Business Ethics Decision-Making: Examining Partial Reflective Awareness

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Classical Theories in Business Ethics

1.2. Novel Theories in Business Ethics

1.3. Research Gap

- What individuals are thinking versus report they are thinking (reflective awareness);

- What is the relationship between moral judgment and reflective awareness, namely, the differences in reported and observed decisions and behavior, and their reasons;

- How revealed regularities can be translated into nudges.

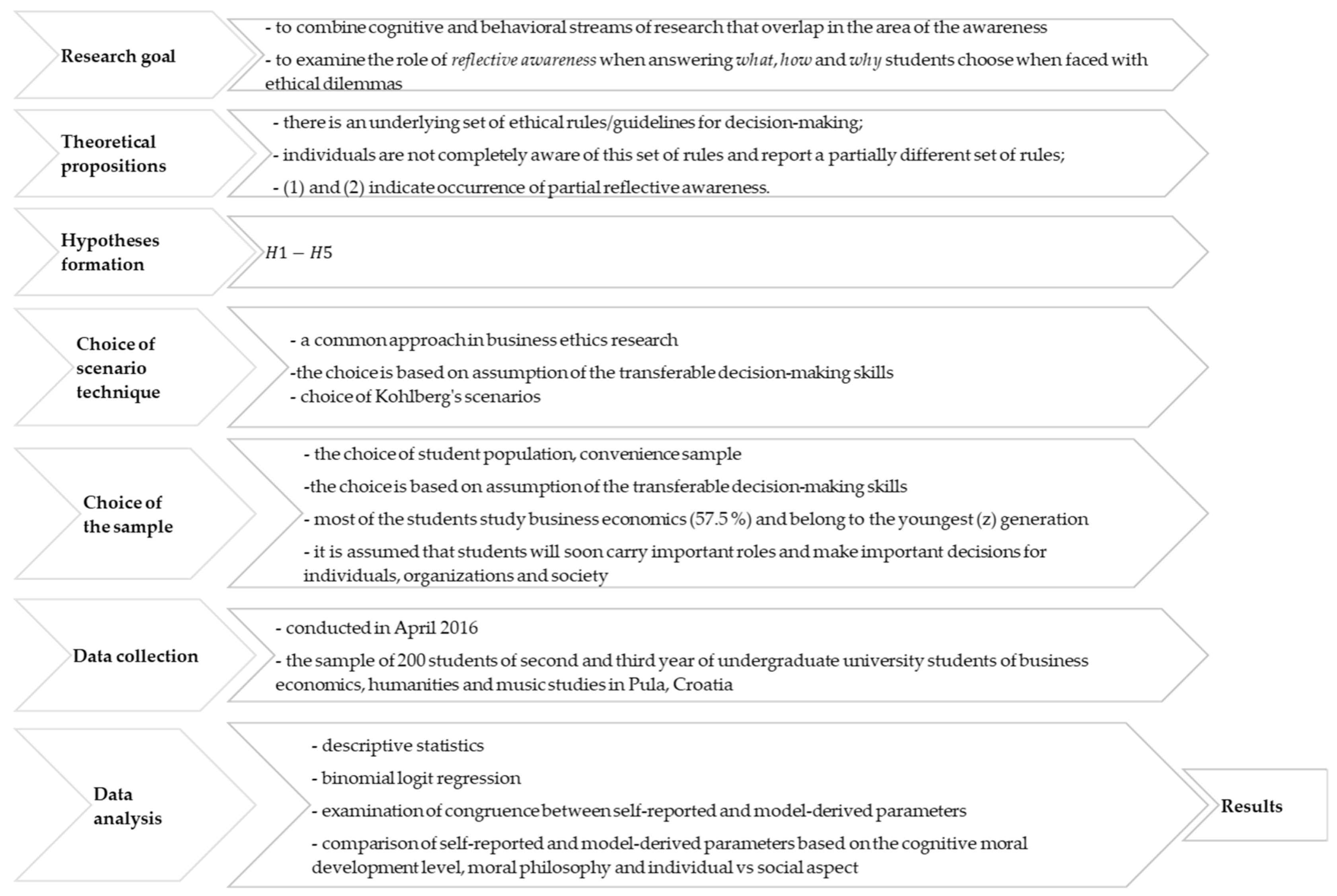

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Goal and Hypotheses

- there is an underlying set of ethical rules/guidelines for decision-making;

- individuals are not completely aware of this set of rules and report a partially different set of rules;

- (1) and (2) indicate occurrence of partial reflective awareness.

