Abstract

Educational sustainability development (ESD) is central to our sustainable future. To promote inclusive and equitable quality education under the backdrop of sustainable developmental goals (SDGs), we intend to understand how rural students perform in academic studies of post-compulsory high-school education in China by assessing their academic performance based on measurements of four content subjects: Chinese, English, Physics and Biology. A total of 93 senior high school students (Grade 11 and Grade 12) participated in this study and they were enrolled in a rural school from the Guizhou province, China. Our results yielded no significant differences in overall test scores between Grade 11 and Grade 12. Repeated measures multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) across grade level showed stagnant progress in English reading and a decrease in science-related subjects, which indicates a plateau of academic achievements in rural secondary education. Furthermore, the interactional analysis identified a gender gap leaning toward male students because boys scored higher than girls in the three tested subjects. Applied implications were discussed with respect to sustainable education development in rural areas.

1. Introduction

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is perceived as a crucial enabler for sustainable development [1], and serves as a lever in the international education sector. Global communities have affirmed the commitment to equity and quality in education under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) banner. Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) signals a far-reaching commitment to ensure ‘inclusive and equitable quality education for all and promote lifelong learning at all levels of education [2]. Notably, the SDG 4 represents a shift of focus from universal education toward quality education. Another key feature in SDG 4 is the emphasis on equity in education. The concept of equity draws upon a boarder scope, which ensures equal resourcing of education for boys and girls across rural-urban backgrounds and socioeconomic status. In spite of the wide implementation and achievements in ESD, marginalized communities such as rural and remote regions are still plagued by limited educational resources, together with over-crowded and underequipped learning conditions and unqualified teachers [3]. The effectiveness of inclusive and equitable quality education in rural communities is a valuable but underexplored issue. In the landscape of Chinese rural education, education for all has been largely guaranteed because of the implementation of the nine-year compulsory education system. There is a shift of focus on quality education in post-compulsory education or upper secondary education, which is gathering momentum as outlined by China’s 13th Five-year Plan [4]. High school is crucial as it lays the foundation for future growth from youth to well-prepared and resilient adulthood. Nonetheless, research suggests that academic test scores can plummet during the students’ transition to senior high schools [5]. What awaits to be further investigated is academic performance in the rural setting, as a majority of studies emphasize urban students from developed areas [6]. Little has been investigated with regard to how rural high school students perform in academic studies. Given the large rural population in China, the success of sustaining economic growth hinges more on development in rural areas and education is a soft power to facilitate sustainable development. Therefore, it is worth researching in the rural context and more specifically, assessing rural students’ academic achievements to identify the learning problems for future improvements. Furthermore, in order to be admitted to good colleges, Chinese students need to excel in the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE) and limited resources in underdeveloped areas may hinder students’ chances of getting into colleges. The general diversification of curricula asks high school students to choose core content areas such as foci (liberal arts or natural sciences). The required selection of content subjects divides students into two tracks, which might lead to a gender disparity in academic performance in both content areas [7]. To that end, research is needed to diagnose academic performance and educational outcomes among rural students of different genders. Drawing upon four subject-specific measurements, the current study aimed to assess students’ academic performances through comparing grade level and gender to examine the progress or stagnation in students’ performance across grade level, as well as the gender discrepancy in academic performances. In doing so, we would be able to shed light on the reform of sustainable high-school education in the Chinese rural context.

1.1. Rural Education in China

Given that over one third of the Chinese population is living in rural regions, rural education is inextricably linked with sustaining growth. There has been increased attention to rural education, with a fueled national ambition to put the focus of rural education on the agenda. Since 1986, the starting point of China’s implementation of the free compulsory education policy, access to basic education has been guaranteed for students from rural impoverished families who cannot afford the tuition. The policy covers six years of elementary school and three years of middle school [8], relieving the economic burden for the rural population. China is now working further to address the educational gaps in rural areas. There are two common values of the Chinese current education policies: justice and quality. In the past decade, as a response to education for sustainable development, China designated several strategic goals as outlined in China’s National Plan for Medium and Long-term Education Reform and Development 2010–2020: (a) promoting early education, including universal preschool education in transition to nine-year compulsory education; (b) fostering equitable education; (c) enhancing the quality of education; (d) building an exemplary framework for lifelong education [9]. Under the strategic plans, there has been a significant increase in attainment for elementary and middle school education in underdeveloped areas. Guided by education policies, the implementation of compulsory education has permeated throughout China within ten years [10]. However, the focus on progress in compulsory education obscures a larger picture concerning education equity in China. Inequalities in access to quality education and in academic achievements remain obstinately persistent in rural areas. According to China’s educational statistics in 2010–2012, the average enrollment rate of high school students was only 6% in rural areas compared with 63% in urban areas. Only 3 of 100 rural children could finally graduate from high school [11]. In 2015, 60% of students that failed to complete high school education were from impoverished areas or low socioeconomic backgrounds [12].

