To Dine, or Not to Dine on a Cruise Ship in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Tripartite Approach towards an Understanding of Behavioral Intentions among Female Passengers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dining Experiencescape

2.2. The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)

2.3. The Prospect Theory

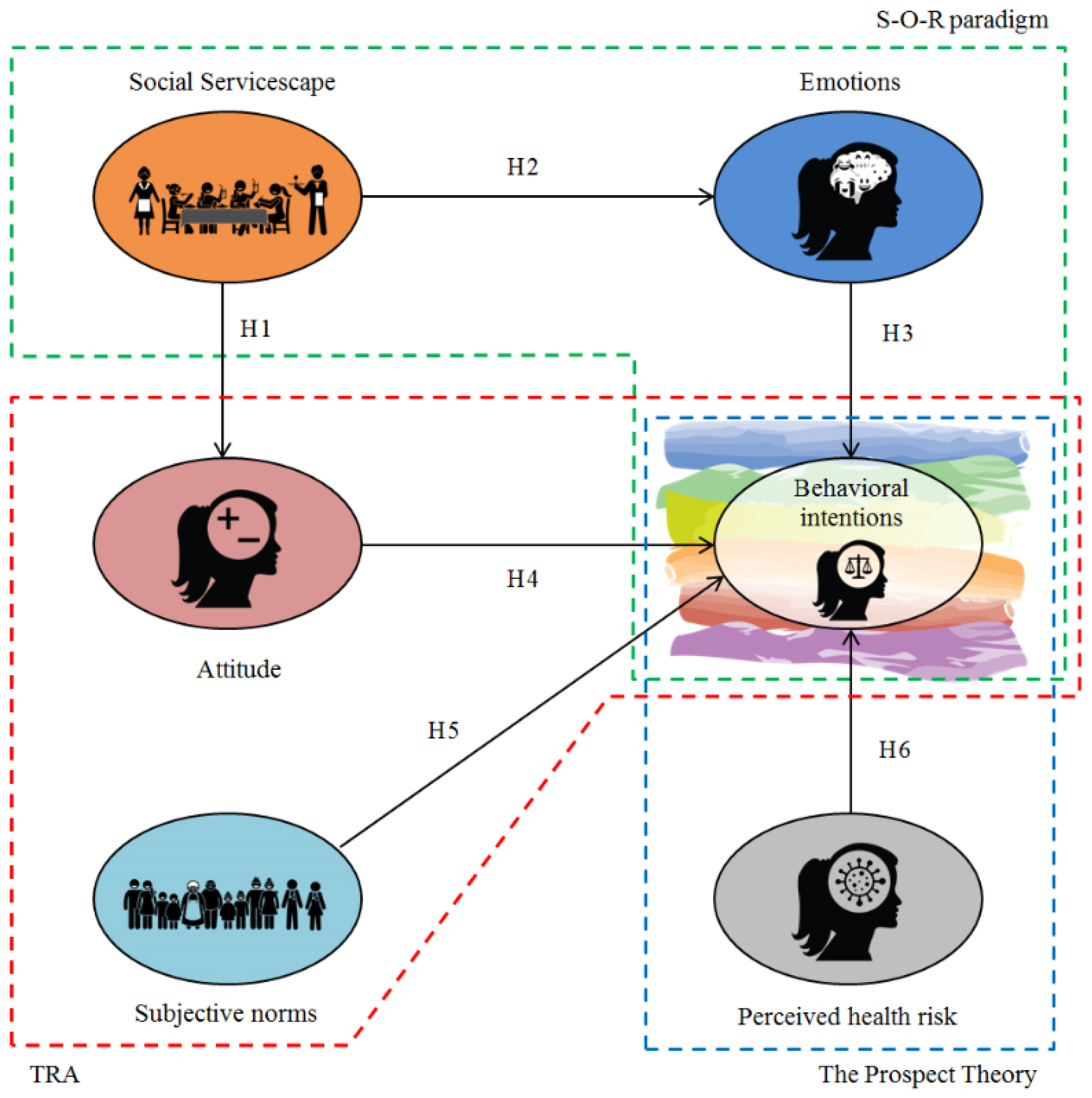

2.4. Hypotheses

2.4.1. The Social Servicescape, Emotions and Behavioral Intentions

2.4.2. Attitude, Subjective Norms and Behavioral Intentions

2.4.3. Perceived Health Risk of COVID-19 and Behavioral Intentions

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Collection Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Assessment

