Abstract

Profiles of millennial reviewers and gamification can contribute to digital sustainability as a driver of innovation and growth. The study aims to detect if there are profiles of reviewers that can be grouped together, in order to apply a specific gamification to them and to make it sustainable over time. In this way, more information will be generated through the reviews that will help responsible consumers to choose better in their purchase decisions. The objective of this study is twofold. First, it aims to characterize online product reviewers based on their intrinsic motivations and self-perception when they comment, identifying their main motivations. Second, it aims to classify these individuals based on the acceptance of gamification elements while commenting on and relating them to the intrinsic attributes that determine their behaviors. A survey method design was used to capture responses from 187 millennial reviewers of Amazon in Spain. The relationships between motivations and the types of reviewer were extracted from the accommodation of the dataset using decision trees (DTs), specifically, the J48 algorithm. To contribute to the second objective, this paper elaborates a typology of reviewer analysis based on cluster analysis and DTs. It is confirmed that online product reviewers can be characterized based on their intrinsic motivations, which are mainly egoistic motives, competence and social relatedness. The obtained results show that the J48 DT provides excellent classification accuracy of approximately 95% in identifying reviewers based on intrinsic motivations. Similarly, egoistic intrinsic motives are decisive in focusing gamification strategies.

1. Introduction

Online consumer reviews are having an increasingly high impact on e-commerce and digital sustainability. We define digital sustainability as the organizational activities that seek to advance the sustainable development goals through creative deployment of technologies that create, use, transmit, or source electronic data as, for example, gamification [1]. In this line, digital sustainability technologies can be broadly defined as electronic tools, systems, devices and resources that generate, store or process data in their business models to leverage social and environmental value creation [2]. They manifest in the form of three distinct, but related, elements—digital artifacts, digital platforms and digital infrastructures [3]. Many studies contribute to explaining why digital sustainability remains—and always will remain—a contested concept [4] and according to many scientific studies little evidence exists, so far, for a genuine contribution of digital paradigms to sustainability and besides, their role in tackling the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) remains barely explored. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) within the United Nations 2030 Agenda emerged in 2015, becoming an unprecedented global compass for navigating extant sustainability challenges. Nevertheless, it still represents a nascent field enduring uncertainties and complexities. In this regard, the interplay between digitalization and sustainability unfolds bright opportunities for shaping a greener economy and society, paving the way towards the SDGs [5]. In this aspect, reviewers through online reviews could be a key factor and of great use to facilitate pursuing the SDGs [6], through enhanced analytical capacities, collaborative digital ecosystems and better knowledge of their profiles. Reviews are autonomously updated by customers themselves and they are perceived as a sustainable form of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) [7]. Prior studies suggest that reviewers desire to make an impact on the world [8,9] and that they make this impact by helping other consumers choose the best products [10]. Customer reviews have a strong influence on consumers’ purchase decisions, and they impact product sales [10,11,12]. In fact, online reviews help consumers to avoid bias in their understanding of products and allow for the formation of evaluation criteria, minimizing the cognitive costs associated with these choices [13]. According to consumer surveys, they trust opinions and comments posted on the web, and 88% of customers read online reviews before making purchases [14]. A typical online review consists of a short text of more detailed information about the consumption experience and about the product, and it normally includes a numeric star rating summarizing the product evaluation. When the average rating score increases, or a favourable review is added, it could have a positive impact on product sales [15,16]. However, knowledge about reviewers and their motivations remains limited.

Online reviewers have become a form of consumer engagement [17], occurring when they voluntarily generate reviews within a controlled reviewing platform. This research is focused on volunteer reviewers and is based on the motivators of engagement starting from self-determination theory [18]. Gamification is the application of game-design elements to non-game contexts [19]. It has mainly been applied in the areas of business and commerce [20,21]; marketing and advertising [22]; education [23,24]; health [25]; environmental behavior [26]; and social change [27].

The effect of gamification has become a popular research topic in recent years [28]. Gamification tools are used on e-commerce web pages to encourage users to generate content, to motivate them and to promote engagement and user loyalty [29]. Important companies worldwide, such as Amazon or eBay, are taking advantage of the potential of game elements for these purposes. In particular, this work aims to analyse the user profiles on the e-commerce platform www.amazon.es (accessed on 3 November 2019). Amazon uses a reputation points system (RPS) that reflects the results of users’ actions as reviewers. The “online reputation” generated is key for the impact of online reviews because, for the user, not only is what is said very valuable but also who says it [30]. In this sense, e-commerce companies are concerned that motivated reviewers make more comments of higher quality, resulting in building their reputations.

This research expand the focus in e-commerce, looking at how gamification can be used for the generation of quality content, increasing information, and details about products and helping consumers to consume more responsibly. Detecting groups of individuals and the characteristics that identify them will allow to apply gamification in a customized and specific way to each type of reviewer. Gamification would be managed in a more reasonable, sustainable and focused way for those individuals who are more receptive. This will avoid annoying reviewers who do not like gamification or whom it affects differently, being able to change the game elements for these typologies. Besides, more respectful and better-oriented gamification will be used towards the reviewer. On the other hand, customers respond more positively to attribute-based online reviews for searched products [31]. If the attributes are well-defined thanks to the good work of the reviewers, they will allow the most sustainable products to be detected by responsible consumers [32,33,34].

In this line, social, ethical and environmental issues arising from the acquisition of products and services are increasingly considered in purchase and consumption behavior. This is what has come to be called socially responsible consumption. The study and analysis of this behavior, closely linked to the individual’s conscience, should be of great interest since it enables us to learn how to evolve the traditional consumption patterns and reflect upon its consequences. In this way, it could facilitate both policies of social intervention and the design of business strategies for companies wishing to connect with consumer values and give them greater satisfaction [35].

Business-to-consumer (B2C) e-commerce continues to increase exponentially annually in Spain. Millennials, also called Generation Y, are digital natives and are accustomed to using technology in a natural way. Currently, 21.37% of online purchases are generated in Spain by them in 2019 [36]. Millennials know well the game elements used in gamification, given their familiarity and contact with video games. A characteristic of gamers, and therefore of millennials, is their facility in reaching a state of flow. One study of more than 2000 users in U.S. revealed that 85% of millennials write online reviews after a standout experience [37]. The high connectivity, the detailed information about the products that they have and the great collaborative efforts of the millennials indicate that, in general, their comments have a greater impact and reach more than those of other consumers. At the same time, young people are more likely to be market mavens, and they are eager to share their comments [38], making them fantastic brand advocates and a very valuable segment for study.

Although the research concerning millennials, e-commerce and online reviews has been extensive, there has been surprisingly little written about relating the profiles of individual reviewers and gamification. Expanding on previous studies of types of profiles, in which classification algorithms have grouped individuals into clusters [39], the classification of reviewers of this study also regards how they consider themselves. That is, in addition to the information obtained about their motivations, individuals choose the class of reviewer that best defines them, thus checking whether their motivations coincide with the chosen class. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no research studies relating these intrinsic motivation variables to profiles that evaluate the selected gamification elements. The purpose of our study is to examine the characteristics of millennials with regard to their motivations and gamification. Specifically, three research questions are examined:

Could millennial online product reviewers be characterized based on their intrinsic motivations? What intrinsic motivations would mainly serve to identify them?

Can intrinsic and extrinsic motivations, such as gamification, be associated with groups of individuals with similar characteristics?

Can gamification elements be targeted to specific profiles, or should they be implemented generically?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Online Reviewer Motivation

Reviewing communities are a type of service environment in which the co-creation value is a result of interactions among people, technology and the information shared [40]. Researchers have differentiated behaviors in online communities depending on participant competence, social relatedness and permanence over time [39,41]. Consumer groups operate independently in social media environments based on underlying motives. These motives include intrinsic motives associated with the desire for identification or interaction with others and altruistic or egoistic motives [42].