Research on Chinese rural education suggests that poverty is associated with academic performance, and that students from underdeveloped rural areas are susceptible to drop out and are more inclined to obtain low levels of educational attainment [13,14,15]. Prior studies on Chinese educational attainments found that individuals with the urban registration system (hukou) exhibited higher years of schooling than those with rural hukou [16]. Adopting Gini education coefficients and decomposition analysis, the study of Qian and Smyth found that educational inequality in China stemmed mainly from the disparity between rural and urban areas [17]. It should also be noted that there is a pronounced rural-urban gap in Western China, where education development lags far behind [18]. In 2010, the Gini coefficients on education (index for education inequality) for the Guizhou province in southwest China were 0.36 in rural areas and 0.30 in urban areas, indicating the existence of significant educational gaps [18].

Indeed, studies have confirmed that educational outcomes in rural areas are constrained by family background, household poverty, and culturally marginalized geographic location, etc. [19,20]. The educational disadvantage in rural areas partly comes from geographic factors, providing fewer opportunities to school education [21]. Geographic isolation in rural areas renders educational resources inaccessible, and poses another challenge to attract highly qualified teachers [22]. Apart from deficient educational resources, schools in rural China are characterized by insufficient financial support [23], overcrowded classrooms [24], and unqualified teachers [25]. These realities have worsened the advances of quality education, especially in the post-compulsory high school context and may restrain students’ academic achievements.

Accessibility in universal education is becoming less of a barrier in China, but as has been noted, inclusive and equitable quality education in rural areas is only half the battle with unresolved challenges. Education is considered the blade that can alleviate poverty by imparting knowledge and cultivating the young generation. Post-compulsory education and quality education for rural students have become central issues in the educational landscape. Therefore, it should be worth investigating the academic achievement of rural students to pinpoint their learning problems at post-compulsory education level.

1.2. Academic Achievements in Chinese High-School Education

There are two types of schools at the Chinese high-school level: general high schools (gaozhong) and vocational schools (zhongzhi). The former follows an academic track while the latter imparts technical training. Students from general high schools face more severe competition as they are required to take the national college entrance examination (gaokao). General academic schooling is best considered as a ‘3 + X’ system that covers three compulsory subjects and several optional subjects. In addition to three compulsory subjects (Chinese, mathematics and English), students need to choose from a variety of science subjects (physics, biology and chemistry) or liberal arts subjects (history, geography and political science). Regional variations can be seen in some provinces, whereby ‘X’ can represent a combination of subjects selected from a list of six [26]. Based on the content in the college entrance examination, students are divided into two tracks in the second year: the humanity track and the science track. The humanity and science division in the 3 + X system aims to enhance the quality of high school education and to reduce the academic burden on the students. However, high school students are struggling to improve their academic scores since this post-compulsory system is examination-oriented. Moreover, the possibility of attending college is contingent upon the total scores of these subjects in the college entrance examination. Therefore, it is a highly selective and life-determining method for entry into universities [27].

Academic achievement refers to the extent to which students have achieved their educational outcomes. General academic performance can be measured through average grade points of an ability test. When considering academic achievement in the school context, the issue of gender gaps cannot be overlooked. A multitude of previous studies have explored the impact of gender variations in academic achievements [7,28]. On the one hand, studies investigating gender variations in academic performances have indicated a slight female advantage in reading and liberal arts-related subjects [29]. Compared with their male peers, girls not only have higher intrinsic motivation towards reading at all levels of education [30,31], but also attain better achievements in high school as indicated in the study of Sun et al. [32]. They sampled all senior high school students in a third-tier Chinese city from grade 10 to grade 12. By investigating students’ academic test scores in a city-wide high school examination, the study underlined that girls outperformed their counterparts in all liberal arts subjects like Chinese and English. In contrast, there was a gender gap in favor of boys in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)-related subjects in senior secondary school years. As pointed out by Makarova [33], STEM-school subjects were perceived as male dominant by secondary school students. They argued that females were often underrepresented in science-related educational performance and confirmed a gender stereotype bearing masculine image in subjects like mathematics and physics. In line with this argument, Hand [34] reported lower self-efficacy for girls in high school mathematics and science subjects. The research of Riegle et al. [35] further pinpointed that variations in science course-taking gaps in high school may be attributed to the local community labor force. By investigating gender gaps among 80 high schools, they found that the male advantage in physics significantly reduced or disappeared in schools situated within communities that had more women employed in STEM professions. The extant literature is replete with investigations on educational outcomes between boys and girls. How gender gaps, if any, affect high school academic performance in rural communities is yet an unanswered question.

