Perspective on COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Impacting Organizational Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Authentic Leadership

2.2. COVID-19-Influenced Time

2.3. Trust

2.4. Communal Relationships

2.5. Social Exchange Relationships

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Sampling

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Factor Loading Analysis

3.4. Research Model and Hypothesis

3.4.1. Trust and Communal Relationships

3.4.2. Trust and Leadership in Organizations

3.4.3. Trust and Social Exchange Relationships

3.4.4. Communal Relationships and Leadership in Organizations

3.4.5. Social Exchange Relationships and Leadership in Organizations

4. Results

4.1. Data Analysis

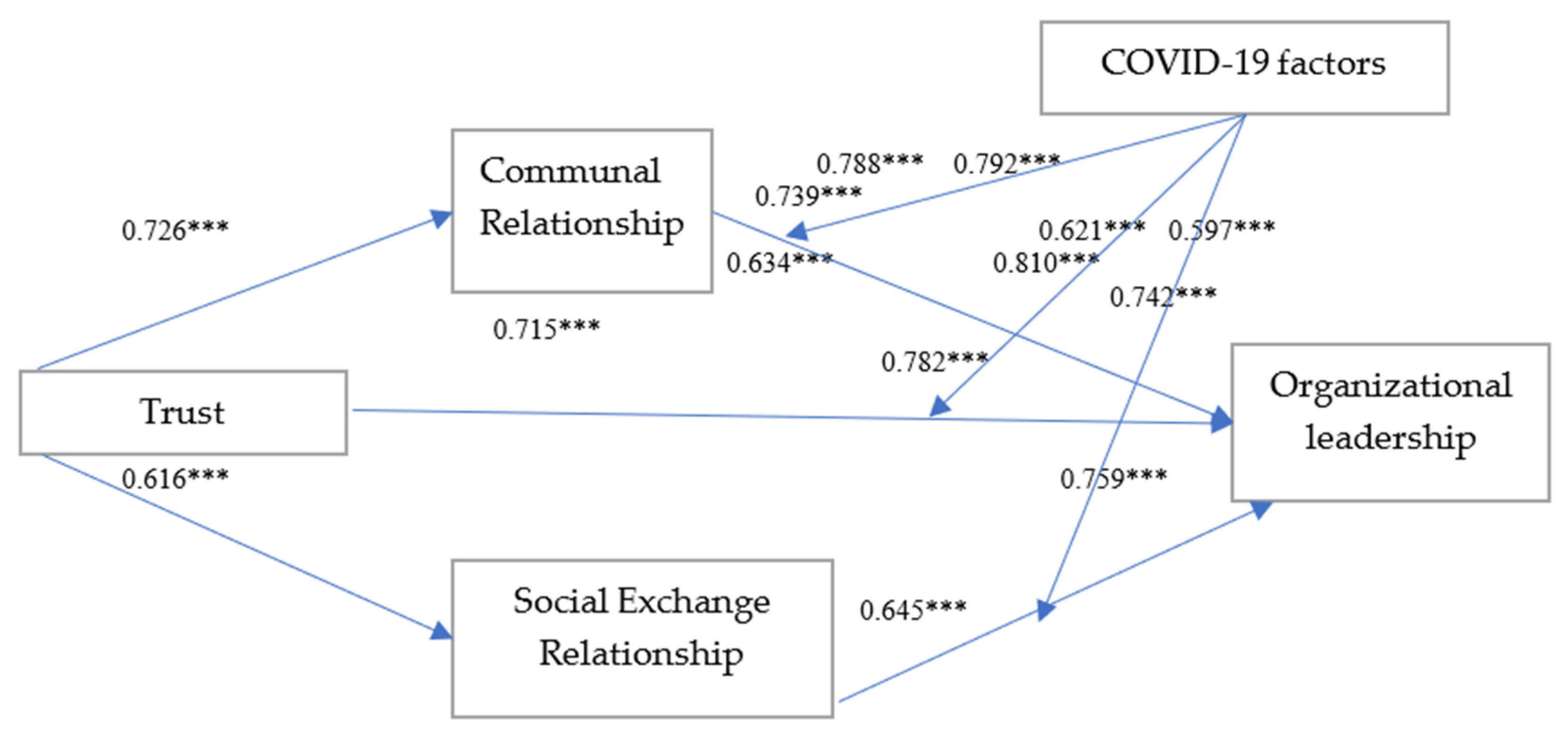

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Perspective the Results of Moderating Effect of Hypothesis Test