- the ambiguity and complexity of the ethical dilemmas;

- the arousal (implied by the characteristics of the ethical dilemmas);

- the level of moral cognitive development;

- the moral philosophy.

2.2. The Choice of Scenario Technique and the Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. What Did the Respondents Choose?

3.2. How Did the Respondents Choose?

3.3. Are the Respondents Aware of Their Own Ethical Decision-Making Guidelines?

3.4. Why Did the Respondents Make a Certain Choice?

- there is an underlying set of rules/guidelines for decision-making;

- individuals are not completely aware of this set of rules and report a partially different set of rules;

- (1) and (2) indicate occurrence of bounded rationality and partial reflective awareness (or bounded ethical metacognition).

- reflective awareness diminishes as ambiguity and complexity of the scenarios increase;

- partial reflective awareness of own level of moral cognitive development decreases with the characteristics and arousal intensity;

- reflective awareness about own moral philosophy diminishes with the characteristics and arousal intensity.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Heinz | In Europe a woman was near death from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost to make. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying, and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said, “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So Heinz got desperate and began to think about breaking into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should Heinz steal the drug? | |

| Name | Question | Response |

| Choice | Heinz should take the following action. | 1 = Should steal. 2 = Cannot decide 3 = Should not steal. 99 = Missing |

| HNZ1 | Whether a community’s laws are going to be upheld. | 1 = Great importance in making a decision. 2 = Much importance in making a decision. 3 = Some importance in making a decision. 4 = Little importance in making a decision. 5 = Not important or does not make sense 99 = Missing. |

| HNZ2 | Isn’t it only natural for a loving husband to care so much for his wife that he’d steal? | |

| HNZ3 | Is Heinz willing to risk getting shot as a burglar or going to jail for the chance that stealing the drug might help? | |

| HNZ4 | Whether Heinz is a professional wrestler, or has considerable influence with professional wrestlers. | |

| HNZ5 | Whether Heinz is stealing for himself or doing this solely to help someone else. | |

| HNZ6 | Whether the druggist’s rights to his invention have to be respected. | |

| HNZ7 | Whether the essence of living is more encompassing than the termination of dying, socially and individually | |

| HNZ8 | What values are going to be the basis for governing how people act towards each other. | |

| HNZ9 | Whether the druggist is going to be allowed to hide behind a worthless law which only protects the rich anyhow. | |

| HNZ10 | Whether the law in this case is getting in the way of the most basic claim of any member of society | |

| HNZ11 | Whether the druggist deserves to be robbed for being so greedy and cruel. | |

| HNZ12 | Would stealing in such a case bring about more total good for the whole society or not. | |

| Prisoner | A man had been sentenced to prison for 10 years. After one year, however, he escaped from the prison, moved to a new area of the country, and took on the name of Thompson. For eight years he worked hard, and gradually he saved enough money to buy his own business. He was fair to his customers, gave his employees top wages, and gave most of his own profits to charity. Then one day, Mrs. Jones, an old neighbor, recognized him as the man who had escaped from prison eight years before, and whom the police had been looking for. Should Mrs. Jones report Mr. Thompson to the police and have him sent back to prison? | |

| Name | Question | Response |

| Prisoner | Mrs. Jones should take the following action | 1 = Should report him. 2 = Cannot decide 3 = Should not report him. 99 = Missing |

| PRS1 | Hasn’t Mr. Thompson been good enough for such a long time to prove he isn’t a bad person? | 1 = Great importance in making a decision. 2 = Much importance in making a decision. 3 = Some importance in making a decision. 4 = Little importance in making a decision. 5 = Not important or does not make sense 99 = Missing. |

| PRS2 | Every time someone escapes punishment for a crime, doesn’t that just encourage more crime? | |

| PRS3 | Wouldn’t we be better off without prisons and the oppression of our legal system | |

| PRS4 | Has Mr. Thompson really paid his debt to society? | |

| PRS5 | Would society be failing what Mr. Thompson should fairly expect? | |

| PRS6 | What benefits would prisons be apart from society, especially for a charitable man? | |

| PRS7 | How could anyone be so cruel and heartless as to send Mr. Thompson to prison? | |

| PRS8 | Would it be fair to all the prisoners who had to serve out their full sentences if Mr. Thompson was let off? | |