The motivations of individuals have been widely studied through self-determination theory [43], which was developed later by [44]. The SDT has its roots in psychology; it follows [45] hierarchy of human needs and differs from other theories in that it studies motivations by type and not by quantity. This theory covers the motivations of the individual studying different possibilities of motivation, differentiating between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Intrinsically motivated behaviors refer to those performed for the mere satisfaction of doing them, without the need for external incentives or results. Intrinsically motivated individuals become engaged in activities because they bring them enjoyment or are fun or interesting [43]. In contrast, extrinsically motivated behaviors are performed expecting a separate benefit, such as a reward [46]. The SDT is based on three psychological needs: autonomy, competence and social relationships [44,47]. Autonomy refers to the feeling of having freedom of action and being able to make one’s own decisions. Increasing the options and possibilities of choices of a user will increase his or her intrinsic motivations. Competence consists of the human being’s need to feel that they have the possibility to practice their skills and improve them [48]. Positive feedback on a task would increase the user’s intrinsic motivation [49]. Finally, social relatedness refers to being connected with other people and the feeling that the individual occupies a place in society. If the three needs are satisfied when performing an activity, intrinsic motivation increases, while in the opposite case, states of anxiety or anger might appear, affecting motivation [18,50,51]. Recent studies have confirmed that the greatest contributors to enjoyment of games are autonomy, competence and social relationships, regardless of the content, type or genre of the game [50,52]. Conversely, certain studies have shown that extrinsic motivation is autonomously associated with greater engagement, achieving lower abandonment rates and better levels of development in tasks [44]. By analogy with games, the combination of these motivations would be present in gamified environments.

Other authors, such as [53], have categorized motivations into egoist (reputation and reciprocity), altruistic (enjoyment of helping others), collectivist and principalistic motives. Reviewing activities are framed in market helping behavior, in which altruistic and egoistic motives are present [54]. Altruism is one of most significant motives for consumers’ willingness to share online in the absence of tangible returns [54,55]. At the same time, the need to help society and the community favours eWOM (electronic word-of-mouth) activity. In contrast, egoistic helping motives are associated with hedonistic rewards and show a desire for reputational enhancement and self-gratification [53]. In this research, egoistic motives are defined in terms of desire for social recognition, reputation or attraction of attention.

Research has found engagement types in reviewing communities depending on longevity of contribution [39]; participant competence (e.g., novice vs. expert; [41]), and social relatedness (e.g., tourists, devotees and insiders; [56]). These include egoistic motives, altruistic concern about others and intrinsic motives.

2.2. Gamification

To influence the behavior of individuals in e-commerce, a multitude of gamification elements are used, such as points, badges, leaderboards, levels, competitive bidding systems, real-time feedback and progress bars [57,58]. It is very common to find a set of gamification elements called PBL points, badges and leaderboards; [59]. Points influence the status of the user and affect their reputation based on the assessments of other users. The reputation points system (RPS) is the most complex system, and it reflects the degree of integrity and consistency of a user [60]. Reputation is the perception by others or the inferred external image of the individual [61]. Obtaining the confidence of the user to purchase sustainable products on the e-commerce page is essential, since online environments involve situations of uncertainty and generate a perception of vulnerability [62]. Besides, the reviewer reputation is associated and is positively correlated to review helpfulness [63]. Amazon’s RPS harnesses the useful votes that are received in the form of points and the percentage of the utility of the comments that are made by the user. These scores, the badges obtained when commenting and the position that a user occupies in a ranking of opinions (leaderboard) are shown in the user’s profile.

The use of gamification elements, such as badges and rankings, is particularly recommended to maximize engagement and other user activities in e-commerce [64]. Reviewers are part of the rankings when they comment, becoming empowered consumers [65]. They engage in helping the market in an altruistic form or can satisfy their egoistic desires or intrinsic motivations [42,54]. Amazon.com’s top reviewer community uses a public ranking system to motivate, recognize and influence reviewer behavior.

Player typologies and game research provide points of departure for studies outside what can traditionally be seen as games [20]. One of the main theoretical theory adopted in gamification research is that of self-determination [28,66,67] which can lead to autotelic behaviors [68, 69] point out four gaming motivations: control, context, competency and engagement. In recent years, researchers have employed a five-factor model to understand the psychological and behavioral natures of video game users [70,71]. It was determined that users’ experiences of video game playing, such as competence, immersion and autonomy, are associated with personality traits including agreeableness, extroversion, conscientiousness, openness and emotional stability [70, 72] mention six motivations including competition, challenge, social interaction, diversion, fantasy and arousal. In short, it is observed that there are a multitude of psychological variables of the players that are associated with gamification.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Sample, Research Context

In this research, a questionnaire was used and administered as a pretest to a sample of 30 individuals, which was extended to a sample of 187 Spanish nationals. The survey was conducted by an investigation team consisting of three experts in market research from the University of Córdoba and Loyola Andalucía University. The data sample was obtained through purposive sampling in which individuals were selected due to their expertise on the field. In this regards, all participants were frequent reviewers, with a positive attitude towards responsible consumption and have shown their interest in its own ranking. In this regards, the sample is representative of the population under study (avoiding a potential bias in the recruitment process). The individuals were invited to participate in the study via email (in June 2019). The recruitment process and the study were approved by the Ethical Committee of the university. Specifically, the sample selected consisted of millennial e-commerce users who visited the www.amazon.es webpage during the week prior to the questionnaire (the second week of December 2019) and who wrote reviews of products during the 12 previous months on the web with a personal computer, thus ensuring direct contact with the elements of gamification. All of the participants declared that they agreed with the fairness of the public ranking of Amazon. The sample universe was distributed to 52.4% of Spanish men and 47.6% of Spanish women born between 1984 and 2001. Regarding the level of studies, 64.1% had university or higher education, and 62.03% of those surveyed were working. Information about the demographic profile of the sample is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the sample.

3.2. Instrument and Measures

A survey was used to gather information. The development of the instrument was based on a literature review to identify the characteristics of individuals: motivations and acceptance of gamification. The research instrument consisted of six variables. In relation to intrinsic motivations, five variables were considered: autonomy, competence, social relatedness [44,73], and altruistic and egoistic motives [9,74]. For the study of gamification, the PBL triad (points, badges and leaderboards) was used [59]. The research instrument consists of 25 items and the sources are shown in the Appendix A (Table A1).

A Likert scale was used to evaluate the responses to the elements. Likert scales measure the degree of acceptance or rejection of the presented statements. All of the items were 7-point Likert-type items ranging from 1 for “strongly disagree” to 7 for “strongly agree”. Additionally, some questions were asked about the importance of reading reviews and the evaluation of other users, the frequency of writing reviews, and familiarity with video games.

Additionally, the participants were asked to choose a single class that best defined them as reviewers among three alternatives based on their perceived psychological need fulfilment and their degree of altruism or selfishness, following [9]. However, unlike these authors, when using egoistic motives, the questionnaire focused on the egocentric personality of the individual, leaving the perception of the community rank aside to analyse it later along with the rest of the gamification elements (points and badges).

3.3. Data Analysis

It is important to mention that additional experiments with other machine learning models were also performed (Bayesian networks, logistic regression, or neural networks among others). In those experiments, it was obvious that linear models were not able to reflect non-linear relationships among input variables, which is necessary for performing a robust classification of the problem under study. Within the umbrella of non-linear models, the J48 model was the one yielding the best trade-off between performance and interpretability and for that reason, it was the one employed in the empirical study.

