1. Introduction

By 2050, it is estimated that total global population will reach 9.7 billion, 68% projected to live in urban areas [

1,

2]. Along the rapid urbanization process and population growth, global challenges like climate change and public health emergencies have exaggerated the risks of sustainable urban food supply potentially leading to serious social problems if not properly dealt with. In the past few decades, urban agriculture is gaining increasing attentions in academia and policy agenda, recognized as a valuable contributor to meet the food and nutrition demand of urban dwellers while also bringing positive impacts to local economics, environment, social equity and culture preservation.

A widely accepted definition of urban agriculture is by Mougeot [

3], recognizing urban agriculture as “an industry located within (intra-urban) or on the fringe (peri-urban) of a town, a city or a metropolis, which grows and raises, processes and distributes a diversity of food and non-food products, (re-) using largely human and material resources, products and services found in and around that urban area, and in turn supplying human and material resources, products and services largely to that urban area.” Nevertheless, the features of urban agriculture are very dependent on the local context, varying dramatically worldwide. In developing countries, urban agriculture is usually practiced by the urban poor households for basic subsistence, to reduce food and nutrition insecurity and save food expenses [

4]. In contrast, practitioners in more developed countries often undertake urban agriculture for its multiple functions that lead to higher life quality, such as to build better connections of communities and to improve green infrastructures in urban centers. Novel production systems that are high-yield, space-saving, and environmentally-friendly are also observed there, to explore innovative ways to feed urban centers with locally produced food [

5].

Classification of urban agriculture can be based on a range of factors such as location, scale, objective, ownership and so on [

6]. Among the many categorizing criteria, differentiation of intra-urban and peri-urban agriculture has been commonly mentioned. A general distinction of the two is the location, with intra-urban agriculture located in densely settled areas, normally called “urban agriculture” for short, while peri-urban agriculture is located in the urban periphery, normally considered as a transition zone between urban and rural areas. Starting from this, other distinct features in farming and business models are also observed between urban and peri-urban agriculture. For example, peri-urban agriculture is often expected to have higher yields of food production due to the higher availability of space and level of farming professionalism as compared to urban agriculture [

7]. In addition, urban agriculture is mostly practiced through self-motivation with the food for self-consumption or donations, while peri-urban agriculture is more profit-oriented implementing diverse business models [

8,

9,

10]. Multifunctional activities and diversification approaches are typical in peri-urban agriculture due to an increasing urban demand for the goods and services provided by peri-urban areas, which has indeed facilitated the urban-rural relationship and recognized as a tool for rural development [

11].

In China, although no golden-rule definition of urban agriculture is existing at this early exploration stage, it is generally considered that urban agriculture is an advanced form of agriculture transformed from traditional agriculture and modern agriculture, which is correspondent to a high level of urbanization and development stage of the region. Specifically, traditional agriculture focuses on basic production activities mainly for subsistence, carried out by small farmers with limited capacity in production and management. Modern agriculture, in the context of China, featuring intensive production and large-scale commercialization with more advanced technologies and higher value addition along the food chain. Urban agriculture, often called urban modern agriculture in China, takes place in urban and surrounding areas and serves more sustainable lifestyle of city dwellers through supplying fresh healthy food and multi-dimension values such as in leisure, sightseeing and spiritual experiences.

To this end, urban agriculture in China started to appear on the agenda of large central cities in the past few decades as a tool to achieve modernization of agriculture and city high-quality development goals. Beijing released the Guide on Accelerating the Development of Urban Modern Agriculture in 2005, with subsequent policies and planning introduced since then [

12]. In Shanghai, the Ninth Five-Year Plan of Economic and Social Development and Vision for 2010 document claimed to explore various functions of urban modern agriculture in 1996, indicating the first important political impetus for urban agriculture development in Shanghai [

13]. Guangzhou pointed out to optimize agricultural industry structure through urban modern agriculture in 2010. To facilitate the development of urban modern agriculture, an evaluation system of agricultural park was set up by the municipal government in 2020 [

14]. In Chengdu, urban agriculture practices started since the last century and gradually attract political attentions since then, which will be detailed in

Section 3.