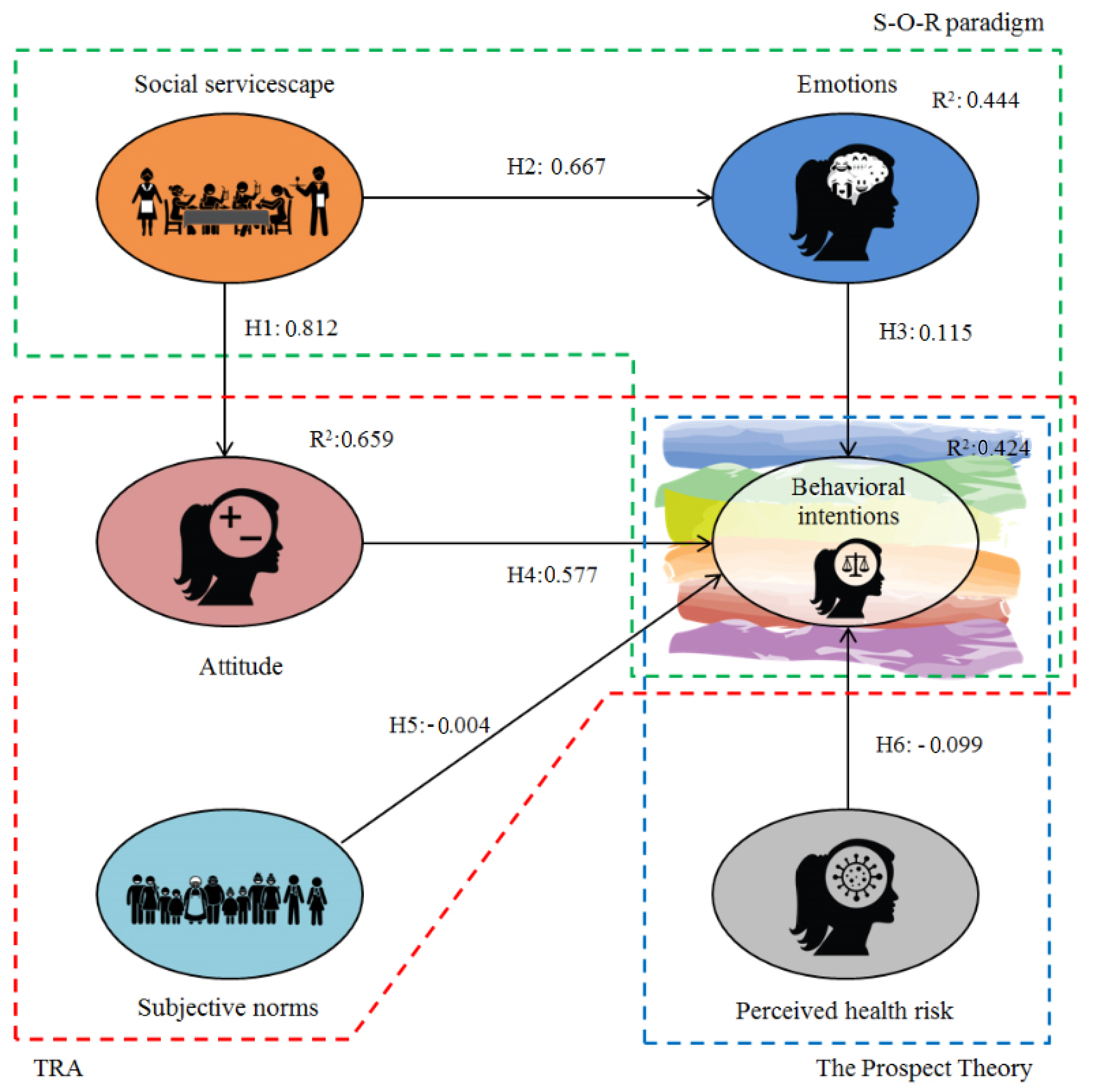

4.2. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

- (1)

- Terminate refers to all known methods to eliminate any opportunity of spreading of COVID-19 (e.g., health screening of guests and crew prior to boarding and during the cruise, negative PCR test prior to boarding and during the cruise if needed and sailing with reduced capacities).

