Abstract

Sustainability-oriented start-ups are fundamental to developing solutions for, and to fostering, a societal transition towards a low carbon society. In this context, social impact accelerators (SIAs) are organizations specializing in accelerating the progress of sustainability-oriented start-ups. In order to design their accelerator elements (e.g., training, coaching, and funding) effectively, SIAs must be aware of the knowledge needs of start-ups to support them in developing a sustainable business model (SBM). Using a case study approach, we present one of the largest cleantech accelerator programs in Europe, the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator. Based on the program’s curriculum and manual in 2019, we analyze from the perspective of the program how cleantech start-ups could be supported in the development of their SBMs by presenting accelerator elements that are intended to support start-ups in reducing their knowledge needs by (1) providing new knowledge to start-ups (e.g., trainings, workshops, and e-learning), (2) supporting start-ups’ assimilation of new knowledge (e.g., coaching), and (3) supporting start-ups’ application of new knowledge (e.g., documentation of planning and reporting as part of the program’s contract design). Further, we discuss the knowledge needs of 63 European start-ups before and their progress as a result of accelerator participation in developing a SBM based on qualitative and quantitative data. All 63 start-ups participated in the same batch of the accelerator in 2019. Regarding the development of a SBM, knowledge needs are described considering the triple bottom line including the economic, ecological, and social layer of a business model. Based on the start-ups’ evaluation, we reflect—with a focus on the environmental layer—about the most promising content and support elements of our SIA case to address the different layers, discuss their combination, and present improvement potentials to reduce start-ups’ knowledge needs. With our findings, we claim to contribute to theory development in the emerging literature on SIAs and give practitioners working with sustainability-oriented start-ups insights into the usefulness of start-up support programs and different accelerator elements for developing a SBM.

Keywords:

entrepreneurship; start-up; start-up support; accelerator; social impact accelerators; program design; Europe; EIT Climate-KIC; Regional Innovation Scheme; triple layered business model; sustainable business model; sustainable business modelling; sustainable business model development; sustainable business model innovation 1. Introduction

The development of sustainable business models (SBMs) is currently a main focus in academic literature, but also of high interest to business practitioners and policy makers [1]. By fostering SBMs, these actors intend to reduce the negative ecological and social impact of production and consumption systems, as well as to address societal challenges such as climate change [1]. Patzelt and Shepherd highlight that sustainable development opportunities are more difficult to recognize than those that are motivated merely by economic objectives [2]. Therefore, it seems that entrepreneurs who pursue the development of sustainable solutions require specific entrepreneurial knowledge to discover these opportunities [2]. Through the development of sustainability-oriented innovations and their corresponding SBMs considering the triple bottom line (profit, planet, and people), sustainable entrepreneurship can play a crucial role for the transition towards a low carbon economy [3,4].

Indeed, the development of SBMs is a complex process that requires specific support from the entrepreneurial ecosystem [5]. In entrepreneurial ecosystems, intermediaries, which are organizations that serve as an agent or broker in the innovation process, can support sustainable entrepreneurs through various generic and customized activities such as (i) forecasting and road mapping, (ii) information gathering and dissemination, (iii) fostering networking and partnerships, (iv) prototyping and piloting, (v) technical consulting, (vi) resource mobilization, (vii) commercialization, and (viii) branding and legitimation [6].

In the entrepreneurial ecosystem, start-up accelerator programs (hereafter we refer to them merely as accelerators) are relevant stakeholders that can serve as intermediaries [7,8]. They are a type of business incubation program, which attracts and supports start-ups in their development, while providing access to resources, knowledge, and important stakeholders [9].

Currently, little is known about how ecosystem stakeholders such as accelerators can specifically promote and contribute to sustainable entrepreneurship [8]. In this context, social impact accelerators (SIAs) are a relatively new phenomenon, since research has instead focused on traditional accelerators that are for-profit and target high-growth start-ups in technology sectors [10]. Therefore, research on SIAs is still young [10], and little is known on their intermediary role and how they support start-ups in developing a SBM. Hallen et al. state that research is still missing on the efficacy of accelerators, although they have become prominent stakeholders in entrepreneurial ecosystems [11].

Therefore, our overall goal is to improve the understanding of how an accelerator could support start-ups in developing a triple layered SBM by investigating the following two research questions in this study:

- Research question 1:What role can accelerators play in supporting start-ups to overcome their knowledge needs regarding the development of a triple layered SBM considering the triple bottom line (profit, planet, and people)?