Another relevant issue regarding high school academic achievement is to consider the spectrum of quality rural education. As noted above, the educational inequality in access to high school education is most salient in Chinese rural areas. Pertaining to educational quality, high underachievement rates permeate in Chinese rural high schools, and are now exacerbating with grade level [36]. For instance, the study of Zhang [37] on Chinese high school students revealed that rural students showed little interest in English learning and exhibited low levels of motivation. It is worth mentioning that ethnic minority rural areas, which are impoverished and geographically remote in nature, had the biggest challenge [38]. Fee-based systems create barriers for rural students who cannot afford the school tuitions due to economic hardships. In addition, isolated village schools are often not staffed by highly qualified teachers. The diversification of examination that contains a variety of domain-specific selective subjects such as English language and science subjects tends to impede education of rural students [39]. In this respect, rural students are most likely to be identified as underachievers in high school assessments. There is a dearth of studies investigating students’ academic achievement in rural minority areas. The question of how the rural youth achieve in academic performance in the high school context remains to be explored.

Though rural education has been accorded much importance in China during the past decades, the commitment to an inclusive and equitable quality education is yet to be fulfilled in rural regions. Given the little empirical evidence in this field, the current cross-sectional study used four measurements as performance indicators to examine the academic achievement of rural high school students in Western China, so as to shed light on equity and quality of upper secondary education under the global banner of education for sustainable development. More specifically, the current study aims to explore (1) whether academic performances differ across grade level in Chinese rural students; and (2) whether learner attributes (gender and grade level) differentiate academic achievements among Chinese rural students.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participating School

The participating high school is from one of the most underdeveloped rural areas in southwest China, a National Poverty County (Yanhe Autonomous County) located in a geographically remote region of Guizhou province. Based on statistics from the National Bureau of China, Guizhou ranked the fifth to last with a per capita GDP of 16,769 RMB in 2019. Constrained by historical and geographic factors, Yanhe Tujia Autonomous County was still in deep poverty during the data collection, as indicated by the high poverty incidence rate of 7.4% in 2018. In 2019, Yanhe Tujia Autonomous County has a total population of 690,800, consisting of people from various ethnic minorities such as Tujia and Miao [40].

2.2. Participants

A total of 93 students (56 males and 37 females, mean age = 16.6 years) were enrolled from a local high school. Among the participants, 42 students were sophomore (n = 42; 45%) and 51 were junior (n = 51; 55%). The majority of the participants was from the Tujia ethnic group (98%), while the rest participants were identified as the Han ethnicity. They were mostly from lower-middle- and working-class families.

2.3. Measures

Four academic measurements were adopted to compare academic achievements between students from two grade levels (11th grade and 12th grade), including Chinese reading test, English reading test, and discipline-related knowledge test in the domains of physics and biology.

2.3.1. Physics and Biology Academic Knowledge Test

This test was adopted from the comprehensive science test of College Entrance Examination. Physics and biology questions were measured in the test and the questions were problem-solving ones. Each question was followed by four multiple choices. The students needed to choose the best answer based on each presented description. There was a total of 40 questions in this task.

2.3.2. Chinese Reading Ability Test

Chinese reading ability test was also adopted from the Chinese test of College Entrance Examination. The test consisted of two multiple choice items and three short answer questions that could reduce the guessing rate according to the provided options. These items were designed to measure test takers’ literal and inferential comprehension of the target passage.

2.3.3. English Reading Test

English reading test was used to measure learners’ English reading comprehension ability. The task included four passages with a comparable length from 352 to 389 words. The passages were all selected from the model tests of CET (College English Test). Each text was followed by multiple choice questions. Each question had five choices, and students were asked to select the most appropriate one. The total number of items was 20.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

The study was approved by the ethics committee of researchers’ institution and the written informed consent was obtained prior to the tests. Data were collected in the students’ regular classes in the middle of fall semester. All measurements were administered to participants in a small group session. The total allotment for the entire test was two hours.

2.5. Data Analysis

We began the analysis with descriptive analyses. Mean and standard deviation were computed for tested variables in two groups (Table 1). Then, data were treated by removing outliers. Shapiro–Wilk tests of normality showed that normal distribution for Chinese and English reading measures was well met in both groups, ps > 0.05, whereas the data of physics and biology academic knowledge test scores were not normally distributed, ps < 0.001. We used rank-case transformation to normalize the data, which was considered to be a better strategy than logarithm and Box-Cox transformations with a small sample size [41]. Normal scores transformed based on Blom’s formula were used in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of tested variables in senior 2- and 3-year students.

