Greening the City: How to Get Rid of Garden Pavement! The ‘Steenbreek’ Program as a Dutch Example

Abstract

1. Introduction: Reduction of Green Surface in Cities

1.1. Pavement in Cities

1.2. The Role of Gardens in Cities for Wellbeing

1.3. Steenbreek and Steenbreek Alike Programs

2. Materials and Methods

3. Theory on Behavioral Change

3.1. Behavioral Change

3.2. The Behavioural Change Model

3.3. Factors That Can Be Influenced by External Programs

3.3.1. Predisposing Factors

Biological and Psychological Factors

Behavioural Factors

Physical-Environmental Factors

Social-Cultural Factors

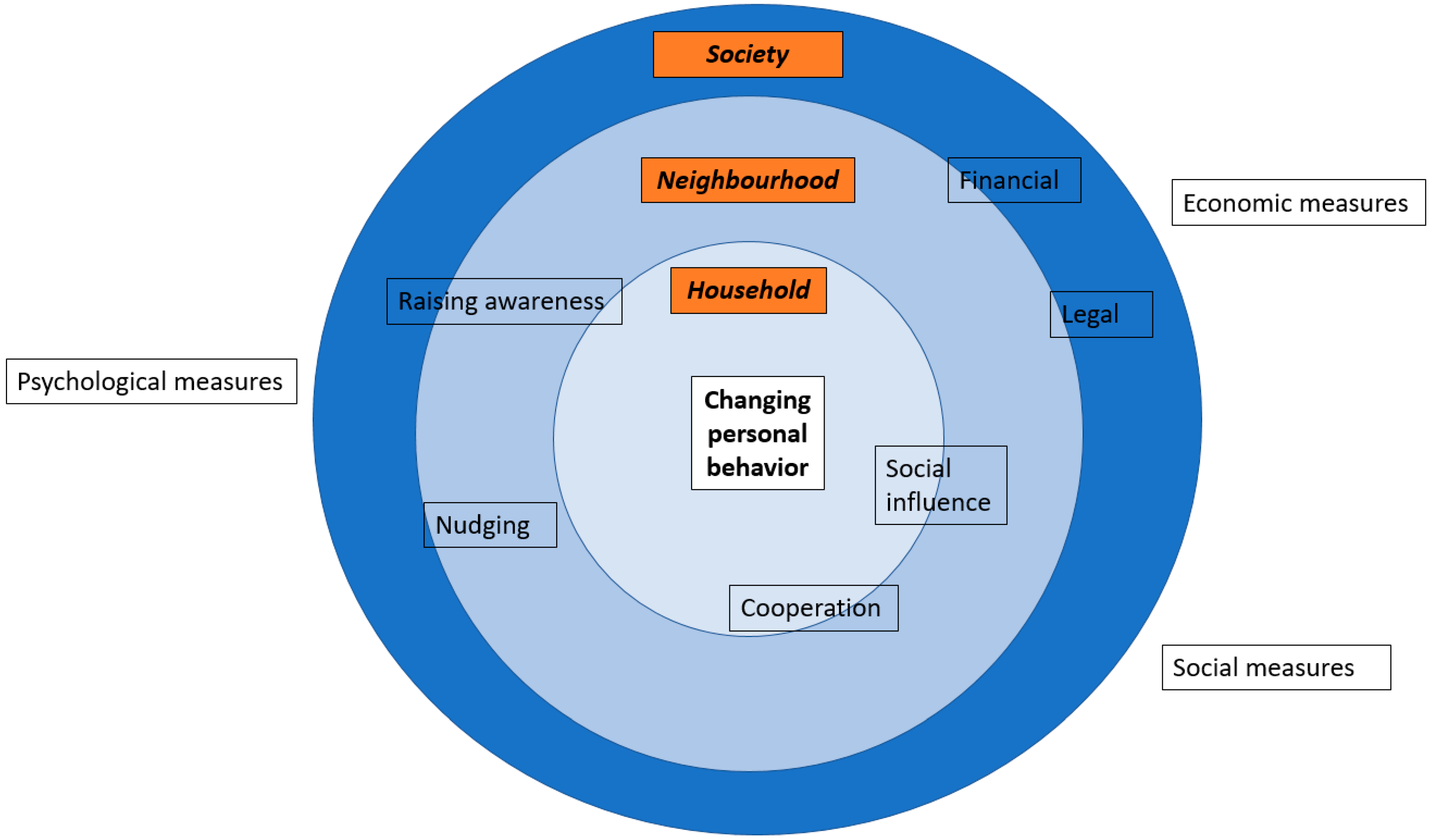

- Household: The most direct influence comes from members of the household. Consent must be reached within this group before a change in the appearance of the garden can take place (see Figure 1). All members of a household have needs and wishes. Children want to play (needs), and can have wishes influenced by what they see and hear at school (green school yards).

- Neighbours and other actors: There are two ways that the norms of neighbours can influence people: 1. Perceptions of what others are doing (descriptive norms) 2. What they think others expect them to do (injuctive norms) [45]. Descriptive norms for greening the city are: seeing others greening (or paving) their garden, which imposes a social norm for doing the same, thus suggesting a tipping point in greening or paving. Injunctive norms can inhibit or promote adaptation, depending on whether people believe that others approve or disapprove of this adaptation. However, Bouman and Steg [44] stated that individuals’ personal values are difficult to change and that individuals’ perceptions of others’ values might be more malleable. This is because perceptions of group values are based on limited and biased information, so the perceived group values often deviate from the real group values, also in the area of willingness to change. This suggests campaigning with information about the number of people that want to change (see also nudging). Van Valkengoed en Steg [45] stated that public participation may change perceived descriptive and injunctive norms related to adaptation. The work of a group of citizens can establish a descriptive norm that suggests to the general public that others are willing to engage in adaptation behaviour. Even people who are not actively participating themselves, but hear that different community members are involved in adaptation planning can be influenced.