To achieve the first objective of the research, a J48 decision tree (C4.5) was implemented to characterize reviewers based on their intrinsic motivations and their self-perception when they commented. This technique is one of the most commonly used machine learning techniques [75]. The decision trees generated by the C4.5 algorithm can be used for classification, and for this reason, C4.5 is often referred to as a statistical classifier. C4.5 is known as an evolution and refinement of the Interactive Dichotomize 3 algorithm with very good classification accuracy [76]. This method represents a simple hierarchical structure in which nodes indicate the attribute tests, and the terminal nodes show decision outcomes [77]. Classification is generally used in supervised datasets in which there is a class label for each instance, as occurred in our case of study. J48 uses splitting criteria based on the Gain Ratio (a normalized version of Information Gain) for building trees. It has both reduced error pruning and normal C4.5 pruning options. For validation, k-fold cross-validation was used. The advantage of this method is that all observations are used for training and validation, and each observation is used for validation exactly once. As pointed out in the literature, J48 is a reliable model to classify a set of nominal values into categories, unlike neural networks, which require that the input variables be continuous. In this case, all of the input variables are on a 7-point Likert scale, making the model perfect for addressing the problem and justifying the use of decision trees. In our analysis, we selected algorithm J48 with default parameters from Weka [78]. Weka is open-source software for data mining developed at the University of Waikato in New Zealand that is widely used in classification and clustering by communities of researchers.

Pursuing the second objective, a cluster analysis and a new J48 were performed. Clustering analysis creates and discovers a group of similar data items, in our case, based on the reviewers and their degree of acceptance of gamification while they are reviewing. In machine learning, there are many clustering models, and the most widely implemented is K-means. K-means is a partitioning clustering algorithm, and this technique is used to classify the given data items into k different clusters through iterations, and it tends to converge to a minimum. The outcomes of generated clusters are independent of each other [32,34,79]. This study used K-means based on Elbow Criteria to determine optimal values [80,81]. Subsequently, the decision tree was developed to detect the main characteristics of the profiles obtained and based on gamification, relating them to intrinsic motivations.

4. Results

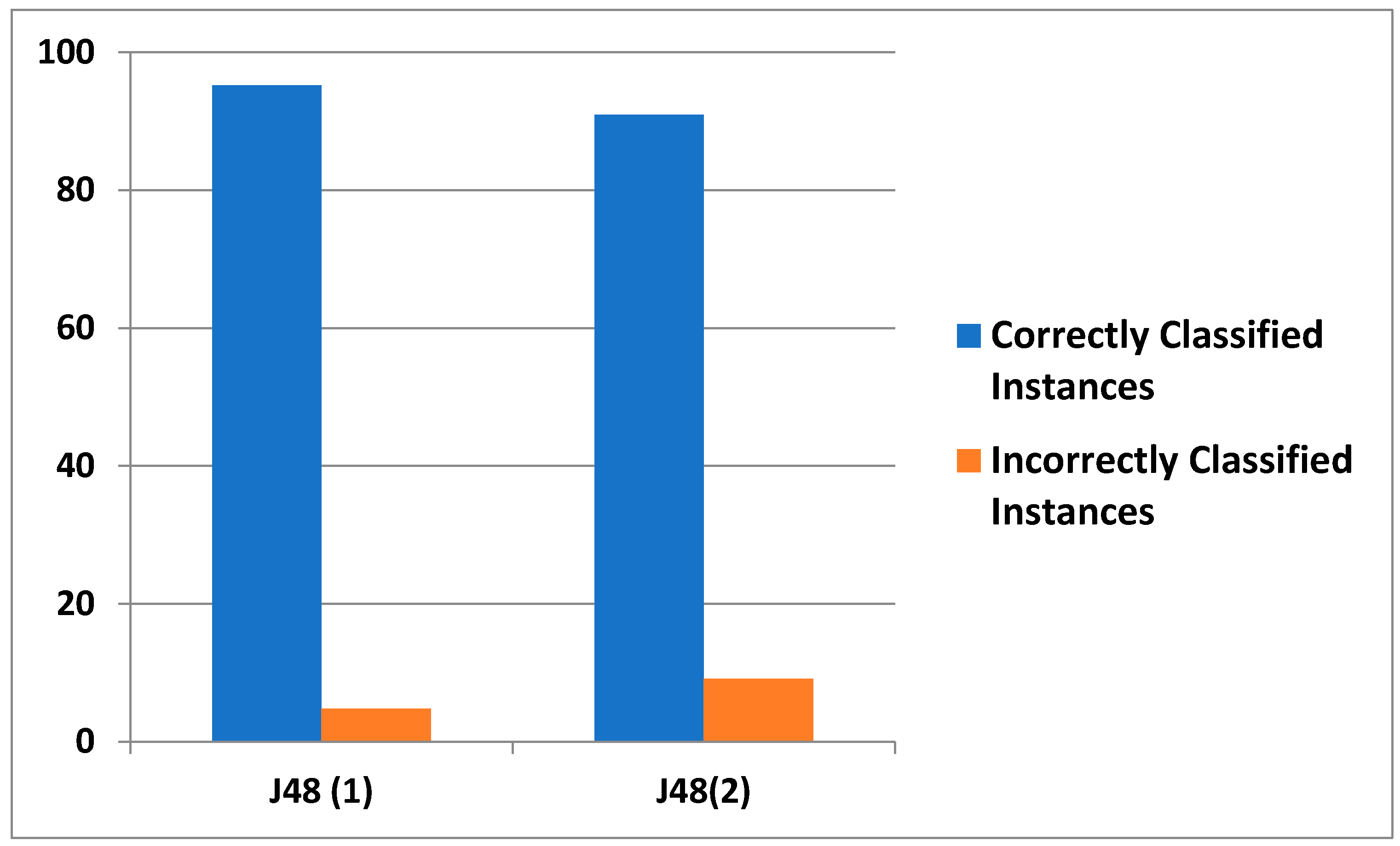

The J48 machine learning model has played a main role in fields such as engineering, climate, social sciences and medicine due to its simplicity and intuitive interpretation [82]. The main limitation of the model is its predictive power which appears to be not a problem for this case of study (as the decision tree achieve almost a perfect classification of individuals with a very simple model). The results obtained in this study are shown below. Figure 1 shows the correctly and incorrectly classified instances of classification algorithms of J48 decision trees using the WEKA tool. In both cases, it can be observed that there are very good accuracy and performance of classification algorithms for the dataset.

Figure 1.

Accuracy measure for classification algorithms.

For the first classification algorithm J48 (1), of 187 datasets supplied to the system, 178 were correctly predicted, and only 9 were incorrectly predicted. It is important to note that the global accuracy obtained by the model was 95.18%. This accuracy is quite high and guarantees very good classification of individuals. Table 2 shows the confusion matrix (C.M.) for the three-class classifier.

Table 2.

Confusion matrix of J48 (1) classifier.

The information contained by C.M. concerns the actual and predicted classifications performed by a classification system. The diagonal elements are the number of correctly classified instances. Based on the C.M., we can find the specific accuracy of the classifier as Acc1 = 0.95, Acc2 = 0.96 and Acc3 = 0.93, according to each class.

A summary of our findings is shown in Table 3, which shows the correctly and incorrectly classified instances, TP rate (true positive), FP rate (false positive), precision, recall, F-measure, receiver operating characteristics (ROC), Kappa statistics and error rates.

Table 3.

Accuracy measure and error rate of the J48 (1) classifier.

