1. Introduction

Traveling is a natural part of people’s lives at almost any age. It can be characterized by regularity (accompanying children to school, shopping, etc.), but it can also be random (traveling on vacation, exploring new countries, etc.). An essential part of the life of most economically active individuals is also commuting to and from work. The exception is home office workers. The global situation, coupled with restrictive governments’ measures following the mitigation of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, has further expanded the home office space. This method has significant advantages; in many cases considerable saving in commuting time and cost [

1,

2]. There is also a direct saving in commuting times, potentially allowing more time to be devoted to productive activities [

3].

The prevention of travel and the reduction of mobility have generally led and still has positive effects on the environment, which are discussed by, e.g., Muhammad et al. [

4]. Their research outcomes indicate that pollution in some of the epicenters of COVID-19, such as Wuhan, Italy, Spain and the USA, has reduced up to 30%. Although home office work is likely to become a widely used mode of working in many areas even after the pandemic, we believe that labor mobility will remain an essential part of the global labor market. Workers will continue to cover smaller or larger distances with certain time and financial costs and commuting will continue to be of strategic importance in the everyday life of individuals and households.

The impetus for the elaboration of the paper was the use of positive experiences from abroad in the field of theoretical background and methodology, and thus, fill the knowledge gap in the conditions of the Slovak Republic. At the same time, our intention was to obtain and process data so that they were comparable with the results from other countries, thus increasing the possibility of cooperation and contributing to the common goal of developing modern and sustainable transport. We believe that the achieved results offer a starting point for the inclusion of Slovakia among the developed countries, which pay adequate attention to commuting and the consequences resulting from it, and last but not least, apply the results of knowledge to specific measures. The length of time for commuting is one of the key categories that play an essential role in day-to-day mobility decision-making [

5]. On the other hand, the organization of activities and the division of roles in the household significantly affects the patterns of commuting, which ultimately affects the subjective feeling of satisfaction/subjective well-being [

6,

7]. Traveling of any kind affects subjective experience in various ways. We believe that this topic is given insufficient attention in Slovakia and is not often in the public interest.

One of the determinants that affect individuals’ satisfaction with commuting is undoubtedly the travel mode. It makes a difference whether a commuter drives their own car, has to concentrate on driving and experiences stress from traffic, or travels e.g., by train and reads a book in addition to traveling. On the other hand, the commuter probably feels more comfort in their own car compared to a mean of public transport that is uncomfortable and crowded with passengers [

8,

9]. Determinants that influence commuters in choosing the travel mode can be objective (transport infrastructure, climate, area type), but also subjective (commuter preferences, financial possibilities, time allocation, etc.) [

10,

11].

We consider it positive that, according to the analysis based on the data of the 2001 and the 2011 Population and Housing census, the willingness of Slovaks to travel to and from work (daily commuting) increased [

12]. With an average of 4 h a week/34 min a day of commuting, the Slovak Republic is among the countries with the lowest time costs of commuting (similar to, e.g., Spain, Sweden and Finland) [

13]. Nevertheless, commuting forms a significant part of the day for many working Slovaks.

At the end of the last year, the Slovak government adopted the National Integrated Reform Plan entitled ‘Modern and Successful Slovakia.’ One of the priorities is a green economy, and within it, sustainable transport. The stated goal is for transport infrastructure to be developed based on a financially and environmentally sustainable long-term investment plan in order to increase the attractiveness of public transport and support non-motorized forms of transport.

In this context, examining the issue of commuting is considered to be necessary. This article has the ambition to contribute to the professional discussion, which draws attention to the review of determinants affecting the travel mode choice, which results in its impact on the subjective well-being (SWB) of the commuter. Our findings can be an inspiration for not only public policy makers to be a stimulus for creating sustainable transport that is not only comfortable for commuters, but also environmentally appropriate.