| PRS9 | Was Mrs. Jones a good friend of Mr. Thompson? | |

| PRS10 | Wouldn’t it be a citizen’s duty to report an escaped criminal, regardless of the circumstances? | |

| PRS11 | How could the will of the people and the public good best be served? | |

| PRS12 | Would going to prison do any good for Mr. Thompson or protect anybody? | |

| Newspaper | Fred, a senior in high school, wanted to publish a mimeographed newspaper for students so that he could express many of his opinions. He wanted to speak out against the use of the military in international disputes and to speak out against some of the school’s rules, like the rule forbidding boys to wear long hair. When Fred started his newspaper, he asked his principal for permission. The principal said it would be all right if before every publication Fred would turn in all his articles for the principal’s approval. Fred agreed and turned in several articles for approval. The principal approved all of them and Fred published two issues of the paper in the next two weeks. But the principal had not expected that Fred’s newspaper would receive so much attention. Students were so excited by the paper that they began to organize protests against the hair regulation and other school rules. Angry parents objected to Fred’s opinions. They phoned the principal telling him that the newspaper was unpatriotic and should not be published. As a result of the rising excitement, the principal ordered Fred to stop publishing. He gave a reason that Fred’s activities were disruptive to the operation of the school. Should the principal stop the newspaper? | |

| Name | Question | Response |

| Newspaper | Should the Principal stop the newspaper? | 1 = Should stop it 2 = Cannot decide 3 = Should not stop it 99 = Missing |

| NWP1 | Is the principal more responsible to students or to parents? | 1 = Great importance in making a decision. 2 = Much importance in making a decision. 3 = Some importance in making a decision. 4 = Little importance in making a decision. 5 = Not important or does not make sense 99 = Missing. |

| NWP2 | Did the principal give his word that the newspaper could be published for a long time, or did he just promise to approve the newspaper one issue at a time? | |

| NWP3 | Would the students start protesting even more if the principal stopped the newspaper? | |

| NWP4 | When the welfare of the school is threatened, does the principal have the right to give orders to students? | |

| NWP5 | Does the principal have the freedom of speech to say “no” in this case? | |

| NWP6 | If the principal stopped the newspaper would he be preventing full discussion of important problems? | |

| NWP7 | Whether the principal’s order would make Fred lose faith in the principal. | |

| NWP8 | Whether Fred was really loyal to his school and patriotic to his country. | |

| NWP9 | What effect would stopping the paper have on the student’s education in critical thinking and judgment? | |

| NWP10 | Whether Fred was in any way violating the rights of others in publishing his own opinions. | |

| NWP11 | Whether the principal should be influenced by some angry parents when it is the principal that knows best what is going on in the school. | |

| NWP12 | Whether Fred was using the newspaper to stir up hatred and discontent. | |

| Choose the question number for the four most important statements used in your decision-making: First most important statement (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) Second most important statement (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) Third most important statement (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) Fourth most important statement (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) (11) (12) | ||

References

- DeTienne, K.B.; Ellertson, C.F.; Ingerson, M.C.; Dudley, W.R. Moral Development in Business Ethics: An Examination and Critique. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S. Ethical decision-making theory: An integrated approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherré, B.; Laarraf, Z.; Peterson, J. Why is it difficult to be virtuous in business ethics? Hum. Syst. Manag. 2019, 38, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, L.K.; Weaver, G.R.; Reynolds, S.J. Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 951–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.D.; McGee, Z.A. Agenda setting and bounded rationality. In The Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Political Science; Oxford Handbooks Online; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D. Economic rationality and a moral science of business ethics. Philos. Manag. 2016, 15, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.G.; Webb, D.A.; Chappell, S.; Gentile, M.C. Giving Voice to Values: A new perspective on ethics in globalised organisational environments. In Ethical Models and Applications of Globalization: Cultural, Socio-Political and Economic Perspectives; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 160–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Gino, F. Behavioral ethics: Toward a deeper understanding of moral judgment and dishonesty. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djawadi, B.M.; Fahr, R. “… and they are really lying”: Clean evidence on the pervasiveness of cheating in professional contexts from a field experiment. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 48, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Sezer, O. Bounded awareness: Implications for ethical decision making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 136, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.C.; Richardson, W.D. Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. J. Bus. Ethics 1994, 13, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, K.; Park, Y.-H.; Singh, N. Research note and review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: Boundary conditions and extensions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loe, T.W.; Ferrell, L.; Mansfield, P. A review of empirical studies assessing ethical decision making in business. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 25, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, J.L. A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 221–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.A.; Longenecker, J.G.; McKinney, J.A.; Moore, C.W. Ethical attitudes of students and business professionals: A study of moral reasoning. J. Bus. Ethics 1988, 7, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, T.L.; Conroy, S.J. Have ethical attitudes changed? An intertemporal comparison of the ethical perceptions of college students in 1985 and 2001. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, M.J.; Butterfield, K.D. A Review of the Empirical Decision-Making Literature. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 29, 375–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokić, A. Moral reasoning among Croatian students of different academic orientations. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2017, 2, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cagle, J.A.B.; Baucus, M.S. Case studies of ethics scandals: Effects on ethical perceptions of finance students. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, V.N. Managerial decision-making on moral issues and the effects of teaching ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 78, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J.R. Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, D.; Bazerman, M.H.; Banaji, M.R. Bounded ethicality as a psychological barrier to recognizing conflicts of interest. In Conflicts of Interest: Challenges and Solutions in Business, Law, Medicine, and Public Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 74–95. [Google Scholar]

