle provided for cost savings related to the main input of VCT’s operations.

- SBM archetype 2: create value from ‘waste’:

- Value proposition: currently 98% of waste is recycled, reused or recovered. Organic waste is used to generate compost that is applied again to the earth due to its high organic content, which helps to increase the health and productivity of the soils. VCT is moving towards 100% of waste destined for recycling, reuse or recovery.

- Value creation and delivery: VCT has different alliances for each type of waste to be recovered.

- Value capture: through its circular economy initiatives VCT generates savings for transport and disposal of waste, and the sale of waste. For waste that is generated on a smaller scale, alternatives for use are sought.

- SBM archetype 3: substitute with renewable and natural processes:

- Value proposition: VCT has Initiatives to incorporate renewable energy. The company is moving towards a 100% renewable energy supply in all its facilities.

- Value creation and delivery: in order to communicate this attribute to its consumers, VCT generated a joint project with CRS (Centre for Resource Solutions) to bring to Chile the Green-e renewable energy certification standard, which enables the use of a seal on the product to promote and communicate recognition the said attribute.

- Value capture: the use of renewable energies has meant lower energy costs and a reduced carbon footprint. Through product labelling, VCT communicates this directly to consumers in the most receptive markets—emphasising the sustainable attributes of its products.

- SBM archetype 4: adopt a stewardship role:

- Value proposition: application of ethical standards in the supply chain, through VCT’s established responsible sourcing program.

- Value creation and delivery: through VCT certification of the Sustainability Code of Wines of Chile (Vinos de Chile), environmental and social aspects are worked upon through collaboration with grape suppliers, focusing on agricultural practices.

- Value capture: through supply chain programs, VCT has achieved and enjoys suppliers’ loyalty. There are different types of programs depending on the provider segment. Supply chain programs are in place to enhance and advance suppliers’ quality, productivity, and sustainability. This generates, promotes and fosters suppliers that operate in a coordinated manner with the organisation, improving sustainability and response rates.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Resources Institute. The Elephant in the Boardroom: Why Unchecked Consumption is not an Option in Tomorrow’s Markets. Available online: https://www.wri.org/publication/elephant-in-the-boardroom (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Bocken, N.M.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joyce, A.; Paquin, R.L. The triple layered business model canvas: A tool to design more sustainable business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1474–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, A.; Newton, S.K.; Vega, R.F. Sustainability in the global wine industry: Concepts and cases. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maicas, S.; Mateo, J.J. Sustainability of wine production. Sustainability 2020, 12, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santini, C.; Cavicchi, A.; Casini, L. Sustainability in the wine industry: Key questions and research trends a. Agric. Food Econ. 2013, 1, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freudenreich, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S. A Stakeholder’s theory Perspective on Business Models: Value Creation for Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Forster, W.R. CSR and Stakeholder theory: A Tale of Adam Smith. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, M.; Chamberlain, K.; Graffigna, G. Co-Creating Value in Sustainable and Alternative Food Networks: The Case of Community Supported Agriculture in New Zealand. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder theory and “the corporate objective revisited”. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, I.M.; Jarvis, W.; Soutar, G.; Ouschan, R. Co-creating a CSR Strategy with Customers to Deliver Greater Value. In Disciplining the Undisciplined? CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance, 1st ed.; Brueckner, M., Spencer, R., Paull, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J.J. Co-creation: A Key Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Trust, and Customer Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B. Managing ethically with global stakeholders: A present and future challenge. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2004, 18, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Buchholtz, A. Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability and Stakeholder Management, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J.W. Stakeholder relationships and social welfare: A behavioral theory of contributions to joint value creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, 1st ed.; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. A Friedman doctrine: The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine. 13 September 1970. Available online: https://nyti.ms/1LSi5ZD (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. Stakeholders: Essentially contested or just confused? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lépineux, F. Stakeholder theory, society and social cohesion. Corp. Gov. 2005, 5, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brugann, J.; Prahalad, C.K. Cocreating Businesses’ New Social Compact. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Edward Freeman, R. Stakeholder Management. Available online: https://redwardfreeman.com/stakeholder-management (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Richardson, J. The business model: An integrative framework for strategy. Strateg. Chang. 2008, 17, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Pistoia, A.; Ullrich, S.; Göttel, V. Business models: Origin, development and future research perspectives. Long Range Plann. 2016, 49, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R.; Massa, L. The business model: Recent developments and future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Sustainable business models: Providing a more holistic perspective. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upward, A.; Jones, P. An ontology for strongly sustainable business models: Defining an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science. Organ. Environ. 2016, 29, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add up, 1st ed.; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Taylor and Francis London: Earthscan, UK, 2004; Chapter 1; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Managing for stakeholders: Trade-offs or value creation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.; Maer-Matei, M.M.; Mocanu, C.; Zamfir, A.M. Key Drivers and Skills Needed for Innovative Companies Focused on Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y.; Tucci, C.L. Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, R.; Norton, D. The Balanced Scorecard—Measures that Drive Performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Freudenreich, B.; Saviuc, I.; Schaltegger, S.; Stock, M. Sustainability-Oriented Business Model Assessment—A Conceptual Foundation. In Analytics, Innovation and Excellence-Driven Enterprise Sustainability, 1st ed.; Edgeman, R., Carayannis, E., Sindakis, S., Eds.; Palgrave: Houndmills, UK, 2017; Chapter 7; pp. 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 133, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard—Linking Sustainability management to Business Strategy. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. Managing Materiality: A Preliminary Examination of the Adoption of the New GRI G4 Guidelines on Materiality within the Business Community. J. Public Aff. 2016, 16, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starik, M.; Marcus, A. Introduction to the Special Research Forum on the Management of Organizations in the Natural Environment: A Field Emerging from Multiple Paths, With Many Challenges Ahead. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 43, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Reichart, J. The Environment as a Stakeholder? A Fairness-Based Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACCA Global. 2013 ACCA, Flora & Fauna International and KPMG LLP. Identifying Natural Capital Risk and Materiality. Available online: https://www.accaglobal.com/gb/en/technical-activities/technical-resources-search/2014/january/identifying-natural-capital-risk-and-materiality.html (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Llach, J.; Marimon, F. A Closer Look at the ‘Global Reporting Initiative’ Sustainability Reporting as a Tool to Implement Environmental and Social Policies: A Worldwide Sector Analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 318–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, P.; Connole, H.; Kraut, M. The efficacy of voluntary disclosure: A study of water disclosure by mining companies using the global reporting initiative framework. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2015, 18, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Marimon, F.; Alonso-Almeida, M.D.; Rodríguez, M.D.; Alejandro, K.A.C. The worldwide diffusion of the global reporting initiative: What is the point? J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toppinen, A.; Li, N.; Tuppura, A.; Xiong, Y. Corporate Responsibility and Strategic Groups in the Forest-based Industry: Exploratory Analysis based on the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Framework. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Ghiron, N.L.; Menichini, T. Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 1016–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ouvrard, S.; Jasimuddin, S.M.; Spiga, A. Does Sustainability Push to Reshape Business Models? Evidence from the European Wine Industry. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson-Rea, M.; Brodie, R.J.; Sima, H. The plurality of co-existing business models: Investigating the complexity of value drivers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, K.L.; Burritt, R.L. Critical environmental concerns in wine production: An integrative review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, O.; Galbeaza, M.A.; Bănacu, C.S. Assessing the Sustainability of the Wine Industry in Terms of Investment. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Cullen, R.; Wratten, S.D.; Fountain, J. Consumer attitudes regarding environmentally sustainable wine: An exploratory study of the New Zealand marketplace. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dania, W.A.P.; Xing, K.; Amer, Y. Collaboration behavioural factors for sustainable agri-food supply chains: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Discovering the future of the case study. Method in evaluation research. Eval. Pract. 1994, 15, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; McManus, S.E. Methodological fit in management field research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1155–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20159839 (accessed on 5 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bolis, I.; Brunoro, C.M.; Sznelwar, L.I. Work for sustainability: Case studies of Brazilian companies. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 57, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, J.F. Case studies in organizational research. In Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research, 1st ed.; Cassel, C., Symon, G., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1995; pp. 208–229. [Google Scholar]

