A Central Element of Europe’s Football Ecosystem: Competitive Intensity in the “Big Five”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem of Professional European Football

3. Literature Review

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Measurement of CI

4.2. Data Collection

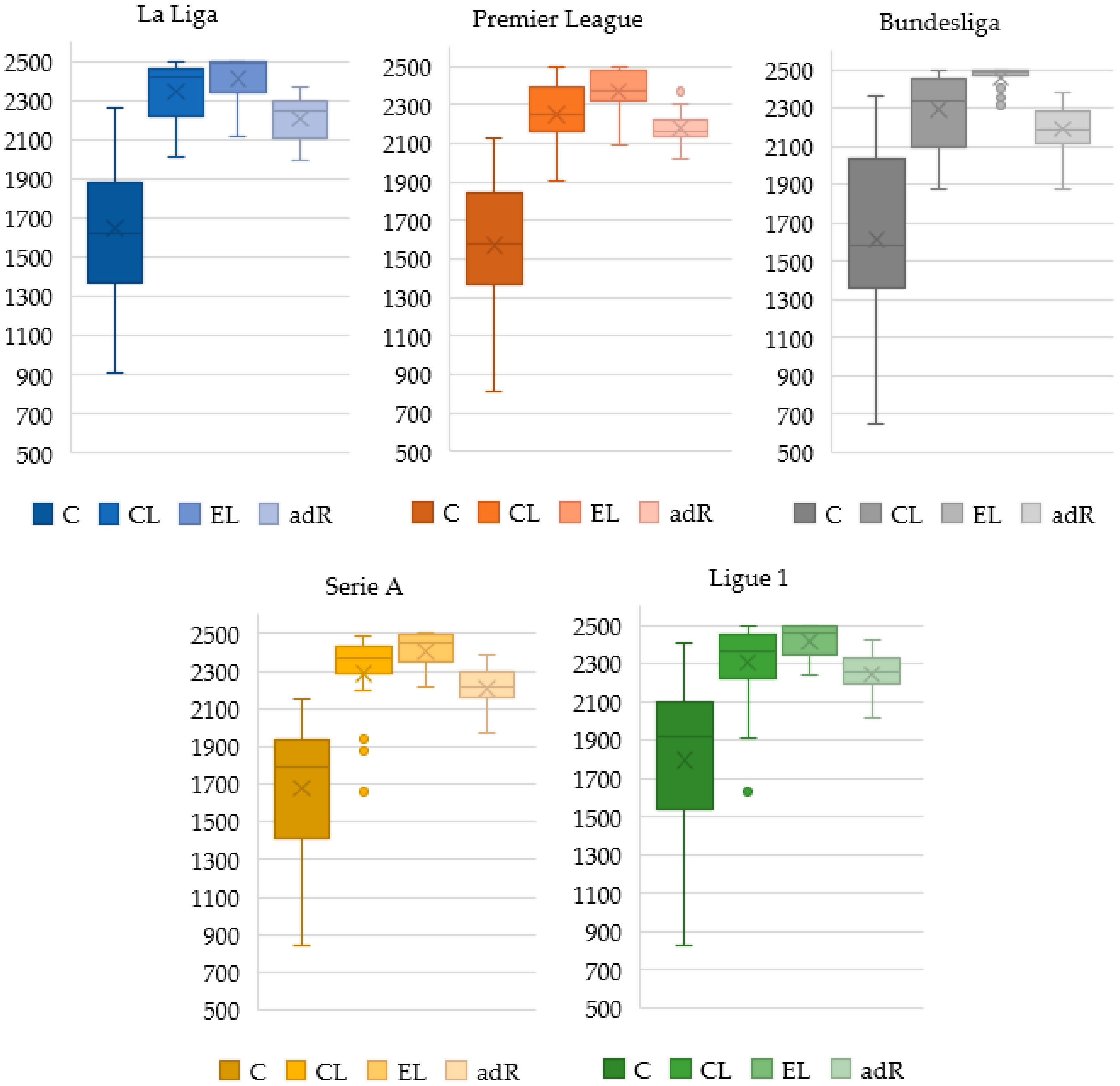

5. Results

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| La Liga | Premier League | Bundesliga | Serie A | Ligue 1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | EL | adR | CL | EL | adR | CL | EL | adR | CL | EL | adR | CL | EL | adR | |