Along with the increasing wills and goals with respect to urban agriculture, fundamental research to characterize, measure and analyze its impacts and potentials become ever more important for comprehensive understanding and strategy designing for the urban agriculture industry. Relevant studies are emerging in recent years, focusing on various aspects of urban agriculture. Many of them limited the scope of urban agriculture within a form of modern agriculture, thus assessing urban agriculture only from the economic perspective on the production abilities and cost-benefit patterns [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Some studies specifically evaluated the environmental impacts of urban agriculture using the Pressure-Stress-Response model or Life Cycle Assessment measures [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Other studies assessed the multiple functions and contributions of urban agriculture in city development [

26,

27]. However, neither have the existing studies presented any information on China’s western cities like Chengdu which is indeed worth researching as a model city, nor has a holistic evaluation framework been developed that assesses the capacities, practices and potentials of all aspects of urban agriculture in a given city. To fill this gap, the present study first conducted a broad assessment of urban agriculture in Chengdu, providing a primary urban agriculture profile of the city. Then a comprehensive evaluation framework was developed, which features a systemic tool for in-depth assessment and monitoring of local urban agriculture and for potential adapted use in other Chinese cities.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of the Scope

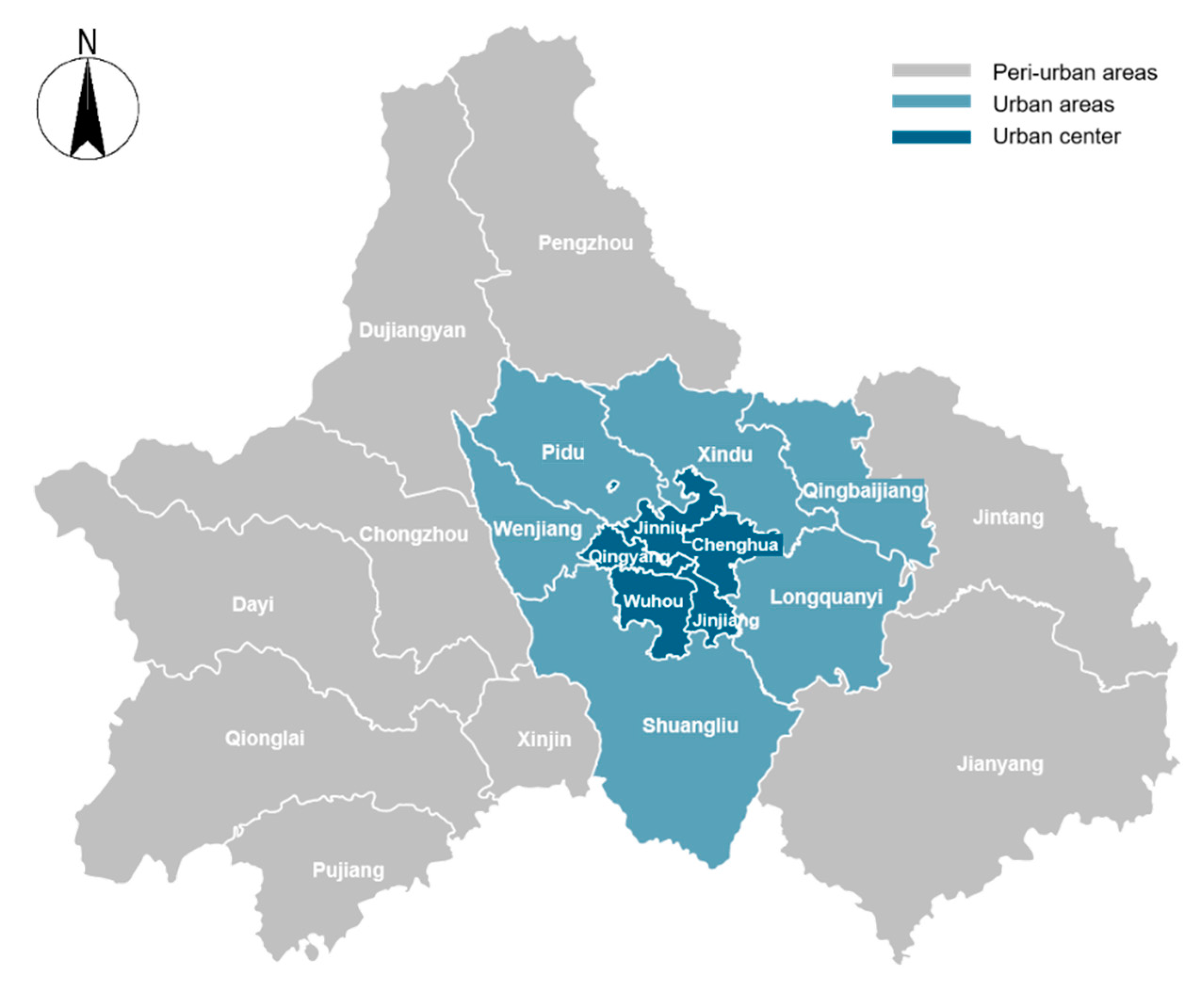

There are more than 16 million people living in Chengdu to be fed by the city’s food systems [

28]. This indicates a significant role agriculture is supposed to play to ensure sustainable and resilient food supply of the city, requiring farseeing food planning and resource allocation. Given the main objective of the assessment is to support urban planners and city authorities to better plan for the city’s food systems and facilitate the high-quality development vision of the city, the spatial scope of this assessment was determined within the administrative boundary of Chengdu City. The total area is 14,335 square kilometer (km

2), encompassing 12 districts in urban areas, five city-level counties, and four counties in peri-urban areas (

Figure 1).

