A New Approach for Assessing Secure and Vulnerable Areas in Central Urban Neighborhoods Based on Social-Groups’ Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Secured and Walkable Environments

1.2. Evaluation and Measurement

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology for the Security Analysis Model and Model Assessment

Building Blocks of the Security Model and Evaluation Process

- Conducting a literature review—a comprehensive literature review was conducted for identifying urban elements and settings that affect personal security in the built environment.

- Selected quantifiable urban elements—through the literature review, a list was drawn of prominent urban elements and urban settings that are most influential to personal security in urban areas.

- Determining specific scale for each urban element—each selected urban element was weighted and measured individually in accordance to its influence on urban vulnerability and security of the built environment. Each urban element was first measured individually using GIS software.

- Superposition analysis and case study analysis—the analysis of the measured individual urban elements were integrated into a combined index, implemented on one case study, the Hadar neighborhood.

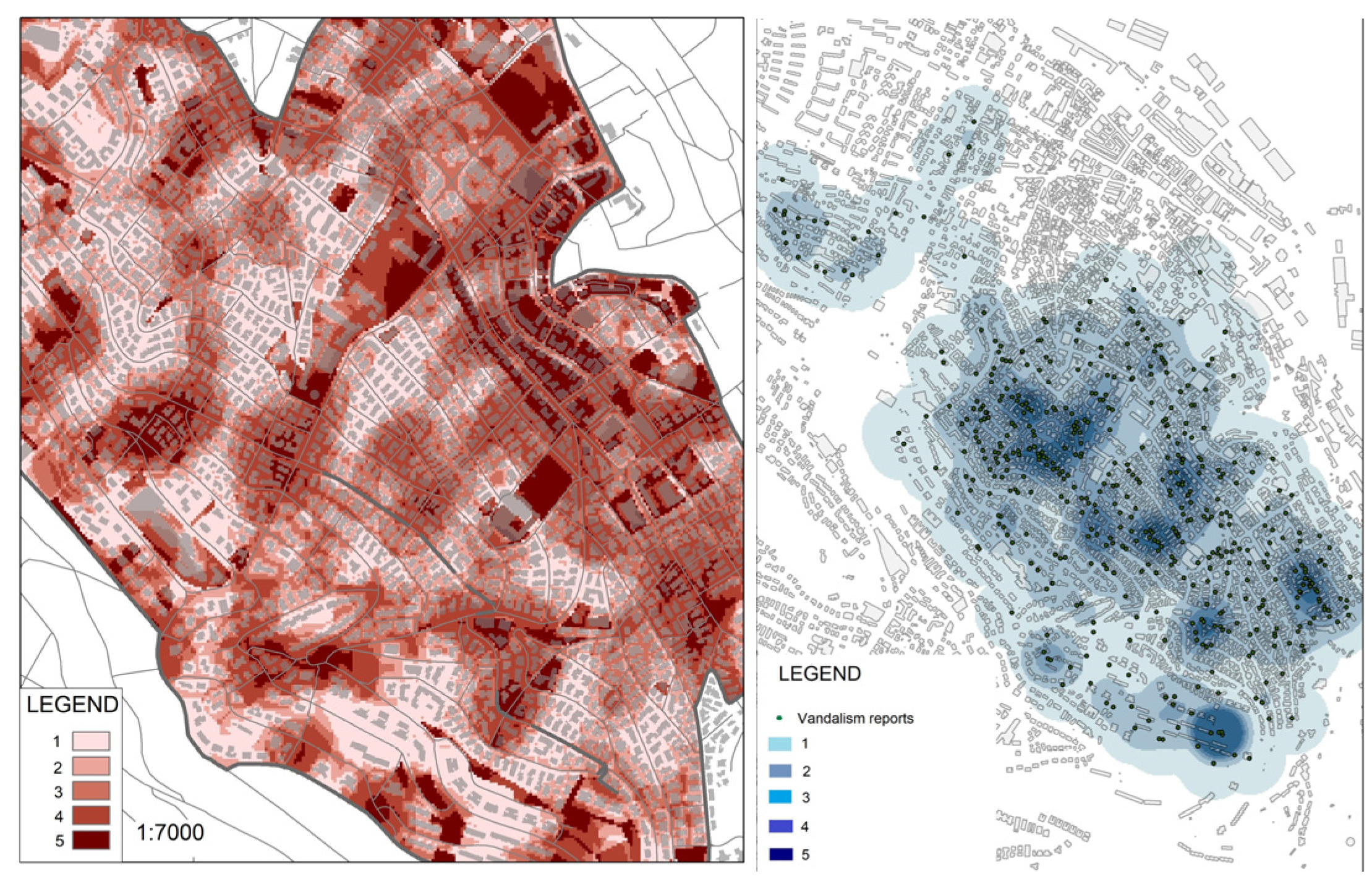

- Evaluation and validation—security assessment results were evaluated based on interviews of different social group representatives in Hadar. The results of these qualitative analyses were marked on maps and analyzed using GIS analysis tools. The validation method referred to was based on vandalism hotspot analysis for the Haifa municipality data. The results of both approaches were evaluated in comparison to the security analysis results and refined the model for better understanding the locations of unsecure and secure walkable routes and streets in Hadar.

4. Model Development and Demonstration

4.1. Urban Elements Identification and the Security Analysis

- Streetlights (urban elements). One of the main influential urban elements on personal security in the city at night are the streetlights [62]. Jacobs [13] argues that places with streetlights encourage positive occurrences and produce a positive effect of “eyes on the street”. Greenberg et al. [65] argued that street lights are the physical traits that increase the sense of security, and Llewelyn et al. [25] stated that street lights can be quantitatively measured by using a variety of geometrical terms, or by counting them at the site.

- Measuring proximity in the city (aspects of urban context). Proximity affects security in the built environment. The degree of the proximity and the distance between buildings, between the street and the buildings, and distance to emergency services, influences the safe city [12]. Shach-Pinsly [4] measured visual privacy in the built environment using distances between buildings. The level of personal security is inverted to the measured level of privacy; therefore, proximity increases the sense of security. An important element of the city’s reading is the territorial issue. Gehl [16] argued that clear definition between different urban territories, private or public, defines a safe city. Llewelyn et al. [25] determined that one of the five components that have significant impact on crime prevention and personal safety is territorial delimitation.