After checking that the assumptions were met, we conducted between-group analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the total test scores between two groups. Then, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed to determine whether there was a significant difference in multiple academic achievement scores (i.e., Chinese reading, English reading, physics academic knowledge, biology academic knowledge) between 11th and 12th graders. The MANCOVA test was performed with grade as an independent variable, with gender as a covariant and with four measures of academic achievement as dependent variables. To probe into the interaction effects of gender and grade, we used simple effects analyses. This approach allowed us to investigate the collective and individual effects of grade and gender on multiple academic test scores.

3. Results

3.1. RQ1. Do Academic Performances Differ across Grade Level in Chinese Rural Students?

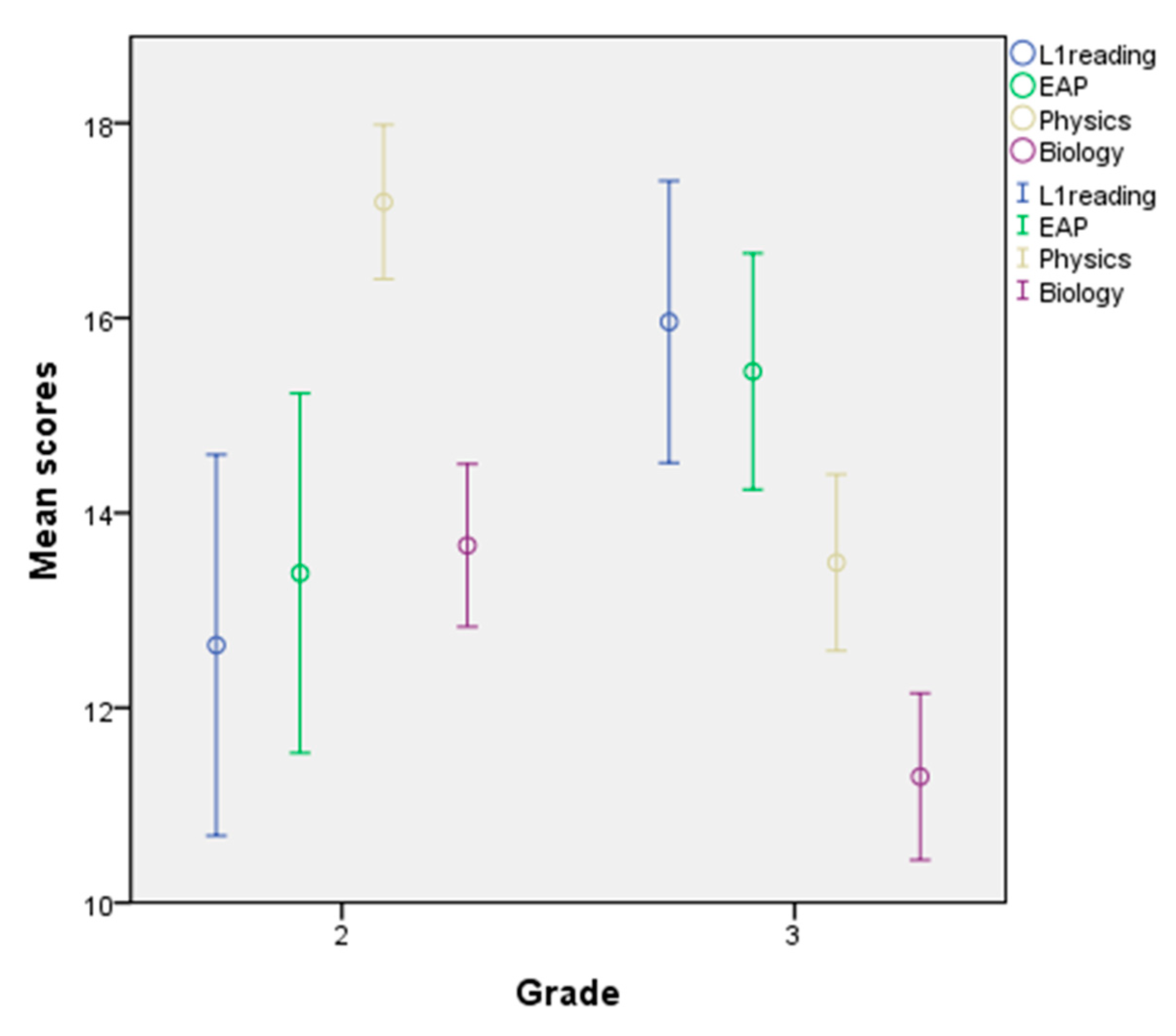

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of scores on four academic measures from two grade levels. For each student group, the maximum score on Chinese reading tasks was 30, and the maximum score of English, physics and biology academic knowledge tasks was 20. The results of Tukey’s exploratory data analysis displayed similar mean scores. The 11th and 12th graders had average scores of 56.88 and 56.20, with 50% of the students in each group scoring between 50 and 65, indicating that total academic performance in Grade 11 was similar to that attained in Grade 12. It can also be found that there was large dispersion in individual students’ scores with more than three SDs indicating the notable difference between low achievers and high performers. In addition, 11th and 12th grade students exhibited uneven and different patterns of test scores given that average physics and biology scores dropped but average English and Chinese scores increased. Figure 1 also presents the graphic comparisons between the participant groups.