- Municipalities: In addition to legislation, municipalities can influence the behaviour of inhabitants in two ways: by showing a good example and by cooperation. According to Van Valkengoed and Steg [45] there are six reasons why cooperation between municipalities and inhabitants can influence their behaviour (related to sustainability): 1. A two-way dialogue/conversation can help to determine each other’s responsibilities; 2. Jointly developed success-measurements for outcomes can increase the perception of inhabitants in relation to the effectiveness of the work carried out (to develop adaptation measures); 3. It can also raise perceived autonomy and empowerment of citizens, which can increase their personal motivation for undertaking further, individual adaptive measures; 4. It can increase trust in government and the perceived fairness of adaptation planning. Higher trust in government has been found to be positively, albeit weakly, associated with more engagement in private adaptation behaviour; 5. If citizens are actively involved in adaptation planning, changing behaviour may be perceived as part of a ‘citizens’ duty’ or a ‘community value’, which may strengthen people’s injunctive norm that adaptation is desirable and approved by members of the community; 6. It increases the effectiveness of communication strategies because the collaborating inhabitants become a source of (municipality) information. Through co-operation with local NGO’s municipalities can be more effective, because inhabitants will more easily accept a message from locals.

- Influencers: Just showing a vision directed at greening cities and showing moral sentiments about this, without even making regulations, is an incentive for (many) people to change behaviour. Zawadzki et al. [46] showed this for climate change, where the moral sentiments of political leaders predicted respondents’ willingness to save energy to reduce climate change and their support for the Paris Climate Agreement. In other words, politicians, and influential people in general, should provide a role model themselves and be explicit about the role that inhabitants can play in greening the gardens.