The TP and FP values (0.95 and 0.024) are optimal because they have a high degree of accuracy in positive cases and very low value in false positives [83,84] (Fawcett, 2004; Witten et al., 2009). With respect to precision, the percentage of accuracy of the model after performing the classifications is very high (0.952) [85], showing that the model measures in the best way the correctly recognized instances with respect to the total of predicted instances. In the recall results, it can be seen that they are high and favourable because the model recognizes the instances correctly in real terms. Conversely, the error rate values of RMSE, MAE and RAE obtained are 0.17, 0.03 and 8.75%, respectively. These low results reflect good fit of the model. To determine the global performance of prediction models, ROC curve analysis is used [86]. The global performance of the model is quantified as 0.970. The qualitative correlation between this value and the prediction capability of models is considered excellent if it is between 0.9 and 1 [87]. It can be concluded from the results that the developed classifier is very reliable.

The attributes chosen for classification were five intrinsic motives: autonomy, competence, social relatedness, altruism and egoism; and the predicted output for a given reviewer was one of these options—Challenge Seekers (CS), Community Collaborators (CC) and Indifferent Independents (II)—based on and adapted from [9] classification.

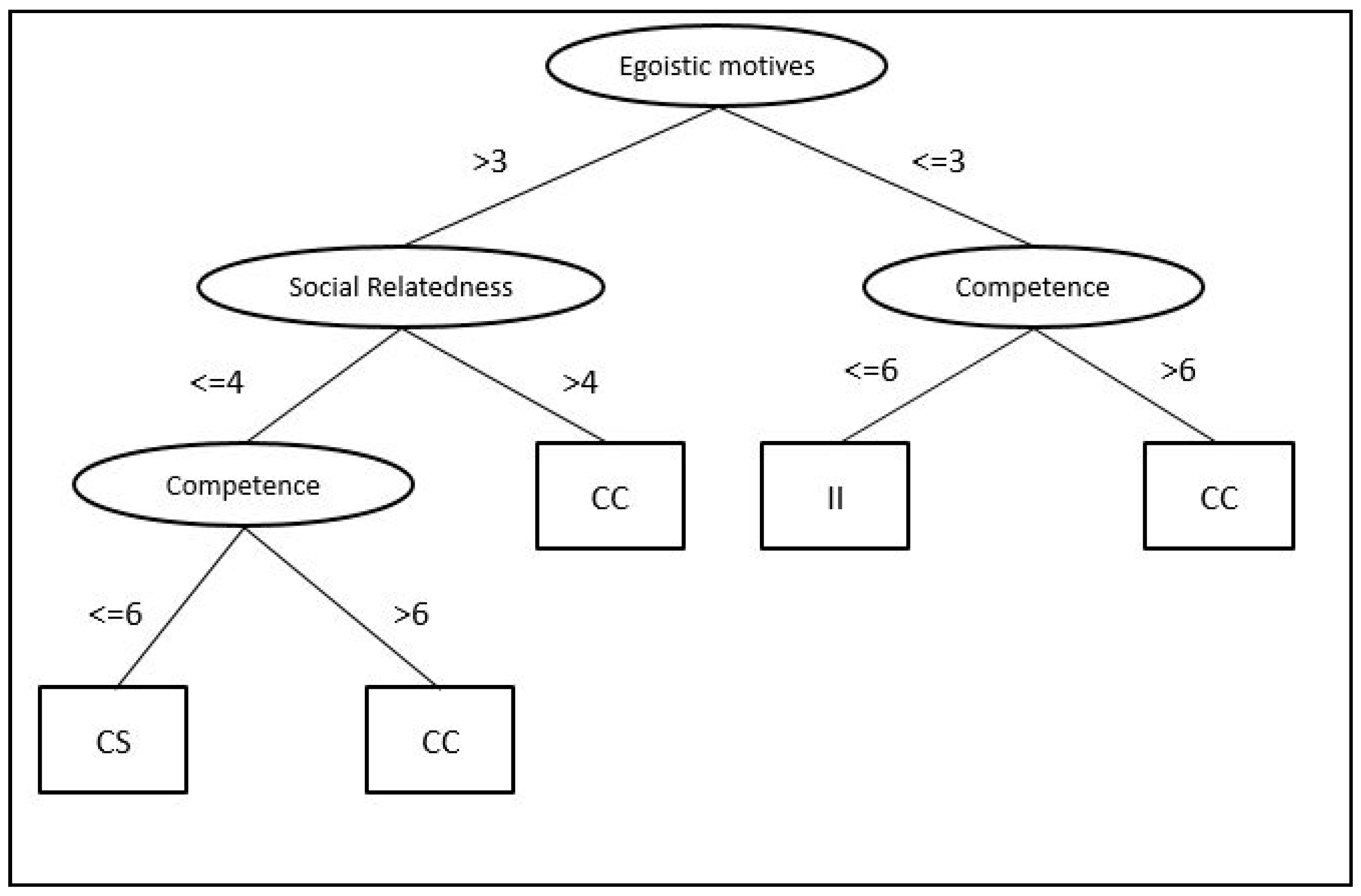

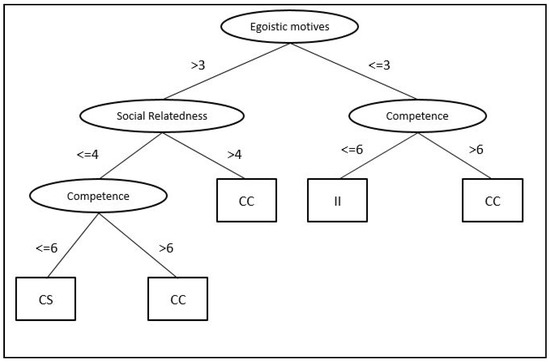

Figure 2 is the graphical representation of the generated classification tree. This data visualization shows the information clearly and efficiently. The decision tree structure consists of a root node, three internal nodes and five leaf nodes.

Figure 2.

Model classification tree (1).

Egoistic motives are the main attribute that determines the classification. Additionally, social relatedness and competence are important for classifying individuals. The rest of the attributes (autonomy and altruism) are not significant for the class assignment.

The CS class of reviewers are driven by egoistic motives and indifferent or low social relatedness, and they are not worried about having very high competence. The class of reviewers CC is the most complex, for which the casuistry is greater. In fact, CCs can be found to have three types of characteristics. The first type (CC1) exhibit egoistic motives and indifferent or low social relatedness and are very concerned about being competent. A second type (CC2) have egoistic motives and in turn want to be connected and relate to others. The third type (CC3) are not motivated by selfish motives, but they do have the need to put their skills into practice and improve them. Finally, reviewer II hardly reflects selfish motives when making comments, and they are not worried about having very high competence and developing their skills. Table 4 summarizes the values towards the decision tree nodes for each reviewer profile.

Table 4.

Values for each reviewer profile according to motivation.

To achieve the second objective, individuals were classified based on their acceptance of the gamification elements. For this purpose, a second-order gamification construct was developed, the variables of which were points, badges and leaderboards (PBL). Using the K-means algorithm and considering the Elbow Criteria, two groups were considered since the percentage of the variance explained was greater than 90% for two classes, making it unnecessary to switch to three groups. Consequently, the sample was classified into two groups of individuals based on their degree of acceptance of gamification: those who showed a positive attitude towards PBLs and those who were not attracted to such elements.

Subsequently, the groups were related based on gamification obtained with the five intrinsic motivations using the J48 algorithm (2). In this way, if the model has a good classification percentage, we understand that there is a certain relationship between intrinsic motivations and the types of individuals who are pro-gamification or anti-gamification. Below, we analyse the statistical performance of the implemented decision tree. It is important to note that the global accuracy obtained by the model is 90.90%, which in our humble opinion emphasizes the competitive performance of the implemented model. Of 187 individuals, 170 were correctly predicted, and 17 were incorrectly predicted. Table 5 shows the confusion matrix for the two-class classifier.

