The Strengths and Weaknesses of Pacific Islands Plastic Pollution Policy Frameworks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Melanesia: The Republic of Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu

- -

- Polynesia: The Independent State of Samoa, the Kingdom of Tonga, Tuvalu

- -

- Micronesia: The Republic of Kiribati, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Republic of Palau.

- Keyword search of documents. Documents were searched for the following terms: ‘waste’, ‘plastic’, ‘refuse’, ‘garbage’, ‘litter’, ‘pollution’, ‘microplastic’, ‘marine debris’, ‘hazardous waste’, ‘emission’, and ‘contaminant’ for references to plastic pollution.

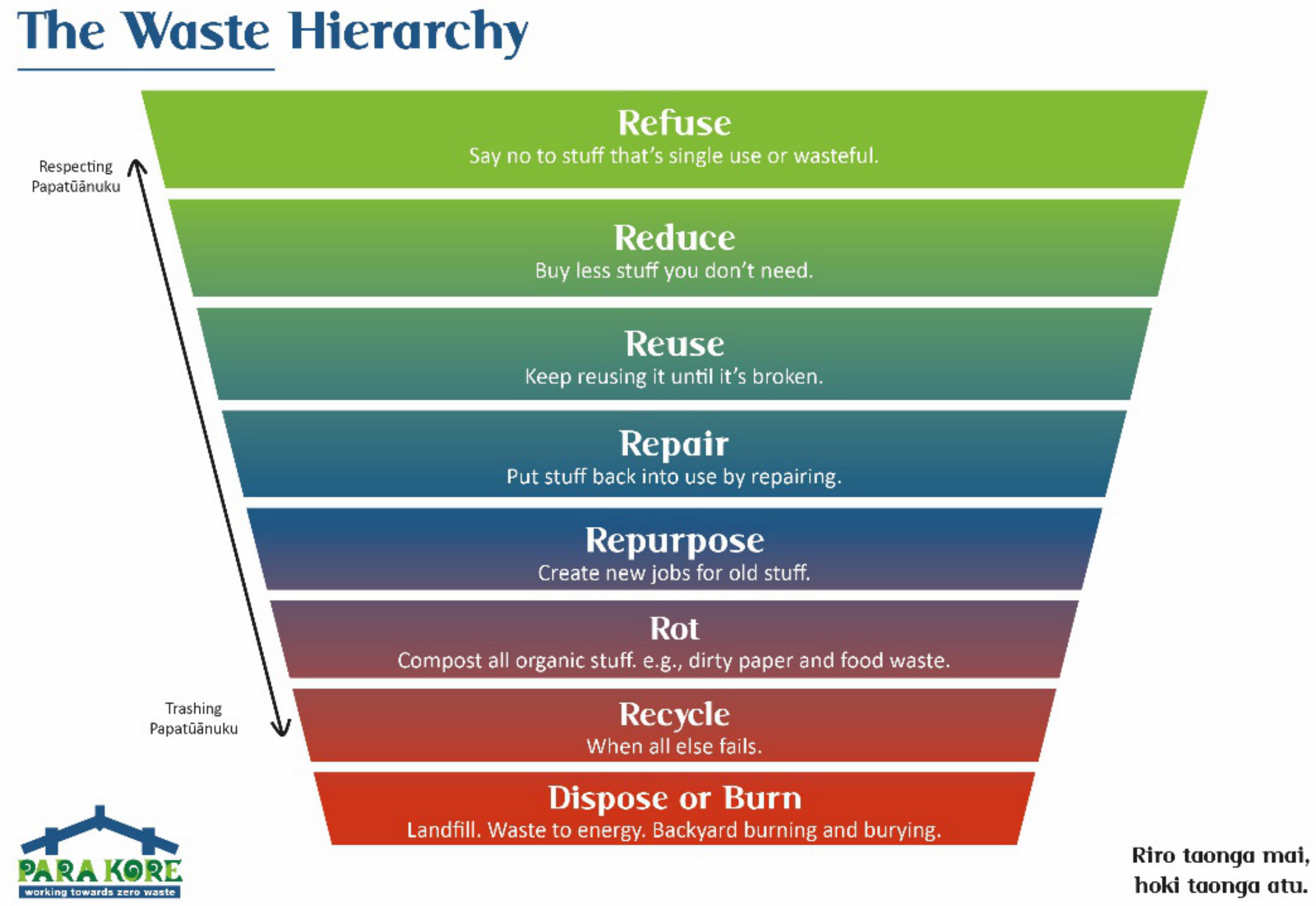

- Documents were reviewed to determine whether its instruments and mechanisms for plastic pollution focused on the top of the waste hierarchy: refuse, rethink, reduce, redesign, and reuse. From this, a set of documents were determined ‘key’ to preventing plastic pollution in each country.

- Next, a granular thematic analysis of the key documents was undertaken using the key words and themes derived from the analytical framework (Table 1). Synonyms and synonymic phrases in the themes were examined for their application within and across national legislation, policies, and plans.

- Based on the definitions provided in the analytical framework (Table 1), green indicates explicit mention of the theme in the document, yellow indicates that the document either partially includes the theme or that it is inferred and red indicates that that the theme is absent in the document.

- Country delegates were emailed to request validation of the selected documents and the study was validated through an internal peer review process.

3. Results

3.1. Global Objectives

3.1.1. Vertical Integration

3.1.2. Horizontal Integration

3.1.3. Protection of Human Health

3.1.4. Climate Change

3.1.5. Waste Hierarchy

3.2. Prevention

3.3. Management

3.4. Microplastics

3.5. Standardisation

4. Key Recommendations

4.1. Global Objectives

4.2. Waste Prevention

4.3. Waste Management

4.4. Standardisation

4.5. Microplastics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Legislation & Regulations |

| The Environment Management Act 2005 (EMA) |

| Marine (Pollution Prevention and Management) Regulations 2014 |

| Environmental Management (Container Deposit) Regulations 2011 |

| Environment Management Act 2005 (Amendment 24 June 2019 come into force 1 January 2020) |

| Environment Management (Waste Disposal and Recycling) Regulations 2007 |

| Litter Amendment Decree (2010) |

| Environmental Management (EIA Process) Regulations 2007 |

| Litter Promulgation 2008 |

| The Environment and Climate Change Adaption Levy on Prescribed Services, Items and Income (ECAL), 2017 |

| Environment & Climate Adaptation Levy (Plastic Bags) Regulations 2017 |

| Customs Tariff Act 2009 (as 8th June 2019) (should be read as one with the Customs Act 1986) |

| Customs (Prohibited Imports and Exports) Regulations 1986 (as at 8 June 2019) |

| Litter Act 2008 (as at 1 August 2018) |

| Public Health Act 1935 (Chapter 111) |

| Public Health Regulations 1937 (as at 1 August 2018) [PHA 128]. |

| Public Health and Sanitary Services Regulations 1941 |

| iTaukei Affairs Act 1944 (as at 9 March 2012) |

| iTaukei Affairs (Provincial Councils) Regulations 1996 (as at 1 December 2016) |

| Biosecurity Act 2008 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| Container Deposit Legislation and Refund System for Fiji (CDL) |

| Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011–2014 |

| Climate Change and Health Strategic Action Plan 2016–2020 |

| A Green Growth Framework for Fiji: Restoring the Balance in Development that is Sustainable for Our Future (2014) |

| National Plan for Implementation of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in Fiji Islands 2006 |