4.3.1. Hypotheses without COVID-19 Factors

4.3.2. Hypotheses with COVID-19 Factors

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Discussion with COVID-19 Factors

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications of COVID-19 Case

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. COVID-19 Factors Details

| COVID-19 (F1) Factors | COVID-19 (F2) Factors | COVID-19 (F3) Factors |

| (1) Leader were able to handle change efficiently during the pandemic. (LO13) (2) Leaders supported staff fairly (morally). (LO14) (3) Leaders listened to staffs’ opinions and comments. (LO15) (4) Leaders built the staffs’ confidence through empathy, support, and reassurance during the pandemic. (LO16) (5) Infected staff received more care from leaders. (SER9) (6) Leaders were able to meet expectations of staff, so that staffs could remain productive and healty during the pandemic. (SER10) (7) Leaders boosted staffs’ motivation by providing support. (SER12) (8) Leaders took care of staff in organizations during the pandemic. (CR6) | (1) Staff trusted leders more by their actions than their words. (Trust1) (2) Leaders had good and clear communication with staff frequently during COVID-19. (Trust2) (3) Staff was able to rely on leaders during the pandemic. (Trust3) (4) Everyone believed that solidarity was key toward true collaboration during the pandemic. (Trust4) (5) Staff followed the leaders like one would follow a family leader during the pandemic. (CR5) (6) Leaders were concerned about their staffs’ well-being during the pandemic. (CR7) | (1) Remotely working staff interacted intimately with coworkers from their home online. (CR8) (2) Leaders and increased interdependence by online during the pandemic. (SER11) |