| 2018/19 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 4 | 18 |

| 2017/18 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| 2016/17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 18 |

| 2015/16 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 17 |

| 2014/15 | 4 | 7 | 18 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 17 |

| 2013/14 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2012/13 | 4 | 9 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 16 | 3 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2011/12 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 16 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2010/11 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 16 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 17 |

| 2009/10 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2008/09 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 8 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2007/08 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2006/07 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 15 | - | - | - | 3 | 4 | 17 |

| 2005/06 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 15 | - | - | - | 3 | 4 | 17 |

| 2004/05 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 15 | - | - | - | 3 | 4 | 17 |

| 2003/04 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 15 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2002/03 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 3 | 5 | 17 |

| 2001/02 | 4 | 7 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 16 |

| 2000/01 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 3 | 5 | 15 |

| 1999/00 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 3 | 5 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 4 | 15 |

| 1998/99 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 3 | 7 | 15 |

| Ø | 4.0 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 3.8 | 6.1 | 17.0 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 15.5 | 3.7 | 6.6 | 16.2 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 16.8 |

| La Liga | Premier League | Bundesliga | Serie A | Ligue 1 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | |

| 2018/19 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 33 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 33 | 37 | 37 | 38 |

| 2017/18 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 35 | 33 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 29 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| 2016/17 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 35 | 37 | 31 | 31 | 34 | 33 | 37 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 33 | 36 | 38 |

| 2015/16 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 33 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 30 | 38 | 37 | 38 |

| 2014/15 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 34 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 30 | 30 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 37 |

| 2013/14 | 38 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 27 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| 2012/13 | 35 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 34 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 28 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 35 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| 2011/12 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 32 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 38 |

| 2010/11 | 37 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 32 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 38 |

| 2009/10 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 36 |

| 2008/09 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 38 | 38 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 38 |

| 2007/08 | 35 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 31 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| 2006/07 | 38 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 34 | - | - | - | - | 33 | 38 | 38 | 36 |

| 2005/06 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 33 | 33 | 34 | 34 | - | - | - | - | 33 | 38 | 38 | 36 |

| 2004/05 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 35 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 31 | 34 | 34 | 33 | - | - | - | - | 35 | 36 | 38 | 38 |

| 2003/04 | 36 | 35 | 38 | 37 | 35 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 38 | 35 | 37 | 38 |

| 2002/03 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 30 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| 2001/02 | 37 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 38 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 34 |

| 2000/01 | 36 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 37 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| 1999/00 | 37 | 38 | 36 | 37 | 34 | 38 | 37 | 38 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 33 | 31 | 34 | 33 | 34 |

| 1998/99 | 35 | 38 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 35 | 36 | 38 | 31 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 33 | 34 |

| Ø DM after 38 MDs | 36.6 | 37.3 | 37.4 | 37.4 | 36.1 | 37.1 | 37.2 | 37.7 | 36.1 | 37.5 | 37.3 | 37.5 | 35.6 | 37.2 | 37.6 | 37.6 | ||||

| Ø DM after 34 MDs | 31.8 | 33.2 | 33.8 | 33.8 | 33.3 | 33.2 | 33.7 | 33.8 | 33.0 | 34.0 | 33.3 | 34.0 | ||||||||

| Ø DM in % | 96.4 | 98.2 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 95 | 97.7 | 98 | 99.1 | 93.6 | 97.8 | 99.4 | 99.3 | 96.0 | 98.3 | 98.4 | 99.0 | 94.4 | 98.2 | 98.7 | 99.1 |

| La Liga | Premier League | Bundesliga | Serie A | Ligue 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | C | CL | EL | adR | ||||||

