Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business in the Time of COVID-19: Changing Strategy?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility in Family Business

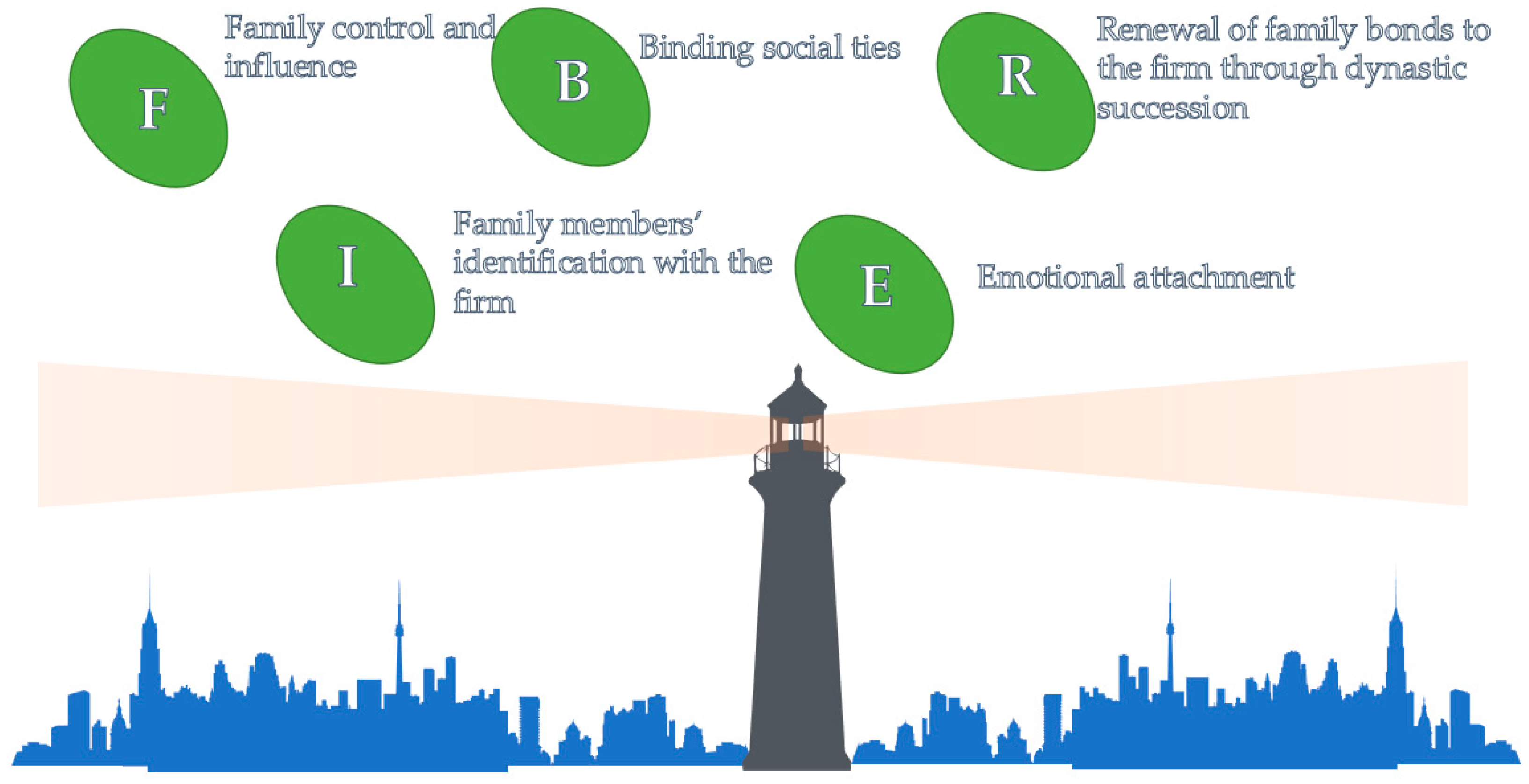

2.2. Socioemotional Wealth, Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business

3. Methodology, Findings and Discussion

3.1. Are We Witnessing a Reinvention of Corporate Social Responsibility within the Framework of Family Businesses Because of the Global Pandemic?

- Providing logistical support to the government to purchase and supply essential sanitary equipment.

- The company Inditex (Spain) made its logistical capacity available to the Spanish health authorities for acquiring and transporting sanitary equipment and provided 35 million units of health-protection materials from China. These purchases were made not only by Inditex and the Amancio Ortega Foundation but also by the Government of Spain, autonomous communities and hospitals.

- LVMH (France) secured an order with a Chinese industrial supplier for 7 million surgical masks and 3 million FFP2 masks for France.

- Restructuring production plants and directing lines to the health-care field by manufacturing protective equipment, ventilators and disinfectant gel.