References

- Staniškienė, E.; Stankevičiūtė, Ž. Social sustainability measurement framework: The case of employee perspective in a CSR-committed organisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 188, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. Building Sustainable Organizations: The Human Factor. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and performance: Still searching for some answers. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2011, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Data Coronavirus Executive Briefing—Business.att.com. n.d. Available online: https://www.business.att.com/content/dam/attbusiness/briefs/att-globaldata-coronavirus-executive-briefing.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Deloitte, US. Leadership Beyond the Crisis. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/de/Documents/human-capital-consulting/COVID19_Leadership_Styles.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Fernandez, A.A.; Shaw, G.P. Academic Leadership in a Time of Crisis: The Coronavirus and COVID-19. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2020, 14, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON. What COVID-19 Teaches Us about the Importance of Trust at Work. Available online: https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/covid-19-teaches-us-importance-trust-work (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Trimble, A. The Impact of Covid-19 on Working Relationships. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/blog/2020/05/impact-covid-19-working-relationships (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Hsieh, C.-C.; Wang, D.-S. Does supervisor-perceived authentic leadership influence employee work engagement through employee-perceived authentic leadership and employee trust? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2329–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Christensen, A.L.; Hailey, F. Authentic leadership and the knowledge economy. Organ. Dyn. 2011, 40, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyns, M.; Rothmann, S. Dimensionality of trust: An analysis of the relations between propensity, trustworthiness and trust. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2015, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, R.; Sinha, S.; Tiwari, V. Crucial Factors of Human Resource Management for Good Employee Relations: A Case Study. Int. J. Min. Metall. Mech. Eng. 2013, 1, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, S.; Farid, T.; Jianhong, M.; Mehmood, Q. Cultivating employees’ communal relationship and organizational citizenship behavior through authentic leadership: Studying the influence of procedural justice. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 11, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, E. Importance of Positive Relationships in Workplace. Available online: https://positivepsychology.com/positive-relationships-workplace/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Hon, L.C.; Grunig, J.E. Guidelines for Measuring Relationships in Public Relations; The Institute for Public Relations, Commission on PR Measurement and Evaluation: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, L.M.; Tetrick, L.E.; Lynch, P.; Barksdale, K. Social and economic exchange: Construct development and validation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 837–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, H.H.; Dasborough, M.T.; Ashkanasy, N.M. A multi-level analysis of team climate and interpersonal exchange relationships at work. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.W.; Grimm, P.E. Communal and exchange relationship perceptions as separate constructs and their role in motivations to donate. J. Consum. Psychol. 2010, 20, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. The Interactive Effect of Authentic Leadership and Leader Competency on Followers’ Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement. J. Bus. Ethic 2016, 153, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Avolio, B.J.; Luthans, F.; May, D.R.; Walumbwa, F. “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 343–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic Leadership: Development and Validation of a Theory-Based Measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Morgeson, F.P.; Nahrgang, J.D. Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader–follower outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 2005, 16, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmett, J.; Schrah, G.; Schrimper, M.; Wood, A. COVID-19 and the Employee Experience: How Leaders Can Seize the Moment. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/covid-19-and-the-employee-experience-how-leaders-can-seize-the-moment (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Edmondson, A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relationships, A. Employer-Employee Relations Grow Stronger, even Amid COVID-19 Job Losses: Study. Available online: https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/employer-employee-relations-grow-stronger-even-amid-covid-19-job-losses-study-840741385.html (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Dolan, L.S.; Raich, M.; Garti, A.; Landau, A. The COVID-19 Crisis as an Opportunity for Introspection: A Multi-Level Reflection on Values, Needs, Trust and Leadership in the Future. Available online: https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/the-covid-19-crisis-as-an-opportunity-for-introspection/ (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Carrington, D.J.; Combe, I.A.; Mumford, M.D. Cognitive shifts within leader and follower teams: Where consensus develops in mental models during an organizational crisis. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Associaion. How Leaders Can Maximize Trust and Minimize Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/apa/2020/03/covid-19-leadership.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Wong, E.S.; Then, D.; Skitmore, M. Antecedents of trust in intra-organizational relationships within three Singapore public sector construction project management agencies. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Meng, X. The role of trust in relationship development and performance improvement. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2015, 21, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Mishra, K.E. The research on trust in leadership: The need for context. J. Trust. Res. 2013, 3, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcallister, D.J. Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, A.; Glińska-Neweś, A.; Kalińska, M. The role of leadership in shaping interpersonal relationships in the context of positive organizational potential. J. Posit. Manag. 2015, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ballinger, G.A.; Schoorman, F.D.; Lehman, D.W. Will you trust your new boss? The role of affective reactions to leadership succession. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Oullette, R.; Powell, M.C.; Milberg, S. Recipient’s mood, relationship type, and helping. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunaetz, D.R. A Missionary’s Relationship to Sending Churches: Communal and Exchange Dimensions. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Mils, J. The Difference between Communal and Exchange Relationships: What it is and is not. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 19, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Mills, J. Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1979, 37, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Clark, M.S.; Ford, T.E.; Johnson, M. Measurement of communal strength. Pers. Relatsh. 2004, 11, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hui, C.-M. The Roles of Communal Motivation in Daily Prosocial Behaviors: A Dyadic Experience-Sampling Study. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2019, 10, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tnay, E.; Othman, A.E.A.; Siong, H.C.; Lim, S.L.O. The Influences of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment on Turnover Intention. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 97, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Grayson, K. Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, G.R.; Wang, P.Z.; Kyngdon, A.S. Conceptualizing and modeling interpersonal trust in exchange relationships: The effects of incomplete model specification. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 76, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, B.A.; Elfring, T. How Does Trust Affect the Performance of Ongoing Teams? The Mediating Role of Reflexivity, Monitoring, and Effort. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, B.A.; Dirks, K.T.; Gillespie, N. Trust and team performance: A meta-analysis of main effects, moderators, and covariates. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirks, K.T. Trust in leadership and team performance: Evidence from NCAA basketball. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Rowlinson, S. Interpersonal trust and inter-firm trust in construction projects. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2009, 27, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Farid, T.; Khan, M.K.; Zhang, Q.; Khattak, A.; Ma, J. Bridging the Gap between Authentic Leadership and Employees Communal Relationships through Trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.; Lecavalier, L. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Developmental Disability Psychological Research. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; Maccallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephanie, G. Correlation Coefficient: Simple Definition, Formula, Easy Calculation Steps. Available online: https://www.statisticshowto.com/probability-and-statistics/correlation-coefficient-formula/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Kaul, V.; Shah, V.H.; El-Serag, H. Leadership During Crisis: Lessons and Applications from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 809–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Wieselquist, J.; Foster, C.A.; Witcher, B.S. Commitment and Trust in Close Relationships an Interdependence Analysis. In Handbook of Interpersonal Commitment and Relationship Stability; Kluwer Academic/Plenum: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 427–449. [Google Scholar]