| contribution in % | contribution in % | contribution in % | contribution in % | contribution in % | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2018/19 | 8900.6 | 18.2 | 27.9 | 27.9 | 25.9 | 7974.3 | 15.1 | 29.5 | 29.7 | 25.7 | 8619.7 | 20.9 | 28.5 | 28.9 | 21.8 | 8083.8 | 15.5 | 29.6 | 27.4 | 27.5 | 7824.6 | 15.5 | 28.2 | 29.5 | 26.7 |

| 2017/18 | 7834.0 | 16.3 | 26.4 | 31.9 | 25.4 | 7587.4 | 10.7 | 29.7 | 31.2 | 28.5 | 8226.6 | 12.9 | 30.2 | 30.3 | 26.6 | 8358.9 | 15.8 | 27.8 | 29.8 | 26.6 | 7983.1 | 14.2 | 27.1 | 31.3 | 27.5 |

| 2016/17 | 7944.8 | 18.9 | 27.8 | 27.9 | 25.4 | 7840.7 | 17.2 | 28.3 | 26.9 | 27.5 | 7961.0 | 16.5 | 24.9 | 31.3 | 27.4 | 7626.7 | 20.0 | 21.8 | 30.7 | 27.4 | 7347.9 | 17.9 | 22.2 | 30.5 | 29.4 |

| 2015/16 | 8310.6 | 19.4 | 28.1 | 25.4 | 27.1 | 9015.1 | 20.5 | 27.0 | 27.5 | 25.0 | 7961.7 | 14.0 | 29.4 | 29.6 | 27.0 | 7983.1 | 17.1 | 23.5 | 31.2 | 28.2 | 7926.5 | 10.5 | 30.9 | 29.9 | 28.7 |

| 2014/15 | 8218.2 | 16.7 | 27.0 | 30.4 | 25.9 | 8279.7 | 17.5 | 27.1 | 28.5 | 26.8 | 7961.1 | 17.1 | 23.5 | 31.1 | 28.3 | 8170.9 | 17.7 | 29.2 | 29.0 | 24.1 | 8776.1 | 21.4 | 26.8 | 26.7 | 25.1 |

| 2013/14 | 8307.7 | 20.0 | 25.6 | 27.0 | 27.4 | 8419.8 | 22.0 | 24.0 | 28.4 | 25.7 | 7501.0 | 8.7 | 32.0 | 33.3 | 25.9 | 7268.0 | 11.6 | 26.7 | 34.4 | 27.3 | 8700.3 | 17.7 | 27.0 | 28.6 | 26.7 |

| 2012/13 | 7892.2 | 11.6 | 30.9 | 31.2 | 26.3 | 8013.4 | 17.1 | 28.7 | 27.5 | 26.6 | 7752.7 | 8.4 | 32.0 | 32.2 | 27.3 | 8404.7 | 18.2 | 27.7 | 29.0 | 25.1 | 8949.9 | 19.9 | 27.1 | 27.6 | 25.4 |

| 2011/12 | 8289.9 | 11.7 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 28.1 | 8597.7 | 19.9 | 27.6 | 27.0 | 25.5 | 8192.5 | 17.7 | 27.9 | 28.6 | 25.8 | 8996.9 | 20.4 | 27.4 | 26.3 | 25.9 | 8801.6 | 22.9 | 23.2 | 28.3 | 25.6 |

| 2010/11 | 8226.5 | 15.3 | 27.1 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 8902.8 | 22.3 | 24.3 | 27.9 | 25.6 | 8496.2 | 20.3 | 25.6 | 27.2 | 26.9 | 9007.6 | 21.3 | 27.1 | 27.4 | 24.2 | 9345.4 | 22.5 | 26.3 | 25.4 | 25.8 |

| 2009/10 | 8062.7 | 14.2 | 30.7 | 29.4 | 25.8 | 8460.7 | 21.9 | 26.6 | 27.7 | 23.8 | 9157.1 | 23.5 | 26.3 | 27.1 | 23.1 | 8889.2 | 22.7 | 27.3 | 25.2 | 24.8 | 8721.8 | 22.2 | 26.9 | 27.4 | 23.4 |

