The Antecedents and Consequences of Rapport between Customers and Salespersons in the Tourism Industry

Abstract

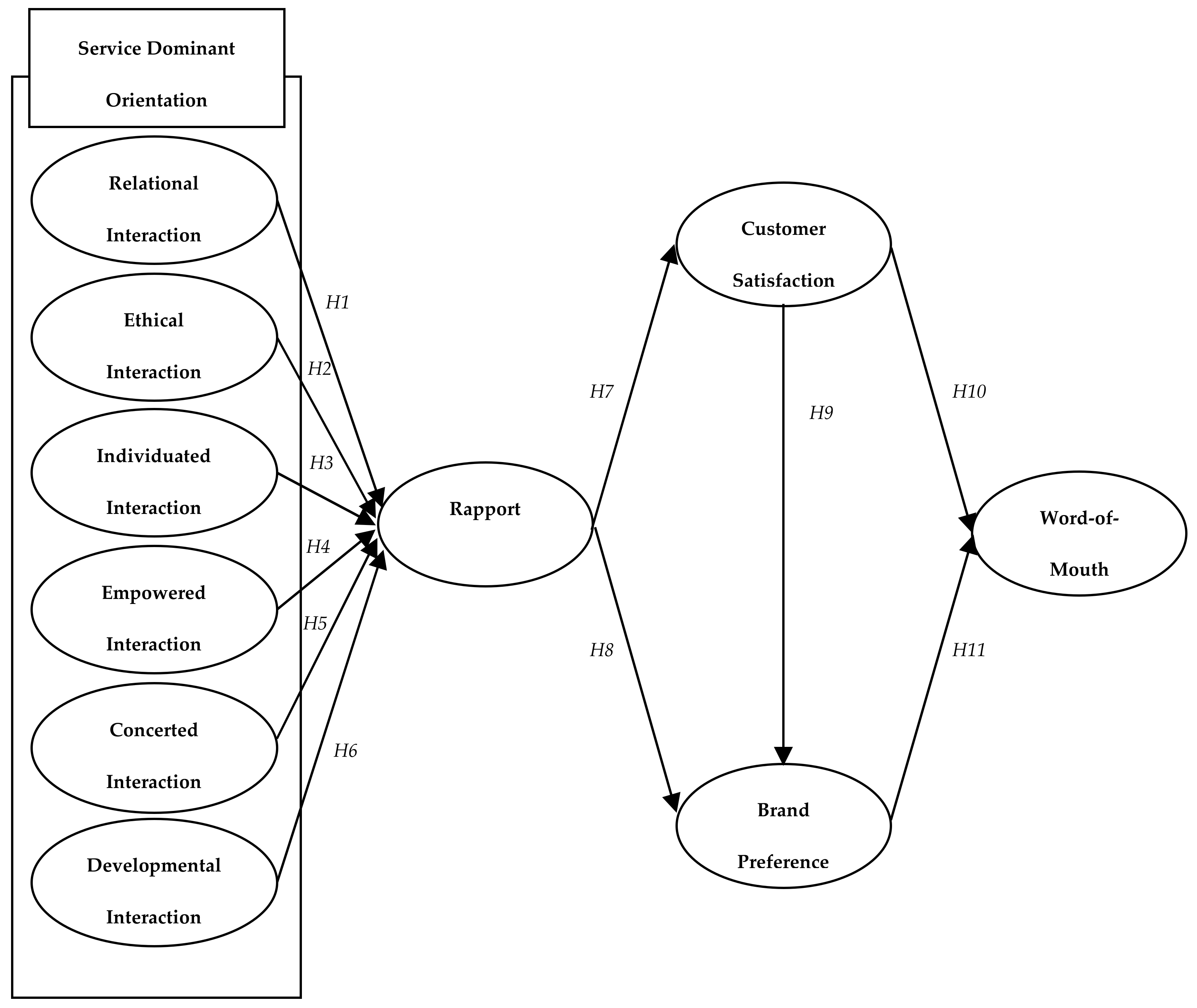

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Rapport

2.2. Service-Dominant Orientation

2.3. Customer Satisfaction

2.4. Brand Preference

2.5. Word-of-Mouth Communications

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Tourism Academy. Annual Report of China Outbound Tourism Development 2014; China Tourism Academy: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.T.; Chen, C.Y. Shopping satisfaction at airport duty-free stores: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2013, 22, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Korea Herald. Duty-free Business Becomes Cash Cow Only for Bigger Players 2019. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20190506000105 (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Asia Economic. Highest Amount of Sales in Duty Free Shops Despite Less Spending of Inbound Tourists 2019. Available online: https://www.asiae.co.kr/article/2019061811110688568 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Park, J.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Moon, W.C. Investigating the effects of sales promotions on customer behavioral intentions at duty-free shops: An Incheon International Airport case study. J. Airl. Airpt. Manag. 2013, 3, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedenbach, G.; Bengtsson, M.; Wincent, J. Brand equity in the professional service context: Analyzing the impact of employee role behavior and customer–employee rapport. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.S.; Davis, L.; Skinner, L. Rapport management during the exploration phase of the salesperson–customer relationship. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2006, 26, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A.; Brown, S.W. Contact employees: Relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Customer orientation: Effects on customer service perceptions and outcome behaviors. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A.; Roter, D.L.; Blanch, D.C.; Frankel, R.M. Observer-rated rapport in interactions between medical students and standardized patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 76, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremler, D.D.; Gwinner, K.P. Customer-employee rapport in service relationships. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpen, I.O.; Bove, L.L.; Lukas, B.A.; Zyphur, M.J. Service-dominant orientation: Measurement and impact on performance outcomes. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solnet, D.; Kandampully, J. How some service firms have become part of “service excellence” folklore. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Groth, M.; Paul, M.; Gremler, D.D. Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickle-Degnen, L.; Rosenthal, R. Group rapport and nonverbal behavior. In Review of Personality and Social Psychology; C. Hendrick, C., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987; Volume 9, pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Dell Sherry, A. Relational Communication and Organizational Customer Loyalty. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- LaBahn, D.W. Advertiser perceptions of fair compensation, confidentiality, and rapport. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Catt, S.; Miller, D.; Schallenkamp, K. You are the key: Communicate for learning effectiveness. Education 2007, 127, 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt, T.; Brady, M.K. Rethinking service recovery strategies: The effect of rapport on consumer responses to service failure. J. Serv. Res. 2003, 6, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surprenant, C.F.; Solomon, M.R. Predictability and personalization in the service encounter. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, J. Small talk: Social functions. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 2003, 36, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremler, D.D.; Gwinner, K.P. Rapport-building behaviors used by retail employees. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, D.A.; Plank, R.E.; Minton, A.P. Industrial buyers’ assessments of sales behaviors. J. Mark. Manag. 1997, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lakin, J.L.; Chartrand, T.L. Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 14, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Ok, C.; Gwinner, K.P. The antecedent role of customer-to-employee relationships in the development of customer-to-firm relationships. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartline, M.D.; Ferrell, O.C. The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.T.; Hu, H.H. The effect of relational benefits on perceived value in relation to customer loyalty: An empirical study in the Australian coffee outlets industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D. Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. J. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpen, I.O.; Bove, L.L.; Lukas, B.A. Linking service-dominant logic and strategic business practice: A conceptual model of a service-dominant orientation. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Evans, K.R.; Zou, S. The effects of customer participation in co-created service recovery. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L.; Tanniru, M. Service, value networks and learning. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Akaka, M.A. Service-dominant logic as a foundation for service science: Clarifications. Serv. Sci. 2009, 1, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macintosh, G. Customer orientation, relationship quality, and relational benefits to the firm. J. Serv. Mark. 2007, 21, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Lambe, C.J. Marketing’s contribution to business strategy: Market orientation, relationship marketing and resource-advantage theory. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2000, 2, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavondo, F.T.; Rodrigo, E.M. The effect of relationship dimensions on interpersonal and interorganizational commitment in organizations conducting business between Australia and China. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Bowen, D.E. Winning the service game. In Handbook of Service Science; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 31–59. [Google Scholar]