- (2)

- Bifurcate refers to maintaining physical distancing while being on board (e.g., enforcing the physical distancing of 2 m between guests and between guests and the crew).

- (3)

- Isolate refers to wearing face coverings while being on board except when eating or drinking (e.g., in dining rooms, servers should wear face coverings together with a face shield, or at purser desks, physical barriers between guests and the crew should be installed (for close interaction with less than 1 m distance)).

- (4)

- Disable refers to hygiene practices (hand washing and hand sanitizers) and increased cleaning and sanitizing frequencies of hard surfaces.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs and Items | Loadings | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social servicescape | |||

| Strongly Disagree (1)—Strongly Agree (5) | |||

| 0.688 | 4.11 | 0.616 |

| 0.717 | 4.09 | 0.642 |

| 0.575 | 4.14 | 0.572 |

| Emotions | |||

| 0.804 | 4.39 | 0.539 |

| 0.840 | 4.49 | 0.521 |

| Attitude | |||

| Dining at this cruise dining place in the future is | |||

| 0.640 | 6.03 | 0.656 |

| 0.618 | 6.53 | 0.628 |

| 0.654 | 6.12 | 0.454 |

| Subjective norms | |||

| Strongly Disagree (1)—Strongly Agree (5) | |||

| 0.660 | 3.07 | 0.813 |

| 0.722 | 2.59 | 0.710 |

| Perceived health risk | |||

| Strongly Disagree (1)—Strongly Agree (5) | |||

| 0.918 | 2.49 | 0.652 |

| 0.917 | 2.32 | 0.679 |

| 0.992 | 2.41 | 0.670 |

| Behavioral intentions | |||

| Strongly Disagree (1)—Strongly Agree (5) | |||

| 0.836 | 4.60 | 0.521 |

| 0.833 | 4.59 | 0.537 |

| 0.654 | 4.22 | 0.533 |

References

- Radic, A. Towards an understanding of a child’s cruise experience. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Lines International Association. 2020 State of the Cruise Industry Outlook. Available online: https://cruising.org/en/news-and-research/press-room/2019/december/clia-releases-2020-state-of-the-cruise-industry-outlook-report (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Statista Research Department. Expected Passenger Cruise Capacity in Operation Worldwide from May 2020 to January 2021, by Month. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1119828/cruise-capacity-in-operation-forecast-monthly/ (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Cruise Market Watch. Growth of the Ocean Cruise Line Industry. Available online: https://cruisemarketwatch.com/growth/ (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Cruise Industry News. Cruise Ships Back in Service January 2021 Update. Available online: https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/24135-cruise-ships-back-in-service-january-2021-update.html (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Lück, M.; Seeler, M.; Radic, A. Hitting the reset button for post-COVID-19 cruise tourism: The case of Akaroa, New Zealand. Acad. Lett. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cruise Industry News. Here’s How Much Cash the Cruise Lines Are Burning Through. Available online: https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/23908-here-are-the-cruise-lines-operating-right-now.html (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Radic, A.; Law, R.; Lück, M.; Kang, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Arjona-Fuentes, J.-M.; Han, H. Apocalypse Now or Overreaction to Coronavirus: The Global Cruise Tourism Industry Crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Nicolau, J.L. An open market valuation of the effects of COVID-19 on the travel and tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 83, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdmann, F. Amid Order Shifts, Cutbacks, Cruise Market will Need a Decade to Recover: Bernard Meyer. Available online: https://www.seatrade-cruise.com/news/amid-order-shifts-cutbacks-cruise-market-will-need-decade-recover-bernard-meyer (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Framework for Conditional Sailing and Initial Phase COVID-19 Testing Requirements for Protection of Crew. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/pdf/CDC-Conditional-Sail-Order_10_30_2020-p.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Second Modification and Extension of No Sail Order and Other Measures Related to Operations. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/pdf/No-Sail-Order-Cruise-Ships-Second-Extension_07_16_2020-p.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Bennett, M. Competing with the Sea: Contemporary cruise ships as omnitopias. PAJ 2016, 21, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallani, S.S. Mediating cultural encounters at sea: Dining in the modern cruise industry. J. Tour. Hist. 2017, 9, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallani, S.S. The world on a ship: Producing cosmopolitan dining on mass-market cruises. Food Cult. Soc. 2019, 22, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Hu, L.; Hung, K.; Mao, Z. Assessing servicescape of cruise tourism: The perception of Chinese tourists. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2556–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, A.; Popesku, J. Quality of cruise experience: Antecedents and consequences. Teme 2018, 42, 523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Li, M.; Wu, M. Performing femininity: Women at the top (doing and undoing gender). Tour. Manag. 2020, 80, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durko, A.M.; Stone, M.J. Even lovers need a holiday: Women’s reflections of travel without their partners. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 21, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrusciel, B. Best Cruises for Single Women. Available online: https://www.cruisecritic.com/articles.cfm?ID=3457 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Cruise Lines International Association. 2019 Cruise, Trends & Industry Outlook. Available online: https://cruising.org/-/media/eu-resources/pdfs/CLIA%202019-Cruise-Trends--Industry-Outlook (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Figueroa-Domecq, C.; Pritchard, A.; Segovia-Perez, M.; Morgan, N.; Villace-Moliero, T. Tourism gender research: A critical accounting. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, L.; Osman, H. The female tourist experience in Egypt as Islamic destination. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 63, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. Consumer attitudes and behavior: The theory of planned behavior applied to food consumption decisions. Ital. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2016, 70, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, M.; Muskat, B.; Ritchie, B. Which travel risks are more salient for destination choice? An examination of the tourist’s decision-making process. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 10487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruise Industry News. Norwegian to Have Trial Cruises as Early as January. Available online: https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/23844-norwegian-to-have-trial-cruises-as-early-as-january.html (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Brooks, D.J.; Saad, L. The COVID-19 Responses of Men vs. Women. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/321698/covid-responses-men-women.aspx (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pizam, A.; Tasci, A.D. Experienscape: Expanding the concept of servicescape with a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach (invited paper for ‘luminaries’ special issue of International Journal of Hospitality Management). Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Didelot, X.; Yang, J.; Wong, G.; Shi, Y.; Liu, W.; Gao, F.; Bi, Y. Inference of person-to-person transmission of COVID-19 reveals hidden super-spreading events during the early outbreak phase. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Line, N.D. The restaurant social servicescape: Establishing a nomological framework. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calza, F.; Pagliuca, M.; Risitano, M.; Sorrentino, A. Testing moderating effects on the relationships among on-board cruise environment, satisfaction, perceived value and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 934–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, M.W.; Yeh, S.-S.; Fan, Y.-L.; Huan, T.-C. The effect of cuisine creativity on customer emotions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 85, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Martin Fishbein’s Legacy: The Reasoned Action Approach. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2012, 640, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Andreu, L.; Huang, S. Millenials’ intentions to book on Airbnb. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 22, 2284–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Pinto, P.; Silva, J.A.; Woosnam, K.Y. Residents’ attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviours: The case of developing island countries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhu, A.; Choi, H.; Bujisic, M.; Bilgihan, A. Satisfaction and positive emotions: A comparison of the influence of hotel guests’ beliefs and attitudes on their satisfaction and emotions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, F.; de Hoog, R. The floating vacationer: Destination choices and the gap between plans and behavior. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.R. A critique of prospect theory and framing with particular reference to consumer decisions. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 1992, 5, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmoulins-Lebeault, F.; Meunier, L.; Ohadi, S. Does Implied Volatility Pricing Follow the Tenets of Prospect Theory? J. Behav. Financ. 2020, 21, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.T.; Al-Ansi, A. Risk assessment of halal products and services: Implication for tourism industry. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 103130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; de Groote, J.; Petrick, J.F.; Lu, T.; Nijkamp, P. Travellers’ willingness to pay and perceived value of time in ride-sharing: An experiment on China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2972–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfagharian, M.; Rajamma, R.K.; Naderi, I.; Torkzadeh, S. Determinants of medical tourism destination selection process. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2018, 27, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, L.; Line, N.; Kim, W.G. The impact of the social servicescape, density, and restaurant type on perceptions of interpersonal service quality. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Choi, K. An investigation on customer revisit intention to theme restaurants: The role of servicescape and authentic perception. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1464–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Cui, M. The role of co-creation experience in forming tourists’ revisit intention to home-based accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.N.; Wei, W.; Hua, N.; Chen, P.-J. Customer emotions minute by minute: How guests experience different emotions within the same service environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.; Bosselman, R. Measuring customer perceptions of restaurant innovativeness: Developing and validating a scale. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 74, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.L.; Ho, J.A.; Sambasivan, M.; Ng, S.I. Antecedents and outcome of job embeddedness: Evidence from four and five-star hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Björk, P.; Coudounaris, D.N. Emotions elicited by local food consumption, memories, place attachment and behavioural intentions. Anatolia 2017, 28, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sok, J.; Borges, J.R.; Schmidt, P.; Ajzen, I. Farmer Behaviour as Reasoned Action: A Critical Review of Research with the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-J. Investigating beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding green restaurant patronage: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Im, J.; Jung, S.E.; Severt, K. The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Esfahani, S.; Kang, J. Why do you use Yelp? Analysis of factors influencing customers’ website adoption and dining behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Roberts, K.R. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict food safety behavioral intention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 90, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.-L.; Tariq, B.; Radic, A.; Park, S.-H. The Post-Coronavirus World in the International Tourism Industry: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Safer Destination Choices in the Case of US Outbound Tourism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cañizares, S.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Muñoz-Fernández, G.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Impact of the perceived risk from Covid-19 on intention to travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kang, J. Reducing perceived health risk to attract hotel customers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Focused on technology innovation for social distancing and cleanliness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.; Stockton, S. Smooth sailing! Cruise passengers’ demographics and health perceptions while cruising the Eastern Caribbean. Int. J. Bus. 2013, 4, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J. Risk perceptions of health and safety in cruising. AIMS Geosci. 2020, 6, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J. The Latest on the SeaDream 1 COVID-19 Debacle—What Went Wrong. Available online: https://www.cruiselawnews.com/2020/11/articles/disease/the-latest-on-the-seadream-1-covid-19-debacle-what-went-wrong/ (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Bryant, S. Just Back from SeaDream: Lessons the Cruise Industry Can Learn from A COVID-Interrupted Trip. Available online: https://www.cruisecritic.com/articles.cfm?ID=5744 (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 and Cruise Ship Travel. Available online: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/covid-4/coronavirus-cruise-ship (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Dataessential Report. COVID-19 Report 40: Winter is Coming. Available online: https://datassential.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Datassential-Coronavirus40-11-13-20.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2020).

