Cultural Sustainability: Teaching and Design Strategies for Incorporating Service Design in Religious Heritage Branding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Sustainability: The Tourism Benefits of Religious Culture

2.2. Brand-Added Value: The Integrated Design and Thinking of Religious Culture

2.3. Service Experience: Service Design Perspective Based on Religious Culture

2.4. Teaching Practice in Religious Heritage Branding

3. Methods

3.1. Research Framework

3.2. Research Scope and Participants

3.3. Research Methods and Instruments

3.4. Implementation Method and Data Collection Method

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Feedback on Learning Effectiveness: Discovering Culture and Improving Professional Competency

- Gongfan Temple Guidebook

- 2.

- Sandalwood for Seeking Blessings

- 3.

- Magnifying Glass

“By chatting with them, we were able to let them comfortably discuss anything with us. Although we didn’t necessarily get anything out of it, [the interaction] definitely allowed us to identify with the place and better understand its unique characteristics.”(P2)

“When [I was] at Gongfan Temple, there was a person who eagerly shared the temple’s history and story, explaining the buildings and culture as well as the design of the building.”(P6)

“My happiest moments during the process were the interviews and observations because I had the opportunity to engage with different people and hear their stories during our interactions.”(P8)

“When planning products intended for seeking blessings, it is important to consider local environmental resources in order to facilitate development of the surrounding environment.”(P5)

“[I] heard the stories behind each temple culture. Temples are the root of Taiwanese culture. Only by exhausting all efforts to preserve meaning can a culture be passed down through generations.”(P7)

4.2. Service Design Use: Transforming Problems to Design Performance

4.3. Discovering Design Elements: Interpreting and Recreating Traditional Codes

4.4. Introducing Culture into Courses: Towards Sustainability Branding

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Interior ROC. Nationwide Temple Statistics (Including Temples Owned by Foundations). Available online: https://religion.moi.gov.tw/ChartReport/Index?ci=1&cid=2 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Iliev, D. The evolution of religious tourism: Concept, segmentation and development of new identities. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, T.T. Preface-the essence of service design and process tools. J. Des. 2014, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Løvlie, L.; Downs, C.; Reason, B. Bottom-line Experiences: Measuring the Value of Design in Service. Des. Manag. Rev. 2010, 19, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.S.; Sung, T.T. The Development of Academic Research in Service Design: A Meta-Analysis. J. Des. 2014, 19, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, M.; Keesing, R.M. Cultural Anthropology: A Contemporary Perspective; Wadsworth Publishing: Belmont, CA, USA, 1989; Volume 54, p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Warnier, J.P. La Mondialisation de la Culture; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chu-Shore, J. Homogenization and Specialization Effects of International Trade: Are Cultural Goods Exceptional? World Dev. 2010, 38, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S. The Future I have Seen; Common Wealth Magazine: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture ROC. 2016 Summary Report of Cultural Tourism Output Estimates. Available online: https://stat.moc.gov.tw/Research_Download.aspx?idno=1112 (accessed on 10 March 2020).

