4.3. Reliability and Validity Test

This article uses Cronbach’s Alpha index to test reliability. Generally speaking, Cronbach’s Alpha index is greater than 0.70, indicating high reliability. The results in

Table 3 show that the reliability of all variables in this study is greater than 0.790. Therefore, the questionnaire used in this study has acceptable reliability.

The measurement of validity can be divided into content validity, aggregate validity and discriminative validity. The scale used in this article is based on existing theories. It has been relatively mature in the field and has been used by many scholars. On this basis, in the process of questionnaire design, many scholars and scholars in the field Consumers have conducted in-depth discussions and modifications, so the content validity of the scale is high.

Convergent validity is also called convergent validity or internal consistency validity, which is used to analyze whether each item reflects the same latent variable. The test results are shown in

Table 4. It can be seen from

Table 4 that the standardized factor loadings of all variables in this study are greater than 0.770, the combined reliability is greater than 0.835, and the average refined variance is greater than 0.561, indicating that the validity of the scale of this study is acceptable.

Discrimination validity is used to analyze and verify whether two different variables are statistically different. According to the results in

Table 2, the square root of the average refined variance of all variables is greater than the correlation coefficient between the variable itself and other variables. According to Hair et al. [

53], the discriminative validity of the scale used in this study can be tested.

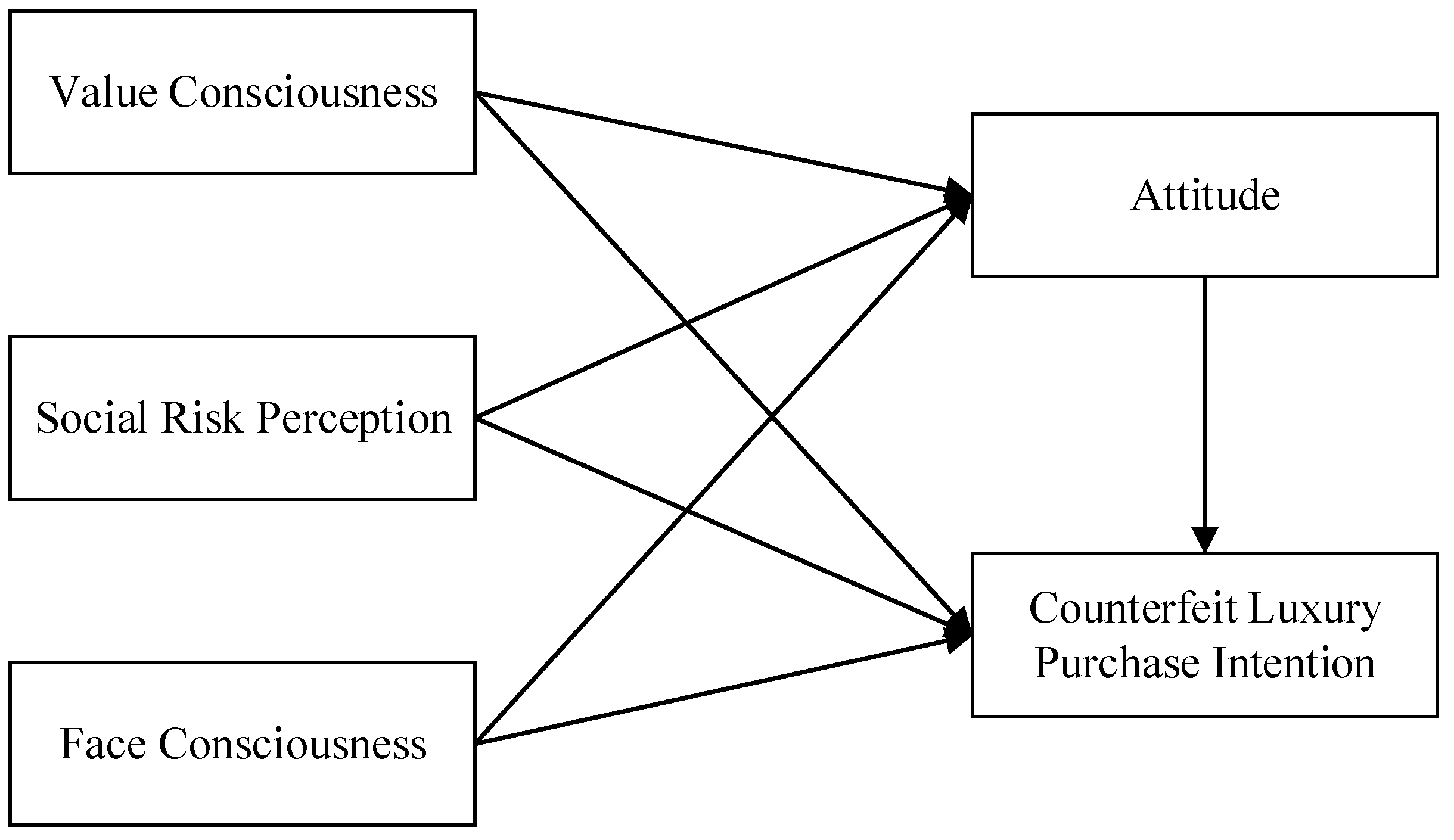

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

This study uses statistical analysis software SPSS 26.0 to analyze the main variables involved in this study, including value consciousness, social risk perception, decent awareness, square terms of face consciousness, attitude, and purchase intention using hierarchical regression methods. The results are as follows

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Model 1 showed the regression results of four control variables (gender, age, education, and income) and luxury counterfeit purchase intention. The results suggested that gender and income exerted significant influence on counterfeit luxury purchase intention. Compared with male consumers, female consumers presented a higher intent to purchase counterfeit luxury products. As for the income, results indicated that consumers with a lower level of income tended to consume counterfeit luxury products more.

On the basics of model 1, model 2 added value consciousness. Regression analysis results show that consumers’ value consciousness has a significant positive impact on the purchase intention of counterfeit luxury products (r = 0.123, p < 0.05), and H1 was supported. When the consumer’s value consciousness is higher, then the consumer’s willingness to buy counterfeit luxury products is stronger.