3.3.2. Information Factors

Channel

Source

Message

3.3.3. Ability Factors

Performance Skills

Implementation Plans

3.3.4. Supporting/Obstructing Factors

Barriers

Supporting Factors

Life Changing Events

3.4. Behavioural Change Factors That Cannot Be Influenced Directly by Programs

3.4.1. Awareness Factors

Knowledge

Cues to Action

Risks

3.4.2. Motivation Factors

Attitudes

Social Influence

Self-Efficacy

3.4.3. Intention State

3.4.4. Behavioural State

Experimenting/Trial

Maintaining

4. Results: Assessment of Steenbreek Initiatives in Terms of Behavioural Change

4.1. Influence of Steenbreek on Predisposing Factors

4.1.1. Biological and Psychological Factors

4.1.2. Physical-Environmental Factors

4.1.3. Social-Cultural Factors

4.2. The Use of Information Factors by Steenbreek

4.3. The Support for Ability Factors by Steenbreek

4.3.1. Implementation Plans

4.3.2. Performance Skills

4.4. Supporting/Obstructing Factors Removed by Steenbreek

4.4.1. Barriers

4.4.2. Life Changing Events

4.5. Learning from Additional Factors

4.6. Relevant Factors Related to Behavioral Change

4.6.1. Physical-Environmental Factors

4.6.2. Social-Cultural Factors

4.7. Applying the Garden Greening Behaviour Model to the Example Given Earlier

5. Discussion and Recommendations

5.1. Matching Theory with Practice

5.2. Actors and Measurements

- (1)

- Greening private gardens should be combined with greening the public space, to have a maximum effect on biodiversity [72], water retention, liveability, etc. Besides, a green public space can inspire people to green their garden too (physical-environmental factors). It shows that other actors like the municipality take their responsibility for greening seriously, which is also an important factor in behavioural change (social cultural factors).

- (2)

- All parties around the inhabitants should send the same message of greening the garden, and should show that they work together [73]. These parties include a municipality, water board, housing cooperation, but also neighbourhood organizations, garden centres and garden television programs.

- (3)

- Combining greening and social measures can have a positive impact. When the social measures lead to having a grip on ones’ own life (removing a barrier), it means that for some people more room for other issues like the garden enter their perspective. In particular when social projects lead to empowerment, this can also lead to larger ability factors to green the garden.

- (4)

- Besides raising awareness and softly influencing environmental behaviour, legal and financial measurements are also being deployed. In The Netherlands legal measures are not yet used, except by some housing corporations that demand that tenants make their gardens green again when leaving the house. One neighbourhood in Amsterdam [74] is very vulnerable for heat and flooding, so the municipality does not allow new pavement. However, there will be no direct enforcement, according to Beumer [30]. This can still be effective for a certain group of people who like to follow rules (‘hierarchists’). Examples from abroad (Germany, Belgium) give indications that a combination of financial, legal and exemption measures would be very helpful.

5.3. Freedom Dilemma

5.4. Recommendations

5.4.1. For Steenbreek

5.4.2. For Municipalities

5.4.3. For Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. 2019 Situation in Schiemond, Rotterdam

Appendix B. Overview Correlation Values

Appendix C. Survey Results

| 1. Which garden do you like best? | 2. Which garden does your garden most resemble? | |

| 1 paved garden | 7 (1.8%) | 37 (9.3%) |

| 2 well maintained garden | 118 (30%) | 126 (31.8%) |

| 3 ecological garden | 224 (56.9%) | 116 (29.3%) |

| 4 neglected garden | 45 (11.4%) | 61 (15.4%) |

| 5 do not have a garden | 56 (14.14%) |

| 1. Paved Garden | 2. Well Maintained Garden | 3. Ecological Garden | 4. Neglected Garden |