Table 5.

Confusion matrix of J48 (2) classifier.

In this case, the incorrect number of individuals classified as “a” with “b” (13 patterns) is higher than the erroneous ones classified as “b” with “a” (4 patterns). That is, it better classifies those patterns that have a positive attitude towards gamification. We can determine the specific accuracy of the classifier to be Acc1 = 0.965 and Acc2 = 0.819, according to class. A summary of our findings about the J48 (2) decision tree is shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Accuracy measure and error rate of the J48 (2) classifier.

The values of TP and FP (0.90 and 0.124) are very good since they present a high degree of success in positive cases and a low value for false positives. Additionally, regarding the precision of the model, the value observed is very good (0.911). In real terms, the model recognizes the instances well (recall equals 0.90). Kappa statistics (KS) determine the attribute measure of agreement. The KS value obtained (0.80) reflects fair agreement because it is near 1. The error rate values of RMSE, MAE and RAE are 0.29, 0.16 and 34.85%, respectively. Since the RMSE is less than 30%, the goodness of fit of the model is considered to be very good. The ROC curve with a value of 0.85 has good discriminating ability and is considered useful because it is between 0.7 and 0.90. In light of these results, we can conclude that the developed classifier is quite reliable.

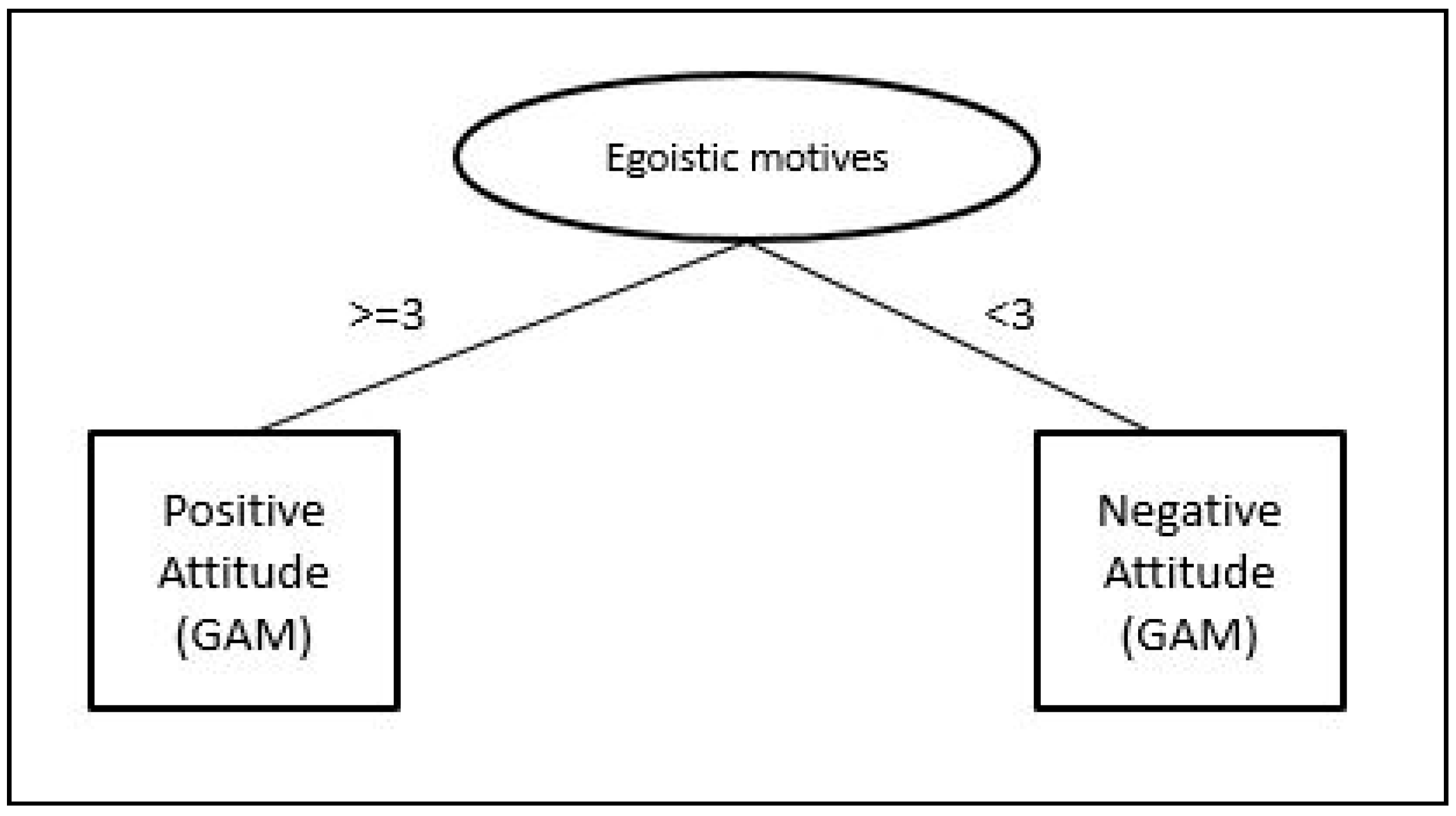

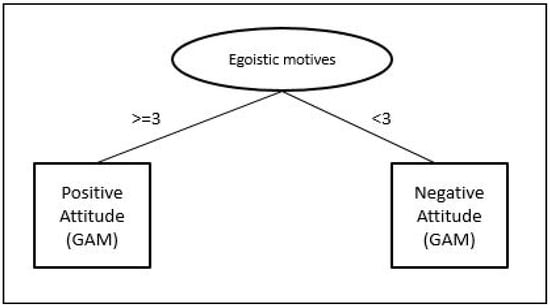

Again, the attributes chosen for classification were the five original intrinsic motives: autonomy, competence, social relatedness, altruism and egoistic motives. In this case, the predicted output is one of the two classes associated with gamification: users with positive or negative attitudes towards gamification. Figure 3 shows the decision tree structure developed. It consists of a root node and two leaves.

Figure 3.

Model classification tree (2).

It should be noted that egoistic motives are the main attribute that determines the classification. In fact, it is the only attribute relevant to the class assignment. The class of reviewers who have selfish motivations is classified as users with a positive attitude towards the elements of gamification. Even for those who declare to be indifferent in terms of selfish personality or even define themselves as not very selfish, gamification is also positive. In contrast, those who declare themselves barely or not at all selfish will tend to show a negative attitude towards gamification.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The results of this study contribute to advancing knowledge about reviewers’ motivations and gamification by highlighting the relationship between egoistic motivations and positive attitudes towards gamification elements. This section discusses the results of the classification models, addresses the limitations of the study and highlights the contributions to research and practice.

5.1. General Discussion

This study expands the research scope of gamification by focusing on e-commerce reviewers towards digital sustainability. Digital sustainability technologies have also been suggested as important tools for companies looking for sustainable solutions to global problems while reaching customers and suppliers across borders. The use of a combination of supervised machine learning techniques and gamification in this area, together with the good results obtained, opens a new path for future classification work. The differences among groups result in the need for segmentation when applying gamification in e-commerce. The first approach to characterizing millennial reviewers was based on a supervised preclassification based on three groups of reviewers from [9]. In other words, the group of reviewers is conditioned on profiles with characteristics determined a priori, and the attributes respect the original variables. In this research, the egoistic motives attribute is focused on one’s own reputation, attracting attention and a desire for social recognition. It is important to note that reputation is often cited as an important determinant of information sharing behavior [88]. The questionnaire isolates the rankings and classification tables in matters related to reputation so as not to distort the subsequent relationships with the elements of gamification. It was intended to determine the authentic personality of the individual to later observe whether it was related to extrinsic motivations, as was verified.