| 2008/09 | 8852.9 | 18.3 | 27.4 | 28.0 | 26.3 | 8149.6 | 19.3 | 24.2 | 30.3 | 26.1 | 9006.2 | 24.3 | 26.0 | 26.7 | 23.1 | 8838.7 | 19.7 | 27.2 | 28.3 | 24.8 | 9060.0 | 23.1 | 24.6 | 27.2 | 25.1 |

| 2007/08 | 8913.6 | 18.1 | 27.6 | 28.0 | 26.4 | 8413.4 | 21.5 | 23.7 | 29.1 | 25.7 | 8363.1 | 18.9 | 24.8 | 29.8 | 26.6 | 8770.4 | 21.6 | 27.8 | 25.6 | 25.0 | 9434.4 | 22.6 | 26.3 | 26.5 | 24.7 |

| 2006/07 | 9180.7 | 24.2 | 23.8 | 27.2 | 24.8 | 8418.2 | 18.3 | 25.7 | 29.7 | 26.4 | 8987.6 | 24.0 | 22.5 | 27.8 | 25.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 8658.8 | 17.9 | 28.9 | 28.9 | 24.3 |

| 2005/06 | 8712.8 | 20.8 | 27.6 | 26.8 | 24.8 | 8319.2 | 17.4 | 29.1 | 28.2 | 25.3 | 8648.2 | 21.2 | 24.2 | 28.9 | 25.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 8456.2 | 17.3 | 29.3 | 29.5 | 23.9 |

| 2004/05 | 9062.9 | 20.3 | 27.4 | 27.5 | 24.8 | 8126.6 | 14.5 | 29.0 | 30.7 | 25.8 | 8593.4 | 17.9 | 28.4 | 28.7 | 25.0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8869.9 | 20.3 | 25.0 | 28.2 | 26.5 |

| 2003/04 | 8702.1 | 22.6 | 23.1 | 28.7 | 25.6 | 8536.1 | 16.5 | 29.2 | 29.3 | 25.0 | 8835.5 | 20.0 | 26.2 | 28.0 | 25.8 | 8342.0 | 16.7 | 29.2 | 28.2 | 25.8 | 8631.5 | 24.6 | 22.1 | 27.2 | 26.1 |

| 2002/03 | 9126.8 | 23.7 | 25.8 | 27.4 | 23.1 | 9163.1 | 20.5 | 26.4 | 27.2 | 25.9 | 8843.3 | 17.1 | 27.7 | 28.2 | 27.0 | 8934.4 | 20.6 | 25.5 | 27.7 | 26.2 | 9570.6 | 25.1 | 25.6 | 25.7 | 23.5 |

| 2001/02 | 9416.0 | 22.7 | 26.2 | 26.5 | 24.7 | 8097.1 | 20.0 | 26.0 | 25.8 | 28.1 | 8815.8 | 24.4 | 23.7 | 28.1 | 23.7 | 9480.0 | 22.3 | 26.2 | 26.3 | 25.1 | 9286.9 | 24.6 | 26.3 | 24.9 | 24.3 |

| 2000/01 | 9053.7 | 20.7 | 27.3 | 27.6 | 24.4 | 8758.4 | 19.1 | 27.3 | 28.4 | 25.2 | 9649.2 | 24.5 | 25.6 | 25.7 | 24.2 | 8802.7 | 22.1 | 24.9 | 26.7 | 26.3 | 9414.6 | 22.2 | 25.9 | 26.5 | 25.3 |

| 1999/00 | 9225.2 | 24.6 | 26.7 | 24.2 | 24.6 | 8196.5 | 15.7 | 29.6 | 28.3 | 26.4 | 9367.6 | 21.7 | 26.6 | 26.7 | 25.0 | 9111.6 | 22.8 | 25.4 | 27.4 | 24.4 | 9166.7 | 21.0 | 27.0 | 25.6 | 26.4 |