|  |  |  |

| 3. When would you be willing to make your garden more ecological? | |

| More knowledge | 151 |

| Financial support | 94 |

| My garden has already an ecological lay-out | 53 |

| I am not willing to do so | 53 |

| Other reasons | 46 |

References

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities and healthy societies. Urban Plan. 2017, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Uyttenhove, P.; Van Eetvelde, V. Planning green infrastructure to mitigate urban surface water flooding risk—A methodology to identify priority areas applied in the city of Ghent. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 194, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, F. Een Tuin is Een Aanval. De Groene Amsterdammer. 2020. Available online: https://www.groene.nl/artikel/een-tuin-is-een-aanval?utm_source=De%20Groene%20Amsterdammer&utm_campaign=bf2a323c39-Dagelijks-2020-05-07&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_853cea572a-bf2a323c39-70899937&fbclid=IwAR1rc0IgOUySfjpDrWRVnneRBGa7wPrlpAI8RFQVWdkz4L6jBlxh45vM6iQ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Van Heezik, Y.M.; Dickinson, K.J.M.; Freeman, C. Closing the gap: Communicating to change gardening practices in support of native biodiversity in urban private gardens. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberne, J.; Chardon, W.; Spijker, J.; Mol, G.; Van Hattum, T. Onttegel de tuin! Bewustwording over het belang van groene tuinen voor een klimaatbestendige stad. Bodem 2016, 5, 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Theeuwes, N.E.; Steeneveld, G.J.; Ronda, R.J.; Heusinkveld, B.G.; Holtslag, A.A.M. Mitigation of the urban heat island effect using vegetation and water bodies. In Proceedings of the ICUC8–8th International Conference on Urban Climates, Dublin Ireland, 6–10 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Steenbreek. Samen zorgen voor een groene, klimaatbestendige en gezonde leefomgeving. Available online: https://Steenbreek.nl (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Kullberg, J. Tussen Groen en Grijs. Een Verkenning van Tuinen en Tuinieren in Nederland; Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau: Haag, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C.; Dickinson, K.J.M.; Porter, S.; Van Heezik, Y. ‘My garden is an expression of me’. Exploring householders’ relationships with their gardens. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokop, G.; Jobstmann, H.; Schönbauer, A. Report on Best Practices for Limiting Soil Sealing and Mitigating Its Effects; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Subasi, I. In Deze Rotterdamse Buurt Liggen de Meeste Tegeltuinen. “Ik Schaam Me Ervoor”; Provinciaal Zeeuwse Courant: Zeeland, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.Y.H.; Jim, C.Y. Citizen attitude and expectation towards greenspace provision in compact urban milieu. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Hochuli, D.F. Defining greenspace: Multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Marty, T. MartyDoes ecological gardening increase species richness and aesthetic quality of a garden? Biol. Conserv. 2013, 159, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Egerer, M.H.; Ossola, A. Urban Gardens as a Space to Engender Biophilia: Evidence and Ways Forward. Front. Built Environ. 2018, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, K.L.; Freeman, C.N.; Sedon, P.J.; Stein, A.; Van Heezik, Y. A novel method for fine-scale biodiversity assessment and prediction across diverse urban landscapes reveals social deprivation-related inequalities in private, not public spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 151, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, R. Green in Neighbourhoods: Planning a Seed for the Future. The Role of Spatial Planning in Nature Provision for Children in Neighbourhood Project Development. Master’s Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, S.; Buijs, A.E.; Snep, R.P.H. Environmental Justice in The Netherlands: Presence and Quality of Greenspace Differ by Socioeconomic Status of Neighbourhoods. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, K.L.; Freeman, C.; Seddon, P.J.; Recio, M.R.; Stein, A.; Van Heezik, Y. The importance of urban gardens in supporting children’s biophilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 114, 201609588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suyin Chalmin-Pui, L.; Roe, J.; Griffiths, A.; Smyth, N.; Heaton, T.; Clayden, A.; Cameron, R. “It made me feel brighter in myself”—The health and well-being impacts of a residential front garden horticultural intervention. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grashof, A. Greening Private Gardens A Formative Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Steenbreek as a Steering Mechanism. Bachelor’s Thesis, University Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IVN Natuureducatie Groen Dichterbij. Groen Dichterbij. Available online: https://www.ivn.nl/groendichterbij (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Amsterdam Rainproof. Available online: https://www.rainproof.nl/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Meerbomennu. Available online: https://meerbomen.nu/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- CBS Open Data Statline Website Kerncijfers Wijken en Buurten 2019. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/84583NED/table?ts=1603880332061 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- SteenbreekCobra360.nl. Available online: https://steenbreek.cobra360.nl/index.php?@public (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Thaler, R.