Thematically, the assessment exercise covers (1) the developing history of urban agriculture in Chengdu that provides insights on the foundation and environment of urban agriculture activities; (2) available resources for urban agriculture that indicates the capacity to develop urban agriculture locally; (3) urban agriculture practices that reveal the current status and performance and that suggest future impacts and contributions; and (4) opportunities and challenges that shed light on the potentials and directions of actions. Building on these assessments, five themes were identified as key aspects of urban agriculture in Chengdu, for which a systemic tool was developed to assist further in-depth assessment. In the end, a pilot in-depth assessment on the five determined urban agriculture themes was carried out, providing a useful example for precise measuring and monitoring urban agriculture in Chinese cities, which supports food planning in the long run.

3.2. History and Foundation

In parallel with the increase of the urbanization rate as shown in

Figure 2, the development of urban agriculture in Chengdu is generally divided into four phases [

31] (

Table 2):

The first phase commenced since the full implementation of the Household Contract Responsibility System in Chengdu in 1983, which has greatly motivated farmers and improved agricultural production. The municipal government also gradually realized the crucial role of peri-urban agriculture in the supply of fresh food, bringing the incentive to develop peri-urban agriculture. In 1989 and 1995, respectively, the two rounds of Shopping Basket Program have facilitated the development of the peri-urban agriculture industry in professional production and scaled-up management, contributing to the increase in local production and supply of fresh food. Interestingly, China’s first agritainment was originated in Chengdu in 1987, for the first time demonstrating extra functions of agriculture in addition to food production in China, which builds sound foundation for future development of urban agriculture.

The second phase (1999–2008) started from 1999 when future strategies of agriculture in Chengdu were discussed over the Peri-Urban Agriculture Strategy Consultation Workshop. The concept of urban modern agriculture was raised in the workshop, signifying its emergence in Chengdu. In 2001, urban agriculture was recognized as an effective measure to increase income of peri-urban farmers during the 11th Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) of Chengdu. In 2003, the Master Plan of Chengdu proposed to support the development of urban modern agriculture through a series of actions [

32]. In 2004, the Chengdu Municipal Party Committee announced to modify the structure of agriculture and support a variety of urban agriculture typologies such as facility agriculture and ecological agriculture. Chengdu was also selected as urban agriculture pilot city by RUAF in 2006 and pilot area of coordinated urban-rural reform by the national government in 2007, bringing great opportunities to develop urban agriculture in Chengdu.