On the basics of Model 1, Model 3 added social risk perception. Regression analysis results show that consumers’ perception of social risks has a significant negative impact on the purchase intention of counterfeit luxury products (r = −0.229, p < 0.001), and H2 was supported. When the consumer’s perception of social risks is higher, then the willingness to buy counterfeit luxury products is weaker.

On the basics of model 1, model 4 and model 5 are formed by adding the face consciousness and face consciousness square step by step. The results show that the ace consciousness square is significantly negatively correlated with consumers’ willingness to buy counterfeit luxury products (r = −0.215, p < 0.001), indicating that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between Face consciousness and purchase intention, that is, having a low level or having consumers with a high level of face consciousness show a lower willingness to purchase counterfeit luxury products, and H3 was supported.

Based on the research of Baron and Kenny [

54], this article examines the mediating role of attitudes between value consciousness, social risk perception and the purchase intention of counterfeit luxury products. Model 6–Model 10 with Attitude are the dependent variables, Model 11–Model 14 with Luxury counterfeit purchase intention are the dependent variables.

On the basics of model 6, model 7 added value consciousness. The results show that value consciousness has a significant positive impact on attitude (r = 0.190, p < 0.001). The results of Model 11 show that the attitude exerted a significant positive effect on the purchase intention (r = 0.702, p < 0.001). The results of Model 12 showed that the value and significance level of value consciousness to purchase intention, were reduced after adding attitude. The value changes from r = 0.123 (p < 0.05, model 2) to r = −0.010 (p > 0.1, model 12), while the influence of attitude on purchase intention is still significant (r = 0.699, p < 0.001). Therefore, based on the above data analysis results, the mediating effect of attitude between value consciousness and purchase intention is supported by the result, and H4 was passed.

On the basics of model 6, model 8 added social risk perception. The results show that social risk perception has a significant negative impact on attitude (r = −0.245, p < 0.001). The results of Model 11 show that attitude also has a significant positive effect on purchase intention (r = 0.702, p < 0.001). The results of Model 13 show that the regression coefficient and significance level of social risk perception on purchase intention are reduced after adding attitude, and the regression coefficient of social risk perception is changed from −0.229 (p < 0.001, model 3) to −0.043 (p < 0.05, model 13), and the influence of attitude on purchase intention is still significant (r = 0.684, p < 0.001). Therefore, based on the above data analysis results, the mediating effect of attitude between social risk perception and purchase intention is supported by the data, and H5 was passed.

