A Comparison of the Role of Voluntary Organizations in Disaster Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Design

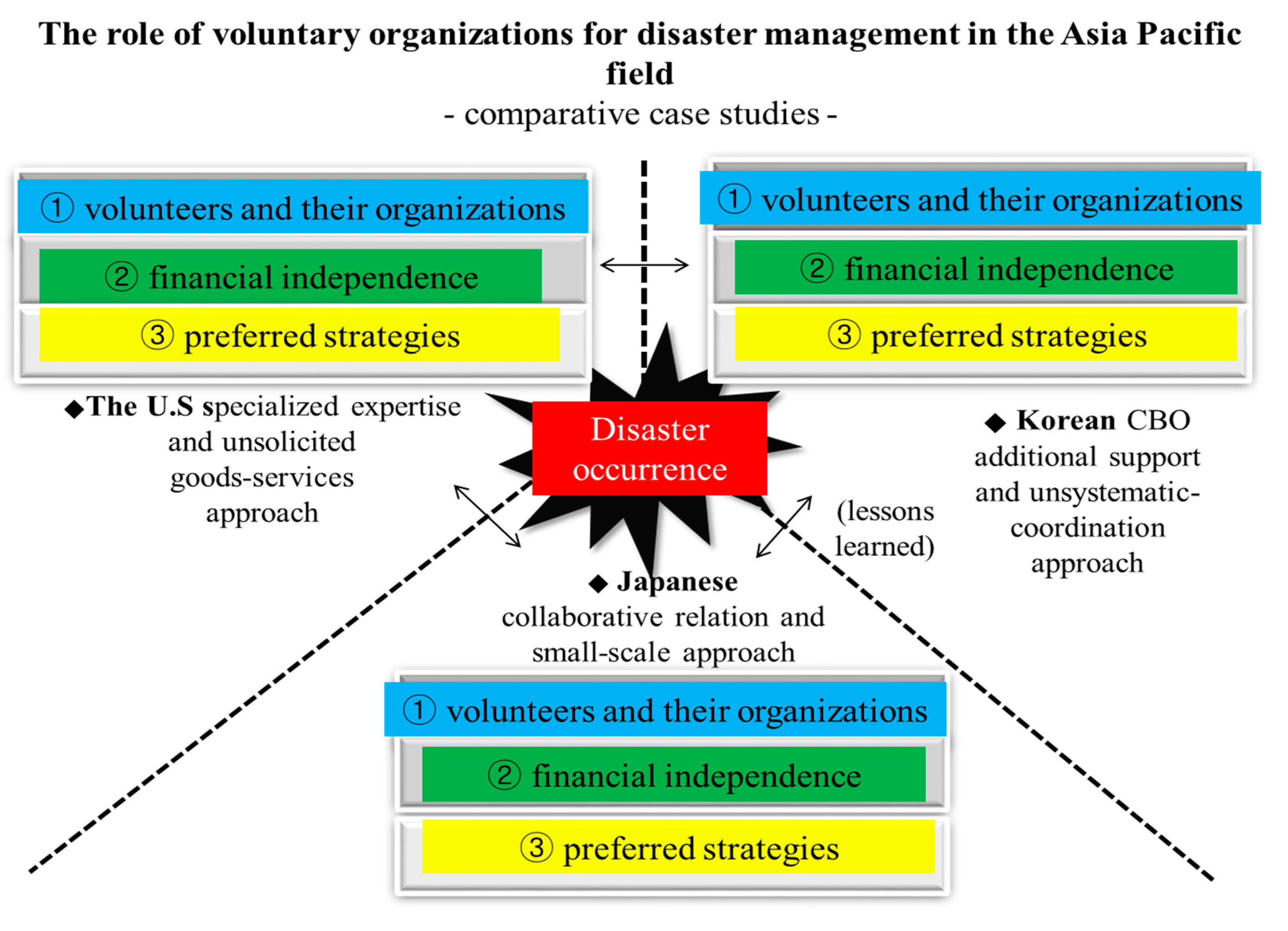

4. U.S. Specialized Expertise and Unsolicited Goods/Services Approach

4.1. Volunteers and Their Organizations

4.2. Financial Independence

4.3. Preferred Strategies

5. Japanese Collaborative Relations and Small-Scale Approach

5.1. Volunteers and Their Organizations

5.2. Financial Independence

5.3. Preferred Strategies

6. Korean CBO Additional Support and Unsystematic Coordination Approach

6.1. Volunteers and Their Organizations

6.2. Financial Independence

6.3. Preferred Strategies

7. Major Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, D.; Kanji, N. Non-Governmental Organizations and Development, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 121–141. [Google Scholar]