- Research question 2:What knowledge do start-ups need concerning the development of a triple layered SBM?

To answer this research questions, we present and discuss, with a case study approach, the EIT Climate-KIC RIS accelerator and its elements as an example of a SIA to investigate how a SIA can support start-ups in developing a triple layered SBM. The design elements of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator are described based on official internal program documents (manual and curriculum of the program from 2019). Further, we examine the knowledge needs of 63 European start-ups regarding their development of a triple layered SBM, which participated in the same batch of this accelerator in 2019. In doing so, we investigated the start-ups’ knowledge needs at the beginning of the program and their progress in developing a SBM as a result of accelerator participation at the end of the program with quantitative ratings and qualitative data.

With this study, we intend to enhance the understanding of how a SIA can support start-ups in developing a triple layered SBM. For researchers, our findings may serve as an input for the further operationalization of knowledge needs for developing a SBM, which could be used in future studies as well as a steppingstone for assessing the efficacy of accelerator design elements. For practitioners designing and running SIAs, we provide valuable insights for reflecting on their curricula, and the efficacy of individual and combined accelerator elements for supporting start-ups in developing SBMs.

This study is structured as follows. The subsequent section presents SIAs as intermediaries for supporting start-ups in developing a SBM. The third section introduces the three layers of a SBM considering the triple bottom line (economic, ecological, and social layers) and presents the necessary knowledge for each layer. The fourth section describes the research design of this study. The fifth section presents the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator and its design elements for supporting start-ups in developing a SBM as a SIA case study. In the sixth section, the findings regarding the accelerator’s efficacy in supporting start-ups in their development of a SBM and improvement potentials for the program from the start-ups’ perspective are discussed. The seventh section provides implications for theory and future research and outlines practical implications, for those who fund, setup, operate, and manage SIAs, on how they can appropriately support start-ups in developing a SBM. The study closes with a brief conclusion.

2. Social Impact Accelerators

Companies require specific support for the application of sustainability-related knowledge [12]. Therefore, intermediaries that provide specific support services for the design and development of sustainable solutions have emerged [12]. In particular, these intermediaries support companies by providing guidance in the social impact and sustainability assessment of their solutions with qualitative and quantitative methods (e.g., cradle-to-cradle, life cycle assessment, and carbon footprint analysis) [12].

Accelerators are relevant intermediaries of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, which can provide relevant expertise and knowledge to start-ups through formal and informal education (e.g., through seminar-, cohort-, contact-, or mentor-based learning) [7]. In general, accelerators are “a fixed-term, cohort-based program for startups, including mentorship and/or educational components, that culminates in a graduation event” [13] (p. 1782).

In recent years, a new accelerator form for supporting start-ups has emerged: the social impact accelerator (SIA) [10]. SIAs can help start-ups to overcome their perceived resource constraints and needs (e.g., physical, financial, and social capital, knowledge, and legitimacy) [14], while creating a social and environmental impact in addition to financial returns [10]. SIAs help start-ups to overcome legitimacy needs by being affiliated with an accelerator and building a brand to raise necessary money [10]. Moreover, Yang et al. emphasize that start-ups often seek help from SIAs to develop and refine their SBM [10].

3. The Relevance of Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Necessary Knowledge for Developing a Triple Layered SBM

Sustainable entrepreneurship is considered to be a major contributor for the development of sustainable products and processes [15]. In this context, Patzelt and Shepherd define sustainable entrepreneurship as “the discovery, creation, and exploitation of opportunities to create future goods and services that sustain the natural and/or communal environment and provide development gain for others” [2] (p. 632). In this study, we follow Demirel et al., who use the terms “eco,” “environmental,” “green,” and “sustainable” interchangeably and refer to businesses that pursue activities to reduce negative environmental impacts (e.g., often through traditional pollution clean-up, energy and resource efficiency, or solutions that reduce carbon emissions and environmental degradation) [4].

Start-ups that develop sustainable solutions require a viable business model to scale up and to create an impact at a large scale [3]. SBMs should follow a triple bottom line approach by considering a wide range of stakeholders, and thus should take three different layers into account: (1) economic (profit), (2) environmental (planet), and (3) social (people) layers [3,16,17,18]. Joyce and Paquin highlight that the development of SBMs is a complex process and requires the horizontal and vertical coherence on and across all three different layers [18].