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, H.; Mudde, A.; Leijs, I.; Charlton, A.; Vartiainen, E.; Buijs, G.; Pais Clemente, M.; Storm, H.; Gonzales Navarro, A.; Nebot, M.; et al. The European Smoking Prevention Framework Approach (EFSA): An example of integral prevention. Health Educ. Res. 2003, 18, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, K.; Ooms, C.; Prins, L.; Syaifudin, A.; Verberne, J. Unharden the Garden. The Behavioural Choices and Motivations of Citizens in Relation to Soil Sealing; Report of an MSc Working Group; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beumer, C. Show me your garden and I will tell you how sustainable you are: Dutch citizens’ perspectives on conserving biodiversity and promoting a sustainable urban living environment through domestic gardening. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 30, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.L.; Masser, B.M.; Pachana, N.A. Exploring the health and wellbeing benefits of gardening for older adults. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatworthy, J.; Hinds, J.; Camic, P.M. Gardening as a mental health intervention: A review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2013, 18, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S.; Verheij, R.; Smeets, H. Groen en Gebruik ADHD-Medicatie Door Kinderen. De Relatie Tussen de Hoeveelheid Groen in de Woonomgeving en de Prevalentie van A(D)HD-Medicijngebruik bij 5- Tot 12-Jarigen; UR: Wageningen, The Netherlands; NIVEL: Utrecht, The Netherlands; UMC: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, S. Van Groen Naar Gezond: Mechanismen Achter de Relatie Groen–Welbevinden; Stand van Zaken en Kennisagenda. Alterra-Rapport 2714; Alterra Wageningen UR (University & Research Centre): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, K.L.; Casagrande, D.; Harlan, S.L.; Yabiku, S.T. Resident’s yard choices and rationales in a desert city: Social priorities, ecological impacts, and decision tradeoffs. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesling, F.M.; Manning, C.M. How green is your thumb? Environmental gardening identity an ecological gardening practices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptiste, A.P.; Foley, C.; Smardon, R. Understanding urban neighborhood differences in willingness to implement green infrastructure measures: A case study of Syracuse, NY. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A.; Prugsamatz, S. Habits as barriers to changing behaviour. Psykol. Tidsskr. 2012, 16, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H.; Van Knippenberg, A. Habit, information acquisition, and the process of making travel mode choices. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 27, 539–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heezik, Y.; Freeman, C.; Porter, S.; Dickinson, K.J.M. Garden Size, Householder Knowledge, and Socio-Economic Status Influence Plant and Bird Diversity at the Scale of Individual Gardens. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 1442–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, M.A.; Dougill, A.J.; Benton, T.G. Why garden for wildlife? Social and ecological drivers, motivations and barriers for biodiversity management in residential landscapes. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmyslony, J.; Gagnon, D. Residential management of urban front-yard landscape: A random process? Landsc. Urban Plan. 1998, 40, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzig, A.P.; Warren, P.; Martin, C.; Hope, C.; Katti, M. The effects of human socioeconomic status and cultural characteristics on urban patterns of biodiversity. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwman, T.; Steg, L. Engaging city residents in climate action: Addressing the personal and group value-base behind residents’ climate actions. Urbanisation 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L. Climate change adaptation by individuals and households: A psychological perspective. In Global Commission on Adaptation Background Paper; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzki, S.J.; Bouman, T.; Steg, L.; Bojarskich, V.; Druen, P.B. Translating climate beliefs into action in a changing political landscape. Clim. Chang. 2020, 161, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.J.; Howard, C.; Hedderley, D.; Shepherd, R. What Determines Trust in Information About Food-Related Risks? Underlying Psychological Constructs. Risk Anal. 1996, 16, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latré, E.; Perko, T.; Thijssen, P. Does It Matter Who Communicates? The Effect of Source Labels in Nuclear Pre-Crisis Communication in Televised News. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2018, 26, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chryssochoidis, G.; Strada, A.; Krystallis, A. Public trust in institutions and information sources regarding risk management and communication: Towards integrating extant knowledge. J. Risk Res. 2009, 12, 137–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Velde, L.; Verbeke, W.; Popp, M.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. The importance of message framing for providing information about sustainability and environmental aspects of energy. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 5541–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Comeau, L.A. Message framing influences perceived climate change competence, engagement, and behavioral intentions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.K.; Morales, N.A.; Chen, B.; Soodeen, R.; Moulton, M.P.; Jain, E. Love or Loss: Effective message framing to promote environmental conservation. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2019, 18, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, I.; Campillo, J. Increasing energy efficiency in low-income households through targeting awareness and behavioral change. Renew. Energy 2014, 67, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, S. From Grey to Green Gardens. Reasons for a Garden with a High Amount of Soil Sealing. Master’s Thesis, TU Delft & Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bottendaal.nl. Voor en Door Bottendaal Nijmegen. Available online: https://www.bottendaal.nl/tuintips-van-de-operatie-steenbreek-tuinadviseur/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Sijsenaar, A. Burgers Dragen een Steentje Weg Voor Water. Wat Kan de Gemeente Rotterdam doen om Burgers te Motiveren om een Bijdrage te Leveren aan de Klimaatopgave van de stad? Ph.D. Thesis, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, K.V. Thinking about learning: Implications for principle-based professional education. J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2002, 22, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiest, S.L.; Raymond, L.; Clawson, R.A. Framing, partisan predispositions, and public opinion on climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 31, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patuano, A. Biophobia and Urban Restorativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivos-Jara, P.; Segura-Fernández, R.; Rubio-Pérez, C.; Felipe-García, B. Biophilia and Biophobia as Emotional Attribution to Nature in Children of 5 Years Old. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aral, S.; Walker, D. Identifying Influential and Susceptible Members of Social Networks. Science 2012, 337, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, N.; Smit, H.; Burton, M. Place-Keeping: Open Space Management in Practice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IVN Natuureducatie. Train-de-trainerbijeenkomst: ‘Een levende tuin maak je zelf’. Available online: https://www.ivn.nl/activiteiten/train-de-trainerbijeenkomst-een-levende-tuin-maak-je-zelf (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Steenbreek. Margot Ribberink ambassadeur van Stichting Steenbreek. Available online: https://steenbreek.nl/margot-ribberink-ambassadeur-van-stichting-steenbreek/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Steenbreek. Tuinspreekuur met Lodewijk Hoekstra. Available online: https://steenbreek.nl/tuinspreekuur-met-lodewijk-hoekstra/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Duurzaam Den Haag. Available online: https://duurzaamdenhaag.nl/activiteiten/operatiesteenbreek (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Steenbreek. Bluumkes feur jou! Available online: https://steenbreek.nl/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/gw201112_074000_steenbreek_ok-lr-2.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Youtube. GoudGroen. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL_L9M4XuclKSNWvW8BLxpQ_gL7X-SgM31 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Straver, F. Moeilijk? Nee hoor! Waarom Iedereen Volgens Raymond Landegent (34) nu Meteen een Geveltuin Moet Aanleggen. Duurzame 100: 1000 Geveltuinen. Dagblad Trouw. 9 October 2020. Available online: https://www.trouw.nl/duurzaamheid-natuur/moeilijk-nee-hoor-waarom-iedereen-volgens-raymond-landegent-34-nu-meteen-een-geveltuin-moet-aanleggen~bc7f13a8/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Stichting De Groene Apotheek. Help mee om deze kinderen onder de aandacht te brengen !! Voor alle informatie , klik op bovenstaande link !! Help mee !! Available online: https://www.stichtingdegroeneapotheek.nl/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Palm, R.; Bolsen, T.; Kingsland, J.T. ‘Don’t Tell Me What to Do’: Resistance to Climate Change Messages Suggesting Behavior Changes. Weather Clim. Soc. 2020, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, M.F.J.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S.; Nilon, C.H.; Vargo, T. Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobbelaar, D.J. Impact of Student Interventions on Urban Greening Processes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedegebuure, J. Tuinen in Kwetsbare Wijk Amsterdam Mogen Maar Voor Helft uit Tegels Bestaan. Algemeen Dagblad. 26 February 2020. Available online: https://www.ad.nl/wonen/tuinen-in-kwetsbare-wijk-amsterdam-mogen-maar-voor-helft-uit-tegels-bestaan~a0d95803/ (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Haignere, C.S. Closing the ecological gap: The public/private dilemma. Health Educ. Res. 1999, 14, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ter Meulen, R. Solidarity and Justice in Health Care. A Critical Analysis of their Relationship. Diametros 2015, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, G.C. The responsibilization strategy of health and safety. Neo-liberalism and the reconfiguration of individual responsibility for risk. Br. J. Criminol. 2009, 49, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, B.; Elisabeth, B.G. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and It Social and Political Consequences; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt-Martinez, K.; Donnelly, K.A.; Laitner, J.A. Advanced Metering Initiatives and Residential Feedback Programs: A Meta-Review for Household Electricity-Saving Opportunities; American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C.; Rothengatter, T. The effect of tailored information, goal setting, and tailored feedback on household energy use, energy-related behaviors, and behavioral antecedents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.S.; Niemiec, R.M. Social-psychological correlates of personal-sphere and diffusion behavior for wildscape gardening. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, M.A.; Dougill, A.J.; Benton, T.G. Scaling up from gardens: Biodiversity conservation in urban environments. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 25, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shwartz, A.; Turbé, A.; Julliard, R.; Simon, L.; Prévot, A.C. Outstanding challenges for urban conservation research and action. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 28, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Sub-Factor | Within Sample | Other Examples | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predisposing: Biological and psychological | - | +/- | Biological and psychological effects of a green garden are underexposed | |