Table 2.

Effects of grade and gender on multiple academic knowledge measures examined by MANCOVA analyses.

Figure 1.

Error bar chart of academic test scores across grade level.

3.2. RQ2. Do Learner Attributes (Gender and Grade Level) Differentiate Academic Achievements among Chinese Rural Students?

The one-way between-group ANOVA was conducted to determine whether students from two grade levels differ in overall academic performance. On the total scores, the ANOVA did not reveal any significant group differences, F (1, 92) = 0.09, p = 0.764, and the effect size was small η2 = 0.001. Assumptions of ANOVA were met as the Levene’s test showed equal homogeneity of variance across grade, p = 0.885. The results demonstrated that overall academic progress tended to stagnate, as 11th graders performed equally well by comparison with 12th graders. MANCOVA was then conducted on four scores of academic achievement. First of all, the results yielded a significant effect of grade on academic performance, Wilks’ lambda, λ = 0.563, F (1, 89) = 19.60, p = 0.000, η2 = 0.474. Box’s M test of equity of covariance matrices showed homogeneity of variance across groups, p = 0.391; thus, the assumption of MANCOVA was met. There were significant effects of grade on three academic measurements (Chinese reading: F (1, 89) = 7.76, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.08, Levene test p = 0.063; Physics: F (1, 89) = 36.11, p < 0.000, η2 = 0.29, Levene test p = 0.436; Biology: F (1, 89) = 15.31, p < 0.000, η2 = 0.14, Levene test p = 0.558). The covariate of gender was not significant. Although 12th graders outperformed 11th graders on the Chinese reading task, they scored significantly lower than their counterparts in both physics and biology academic knowledge tests. While English academic scores remained relatively stable, there was significant progress in Chinese achievement. In addition, concerning English reading, no significant effect of grade was found. These results indicated that overall academic achievement remained stagnant, and that a few discipline areas even had a backward change in this underdeveloped area.

With regard to the gender effect, we used simple effects analyses for all academic scores to scrutinize the interaction effects of grade and gender. There was no significant interaction effect of gender and grade in the English reading scores. Although performance in physics and biology both declined in Grade 12 for all students regardless of their gender, there were more significant score drops in girls, ps < 0.001. In addition, the simple effect analyses revealed that biology scores remained stable for boys but declined by 1 point among girls, and plummeted at the significance level in Grade 12, p < 0.001. Finally, concerning Chinese reading, the results identified a substantial increase in scores for boys across two grades, p = 0.019, but this grade effect was not significant for girls, p = 0.147. In other words, the results indicated that boys had the stronger potential to improve. In all, the results showed that girls lagged behind their male counterparts in most of academic contents which indicates a potential gender gap in academic achievements in the Chinese rural educational landscape.

4. Discussion

Education for sustainable development underpins inclusive and equitable quality education in the global context. The present study aimed to examine sustainable rural education through the lens of academic assessments in a Chinese impoverished area. The study investigated four discipline areas: Chinese, English, Biology and Physics. Gains in test scores across grade levels could serve as a manifestation of effective quality education in southwest China. Specifically, we focused on two objectives: (1) whether academic performances differ across grade level in Chinese rural students; and (2) whether academic achievements vary according to learner attributes (gender and grade level) among Chinese rural students.

First, the findings revealed that there was no salient group effect on overall achievement measures between students from Grade 11 and Grade 12, which suggests a slight improvement in senior high school performance. Although the extant literature generally agrees on a statistically significant difference in students’ academic performance across grade level in secondary school [42], our study did not generate the significant pattern between grade level and overall academic test scores in this particular group of students. It is important to ponder the reason why 11th graders attained similar test scores to 12th graders. One possible explanation is to consider the unique characteristics and dilemma of rural education at the school level. As mentioned above, the participating school is in a local impoverished county which encounters the same challenges as other remote regions: insufficient infrastructure and facility, shortage of qualified teachers and educational resources. Teaching quality varied in different geographic regions due to the imbalance of economic development and uneven educational resources [43]. Moreover, staffing remote schools with high quality teachers is a challenge [44]. Shortage in qualified teachers and uneven teaching resources in rural education can constrain students’ achievements and inhibit inclusive education development [45]. Classroom instructional quality is critical to enhancing students’ domain-specific learning processes [46]. Designated key high schools with better academic resources play a significant role in improving scores of Chinese high school students [6]. In this respect, the school context is regarded as a strong predictor in students’ secondary education [47]. Nevertheless, these high-quality educational resources in the school context remain relatively scarce in rural regions, which may be one of the reasons that the participating students are stagnant in overall academic performances.