Moreover, businesses should measure their economic, environmental, and social impact [3,16]. For instance, customers could require appropriate information regarding the environmental and social impact of products and services to make informed buying decisions, while businesses can also obtain labels that could increase customers’ awareness [17].

In the following, relevant knowledge aspects of each layer are presented.

3.1. Economic Layer: Knowledge about Market, Law, Legislation and Economic Objectives

The economic layer of a SBM concerns the economic objectives and value capture of the business [17]. This refers to knowledge about how to earn revenues and to ensure an economic sustainability of business activities (business planning, cost structure, and revenue model), while also providing a social and environmental value [3]. For market acceptance of sustainable innovations, de Medeiros et al. identified market, law, and legislation knowledge as a critical success factor [19]. Basically, this knowledge comprises the fulfillment of customers’ and society’s expectations, the drivers for the demand of sustainable solutions, market intelligence, as well as competitor monitoring, and the knowledge about relevant environmental legislation and regulation, including financial support from governments for sustainable innovations [19].

3.2. Ecological Layer: Knowledge about Ecological Indicators and Objectives

The ecological layer of the SBM refers to the ecological objectives of the business [17]. Thus, knowledge about the ecological objectives and suitable indicators to measure them are necessary for decision-making, since they “reflect the need to manage the ecological impacts of the consumption and production of a product or service through all phases of the physical product life cycle” [17] (p. 130). According to Belz and Peattie [17], ecological objectives include

- Material use (e.g., the use of non-renewable and renewable energies and the use of toxic materials);

- Water use (e.g., volumes used during production and/or product use);

- Emissions (e.g., greenhouse gas, toxic, and ozone-depleting emissions);

- Effluents (e.g., the effect on the water quality of production and/or use);

- Waste (e.g., no ability to reclaim and toxic materials/compounds).

For the complementation of economic indicators, Volkmann et al. propose that new metrics for the measurement of sustainable impact are necessary, e.g., in terms of reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) [8]. In this context, boundary setting by considering in which areas a business is active and how far its impact can and should reach is very important for measuring its ecological impact [1].

3.3. Social Layer: Knowledge about Social Objectives

The social layer is the last layer of a SBM and concerns the social objectives of the business [17]. At the international level, the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) have been accepted to secure peace and prosperity for people and the planet by ending poverty, improving health and education, reducing inequality, and fostering economic growth, all while fighting climate change and preserving oceans and forests [20]. Volkmann et al. argue that the explicit linkage of business activities to the UN SDGs and the measurement of entrepreneurial impact in achieving environmental and societal goals can be considered as the most recent contextualization of entrepreneurship and sustainability [8].

4. Research Design

Thus far, the most existing research has focused on rather “traditional” for-profit accelerators, and very little research has been conducted on SIAs in spite of their increasingly important role for supporting social entrepreneurs [10]. We use a case study approach for examining how a SIA can support start-ups in providing necessary knowledge for developing a triple layered SBM.

For instance, Bank et al. used a case study approach to analyze how a sustainability-oriented incubator selects and recruits tenants, since few research studies have focused on sustainable incubators so far [21]. In general, accelerators seem to extend existing business incubation types such as incubators and are distinct in their design [22].

A case study approach is especially suitable for exploratory research like our study [23]. We consider the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator as a promising research setting for investigating our research questions, which could also reveal valuable insights for future research topics. By researching a case such as the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator, it is possible to create a greater level of consciousness about the role of SIAs in supporting start-ups in their development of a SBM even from a single case study, when cases provide unique access [23,24].

For data collection and analysis, we had unique access to official internal program documents and the start-ups of the accelerator that participated in the same batch in 2019, since the Center for Industry and Sustainability co-developed and implemented the program in 2016 and both authors work at the Center for Industry and Sustainability. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the used data sources of this study.

Table 1.

Data sources describing the services and support of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator in 2019.

Table 2.

Data sources concerning start-ups’ knowledge needs at the beginning of the program and their progress as a result of accelerator participation in developing a SBM in 2019 (hereafter referred to as the accelerator 2019 in the quantitate ratings).