| 1998/99 | 8648.0 | 20.9 | 28.3 | 27.1 | 23.7 | 8514.6 | 25.0 | 22.4 | 25.5 | 27.0 | 8613.4 | 17.4 | 28.6 | 27.2 | 26.8 | 9308.1 | 23.1 | 25.1 | 26.4 | 25.4 | 9038.6 | 23.0 | 26.1 | 26.0 | 24.9 |

| Ø | 8613.4 | 19.0 | 27.3 | 28.0 | 25.7 | 8370.7 | 18.7 | 26.9 | 28.3 | 26.1 | 8550.1 | 18.6 | 26.9 | 28.8 | 25.7 | 8576.5 | 19.4 | 26.6 | 28.2 | 25.8 | 8760.3 | 20.3 | 26.3 | 27.7 | 25.7 |

| sd | 492.3 | 414.9 | 580.5 | 588.6 | 584.6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Dimitropoulos, P.; Leventis, S.; Dedoulis, E. Managing the European football industry: UEFA’s regulatory intervention and the impact on accounting quality. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 459–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numerato, D. Football Fans, Activism and Social Change; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1317432711. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, F.C.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial ecosystems. Use Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2016, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, A.; Ghezzi, A.; Balocco, R. Entrepreneurial ecosystem research: Present debates and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1291–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plumley, D.; Ramchandani, G.; Wilson, R. The unintended consequence of Financial Fair Play: An examination of competitive balance across five European football leagues. Sportbus. Manag. Int. J. 2019, 9, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, M.; Rebeggiani, L. Die European Super League im Fußball-mögliche Szenarien aus sport- und wettbewerbsökonomischer Sicht. Sciamus Sport Manag. 2019, 10, 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, F.; Preuss, H.; Könecke, T. Measuring competitive intensity in sports leagues. Sportbus. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 10, 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringstad, M.; Gerrard, B. The concepts of competitive balance and uncertainty of outcome. In The Economics and Management of Mega Athletic Events: Olympic Games, Professional Sports, and Other Essays; Papanikos, G.T., Ed.; Athens Institute for Education and Research: Athens, Greece, 2004; pp. 115–130. ISBN 960-87822-9-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kringstad, M.; Gerrard, B. Theory and Evidence on Competitive Intensity in European Soccer. In Proceedings of the International Association of Sports Economists Conference, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 18–19 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kringstad, M.; Gerrard, B.; Competitive Balance in a Modern League Structure. Abstarct at North American Society for Sport Management Conference (NASSM). Available online: https://www.nassm.com/files/conf_abstracts/2007_1715.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2020).

- Bond, A.J.; Addesa, F. Competitive Intensity, Fans’ Expectations, and Match-Day Tickets Sold in the Italian Football Serie A, 2012–2015. J. Sports Econ. 2020, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stam, E.; Bosma, N.; van Witteloostuijn, A.; de Jong, J.; Bogaert, S.; Edwards, N.; Jaspers, F. Ambitious Entrepreneurship: A Review of the Academic Literature and New Directions for Public Policy; Adviesraad voor Wetenschap en Technologie-beleid (AWT): Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-90-77005-56-9. [Google Scholar]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C.; Popp, B. The sport value framework–a new fundamental logic for analyses in sport management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F.; Akaka, M.A.; He, Y. Service-dominant logic. Rev. Mark. Res. 2010, 6, 125–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrand, A.; Chappelet, J.-L.; Séguin, B. Olympic Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 0415587875. [Google Scholar]