During the third phase (2009–2016), urban agriculture was rapidly developed and widely practiced in Chengdu. New typologies such as leisure agriculture, sightseeing agriculture and creative agriculture emerged in large amount. In 2009, the Chengdu Modern Agriculture Planning (2008–2017) announced the overall strategies of urban modern agriculture by spatially designating three concentric circles with distinct focus of development [

33]. In 2012, the 12th Party Congress in Chengdu defined the key elements of urban modern agriculture for Chengdu, including modern technologies, advanced management, modern farmers, and industry convergence. In 2016, Chengdu further defined the objective of urban modern agriculture as to become a model city of urban agriculture in China [

34].

From 2017 to the present, urban agriculture of Chengdu enters the period of high-quality development. In 2017, the National Central City Industrial Development Conference identified six major industries that could be derived from the urban modern agriculture in Chengdu, namely deep processing of agricultural products, urban leisure agriculture, rural e-commerce, health and wellness, logistics of agricultural products, and green cultivation [

35], marked the high-quality and value-added outcomes out of the urban agriculture industry. In this phase, Chengdu’s strategies of urban agriculture have been keeping improved and adapted to City’s High-Quality Development Strategy and the national Rural Revitalization Strategy for effective transformation and upgrading of the agriculture industry.

3.3. Resources and Capacity

Chengdu locates on the Sichuan Basin. The west of the city is on the west edge of the basin with the altitude of 1000–3000 m. The east of the city lies at the bottom of the basin on Chengdu Plain, known as “The Land of Abundance” because of the abundant resources in the plain area. The land typologies of Chengdu are divided into three parts, the mountain area (32.3%) suitable for growing medicinal plants, the plain area (40.1%) suitable for vegetables and cereals, and the hilly area (27.6%) suitable for orchards and mushrooms. The soil is fertile, with average land reclamation index reaching 38.22%, far higher than the national average rate of 10.4% [

30]. Water resources of Chengdu are sufficient, although the usage amount per capita is not as much. The total annual water amount is 30.472 billion cubic meters (cbm), including 3.158 billion cbm of underground water, 18.417 billion cbm of surface water and abundant rainfall [

36]. There are more than ten main river streams, dozens of river branches, and scattered reservoirs, ponds and canals within the city. Notably, the unprecedented Dujiangyan Water Conservancy Project built in 256BC on the west of the Chengdu Plain has been considerably benefiting the agricultural irrigation and water use of Sichuan Province. The climate of Chengdu is the humid subtropical monsoon climate, with average temperature at 16 °C and annual rainfall at 1000 mm. Therefore, with fertile soil, gentle climate and convenient irrigation conditions, the natural resources available in Chengdu suggest high capacity in urban agriculture that could meet urban dwellers’ demand in healthy food and sustainable life.

In terms of socioeconomic conditions, mechanisms to access human resources and financial resources for urban agriculture were taken into consideration. The city has developed a farmer training and evaluation system in 2012. More than 100,500 professional farmers have been trained as of the end of 2019, 17,100 of which were professional managers [

37]. This system provides a useful official mechanism of capacity development for local practitioners in agricultural activities and management. Chengdu also established a City Agriculture Think-Tank comprised of leading multi-stakeholders including hundreds of agricultural enterprises and research institutions, to attract, train and support talents in agriculture innovation and entrepreneurship. These practices have ensured the high quality of human resources in urban agriculture.