| Predisposing: Physical and environmental | + | + | Many projects aiming to green the public space surrounding gardens | |

| Predisposing: Social cultural | influencers | - | +/- | Influencers are used on national level |

| Neighbours and other actors | + | + | Much emphasis on ‘together’ | |

| households | +/- | +/- | Difficult to reach, probably via children/school projects | |

| Information | Two-way process | +/- | +/- | Awareness is available, implementation of two-way process in some initiatives |

| Using other sources | + | + | In implementation and spreading the message | |

| Message | +/- | +/- | Clear message, could be more tailored to the private social ecological situation | |

| Channel | + | + | Many types of channels are used | |

| Ability factors | Implementation plan | +/- | +/- | Good examples but not used everywhere |

| Performance skills | + | + | Many ways to improve performance skills | |

| Supporting/obstructing | Barriers | +/- | +/- | Some of the six identified barriers are always addressed (money, plants), some not so often (language, more urgent problems, time) |

| Life change | - | +/- | Some strong examples, that could be used more widely | |

| Additional factors | Cues to action (awareness) | - | +/- | No interventions after a hazard. |

| Habits | +/- | +/- | No awareness yet, except for Bluumkes feur jou | |

| Knowledge (awareness) | +/- | +/- | Some joint effort for spreading the message | |

| Efficacy (motivation) | - | - | Being more precise about the effect of private actions | |

| Intentional state | - | - | Initiatives could be much more focused on the contemplation state | |

| Experiment (behaviour) | - | + | Small interventions for greening the garden are often carried out | |

| Maintenance (behaviour) | - | - | No examples of coaching in maintenance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stobbelaar, D.J.; van der Knaap, W.; Spijker, J. Greening the City: How to Get Rid of Garden Pavement! The ‘Steenbreek’ Program as a Dutch Example. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063117

Stobbelaar DJ, van der Knaap W, Spijker J. Greening the City: How to Get Rid of Garden Pavement! The ‘Steenbreek’ Program as a Dutch Example. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063117

Chicago/Turabian StyleStobbelaar, Derk Jan, Wim van der Knaap, and Joop Spijker. 2021. "Greening the City: How to Get Rid of Garden Pavement! The ‘Steenbreek’ Program as a Dutch Example" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063117

APA StyleStobbelaar, D. J., van der Knaap, W., & Spijker, J. (2021). Greening the City: How to Get Rid of Garden Pavement! The ‘Steenbreek’ Program as a Dutch Example. Sustainability, 13(6), 3117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063117