- Communal Relationships—IResearchNet. Available online: http://psychology.iresearchnet.com/social-psychology/interpersonal-relationships/communal-relationships/ (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- Williamson, G.M.; Clark, M.S. The communal/exchange distinction and some implications for understanding justice in families. Soc. Justice Res. 1989, 3, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.J.E.; Rempel, J.K. Trust and Partner-Enhancing Attributions in Close Relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.L.; Holmes, J.G. Motivating Responsiveness: Five Elements to Relationship Know-How. In Interdependent Minds: The Dynamics of Close Relationships; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, K.R.; Alibhai, A.; Boon, S.D.; Ellard, J.H. Trust as an Explanation for Relational Differences in Revenge. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 38, 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, K. Guidelines for Measuring Trust in Organizations (Updated). Available online: https://instituteforpr.org/guidelines-for-measuring-trust-in-organizations-2/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Konovsky, M.A.; Pugh, S.D. CITIZENSHIP BEHAVIOR AND SOCIAL EXCHANGE. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druskat, V.U.; Wheeler, J.V. Managing from the Boundary: The Effective Leadership of Self-managing Work Teams. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Dooley, L.M.; Zhang, R. The effects of authentic leadership on trust in leaders, organizational citizenship behavior, and service quality in the Chinese hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxen, L.; Van Der Vaart, L.; Stander, M.W. Authentic leadership and organisational citizenship behaviour in the public health care sector: The role of workplace trust. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2016, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stander, F.W.; De Beer, L.T.; Stander, M.W. Authentic leadership as a source of optimism, trust in the organisation and work engagement in the public health care sector. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; Lepine, J.A. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuer, C.; Hüffmeier, J.; Hertel, G. Does trust matter more in virtual teams? A meta-analysis of trust and team effectiveness considering virtuality and documentation as moderators. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Werner, J.M. Managers as Initiators of Trust: An Exchange Relationship Framework for Understanding Managerial Trustworthy Behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J.B.; Walker, H.J. Propensity to Trust and the Impact on Social Exchange. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Van Knippenberg, D. Gender and leadership aspiration: The impact of organizational identification. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 1018–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Farid, T.; Jianhong, M.; Khattak, A.; Nurunnabi, M. The Impact of Authentic Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behaviours and the Mediating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Banking Sector of Pakistan. Sustain. J. Rec. 2018, 10, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benge, M. Assessing the Relationship between Supervisors and Employees. EDIS 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.S.; Armentano, A.L.; Boothby, E.J.; Hirsch, J.L. Communal relational context (or lack thereof) shapes emotional lives. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, A.P. The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychol. Rev. 1992, 99, 689–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkie, R. Trust in leadership is vital for employee performance. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldkirch, M.; Nordqvist, M.; Melin, L. CEO turnover in family firms: How social exchange relationships influence whether a non-family CEO stays or leaves. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.A. Five Steps to Leading Your Team in the Virtual COVID-19 Workplace. Organ. Dyn. 2020, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F. Ethical leadership in sustainable organizations: The moderating role of general self-efficacy and the mediating role of organizational trust. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 22, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasel, M.C. A question of context: The influence of trust on leadership effectiveness during crisis. Management 2013, 16, 264–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandura, T.A.; Pellegrini, E.K. Trust and Leader—Member Exchange. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 15, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrasher, G.R.; Biermeier-Hanson, B.; Dickson, M.W. Getting Old at the Top: The Role of Agentic and Communal Orientations in the Relationship Between Age and Follower Perceptions of Leadership Behaviors and Outcomes. Work. Aging Retire. 2019, 6, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coan, J.A.; Schaefer, H.S.; Davidson, R.J. Lending a Hand. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.; Baykal, E.; Abid, G. E-Leadership and Teleworking in Times of COVID-19 and Beyond: What We Know and Where do We Go. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, R.M.; Johnston, W.J. The Coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: Crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 88, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Oh, H. Business-to-business social exchange relationship beyond trust and commitment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 65, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Cooper, B.; Sendjaya, S. How Servant Leadership Influences Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Roles of LMX, Empowerment, and Proactive Personality. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 145, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Nasim, A.; Khan, S.A.R. A moderated-mediation analysis of psychological empowerment: Sustainable leadership and sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Frequencies | Sample Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Respondent Age | ||