- Olkkonen, R.; Tikkanen, H.; Alajoutsijärvi, K. The role of communication in business relationships and networks. Manag. Decis. 2000, 38, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, C. RECOVSAT: An instrument to measure satisfaction with transaction-specific service recovery. J. Serv. Res. 1999, 1, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremler, D.D.; Gwinner, K.P.; Brown, S.W. Generating positive word-of-mouth communication through customer-employee relationships. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2001, 12, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, B.; Dwyer, L.; Prideaux, B. An evaluation of unethical business practices in Australia’s China inbound tourism market. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 8, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geyskens, I.; Steenkamp, J.B.E.; Kumar, N. Generalizations about trust in marketing channel relationships using meta-analysis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1998, 15, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Tourism Export Council. “Rogue” Operator Problem Tackled at Gold Coast Workshop. 2005. Available online: http://www.atec.net.au/MediaRelease_Rogue_operator_problem_tackled_at_Gold_Coast_Workshop.htm (accessed on 23 May 2016).

- Han, H.; Yu, J.; Lee, K.S.; Baek, H. Impact of corporate social responsibilities on customer responses and brand choices. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Koo, B.; Hyun, S.S. Image congruity as a tool for traveler retention: A comparative analysis on South Korean full-service and low-cost airlines. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sisodia, R.S.; Sharma, A. The antecedents and consequences of customer-centric marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gremler, D.D.; Rinaldo, S.B.; Kelley, S.W. Rapport-Building Strategies Used by Service Employees: A Critical Incident Study; Conference Proceedings; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002; p. 73. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Tetreault, M.S. The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.L.; Arnould, E.J.; Deibler, S.L. Consumers’ emotional responses to service encounters: The influence of the service provider. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1995, 6, 34–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R.S.; Hyman, M.R.; McQuitty, S. Exchange-specific self-disclosure, social self-disclosure, and personal selling. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2001, 9, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, R.; Ramirez, R. From value chain to value constellation: Designing interactive strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaignanam, K.; Varadarajan, R. Customers as co-producers. In The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate, and Directions; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2006; pp. 166–179. [Google Scholar]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, J.; Hyun, S.S. Effective communication styles for the customer-oriented service employee: Inducing dedicational behaviors in luxury restaurant patrons. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, D.J.; Mentzer, J.T. Striving for Integrated Value Chain Management Given a Service-Dominant: The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate, and Directions; ME Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan, S.; Hess, R. Dimensions and levels of trust: Implications for commitment to a relationship. Mark. Lett. 1997, 8, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, K.S.; Chua, B.L.; Lee, S. Contribution of airline F&B to passenger loyalty enhancement in the full-service airline industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 380–395. [Google Scholar]