- Teeroovengadum, V.; Nunkoo, R. Sampling design in tourism and hospitality research. In Handbook of Research Methods for Tourism and Hospitality Management; Nunkoo, R., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 477–488. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Olya, H.G.T.; Han, H. Effect of general risk on trust, satisfaction, and recommendation intention for halal food. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 83, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, A.; Björk, P.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H. Cruise Holidays: How On-Board Service Quality Affects Passengers’ Behavior. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2019, 14, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and the recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terglav, K.; Ruzzier, M.K.; Kaše, R. Internal branding process: Exploring the role of mediators in top management’s leadership–commitment relationship. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneshensel, C.S. Theory-Based Data Analysis for the Social Science, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cruise Industry News. Royal Caribbean Sees 100,000 Sign Ups for Free Volunteer Cruises. Available online: https://www.cruiseindustrynews.com/cruise-news/23878-royal-caribbean-sees-100-000-sign-ups-for-free-volunteer-cruises.html (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Kiefer, P. Will We Ever Trust Crowds Again? Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/09/coronavirus-will-we-ever-trust-crowds-again-cvd (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviors: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 70–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasci, A.D.; Pizam, A. An expanded nomological network of experienscape. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 32, 999–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, K.; Arcodia, C. A systematic literature review of risk and gender research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Carnival Cruise Dining | https://www.facebook.com/groups/566712757126641 |