Furthermore, another interpretation may be attributed to family background. Students’ academic performance is found to be largely influenced by parental involvement, parental education level and family socioeconomic status (SES) [48,49,50]. Parents from low-SES families may not be able to afford educational costs. They personally have limited educational backgrounds and may not be able to actively partake in their children’s upbringing, which in turn affects children’s academic development [51]. Nevertheless, based on the findings of Mei et al. [52], more than half of students from rural secondary schools in Western China were “left-behind” children, who were consequently in lack of parental involvement in their education. Similarly, most of the participants in the current study were “left-behind” students from low SES families. In all, the stalled academic progress found in our study could be attributed to multifaceted factors concerning the school context and family backgrounds. These realities may have plagued rural education and affected students’ achievement at the school or societal level, which possibly results in the insignificant group effect and the stagnant test scores across grade levels.

With regard to the second research question, the results showed variations in individual content areas. On one hand, 11th graders only outperformed 12th graders in Chinese. On the other hand, both groups performed similarly in the English reading test. It is noteworthy that 12th graders’ test scores were lower than 11th graders in physics and biology. The decrease of scores in physics and biology attested to the high demands required for domain-specific knowledge under the diversification of the gaokao system. Compared to science-related subjects, academic development seemed to be more responsive to Chinese learning. Additionally, regarding the unchanged English test scores in 11th and 12th graders, our study accorded with previous findings that English learning backward pervades in minority rural areas [53]. As suggested in her research, English teachers from rural regions still maintained a monotonous style of outdated teaching methods, which can possibly explain the stagnant scores in the last year of high school (Grade 12). Another consideration would be students’ demographic backgrounds. Participants in our study, as described above, are from ethnic minorities including 98% of Tujia. It is plausible that language learning is impeded by unsuccessful acculturation into the cultural community and use of native dialects in class. Our results, together with other previous research, indicated that students from low-SES Chinese families are subject to poor academic and reading development in rural education [53,54].

Moreover, a multitude of research on academic achievements has uncovered the gender gap in educational attainment, with boys performing better than girls in STEM-related subjects such as physics and mathematics but worse in reading [28,55]. Indeed, we observed a decline of performance in science-related subjects including physics and biology, which was mainly caused by the underachievement of female 12th graders. Our research further confirmed a gender gap unfavorable to female students on three of the four tested subjects. To begin with, although our analysis showed no main effect of gender on results in subjects, we found the interaction effect of gender and grade. Boys outperformed girls in physics and biology test scores in Grade 12. Notably, the significant drop in test scores of physics and biology indicated that girls’ performances plummeted and fell far behind boys’ academic performances. This is consistent with previous findings on STEM academic performance that male students are better achievers in subjects of natural sciences [28]. On the other hand, our results also demonstrated that male students improved more in Chinese reading scores while the progress for female students was slower than expected, which contradicted with the prior findings that female students excelled in reading and literary tests [7,56]. Nonetheless, it should be noted that all participants were enrolled from a geographically remote and impoverished county. One possible explanation for the disadvantage of female students over their male peers pinpoints the distinct challenge in rural education. The sobering reality is that girls are more burdened with family chores in rural settings [57] and that traditional attitudes about gender roles and responsibilities may still remain in Chinese rural regions [58]. In general, from our interactional analysis, male students were found to be more academically capable than female students in most of the academic test scores. Our findings demonstrated that gender discrepancy can be a pronounced issue in rural education. As other studies suggested, rural female students may be the lowest-achieving group in terms of academic achievement [28], and that male students may have an edge over female students, especially in science-related subjects.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This cross-sectional research yielded some empirical findings regarding Chinese rural high schools’ academic performances. Specifically, our assessments suggest that academic performances reach a plateau in Chinese, English, physics and biology subjects before Grade 12. Further, the decline of scores in science-related domains was visible and significant. The status quo was challenging for rural high school girls who tend to be low achievers in high school education. The present study highlights the education dilemmas that rural students are encountering in their post-compulsory learning, however, the underlying reasons appear to be multifaceted. We should remain alert to the potential sobering reality in Chinese rural secondary education that students’ academic progress may stagnate due to the lack of resources. The stagnant progress of academic achievements may represent the fact that quality of education in rural communities is only half the battle, and more efforts need to be made to break the educational bottlenecks. The goal of inclusive and equitable quality education proposed in ESD is far from being met, especially in rural high school education. In addition to theoretical and practical implications, there are also some limitations in this study that warrant further investigations. To begin with, the sample size in this study was small. Participants in our study were exclusively enrolled from a county school in one province, which cannot represent the whole student population in rural China. The research findings with regard to generalization should be taken with caution. Therefore, more large-scale studies are needed to examine sustainable rural education in Chinese impoverished areas. In future research, we hope to involve larger sample sizes from varied rural regions in China to verify the empirical evidence. Secondly, the cross-sectionality of the current study did not allow us to trace the developmental progress of students’ academic performance. In future research, more longitudinal research based on academic assessments is needed to track the growth curve of students’ academic performance and identify their learning problems in underdeveloped rural areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; software, X.C.; validation, L.C.; formal analysis, X.C.; investigation, L.C.; resources, L.C.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., X.C.; visualization, X.C.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No.:2017ECNU-HLYT007).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by East China Normal University Committee on Human Research Protection Standard Operation Procedures (protocol code HR 252-2020, 7 May 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UNESCO. Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development (2015–2019). Available online: ps://en.unesco.org (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 (A/RES/70/1). 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2018. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Wulff, A. Introduction: Bringing out the Tensions, Challenges, and Opportunities within Sustainable Development Goal 4. In Grading Goal Four; Brill Sense: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Fu, N.; Pan, Y. Progress and Challenges of Upper Secondary Education in China; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. The Causes and Countermeasures of the Cliff-like Falling of Physics Grades of High School Students. Middle Sch. Phys. Teach. Ref. 2019, 48, 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Peng, S.; Yuan, Y. Key high schools, school investment and student academic performance. World Econ. Pap. 2017, 3, 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, G.N. Accounting for the gender gaps in student performance in reading and mathematics: Evidence from 31 countries. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2008, 34, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twelfth CPC Central Committee. The Decision of the CPC Central Committee on the Reform of the Economic System. 1984. Available online: http://news.xinhuanet.com/ziliao/2005-02/07/content_2558000.htm (accessed on 17 January 2014).