| Reports |

| Fiji State of Environment Report 2013 |

| The PWC Fiji National Budget 2019–2020 |

| Towards an integrated oceans management policy for Fiji: Policy and Law Scoping Paper (2017). |

| PWC Fiji National Budget 2019–2020 |

| Solid Waste Management in the Pacific: Fiji Country Snapshot 2014 |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Environment Act 1999 |

| Environment (Amendment) Act 2007 |

| Special Fund (Waste Materials Recovery) Act 2004 |

| Deposits Order 2005 |

| Special Funds (Waste Material Recovery) Regulations 2005 |

| Local Government Act 1984 |

| Public Health Ordinance 1926 |

| Public Highways Protection Act 1989 |

| Fisheries (Amendment) Act 2017 |

| Customs Act 2019 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| Kiribati Solid Waste Management (SWM) Plan 2007 |

| Kaoki Mange! Program 2004 —Container Deposit Scheme |

| Kiribati Integrated Environment Policy (2013) |

| Kiribati Development Plan 2016–19 |

| Kiribati 20-year Vision 2016–2036 |

| Kiribati Trade Policy Framework 2017–2027 |

| Draft National Solid Waste Management Strategy (Oct 2007) (active 2008–2011) |

| Reports |

| Ninth Regional 3R Forum in Asia and the Pacific (Kiribati Country Report) |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Styrofoam cups and plates, and plastic products prohibition, and container deposit Act 2016 |

| Littering Act 1982 |

| 204: Prohibition of littering 205: Power of arrest and removal of litter |

| Prohibition of smoking (in public premises and public vehicles) Act 1986 |

| National Environmental Protection Act 1984(EPA) |

| Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations 1994 |

| Marine Water Quality Regulation 1992 |

| Solid Waste Regulation 1989 |

| Toilet Facilities and Sewage Disposal Regulations 1990 |

| The Sustainable Development Regulations 2006 |

| Fisheries Act 1997 |

| Coastal Conservation Act 1988 |

| Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations 1994 |

| Public Health, Safety and Welfare Act 1966 |

| Ministry for the Environment Act 2018 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| National Environment Management Strategy 2017–2022 |

| Kwajalein Atoll Solid Waste Management Plan 2019–2028 |

| National Energy Policy and Energy Action Plan 2016 |

| National Waste Management Strategy (in draft and has not been approved by cabinet) |

| Reports |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) Waste to Energy Report (2018) |

| Moana Taka Partnership |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Constitution 1979 |

| ‘Zero Disposable Plastic’ Policy, Executive Order No. 417 (8 August 2018) |

| Plastic Bag Use Reduction Act, RPPL No. 10–14 2017 |

| This act amended the National Code Title 11: Business and Business Regulation, Chapter 16: Recycling Program |

| The Recycling Act 2006 |

| Beverage Container Recycling Regulations 2009 |

| National Code Title 24: Environmental Protection 1999 |

| Solid Waste Management Regulations2013(Chapter 2401-31) |

| Marine & Fresh Water Quality Regulations 2013 (Chapter 2401-11) |

| Wastewater Treatment and Disposal Regulations 2019 |

| Ozone Layer Protection Regulations 2016 |

| Air Pollution Control Regulations 2013 |

| Pristine Paradise Environmental Fee, RPPL No. 10-02 2017 (Amendment) |

| Biosecurity Act 2014 (RPPL No. 9-58) |

| National Code Title 34: Public Health, Safety and Welfare 2001 |

| Environmental Health Regulations 2004 |

| Article 12 establishes minimum standards governing the operation and maintenance of solid waste storage, collection and disposal systems. |

| Toilet Facilities and WastewaterDisposal Regulations 1996 |

| National Code Title 40: Revenue and Taxation, Division 2: Unified Tax Act 1985 |

| Customs Regulations 2015 |

| National Code Title 17: Crimes (as at 2014) |

| Penal Code of the Republic of Palau, RPPL No. 9-21 2013 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| National Solid Waste Management Strategy: The Roadmap towards a Clean and Safe Palau 2017 to 2026 |

| Palau Responsible Tourism Policy Framework 2017–2021 |

| Palau National Plan for Implementation of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2013) |

| Palau Climate Change Policy 2015 |

| 2008–2015 National Solid Waste Management Plan (draft only, superseded by NSWPS 2017–2026) |

| Reports |

| Palau Review of Natural Resource and Environment Related Legislation (SPREP, 2018) |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Environment Act 2000 (as at 2006) |

| Environment (Prescribed Activities) Regulation 2002 (under Environment Act 2000) |

| Customs (Prohibited Imports) (Plastic Shopping Bags) Regulation 2009 and (Amendment) and 2011 |

| Full ban on importing or manufacturing plastic bags announced in 2018. This followed a ban on importing or manufacturing nonbiodegradable plastic bags that came into effect in 2014. Levies on imports and manufacturing of plastic bags. Ban came into effect 31st January 2020. |

| Environment (Amendment) Act 2014 |

| Local-Level Governments Administration Act 1997 |

| Local-Level Governments Administration Act 1997 Amendment No. 47 (2014) 1997 (amendment No. 47 2014) |

| Organic Law on Provincial and Governments and Local-Level Governments 1998 |

| Public Health Act 1973 (as at 1973) |

| Public Health (Sanitation and General) Regulation 1973 |

| Public Health (Sewerage) Regulation 1973 |

| Public Health (Septic Tanks) Regulation 1973 |

| National Water Supply and Sanitation Act 2016 |

| Marine Pollution (Sea Dumping) Act No. 37 of 2013. (repeals the Dumping of Wastes at Sea Act 1979). |

| Environmental Contaminants Act 1978 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| PNG Development Strategic Plan 2010–2030 (2010) |

| National Health Plan 2011–2020 |

| PNG National Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH Policy) 2015–2030 |

| National Climate Compatible Development Management Policy |

| Papua New Guinea Vision 2050 (2009) |

| National Strategy for Responsible Sustainable Development for Papua New Guinea (2nd Ed, 2014) (StaRS) |

| Medium Development Plan III 2018–2022 |

| National Oceans Policy of Papua New Guinea 2020–2030 |

| National Implementation Plan for Management of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Papua New Guinea (2009) |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Agriculture and Fisheries Ordinance 1959 |

| Pesticides Regulations 2011 |

| Forestry Management Act 2011 |

| Health Ordinance 1959 |

| Land, Surveys and Environment Act 1989 |

| Plastic Bag Prohibition on Importation Regulations 2006 |

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008 |

| National Parks and Reserves Act 1974 |

| Planning and Urban Management Act 2004 |

| Police Offences Ordinance 1961 |

| Quarantine and Biosafety Act 2005 |

| Samoa Water Authority Act 2003 |

| Samoa Water Authority (Sewerage and Wastewater) Regulations 2009 |

| Tourism Development Act 2012 |

| Water Resources Management Act 2008 |

| Waste Management Act 2010 |

| Waste Management (Importation of Waste for Electricity Generation) Regulations 2015 |

| Waste (Plastic Bag) Management Regulations 2018 |

| Waste (Plastic Bag Management Amendment Regulations 2020 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| Apia Waterfront Development Project Waterfront Plan 2017–2026 |

| City Development Strategy 2015 |

| Ministry of Natural Resources & Environment: Corporate Plan 2019–2021 |

| National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2015–2020 |

| National Implementation Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants 2004 |