- Horbel, C.; Popp, B.; Woratschek, H.; Wilson, B. How context shapes value co-creation: Spectator experience of sport events. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsiotsou, R.H. A service ecosystem experience-based framework for sport marketing. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 478–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohs, R.; Wieser, V.E.; Pristach, M. Value cocreation at sport events. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Fajardo, P.; Núñez-Pomar, J.M.; Ratten, V.; Crespo, J. Entrepreneurship and innovation in soccer: Web of science bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Annual Review of Football Finance 2020: Home Truths. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/uk/en/pages/sports-business-group/articles/annual-review-of-football-finance.html (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Brand Finance. Brand Finance Global 500. 2019. Available online: https://brandfinance.com/knowledge-centre/reports/brand-finance-global-500-2019/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- UEFA. Benchmarking Report Highlights Profits and Polarisation. Available online: https://www.uefa.com/insideuefa/protecting-the-game/club-licensing/news/newsid=2637880.html (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- The Nielsen Company. Fan Favorite: The Global Popularity of Football Is Rising. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/eu/en/insights/article/2018/fan-favorite-the-global-popularity-of-football-is-rising/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Goal. Goal 50 2020: The Best 50 Players in the World. Available online: https://www.goal.com/en/lists/goal-50-2020-the-best-50-players-in-the-world/1drx0x11z7i8a17j14njsth0ew (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Birkhäuser, S.; Kaserer, C.; Urban, D. Did UEFA’s financial fair play harm competition in European football leagues? Rev. Manag. Sci. 2019, 13, 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramchandani, G.; Plumley, D.; Boyes, S.; Wilson, R. A longitudinal and comparative analysis of competitive balance in five European football leagues. Team Perform. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 24, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y. Study on competitive balance of China Japan and Europe professional football leagues. China Sport Sci. 2017, 37, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, D.; Simmons, R.; Buraimo, B. Outcome uncertainty and the couch potato audience. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2005, 52, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humphreys, B.R. Alternative measures of competitive balance in sports leagues. J. Sports Econ. 2002, 3, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könecke, T. Das Modell der Personenbezogenen Kommunikation und Rezeption: Beeinflussung durch Stars, Prominente, Helden und andere Deutungsmuster; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3658191931. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, F.; Sala-Garrido, R.; Usai, A. The lack of balance in the Spanish first division football league. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H.; Form, L. Regulating Sport Leagues-The Case of Hockey India League. In Contemporary Sport Marketing: Global Perspectives; Zhang, J.J., Pitts, B.G., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2017; pp. 42–54. ISBN 9781351967341. [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, M. Breaking Bad or Breaking Even: A Multidimenional Perspective on UEFA Financial Fair Play. Ph.D. Thesis, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Mainz, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Terrien, M.; Andreff, W. Organisational efficiency of national football leagues in Europe. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2020, 20, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreff, W. Some comparative economics of the organization of sports: Competition and regulation in north American vs. European professional team sports leagues. Eur. J. Comp. Econ. 2011, 8, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fort, R. European and North American sports differences. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2000, 47, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Késenne, S. League management in professional team sports with win maximizing clubs. Eur. J. Sport Manag. 1996, 2, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, R.G. The organization of sports leagues. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2003, 19, 530–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sloane, P.J. The European model of sport. In Handbook on the Economics of Sport; Andreff, W., Szymanski, S., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Bodmin, UK, 2006; pp. 299–303. ISBN 978-1843766087. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrner, M. Teamsportmanagement; Oldenbourg: München, Germany, 2014; ISBN 978-3486755176. [Google Scholar]

- Könecke, T.; Schubert, M. Socio-economic doping and enhancement in sport: A case-based analysis of dynamics and structural similarities. In Contemporary Research in Sport Economics; Budzinski, O., Feddersen, A., Eds.; Peter Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 2014; pp. 97–114. ISBN 978-3-653-04103-3. [Google Scholar]