| Princess Cruises—Passenger Forum | https://www.facebook.com/groups/771427119576844 |

| Celebrity Cruises | https://www.facebook.com/CelebrityCruises |

| Royal Caribbean Cruising | https://www.facebook.com/groups/royalcaribbeancruising |

| MSC Cruises Fan Page | https://www.facebook.com/groups/271237986384019 |

| Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) Latitudes Members | https://www.facebook.com/groups/latitudeshq |

| Holland America Line Fans | https://www.facebook.com/HALCruises |

| Costa Cruise Lines Fans | https://www.facebook.com/groups/CostaCruisesFans |

| P&O Cruises—UK Fan Page | https://www.facebook.com/groups/pandocruises |

| Cruise Foodies | https://boards.cruisecritic.com/forum/125-cruise-foodies/ |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived health risk | 1.000 | 0.889 | 0.960 | |||||

| 2. Social servicescape | −0.041 | 1.000 | 0.439 | 0.700 | ||||

| 3. Behavioral intentions | −0.051 | 0.390 | 1.000 | 0.584 | 0.805 | |||

| 4. Attitude | 0.081 | 0.605 | 0.670 | 1.000 | 0.406 | 0.672 | ||

| 5. Subjective norms | 0.016 | −0.293 | −0.258 | −0.365 | 1.000 | 0.478 | 0.647 | |

| 6. Emotions | 0.172 | 0.433 | 464 | 0.749 | −0.418 | 1.000 | 0.676 | 0.807 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Coefficients | t-Values | Significant | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 H2 | Social servicescape Social servicescape | → → | Attitude Emotions | 0.812 0.667 | 7.746 ** 7.978 ** | Yes Yes |

| H3 | Emotions | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.115 | 1.612 | No |

| H4 | Attitude | → | Behavioral intentions | 0.577 | 6.368 ** | Yes |

| H5 H6 | Subjective norms Perceived health risk | → → | Behavioral intentions Behavioral intentions | −0.004 −0.099 | −0.055 −2.075 * | No Yes |

| Total variance explained: R2 for Emotions = 0.444 R2 for Attitude = 0.659 R2 for Behavioral intentions = 0.424 | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radic, A.; Lück, M.; Al-Ansi, A.; Chua, B.-L.; Seeler, S.; Raposo, A.; Kim, J.J.; Han, H. To Dine, or Not to Dine on a Cruise Ship in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Tripartite Approach towards an Understanding of Behavioral Intentions among Female Passengers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052516

Radic A, Lück M, Al-Ansi A, Chua B-L, Seeler S, Raposo A, Kim JJ, Han H. To Dine, or Not to Dine on a Cruise Ship in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Tripartite Approach towards an Understanding of Behavioral Intentions among Female Passengers. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052516

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadic, Aleksandar, Michael Lück, Amr Al-Ansi, Bee-Lia Chua, Sabrina Seeler, António Raposo, Jinkyung Jenny Kim, and Heesup Han. 2021. "To Dine, or Not to Dine on a Cruise Ship in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Tripartite Approach towards an Understanding of Behavioral Intentions among Female Passengers" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052516

APA StyleRadic, A., Lück, M., Al-Ansi, A., Chua, B.-L., Seeler, S., Raposo, A., Kim, J. J., & Han, H. (2021). To Dine, or Not to Dine on a Cruise Ship in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Tripartite Approach towards an Understanding of Behavioral Intentions among Female Passengers. Sustainability, 13(5), 2516. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052516