- Darley, S. Transforming the world and themselves: The learning experiences of volunteers being trained within health and social care charities in England. Volunt. Sect. Rev. 2016, 7, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- During These Uncertain Times, How Can We Help? Available online: https://www.volunteermatch.org/covid19?gclid=CjwKCAjw5Ij2BRBdEiwA0Frc9VzHo6417AAt6NyU0NBMnpuZySQp9uiM5TvcAKGn0U7O7KDwSXHc4BoCJr0QAvD_BwE (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Penuel, K.B.; Statler, M. Encyclopedia of Disaster Relief, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2010; pp. 807–819. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo, D. Comparative public administration: Prologue, performance, problems, and promise. In Comparative Public Administration: The Essential Readings, 1st ed.; Otenyo, E.E., Lind, H.S., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 129–170. [Google Scholar]

- Marume, S.B.M.; Jubenkanda, R.R.; Namusi, C.W. Comparative public administration. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Boeije, H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual. Quan. 2002, 36, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, D. The comparative method. In Political Science the State of the Discipline II, 1st ed.; Finifter, A.W., Ed.; American Political Science Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner, R.P. Advantages of the comparative method of anthropology. Cross-Cult. Res. 1977, 12, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, G.M.; Lutterschmidt, W.I.; Hutchison, V.H. The comparative method revisited. BioScience 2002, 52, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rational for the Study of Comparative Education. Available online: http://camponotes.blogspot.kr/2013/01/rationale-for-study-of-comparative.html (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- The Disaster Management Cycle. Available online: http://www.gdrc.org/uem/disasters/1-dm_cycle.html (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Roth, S. Aid work as edgework—Voluntary risk-taking and security in humanitarian assistance, development and human rights work. J. Risk Res. 2015, 18, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volunteering in the United States. 2015. Available online: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/volun.nr0.htm (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Macpherson, R.I.S.; Burkle, F.M. Humanitarian aid workers: The forgotten first responders. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan-Saville, J.; Choi, I.; Deady, M.; Scott, P.; Tan, L.; Calvo, R.A.; Bryant, R.A.; Glozier, N.; Harvey, S.B. The impact of trauma exposure on the development of PTSD and psychological distress in a volunteer fire service. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pre-Planning in the World of Volunteer Management. Available online: http://patimes.org/pre-planning-world-volunteer-management/ (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- What is the Voluntary Sector? Available online: https://reachvolunteering.org.uk/guide/what-voluntary-sector (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- How to Get Your First Job in the Charity Sector. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/careers/2017/06/19/how-to-get-your-first-job-in-the-charity-sector/ (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Non-Government Aid Crucial to Disaster Relief Operations. Available online: http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2008/6/1/2008june-nongovernment-aid-crucial-to-disaster-relief-operations (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Johnson, T.R. IIGR Working Paper Series: Disaster Volunteerism, 1st ed.; International Institute of Global Resilience: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- School of Public Policy, University of Maryland. Why Are America’s Volunteers, 1st ed.; Do Good Institute: College Park, MD, USA, 2018; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- UNV. Global Trends in Volunteering Infrastructure, 1st ed.; UNV Programme: Bangkok, Thailand, 2018; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pekkanen, R. Japan’s new politics: The case of the NPO law. J. Jpn. Stud. 2000, 26, 111–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, T. Against the drive for institutionalization: Two decades of disaster volunteers in Japan. In Hazards, Risks and Disasters in Society, 1st ed.; Collins, A., Samantha, J., Manyena, B., Walsh, S., Shroder, J.F., Jr., Eds.; Elsevier: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- McMorran, C. From volunteers to volunteers: Shifting priorities in post-disaster Japan. Jpn. Forum. 2017, 29, 558–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Koike, T.; Hiroki, K.; Toda, T.; Katsube, T. Managing disasters amid COVID-19 pandemic: Approaches of response to flood disasters. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Lam, E.T.C.; Lee, H.-G. Motivation of South Korean volunteers in international sports: A confirmatory factor analysis. Int. J. Volunt. Adm. 2016, 32, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Volunteers Find Scenes of Hope Despair at S. Korea Ferry Site. Available online: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2014/0422/Volunteers-find-scenes-of-hope-despair-at-S.-Korea-ferry-site-video (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Kim, I.-C.; Hwang, C.-S. Defining the Non-profit Sector: South Korea, 1st ed.; The John Hopkins Center for Civil Society Studies: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2002; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Park, C.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Determinants and outcomes of volunteer satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A. Earthquake preparedness and response: Comparison of the United States and Japan. Leadersh. Manag. Eng. 2012, 12, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrick, D. Comparative Case Studies, 1st ed.; UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- National VOAD Committee Manual. Available online: https://3hb3e83lj75i1iikjx1wkj2o-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/NVOAD-Ad-Hoc-Committee-Manual-Apr-2020-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Lee, J.; Fraser, T. How do natural hazards affect participation in voluntary association? The social impacts of disasters in Japanese society. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 34, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SafeNet Forum Is. Available online: http://safenetforum.or.kr/eng/main/main.php?categoryid=02&menuid=01&groupid=00 (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- Rathod, P.B. Comparative Public Administration, 1st ed.; ABD Publishers: New Delhi, India, 2007; pp. 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, D.; Jordan, P.; Halseth, G. The Role of Voluntary Organizations in Rural Canada: Impacts of Changing Availability of Operational and Program Funding, 1st ed.; Canadian Rural Restructuring Foundation: Nelson, BC, Canada, 1999; pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- The Path to Financial Independence in Detail. Available online: https://www.thesimpledollar.com/financial-wellness/the-path-to-financial-independence-in-detail/ (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Wilson, D.C.; Butler, R.J. Voluntary organizations in action; strategy in the voluntary sector. J. Manag. Stud. 1986, 23, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Wilkins, V.M. More similarities or more differences? Comparing public and nonprofit managers’ job motivations. Public Adm. Rev. 2011, 71, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, B. What voluntary activity can and cannot do for America. Public Adm. Rev. 1989, 49, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emergency Management Institute (EMI). Developing and Managing Volunteers, 1st ed.; EMI: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2013; pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Long Term Recovery Guide. Available online: http://www.cadresv.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/long_term_recovery_guide_-_final_20121.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Haddow, G.D.; Bullock, J.A.; Coppola, D.P. Introduction to Emergency Management, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 33–78. [Google Scholar]