- The LVMH family group remodeled its perfume- and cosmetic-production units to manufacture and distribute hydroalcoholic disinfectant gels for free.

- The L’Oréal group (France) also remodeled its production units to collaborate with European health authorities and manufacture hand-sanitizer gel.

- The Antolín Group (Spain), a Spanish family business specializing in automotive interior components, contributed to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic by manufacturing components for protective screens as well as protective gowns for health personnel.

- Avoiding temporary layoffs as a supportive measure for employees and their communities’ economies, which returns the focus to the owner family that controls the company and has decided to think more about the long-term and its employees than its financial results.

- On 17 March, the Inditex Group temporarily closed 3785 stores in 39 countries, but it decided not to apply temporary employment regulation files (ERTE in Spanish) to its workers and instead continued to pay its workers a full salary.

- Similarly, Hijos de Rivera, the family business owner of Estrella Galicia, decided not to apply ERTE to its staff because, in the words of its CEO Ignacio Rivera, “You have to be supportive in this pandemic, pull out all the stops, and protect this great family that are our workers.”

- Help suppliers by reducing payment periods.

- The L’Oréal group decided to make payments immediately to help its suppliers during the possible economic slowdown resulting from the pandemic.

- Mercadona, a Spanish supermarket chain, also helped its suppliers by injecting liquidity through an extension of its confirming lines worth up to 2.1 billion euros so that these companies could collect their bills on the spot and maintain employment.

- Purely philanthropic activities such as donating millions of dollars or euros in response to the coronavirus, allowing for greater investment into the research and development of treatments and a vaccine for COVID-19, as well as donations in kind (with an example from Big Charitable Gifts, www.philantrophy.com, accessed on 9 December 2020):

- “All In Washington Fund (Seattle): $25 million challenge pledge from Jeff Bezos to match gifts of under $1 million apiece from other donors who give to the fund’s efforts to provide immediate support for people who have been affected by the coronavirus pandemic across Washington State. Bezos founded Amazon.”

- “Covid-19 Therapeutics Accelerator (Seattle) has received a pledge of $20 million from the billionaires Michael and Susan Dell through their foundation. This effort was created in March by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and others to speed up the development of treatments for Covid-19 patients and make it easier for those with the disease to access treatment. Michael Dell founded and leads the technology company Dell, in Austin, TX, USA.”

3.2. Does This New Trend Deserve Support, Given the Fundamental Role That Family Businesses Have Played in This Situation?