- Goeldner, C.R.; Ritchie, J.R. Tourism: Principle Practice, Philosophies, 11th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rinschede, G. Forms of religious tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukonić, B. Medjugorje’s religious and tourism connection. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The Impact of Culture on Tourism; OECD: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.-H.; Ling, Y.; Lin, J.-C.; Liang, Z.-F. Research on the Development of Religious Tourism and the Sustainable Development of Rural Environment and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rahman, I. Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and des-tination loyalty. Tour. Manag. Perspect 2018, 26, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, J.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The Service Experience in Tourism. In Tourism Management: Towards the New Millennium; Ryan, C., Page, S., Eds.; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, N.; Halpenny, E. The role of cultural difference and travel motivation in event participation: A cross-cultural perspective. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2019, 10, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liat, C.B.; Nikhashemi, S.; Dent, M.M. The chain effects of service innovation components on the building blocks of tourism destination loyalty: The moderating role of religiosity. J. Islam. Mark. 2020. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugini, A. Religious tourism and Sustainability: From Devotion to Spiritual Experience. In Tourism in the Mediterranean Sea; Grasso, F., Sergi, B.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.H.; Hsieh, D.W. Discussion on the Cultural and Tourism Value of Religions. Buddhism Sci. 2010, 11, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lash, S.; Urry, J. Economies of Signs and Space; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin, J. The Age of Access: The New Culture of Hyper Capitalism-Where All of Life is a Paid-For Experience. Radic. Teach. 2002, 63, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Saco, R.M.; Goncalves, A.P. Service Design: An Appraisal. Des. Manag. Rev. 2010, 19, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.L.; Lu, M.T. Influence of Product Form Attributes on Visual Complexity and Consumer Preferences. J. Des. 2019, 24, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R. The Dream Society: The Coming Shift from Information to Imagination; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Verganti, R. Design-Driven Innovation-Changing the Rules of Competition by Radically Innovating What Things Mean; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney, M.; McFarland, J.; Yoon, G.H.; Hardy, T. Global Localization, Innovation—Global Design and Cultural Identity, Summer, 46–49; 2002. Available online: https://www.idsa.org/sites/default/files/xiglafiles/summer02_samsung.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Moalosi, R.; Popovic, V.; Hickling-Hudson, A. Product analysis based on Botswana’s postcolonial socio-cultural perspective. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson, P. Brand orientation in the charity sector: A framework for discussion and research. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2001, 6, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.M. Exploring a Missing Link for the Brand Image Effect on Brand Loyalty: The Mediated Path of the CAC Extending Model. J. Manag. 2017, 34, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-K.; Lee, T.J. Brand Equity of a Tourist Destination. Sustain. J. Rec. 2018, 10, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daldanise, G. From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement. Sustain. J. Rec. 2020, 12, 10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarstefano, G.; Gristina, S. Eco-Sustainable Routes and Religious Tourism: An Opportunity for Local Development. The Case Study of Sicilian Routes. In Tourism in the Mediterranean Sea; Grasso, F., Sergi, B.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sangiorgi, D. Transformative services and transformation design. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, S. Service Design: Practical Access to an Evolving Field. Unpublished. Master’s Thesis, Köln International School of Design, Cologne, Germany, 2005. Available online: https://uploads.strikinglycdn.com/files/280585/5847bd6a-e928-4f0f-b677-ed7df26fa1df/Practical%20Access%20to%20Service%20Design.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Yang, C.F.; Sung, T.J. Service design for social innovation through participatory action research. Int. J. Des. 2016, 10, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, P.N. Historic Cities, Representation of Architecture and Cultural Tourism: A Case Study on Tang Paradise in Xian City, China. J. Des. 2011, 16, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Clatworthy, S. Service innovation through touch-points: Development of an innovation toolkit for the first stages of new service development. Int. J. Des. 2011, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C. Religious Tourism and Research in Taiwan: An Approach of Essentialism and Methodology. Yu Da Acad. J. 2011, 27, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hollins, G.; Hollins, B. Total Design: Managing the Design Process in the Service Sector; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, T.; Littman, J. The Ten Faces of Innovation: IDEO’s Strategies for Beating the Devil’s Advocate & Driving Creativity Throughout your Organization; Currency/Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-E.; Liu, C.-H. The creative experience and its impact on brand image and travel benefits: The moderating role of culture learning. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janonis, V.; Virvilaitė, R. Brand image formation. Eng. Econ. 2007, 2, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