As China’s first pilot city in the rural financial service reform, Chengdu set up the “NongDaiTong” Financing Service Platform that provides a series of services in agricultural financing, insurance, credit, property right, e-commerce and agricultural policy, establishing effective connections among governments, financing institutions and agricultural entities or farmers (

www.ndtcd.cn). The system has also set sub-level service platform for each district/county, street/town, and community/village, ensuring a wide access of these economic services for the practitioners and subsequently guaranteeing their capacity and resilience in finance. There have also been innovative explorations in land transfer systems. In 2008, Chengdu founded China’s first Rural Property Right Exchange where farmers can officially transfer land contract operation right, rural housing ownership, and the collective construction land use rights. Additionally, Chengdu committed to designate no less than 8% of annual land use in developing new industries and businesses in agriculture and food [

38].

The assessment has revealed that Chengdu embedded good basis in both natural and socio-economic resources for a long-term development of urban modern agriculture that could facilitate urban-rural linkage and city sustainability, building on which strategic planning of the industry is highly necessary to wisely allocate resources, make full use of the synergies and maximize the city’s capacities in food supply, ecology preservation, economic development and social wellbeing.

4. Practices and Performance

4.1. Ensuring Supply and Booming Industries: Urban Modern Agriculture Functional Zone

Functional Zone is an innovative practice in Chengdu for better coordination and resource aggregation among different sectors in a systemic manner. The 2016–2025 Urban Modern Agriculture Functional Zone Planning was approved by the municipal government in 2016 [

39]. After a few adjustments along the implementation, now seven Urban Agriculture Functional Zones are designated (

Figure 3), each with distinct spatial advantages, development strategies, major agricultural products or services and typical practices (

Table 3). Innovative governance approaches, such as the “management committee + operation company” model, are being explored. In two of the zones, a trilateral management mechanism has been piloted, attempting to well integrate the zone management with local administration and achieve synergies between the urban agriculture industry development and public administration and social services [

31].

The Alliance for Urban Modern Agriculture Functional Zone (AUAFZ, Chengdu, China) was established with support from the Agriculture and Rural Affairs Bureau and the Institute of Urban Agriculture (IUA, Chengdu, China), Chinese Academy for Agricultural Sciences. The Alliance organizes regular meetings for the practitioners and grassroots management of the zones to exchange good practices and discuss on challenges. The Alliance also supports the zones to seek technical support and other local resources. An annual evaluation of the zones is scheduled for regular monitoring and reviewing of the practices and outputs, which is of great help to adjust goals and actions and troubleshooting issues in production and management activities.

The setting of the functional zones provides an enabling environment for urban agriculture practitioners to access to resources, collaborate with upstream and downstream entities in a participatory approach, forming effective synergies along the food value chains. Increase in the average income of residents in the zones was observed as compared to that of the district or county in which the zones are located [

31], suggesting the benefits this innovative practice has brought to the regional socioeconomic development.

4.2. Multifunctionality and Sustainability: The Urban Agriculture Cross Strategy

From a city development perspective, Chengdu released the “cross strategy” during the Central City Industry Development Conference in 2017, which became an additional driving force in terms of the urban agriculture development, specifically, the presentation of the multifunctionality of urban agriculture and its contributions to the sustainability.

Briefly, the strategy divided the city area into five regions, the eastern region (3976 km

2), the western region (7185 km

2), the southern region (1395 km

2), the northern region (704 km

2), and the central region (1264 km

2), with various developing priorities identified for each [

40]. Along with the differentiated development path, the five regions have developed distinct practices demonstrating diverse functions of urban agriculture, indicating the different dimensions from which urban agriculture can contribute to the city sustainability development.