- UNESCO. China: National Plan for Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development: 2020; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; Available online: https://uil.unesco.org/document/china-national-plan-medium-and-long-term-education-reform-and-development-2020-issued-2010 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Yue, A.; Tang, B.; Shi, Y.; Tang, J.; Shang, G.; Medina, A.; Rozelle, S. Rural Education across China’s 40 Years of Reform: Past Successes and Future Challenges. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2018, 10, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Xue, J. Education inequality between rural and urban areas of the People’s Republic of China, migrants’ children education, and some implications. Asian Dev. Rev. 2015, 32, 196–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Population Status of Children in China in 2015: Facts and Figures; UNICEF&UNFPA: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.; Park, A. Education and poverty in rural China. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmer, D. The Structure of social Disparities in Education; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2268; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, H.; Zhang, L.; Luo, R.; Shi, Y.; Mo, D.; Chen, X.; Rozelle, S. Dropping out: Why are students leaving junior high in China’s poor rural areas? Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2012, 32, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. The household registration system and rural-urban educational inequality in contemporary China. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 44, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Smyth, R. Measuring regional inequality of education in China: Widening coast–inland gap or widening rural–urban gap? J. Int. Dev. 2008, 20, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X. Exploring of Educational Development and Educational Equality in the Urban and Rural Areas of China: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Three Recent Nationwide Population Censuses. Econ. Educ. 2016, 3, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum, E. Poverty and basic education in rural China: Villages, households, and girls’ and boys’ enrollment. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2003, 47, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.; Mason, M. Why do primary school students drop out in poor, rural China? A portrait sketched in a remote mountain village. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2012, 32, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, W.F. Geography of opportunity: Poverty, place, and educational outcomes. Educ. Res. 2008, 37, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.L.; Newman, J.H.; Gaddy, B.B.; Dean, C.B. A look at the condition of rural education research: Setting a direction for future research. J. Res. Rural. Educ. 2005, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Loyalka, P.; Rozelle, S.; Wu, B. Human Capital and China’s Future Growth. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lewin, K. School Mapping and Boarding in the Context of Demographic Change in Rural Areas. In Two Decades of Basic Education in Rural China; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Guo, Y.; Beckett, G.; Qing, L.; Guo, L. Changes in Chinese Education under Globalisation and Market Economy: Emerging Issues and Debates. Comp. A J. Comp. Int. Educ. 2013, 43, 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, G.; De Lian, C.; Higgins, L. The university entrance examination system in China. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2007, 31, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Education development in China: Education return, quality, and equity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Gender gap in mathematics and physics in Chinese middle schools: A case study of a Beijing’s district. Urban Rev. 2017, 49, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, F.; McElvany, N.; Trendtel, M. The school age gender gap in reading achievement: Examining the influences of item format and intrinsic reading motivation. Read. Res. Q. 2015, 50, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGeown, S.; Goodwin, H.; Henderson, N.; Wright, P. Gender differences in reading motivation: Does sex or gender identity provide a better account? J. Res. Read. 2012, 35, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M.C.; Conradi, K.; Lawrence, C.; Jang, B.G.; Meyer, J.P. Reading attitudes of middle school students: Results of a US survey. Read. Res. Q. 2012, 47, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Peng, S.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y. Who is leading in the academic competition? A study of gender differences in academic performance. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2016, 3, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Makarova, E.; Aeschlimann, B.; Herzog, W. The gender gap in STEM fields: The impact of the gender stereotype of math and science on secondary students’ career aspirations. In Frontiers in Education; Frontiers: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 4, p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Hand, S.; Rice, L.; Greenlee, E. Exploring teachers’ and students’ gender role bias and students’ confidence in STEM fields. Soc. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 20, 929–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegle-Crumb, C.; Moore, C. The gender gap in high school physics: Considering the context of local communities. Soc. Sci. Q. 2014, 95, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C. Investigation on the Causes of Academic Disorders of Rural Senior Middle School Students. Master’s Thesis, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang, China. Available online: https://www.cnki.net (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Zhang, B. A Study on the Differences in English Learning Achievements between Urban and Rural Senior High School Students and Countermeasures. Master’s Thesis, Suzhou University, Suzhou, China, 2008. Available online: https://www.cnki.net (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Li, J. An Analysis of the Causes of Poor Academic Performance and Transformation Countermeasures of Rural Senior High School Students in the Minority Areas a. Master’s Thesis, Shaanxi Normal University, Xian, China, 2016. Available online: https://www.cnki.net (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Hannum, E.; An, X.; Cherng, H.Y.S. Examinations and educational opportunity in China: Mobility and bottlenecks for the rural poor. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2011, 37, 267–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Government of Yanhe Tujia Autonomous County. 2018 Statistical Communiqué on National Economic and Social Development. Available online: http://www.yanhe.gov.cn/ (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Goh, L.; Yap, V.B. Effects of normalization on quantitative traits in association test. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaumont-Walters, Y.; Soyibo, K. An analysis of high school students’ performance on five integrated science process skills. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2001, 19, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.J.; McNess, E.; Thomas, S.; Wu, X.R.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.Z.; Tian, H.S. Emerging perceptions of teacher quality and teacher development in China. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 34, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Sylvia, S.; Yang, E.; Rozelle, S. Contract teachers and student achievement in rural China: Evidence from class fixed effects. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2018, 62, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, J.; Woessmann, L. The Impact of Teacher Subject Knowledge on Student Achievement: Evidence from Within-Teacher Within-Student Variation. J. Dev. Econ. 2012, 99, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, M. Assessing instructional quality in mathematics. Elem. Sch. J. 2012, 113, 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demi, M.A.; Coleman-Jensen, A.; Snyder, A.R. The Rural Context and Post-Secondary School Enrollment: An Ecological Systems Approach. J. Res. Rural. Educ. 2010, 25, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.S.; Chaudhry, A.H.; Shafiq, M.; Berhanu, G. Factors affecting students’ quality of academic performance: A case of secondary school level. J. Qual. Technol. Manag. 2011, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Golley, J.; Kong, S.T. Inequality in intergenerational mobility of education in China. China World Econ. 2013, 21, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, M.O.; Milledzi, E.Y.; Ampofo, E.T.; Gyambrah, M. Relationship between parental involvement and academic performance of senior high school students: The case of Ashanti Mampong Municipality of Ghana. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, K.L.; Cavanagh, T.M.; Oetting, E.R. Perceived parental investment in school as a mediator of the relationship between socio-economic indicators and educational outcomes in rural America. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 1164–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Song, Q.; Wang, J. The Influence Factors and Improvement Approaches of the Academic Performance of Left-behind-Students. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2018, 38, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, D. Investigation and Research on the Core Competence of English Subject of Senior High School Students in Minority Area. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, China, 2019. Available online: https://www.cnki.net (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Gao, Q.; Wang, H.; Mo, D.; Shi, Y.; Kenny, K.; Rozelle, S. Can reading programs improve reading skills and academic performance in rural China? China Econ. Rev. 2018, 52, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexakos, K.; Antoine, W. The gender gap in science education. Sci. Teach. 2003, 70, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Balart, P.; Oosterveen, M. Females show more sustained performance during test-taking than males. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothchild, J. Gendered homes and classrooms-schooling in rural Nepal children’s lives and schooling across societies. Res. Sociol. Educ. 2006, 15, 101–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hannum, E.; Kong, P.; Zhang, Y. Family sources of educational gender inequality in rural China: A critical assessment. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).