- Loehman, E.; Loomis, J. In-stream flow as a public good: Possibilities for economic organization and voluntary local provision. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2008, 30, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voluntary Action Network India (VANI). Enabling Environment for Voluntary Organizations: A Global Campaign, 1st ed.; VANI: New Delhi, India, 2013; pp. 10–47. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, as Amended, and Related Authorities, 1st ed.; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- EMI. The Role of Voluntary Organizations in Emergency Management, 1st ed.; EMI: Emmitsburg, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- National Report of Japan Disaster Reduction for the World Conference on Disaster Reduction (Kobe-Hyogo, Japan 18–22 January 2005). Available online: http://www.unisdr.org/2005/mdgs-drr/national-reports/Japan-report.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Bothwell, R.O. The challenges of growing the NPO and voluntary sector in Japan. In The Voluntary and Non-Profit Sector in Japan: The Challenge of Change, 1st ed.; Osborne, S.P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- Nazarov, E. Emergency Response Management in Japan: Final Research Report, 1st ed.; Asian Disaster Reduction Center: Kobe, Japan, 2011; pp. 5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, I. Roles of volunteers in disaster prevention: Implications of questionnaire and interview surveys. In A Better Integrated Management of Disaster Risks: Toward Resilient Society to Emerging Disaster Risks in Mega-Cities, 1st ed.; Ikeda, S., Fukuzono, T., Sato, T., Eds.; TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; pp. 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. Available online: https://www.cao.go.jp/index-e.html (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Lee, A.-R. Social network model of political participation in Japan. Jpn. J. Political Sci. 2016, 17, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Women’s Network for Disaster Risk Reduction. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/organizations/13363 (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Pharr, S. Conclusion: Targeting by an activist state: Japan as a civil society model. In The State of Civil Society in Japan, 1st ed.; Schwartz, F.J., Pharr, S.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 316–336. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, R. Japan’s civil society from Kobe to Tohoku: Impact of policy changes on government-NGO relationship and effectiveness of post-disaster relief. Electron. J. Contemp. Jpn. Stud. 2015, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Japan’s National Land Agency (JNLA). Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act, 1st ed.; JNLA: Tokyo, Japan, 1997; pp. 1–57.

- ESCAP Annual Report 2014. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/ESCAP-Annual-Report-2014.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Hong, S.; Khim, J.S.; Ryu, J.; Kang, S.-G.; Shim, W.J.; Yim, U.H. Environmental and ecological effects and recoveries after five years of the Hebei Spirit oil spill, Taean, Korea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Voluntary organizations as new street-level bureaucrats: Frontline struggles of community organizations against bureaucratization in a South-Korean welfare-to-work partnership. Soc. Policy Adm. 2013, 47, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA). Available online: http://www.mofa.go.kr/www/index.do (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Korean Red Cross. Available online: https://www.redcross.or.kr/eng/eng_main/main.do (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Bae, Y.; Joo, Y.-M.; Won, S.-Y. Decentralization and collaborative disaster governance: Evidence from South Korea. Habitat Int. 2016, 52, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS). Available online: https://www.mois.go.kr/frt/a01/frtMain.do (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Choi, S.O.; Yang, S.-B. Understanding challenges and opportunities in the nonprofit sector in Korea. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2011, 16, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws and Policies Affecting Volunteerism since 2001. Available online: https://www.unv.org/sites/default/files/Volunteerism%20laws%20and%20policies%202009.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2020).