The case description of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator as a SIA example in the next section is based on official internal program documents (the accelerator manual and curriculum from 2019). The role of the funding entity (EIT Climate-KIC), the steering organization of the accelerator (Center for Industry and Sustainability), and the local program delivery partners (RIS partners and their local coaches), as well as their responsibilities in supporting the participating start-ups, are described. In addition, one author of this study co-developed the concept and implemented the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator in 2016, and thus has broad experience and insights into this case. Further, both authors co-developed the on-boarding and evaluation questionnaire for data collection, as well as learning material and exercises for the start-ups, in which the start-ups must reflect on the three layers of their SBM. This personal involvement in the program ensures an in-depth understanding of the intended design and functioning of the EIT Climate KIC RIS accelerator. However, the authors describe the program only based on official internal program documents to reduce potential bias in assessing the efficacy of different accelerator elements and to avoid personal interpretations of the results. Further, a critical reflection on the program and the accelerator elements comes from the perspective of the participating start-ups, while the perspective of the local RIS partners in the different countries is not included in the analysis.

This study is to our knowledge the first analysis of how SIAs can support start-ups in developing a SBM and measuring start-ups’ knowledge needs before and their progress as a result of accelerator participation. Since we did not find any tested items in literature regarding our research questions, items concerning the start-ups’ knowledge needs were developed based on literature dealing with SBMs (e.g., [3,16,17]), necessary market, law, and legislation knowledge for developing sustainable solutions [19], and start-ups’ general perceived resource and knowledge needs [14]. The items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to seven (strongly agree). Earlier versions of these items were used in the program in 2018 to ensure their comprehensibility, and to test their relevance for start-ups’ practice in order to align the accelerator’s program and to provide appropriate support elements (e.g., learning material, coaching, and workshops at the international boot camp of the program).

For data collection concerning the start-ups’ knowledge needs and to assess the efficacy of the program, one team member of each start-up received a personalized link via e-mail to an online questionnaire and was asked to rate and qualitatively indicate the start-up’s knowledge needs at the beginning of the program for developing a SBM (“on boarding”). At the end of the program (“evaluation”), the same participant received the personalized link via e-mail again. The person was asked to rate the start-ups’ progress in developing a SBM as a result of accelerator participation, and to assess the overall program as well as to indicate qualitatively the perceived efficacy of different accelerator elements for developing a SBM. To ensure confidentiality and to prevent socially desired answers, all data were gathered anonymously [25].

The respondent of each start-up was primarily the focal founder or a team member, who submitted the start-up’s application form to the accelerator. The link for the online questionnaire was sent via e-mail to all 83 start-ups that participated in the same batch in 2019. In total, 65 respondents filled in the online questionnaire at the beginning and end of the program. The online survey was only sent to program participants, so no key respondent check was necessary. After checking for unengaged responses, two cases were excluded, resulting in 63 useable cases for this study. This led to a response rate of 75.9% calculated in relation to the number of all 83 start-ups of the accelerator batch in 2019.

These 63 start-ups covered a broad variety of markets. Based on the measures of Armanios et al. [26], 73.0% of the start-ups were in an early development phase (R&D/planning and pre-revenue phase). According to Klewitz and Hansen [27], 74.6% developed a product or service innovation. Moreover, the primary offer was a physical product (42.9%), and the start-ups were mainly active in the B2B market (55.6%).

Moreover, 79.4% of the start-ups had already registered their business as a firm. The average age of these 50 start-ups was 17.4 months since their registration as a firm. This average firm age was almost the same as the firm age of a data sample of 1311 accelerator start-ups of Yu [28], with 17.0 months on average. Therefore, start-ups of this study may be comparable to start-ups of other accelerator programs and may have similar needs.

Finally, for 79.4% of the start-ups, it was their first-time participating in the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator, and 65.1% had not participated in any other accelerator before.

All descriptive data concerning the start-ups can be found in Appendix C.

5. The EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator Case

The following section presents the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator case. Appendix A summarizes the design of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator based on the accelerator design choices of Cohen et al. [13]. With this case description, we aim at presenting the functioning of a SIA example with its background, its design, the start-up selection process, and the accelerator elements that support start-ups in developing a SBM.

5.1. Background

Policy makers can steer the social and technological progress of regions and societies by specializing in strategies such as sustainability and funding incubation programs in these areas [29]. For instance, the European Commission supports the establishment of accelerators with a focus on specific technological domains or areas, which are part of its economic development program [22]. These accelerators are supported by the European Institute of Innovation & Technology (EIT), which has set up several Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) to address major societal challenges and changing environments [30]. The goal of the KICs is the creation of a favorable environment for innovation including start-ups that develop relevant solutions, and the acceleration of their development with funding and suitable training of entrepreneurs [30].