2. Knowledge Gap

In the Slovak Republic, from the 2011 Population and Housing census at the district as well as local level (NUTS 4, NUTS 5), the data are known about the distance traveled by employees traveling to work. These data present the differences related to the income category of employees, e.g., employees with higher incomes travel longer distances to work. We assume that this information will be expanded (much generalized) thanks to the ongoing census of 2021. We consider this known factual information to be relevant but insufficient with regard to current needs in connection with the creation of the concept of modern sustainable infrastructure in the 21st century. At the national level, there is still no more comprehensive analysis that takes into account not only the distance regularly traveled, but also other determinants related to job mobility (demographic, economic, psychological, social, family, environmental, etc.) and paid work (length of paid work, organization, intensity of work, etc.). We consider the wider research in this area to be the key in connection with the predominant nature of the territorial allocation of job opportunities in Slovakia, for which, in addition, shift work is typical (continuous operations). The intention of this scientific study is to contribute to filling the knowledge gap in the above areas in Slovakia, based on the use of own primary data from the questionnaire survey (continuous four-year research, 2017–2020), at the national level, and thus, provide initial more comprehensive information on patterns of behavior of commuters and report on the results associated with a retrospective view of the impact of travel mode on subjective well-being. Our conclusions cannot yet be compared with other scientific studies in Slovakia, as they have not yet been monitored in the structure and scope to which we offer them. In providing the above knowledge, this study is based on scientific approaches and methods that are standard in this research area (see Literature Review and Materials and Methods). We are aware that our results have limited possibilities of interpretation, but they offer additional space and inspiration for refinement as well as scientific research, which will allow us to better know and understand the patterns of behavior that come to work. These results can be applied in public and private sector policies, as commuting is known to affect labor productivity in the first hours of work, specific personnel management measures, compensation for transport costs and health and a way of rest and regeneration of the workforce, together with increased demands on home-management and fulfilment of parental or partner duties—stabilization of the family life. The results and conclusions of this scientific study may serve other researchers to compare the results with the Slovak economy, which can be considered post-socialist with a predominant concentration of economic activities around the capital in a small area.

3. Literature Review

Commuting is of strategic importance in everyday life of individuals and households. It links personal life and working life, enables reach and access to the labor market and can manifest gendered relationships between women and men. Accordingly, commuting is a concern at both the individual and household levels as well as for policy and planning at various levels [

14]. Basmajian [

15] presumes commuting as a “fluid experience equally blended into home life and work-place [sic] and points in between.”

In general, commuting is considered to be one of the least enjoyable activities within the time allocation of an individual [

16,

17,

18]. There are at least two types of costs that must be borne. The first is the “loss” of time caused by moving from home to workplace (with the exception of the “home office”). It is, therefore, clear that individuals face implicit costs, but they often do not even realize it immediately. The second type of costs that employed individuals have to deal with is explicit costs. These represent all expenses related to commuting and may vary, which of course depends on the distance and travel mode.

This raises the question of how commuting is compensated for. Stutzer and Frey [

19] used classical economic theory to conclude that a longer commute time and the associated additional psychological burden should either be compensated for by a more rewarding job (intrinsically or financially) or by additional welfare from a more attractive living situation (price, size, comfort etc.). Previous research provides a strong relationship between housing prices and distance to job opportunities and longer commutes are associated with higher earnings [

20]. However, in terms of reported subjective well-being, individuals with longer commute times are systematically worse off [

19].

There are many studies proving the relationship between travel and health/well-being. These studies examine individuals’ attitudes to travel in terms of time use, money use, the mode of transport and the conditions experienced during the journey. It is said by Wheatley [

21] that “commuting, as the most frequent reason for travel for economically active/working age individuals is perceived as a dissatisfaction-generating activity in general.” Many researchers report on the correlation between commute duration and the rise of stress and dissatisfaction [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] or health problems [

29,

30,

31]. The expected effect of trip duration is also confirmed by findings of the cross-border long-commute case study to Luxembourg: “The more it takes time, the less [the] commuter is satisfied” [

32].

There are other studies that have not found a negative correlation between satisfaction with life and commuting, but suggest that commuting is associated with lower satisfaction with specific aspects, including family and leisure time [

33]. Roberts et al. [

34] stated that commuting has a negative effect on psychological health, but only for women. This may be due to higher family commitments and home care. Morris et al. [

35] reported no association between commute time and life satisfaction of individuals.

According to Sweet and Kanaroglou [

36], identifying how travel and time use outcomes are linked with SWB has important implications if improving quality of life is to be a meaningful planning policy goal. “First, it provides guidance on what types of travel outcomes planners should target to improve SWB. Second, it identifies what types of time use and activity participation outcomes can improve SWB. Third, it can provide evidence on whom common existing policy actions and objectives are most likely to benefit” [

36].

Difficulty and ambiguity of the issue are reflected by, e.g., Haas and Osland [

37]; they reported that there is no unambiguous theory that provides a comprehensive picture of the relationship between commute time and subjective well-being.

However, Mokhtarian and Salomon [

38] suggested that travel may have a positive utility of its own which is not necessarily related to reaching a destination. The phenomenon of ‘taking the car out for a spin’ is one of the best examples of this. Even when travel is related to a destination (i.e., directed travel to and from work), people do not necessarily minimize their travel time or always choose the most cost-efficient mode or route (in terms of time, money and effort) to travel to certain destinations.

There has been increasing attention internationally on how mobility strategies and practices can contribute to better health (for example, see UNECE [

39] for the EU and CIHT [

40] for the UK). The focus has mostly been on reducing the impacts on physical health from traffic injuries and pollution and reversing the decline in physical activity. However, it is also acknowledged that transport systems and different forms of travel mode can have effects beyond physical health on people’s mental health and happiness. This has coincided with concern about the limits of GDP as a measure of economic performance and social progress and growing interest globally in measuring people’s well-being [

41].