- Fwu, B.J.; Chen, S.W.; Wei, C.F.; Wang, H.H. I believe; therefore, I work harder: The significance of reflective thinking on effort-making in academic failure in a Confucian-heritage cultural context. Think. Skills Creat. 2018, 30, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Martí, A.; Puig, M.S.; Ruiz-Bueno, A.; Regós, R.A. Implementation and assessment of an experiment in reflective thinking to enrich higher education students’ learning through mediated narratives. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 29, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlberg, L. The Development of Modes of Moral Thinking in the Years Ten to Sixteen. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg, L. Essays on Moral Development/The Psychology of Moral Development; Harper & Row: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, S.K.S. Stages of Moral Development/S. McLeod. 2013. Developmental Psychology. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/kohlberg.html (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Gilligan, C. In a different voice: Women’s conceptions of self and of morality. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1977, 47, 481–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, J.M.; Harvey, R.J. An analysis of the factor structure of Jones’ moral intensity construct. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudine, A.; Thorne, L. Emotion and ethical decision-making in organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 31, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rest, J.R.; Narváez, D. (Eds.) Moral Development in the Professions: Psychology and Applied Ethics; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kligyte, V.; Connelly, S.; Thiel, C.; Devenport, L. The influence of anger, fear, and emotion regulation on ethical decision making. Hum. Perform. 2013, 26, 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, T.L. A review of Donaldson and Dunfee’s ties that bind: A social contracts approach to business ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.S. Thinking about thinking: Beyond decision-making rationalism and the emergence of behavioral ethics. Public Integr. 2018, 20 (Suppl. 1), S89–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigerenzer, G. Moral satisficing: Rethinking moral behavior as bounded rationality. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2010, 2, 528–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 108, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Rose, J.M.; Greene, W.H. Applied Choice Analysis: A Primer; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer, C.F.; Loewenstein, G.; Rabin, M. (Eds.) Advances in Behavioral Economics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, D.; Bazerman, M.H. Bounded awareness: What you fail to see can hurt you. Mind Soc. 2007, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, M.R.; Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Bazerman, M.H. Bounded ethicality and ethical fading in negotiations: Understanding unintended unethical behavior. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 33, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaji, M.R.; Greenwald, A.G. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chugh, D.; Kern, M.C. A dynamic and cyclical model of bounded ethicality. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, F.J. Ethics and behavioural theory: How do professionals assess their mental models? J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Caruso, E.M.; Bazerman, M.H. When perspective taking increases taking: Reactive egoism in social interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, F.; Norton, M.I.; Weber, R.A. Motivated Bayesians: Feeling moral while acting egoistically. J. Econ. Perspect. 2016, 30, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L. Academic dishonesty: Are more students cheating? Bus. Commun. Q. 2011, 74, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.C.; Chugh, D. Bounded ethicality: The perils of loss framing. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gino, F.; Shu, L.L.; Bazerman, M.H. Nameless+ harmless= blameless: When seemingly irrelevant factors influence judgment of (un) ethical behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2010, 111, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, D.A.; Loewenstein, G. Helping a victim or helping the victim: Altruism and identifiability. J. Risk Uncertain. 2003, 26, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, F.; Bazerman, M.H. When misconduct goes unnoticed: The acceptability of gradual erosion in others’ unethical behavior. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, F.; Pierce, L. Dishonesty in the name of equity. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. How We Think; Prometheus Books: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Fornes, G.; Monfort, A.; Ilie, C.; Koo, C.K.T.; Cardoza, G. Ethics, Responsibility, and Sustainability in MBAs. Understanding the Motivations for the Incorporation of ERS in Less Traditional Markets. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Teaching for a better world. Sustainability and sustainable development goals in the construction of a change-maker university. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottardello, D.; Pàmies, M.M. Business school professors’ perception of ethics in education in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormo-Carbó, G.; Seguí-Mas, E.; Oltra, V. Business ethics as a sustainability challenge: Higher education implications. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Martínez-Cañas, R.; Jiménez-Estévez, P. Are Corporate Social Responsibility Courses Effective? A Longitudinal and Gender-Based Analysis in Undergraduate Students. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Barreto, I.M.; Merino-Tejedor, E.; Sánchez-Santamaría, J. University Students’ Perspectives on Reflective Learning: Psychometric Properties of the Eight-Cultural-Forces Scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zach, S.; Ophir, M. Using Simulation to Develop Divergent and Reflective Thinking in Teacher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassachs, M.; Cañabate, D.; Serra, T.; Colomer, J. Interdisciplinary Cooperative Educational Approaches to Foster Knowledge and Competences for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquin, J.J.B.; Biana, H.T. Sustainability science is ethics: Bridging the philosophical gap between science and policy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J.; Bjorklund, F. Social intuitionists answer six questions about morality. In Moral Psychology; Sinnott-Armstrong, W., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kostelic, K. Guessing the Game: An Individual’s Awareness and Assessment of a Game’s Existence. Games 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heinz Scenario | Prisoner Scenario | Newspaper Scenario | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | |||