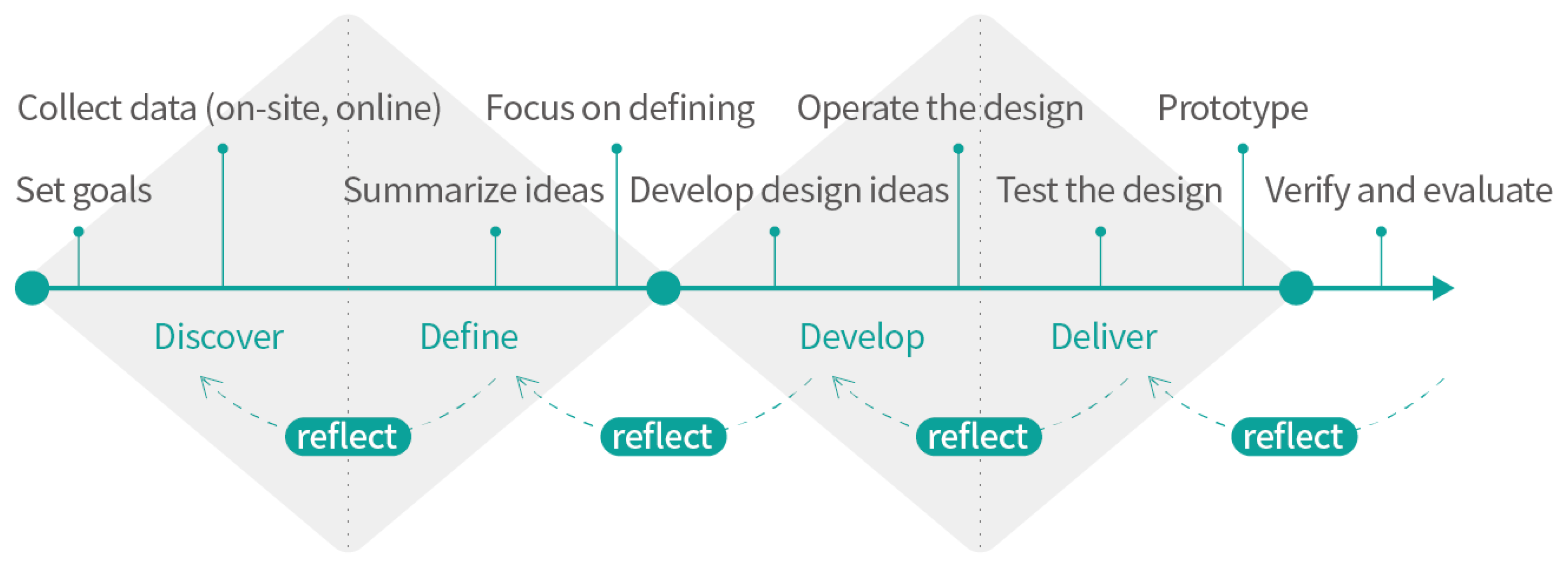

- Design Council. The Design Process: What is the Framework for Innovation? Design Council’s Evolved Double Diamond. Available online: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/design-process-what-double-diamond (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Chang, T.Y.; Wen, C.T. Cultural Authenticity in Culture-Driven Products: The Communication of Cultural Messages. In Pioneering Minds Worldwide: On the Entrepreneurial Principles of the Cultural and Creative Industries; Hagoort, G., Thomassen., A., Kooyman, R., Eds.; Eburon Academic Publishers: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 146–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, T.Y.; Wen, C.T. Discover the Root: Construction of Authenticity in Culture-Driven Products. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 311, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Content | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Focus | Field investigation Service design tool application Design methods | Creative thinking Design methods Communication | Industry practices Design proposals |

| Design Implementation Focus | Religious service touchpoint design | Design thinking and ideation | Integrated design Implementation of industry–academic collaboration projects Design marketability |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, T.-Y.; Chuang, Y.-J. Cultural Sustainability: Teaching and Design Strategies for Incorporating Service Design in Religious Heritage Branding. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063256

Chang T-Y, Chuang Y-J. Cultural Sustainability: Teaching and Design Strategies for Incorporating Service Design in Religious Heritage Branding. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063256

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Tsen-Yao, and Yu-Ju Chuang. 2021. "Cultural Sustainability: Teaching and Design Strategies for Incorporating Service Design in Religious Heritage Branding" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063256

APA StyleChang, T.-Y., & Chuang, Y.-J. (2021). Cultural Sustainability: Teaching and Design Strategies for Incorporating Service Design in Religious Heritage Branding. Sustainability, 13(6), 3256. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063256