As for H6, Edwards and Lambert [

55] consider that the method of using Baron and Kenny [

54] to test the mediation effect will not accurately reflect the curvilinear relationship between variables, nor can it effectively reveal the effect path of the mediation variable between the independent variable and the dependent variable. Therefore, Edwards and Lambert [

55] developed moderating path analysis method to test for mediation effects. After adding attitude as an intermediary variable and the interaction term between face consciousness and attitude in Model 14, the square term of face consciousness has a negative significant effect on purchase intention (r = −0.136,

p < 0.05), which indicates there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between face consciousness and purchase intention. The interaction term of face consciousness and attitude has no significant effect on purchase intention (r = 0.172,

p > 0.1), indicating that the relationship between attitude and consumers’ willingness to purchase counterfeit luxury products is not affected by the contingency of face consciousness. Based on the above results, there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between consumers’ face consciousness and the purchase intention of counterfeit luxury products, and the relationship is mediated by attitude, therefore, H6 was passed.

Based on the results of the above analysis, the test results of the hypothesis proposed in this study are shown in

Table 7.

4.5. Robustness Test

Most scholars now use the stepwise regression test procedure proposed by Baron and Kenny [

54] when testing the mediating effect of the model, however, the stepwise test method proposed by Preacher and Hayes [

56] is not suitable for testing for multiple intermediary models. Hayes et al. [

57] also believe that the method of Baron et al. [

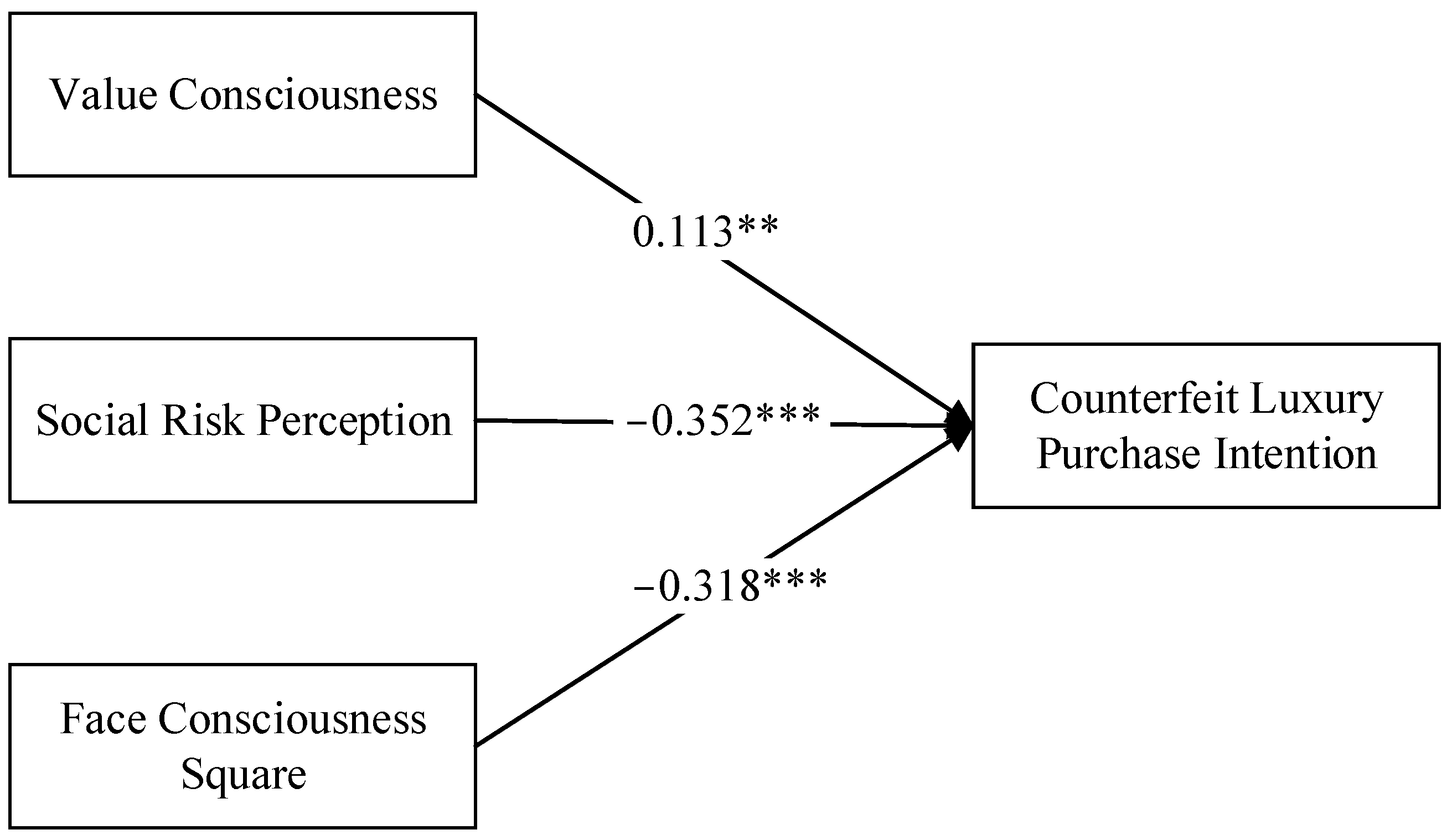

54] testing, the mediation effect cannot clearly reveal the mediation effect of a third-party variable between the independent variable and the dependent variable. Therefore, this study also uses structural equation analysis (SEM) and Bootstrapping to verify the hypothesis of this study. First, the examined results of main effects between value consciousness, social risk perception, face consciousness square and counterfeit luxury purchase intention is shown in

Figure 2. Then, the examined results of the model with attitude added is shown in

Figure 3.

The path coefficient of the influence of value consciousness on the purchase intention is 0.113, and p < 0.05, indicating that consumers’ value consciousness can significantly positively predict consumers’ purchase intention of counterfeit luxury products, that is, the value of consumers. Therefore, the higher the awareness, the stronger the willingness to buy counterfeit luxury products. H1 was passed. The path coefficient of consumers’ perception of social risk on the purchase intention is −0.352, and p < 0.001, indicating that consumers’ perception of social risk has a significant negative impact on purchase intention, that is, consumers’ perception of social risk. The higher the value, the weaker the willingness to buy counterfeit luxury products. H2 was passed. The path coefficient of the face consciousness square on the purchase intention of counterfeit luxury products is −0.318, and p < 0.001, indicating that there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between face consciousness and purchase intention, H3 was passed.

The results of the structural equation analysis and Bootstrap test are shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 8, respectively to test the mediating role of attitude. Repeated random sampling method was used to extract 5000 Bootstrap samples from the original data (N = 412). By querying the 2.5th percentile and the 97.5th percentile, the 95% confidence interval of the intermediate effect is estimated. If the 95% confidence interval of the measured path coefficient does not contain 0, it indicates that the mediating effect is significant.

It can be seen from

Figure 3 that value consciousness exerts a significant effect on attitude, while the direct effect is not significant. In addition, the 95% confidence interval of the path that value consciousness affects purchase intention through attitude is positive, and does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect of attitude between value consciousness and purchase intention is significant. Thus, it can be seen attitude plays a complete intermediary role in the influence of value consciousness on purchase intention, and H4 was passed.

Social risk perception exerts a significant effect on attitude and purchase intention. In addition, the 95% confidence interval of the path that social risk perception affects purchase intention through attitude is negative, and does not include 0, indicating that the mediating effect of attitude between social risk perception and purchase intention is significant. Therefore, we can conclude that attitude plays a part intermediary role in the influence of social risk perception on purchase intention, and H5 was passed.

Face consciousness square exerts a significant effect on attitude and purchase intention. In addition, the 95% confidence interval of the path that the square term of face consciousness affects purchase intention through attitude is negative, and 0 is not included, indicating that the mediating effect of attitude between the Face consciousness square and purchase intention is significant. Therefore, we can conclude that attitude have a mediating effect on the inverted U-shaped relationship between face consciousness and counterfeit luxury purchase intentions, thus H6 was passed. Therefore, the research results in this article are robust.