| National Infrastructure Strategic Plan 2011 |

| National Waste Management Strategy 2019–2023 |

| National Environment Sector Plan (NESP) 2017–2021 |

| National Community Development Sector Plan 2016–2021 |

| Reports |

| National Inventory of E-wastes 2009 |

| Review of Natural Resource and Environment-Related Legislation: Samoa 2018 |

| Samoa Profile in the Solid Waste and Recycling Sector 2018 |

| State of Environment Report 2013 |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Environment Act 1998 |

| Environment Regulations 2008 |

| Environment Regulation (Amendment) Regulation 2014 |

| Environmental Health Act 1980 |

| Environmental Health (Public Health Act) Regulations. (1980) |

| Honiara City Act 1999 |

| Honiara City Council (Litter) Ordinance 2009 |

| Provincial Government Act 1997 |

| Ports Act 1956 |

| Solomon Islands Water Authority Act 1996 |

| Solomon Islands Water Authority (Catchment Areas) Regulations LN 42 1995 |

| Biosecurity Act 2013 |

| Customs and Excise Act 2003 |

| Consumer Protection Act 1995 |

| Fisheries Management Act 2015 |

| Pure Food Act 1996 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| Rural Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene Policy 2014 |

| National Development Strategy 2016–2035 |

| National Implementation Plan for Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018 |

| National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2009–2014 |

| National Waste Management and Pollution Control Strategy 2017–2026 |

| National Climate Change Policy (NCCP) 2012–2017 |

| Solomon Islands National Plan of Action (CTI) |

| The National Biodiversity Action Plan 2016–2020 |

| Reports |

| Baseline Study for the Pacific Hazardous Waste Management Project – Healthcare Waste: Solomon Islands 2014 |

| Eco-Bag Pilot Project Report 2016 |

| Honiara Waste Characterisation Audit Report 2011 |

| PacWaste E-Waste Country Assessments – Solomon Islands Country Report Extract 2014 |

| Public Environment Report (Ranadi Dumpsite Environment Impact Assessment) 2013 |

| Review of Natural Resource and Environment Related Legislation: Solomon Islands (SPREP) 2018 |

| Solid Waste Management in Honiara 2008 |

| Solid Waste Management in the Pacific: Solomon Islands Country Snapshot 2014 |

| Solomon Islands Profile in the Solid Waste and Recycling Sector 2018 |

| SPREP Solid Waste Management Project 2000 |

| Taro Integrated Solid Waste Management Workshop Program Report 2015 |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Waste Management Act 2005 (revised 2016) |

| Waste Management (Plastic Levy) Regulations 2013 |

| Hazardous Wastes and Chemicals Act (revised 2016) |

| Environment Management Act 2010 |

| Environment Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2016 |

| Public Health Act 1992 |

| Public Health (Amendment) Act 2002 |

| Public Health (Amendment) Act 2005 |

| Pesticides Act 2002 |

| Ozone Layer Protection Act |

| Ozone Layer Protection (Amendment) Act 2014 |

| Biosafety Act 2009 |

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2002 |

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act (Amendment) 2009 |

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act (Amendment) 2012 |

| Tonga Tourism Authority Act 2012 |

| Fisheries Management Act 2002 |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| Tonga National Infrastructure Investment Plan (NIIP) (2013–2023) |

| Tonga National Strategic Development Framework 2015–2025 |

| National Waste Management Strategy (Draft) |

| National Implementation Plan (POPS) |

| Reports |

| Tonga Profile in the Solid Waste and Recycling Sector 2018 |

| State of Environment Report 2018 |

| Tonga Review of Natural Resource and Environment Related Legislation 2018 |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Waste Operations and Services Act 2009 |

| Waste Management Act 2017 |

| Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019 |

| Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 |

| Waste Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2018 |

| Environment Protection Act (2008 Revised Edition), Cap 30.25 |

| Environment Protection Act (2008 Revised Edition), Cap 30.25 |

| Environment Protection (Waste Reform) Amendment Act 2017 |

| Environment Protection (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2013 |

| Environnent Protection (Environnemental Impact Assessment) Régulations 2014 |

| Ozone Layer Protection Act (2008) |

| Ozone Depleting Substances (ODS) Regulations 2010 |

| Public Health Act (2008) |

| Public Health Regulations |

| Waste Operations and Services Act 2009 |

| Pesticides Act (2008) |

| Customs Revenue and Border Protection Act 2014 |

| Falekaupule Act/Local Government Act (2008) |

| Penal Code (2008) |

| Criminal Procedure Code (2008) |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| Infrastructure Strategy and Investment Plan 2016–2025 |

| Integrated Waste Policy and Action Plan 2017–2026 |

| National Action Plan to Combat Land Degradation and Drought 2006 |

| National Action Plan to Reduce Releases of Unintentional Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018–2022 |

| National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2012–2016 |

| National Environment Management Strategy 2015–2020 |

| National Implementation Plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants 2008 |

| National Strategic Action Plan for Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management 2012–2016 |

| National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2016–2020 |

| Sustainable and Integrated Water and Sanitation Policy 2012–2021 |

| Reports |

| Review of Natural Resource and Environment-Related Legislation: Tuvalu 2018 |

| PacWaste Plus Legislative Review (University of Melbourne) |

| 3R Progress Country Report (Draft) |

| National Report to the Third International Conference on Small Island Developing States 2014 |

| Profile in the Solid Waste and Recycling Sector: Tuvalu 2018 |

| Second National Communication to the UNFCCC 2015 |

| Solid Waste Management in the Pacific: Tuvalu Country Snapshot 2014 |

| Waste Policy Performance Review 2019 |

| Legislation & Regulations |

| Waste Management Act 2014 |

| Waste Management Regulations Order No 15 of 2018 |

| Private Waste Operator’s Licence Fees Order No 16 of 2018 |

| Waste Management Penalty Notice Regulation Order No 17 of 2018 |

| Pollution Control Act 2013 |

| Environment and Conservation Act 2002 |

| Environment and Conservation Amendment Act 2010 |

| Water Resources Management Act 2002 (as at 2006) |

| Water Resources Management (Amendment) Act 2016 |

| Public Health Act 1994 |

| Public Health (Amendment) Act 2018 |

| Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010 |

| Ozone Layer Protection Act No. 27 of 2010 |

| Ozone Layer Protection (Amendment) Act No. 4 of 2014 |

| Schedule to the Ozone Layer Protection Act No. 27 of 2010 (Amendment) Order |

| National Policies, Plans and Strategies |

| National Waste Management and Pollution Control Strategy and Implementation Plan 2016–2020 |

| Vanuatu National Water Strategy 2018–2030 |

| National Sustainable Development Plan 2016–2030 |

| National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2018–2030 |

Appendix B

- Duke University Plastics Policy Inventory

- FAOLEX

- ECOLEX

- The Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute (PacLII)

- Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility (2018) Pacific Region Solid Waste Management and Recycling Country and Territory Profiles. Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility (PRIF). Sydney, Australia.

- Peel, J., L. Godden, A. Palmer, R. Gardner, and R. Markey-Towler (2020). Stocktake of Existing and Pipeline Legislation in the 15 PacWastePlus Participating Countries. University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

- Raubenheimer, Karen (2019). Desktop studies on principles of waste management and funding mechanisms in relation to the Commonwealth Litter Programme (CLiP): Vanuatu and Solomon Islands. University of Wollongong Australia, Wollongong, Australia.