| Missing | 6 | 3.0 | Missing | 4 | 2.0 | Missing | 9 | 4.5 |

| Should steal | 92 | 46.0 | Should report him | 67 | 33.5 | Should stop it | 36 | 18.0 |

| Cannot decide | 43 | 21.5 | Cannot decide | 75 | 37.5 | Cannot decide | 41 | 20.5 |

| Should not steal | 59 | 29.5 | Should not report him | 54 | 27.0 | Should not stop it | 114 | 57.0 |

| Total | 200 | 100.0 | Total | 200 | 100.0 | Total | 200 | 100.0 |

| Heinz Scenario | Coefficient | p-Value | Prisoner Scenario | Coefficient | p-Value | Newspaper Scenario | Coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| const | 0.6177 | 0.7244 | const | 4.9664 | 0.0198 ** | const | 3.2298 | 0.001 *** |

| HNZ1 | −0.6178 | 0.0059 *** | PRS1 | −2.306 | <0.0001 *** | NWP6 | −0.4854 | 0.0113 ** |

| HNZ2 | 1.1198 | 0.0001 *** | PRS2 | 1.4035 | 0.0002 *** | NWP9 | −0.678 | 0.0005 *** |

| HNZ6 | −0.6171 | 0.006 *** | PRS12 | −0.5471 | 0.0665 * | |||

| HNZ8 | −0.6786 | 0.0057 *** | ||||||

| HNZ9 | −0.3975 | 0.0337 ** | ||||||

| HNZ12 | 0.7531 | 0.0003 *** | ||||||

| Mean dependent var | 0.6138 | 0.5537 | 0.2416 | |||||

| McFadden R-squared | 0.3793 | 0.6267 | 0.1463 | |||||

| S.D. dependent var | 0.4886 | 0.4992 | 0.4295 | |||||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.3069 | 0.5786 | 0.1099 | |||||

| Log-likelihood | −60.0339 | −31.052 | −70.336 | |||||

| Schwarz criterion | 154.905 | 81.2874 | 155.684 | |||||

| Akaike criterion | 134.0679 | 70.1043 | 146.672 | |||||

| Hannan-Quinn | 142.5347 | 74.6462 | 150.333 | |||||

| Number of cases ‘correctly predicted’ | 115 (79.3%) | 107 (88.4%) | 112 (75.2%) | |||||

| f(beta’x) at mean of independent vars | 0.489 | 0.499 | 0.43 | |||||

| LRT: Chi-square (12) | 73.3682 [0.0000] | 104.238 [0.0000] | 24.101 [0.0000] | |||||