When classifying the reviewers, egoistic motives should be studied mainly and the attributes of competence and social relatedness considered. The decision trees allowed us to identify the determining attributes for the classification and their cut-off values. In this sense, we not only know the class of reviewers to which an individual belongs, but also, as in the case of CC reviewers, it allows us to differentiate them into three other new subcategories.

The clustering performed showed that reviewers can be classified based on their positive or negative attitudes towards gamification. By applying the J48 algorithm on motivations, the classification criterion was greatly simplified since it fell back on selfish motives. That is, if the individual presents selfish characteristics, they will be more likely to receive gamification more effectively because their attitude will be positive towards it.

Therefore, the linchpin on which the classification depends is the egoism of the individual. This statement clashes with the altruism and collaborative eagerness that millennials generally show [38,89]. In fact, the willingness to help others is one of the strongest antecedents of online review writing frequency [90], which is not to say that altruism is not important to define the characteristics of young millennials. However, to classify reviewers, it is not a relevant attribute.

Regarding the elements of gamification points, badges and leaderboards, a priori, they could have been analysed independently. In practice, the elements and game mechanics are applied in a personalized manner and according to the objectives pursued [91]. On the Amazon website, the points reflect the usefulness of the comments, the badges show the prestige of the reviewer, and the ranking indicates the reviewer’s position with respect to others, so its implementation in a grouped way is logical. In addition, when analysing the PBLs, they presented high correlations, they could be grouped into a second-order construct, and it was found that they could be treated as a unit in subsequent works. In environments in which the system requires trust between two or more parties, and it cannot be explicitly guaranteed or cannot be managed, the reputation points system becomes a key element [60]. On the other hand, we can conclude with the fact that the gamification in itself does not generate a more socially responsible consumption. However, it could create space for responsible behavior by the consumers.

5.2. Implications

The impact of product reviews on sales has been widely studied by academia. However, limited attention has been paid to the antecedents. We believe that this research contributes to the conceptual and empirical understanding of reviewer profiles and their characteristics. This study contributes to existing reviews of e-commerce and gamification research in several ways. It has been confirmed that we can characterize online product reviewers based on their intrinsic motivations. Specifically, the intrinsic motivations that mainly serve to identify types of millennial commentators are egoistic motives, competence and social relatedness, with egoistic motives being the main discriminator. However, although the intrinsic motivation of autonomy does not serve to determine the type of reviewer, we cannot forget its importance in terms of self-satisfaction [44].

Intrinsic motivations, in turn, can be associated with extrinsic motivations, such as gamification, in groups of individuals with similar characteristics. In fact, the three groups of reviewers analysed (CS, CC and II) are correctly sorted into two groups with well-differentiated characteristics (those who like game elements and those who do not). Using extrinsic rewards, such as gamification offers, we can connect with the intrinsic motivations of individuals. In fact, the points affect the status of the user and their reputation. For those reviewers seeking recognition, earning points continually will foster their continued engagement with the platform. Obtaining badges helps reviewers to satisfy their intrinsic desire for recognition before the rest, and the badge obtained allows them to be identified and stand out from others. Rankings serve as personal achievement and allow prominence for some reviewers (CS and CC); for others, they create a fun environment and reflect quality and integrity. In contrast, for reviewer II, the leaderboards will normally have no value or utility. In this sense and in a general way, we can say that CS and CC reviewers will positively accept gamification elements. In summary, we can conclude that the extrinsic motivations provided by gamification are associated with profiles that are intrinsically selfish. In particular, it seems that reviewers’ motivations are egocentric in nature and primarily based on the hedonic desire to gain a reputation and social recognition or to draw attention.

Gamification elements should be targeted at specific profiles, rather than implementing them generically. PBLs can be used generically due to their internal consistency, but results will be obtained if the reviewers are not segmented. We have been able to observe that two groups of individuals appear with clear attitudes (positive or negative) towards gamification. Targeting gamification at individuals who reject it does not make any sense since it would incur unnecessary costs of time, money, and monitoring and could even have adverse effects. To optimize resources, e-commerce companies should propose specific marketing strategies. For those individuals with high selfish motivations, the gamification application has a high probability of working. It is therefore important to detect egocentric profiles as soon as possible to guide gamification towards them. Actions such as offering different landing pages depending on the type of user (pro-gamification versus anti-gamification) would favour the success of gamification. Furthermore, if the interface is easy to use and shows what attracts the individual the most, it will result in their engagement, generating more participation and activity [64,92].

The elements of gamification, such as the points obtained, medals and positions in the ranking, should always be visible for individuals who show a positive attitude and be in the background for those who are reluctant to accept them. Using tutorials or guided videos can help in this regard. Additionally, new additional gamification elements, such as progress bars, can be used to show progress in terms of competence or degree of fulfilment of certain challenges of the reviewers. For those reviewers driven by selfish motives, more striking badges can be used, and highlighting more their positions in the ranking could satisfy their desire to attract attention.

In contrast, care must be taken because, if gamification is implemented in a generic way in individuals with low selfishness and who have a negative attitude, it can create demotivation or fatigue. Other possible approaches to gamification to attempt to influence individuals who are not motivated by selfishness would be through social relatedness or altruism. Applying game mechanics and components that benefit the community could motivate these reviewers.

Regarding the models used for classification, the good results obtained in terms of accuracy support their use in subsequent studies. In this sense, the J48 (C4.5) algorithm is presented as a very good tool to classify the reviewers of products of e-commerce pages, endorsing the good classification of a new reviewer with high reliability. This algorithm presents user-friendly results that can be easily interpreted by the community, and it has allowed the model to be pruned. It was possible to classify the first problem with only three attributes and the second problem with only one attribute. Furthermore, its use also made it possible to detect subcategories within one of the individual profiles (e.g., CC). Another advantage that the use of decision trees has offered us has been in detecting the values based on which individuals can be categorized according to their characteristics.

All the previous considerations generate implications of interest both for the design of educational policies that promote the SRC as well as business management through gamification. For the companies, the knowledge generated could be useful as it expands the possibilities to line up with the ethical concern of the consumer and promote sustainable engagement. Further, gamification allow to adapt the marketing strategies, both for companies that decide to tend to socially responsible consumers, and for institutions that aim to promote more responsible consumption. This is something rather important for making it easier to design strategies better adapted to their target, from institutions or from other companies that consider this market segmentation. We cannot hide that the purpose of this investigation emerges from personal concern for all the consequences and the limits of consumption. The vast literature regarding this is proof that is not about an irrational or poorly stated uneasiness, which means it is subject for debates and critics. Today, however, very few deny the important economic, social and environmental effects that are closely linked to the phenomena of consumption and the new digital era, such as the gamification phenomenon.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The sample size was relatively small, although it was representative of the Spanish reviewers. Future research should include a more diverse sample of reviewers of different age generations (Generation X or Generation Z), for example, to study possible differences and cross-cultural factors. A larger sample size could also bring more statistical power for analysis, and including qualitative questions in the survey could allow for a better interpretation of the results.

RPS systems reflect the reputations of users and the recognition of other users, but it is essential that the mechanisms for obtaining them be clear. Amazon uses its own algorithm to determine the positions in the rankings of reviewers. Although the reviewers trust its fairness, perhaps they should offer more transparency when calculating it, in favour of greater motivation of users based on knowing the rules of the game better.

Individuals with high egocentricity, along with a positive attitude towards gamification, might come to comment compulsively, and the quality of the comments could be diminished. It would be interesting to study in future lines of research the extent to which gamification becomes the end and not the means to promote online product reviews.