3.3. If So, What Should Such Support Consist of, and What Is the Optimal Channel for Articulating It?

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bammens, Y.; Voordeckers, W.; Van Gils, A. Boards of Directors in family businesses: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivo-López, E.; Villanueva-Villar, M.; Vaquero-García, A.; Lago-Peñas, S. Do family firms contribute to job stability? Evidence from the great recession. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivo-López, E.; Villanueva-Villar, M.; Suárez-Blázquez, G.; Reyes-Santías, F. How does a business family manage its wealth? A family office perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 1, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hategan, C.D.; Sirghi, N.; Curea-Pitorac, R.I.; Hategan, V.P. Doing well or doing good: The relationship between corporate social responsibility and profit in Romanian companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. European Competitiveness Report (2008); European Commission: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, P.; Presas, P.; Simon, A. The heterogeneity of family firms in CSR engagement: The role of values. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 206–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- López Pérez, M.V.; García Santana, A.; Rodríguez Ariza, L. Sustainable Development and Corporate Efficiency: A Study Based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmiri, S.; Mahajan, V. Beating the recession blues: Exploring the link between family ownership, strategic marketing behavior and firm performance during recessions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2014, 31, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Villar, M.; Rivo-López, E.; Lago-Peñas, S. On the relationship between corporate governance and value creation in an economic crisis: Empirical evidence for the Spanish case. Bus. Res. Quart. 2016, 19, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deniz, M.; Suarez, M. Corporate social responsibility and family business in Spain. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 56, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; Van Rossem, A.; Buelens, M. Small-business owner-managers’ perceptions of business ethics and CSR-related concepts. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 425–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campopiano, G.; De Massis, A. Corporate social responsibility reporting: A content analysis in family and non-family firms. J. Bus Ethics 2015, 129, 511–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Chrisman, J.J.; Spence, L.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder salience in family firms. Bus. Ethics Quart. 2011, 21, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, E.; Kassinis, G.; Filotheou, A. Downsizing and stakeholder orientation among the fortune 500: Does family ownership matter? J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlaner, L.M.; Berent-Braun, M.M.; Jeurissen, R.J.M.; de Wit, G. Beyond size: Predicting engagement in environmental management practices of dutch SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gils, A.; Dibrell, C.; Neubaum, D.O.; Craig, J.B. Social issues in the family enterprise. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2014, 27, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sageder, M.; Mitter, C.; Feldbauer-Durstmueller, B. Image and reputation of family firms: A systematic literature review of the state of research. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 335–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Boyle, E.H., Jr.; Rutherford, M.W.; Pollack, J.M. Examining the relation between ethical focus and financial performance in family firms: An exploratory study. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2010, 23, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.D.D.; Je-Yen, T.; Rajangam, N. Board composition and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu, N.; Botero, I.C. Philanthropy in family enterprises: A review of literature. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 29, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.C. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and sustainable financial performance: Firm-level evidence from taiwan. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiklund, J. Commentary: “Family firms and social responsibility: Preliminary evidence from the S&P 500”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madison, K.; Holt, D.T.; Kellermanns, F.W.; Ranft, A.L. Viewing family firm behavior and governance through the lens of agency and stewardship theories. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 29, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, G.; Gray, S.J. Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2010, 19, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; García-Sánchez, I.M. The role of independent directors at family firms in relation to corporate social responsibility disclosures. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Strategic management of the family business: Past research and future challenges. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.C.; Reeb, D.M. Board composition: Balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 2004, 49, 209–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Larraza-Kintana, M. Socio-emotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Adm. Sci. Q. 2010, 55, 82–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.L.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shepherd, D.A. An emotions perspective for advancing the fields of family business and entrepreneurship: Stocks, flows, reactions, and responses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2016, 29, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Galdeano, L.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Cruz, C.; Contín-Pilart, I. Just about money? CEO satisfaction and firm performance in small family firms. Small Bus. Econom. 2017, 49, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D.J. Exploring the effects of using consumer culture as a unifying pedagogical framework on the ethical perceptions of MBA students. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2012, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, J.; Picazo-Tadeo, A.; Rojas, M. Economic crisis and well-being in Europe: Introduction. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 120, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahneman, D.; Wakker, P.; Sarin, R. Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility. Q. J. Econom. 1997, 112, 375–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cennamo, C.; Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gómez-Mejía, L.R. Socioemotional wealth and proactive stakeholder engagement: Why family-controlled firms care more about their stakeholders. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional wealth in family firms: Theoretical dimensions, assessment approaches, and agenda for future research. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hou, W.; Li, W.; Wilson, C.; Wu, Z. Family control, regulatory environment, and the growth of entrepreneurial firms: International evidence. Corp. Gov. An Int. Rev. 2014, 22, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Fairclough, S.; Dibrell, C. Attention, action, and greenwash in family-influenced firms? Evidence from polluting industries. Organ. Environ. 2017, 30, 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binz, C.A.; Ferguson, K.E.; Pieper, T.M.; Astrachan, J.H. Family business goals, corporate citizenship behaviour and firm performance: Disentangling the connections. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Dev. 2017, 16, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, S. Drivers of proactive environmental strategy in family firms. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vardaman, J.M.; Gondo, M.B. Socioemotional wealth conflict in family firms. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1317–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.; Laksmana, I. The impact of corporate social responsibility on risk taking and firm value. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B.; Cao, C.X.; Chen, C. Corporate social responsibility, firm value, and influential institutional ownership. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 52, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Conflict between Shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2011. Available online: http://hbr.org/2011/01/the-big-idea-creatingshared-value (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Cruz, C.; Berrone, P.; De Castro, J. The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 653–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Larraza-Kintana, M.; Garcés-Galdeano, L.; Berrone, P. Are family firms really more socially responsible? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1295–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gehringer, T. Corporate Foundations as Partnership Brokers in Supporting the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2020, 12, 7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Mozos, E.; García-Muiña, F.E.; Fuentes-Moraleda, L. Application of Ecosophical Perspective to Advance to the SDGs: Theoretical Approach on Values for Sustainability in a 4S Hotel Company. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Ding, H.B.; Chung, H.M. Corporate social responsibility performance in family and non-family firms: The perspective of socio-emotional wealth. Asian Bus. Manag. 2015, 14, 383–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palencia-Lefler Ors, M. Donación, mecenazgo y patrocinio como técnicas de relaciones públicas al servicio de la responsabilidad social corporativa. Anàlisi 2007, 35, 153–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, N.; Sharma, P.; Ramachandran, K. Spirituality and Corporate Philanthropy in Indian Family Firms: An Exploratory Study. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author; Date | Journal, JCR List Rankings & Citations | Method and Sample | Theoretical Perspective | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | Journal of Business Ethics (Q1 Ethics, Q2 Finance); 142 | Quantitative: survey of 112 Spanish family firms; cross-sectional | Corporate social responsibility approach | FF are not a homogeneous group, and the differences in perceptions towards CSR do not seem to be associated with biographical characteristics. |