- Scelles, N.; Durand, C.; Bonnal, L.; Goyeau, D.; Andreff, W. Competitive balance versus competitive intensity before a match: Is one of these two concepts more relevant in explaining attendance? The case of the French football Ligue 1 over the period 2008–2011. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 4184–4192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.; Könecke, T. ‘Classical’doping, financial doping and beyond: UEFA’s financial fair play as a policy of anti-doping. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2015, 7, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennett, N. Attendances, uncertainty of outcome and policy in Scottish league football. Scott. J. Political Econ. 1984, 31, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimbridge, M.; Cameron, S.; Dawson, P. Satellite television and the demand for football: A whole new ball game? Scott. J. Political Econ. 1996, 43, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, J. Evaluating changes in league structure: The reorganization of the Scottish Football League. Appl. Econ. 1987, 19, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, S.M.; Goddard, J.A. The demand for standing and seated viewing accommodation in the English Football League. Appl. Econ. 1992, 24, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrooman, J. Theory of the beautiful game: The unification of European football. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2007, 54, 314–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, W.C. The peculiar economics of professional sports. Q. J. Econ. 1964, 78, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreff, W.; Scelles, N.; Walter, C. Neale 50 Years After: Beyond Competitive Balance, the League Standing Effect Tested with French Football Data. J. Sports Econ. 2015, 16, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelles, N.; Desbordes, M.; Durand, C. Marketing in sport leagues: Optimising the product design. Intra-championship competitive intensity in French football Ligue 1 and basketball Pro, A. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2011, 9, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowski, T.; Anders, C. Stadium attendance in German professional football–The (un) importance of uncertainty of outcome reconsidered. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2012, 19, 1553–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scelles, N.; Durand, C.; Bonnal, L.; Goyeau, D.; Andreff, W. My team is in contention? Nice, I go to the stadium! Competitive intensity in the French football Ligue 1. Econ. Bull. 2013, 33, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar]

- Scelles, N.; Durand, C.; Bonnal, L.; Goyeau, D.; Andreff, W. Do all sporting prizes have a significant positive impact on attendance in a European national football league? Competitive intensity in the French Ligue 1. Econ. Policy 2016, 11, 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraimo, B.; Simmons, R. Uncertainty of outcome or star quality? Television audience demand for English Premier League football. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2015, 22, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scelles, N. Star quality and competitive balance? Television audience demand for English Premier League football reconsidered. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2017, 24, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.J.; Addesa, F. TV demand for the Italian Serie A: Star power or competitive intensity? Econ. Bull. 2019, 39, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar]

- Baroncelli, A.; Caruso, R. The organization and economics of Italian Serie A: A brief overall view. Riv. Di Dirit. Ed. Econ. Dello Sport 2011, 7, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- DFL. Bundesliga Presents Global Growth Strategy. Available online: https://www.dfl.de/en/news/bundesliga-presents-global-growth-strategy/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Pawlowski, T.; Nalbantis, G.; Coates, D. Perceived game uncertainty, suspense and the demand for sport. Econ. Inq. 2018, 56, 173–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, S. Incentives and competitive balance in team sports. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2003, 3, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, S. UEFA champions league revenues, performance and participation 2003–2004 to 2016–2017. Manag. Sport Leis. 2018, 23, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, C.; Reeves, M.J.; Littlewood, M.A.; Nesti, M.; Richardson, D. Developing individuals whilst managing teams: Perspectives of under 21 coaches within English Premier League football. Soccer Soc. 2018, 19, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H.; Haugen, K.; Schubert, M. UEFA financial fair play: The curse of regulation. Eur. J. Sport Stud. 2014, 2, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, J. The impact of participation in pan-European competition on domestic performance in association football. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoye, R.; Smith, A.C.T.; Nicholson, M.; Stewart, B. Sport Management: Principles and Applications; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 1317557786. [Google Scholar]

| La Liga | Premier League | Bundesliga | Serie A | Ligue 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Club | Title | Club | Title | Club | Title | Club | Title | Club | Title |

| FC Barcelona | 7 | Manchester City | 4 | FC Bayern Munich | 8 | Juventus Torino | 8 | Paris Saint-Germain | 6 |

| Real Madrid | 2 | FC Chelsea | 3 | Borussia Dortmund | 2 | Inter Milan | 1 | AS Monaco | 1 |

| Atlético Madrid | 1 | Manchester United | 2 | - | - | AC Milan | 1 | Montpellier HSC | 1 |