A growing number of studies has investigated the relationship between the other travel characteristics (not only time use) and SWB of travel and life. Subjective well-being, as an alternative and enrichment to utility, has recently attracted significant attention from transportation researchers. SWB can be measured using objective measures (e.g., income) and subjective measures (e.g., happiness). In this way, it offers a direct measurement of individuals’ mood, emotion and cognitive judgment on travel experiences, and thus, better captures the experienced utilities of travel [

42,

43]. Measurement of the subjective measures is argued to be particularly important as only the person themselves knows how they are feeling [

44].

SWB is defined formally in the 2013 OECD Guidelines on Measuring SWB as “Good mental states, including all of the various evaluations, positive and negative, that people make of their lives, and the affective reactions of people to their experiences” [

45].

As such, SWB is a broad concept encompassing (1) self-evaluations of satisfaction with different aspects (or domains) of one’s life (e.g., satisfaction with home, family, job, health) and with life overall, referred to as ‘evaluative wellbeing,’ (2) the frequency with which one experiences different emotions, referred to as ‘experiential wellbeing’ and (3) whether individuals feel they are fulfilling their potential-referred to as ‘eudemonic wellbeing.’ The first two of these SWB dimensions are sometimes jointly referred to as ‘hedonic wellbeing,’ since they relate to pleasure and satisfaction [

26].

Several studies evaluate the relationship between travel behavior and SWB of travelers when using different modes of travel [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. For example, a recent study by Friman et al. [

52] found that “satisfaction with daily travel directly influences both experiential wellbeing and life satisfaction and that greater satisfaction with daily travel is highest for those that walk and cycle and lowest for those that use public transport.” The research results of Clark et al. [

53] also indicated that active commuting has some specific benefits. Walking is associated with improved SWB in terms of increased leisure time satisfaction and reduced strain and cycling is associated with higher self-reported health (but there is no certainty of the direction of the effect—it is possible that healthier people choose to cycle).

Martin et al. [

54] carried out a fixed effects modeling analysis of British Household Panel Survey data (1991–2008), and found walking to work and using the bus to be associated with better mental health than commuting by car. They also separately analyzed associations between commute mode and responses for the 12 different GHQ-12 symptoms (General Health Questionnaire scale involves 12 questions designed to detect symptoms of psychological distress) and found that car travel was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting ‘being constantly under strain’ and ‘being unable to concentrate’ compared to walking or cycling to work, but no significant differences for other symptoms. Mental health has been defined as a “state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stress of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” [

55]. However, there is not a full consensus on the definition of mental health. According to Manwell et al. [

56], mental health is distinct from SWB, since mental health refers to an objective state of the individual.

Based on data taken from the UKHLS covering 2009–2016, Jacob et al. [

57] found that mode switches affect both physical and mental health. When switching from a car to active travel we see an increase in physical health for women and in mental health for both genders. In contrast, both men and women who switch from active travel to a car are shown to experience a significant reduction in their physical health and health satisfaction, and a decline in their mental health when they change from active to public transport.

Other results of investigation show that the effects of travel mode choice on commuting satisfaction were only significant in the higher income group, where cycling commuters have the highest commuting satisfaction, and this is followed by worker bus, walking, rail transport and car commuters. These modes differences in commuting satisfaction were not significant in the lower income group [

58].

Overall, these results support to local and national governments around the world encouraging people to switch away from cars and toward more active modes of travel, including walking and cycling. “The aims of such schemes are twofold: (1) to improve population health by encouraging physical activity and (2) to reduce emissions and pollution levels” [

57].

However, despite the efforts of the governments and measures taken to promote the use of sustainable transport, they do not fully achieve their purpose. There are studies that point to many factors that limit commuters when choosing the travel mode and influence their behavior. Kaufmann [

59] analyzed the modal habits of the inhabitants of selected French and Swiss cities similar with the spatial structure, the quality of public transport and the amount of parking spaces available in centers. The results of his research show that “car drivers and public transport users base their ‘modal choice’ on the same criteria. The differing behavioral patterns observed between places originate from the different situations in which people find themselves. They are, thus, only marginally a reflection of different behavior in similar situations. Therefore, ‘situational’ rather than ‘cultural’ factors can best explain the different patterns of behavior.”

Zarabi et al. [

60] claimed that research in the area of travel mode choice and related travel satisfaction is dominated by the use of quantitative methods, leading to a lack of understanding of the complexity of subjective factors such as attitudes and values. Their qualitative analyses revealed that individuals do not necessarily use the most positively valued travel mode due to a lack of accessibility and competences, but also due to having preferences for other travel-related elements such as travel route.

Jamal and Newbold [

61] looked, in their research study, into the different factors that contributed to shaping each generation’s travel behavior and concluded that differences exist between generations in terms of travel behavior, and that the factors that influence each generation’s travel characteristics are either different or differ in their nature of influence (increase/decrease).