- Gremler, D.D.; Brown, S.W. January, Service Loyalty: Antecedents, Components, and Outcomes; Conference Proceedings; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur, W.; Khan, A.N.; Ali, A.; Usman, M. Investigating the effect of employee empathy on service loyalty: The mediating role of trust in and satisfaction with a service employee. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2020, 19, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, T.M.; Niazi, M.R.; Rizvi, R.; Khan, I. The relationship between brand trust, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty (evidence from automobile sector of Pakistan). Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2012, 4, 489–502. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Barry, T.E.; Dacin, P.A.; Gunst, R.F. Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.L.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, S.; Han, H. The role of brand personality, self-congruity, and sensory experience in elucidating sky lounge users’ behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Building Customer-Based Brand Equity: A Blueprint for Creating Strong Brands; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Measuring brand equity across products and markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 50, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, D.A.; Prevel Katsanis, L. Understanding brand equity for successful brand extension. J. Consum. Mark. 1995, 12, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gensch, D.H. Empirically testing a disaggregate choice model for segments. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.H.; Lattin, J.M. Development and testing of a model of consideration set composition. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Moschis, G.P.; Lee, E. Life events and brand preference changes. J. Consum. Behav. 2003, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Hyun, S.S. First-class airline travellers’ perception of luxury goods and its effect on loyalty formation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Relationship marketing of services—Growing interest, emerging perspectives. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.E.; Beatty, S.E. Customer benefits and company consequences of customer-salesperson relationships in retailing. J. Retail. 1999, 75, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Baker, M.A. How the employee looks and looks at you: Building customer–employee rapport. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Grisaffe, D.B. Employee commitment to the organization and customer reactions: Mapping the linkages. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Silkes, C. Tourist shopping style preferences. J. Vacat. Mark. 2014, 20, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.K.; Lee, T.J. Tourists’ impulse buying behavior at duty free shops: The moderating effects of time pressure and shopping involvement. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M. Customer satisfaction and its consequences on customer behaviour revisited: The impact of different levels of satisfaction on word-of-mouth, feedback to the supplier and loyalty. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1998, 9, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.A. Product/consumption-based affective responses and postpurchase processes. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 4, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Jung, H.; Kim, W. The role of wellness spa tourism performance in building destination loyalty: The case of Thailand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Wong, K.H.; Fang, P.W. The effects of customer relationship management relational information processes on customer-based performance. Decis. Support. Syst. 2014, 66, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Wang, Y.C. The influences of electronic word-of-mouth message appeal and message source credibility on brand attitude. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2011, 23, 448–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Walsh, G.; Walsh, G. Electronic word-of-mouth: Motives for and consequences of reading customer articulations on the Internet. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 8, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M.S. The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matos, C.A.; Rossi, C.A.V. Word-of-mouth communications in marketing: A meta-analytic review of the antecedents and moderators. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, R.V.; De Valck, K.; Wojnicki, A.C.; Wilner, S.J. Networked narratives: Understanding word-of-mouth marketing in online communities. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Corfman, K.P. Quality and value in the consumption experience: Phaedrus rides again. In Perceived Quality; Jacoby, J., Olson, J., Eds.; Lexington: Lexington, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Wong, A. Exploring the influence of product conspicuousness and social compliance on purchasing motives of young Chinese consumers for foreign brands. J. Consum. Behav. 2008, 7, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ok, C.; Canter, D.D. Contingency variables for customer share of visits to full-service restaurant. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiningham, T.L.; Perkins-Munn, T.; Aksoy, L.; Estrin, D. Does customer satisfaction lead to profitability? The mediating role of share of wallet. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2005, 15, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Brand Preference and Its Impacts on Customer Share of Visits and Word-of-Mouth Intention: An Empirical Study in the Full-Service Restaurant Segment. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.G.; Han, J.S.; Lee, E. Effects of relationship marketing on repeat purchase and word of mouth. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bloemer, J.M. The impact of value congruence on consumer-service brand relationships. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 11, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Magnini, V.P.; Singal, M. The effects of customers’ perceptions of brand personality in casual theme restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ok, C. Customer orientation of service employees and rapport: Influences on service-outcome variables in full-service restaurants. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ok, C.; Canter, D.D. Value-driven customer share of visits. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granello, D.H.; Wheaton, J.E. Online data collection: Strategies for research. J. Couns. Dev. 2004, 82, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, W.G. Business Research Methods; Thomson/South Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Duty Free Shops Association. Korea Tourism Statistics. Available online: http://www.kdfa.or.kr/ko/dutyfree/search.php (accessed on 4 July 2019).

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C., Jr.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Wen, B.; Ouyang, Z. Developing relationship quality in economy hotels: The role of perceived justice, service quality, and commercial friendship. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 1027–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Iqbal, N.; Javed, K.; Hamad, N. Impact of organizational commitment and employee performance on the employee satisfaction. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2014, 1, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Han, H.; Kim, S. How can employees engage customers? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; Laverie, D.A.; McLane, C. Using job satisfaction and pride as internal satisfaction. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wen, C.; George, B.; Prybutok, V.R. Consumer heterogeneity, perceived value, and repurchase decision-making in online shopping: The role of gender, age, and shopping motives. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2016, 17, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, B.; Jiménez, J.; José Martín, M. Age, gender and income: Do they really moderate online shopping behaviour? Online Inf. Rev. 2011, 35, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 285 | 43.9 |

| Female | 364 | 56.1 |

| Education level | ||

| High school diploma | 146 | 22.5 |

| Associate’s degree | 32 | 4.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 409 | 63.0 |

| Graduate degree | 62 | 9.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 99 | 15.3 |