Taking a close look, the eastern region has very good ecological basis, thus, it has displayed the environmental function of agriculture in peri-urban areas, with greenbelts built across the region. Twenty-two typical towns have been invested for the agri-tourism industry with components of leisure agriculture and organic agriculture. The western region is a major cereal production contributor due to the high capacity of the land in cereal growth. The western region also plays an important role in agricultural culture preservation and the development of environmental-friendly production technologies, due to the existence of a large number of the Linpan traditional agricultural systems in this region. The focus of the northern region is the economic aspect of urban agriculture. Efforts have been paid in increasing the business capacities of the urban agriculture practitioners by improving logistics and service systems in agricultural production and management. Innovative practices that added economic value of urban agriculture products are demonstrated in the Chengdu Modern Agriculture Open Economy Demonstration Area located in the northern region. In the southern region, the social function of urban agriculture is widely practiced and explored. There are around 40 star-ranked agri-tourism entities and 72 urban agriculture gardens with sightseeing, education and customer experience services. The region aims to become China’s model area in leisure agriculture, exploring suitable models to integrate the multiple functions of urban agriculture. As for the central region responsible for the city’s core function, urban agriculture and green spaces in this region mainly focus on the development of innovative and pleasant micro-environments featuring food elements that contribute to the Park City vision of Chengdu, in order to improve the quality of urban dwellers’ lives. Example practices include the establishment of school gardens, home micro-gardens and scenery agricultural spaces in populated places. It is still an early stage for Chengdu to develop agriculture in the populated urban center, thus requiring support from governments and participatory contributions from all sides of the society.

The Urban Agriculture Cross Strategy allows different regions to make use of the local advantages and explore new forms of agriculture based on the multi-functional nature of urban agriculture. By means of integrating the social and cultural aspects in peri-urban and rural agriculture while embedding the food production elements in urban settings, supposedly strategy would be able to facilitate the multifunctionality of urban agriculture and sustainability of the city development.

5. Opportunities and Challenges

Upon reviewing the overall environment of urban agriculture in Chengdu, both opportunities and challenges have been observed for a sustainable development pathway of Chengdu’s urban agriculture.

Opportunities of urban agriculture in Chengdu are reflected in the increasing demand of various dimensions and increasing visibility in the city development strategies. Overall, the urbanization results in rapid increase in urban population but shrinking in agricultural land and number of traditional producers, making to guarantee the urban food and nutrition security a latent challenge. The frequent natural shocks caused by climate change and public health disasters like the unprecedented COVID19 pandemic have exaggerated the risk in food supply under emergencies. Data showed the self-sufficiency rate of staple food in Chengdu was 83.82% in 2019, to some extent suggesting potential threats in food security. Urban and peri-urban agriculture, as a form of food production that is close to city settings and explores innovative high-tech production systems in some areas, shortens the food supply chain and contributes to local food self-sufficiency and food system resilience in case of emergencies [

41]. From a city governance perspective, the phenomenon of urban-rural polarization has been observed in China after a period of rapid economic development in the past decades. Urban agriculture, especially the peri-urban agriculture that physically and economically connects the urban and rural spheres, is always leading the innovative practices in transforming the traditional agriculture forms and diversifying farm activities and services by means of multifunctionality development in the countryside, which can facilitate the flow and aggregation of factors of production such as capital, land, talent, and technologies between urban and the countryside, and in turn upgrade the agri-food value chains, increase farmers’ income and improve the social equity [

11,

42]. Additionally, demands of consumers are also changing. On the one hand, now more attention has been paid on the safety and freshness of the daily consumed food. In a survey we conducted on consumers’ perception on the function of urban agriculture, the highest proportion of respondents agreed that provision of fresh and health food is a key outcome of conducing urban agriculture (unpublished). On the other hand, natural places with ecological scenery and food-related experiences have become the hotspot of entertainment choices. The total income of countryside tourism in Chengdu was 48.92 billion yuan in 2019, increased by 24.2% than that of 2018 [

43], suggesting great opportunities for the leisure form of urban agriculture in Chengdu.

Further, the support in urban agriculture observed in different levels of agriculture and food strategies have provided an enabling environment for urban agriculture development in Chengdu. Internationally, The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN) started to support urban agriculture since the 1990s, when the UN Conference (Habitat II) pointed out the compatibility of urban agriculture with the increasing urbanization [

44]. Numerous programs and initiatives have been undertaken since then to support urban agriculture activities and policies in different countries and areas [

45]. The FAO advocates that urban agriculture is a complement source of food supply for cities and it is crucial to strengthen the complex linkages between urban, peri-urban, and rural agriculture to enhance the food security and resilience of city regions. In 2020, the newly launched Green Cities Initiative further recognized the key role of urban agriculture in city development and urban dwellers’ life quality and well-beings [