The traditional positivist approach to transport analysis was questioned by Banister [

62], who stated that “travel can no longer only be seen as a derived demand with no positive value in the activity of travel.” Travel has a substantial value, and that other value systems relating to experience, reliability and quality have important impacts on the nature of travel. That is why the priorities of the transport planning should be reoriented on shorter and slower travel which is connected with positive co-benefits for the environment (including safety), energy (and carbon), social inclusion, wellbeing (including health) and the economy.

However, this approach was already known in 1922 when the Wertraitionalirat concept was introduced by Max Weber who stated: “The use of public transport arises more from a system of values with which the person identifies than from the quality of the transport offered.” Based on this approach, De Las Heras-Rosas and Herrera [

63] analyzed postmodern values and citizens’ environmental awareness, linking these to sustainable mobility habits in 12 European countries and found variables that complement research on them. The results of their research suggest that a higher index of postmodern values implies greater environmental awareness, which would lead to a greater use of sustainable transport, although there are variables related to environmental knowledge and risk which indicate that greater environmental education and awareness is needed. It is clear that these facts have significant implications for local and national government policy concerning sustainable urban development.

4. Materials and Methods

The research results obtained and analyzed show the mutual connections, from the questionnaire survey, which was part of the research project VEGA no. 1/0621/17 entitled: ‘Decision-making process of Slovak households about allocation of time for paid and unpaid work and household strategies impact on selected areas of the economic practice.’ One of the partial intentions of the project was to examine the area of commuting to and from work. The research team consisted of academic experts in economics, sociology, demography, statistics and psychology, who participated in the creation of the questionnaire (as the main tool for data collection). A questionnaire with multiple choice options was chosen in order to obtain the most objective initial national picture of the impact of selected determinants on the travel mode of commuting. The method of obtaining information chosen in this way most reveals the behavior of individuals at the individual level with relatively extensive data on attendance, which can be evaluated in the econometric model. This methodology assumes that the way of commuting to and from work will be mainly influenced by explicit and implicit (time) costs. Research studies by Holmgren [

64] and Dargay [

65] were the inspiration for us in this direction.

The questionnaire, consisting of several interconnected parts (modules), was distributed by trained interviewers to more than 700 Slovak households (with more than 1800 members) in the months of April–May 2018 and enabled the research team to obtain relatively broad-spectrum data. The data were collected from the seventh module, which was focused on the area of commuting. The research sample of respondents were reduced to 15–64 years old who in 2017 had at least one paid job. The research sample consisted of 1014 economically active respondents (56% men, 44% women). The average age of respondents was 38 years (a quarter of respondents was in the age category of 40–49 years old). The largest part consisted of secondary school-educated (more than 70%) and full-time employed (almost 80%) respondents working in the private sector of the economy (almost 80%). Most of them (93.1%) had only one paid job at the time of the survey, worked in the Slovak Republic (95%) and commuted daily (91%). Almost half of the respondents belonged to the income category from 401 to 800 euro. It is important to note that the participation in the questionnaire survey was voluntary (unpaid), with the result that the number of answers does not always coincide with the absolute number of respondents. More detailed description of the research sample in terms of age, education and income category is presented in

Table 1.

The obtained data were processed and evaluated with the use of statistical software SPSS (version 25) and selected statistical methods (e.g., descriptive statistics, Nominal Logistic Regression, Fischer’s Exact test, Mann-Whitney Test, Cochran Test, McNemar Test).

The aim of the article is to review demographic and economic determinants influencing the travel mode choice and to determine its impact on the subjective well-being of respondents. In connection with the aim, we have formulated two research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). We assume that the travel mode choice of respondents is influenced by selected demographic and economic determinants.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). We assume that the travel mode affects the subjective well-being of the respondents.

Following the testing of the first hypothesis—using Nominal Logistic Regression, we chose the travel mode as the explained variable, while we considered the explanatory variables (related to employed respondents) that entered the model (and we had the opportunity to test them). In

Table 2, we provide a more detailed description of the variables that entered the model.

We used the logistic regression to measure the functional relationship between the qualitative dependent variable and the quantitative and qualitative independent variables. A similar approach to identifying the influence of various determinants on the travel mode of commuting was applied by, e.g., Wójcik [

66] and Sivasubramanivam et al. [

67]. Due to the nature of the primary data, especially the independent variables, we consider the use of logistic regression to be an appropriate method for evaluating them within one model.