- Land uses and mixed uses (land uses). Mixed uses have significant impact on security in the built environment. Jacobs [13] criticized that separation of uses leads to the disintegration of urban communities and causes urban alienation, resulting in deterioration of personal security and quality of life in the urban environment. Greenberg et al. [65] pointed out that mixed land uses influence the level of crime in different neighborhoods. Cozens et al. [26] noted the importance of creating places containing active and safe mixed uses in order to deter crime. Saville and Cleveland [62] noted that parking lots are essential elements in the urban landscape, but are often a place with diminished sense of security. Clarke and Mayhew [66] argued that the temporary nature of public parking acts as a potential place for theft.

- Numbers of nodes (integration/segregation). Street intersections influence crime levels according to Weisburd et al. [67]. Van Nes and ZhaoHui [64] studied connectivity of intersections by examining different types of intersections using the spatial syntax method and concluded that intersections of more than two streets in a particular area improves connectivity and reduces crime potential.

- Surveillance (aspects related to human behavior). Surveillance as reflected by visual distance manifests the opposite of privacy. Schweitzer et al. [68] pointed out the influence of the arrangement of urban elements in the built environment on natural surveillance. The visible distance between individuals affects the level of safety, and based on this assumption, Gehl [16] developed a key index of visibility. Llewelyn et al. [25] determined that among the five fundamental components for increasing personal security are to observe and the subject of observation. The notion of observing and being observed lay at the basis of the CPTED concept, as one of its four strategies of action for natural surveillance [26,27,62].

4.2. The Security Sensitivity Index Development

- Mixed uses—rated according to the literature review, evaluates whether the land use is mixed or homogenous;

- Proximity of buildings—distance between buildings, which shows density of the built environment;

- Proximity from junctions—distance between street intersections;

- Connectivity between intersections—number of streets that intersect in one junction;

- Streetlights—number of streetlights in a given area (a dense cluster of streetlights enhances security);

- Walkway paths—are narrow passageway and alleys that lay between the streets and buildings in many locations in Hadar. This walkway path usage is affected by the walkway path width and the ease of entrance to and exit from walkway paths (this aspect was examined as part of the interviews with the social groups).