46]. At a national level, China started to implement the Rural Revitalization Strategy in 2018 [

47], serving as a key approach to deal with issues relating to agriculture, farmer and rural areas and to achieve the modernization of agriculture and rural areas. Among the actions and expected outputs raised by the strategy, high relevance to urban agriculture’s contributions is observed, such as the items of strengthening the urban-rural integration, preserving environmental values, promoting agriculture culture, innovating governance mechanisms and conducting targeted poverty alleviation. This has suggested the leading role that urban agriculture could play in the agriculture and food sector in China. Locally, the municipal government of Chengdu also introduced a series of supporting policies regarding urban agriculture. In 2007, Chengdu became the pilot city of the national reform for urban-rural integration development [

48]. In 2009, two guiding policies were formulated on accelerating the integration of urban-rural areas and to facilitate construction of urban agriculture bases. In 2015, the national government designated Chengdu to be the pilot city of rural reforms, allowing Chengdu to further the attempts in urban-rural integrated development and to play a leading role in China. In 2018, Chengdu introduced the concept of “Park City” for the first time in China. Urban modern agriculture appeared to be an important component in the Park City Action Plans, responsible for the city’s high-quality food supply, urban-rural linkages and sustainable development [

49]. More recently, strategic regional coordinated development plans, such as the “Chengdu-Chongqing City Cluster” strategies and the “Chengdu-Deyang-Meishan-Ziyang Metropolitan” strategies, further offer historical incentives for urban modern agriculture to lead the role in high-quality food supply, food system transformation and improved urban-rural relationship in a new era of development.

Despite of the great opportunities and potentials, urban agriculture still faces various challenges in Chengdu and in China. These include but are not limited to: (1) Lack of solid research in this new area, from new technologies that are affordable and suitable for the city settings, to approaches to systemically link urban agriculture with city development and governance; (2) issues in farmland preservation, especially the peri-urban land that tends to be occupied by the urban expansion while also subject to metal pollution and damages in cultivation layer and irrigation systems; (3) lack of holistic assessing and monitoring systems and database for evidence-based systemic planning; and (4) limit in terms of institutional systems, requiring further exploration and innovation.

6. In-Depth Assessment Framework

As an attempt in establishing the holistic assessment system and monitoring database for urban agriculture in Chengdu, a systemic indicator framework has been developed upon determining five main aspects of urban agriculture for Chengdu (

Table 4). These include: (1) Food supply; (2) value export; (3) leisure agriculture; (4) resource agglomeration; and (5) food governance. The food supply theme took a food system approach to identify the indicators along the core supply chain while taking consideration of social and environmental impacts along the chain. The value export theme concerns the export and influence of local agricultural products that are embedded with local culture, reflected by three sub-themes, namely the value chain quality, branding activities and the reputation and impacts of these products or industries. Leisure agriculture is an important form of urban agriculture with great potential benefits for both urban and rural dwellers, especially in Chengdu where there is good culture for agritourism. Within the theme of leisure agriculture, the capacity, performance, and impacts were selected to be sub-themes to assess and monitor, assumed as key elements for successful leisure agriculture. Resource agglomeration is agreed to be a major function of urban agriculture in Chengdu, thus the flow and innovation in integrating different resources required for urban agriculture is assessed under this framework. Finally, food governance needs to be assessed to ensure an enabling environment for all relevant activities, in which the current status of policies and the supporting mechanisms are determined as sub-themes for the assessment. The weight of each indicator was determined using the AHP method and provided in

Table 4 for use in data analysis. This framework can also be applied in other Chinese cities upon adaption.

To verify the framework, a pilot in-depth assessment using the above indicator framework was conducted for the seven Urban Agriculture Functional Zones in Chengdu. Under the assumption that the performance of the seven zones could largely reflect Chengdu’s status of urban agriculture, the average score of the seven zones was calculated, following which the score for the sub-themes and themes was obtained according to the defined indicator weight (

Figure 4).