By default, research dealing with the analysis of commuting and its determinants takes into account the basic demographic (socio-economic) characteristics of respondents, which helps to generalize knowledge and draw conclusions that are more specific. In selecting possible demographic and economic determinants potentially affecting travel mode choice, we relied on many research studies [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77]. The common feature of these studies was the effort to review determinants (age, gender, status, education level, earnings, etc.) that affect commuting and their generalization. It turns out that the decision making of individuals and households about commuting issues is predominantly aimed at achieving a subjective well-being (or work-life balance), which is largely conditioned by the attitudes, family circumstances and economic choices of the individuals or households.

To evaluate the impact of the travel mode of commuting to and from work on subjective well-being, we used the recommended Likert scale with regard to retrospective data in the questionnaire, which helped us to verify the second hypothesis. Our approach is in line with, e.g., De Vos et al. [

78] and Ettema et al. [

48], who, as well as others, used this psychometric instrument to measure retrospectively felt SWB.

In connection with the second hypothesis, we are aware that the issue of SWB is a broad concept, presented in the previous section. In accordance with the intention of the article, in our survey, we focused only on the evaluation of respondents’ attitudes in connection with travel mode and their satisfaction as a subjective measure. Travel mode is one of the aspects that affect the overall satisfaction, and thus SWB, of one’s life. The respondents were asked to express their attitude on a five-point scale—very positive impact, rather positive impact, neutral attitude, rather negative impact, very negative impact. The whole essence of SWB is rather simplified (which we consider a considerable limitation of our research), but can capture the real feelings and experiences of respondents.

We consider it an advantage of our research that the data were provide retrospectively, which could have contributed to higher objectivity of the results. This memory- based (retro) approach of SWB measurement requires the respondent to assess the intensity (not the frequency) of satisfaction or emotional states, over a period of time and on an appropriate scale [

79]. When testing the second hypothesis, we chose the subjective feeling of respondents in connection with travel mode as the explained variable and considered travel mode as the explanatory variable. We applied a Fisher’s test to verify the dependence and differences in the influence of the travel mode of commuting to subjective well-being. We applied further the mean rank as the method that led to the identification of the impact of the travel mode of commuting on subjective well-being of respondents.

5. Results and Discussion

Given the data, at the beginning of the analysis we had verified whether there are significant differences in the travel mode of respondents. When choosing the travel mode options, which we explored in the questionnaire survey, we relied primarily on real options and generally known facts. It was possible to travel with one’s own car, to use public transport, including city transport and train transport, to use a shared car, to travel by bicycle or on foot and to commute by other modes. Based on results of testing by the Cochran Test, it is obvious that there are significant differences between the individual commute modes. To evaluate the most often used mode of commuting, we used descriptive statistics. The results are presented in

Table 3.

Intuitively and based on the results of many studies, we assumed that the most-used travel mode would be commuting by one’s own car. Based on the results of the questionnaire survey, almost half of the respondents travel to and from work by their own car. By further statistical testing using the McNemar Test, we found that commuting by one’s own car is the most-used mode of commuting, even compared to all other modes. Based on this, we dare to state that Slovakia is not different from most developed countries, where economically active individuals prefer their own car by commuting to and from work. “Another type of travel mode” has been noticed as the least used method. We believe that this mode could consist of, e.g., commuting by company car, taxi or other modes not offered in the questionnaire. Due to the low response rate, “another type of travel mode” was not analyzed further. About one-fifth of respondents used public transport to commute and only 15% used a bicycle or walked. Due to the knowledge of the state of transport infrastructure and bicycle transport in Slovakia, such results were expected.

It is obvious that each commuter tries to eliminate the negative effects to which they are regularly exposed during commuting, and chooses the optimal way in terms of time as well as monetary costs and other factors that affect experience during commuting. Traveling to work, especially over longer distances, does not always have to be just “dead” time, which also costs money (double loss); on the contrary, it can be useful for a commuter, depending on their preferences for spending time in the means of transport. Traveling not only by public transport in combination with modern information and communication technologies offers several possibilities that the commuter can use effectively, among other things, for the benefit of their development, which clearly allows them to reduce the passivity during commuting. Applying multitasking in different areas of life is one of the features of productivity, efficiency and a modern way of life. Scientific studies have declared that multitasking also takes place when commuting to and from work [

80,

81].

From our results, we cannot interpret whether commuters also used another mode of travel than what they stated in the questionnaire, or a combination of several modes. We consider that some commuters would use a different type of travel mode, but there are reasons that prevent them from meeting their expectations. An example can be a low-income commuter who uses public transport but would rather travel by car but cannot afford it. However, the indicated context goes beyond the questionnaire survey, but we consider it necessary to identify it in the future. We assume that this fact limits the interpretation of our results. Deeper knowledge of commuting patterns could lead to better understanding of the use of different travel modes and the behavior of commuters. It is possible that our respondents also occasionally use the modal mode of travel, which should represent the future in the development of sustainable transport in the 21st century. Probably, a lot depends on the distance of the place of work, the available technical infrastructure, the economic conditions of commuters and also the weather conditions. There is a broader area for further research on the conditions of the Slovak Republic and identification of restrictions that prevent commuters from using the most preferred mode of transport from their point of view, as well as to estimate the tendency to propensity in the behavior of commuters to other mode of travel. However, we believe that our results can provide a minimal starting point for further research of travel mode of commuting to work.