4.3. GIS Base Analysis and Scale Design for Each Urban Variable

5. Findings and Results

Findings and Results—Superposition Maps for Daytime and Nighttime Analysis

6. Validation Methods

6.1. Assessing Street Crimes with Vandalism Map Calls to the 106 Call Center

6.2. Urban Survey, Interview Design, and Mapping

6.2.1. Designing the Weighted Scale Table

6.2.2. Interview and Mapping Analysis Results

7. Integrative Maps

8. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahlbrandt, R. Neighborhoods, People, and Community; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brasington, D.M.; Hite, D. Demand for environmental quality: A spatial hedonic analysis. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2005, 35, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Song, X. The impact of environmental regulation, shadow economy, and corruption on environmental quality: Theory and empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D. Visual exposure and visual openness analysis model used as evaluation tool during the urban design development process. J. Urban. 2010, 3, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, F.; Cambra, P.; Gonçalves, A.B. Measuring walkability for distinct pedestrian groups with a participatory assessment method: A case study in Lisbon. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capeluto, I.G.; Plotnikov, B. A method for the generation of climate-based, context-dependent parametric solar envelopes. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2017, 60, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D.; Capeluto, I.G. From Form-Based to PerFormance Based Codes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.P.; Faber, B.J. Integration of Landsat Thematic Mapper and census data for quality of life assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 1997, 62, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, U.C.; Hofmann, P.; Willhauck, G.; Lingenfelder, I.; Heynen, M. Multi-resolution, object-oriented fuzzy analysis of remote sensing data for GIS-ready information. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2004, 58, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Yin, G.; Johnson, B.A. Deep learning in remote sensing applications: A meta-analysis and review. Isprs J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 152, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D. Measuring Security in the Built Environment: Evaluating Urban Vulnerability in a Human-Scale Urban Form. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 191, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D.; Ganor, T. Security Sensitivity Index: Evaluating urban vulnerability. Proc. ICE Urban Des. Plan. 2015, 168, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Defensible Space; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1972; p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sarkissian, W. Housing as If People Mattered: Site Design Guidelines for the Planning of Medium-Density Family Housing; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C.; Pavan, V.M. Evaluating urban quality: Indicators and assessment tools for smart sustainable cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Virta, S. Governing urban security in Finland: Towards the ‘European model’. Eur. J. Criminol. 2013, 10, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R.G. Holistic strategy for urban security. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2004, 10, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jore, S.H. Ontological and epistemological challenges of measuring the effectiveness of urban counterterrorism measures. Secur. J. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hillier, B. Can streets be made safe? Urban Des. Int. 2004, 9, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Nes, A. Space and crime in Dutch built environments. In Proceeding of the 6th International Symposium on Space Syntax, Istanbul, Turkey, 12–15 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, S. Housing layout and crime vulnerability. Urban Des. Int. 2000, 5, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland, H. Perceptions of Privacy & Density in Housing; Design for Homes Popular Housing Research; Mulholland Research & Consulting: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Llewelyn-Davies (Firm); Holden McAllister Partnership. Safer Places: The Planning System and Crime Prevention; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cozens, P.M.; Saville, G.; Hillier, D. Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED): A review and modern bibliography. Prop. Manag. 2005, 23, 328–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cozens, P.; Love, T. A review and current status of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED). J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohl, C.C. New urbanism and the city: Potential applications and implications for distressed inner-city neighborhoods. Hous. Policy Debate 2000, 11, 761–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congress for the New Urbanism. Charter of the New Urbanism. CNU. 2001. (New York City, New York, 7–10 June 2001). Available online: http://www.cnu.org/charter (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Knaap, G.; Talen, E. New urbanism and smart growth: A few words from the academy. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2005, 28, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atreya, A.; Kunreuther, H. Measuring Community Resilience: The Role of the Community Rating System (CRS). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2788230 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2788230 (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D. Do sustainable community rating systems address resilience? Cities 2019, 93, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, M.; Steele, W.; Rickards, L.; Fünfgeld, H. Keywords in planning: What do we mean by ‘community resilience’? Int. Plan. Stud. 2016, 21, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, K.M.; Abdelmonem, M.G.; Selim, G. Walkability in historic urban spaces: Testing the safety and security in Martyrs’ Square in Tripoli. Int. J. Archit. Res. Archnet-Ijar 2017, 11, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Southworth, M. Designing the walkable city. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2005, 131, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Hassan, N.R.A.; Bilyamin, S.F.I. Walkable environment in increasing the liveability of a city. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. Behav. Sci. 2012, 50, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewing, R.; Clemente, O. Measuring Urban Design: Metrics for Livable Places; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth, A. What is a walkable place? The walkability debate in urban design. Urban Des. Int. 2015, 20, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D. Community design and individual wellbeing: The multiple impacts of the built environment on public health. In Division of Research Coordination, Planning and Translation; League, C.A., Dearry, A., Eds.; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2004; pp. 55–61. Available online: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/news/events/pastmtg/assets/docs_n_z/supplementary_informationoverviewfrank_508.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Fava, G.A.; Ruini, C. Well-being therapy. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 7108–7109. [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Vernez-Moudon, A.; Reis, R.; Turrell, G.; Dannenberg, A.L.; Badland, H.; Owen, N. City planning and population health: A global challenge. Lancet 2016, 388, 2912–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, D.W.; Yoon, D.K.; Lee, J. The impact of neighborhood permeability on residential burglary risk: A case study in Seattle, USA. Cities 2018, 82, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Advocacy for the compact, mixed-use and walkable city: Designing smart and climate resilient places. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porębska, A.; Rizzi, P.; Otsuki, S.; Shirotsuki, M. Walkability and Resilience: A Qualitative Approach to Design for Risk Reduction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rogers, S.H.; Gardner, K.H.; Carlson, C.H. Social capital and walkability as social aspects of sustainability. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3473–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilderbloom, J.I.; Riggs, W.W.; Meares, W.L. Does walkability matter? An examination of walkability’s impact on housing values, foreclosures and crime. Cities 2015, 42, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walk Score. July 2007. Available online: https://www.walkscore.com/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Sandalack, B.A.; Alaniz Uribe, F.G.; Eshghzadeh Zanjani, A.; Shiell, A.; McCormack, G.R.; Doyle-Baker, P.K. Neighbourhood type and walkshed size. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2013, 6, 236–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkshed. 2010. Available online: http://www.walkshed.org/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Betts, B. Software reviews-Apps for the smart city [Reviews Software]. Eng. Technol. 2016, 11, 82–83. [Google Scholar]