Figure 4F illustrates the overall performance of the five main themes, indicating slight weakness in resource agglomeration. Taking a closer look into the sub-themes,

Figure 4E suggests that the main drawback within the resource agglomeration aspect was the flow of factors, while the other sub-themes also performed worse than those of other themes. This may be due to the polarized urban-rural relations in China in the past, bringing more difficulties today in the flow of factors and in synergies of resources and expertise between urban and rural areas.

Figure 4A,C,E revealed relatively weak performance in diet and nutrition of the “food supply” theme, output and impact of the “leisure agriculture” theme, and supporting mechanism of the “food governance” theme, respectively. Results of the diet and nutrition are in consistency with what was found by the Scientific Research Report of Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents (2021) [

50], which demonstrated dramatic increase of overweight, obesity, and diet-related chronic diseases in China. Imbalanced diets were found to be the main driving factor for diseases and deaths in China, suggesting an urgent need to improve residents’ diets and nutrition. In terms of the output and impact results of leisure agriculture, economic impacts calculated by “total income growth of leisure agriculture and agro-tourism” obtained a low score at 0.69, which may be largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic impacts in residents’ tourism activities. While the social impacts calculated by the “employment growth in sized enterprises” were scored at 0.77, lower than most indicators, suggesting a limit in measuring measures of the indicator due to data availability. Social impacts of leisure agriculture could be achieved in various dimensions such as the benefits in strengthening urban dwellers’ communications and positive cognition on the agri-food sector, which need to be measured through field surveys in the future assessment. In addition, the score difference between supporting mechanism and policy status in the food governance aspect suggested a developing process of the city’s policy environment to support urban agriculture. Increasing policies supporting the urban agriculture development were observed, yet the supporting systems to enable concrete implementation of these policies such as evaluation and monitoring systems and talent systems still need to be established and improved in the coming years.

7. Conclusions

Based on the assessment of urban agriculture in Chengdu conducted in this study, it was concluded that Chengdu has good historical foundation and access to resources for urban agriculture. Practices observed in the city also revealed systemic thinking in terms of strategy making and innovation abilities in not only ensuring food supply but also achieving multiple dimensions of impacts in the city sustainability development. Together with an analysis of diverse demands and relevant policy agenda, huge opportunities for urban agriculture have been identified in Chengdu, while a range of challenges were also observed such as lack of complete research system in this new discipline and the complex land use dilemma, which could be long-term issues to be dealt with.

Given that a comprehensive framework for in-depth assessment and monitoring is also lacking, this study then developed a systemic indicator framework with the final goal of establishing a complete assessment toolbox and monitoring database for urban agriculture adapted for Chinese cities. A pilot in-depth assessment using the framework was then conducted using data of the Urban Agriculture Functional Zones in Chengdu. Results of the assessment revealed weakness in resource agglomeration, particularly in the flow of factors. Resource agglomeration is indeed important for making use of synergies among various sectors and regions, considered a key component of urban agriculture and urban-rural integrated development. Therefore, it is recommended that policy-makers and researchers look into the root causes of the issues and research on driving factors, which will be of help for better food planning. Another notable weak point is the diet and nutrition of the consumers, again stressing the necessity of transforming the current food systems by building sustainable and nutrition-driven food supply chains, in which urban agriculture should play a leading role. As an exercise to verify the framework, the pilot assessment also reflected some data gaps that require further investigation through field surveys. These included several items in “the level of consumption” and “diet and nutrition” in the food supply theme, which also suggested a lack of attention in the food environment research, particularly in consumer behaviors and nutritional impacts of the local food systems.

In summary, the outcomes from the assessments in the present study have not only provided concrete information of urban agriculture in Chengdu, but also suggested the feasibility and effectiveness of the systemic indicator framework developed in this study, providing a good basic model to be further improved and adapted in more empirical studies in Chinese cities. It is expected that a transferable urban agriculture assessment toolbox is developed based on the present study with the final goal of supporting city food planning in China.