- Rehnborg, S.J.; Bailey, W.L.; Moore, M.; Sinatra, C. Strategic Volunteer Engagement: A Guide for Nonprofit and Public Sector Leaders, 1st ed.; OneStar Foundation: Austin, TX, USA, 2009; pp. 89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, M. Civil society and the state in South Korea. In SAIS U.S.-Korea Yearbook, 1st ed.; Noh, A., Ed.; K-Developedia (KDI School) Repository: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, M.; van de Bunt, G.G.; de Bruijn, J. Comparative research: Persistent problems and promising solutions. Int. Sociol. 2006, 21, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why You Need to Learn from Your Mistakes. Available online: http://elitedaily.com/life/why-you-need-to-learn-from-your-mistakes/ (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Nakayachi, K.; Ozaki, T. A method to improve trust in disaster risk managers: Voluntary action to share a common fate. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2014, 10, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, S. The global standardization of regional disaster risk management. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2014, 27, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.; Goda, K. From disaster to sustainable civil society: The Kobe experience. Disasters 2004, 28, 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carafano, J.J. The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake: Assessing Disaster Response and Lessons for the United States, 1st ed.; Heritage Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Palttala, P.; Boano, C.; Lund, R.; Vos, M. Communication gaps in disaster management: Perceptions by experts from governmental and non-governmental organizations. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2012, 20, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharing Experiences with Others Makes Them More Intense: Carrying Out Tasks in a Group Amplifies How They Make You Feel. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2785035/Sharing-experiences-makes-INTENSE-Carrying-tasks-group-amplifies-make-feel.html (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- United Nations Volunteers (UNV). Assessing the Contribution of Volunteering to Development: A Participatory Methodology, 1st ed.; UNV: Bonn, Germany, 2011; pp. 18–47. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, J.; McLennan, B.; Handmer, J. A review of informal volunteerism in emergencies and disasters: Definition, opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 13, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.S.; Sakar, B.; Tayyab, M.; Saleem, M.W.; Hussain, A.; Ullah, M.; Omair, M.; Iqbal, M.W. Large-scale disaster waste management under uncertain environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nation/Approach | (1) United States/Specialized Expertise and Unsolicited Goods/Services Approach | (2) Japan/Collaborative Relations and Small-Scale Approach | (3) Korea/CBO Additional Support and Unsystematic Coordination Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | - Not applicable. | - Similarly to Japan, the U.S. government should strengthen its collaboration with voluntary organizations for disaster management by emphasizing its proactive support. - Local voluntary organizations in the United States may consider further expanding their activities in the international community. | - Following Korea, the United States may further incorporate the role of CBOs into disaster management. - The United States may increase its broadcast of the disaster response or recovery phase on television, the Internet, or other platforms. |

| Japan | - Similarly to the United States, Japan should encourage each voluntary organization for disaster management to develop more specialized expertise. - Japan may upgrade its DCBA to the level of the U.S. NRF. | - Not applicable. | - Similarly to Korea, Japan may expand its small-scale management by relying on informal communication channels among voluntary organizations for disaster management. - Japan should more substantially systematize its national networks. |

| Korea | - Korea must consider the U.S. approach of specialized expertise and unsolicited goods/services to be among its concerns in the field. - KDSN needs to decrease the extent of overlapping activities among voluntary organizations following the U.S. NVOAD. | - Korea should try to internationalize the activities of its voluntary organizations for disaster management, as in the case of Japan. - Korean voluntary organizations for disaster management may also consider providing low-cost services in the field to achieve financial independence, similarly to Japan. | - Not applicable. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jung, D.-Y.; Ha, K.-M. A Comparison of the Role of Voluntary Organizations in Disaster Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041669

Jung D-Y, Ha K-M. A Comparison of the Role of Voluntary Organizations in Disaster Management. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041669

Chicago/Turabian StyleJung, Do-Young, and Kyoo-Man Ha. 2021. "A Comparison of the Role of Voluntary Organizations in Disaster Management" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041669

APA StyleJung, D.-Y., & Ha, K.-M. (2021). A Comparison of the Role of Voluntary Organizations in Disaster Management. Sustainability, 13(4), 1669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041669