In connection with the aim of the article, a hypothesis was formulated that the travel mode choice of respondents is influenced by selected demographic and economic determinants. In selecting the determinants, we used various research studies (listed in Materials and Methods). The obtained data were used in a statistical model to find out which of the determinants we examined have an impact on the travel mode choice, and thus, have come to a deeper understanding of commuters and their needs. These findings may contribute to the discussion on the further development of transport infrastructure in Slovakia in a broader context. The results of the Nominal Logistic Regression model are attached in

Table 4, which consists of several consecutive components.

Based on the test results, the formulated hypotheses were only partially confirmed. Determinants significantly influencing travel mode choice are the average weekly length of commuting, the average weekly commuting costs, income category, gender, education, type of employment and place of work. The other determinants (variables) that entered the model did not appear to be significant in this test, and thus, do not affect the travel mode choice. With a Nagelkerke value of 0.735, it can be stated that the quality of the statistical model is satisfactory. Even in this case, we can assume that if we had other possible variables and tested them in one model, the results could be different. This can be considered as a partial limitation of our conclusions, as there is no similarly focused research in Slovakia and we cannot compare our results with other domestic scientific studies. Thus, we consider our conclusions to be primary and original, albeit with a limited possibility of interpretation. From the results of the analysis of the obtained data, we also state that, on average, men spend more time commuting per week than women and that with the growth of income from paid work, travel expenses and length of commuting of respondents increase.

The next part of the article focuses on linking the issue of commuting to and from work with the private lives of respondents. The identification of the impact of the travel mode on the commuters’ SWB can be a key argument in enforcing certain public policy measures. In connection with the aim of the article, we have formulated the second hypothesis that the travel mode affects the SWB of respondents. Based on the results of Fisher’s Exact Test, there are significant differences in the travel modes and their impact on SWB of respondents. The Kruskal-Wallis Test also confirmed this fact. The results of the testing determined that the satisfaction of respondents is different for different travel modes, and from a statistical point of view, it is valid to look for other contexts.

The obtained data show that the respondents who commute by bicycle or on foot are the most satisfied, and thus, this way of commuting has the most positive effect on their SWB. Relatively satisfied are those respondents who travel by their own or a shared car. On the contrary, the least satisfied are those who travel by public transport. The value ranges from 100 and higher (see

Table 5).

The information was obtained retrospectively, and thus, reduced the rate of emotional responses. In our opinion, our data provide a more objective picture of how the travel mode affects the SWB of respondents, as we asked them for the period of 2017. The information obtained, therefore, takes into account the judicious expression of more stable attitudes. Using three partial Mann-Whitney Tests confirmed that commuting to and from work by bicycle or on foot is preferred in terms of impact on SWB over using one’s own car, public transport and a shared car.

Based on the analysis of the data obtained by the questionnaire survey, we came to several interesting conclusions. Slovaks prefer their own car when commuting, which does not differ from other countries [

82,

83,

84]. In connection with the global trend and the currently considerably congested road infrastructure, especially in larger cities, the Government of the Slovak Republic intends to build sustainable transport in the context of the green economy. In this context, it aims to increase the use of public transport and cycle transport, especially in the context of daily commuting. We believe that in order for individuals to be willing to change their habits and travel mode, we need to know the determinants that affect their travel mode choice. In this article, we examined some selected demographic and economic determinants and their impact on the travel mode choice of respondents. We found that the travel mode choice is influenced by the length of commuting (commuting time costs), commuting financial costs, the income of respondents, their education, gender, type of employment and place of work. On the contrary, travel mode choice is not affected by the length of time spent by paid work, the sector of the economy in which they work, the organization of work nor the financial or non-financial benefits. Based on the above, we believe that commuters strive to optimize primarily time and financial costs by travel mode choice. In addition, travel mode choice may be different due to gender and education (probably the related income level) of respondents. In connection with the length of commuting time, it is logical to take into account the place of work. We are aware that we did not consider all possibilities, as we examined only the basic determinants, which we chose intuitively and based on other scientific studies assumed as possibly influencing the travel mode choice. Nevertheless, these findings are important in terms of building and developing sustainable transport in Slovakia.

The impact of travel mode on the private life of individuals, and thus their subjective feeling of satisfaction/dissatisfaction with respect to travel mode, is one of the aspects of SWB. Slovaks do not seem to be different from other nations. According to our findings, the respondents are the most satisfied when they commute by bicycle or on foot. Nevertheless, they use this travel mode the least. Given the current state of infrastructure and bicycle traffic in Slovakia, the low proportion of respondents using this travel mode did not surprise us. In 2015, the Government of the Slovak Republic approved the National Strategy for the Development of Bicycle Transport and Cycling in the Slovak Republic [

85]. The vision of the strategy is to equalize bicycle transport with other modes of transport so that it becomes a full-fledged part of urban and regional transport systems. In our opinion, this vision is being fulfilled only very slowly.