- Viña Concha y Toro 2020a. Sustainability Report 2017. Available online: https://conchaytoro.com/content/uploads/2021/01/REPORTE-VCT-2017_ENG.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Viña Concha y Toro 2020b. Sustainability Report 2018. Available online: https://conchaytoro.com/content/uploads/2021/01/REPORTE-VCT-2018_ENG.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Viña Concha y Toro 2020c. Sustainability Report 2019. Available online: https://conchaytoro.com/content/uploads/2021/01/REPORTE-VCT-2019_ENG.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Beck, A.C.; Campbell, D.; Shrives, P.J. Content analysis in environmental reporting research: Enrichment and rehearsal of the method in a British–German context. Br. Account. Rev. 2010, 42, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl-Davies, D.M.; Brennan, N.M. Discretionary disclosure strategies in corporate narratives: Incremental information or impression management? J. Account. Lit. 2007, 27, 116–196. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10197/2907 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Guidry, R.P.; Patten, D.M. Market reactions to the first-time issuance of corporate sustainability reports. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2010, 1, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact Management Project. Statement of Intent to Work Together towards Comprehensive Corporate Reporting. 2020. Available online: https://impactmanagementproject.com/structured-network/statement-of-intent-to-work-together-towards-comprehensive-corporate-reporting/ (accessed on 11 December 2020).

| Material Themes in MM | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|

| First prioritisation | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Second prioritisation | 8 | 13 | 2 |

| Third prioritisation | 1 | 6 | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geldres-Weiss, V.V.; Gambetta, N.; Massa, N.P.; Geldres-Weiss, S.L. Materiality Matrix Use in Aligning and Determining a Firm’s Sustainable Business Model Archetype and Triple Bottom Line Impact on Stakeholders. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031065

Geldres-Weiss VV, Gambetta N, Massa NP, Geldres-Weiss SL. Materiality Matrix Use in Aligning and Determining a Firm’s Sustainable Business Model Archetype and Triple Bottom Line Impact on Stakeholders. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031065

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeldres-Weiss, Valeska V., Nicolás Gambetta, Nathaniel P. Massa, and Skania L. Geldres-Weiss. 2021. "Materiality Matrix Use in Aligning and Determining a Firm’s Sustainable Business Model Archetype and Triple Bottom Line Impact on Stakeholders" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031065

APA StyleGeldres-Weiss, V. V., Gambetta, N., Massa, N. P., & Geldres-Weiss, S. L. (2021). Materiality Matrix Use in Aligning and Determining a Firm’s Sustainable Business Model Archetype and Triple Bottom Line Impact on Stakeholders. Sustainability, 13(3), 1065. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031065