| Married (including divorced and widow/widower) | 549 | 84.6 |

| Occupation | ||

| Company employee | 421 | 64.9 |

| Self-employed | 42 | 6.5 |

| Sales/service | 16 | 2.5 |

| Student | 9 | 1.4 |

| Civil servant | 44 | 6.8 |

| Professional | 109 | 16.8 |

| Other | 8 | 1.3 |

| Yearly household income | ||

| Less than US$16,601 | 127 | 19.6 |

| US$16,601~US$21,600 | 121 | 18.6 |

| US$21,601~US$27,770 | 152 | 23.4 |

| US$27,771~US$37,000 | 148 | 22.8 |

| More than US$37,000 | 101 | 15.6 |

| Mean age = 33.10 years old |

| Variable | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| How many times have you visited Korea including this tour? | ||

| One time | 146 | 22.5 |

| Two times | 248 | 38.2 |

| Three times | 146 | 22.5 |

| More than three times | 109 | 16.8 |

| Which duty-free shop did you visit during this visit? | ||

| Lotte duty-free shop | 371 | 57.2 |

| Silla duty-free shop | 184 | 28.4 |

| AK duty-free shop | 47 | 7.2 |

| Donghwa duty-free shop | 42 | 6.5 |

| Walkerhill duty-free shop | 5 | 0.8 |

| How many times have you visited the duty-free shop (you mentioned above) during this tour? | ||

| One time | 133 | 20.5 |

| Two times | 298 | 45.9 |

| Three times | 159 | 24.5 |

| Four times | 26 | 4.0 |

| Five times | 25 | 3.9 |

| More than five times | 8 | 1.3 |

| What is the main purpose of this tour for you? | ||

| Leisure | 579 | 89.2 |

| Business | 25 | 3.9 |

| To meet friends or relatives | 8 | 1.2 |

| Shopping | 37 | 5.7 |

| How long did you stay in Korea? | ||

| One night | 7 | 1.1 |

| Two nights | 71 | 10.9 |

| Three nights | 212 | 32.7 |

| Four nights | 191 | 29.4 |

| More than four nights | 168 | 25.9 |

| With whom did you travel? | ||

| Alone | 43 | 6.6 |

| Friend(s) | 236 | 36.4 |

| Association or Company | 33 | 5.1 |

| Family or Relatives | 337 | 51.9 |

| How much did you spend on shopping? Average = US$2780 (SD = US$6473) | ||

| Construct and Scale Items | Standardized Loading a |

|---|---|

| Service Dominant Orientation | |

| Relational interaction | |

| The salesperson made me feel at ease. | 0.842 |

| The salesperson tried to establish a mutual relation with me. | 0.799 |

| The salesperson encouraged two-way communication with me. | 0.807 |

| The salesperson showed genuine interest in engaging me. | 0.816 |

| Ethical interaction | |

| The salesperson did not try to take advantage of me. | 0.794 |

| The salesperson did not pressure me in any way. | 0.788 |

| The salesperson did not mislead me in any way. | 0.805 |

| The salesperson did not try to manipulate me. | 0.801 |

| Individuated interaction | |

| The salesperson made an effort to understand my individual needs. | 0.759 |

| The salesperson was sensitive to my individual situation. | 0.783 |

| The salesperson made an effort to find out what kind of offering is most helpful to me. | 0.770 |

| The salesperson sought to identify my personal expectations. | 0.779 |

| Empowered interaction | |

| The salesperson let me interact with him/her in my preferred way. | 0.805 |

| The salesperson encouraged me to customize my shopping experience. | 0.785 |

| The salesperson allowed me to control my shopping experience. | 0.736 |

| The salesperson invited me to share my own ideas or suggestions. | 0.776 |

| Concerted interaction | |

| The salesperson worked together seamlessly when selling products. | 0.754 |

| The salesperson acted as one unit when dealing with me. | 0.785 |

| The salesperson provided messages to me that were consistent with each other. | 0.775 |

| The salesperson ensured he/she had smooth procedures for interacting with me. | 0.798 |