- National official online sources of legislation. For example, the Laws of Fiji.

- InforMEA

- Karasik, R., T. Vegh, Z. Diana, J. Bering, J. Caldas, A. Pickle, D. Rittschof, and J. Virdin. 2020. 20 Years of Government Responses to the Global Plastic Pollution Problem: The Plastics Policy Inventory. NI X 20-05. Durham, NC: Duke University.

- Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA). (April 2020). Islands of Opportunity: Toward a Global Agreement on Plastic Pollution for Pacific Island Countries and Territories. London, UK: EIA.

- Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) (June 2020). Convention on Plastic Pollution: Toward a new global agreement to address plastic pollution. London, UK: EIA.

- SPREP (2019). PACPOL Strategy and Workplan prepared by Asia-Pacific ASA (APASA) for the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment. Apia, Samoa: SPREP.

- SPREP (2016). Cleaner Pacific 2025: Pacific Regional Waste and Pollution Management Strategy 2016–2025. Apia, Samoa: SPREP.

- Commonwealth Marine Economies Programme (2018). Pacific Marine Climate Change Report Card.

References

- Piccardo, M.; Provenza, F.; Grazioli, E.; Cavallo, A.; Terlizzi, A.; Renzi, M. PET microplastics toxicity on marine key species is influenced by pH, particle size and food variations. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsaheb, M.; Hossini, H.; Makhdoumi, P. Review of microplastic occurrence and toxicological effects in marine environment: Experimental evidence of inflammation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 142, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steer, M.; Thompson, R.C. Plastics and Microplastics: Impacts in the Marine Environment. In Mare Plasticum-The Plastic Sea; Streit-Bianchi, M., Cimadevila, M., Trettnak, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelle, S.B.; Ringma, J.; Law, K.L.; Monnahan, C.C.; Lebreton, L.; McGivern, A.; Murphy, E.; Jambeck, J.R.; Leonard, G.; Hilleary, M.A.; et al. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, S.; Ferrón, S.; Wilson, S.T.; Karl, D.M. Production of methane and ethylene from plastic in the environment. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, M.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y. (Micro) plastic crisis: Un-ignorable contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Ye, S.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, L.; Tang, W.; Wen, X.; Liu, S. Can microplastics pose a threat to ocean carbon sequestration? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations “The Future We Want”: Outcome Document of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio de Janeiro; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Making Development Co-Operation Work for Small Island Developing States; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme Oceans and Small Island States: First Think Opportunity, Then Think Blue. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2017/2/22/Oceans-and-small-island-states-First-think-opportunity-then-think-blue.html (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Andrew, N.L.; Bright, P.; de la Rua, L.; Teoh, S.J.; Vickers, M. Coastal proximity of populations in 22 Pacific Island Countries and Territories. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Haynes, D.; Talouli, A.; Donoghue, M. Marine pollution originating from purse seine and longline fishing vessel operations in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, 2003–2015. Ambio 2017, 46, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R.V. Evaluating Environmental Policy Success and Failure. In Environmental Policy in the 1990s: Towards a New Agenda, 2nd ed.; Vig, N., Kraft, M., Eds.; Congressional Quarterly Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 167–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, P.G.; Schofield, A. Low densities of macroplastic debris in the Pitcairn Islands Marine Reserve. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, F.; Almroth, B.C.; Baumann, H.; Broström, G.; Corvellec, H.; Gipperth, L.; Hasselov, M.; Karlsson, T.; Nilsson, P. Marine plastic litter on small island developing states (SIDS): Impacts and measures. Swed. Instit. Mar. Environ. 2017, 4, 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Plastic Free—Pollution Free Fiji Campaign. Available online: https://oceanconference.un.org/commitments/?id=21080 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. Pacific Regional Action Plan: Marine Litter 2018–2025; SPREP: Apia, Samoa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Raubenheimer, K.; Oral, N.; McIlgorm, A. Combating Marine Plastic Litter and Microplastics: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Relevant International, Regional and Sub regional Governance Strategies and Approaches; United Nations Environment: Nairobi, Kenya, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelle, S.; Rochman, C.; Liboiron, M.; Bond, A.; Lusher, A.; Bradshaw, H.; Provencher, J. Opinion: Why we need an international agreement on marine plastic pollution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9994–9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Investigation Agency. Convention on Plastic Pollution: Toward a New Global Agreement to Address Plastic Pollution; EIA: London, UK, June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly, T.; Failler, P. Governing plastic pollution in the oceans: Institutional challenges and areas for action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, M.; Di Biccari, C.; Lazoi, M.; Corallo, A. A gap analysis methodology for product lifecycle management assessment. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2017, 65, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, K. Desktop Studies on Principles of Waste Management and Funding Mechanisms in Relation to the Commonwealth Litter Programme (CLiP): Vanuatu and Solomon Islands; University of Wollongong: Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.J. Benchmarking: A process for learning or simply raising the bar? Eval. J. Australas. 2009, 92, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Weinfurter, A.J.; Xu, K. Aligning subnational climate actions for the new post-Paris climate regime. Clim. Chang. 2017, 142, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. The regime complex for climate change. Perspect. Politics 2011, 9, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O. Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, K.W.; Genschel, P.; Snidal, D.; Zangl, B. International Organizations as Orchestrators; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Asselt, H.; Zelli, F. Connect the dots: Managing the fragmentation of global climate governance. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2014, 16, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Savino, I.; Locaputo, V.; Uricchio, V.F. Detailed review study on potential effects of microplastics and additives of concern on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-la-Torre, G.E. Microplastics: An emerging threat to food security and human health. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in seafood and the implications for human health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassotis, C.D.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Demeneix, B.A.; Porta, M.; Slama, R.; Trasande, L. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: Economic, regulatory, and policy implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muncke, J.; Andersson, A.M.; Backhaus, T.; Boucher, J.M.; Almroth, B.C.; Castillo, A.C.; Chevrier, J.; Demeneix, B.A.; Emmanuel, J.A.; Fini, J.-B.; et al. Impacts of food contact chemicals on human health: A consensus statement. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacific Region Infrastructure Facility. Pacific Region Solid Waste Management and Recycling—Pacific Country and Territory Profiles; PRIF: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey, L. Challenges to Plastic Up-Cycling in Small Island Communities: A Palauan Tale; Scripps Institute of Oceanography and Centre for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation: Sand Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, M.; Carvan, A.; Williams, S. Mid-Term Evaluation of the Kiribati Solid Waste Management Programme; New Zealand Foreign Affairs and Trade Aid Programme: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Japan International Cooperation Agency Data Collection Surveys on Reverse Logistics in the Pacific Islands; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2013.

- Sommer, F.; Dietze, V.; Baum, A.; Sauer, J.; Gilge, S.; Maschowski, C.; Gieré, R. Tire abrasion as a major source of microplastics in the environment. Aerosol. Air Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 2014–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 112, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP/EA.2/Res. 11 Marine Plastic Litter and Microplastics; United Nations Environmental Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- SCS Engineers Prefeasibility Study: Waste-to-Energy Facility, Majuro, the Republic of the Marshall Islands; Asian Development Bank: Marjuro, Marshall Islands, 2010.