| Less than 30 years | 17 | 7.7 |

| 30–35 years | 29 | 13.2 |

| 36–40 years | 49 | 22.3 |

| 41–45 years | 34 | 15.5 |

| 46–50 years | 28 | 12.7 |

| 51–55 years | 22 | 10 |

| 56–60 years | 14 | 6.4 |

| 0ver 60 | 27 | 12.3 |

| Respondent Gender | ||

| Male | 102 | 46.4 |

| Female | 118 | 53.6 |

| Respondent Position | ||

| Basic Manager | 97 | 44.1 |

| Middle Manager | 52 | 23.6 |

| High Manager | 71 | 32.3 |

| Respondent Years of Experience in the Company | ||

| 5 years | 53 | 24.1 |

| 6–10 years | 49 | 22.3 |

| 11–15 years | 49 | 22.3 |

| 16–20 years | 19 | 8.6 |

| Over 20 years | 50 | 22.7 |

| Respondent Work Experience as a Manager | ||

| Less than 5 years | 67 | 30.5 |

| 5–10 years | 77 | 35 |

| 11–15 years | 29 | 13.2 |

| 16–20 years | 19 | 8.6 |

| Over 20 years | 28 | 12.7 |

| The type of Company | ||

| Manufacturing/Factory | 52 | 23.6 |

| Wholesale Business | 24 | 10.9 |

| Retail Business | 25 | 11.4 |

| Service Business | 119 | 54.1 |

| Number of Employees in Respondent Company | ||

| Fewer than 10 employees | 86 | 39.1 |

| 10–49 employees | 84 | 38.2 |

| 50–249 employees | 23 | 10.5 |

| 250 employees or more than people | 27 | 12.3 |

| Company Annual Revenue | ||

| Not over USD10 million | 177 | 80.5 |

| USD10 million- USD1 billion | 38 | 17.3 |

| Over USD 1 billion | 5 | 2.3 |

| Total Respondents | 220 | 100 |

| Component | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | |

| Covid-19 LO (16) | 0.754 | ||

| Covid-19 SER (10) | 0.751 | ||

| Covid-19 LO (15) | 0.681 | ||

| Covid-19 LO (13) | 0.654 | ||

| Covid-19 SER (9) | 0.639 | ||

| Covid-19 SER (12) | 0.622 | ||

| Covid-19 LO (14) | 0.614 | ||

| Covid-19 CR (6) | 0.514 | ||

| Covid-19 Trust (4) | 0.771 | ||

| Covid-19 Trust (2) | 0.747 | ||

| Covid-19 Trust (1) | 0.739 | ||

| Covid-19 Trust (3) | 0.737 | ||

| Covid-19 CR (5) | 0.625 | ||

| Covid-19 CR (7) | 0.567 | ||

| Covid-19 CR (8) | 0.831 | ||

| Covid-19 SER (11) | 0.770 |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation | Variable | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 3.7945 | 0.70689 | COVID-19 (F1)_CR | 3.7776 | 0.65790 |

| CR | 3.7625 | 0.73023 | COVID-19 (F2)_CR | 3.7498 | 0.69150 |

| SER | 3.8602 | 0.69082 | COVID-19 (F3)_CR | 3.6631 | 0.72409 |

| LO | 3.8011 | 0.76335 | COVID-19 (F1)_SER | 3.8264 | 0.63514 |

| COVID-19 (F1)_trust | 3.7936 | 0.64072 | COVID-19 (F2)_SER | 3.7987 | 0.65993 |

| COVID-19 (F2)_trust | 3.7658 | 0.65506 | COVID-19 (F3)_SER | 3.7119 | 0.69122 |

| COVID-19 (F3)_trust | 3.6791 | 0.71201 |

| Relationship of Variables | Beta Value | p-Value | Hypothesis Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| trust ↔ CR | 0.726 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H1 |

| trust ↔ SER | 0.616 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H3 |

| trust ↔ LO | 0.715 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H2 |

| COVID-19 (F1)_trust ↔ LO | 0.782 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H2a |

| COVID-19 (F2)_trust ↔ LO | 0.810 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H2b |

| COVID-19 (F3)_trust ↔ LO | 0.621 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H2c |

| CR ↔ LO | 0.739 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H4 |

| COVID-19 (F1)_CR ↔ LO | 0.788 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H4a |

| COVID-19 (F2)_CR ↔ LO | 0.792 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H4b |

| COVID-19 (F3)_CR ↔ LO | 0.634 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H4c |

| SER ↔ LO | 0.645 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H5 |

| COVID-19 (F1)_SER ↔ LO | 0.742 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H5a |

| COVID-19 (F2)_SER ↔ LO | 0.759 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H5b |

| COVID-19 (F3)_SER ↔ LO | 0.597 *** | p < 0.001 | Accept H5c |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.K.C.; Sriphon, T. Perspective on COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Impacting Organizational Leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063230

Chen JKC, Sriphon T. Perspective on COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Impacting Organizational Leadership. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063230

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, James K. C., and Thitima Sriphon. 2021. "Perspective on COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Impacting Organizational Leadership" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063230

APA StyleChen, J. K. C., & Sriphon, T. (2021). Perspective on COVID-19 Pandemic Factors Impacting Organizational Leadership. Sustainability, 13(6), 3230. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063230