- Walkonomics. 2011. Available online: https://walkonomics.com/ (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Wimbardana, R.; Tarigan, A.K.; Sagala, S. Does a Pedestrian Environment Promote Walkability? Auditing a Pedestrian Environment Using the Pedestrian Environmental Data Scan Instrument. J. Reg. City Plan. 2018, 29, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Azzali, S.; Janssen, P.; Stouffs, R. Design for walkable neighbourhoods in Singapore using Form-based Codes. In Proceedings of the 11th International Forum on Urbanism: Reframing Urban Resilience Implementation, Barcelona, Spain, 10–12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yang, P.P.; Chen, H.; Murakami, D.; Ilmola, L. Measuring quality of walkable urban environment through experiential modeling. In Urban Systems Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 373–392. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, L.G.N.; Deritei, D.; Vancsó, A.; Vasarhelyi, O. Quantifying Life Quality as Walkability on Urban Networks: The Case of Budapest. In International Conference on Complex Networks and Their Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 905–918. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, C.E.; Gibbon, H.M.F.; Nurse, A.M. Social Inequality: Forms, Causes, and Consequences; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aharon-Gutman, M.; Burg, D. How 3D visualization can help us understand spatial inequality: On social distance and crime. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, U. Spatial Inequality and Urban Poverty Traps; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kilroy, A. Intra-Urban Spatial Inequality: Cities as” Urban Regions”; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Duan, D. Spatial inequality of bus transit dependence on urban streets and its relationships with socioeconomic intensities: A tale of two megacities in China. J. Transp. Geogr. 2020, 86, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, P.; Campanera, J.; Nobajas, A. Quality of life and spatial inequality in London. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 21, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saville, G.; Cleveland, G. An introduction to 2nd Generation CPTED: Part 1. Cpted Perspect. 2003, 6, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Talen, E. Design for diversity: Evaluating the context of socially mixed neighbourhoods. J. Urban Des. 2006, 11, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nes, A.; ZhaoHui, S. Network typology, junction typology and spatial configuration and their impacts on street vitality in Singapore. In Proceedings of the 7th International Space Syntax Symposium, Stockholm, Sweden, 8–10 June 2009; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, S.W.; Rohe, W.M.; Williams, J.R. Safety in urban neighborhoods: A comparison of physical characteristics and informal territorial control in high and low crime neighborhoods. Popul. Environ. 1982, 5, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.V.; Weisburd, D. Diffusion of crime control benefits: Observations on the reverse of displacement. Crime Prev. Stud. 1994, 2, 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- Weisburd, D.; Groff, E.R.; Yang, S.M. The Criminology of Place: Street Segments and Our Understanding of the Crime Problem; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Mackin, J.R. The impact of the built environment on crime and fear of crime in urban neighborhoods. J. Urban Technol. 1999, 6, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shach-Pinsly, D.; Fisher-Gewirtzman, D.; Burt, M. Visual Exposure & Visual Openness integrated approach and comparative evaluation. J. Urban Des. 2011, 16, 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrany, M. Subjective Housing Density and the Housing Context. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Architecture and Town Planning, The Technion–IIT, Haifa, Israel, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Devlin, A.S. Vandalism: Environmental and social factors. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2003, 44, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.D.; Baron, R.M. An equity-based model of vandalism. Popul. Environ. 1982, 5, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMore, S.W.; Fisher, J.D.; Baron, R.M. The Equity-Control Model as a Predictor of Vandalism among College Students 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, A.P. The Ecology of Aggression; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- E”SRI” Documentation. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/tool-reference/spatial-analyst/how-kernel-density-works.htm (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Levine, N. CrimeStat II: A Spatial Statistics Program for the Analysis of Crime Incident Locations, Part I; The U.S National Institute of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