- Nielsen, T.D.; Hasselbalch, J.; Holmberg, K.; Stripple, J. Politics and the plastic crisis: A review throughout the plastic life cycle. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2020, 9, e360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme. Cleaner Pacific 2025, Pacific Regional Waste and Pollution Management Strategy 2016–2025; SPREP: Apia, Samoa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Northcott, G.; Pantos, O. Biodegradable and Environmental Impact of Oxo-Degradable and Polyhydroxylkanoate and Polylactic Acid Biodegradable Plastics; Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, L.; Dierkes, G.; Ternes, T.A.; Völker, C.; Wagner, M. Benchmarking the in vitro toxicity and chemical composition of plastic consumer products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11467–11477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Biodegradable and Compostable Plastics in the Environment; PCE: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, N.; Knoblauch, D.; Mederake, L.; McGlade, K.; Schulte, M.L.; Masali, S. No More Plastics in the Ocean. Gaps in Global Plastic Governance and Options for a Legally Binding Agreement to Eliminate Marine Plastic Pollution. Draft Report for WWF to Support Discussions at the Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group on Marine Litter and Microplastics; Adelphi: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. Rethinking Plastics in Aotearoa New Zealand; NZPMCSA: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.M. A Zero Waste Hierarchy for Europe. New Tools for New Times: From Waste Management to Resource Management; Zero Waste Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/2019/05/a-zero-waste-hierarchy-for-europe/ (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Zero Waste Europe. Seizing the Opportunity: Using Plastic Only Where It Makes Sense. Available online: https://rethinkplasticalliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ZWE-Position-paper-Plastics-reduction-targets.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Ling, J. Maori Weavers Call for Kete to Replace Plastic Bags. Stuff. 8 August 2018. Available online: https://www.stuff.co.nz/auckland/local-news/northland/106068446/maori-weavers-call-for-kete-to-replace-plastic-bags (accessed on 3 January 2020).

| Category | Themes | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Global objectives | Long-term Elimination of Discharges | Sustainable, Long-term Solutions. |

| Safe circular economy for plastics | A circular economy has minimal waste and reuses raw materials again and again. Any materials circulating in the economy are safe by design, allowing their introduction into the economy and their reuse without risks for human health and the environment. This includes keeping ‘substances of very high concern’ (e.g., POPs as plastic additives) out of the circular economy and ultimately aims to eliminate them entirely. | |

| Intergenerational equity and justice | Ensures future generations flourish as a result of the current policy, legislation and action. | |

| SDGs | Progresses the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Target 3: Good health and well-being Target 6: Clean water and sanitation Target 11: Sustainable cities and communities Target 12: Responsible consumption and production Target 13: Climate action Target 14: Life below water (protection of the seas and oceans) Target 15: Life on land (restore ecosystems and preserve diversity). | |

| Protection of human health | The connection between plastics and human health is explicit and/or provisions made. | |

| Vertical integration | Responds to regional and international obligations. | |

| Horizontal Integration | Evidence of coherence between legislation, and national policies, plans and strategies (inter-ministerial cooperation). | |

| Precautionary approach | Lack of scientific data or certainty is not a reason for not acting to prevent serious or irreversible damage. | |

| Waste hierarchy | There is either explicit reference to the waste hierarchy and/or a focus on the top of the waste hierarchy (refuse, reduce, reuse, redesign). | |

| Climate Change | The connection between plastic pollution and climate change is made explicit and/or provisions are made. | |

| Waste prevention | Trade in non-hazardous, recyclable and reusable plastics | Import and export bans and restrictions, minimum environmental standards for plastics imports and exports, fees on problematic imported plastic. |

| Sustainable financing mechanisms/market-based instruments | Examples include waste-management fees, deposit-refund schemes, extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes, licensing schemes, plastic taxes and levies, advanced disposal fees, polluter pays, and user pays. | |

| Government infrastructure investments | The government invests in accessible and regular separate waste collection, recycling, reuse, and preventative measures. | |

| Recognised impact on economic development | An explicit link is made between the impact of plastic pollution on economic development (e.g., tourism, safe and secure employment opportunities, agriculture). This might also factor in the economic cost of not preventing plastic pollution/inaction. Plastic pollution is presented as a potential business risk. | |

| National reduction targets | Measurable plastic pollution reduction targets and timelines. | |

| Virgin plastic use | Controls and standards to reduce virgin plastics entering the economy (e.g., caps). | |

| Market Restrictions | Prohibitions on certain polymers and additives and controls on the use of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs), Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), and carcinogens. | |

| Promotion of traditional/local solutions | E.g., woven reusable bags to replace single-use plastic bags, leaf wraps for food, and the promotion of traditional/local knowledge. | |

| Waste management | Closed-loop recycling (primary market) or secondary markets | Secondary (‘cascade’ markets) recycling is also known as ‘downcycling’ from a higher value product to a lower grade product, e.g., from a PET bottle into a less/non- recyclable product such as carpet. |

| Remediation and legacy pollution | Includes protocols and guidelines to recover legacy plastics (e.g., marine debris) to be safely reused, recycled or repurposed and remediation of landfills (e.g., following storm damage). | |

| Transport | Transport infrastructure; access; port capacity; backloading (filling empty trucks and/or shipping containers with waste on their return to point of origin/producers); and reverse logistics (shipping the product back to the producer post-consumption for recycling or reuse). | |

| Microplastics | Intentionally added (e.g., microbeads) | Restrictions on the importation and trade of products with added microbeads. |

| Wear and tear (e.g., tyres, textiles) | Restrictions on the importation of plastic products with high wear and tear. | |

| Agriplastics | Management and prevention of plastics used in agriculture such as plastic mulch and microbeads in controlled-release fertilizers. | |

| Management (e.g., pellets) | Handling guidelines or restrictions. | |

| Standardisation | Product design | Eco- and bio- benign product design. |

| Polymer restrictions | Restrictions on the importation and trade of certain polymers. | |

| Additive restrictions | Restrictions on the importation and use of toxic additives and monomers, such as those categorised as EDCs, POPs, and carcinogens. | |

| Voluntary certification schemes and industry standards | Compliance to certification schemes such as ISO for home compost-ability; and products and services certified ‘zero waste to landfill’. Businesses commit to reducing plastics throughout their supply chain. | |

| Mandatory product stewardship | Government mandated participation in accredited schemes for the stewardship of plastic products. | |

| National monitoring and reporting, national inventories and reduction targets | Tracking of production, trade, consumption, and recycled content, final treatment. National reduction targets with agreed timelines. | |

| Transparency and Freedom of information (consumer justice, labelling) | Information is readily available to the consumer. Information could include recycled content, recyclability, appropriate disposal, compost-ability, additives, GHGs, and hazard potential. | |

| Compliance measures (monitoring and reporting) and enforcement | Minimum requirements, monitoring and reporting. Mechanisms for managing suspected or identified instances of non-compliance such as financial penalties, imprisonment, or confiscation. | |

| Definitions | Standardised definitions, e.g., ‘reusable’, ‘compostable’, ‘recyclable’, ‘biodegradable’. |

| Legislation | Long-term Elimination of Discharges | Safe Circular Economy for Plastics | Intergenerational Equity and Justice | SDGs | Protection of Human Health | Vertical Integration | Horizontal Integration | Precautionary Approach | Waste Hierarchy | Climate Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji | Environment Management Act 2005 Amendments and Regulations 24 June 2019 | ||||||||||

| Litter Act 2008 and Litter (Amendment) Act (2010) | |||||||||||

| Public Health Act 1935 including Public Health Regulations 1937 (as at 1 August 2018) [PHA 128]; and Public Health and Sanitary Services Regulations 1941 | |||||||||||