| Mean (Average Relevance) | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

| Heinz most important: HNZ2 | 4.39 | 0.98 |

| Heinz second most important: HNZ3 | 4.13 | 1.061 |

| Heinz third most important: HNZ10 | 3.69 | 1.09 |

| Heinz fourth most important: HNZ12 | 3.57 | 1.376 |

| Prisoner most important: PRS1 | 1.89 | 0.998 |

| Prisoner second most important: PRS4 | 2.78 | 1.498 |

| Prisoner third most important: PRS8 | 2.55 | 1.266 |

| Prisoner fourth most important: PRS10 | 2.82 | 1.44 |

| Newspaper most important: NWP1 | 2.52 | 0.857 |

| Newspaper second most important: NWP6 | 3.61 | 1.131 |

| Newspaper third most important: NWP9 | 2.77 | 1.399 |

| Newspaper fourth most important: NWP10 | 3.85 | 1.058 |

| Scenario | Properties | Statements | Median/Frequency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heinz scenario | Model-derived | HNZ1 | HNZ2 | HNZ6 | HNZ8 | HNZ9 | HNZ12 | |

| Kohlberg’s categories | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5a | 5a | 4.5 | |

| Moral philosophy | Moral Rights | Moral Rights (Values) | Moral Rights | Moral Rights (Values) | Justice | Utilitarianism | Moral Rights (66.66%), Justice (16.67%), Utilitarianism (16.67%) | |

| Individual/social aspect of moral philosophy | Social | Individual | Individual | Social | Social | Social | Social (66.67%), Individual (33.33%) | |

| Self-reported | HNZ2 | HNZ3 | HNZ10 | HNZ12 | ||||

| Kohlberg’s categories | 3 | 2 | 5a | 5a | 4 | |||

| Moral philosophy | Moral Rights (Values) | Justice (Values) | Moral Rights | Utilitarianism | Moral Rights (50%), Justice (25%), Utilitarianism (25%) | |||

| Individual/social aspect of moral philosophy | Individual | Individual | Social | Social | Individual (50%), Social (50%) | |||

| Prisoner scenario | Model-derived | PRS1 | PRS2 | PRS12 | ||||

| Kohlberg’s categories | 3 | 4 | 5a | 4 | ||||

| Moral philosophy | Justice | Utilitarianism | Utilitarianism | Utilitarianism (66.67%), Justice (33.33%) | ||||

| Individual/social aspect of moral philosophy | Individual | Social | Social | Social (66.67%), Individual (33.33%) | ||||

| Self-reported | PRS1 | PRS4 | PRS8 | PRS10 | ||||

| Kohlberg’s categories | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Moral philosophy | Justice | Justice | Moral Rights | Justice (Value) | Justice (75%), Moral Rights (25%) | |||

| Individual/social aspect of moral philosophy | Individual | Individual | Social | Social | Individual (50%), Social (50%) | |||

| Newspaper scenario | Model-derived | NWP6 | NWP9 | |||||

| Kohlberg’s categories | 5a | 5b | 5 | |||||

| Moral philosophy | Moral Rights | Utilitarianism | Moral Rights (50%), Utilitarianism (50%) | |||||

| Individual/social aspect of moral philosophy | Social | Social | Social (100%) | |||||

| Self-reported | NWP1 | NWP6 | NWP9 | NWP10 | ||||

| Kohlberg’s categories | 4 | 5a | 5b | 5a | 5 | |||

| Moral philosophy | Utilitarianism | Moral Rights | Utilitarianism | Moral Rights | Moral Rights (50%), Utilitarianism (50%) | |||

| Individual/social aspect of moral philosophy | Social | Social | Social | Social | Social (100%) | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonan Božac, M.; Kostelić, K.; Paulišić, M.; Smith, C.G. Business Ethics Decision-Making: Examining Partial Reflective Awareness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052635

Gonan Božac M, Kostelić K, Paulišić M, Smith CG. Business Ethics Decision-Making: Examining Partial Reflective Awareness. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052635

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonan Božac, Marli, Katarina Kostelić, Morena Paulišić, and Charles G. Smith. 2021. "Business Ethics Decision-Making: Examining Partial Reflective Awareness" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052635

APA StyleGonan Božac, M., Kostelić, K., Paulišić, M., & Smith, C. G. (2021). Business Ethics Decision-Making: Examining Partial Reflective Awareness. Sustainability, 13(5), 2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052635