In this study, we assessed participants’ perceived competence and relatedness, that are included in the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory Scale [44]. In future works, the authors of this study will consider the use of a complete Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) framework for ensuring the analytical validity in more traditional terms. This is a multidimensional measurement grounded in the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) used in assessing the subjective experiences of participants.

The relationship of the reviewers’ profiles with other constructs would be very useful to future work. For example, in the case of egoism, in addition to the reasons for the need for self-enhancement, reciprocity could be considered a benefit for individuals to engage in social exchange [93,94]. Millennials are also prone to reaching flow states while making comments or browsing e-commerce pages. It has been shown that the state of flow, together with extrinsic motivations, such as gamification, in millennial users generates positive effects on their behavioral intentions [42]. Finally, since the use of e-commerce systems based on eWOM pursues brand loyalty and trust [95,96,97], we propose their future observation. Despite the studies on social sustainability and gamification progressively acquiring greater relevance within the literature on consumer behavior, we are still facing a topic that needs to be better understood. More research and new evidence on these aspects are necessary for the design of policies that effectively promote a more committed consumption. It is not only important to create conscience but also assist the means to materialize it. This precisely constitutes one of the concerns in Social Marketing, an area that could be key to work on all these matters. Hence, the study of gamification and sustainability would appear to us as an object of investigation that is socially urgent and relevant. We hope that with this investigation we add at least a little more knowledge to advance the understanding of a complex reality to be apprehended and promoted. However, that is in addition to what, with more or less success, we have attempted to respond to in these lines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; methodology, J.J.P.-B.; software, J.J.P.-B.; validation, A.G.-J.; formal analysis, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; investigation, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; resources, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; data curation, J.J.P.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; writing—review and editing, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; visualization, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; supervision, A.G.-J., J.J.P.-B. and F.F.-N.; project administration, A.G.-J. and J.J.P.-B.; funding acquisition, A.G.-J. and J.J.P-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research work of F.F.N. is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science under ProjectENE2017-88889-C2-1-R.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Constructs, Elements, Measures and Sources.

Table A1.

Constructs, Elements, Measures and Sources.

| Construct | Element | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic Motivation | Autonomy | I have complete freedom to decide the way I review products |

| I don’t feel pressured when I comment on products | ||

| I feel free to express my opinions when reviewing. | ||

| Competence | Improving my reviewing skills is very important to me. | |

| I think that I have developed my competence by reviewing products | ||

| Reviewing helps me to develop my skills (reading and comprehension) | ||

| Social Relatedness | I like to contact with people when posting reviews. | |

| I find it gratifying to be able to interact with people in Amazon community | ||

| I enjoy interacting with people from Amazon | ||

| Reis et al., 2000; Ryan and Deci, 2000. | ||

| Egoistic Motivation | I need to be recognized by others | |

| My reputation is very important to me | ||

| I like to attract people’s attention | ||

| Self-developed. | ||

| Altruistic motivation | Helping others make informed buying decisions is important to me | |

| I review because I want to be helpful to other people. | ||

| I feel good when I help the community | ||

| Clary et al., 1998; Mathwick and Mosteller, 2017. | ||

| Gamification | Points | Receiving votes for considering my comments helpful rewards my efforts |

| The points/votes system correctly reflects my efforts to comment on products | ||

| I like to receive points/votes when commenting on products | ||

| Badges | The badges that can be obtained from Amazon (for example: Top Reviewer 1000) | |

| reflect the good work done as a reviewer | ||

| I like badges and I seek them | ||

| My efforts to comment on products are perfectly reflected with the badges | ||

| Leaderboards | Improving my ranking in the reviewer system is important to me | |

| The reputation that I have as a reviewer can be easily checked in the ranking | ||

| The ranking of Top Reviewers reflects my status when I comment | ||

| I think that it is important to know the percentage in which users consider | ||

| my comments helpful, so that I can compare with others | ||

| Werbach and Hunter, 2012. Self-developed. | ||

References

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D. Digital Sustainability and Entrepreneurship: How Digital Innovations Are Helping Tackle Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregori, P.; Holzmann, P. Digital sustainable entrepreneurship: A business model perspective on embedding digital technologies for social and environmental value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, A.; Karrbom-Gustavsson, T.; Dobers, P. Transition towards and of sustainability—Understanding sustainability as performative. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, G.; González Fernández, C.; Uruburu Colsa, A. Unleashing the convergence amid digitalization and sustainability towards pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A holistic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 122204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jurado, A.; Pérez-Barea, J.J.; Nova, R.J. A New Approach to Social Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J. Predicting the helpfulness of online customer reviews across different product types. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Gwinner, K.P.; Swanson, S.R. What makes mavens tick: Exploring the motives of market mavens’, initiation of information diffusion. J. Consum. Mark. 2004, 21, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Mosteller, J. Online reviewer engagement: A typology based on reviewer motivations. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Barea, J.J.; Montero-Simó, M.J.; Araque-Padilla, R. Measurement of socially responsible consumption: Lecompte’s scale Spanish version validation. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit. Mark. 2015, 12, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempert, P. Caught in the web. Progress. Groc. 2006, 85, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, C.; Precourt, G. Always on: Advertising, Marketing, and Media in an Era of Consumer Control; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Karahanna, E.; Watson, R.T. Unveiling usergenerated content: Designing websites to best present customer reviews. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Online Consumer Reviews, European Parliamentary Research Service. Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/online-consumer-reviews---the-case-of-misleading-or-fake-reviews.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. The impact of social media on lodging performance. Cornell Hosp. Rep. 2012, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Handbook of Self-Determination Research; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments 2021, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J. Transforming homo economicus into homo ludens: A field exper-iment on gamification in a utilitarian peer-to-peer trading service. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2013, 12, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J. Do badges increase user activity? A field experiment on effectsof gamification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 71, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlutter, R.; Capella, M.L. The gamification of advertising: Analysis andresearch directions of in-game advertising, advergames, and advertising in socialnetwork games. J. Advert. 2013, 42, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonde, M.T.; Makransky, G.; Wandall, J.; Larsen, M.; Morsing, M.; Jarmer, H.; Sommer, M.O.A. Improving biotech education through gamified laboratory simulations. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, K.R.; Fox, J. Leaderboards in a virtual classroom: A test of stereo-type threat and social comparison explanations for women’s math performance. Comput. Educ. 2014, 78, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.A.; Madden, G.J.; Wengreen, H.J. The FIT game: Preliminary evalu-ation of a gamification approach to increasing fruit and vegetable consumptionin school. Prev. Med. 2014, 68, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lounis, S.; Pramatari, K.; Theotokis, A. Gamification is all about fun: Therole of incentive type and community collaboration. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2014, Tel Aviv, Israel, 9–11 June 2014; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Spanellis, A.; Harviainen, J.T. Transforming Society and Organizations through Gamification: From the Sustainable Development Goals to Inclusive Workplaces; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Tuunanen, J. Player Types: A Meta-synthesis. Trans. Digit. Games Res. Assoc. 2014, 1, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A. Gen Y customer loyalty in online shopping: An integrated model of trust, user experience and branding. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ortega, B. Don’t believe strangers: Online consumer reviews and the role of social psychological distance. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, F.; Liu, H. Search product and experience product online reviews: An eye-tracking study on consumers’ review search behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Barea, J.J.; Espantaleón-Pérez, R.; Šedík, P. Evaluating the Perception of Socially Responsible Consumers: The Case of Products Derived from Organic Beef. Sustainability 2020, 12, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón, C.; Valverde, B.R.; Simó, M.J.M.; Padilla, R.Á.A.; Barea, J.J.P. Valoración por el consumidor de las características hedónicas, nutritivas y saludables del amaranto. Entreciencias 2018, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Barea, J.J. Consumidor Responsable ¿Globalizado? Editorial Académica Española: Saarbrücken, Alemania, 2018; ISBN 13: 978-620-2-11260-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Barea, J.; Fernández-Navarro, F.; Montero-Simó, M.J.; Araque-Padilla, R. A socially responsible consumption index based on non-linear dimensionality reduction and global sensitivity analysis. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 69, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Porcentaje de las Compras Online Realizadas por Millennials por País Europa 2019. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1009558/porcentaje-de-las-compras-online-realizadas-por-millennials-por-pais-en-europa/ (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- Medallia Institute. Millennials: Your Most Powerful Brand Advocates. Available online: http://go.medallia.com/rs/669-VLQ-276/images/Medallia-Millennials-Your-Most-Powerful-Brand.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Clark, R.A.; Goldsmith, E.B. Extending the psychological profile of market mavenism. J. Consum. Behav. 2006, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Wiertz, C.; De Ruyter, K. Social capital production in a virtual P3 community. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 34, 832–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Alexander, M. The Role of Customer Engagement Behavior in Value Co-Creation: A Service System Perspective. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Herrmann, A. The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. Intrinsic Motivation; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R.; Williams, G. Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of Learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 1996, 8, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, S.; Przybylski, A. Virtual worlds and the learner hero: How today’s video games can inform tomorrow’s digital learning environments. Theory Res. Educ. 2009, 7, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Witte, H.; Soenens, B.; Lens, W. Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the Work-related Basic Need Satisfaction scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, S.; Ryan, R.M. Glued to Games: How VIDEO games Draw Us in and Hold Us Spellbound; Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.K.J.; Khoo, A.; Liu, W.C.; Divaharan, S. Passion and intrinsic motivation in digital gaming. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Gunz, A. Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. J. Personal. 2009, 77, 1467–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.; Rigby, C.; Ryan, R. A motivational model of video game engagement. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What Drives Consumers to Spread Electronic Word-of-Mouth in Online Consumer-opinion Platforms. Decis. Support. Syst. 2012, 53, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendapudi, N.; Singh, S.N.; Bendapudi, V. Enhancing helping behavior: An integrative framework for promotion planning. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Altruism and economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R.V. E-Tribalized Marketing? The Strategic Implications of Virtual Communities on Consumption. Eur. Manag. J. 1999, 17, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.K. Octalysis: Complete Gamification Framework; Gamification: Birmingham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. Game mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics. Libr. Technol. Rep. 2015, 51, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Werbach, K.; Hunter, D. For the Win: How Game Thinking can Revolutionalize Your Business; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Schultz, M.; Corley, K.G. Organizational identity, image, and adaptive instability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheskin Research. Trust in the Wired Americas. Available online: http://saywhatcr.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/trust.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2020).