| Climate Change Bill 2019 | |||||||||||

| Republic of Fiji Climate Change Policy 2012 | |||||||||||

| Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011–2014 | |||||||||||

| Kiribati | Environment (Amendment) Act 2007 | ||||||||||

| Special Fund (Waste Materials Recovery) Act 2004 | |||||||||||

| Kiribati Solid Waste Management Plan (KSWMP) | |||||||||||

| Kiribati 20-year Vision 2016–2036 or KV20 | |||||||||||

| Kiribati Development Plan 2016–2019 | |||||||||||

| Marshall Islands | Styrofoam cups and plates, and plastic products prohibition, and container deposit Act 2016 | ||||||||||

| Styrofoam Cups and Plates, and Plastic Products Prohibition Container Deposit (Amendment) Act, 2018 (2018-0054) | |||||||||||

| National Environment Management Strategy 2017–2022 | |||||||||||

| Kwajalein Atoll Local Government Solid Waste Management Plan 2019–2028 | |||||||||||

| Palau | National Code: Title 24: Environmental Protection | ||||||||||

| The Recycling Act 2006 (including 2009 Amendments) | |||||||||||

| Plastic Bag Use Reduction Act 2017 | |||||||||||

| Zero Disposable Plastic Policy, Executive Order No. 417 | |||||||||||

| The National Solid Waste Management Strategy: the roadmap towards a clean and safe Palau 2017–2026 | |||||||||||

| Papua New Guinea | Environmental Contaminants Act 1978 | ||||||||||

| Environment Act 2000 | |||||||||||

| Public Health Act 1973 | |||||||||||

| STaR | |||||||||||

| Samoa | Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008 | ||||||||||

| Samoa Water Authority Act 2003—Samoa Water Authority (Sewerage and Wastewater) Regulations 2009 | |||||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2010 | |||||||||||

| Waste (Plastic Bag) Management Regulations 2018 | |||||||||||

| National Waste Management Strategy 2019–2023 | |||||||||||

| Solomon Islands | National WMAP Strategy | ||||||||||

| The Environmental Health (Public Health Act) Regulations 1980 | |||||||||||

| Environment Act 1998 | |||||||||||

| Shipping (Marine Pollution) Regulation | |||||||||||

| Tonga | Waste Management (Plastic Levy) Regulations 2013 | ||||||||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | |||||||||||

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act | |||||||||||

| Hazardous Wastes and Chemicals Act 2010 | |||||||||||

| Tuvalu | Ozone Layer Protection Act | ||||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2017 | |||||||||||

| Waste Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2018 | |||||||||||

| Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019 | |||||||||||

| Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 | |||||||||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | |||||||||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act (2008) | |||||||||||

| Integrated Waste Policy and Action Plan 2017–2026 | |||||||||||

| Vanuatu | National Action Plan to Reduce Releases of Unintentional Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018–2022 | ||||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2014 | |||||||||||

| Regulations 2018 | |||||||||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010 |

| International Agreements | Description | Fiji | Kiribati | Marshall Islands | Palau | Papua New Guinea | Samoa | Solomon Islands | Tonga | Tuvalu | Vanuatu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNCLOS—United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982) | Legally binding global instrument for the protection of the marine environment from all sources of pollution. | ||||||||||

| MARPOL 73/78 Annex V | Legally binding global instrument to prevent marine pollution from ships (Annex V—Prevention of pollution by garbage from ships (includes all plastics and fishing gear) | ||||||||||

| London Convention 72 (“Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and other Matter”) | Legally binding global instrument listing prohibited pollutants and those requiring permits for dumping (intentional dumping into the sea) | ||||||||||

| London Convention Protocol 96 | Legally binding agreement for the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (1996) | ||||||||||

| Conservation Management Measure on Marine Pollution (2019) | Prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds to Support the Implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14, International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) Annex V, London Convention and London Protocol. | ||||||||||

| Intervention Protocol 73 | Concerning pollutants other than oil in the high seas. | ||||||||||

| Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) | The CBD has three main objectives: (1) The conservation of biological diversity, (2) The sustainable use of the components of biological diversity, (3) The fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources. | ||||||||||

| The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SDGs) | Broad scope including pollution management. | ||||||||||

| Basel Convention 1992 (Plastic Waste Amendments) | Legally binding global instrument on the transboundary movement of hazardous wastes and other wastes (plastics as other wastes). | ||||||||||

| Stockholm Convention (2004) | Legally binding global instrument to control persistent organic pollutants. | ||||||||||

| Rotterdam Convention (2004) | The Convention creates legally binding obligations for the implementation of prior informed consent in the trade of hazardous waste.2019 decisions to protect human health and the environment from the harmful effects of chemicals and wastes, including plastic waste. | ||||||||||

| International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM) 2004 | Adopted in 2004. Aims to prevent the spread of harmful aquatic organisms from one region to another by establishing standards and procedures for the management and control of ships’ ballast water and sediments. | ||||||||||

| Nairobi WRC (2007) | A legal basis for coastal states to remove wrecks which pose a hazard to the safety of navigation or to the marine and coastal environments. Covers prevention, mitigation or elimination of hazards created by any object lost at sea from a ship (e.g., lost containers). | ||||||||||

| Hong Kong Convention (2009) | Aimed at ensuring that ships do not pose any unnecessary risk to human health and safety or to the environment when recycled after reaching the end of their operational lives. | ||||||||||

| United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (1992) | Climate change convention 1993 | ||||||||||

| Montreal Protocol (1987) | Designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances responsible for ozone depletion. | ||||||||||

| Vienna Convention on the Protection of the Ozone Layer | |||||||||||

| Strategies | |||||||||||

| The Honolulu Strategy (2011) | A global framework for prevention and management of marine debris including land and sea-based sources |

| Policy Instrument or Strategy | Description | Fiji | Kiribati | Marshall Islands | Palau | Papua New Guinea | Samoa | Solomon Islands | Tonga | Tuvalu | Vanuatu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noumea Convention (1990) | Legally binding regional agreement to prevent marine Pollution from ships in the South Pacific. | ||||||||||

| Protocol for the Prevention of Pollution of the South Pacific Region by Dumping (1986) | “SPREP Dumping Protocol”—prohibits the dumping of wastes from ships. | ||||||||||

| Noumea Protocol on Combatting Pollution Emergencies (1990) | In the event of a pollution emergency, prompt and effective action should be taken initially at the national level to organise and co-ordinate prevention, mitigation and clean-up activities. | ||||||||||

| Waigani Convention (2001) | Supports the regional implementation of the international hazardous waste control regime (Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions), and the London Convention. | ||||||||||

| The SAMOA Pathway (2014) | Supporting and implementing existing instruments aimed at sustainable development in the Pacific region. | ||||||||||

| Framework for Pacific Regionalism (2014) | Sustainable development that combines economic, social and cultural development in ways that improve livelihoods and well-being and use the environment sustainably. Regional policies complement national efforts. | ||||||||||

| Pacific Ocean Pollution Prevention Programme (PACPOL) 2015–2020 | Sets out 15 work plans to “promote safe, environmentally sound, efficient, and sustainable shipping” throughout the Pacific region. | ||||||||||

| Pacific Regional Waste and Pollution Management Strategy 2016–2025 (Cleaner Pacific 2025) | A regional framework for sustainable waste management and pollution prevention in the Pacific region up until 2025. | ||||||||||