In general, it can be stated state that in Slovak towns and villages, there are discontinuous sections of cycle paths, which were mostly built non-conceptually. The possibilities of bicycle parking (at public institutions, railway and bus stations, shopping centers) and their transport by public transport do not correspond to the trend either. An even more widespread problem in urban agglomerations in Slovakia is the poor technical condition of the road infrastructure as a whole, as in the absence of a network of segregated bicycle roads, cyclists are dependent on road traffic, where car traffic dominates. Spatial plans of towns and municipalities often do not even consider the design of the necessary infrastructure, which makes it impossible to plan the development of bicycle transport in perspective. In contrast, in the open country, there is a network of more than 10,000 km of marked cycling routes, using mostly roads serving primarily other purposes.

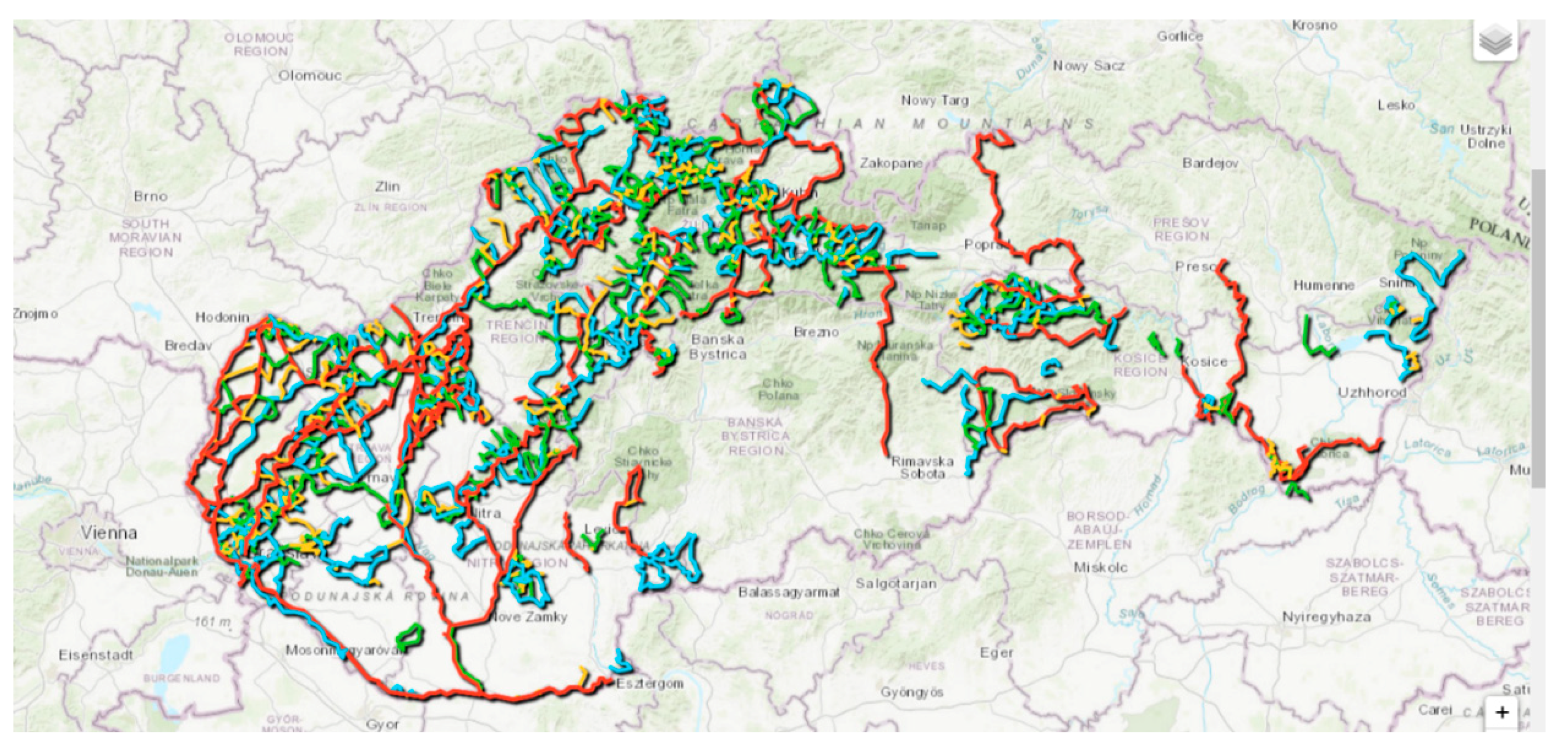

The network of cycle routes in Slovakia is shown in

Figure 1. In terms of their importance, transnational (EuroVelo) routes and long-distance routes marked in red have the greatest contribution to daily commuting. Not to be overlooked are the blue cycle routes, which mark parallel routes to EuroVelo routes and long-distance cycle routes. The densest and most diverse network of cycling infrastructure in Slovakia is developed in the western and northern part of the territory, which can be considered positive with regard to the population density of this area and the unfavorable traffic situation, which is worst in the capital and its surroundings. Bratislava and its surroundings can be considered the most congested area of Slovakia, which is characterized by the fact that even short distances to work are time consuming compared to the area where a commuter can cover a greater distance in less time. There are currently 98 km of red cycle paths and 148 km of blue cycle paths built in Bratislava. The less favorable condition of the cycling infrastructure is in the eastern and southern part of Slovakia, where the network of cycling routes is much less dense compared to the economically more developed west.

While the respondents are relatively satisfied when using their own and a shared car, they are the most dissatisfied when traveling by public transport. It is obvious that the attractiveness of public transport in Slovakia is currently very low. Public transport infrastructure is insufficient—in many cases, urban transport does not follow interurban paths, which prolongs travel time and often makes it impossible to commute. Moreover, buses and trains themselves are obsolete and do not provide comfort to travelers. In this context, it is necessary to optimize the public transport network, increase its quality and ensure the continuity of trains and buses.

The impacts of travel mode on the SWB of respondents can be considered as the key findings. According to the transport reform plan, the competent authorities are aware of these facts. However, it is essential that the situation is solved conceptually and systemically and that a sufficiently large amount of funding is allocated to the reform of public transport and cycle transport conceived in this way. For this reason, we consider it important to stimulate professional discussion at the societal level.

6. Conclusions