| - | - | Leicester City | 1 | - | - | - | - | Lille CSO | 1 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Olympique Marseille | 1 |

| Author(s) | League(s) | Season(s) under Investigation | Sub-Competition (Variable) | Objective of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jennett (1984) [46] | Scottish Football League | 1975/76–1980/81 | championship, relegation | explaining attendance |

| Cairns (1987) [48] | Scottish Football League | 1971/72–1979/80 | championship, relegation | influence of league structure on attendance |

| Dobson and Goddard (1992) [49] | English Football League (Div. 1–4) | 1989/90–1990/91 | championship/promotion | explaining standing and seated attendance |

| Baimbridge et al. (1996) [47] | English Premier League | 1993/94 | championship, relegation | influence of TV broadcasting on attendance |

| Kringstad and Gerrard (2005) [9] | English Premier League | 1994/95–2003/04 | championship, UEFA CL, UEFA CL qualifiers, UEFA Cup, relegation | introducing CI measurement, comparison CB and CI |

| Scelles et al. (2011) [53] | French Ligue 1 and basketball Pro A | 2004–2009 | Ligue 1: championship, UEFA CL, UEFA CL qualifiers, UEFA Cup, UI Cup, relegation Pro A: six later 13 (playoffs) | introducing ICCI model, optimizing league design |

| Pawlowski and Anders (2012) [54] | German Bundesliga | 2005/06 | championship, UEFA CL | explaining attendance |

| Scelles et al. (2013a, 2013b) [44,55], Andreff and Scelles (2015) [52], Scelles et al. (2016) [56] | French Ligue 1 | 2008–2011 | championship, UEFA CL, UEFA CL qualifiers, UEFA EL, potential UEFA EL, potential UEFA EL qualifiers, relegation | explaining attendance |

| Buraimo and Simmons (2015) [57] | English Premier League | 2000/01–2007/08 | championship, qualification for UEFA CL or EL, relegation | explaining TV audience |

| Scelles (2017) [58] | English Premier League | 2013/14 | championship, UEFA CL, UEFA EL, potential UEFA EL, relegation | explaining TV audience |

| Bond and Addesa (2020, 2019) [11,59] | Italian Serie A | 2012/13–2014/15 | championship, UEFA CL, UEFA CL qualifiers, UEFA EL, UEFA EL qualifiers, relegation | explaining attendance (2020)/TV audience (2019) |

| Wagner et al. (2020) [7] | German Bundesliga | 1996/97–2017/18 | championship, UEFA CL (incl. qualifiers), UEFA EL (incl. qualifiers), avoid direct relegation | introducing CI-Index-Model, implications for league organizers |

1998/99–2008/09 | 2009/10–2018/19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Liga | 8990.4 | 8198.7 | 9416.0 | 2001/02 | 7834.0 | 2017/18 |

| Premier League | 8426.6 | 8309.2 | 9163.1 | 2002/03 | 7587.4 | 2017/18 |

| Bundesliga | 8883.9 | 8183.0 | 9649.2 | 2000/01 | 7501.0 | 2013/14 |

| Serie A | 8948.5 | 8279.0 | 9480.0 | 2001/02 | 7268.0 | 2013/14 |

| Ligue 1 | 9053.5 | 8437.7 | 9570.6 | 2002/03 | 7347.9 | 2016/17 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wagner, F.; Preuss, H.; Könecke, T. A Central Element of Europe’s Football Ecosystem: Competitive Intensity in the “Big Five”. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063097

Wagner F, Preuss H, Könecke T. A Central Element of Europe’s Football Ecosystem: Competitive Intensity in the “Big Five”. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063097

Chicago/Turabian StyleWagner, Fabio, Holger Preuss, and Thomas Könecke. 2021. "A Central Element of Europe’s Football Ecosystem: Competitive Intensity in the “Big Five”" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063097

APA StyleWagner, F., Preuss, H., & Könecke, T. (2021). A Central Element of Europe’s Football Ecosystem: Competitive Intensity in the “Big Five”. Sustainability, 13(6), 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063097