| SPREP Strategic Plan 2017–2026 | Prioritises four regional goals with supporting objectives. Together these define the core priorities and focus of SPREP for the next ten years. | ||||||||||

| Pacific Marine Litter Action Plan 2018–2025 (MLAP) | Aimed to address the plastic pollution crisis and sets out the key actions to minimise marine pollution across PICTs under the auspices of the Noumea Convention and the Cleaner Pacific 2025 Strategy. |

| Country | Legislation | Trade in Non-hazardous, Recyclable and Reusable Plastics | Legal Basis for Sustainable Financing Mechanisms | Infrastructure Investments | Economic Development/ Legal Basis for Loss or Damage | National Reduction Targets | Virgin Plastic Use | Market Restrictions | Promotion of Traditional Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji | Environment Management Act 2005 / Amendments and Regulations 24 June 2019 | ||||||||

| Litter Act 2008 and Litter (Amendment) Act (2010) | |||||||||

| Public Health Act 1935 including Public Health Regulations 1937 (as at 1 August 2018) [PHA 128]; and Public Health and Sanitary Services Regulations 1941 | |||||||||

| Climate Change Bill 2019 | |||||||||

| Republic of Fiji Climate Change Policy 2012 | |||||||||

| Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011–2014 | |||||||||

| Kiribati | Environment (Amendment) Act 2007 | ||||||||

| Special Fund (Waste Materials Recovery) Act 2004 | |||||||||

| Kiribati Solid Waste Management Plan (KSWMP) | |||||||||

| Kiribati 20-year Vision 2016-2036 or KV20 | |||||||||

| Kiribati Development Plan 2016–2019 | |||||||||

| Marshall Islands | Styrofoam cups and plates, and plastic products prohibition, and container deposit Act 2016 | ||||||||

| Styrofoam Cups and Plates, and Plastic Products Prohibition Container Deposit (Amendment) Act, 2018 (2018-0054) | |||||||||

| National Environment Management Strategy 2017–2022 | |||||||||

| Kwajalein Atoll Local Government Solid Waste Management Plan 2019–2028 | |||||||||

| Palau | National Code: Title 24: Environmental Protection | ||||||||

| The Recycling Act 2006 (including 2009 Amendments) | |||||||||

| Plastic Bag Use Reduction Act 2017 | |||||||||

| Zero Disposable Plastic Policy, Executive Order No. 417 | |||||||||

| The National Solid Waste Management Strategy: the roadmap towards a clean and safe Palau 2017–2026 | |||||||||

| Papua New Guinea | Environmental Contaminants Act 1978 | ||||||||

| Environment Act 2000 | |||||||||

| Public Health Act 1973 | |||||||||

| STaR | |||||||||

| Samoa | Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008 | ||||||||

| Samoa Water Authority Act 2003—Samoa Water Authority (Sewerage and Wastewater) Regulations 2009 | |||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2010 | |||||||||

| Waste (Plastic Bag) Management Regulations 2018 | |||||||||

| National Waste Management Strategy 2019–2023 | |||||||||

| Solomon Islands | National WMAP Strategy | ||||||||

| The Environmental Health (Public Health Act) Regulations 1980 | |||||||||

| Environment Act 1998 | |||||||||

| Shipping (Marine Pollution) Regulation | |||||||||

| Tonga | Waste Management (Plastic Levy) Regulations 2013 | ||||||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | |||||||||

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act | |||||||||

| Hazardous Wastes and Chemicals Act 2010 | |||||||||

| Tuvalu | Ozone Layer Protection Act | ||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2017 | |||||||||

| Waste Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2018 | |||||||||

| Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019 | |||||||||

| Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 | |||||||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | |||||||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act (2008) | |||||||||

| Integrated Waste Policy and Action Plan 2017–2026 | |||||||||

| Vanuatu | National Action Plan to Reduce Releases of Unintentional Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018–2022 | ||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2014 | |||||||||

| Regulations 2018 | |||||||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010 |

| Country | Legislation, Policies and Plans | Closed-Loop Recycling (Primary Market) or Secondary Markets | Remediation and Legacy Pollution | Transport |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji | Environment Management Act 2005/Amendments and Regulations 24 June 2019 | |||

| Litter Act 2008 and Litter (Amendment) Act (2010) | ||||

| Public Health Act 1935 including Public Health Regulations 1937 (as at 1 August 2018) [PHA 128]; and Public Health and Sanitary Services Regulations 1941 | ||||

| Climate Change Bill 2019 | ||||

| Republic of Fiji Climate Change Policy 2012 | ||||

| Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011–2014 | ||||

| Kiribati | Environment (Amendment) Act 2007 | |||

| Special Fund (Waste Materials Recovery) Act 2004 | ||||

| Kiribati Solid Waste Management Plan (KSWMP) | ||||

| Kiribati 20-year Vision 2016–2036 or KV20 | ||||

| Kiribati Development Plan 2016–2019 | ||||

| Marshall Islands | Styrofoam cups and plates, and plastic products prohibition, and container deposit Act 2016 | |||

| Styrofoam Cups and Plates, and Plastic Products Prohibition Container Deposit (Amendment) Act, 2018 (2018-0054) | ||||

| National Environment Management Strategy 2017–2022 | ||||

| Kwajalein Atoll Local Government Solid Waste Management Plan 2019–2028 | ||||

| Palau | National Code: Title 24: Environmental Protection | |||

| The Recycling Act 2006 (including 2009 Amendments) | ||||

| Plastic Bag Use Reduction Act 2017 | ||||

| Zero Disposable Plastic Policy, Executive Order No. 417 | ||||

| The National Solid Waste Management Strategy: the roadmap towards a clean and safe Palau 2017–2026 | ||||

| Papua New Guinea | Environmental Contaminants Act 1978 | |||

| Environment Act 2000 | ||||

| Public Health Act 1973 | ||||

| STaR | ||||

| Samoa | Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008 | |||

| Samoa Water Authority Act 2003—Samoa Water Authority (Sewerage and Wastewater) Regulations 2009 | ||||

| Waste Management Act 2010 | ||||

| Waste (Plastic Bag) Management Regulations 2018 | ||||

| National Waste Management Strategy 2019–2023 | ||||

| Solomon Islands | National WMAP Strategy | |||

| The Environmental Health (Public Health Act) Regulations 1980 | ||||

| Environment Act 1998 | ||||

| Shipping (Marine Pollution) Regulation | ||||

| Tonga | Waste Management (Plastic Levy) Regulations 2013 | |||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | ||||