Thus far, in the conditions of the Slovak Republic, there is no wider scientific and professional knowledge that is devoted to the issue of daily commuting to work, despite the fact that it is an essential part of everyday life of an economically active population. We believe that this is a topical issue with regard to the fact that it concerns not only commuters and their subjective experience, the allocation of time and labor productivity, but also has a significant impact on the household and home management. Finally yet importantly, commuting affects society, life in municipalities and cities in relation to transport and traffic, the environment and the overall quality of life in a given environment. The Slovak Republic is a country with a small area (49,035 km2), internally divided with various reliefs, which have a significant influence on the travel mode choice in individual parts of the country. Regularly changing seasons are also one of many external factors to which commuters must adapt. These limitations, in a certain way, combined with the possibilities and preferences of the commuters, also result in habits in connection with travel mode choice.

One of the priorities of the Government of the Slovak Republic is the green economy, and within it, sustainable transport. The stated goal is for transport infrastructure to be developed based on a financially and environmentally sustainable long-term investment plan in order to increase the attractiveness of public transport and support non-motorized forms of transport. This intention is also in line with the global trend.

Attempts to develop sustainable transport policies need to be based on a diagnosis of the main motives for car use and the determinants discouraging the uptake of alternative modes. For any non-car mode to increase its competitiveness, it must be able to adapt to meet commuters’ ever rising requirements. Based on the results of the analysis, we found that the determinants that affect the travel mode choice of respondents include commuting time costs, commuting financial costs, income of respondents, their education, gender, type of employment and place of work. These conclusions are consistent with the scientific studies of Holmgren [

64] and Dargay [

65].

We also found that the most preferred travel mode of respondents is to commute by their own car and, conversely, the least preferred travel modes is to commute by bicycle and on foot. We consider it an important finding that the respondents are the most satisfied when commuting by bicycle or on foot and the most dissatisfied when commuting by using public transport. The direction of transport policy seems to be the right one in this regard, and reform is necessary. The inspiration for us could be the countries of Western Europe, which have had their national cycling strategies developed for several decades. Their implementation has resulted in several countries receiving a double-digit share of bicycle transport in the mobility of the urban population, such as the Netherlands (27%), Denmark (19%) and Germany (10%). Several Dutch cities account for 35% to 40% of bicycle traffic on all journeys. A high proportion (more than 30%) are cities where cycling has always been an equal part of transport policy [

87].

However, regarding questions about economic efforts to protect the environment, Slovakia belongs among countries present themselves as unwilling. Less developed countries present less environmentally healthy attitudes than the more developed ones [

63]. That is why we consider it important to stimulate a broad public debate and to improve the public’s awareness of the benefits of public transport and cycling as a more environmentally, economically and health-friendly travel mode. The current situation in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant increase in cyclists. The positive effect of that has been the higher effort of territorial self-governing regions and some towns and municipalities to solve issues with bicycle transport in their territories. At the national level, however, this situation has not been reflected on yet.