| Developmental interaction | |

| The salesperson shared useful information with me. | 0.771 |

| The salesperson helped me become more knowledgeable. | 0.781 |

| The salesperson provided me with the advice I needed. | 0.806 |

| The salesperson offered me expertise that I could learn from. | 0.809 |

| Rapport | |

| I enjoyed interacting with the salesperson. | 0.831 |

| I felt warm-hearted in the relationship with the salesperson. | 0.788 |

| I was comfortable interacting with the salesperson. | 0.772 |

| I felt like there was a bond between myself and the salesperson. | 0.745 |

| I looked forward to seeing the salesperson when I shop at the duty-free shop next time. | 0.753 |

| I wanted to have a close relationship with the salesperson. | 0.791 |

| Customer satisfaction | |

| I was satisfied with this duty-free shop. | 0.823 |

| I was pleased to visit this duty-free shop. | 0.803 |

| I was delighted with this duty-free shop. | 0.859 |

| Brand preference | |

| When I want to shop, I very often consider this duty-free shop a viable choice. | 0.891 |

| This duty-free shop meets my shopping needs better than other comparable duty-free shops. | 0.869 |

| I am interested in this duty-free shop more than in other comparable duty-free shops. | 0.801 |

| Word-of-mouth | |

| I said positive things about this duty-free shop to others. | 0.822 |

| I recommended this duty-free shop to others. | 0.861 |

| I encouraged others to visit this duty-free shop. | 0.849 |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 1165.030, df = 620, χ2/df = 1.879, p < 0.001, NFI = 0.940, IFI = 0.971, CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.037 |

| No. of Items | Mean (SD) | AVE | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Relational interaction | 4 | 4.15 (0.92) | 0.666 | 0.889a | 0.733 b | 0.755 | 0.734 | 0.769 | 0.784 | 0.766 | 0.794 | 0.676 | 0.631 |

| (2) Ethical interaction | 4 | 4.07 (0.96) | 0.635 | 0.537 c | 0.874 | 0.788 | 0.799 | 0.713 | 0.785 | 0.748 | 0.750 | 0.661 | 0.626 |

| (3) Individuated interaction | 4 | 4.13 (0.89) | 0.597 | 0.570 | 0.621 | 0.856 | 0.736 | 0.732 | 0.745 | 0.728 | 0.782 | 0.694 | 0.670 |

| (4) Empowered interaction | 4 | 4.11 (0.88) | 0.602 | 0.539 | 0.638 | 0.542 | 0.858 | 0.725 | 0.705 | 0.744 | 0.801 | 0.722 | 0.672 |

| (5) Concerted interaction | 4 | 4.09 (0.94) | 0.606 | 0.591 | 0.508 | 0.536 | 0.526 | 0.860 | 0.749 | 0.743 | 0.796 | 0.733 | 0.650 |

| (6) Developmental interaction | 4 | 4.12 (0.95) | 0.627 | 0.615 | 0.616 | 0.555 | 0.497 | 0.561 | 0.871 | 0.763 | 0.738 | 0.732 | 0.682 |

| (7) Rapport | 6 | 4.07 (0.92) | 0.609 | 0.587 | 0.560 | 0.530 | 0.554 | 0.552 | 0.582 | 0.903 | 0.785 | 0.680 | 0.647 |

| (8) Customer satisfaction | 3 | 4.23 (0.95) | 0.687 | 0.630 | 0.563 | 0.612 | 0.642 | 0.634 | 0.545 | 0.616 | 0.868 | 0.709 | 0.710 |

| (9) Brand preference | 3 | 4.11 (0.88) | 0.730 | 0.457 | 0.437 | 0.482 | 0.521 | 0.537 | 0.536 | 0.462 | 0.503 | 0.890 | 0.732 |

| (10) Word-of-mouth | 3 | 4.19 (0.86) | 0.713 | 0.398 | 0.392 | 0.449 | 0.452 | 0.423 | 0.465 | 0.419 | 0.504 | 0.536 | 0.899 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hwang, J.; Lee, K.-W.; Kim, S. The Antecedents and Consequences of Rapport between Customers and Salespersons in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052783

Hwang J, Lee K-W, Kim S. The Antecedents and Consequences of Rapport between Customers and Salespersons in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052783

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Jinsoo, Kwang-Woo Lee, and Seongseop (Sam) Kim. 2021. "The Antecedents and Consequences of Rapport between Customers and Salespersons in the Tourism Industry" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052783