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act | ||||

| Hazardous Wastes and Chemicals Act 2010 | ||||

| Tuvalu | Ozone Layer Protection Act | |||

| Waste Management Act 2017 | ||||

| Waste Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2018 | ||||

| Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019 | ||||

| Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 | ||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | ||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act (2008) | ||||

| Integrated Waste Policy and Action Plan 2017–2026 | ||||

| Vanuatu | National Action Plan to Reduce Releases of Unintentional Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018–2022 | |||

| Waste Management Act 2014 | ||||

| Regulations 2018 | ||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010 |

| Country | Legislation | Intentionally Added (e.g., Microbeads) | Wear and Tear (e.g., Tyres, Textiles) | Agriplastics | Management (e.g., Pellets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji | Environment Management Act 2005/Amendments and Regulations 24 June 2019 | ||||

| Litter Act 2008 and Litter (Amendment) Act (2010) | |||||

| Public Health Act 1935 including Public Health Regulations 1937 (as at 1 August 2018) [PHA 128]; and Public Health and Sanitary Services Regulations 1941 | |||||

| Climate Change Bill 2019 | |||||

| Republic of Fiji Climate Change Policy 2012 | |||||

| Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011–2014 | |||||

| Kiribati | Environment (Amendment) Act 2007 | ||||

| Special Fund (Waste Materials Recovery) Act 2004 | |||||

| Kiribati Solid Waste Management Plan (KSWMP) | |||||

| Kiribati 20-year Vision 2016–2036 or KV20 | |||||

| Kiribati Development Plan 2016–2019 | |||||

| Marshall Islands | Styrofoam cups and plates, and plastic products prohibition, and container deposit Act 2016 | ||||

| Styrofoam Cups and Plates, and Plastic Products Prohibition Container Deposit (Amendment) Act, 2018 (2018-0054) | |||||

| National Environment Management Strategy 2017–2022 | |||||

| Kwajalein Atoll Local Government Solid Waste Management Plan 2019–2028 | |||||

| Palau | National Code: Title 24: Environmental Protection | ||||

| The Recycling Act 2006 (including 2009 Amendments) | |||||

| Plastic Bag Use Reduction Act 2017 | |||||

| Zero Disposable Plastic Policy, Executive Order No. 417 | |||||

| The National Solid Waste Management Strategy: the roadmap towards a clean and safe Palau 2017–2026 | |||||

| Papua New Guinea | Environmental Contaminants Act 1978 | ||||

| Environment Act 2000 | |||||

| Public Health Act 1973 | |||||

| STaR | |||||

| Samoa | Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008 | ||||

| Samoa Water Authority Act 2003—Samoa Water Authority (Sewerage and Wastewater) Regulations 2009 | |||||

| Waste Management Act 2010 | |||||

| Waste (Plastic Bag) Management Regulations 2018 | |||||

| National Waste Management Strategy 2019–2023 | |||||

| Solomon Islands | National WMAP Strategy | ||||

| The Environmental Health (Public Health Act) Regulations 1980 | |||||

| Environment Act 1998 | |||||

| Shipping (Marine Pollution) Regulation | |||||

| Tonga | Waste Management (Plastic Levy) Regulations 2013 | ||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | |||||

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act | |||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act | |||||

| Tuvalu | Waste Management Act 2017 | ||||

| Waste Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2018 | |||||

| Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019 | |||||

| Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 | |||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | |||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act (2008) | |||||

| Integrated Waste Policy and Action Plan 2017 -2026 | |||||

| National Action Plan to Reduce Releases of Unintentional Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018–2022 | |||||

| Vanuatu | Waste Management Act 2014 | ||||

| Regulations 2018 | |||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010 | |||||

| National Waste Management and Pollution Control Strategy and Implementation Plan 2016–2020 |

| Country | Legislation, Policies and Plans | Product Design | Polymer Restrictions | Additive Restrictions | Voluntary Certification and Industry Standards | Mandatory Product Stewardship | National Monitoring, Reporting and Inventories | Transparency and Freedom of Information | Enforcement | Definitions (Standardisation of) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiji | Environment Management Act 2005/Amendments and Regulations 24 June 2019 | |||||||||

| Litter Act 2008 and Litter (Amendment) Act (2010) | ||||||||||

| Public Health Act 1935 including Public Health Regulations 1937 (as at 1 August 2018) [PHA 128]; and Public Health and Sanitary Services Regulations 1941 | ||||||||||

| Climate Change Bill 2019 | ||||||||||

| Republic of Fiji Climate Change Policy 2012 | ||||||||||

| Fiji National Solid Waste Management Strategy 2011–2014 | ||||||||||

| Kiribati | Environment (Amendment) Act 2007 | |||||||||

| Special Fund (Waste Materials Recovery) Act 2004 | ||||||||||

| Kiribati Solid Waste Management Plan (KSWMP) | ||||||||||

| Kiribati 20-year Vision 2016–2036 or KV20 | ||||||||||

| Kiribati Development Plan 2016–2019 | ||||||||||

| Marshall Islands | Styrofoam cups and plates, and plastic products prohibition, and container deposit Act 2016 | |||||||||

| Styrofoam Cups and Plates, and Plastic Products Prohibition Container Deposit (Amendment) Act, 2018 (2018-0054) | ||||||||||

| National Environment Management Strategy 2017–2022 | ||||||||||

| Kwajalein Atoll Local Government Solid Waste Management Plan 2019–2028 | ||||||||||

| Palau | National Code: Title 24: Environmental Protection | |||||||||

| The Recycling Act 2006 (including 2009 Amendments) | ||||||||||

| Plastic Bag Use Reduction Act 2017 | ||||||||||

| Zero Disposable Plastic Policy, Executive Order No. 417 | ||||||||||

| The National Solid Waste Management Strategy: the roadmap towards a clean and safe Palau 2017–2026 | ||||||||||

| Papua New Guinea | Environmental Contaminants Act 1978 | |||||||||

| Environment Act 2000 | ||||||||||

| Public Health Act 1973 | ||||||||||

| STaR | ||||||||||

| Samoa | Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008 | |||||||||

| Samoa Water Authority Act 2003—Samoa Water Authority (Sewerage and Wastewater) Regulations 2009 | ||||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2010 | ||||||||||

| Waste (Plastic Bag) Management Regulations 2018 | ||||||||||

| National Waste Management Strategy 2019–2023 | ||||||||||

| Solomon Islands | National WMAP Strategy | |||||||||

| The Environmental Health (Public Health Act) Regulations 1980 | ||||||||||

| Environment Act 1998 | ||||||||||

| Shipping (Marine Pollution) Regulation | ||||||||||

| Tonga | Waste Management (Plastic Levy) Regulations 2013 | |||||||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)–Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | ||||||||||

| Marine Pollution Prevention Act | ||||||||||

| Hazardous Wastes and Chemicals Act 2010 | ||||||||||

| Tuvalu | Ozone Layer Protection Act | |||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2017 | ||||||||||

| Waste Management (Litter and Waste Control) Regulations 2018 | ||||||||||

| Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019 | ||||||||||

| Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 | ||||||||||

| Environment Protection Act (2008)—Litter and Waste Control Regulations 2013 | ||||||||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act (2008) | ||||||||||

| Integrated Waste Policy and Action Plan 2017–2026 | ||||||||||

| Vanuatu | National Action Plan to Reduce Releases of Unintentional Persistent Organic Pollutants 2018–2022 | |||||||||

| Waste Management Act 2014 | ||||||||||

| Regulations 2018 | ||||||||||

| Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farrelly, T.A.; Borrelle, S.B.; Fuller, S. The Strengths and Weaknesses of Pacific Islands Plastic Pollution Policy Frameworks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031252

Farrelly TA, Borrelle SB, Fuller S. The Strengths and Weaknesses of Pacific Islands Plastic Pollution Policy Frameworks. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031252

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarrelly, Trisia A., Stephanie B. Borrelle, and Sascha Fuller. 2021. "The Strengths and Weaknesses of Pacific Islands Plastic Pollution Policy Frameworks" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031252

APA StyleFarrelly, T. A., Borrelle, S. B., & Fuller, S. (2021). The Strengths and Weaknesses of Pacific Islands Plastic Pollution Policy Frameworks. Sustainability, 13(3), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031252