- Otterbacher, J. ‘Helpfulness’ in online communities: Ameasure ofmessage quality. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 4–9 April 2009; pp. 955–964. [Google Scholar]

- Razavi, Y.; Ho, B.; Fox, M.S. Gamifying E-Commerce: Gaming and social-networking induced loyalty, The European Business Review. Available online: https://www.europeanbusinessreview.com/gamifying-e-commerce-gaming-and-social-networking-induced-loyalty/ (accessed on 15 March 2020).

- Labrecque, L.I.; vor dem Esche, J.; Mathwick, C.; Novak, T.P.; Hofacker, C. Consumer power: Evolution in the digital age. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. A definition for gamification: Anchoring gamification in the service marketing literature. Electron. Mark. 2017, 27, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Hamari, J. Does gamification satisfy needs? A study on the relationship between gamification features and intrinsic need satisfaction. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 46, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellar, M.; Watters, C.; Duffy, J. Motivational factors in game play in two user groups. In Proceedings of the DiGRA 2005 Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–20 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.; Gardner, J. Personality, motivation and video games. In Proceedings of the 22nd Conference of the Computer-Human Interaction Special Interest Group of Australia on Computer-Human Interaction—OZCHI ’10, New York, NY, USA, 22–26 November 2010; pp. 276–279. [Google Scholar]

- Zammitto, V.L. Gamers’ Personality and Their Gaming Preferences. Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, J.L.; Lucas, K.; Greenberg, B.S.; Lachlan, K. Video game uses and gratifications as predictors of use and game preference. In Playing Videogame: Motives, Responses, and Consequences; Vorderer, P., Bryant, J., Eds.; LEA: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, H.T.; Sheldon, K.M.; Gable, S.L.; Roscoe, J.; Ryan, R.M. Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, E.G.; Snyder, M.; Ridge, R.D.; Copeland, J.; Stukas, A.A.; Haugen, J.; Miene, P. Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresfelean, V.P. Analysis and predictions on students’ behavior using decision trees in Weka environment, Information Technology Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2007 29th International Conference on Information Technology Interfaces, Cavtat, Croatia, 25–28 June 2007; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision tres. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Comparison of decision tree methods for finding active objects. Adv. Space Res. 2008, 41, 1955–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, I.H.; Frank, E.; Hall, M.A. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal, G.; Garg, D.K. Comparison of various clustering algorithms. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2014, 5, 3074–3076. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, J.P.; Perreault, W.D., Jr. Buyer–seller relationships in business markets. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Erson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; William, C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Eun, S.L. Exploring the usefulness of a decision tree in predicting people’s locations. Procedia Soc. Behavioral Sci. 2014, 140, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. ROC graphs: Notes and practical considerations for researchers. Mach. Learn. 2004, 1, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, I.; Hall, M.; Holmes, G.; Pfahringer, B.; Reutemann, P. The WEKA data mining software: An update. ACM Sigkdd. Explor. Newsl. 2009, 11, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, E.; Wang, X.; Jambari, N.N.; Rhyner, C.; Olzhausen, J.; Pérez-Barea, J.J.; Figueredo, G.P.; Alcocer, M.J.C. Novel in vitro diagnosis of equine allergies using a protein array and mathematical modelling approach: A proof of concept using insect bite hypersensitivity. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2015, 167, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, J.; Bui, D.T.; Yunus, A.P.; Jia, K.; Song, X.; Revhaug, I.; Zhu, Z. Optimization of causative factors for landslide susceptibility evaluation using remote sensing and GIS data in parts of Niigata, Japan. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantardzic, M. Data Mining: Concepts, Models, Methods, and Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Constant, D.; Kiesler, S.; Sproull, L. What’s mine is ours, or is it? A study of attitudes about information sharing. Inf. Syst. Res. 1994, 5, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufie, M.G.E.; Kesa, H. Millennials motivation for sharing restaurant dining experiences on social media. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Magno, F.; Cassia, F.; Bonfanti, A.; Vigolo, V. The Effects of Altruistic and Egoistic Motivations on Online Reviews Writing Frequency. In Proceedings of the Excellence in Services International Conference, Paris, France, 30–31 August 2018; pp. 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Bunchball. Gamification 101. An Introduction to the Use of Game Dynamics to Influence Behavior. Available online: http://www.bunchball.com/sites/default/files/downloads/gamification101.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2019).

- Liu, X.; Wei, K.K. An empirical study of product differences in consumers’ E- commerce adoption behaviour. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2003, 2, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, M.M.; Faraj, S. It is what one does: Why people participate and help others in electronic communities of practice. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2000, 9, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jurado, A.; Castro-González, P.; Torres-Jiménez, M.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. Evaluating the role of gamification and flow in e-consumers: Millennials versus generation X. Kybernetes 2019, 486, 1278–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingar, P.; Kumar, H.; Sharma, T. Enterprise E-Commerce; Meghan-Kiffer Press: Tampa, Finland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam, G. Building stronger brands through online communities. Mit. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2008, 41, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).