| Theme | Most Secured | Least Secured | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Uses | Most Mixed 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | Least Mixed 1 | |||||

| Street Lights | Many 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | Few 1 | |||||

| Building typology proximity | 0 < X < 5 m | 5 < X < 10 m | 10 < X < 15 m | 15 < X < 20 m | 20 < X < 25 m | 25 < X < 30 m | 30 < X < 35 m | 35 < X < 40 m | 40 < X < 50 m | X > 50 m |

| Distance between junctions | 0 < X < 5 m | 5 < X < 10 m | 10 < X < 15 m | 15 < X < 20 m | 20 < X < 25 m | 25 < X < 30 m | 30 < X < 35 m | 35 < X < 40 m | 40 < X < 50 m | X > 50 m |

| Walkway paths | 0 < X < 5 m | 5 < X < 10 m | 10 < X < 15 m | 15 < X < 20 m | 20 < X < 25 m | 25 < X < 30 m | 30 < X < 35 m | 35 < X < 40 m | 40 < X < 50 m | X > 50 m |

| Number of intersections | Many streets (5) | 4 | 3 | 2 | Few streets (1) | |||||

| Theme | Secured 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Not Secured 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime Security | Feeling secured | Feeling less secured | Moderate sense of security | Unsecured feeling | Absolute unsecured feeling |

| Nighttime Security | Feeling secured | Feeling less secured | Moderate sense of security | Unsecured feeling | Absolute unsecured feeling |

| Vegetation | Substantial vegetation | Moderate vegetation | Lack of vegetation | ||

| lighting | Sufficient lighting | Moderate lighting | Lack of lighting |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shach-Pinsly, D.; Ganor, T. A New Approach for Assessing Secure and Vulnerable Areas in Central Urban Neighborhoods Based on Social-Groups’ Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031174

Shach-Pinsly D, Ganor T. A New Approach for Assessing Secure and Vulnerable Areas in Central Urban Neighborhoods Based on Social-Groups’ Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031174

Chicago/Turabian StyleShach-Pinsly, Dalit, and Tamar Ganor. 2021. "A New Approach for Assessing Secure and Vulnerable Areas in Central Urban Neighborhoods Based on Social-Groups’ Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031174

APA StyleShach-Pinsly, D., & Ganor, T. (2021). A New Approach for Assessing Secure and Vulnerable Areas in Central Urban Neighborhoods Based on Social-Groups’ Analysis. Sustainability, 13(3), 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031174