| [12] | Journal of Business Ethics (Q1 Ethics, Q2 Finance); 110 | Quantitative: 450 Malaysian family firms | Kelly’s personal construct theory | Small business owner-managers differentiate among the various concepts related to corporate responsibility and business ethics but at the same time recognize the interrelationships and interdependencies of these concepts. |

| [13] | Journal of Business Ethics (Q1 Ethics, Q2 Finance); 106 | Qualitative: CSR reports of 24 family firms and 74 nonfamily enterprises; content analysis and statistical inference | Institutional theory | Family firms disseminate a greater variety of CSR reports, are less compliant with CSR standards and place emphasis on different CSR topics. |

| [14] | Business Ethics Quarterly (Q1 Ethics; Q2 Business); 104 | Conceptual | Stakeholder theory; socioemotional wealth | Normative power is more typical in family business stakeholder salience; for family stakeholders, legitimacy is based on heredity, and both are linked in the family business case because of family ties and family-centered noneconomic goals. |

| [15] | Journal of Business Ethics (Q1 Ethics, Q2 Finance); 86 | Quantitative: 90 family firms and 90 nonfamily firms on the Fortune 500 list | Stakeholder theory | Family businesses do downsize less regardless of financial performance considerations. However, their actions are not related to their employees. |

| [7] | Family Business Review (Q1 Business); 79 | Qualitative: interpretative and 12 case studies of Spanish family firms | Stewardship theory; socioemotional wealth | This article identifies the connection between family involvement and CSR engagement by means of the values that a family transfers to a family firm. |

| [16] | Journal of Business Ethics (Q1 Ethics, Q2 Finance); 78 | Quantitative: 689 Dutch SMEs | Theory of planned behavior | Several endogenous factors, including tangibility of a sector, firm size, innovative orientation, family influence and perceived financial benefits from energy conservation, predict an SME’s level of engagement in selected environmental management practices. For family influence, this effect is found only in interaction with the number of owners. |

| [17] | Family Business Review (Q1 Business); 56 | Review: 35 articles | Social identity theory, stewardship theory, agency theory, behavioral agency model, stakeholder theory, institutional theory, social exchange theory, sustainable family business theory and the resource-based view | This article suggest future research questions on the social issues of family business interface. |

| [18] | Review of Managerial Science (Q1 Management); 50 | Review of literature: 73 papers | Organizational identity theory, socioemotional wealth, the resource-based view, agency theory and brand-identity theory | Family firms enjoy favorable reputations compared with nonfamily firms and help create competitive advantages. |

| [19] | Family Business Review (Q1 Business); 41 | Quantitative: 526 US small family firms | Stewardship theory | This article observes the relation between family involvement and a firm’s ethical focus. Increased ethical focus predicted increased financial performance. |

| [20] | Corporate Governance:-The International Journal of Business in Society (Emerging); 36 | Quantitative: 450 Malaysian companies | Agency theory | The presence of women directors affects the level of CSR initiatives. A positive relationship exists between nonexecutive directors and CSR initiatives in nonfamily businesses, and a negative relationship exists between independent nonexecutive directors and CSR for family-controlled businesses. |

| [21] | Family Business Review (Q1 Business); 33 | Literature review: 55 articles | Agency theory, enlightened self-interest model, organizational identity, social capital, socioemotional wealth (SEW), stakeholder identity orientation, stakeholder, stewardship, sustainable family business | This review synthesizes the current knowledge of philanthropic practices of family enterprises from both academic and practitioner points of view. |

| [22] | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management (Q1 Business Q1 Environmental Studies Q1 Management); 30 | Quantitative: firms listed on the TWSE | Stakeholder theory | Socially responsible firms can achieve financial results superior to those of firms that do not pursue CSR initiatives. There are differences in the results for electronics and non-electronics industries. For the non-electronics industries, board ownership has a significant positive influence on the CSR–CFP relationship, and there is a negative relationship with a family business. |

| [23] | Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice (Q1 Business); 27 | Conceptual | Agency theory | Agency theory can lead to additional valuable insights about CSR in family firms. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivo-López, E.; Villanueva-Villar, M.; Michinel-Álvarez, M.; Reyes-Santías, F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business in the Time of COVID-19: Changing Strategy? Sustainability 2021, 13, 2041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042041

Rivo-López E, Villanueva-Villar M, Michinel-Álvarez M, Reyes-Santías F. Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business in the Time of COVID-19: Changing Strategy? Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042041

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivo-López, Elena, Mónica Villanueva-Villar, Miguel Michinel-Álvarez, and Francisco Reyes-Santías. 2021. "Corporate Social Responsibility and Family Business in the Time of COVID-19: Changing Strategy?" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2041. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042041