In this context, EIT Climate-KIC has the aim of developing solutions and services to mitigate and adapt to climate change for a decarbonized and sustainable economy [31,32]. EIT Climate-KIC introduced its own accelerator program with a focus on climate impacts to develop successful cleantech start-ups [32]. In general, the EIT Climate-KIC Accelerator has a focus on rather early-stage start-ups. The EIT Climate-KIC has also set up an own accelerator for several countries from the EIT Regional Innovation Scheme (RIS) [33]. According to the European Innovation Scoreboard, the EIT RIS countries are modest and moderate innovators, so entrepreneurship activities should boost their innovativeness while educating entrepreneurs and developing cleantech start-ups for mitigation and adaptation to climate change [33].

5.2. Design

The EIT Climate-KIC RIS accelerator was co-developed by the Center for Industry and Sustainability (conceptual lead), which belongs to the Provadis School of International Management and Technology AG (Provadis Hochschule), and EIT Climate-KIC. The accelerator was set up and run for the first time in 2016. In 2019, the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator was conducted with a total of 83 start-ups in 12 different European countries from the EIT RIS (Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia).

The EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator follows a joint collaborative approach for the implementation and execution of the program. One central steering organization (Center for Industry and Sustainability) creates the framing documents for the program (e.g., curriculum, manual, and other guidelines), provides the funding for the participating start-ups, and is the contractual partner for the start-ups, while local partner organizations in each RIS country deliver the program according to the manual and curriculum. In doing so, local partner organizations are responsible for national promotion of the program, the recruitment of applicants, and the design of local program elements (e.g., selection of the right coaches, organization of workshops, training, and boot camps).

One central design element of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator is the mix between standardized and locally adapted activities. 80% of the activities are supposed to be standardized across all countries, and 20% of the activities are locally adapted to reflect and meet the local specifics of the regional ecosystem in each RIS country. The curriculum of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator was developed based on the lean start-up method developed by Ries [34] and has the aim to transform the start-ups’ ideas and solutions in marketable products and services.

The different accelerator elements can be distinguished whether they are organized locally by a local RIS partner or centrally either by the Center for Industry and Sustainability or by EIT Climate-KIC for all European locations (e.g., such as the EIT Climate-KIC Masterclasses). In addition, start-ups obtain access to the EIT Climate-KIC network to find potential customers or investors and have access to a large number of climate-related events.

In addition, the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator helps the participating RIS countries to strengthen their local start-up ecosystems, while also establishing a pan-European network among several countries and fostering cooperation among partner organizations and participating start-ups. This set-up has the aim to facilitate the exchange of knowledge, experiences, and contacts. In addition, this network can help start-ups to internationalize their activities and to access foreign markets.

5.3. Start-Up Selection Process

The EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator takes place once a year, and each batch has a duration of six months. The program has a competitive selection process, so all alumni start-ups of the program must re-apply for the next stage. Start-ups must hand in a written application. The final selection for the program takes place during a live pitch day.

In total, around 250 start-ups have participated in the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator since 2016. Most of them have previously participated in ideation formats and competitions from EIT Climate-KIC such as the Climathon or ClimateLaunchPad before they entered the accelerator in Stage 1 [35].

5.4. Accelerator Elements for Developing a Triple Layered SBM

After the final selection of all start-ups for the program, the contract for participation is set up (the contract between the start-up and Provadis Hochschule). In the contract, key milestones and deliverables that the start-ups must achieve during the program are defined. These key milestones represent the conditions/terms under which the funding is given. The key milestones and deliverables are discussed and defined in collaboration with local coaches.

For the achievement of key milestones, deliverables, and the development of a SBM, all start-ups receive education, which includes personal local coaching, local and international training, participation in local and international workshops as well as boot camps, and expert consultancy, funded by paid grants, on specific questions/issues according to their development stage.

According to Cohen and Levinthal [36], it is essential for firms to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it. Therefore, we clustered the accelerator elements of the accelerator curriculum (content) and manual (program delivery) into three different groups that fulfill different purposes to support start-ups in developing a SBM:

- (1)

- provide new knowledge to start-ups,

- (2)

- support start-ups’ assimilation of new knowledge, and

- (3)

- support start-ups’ application of new knowledge.

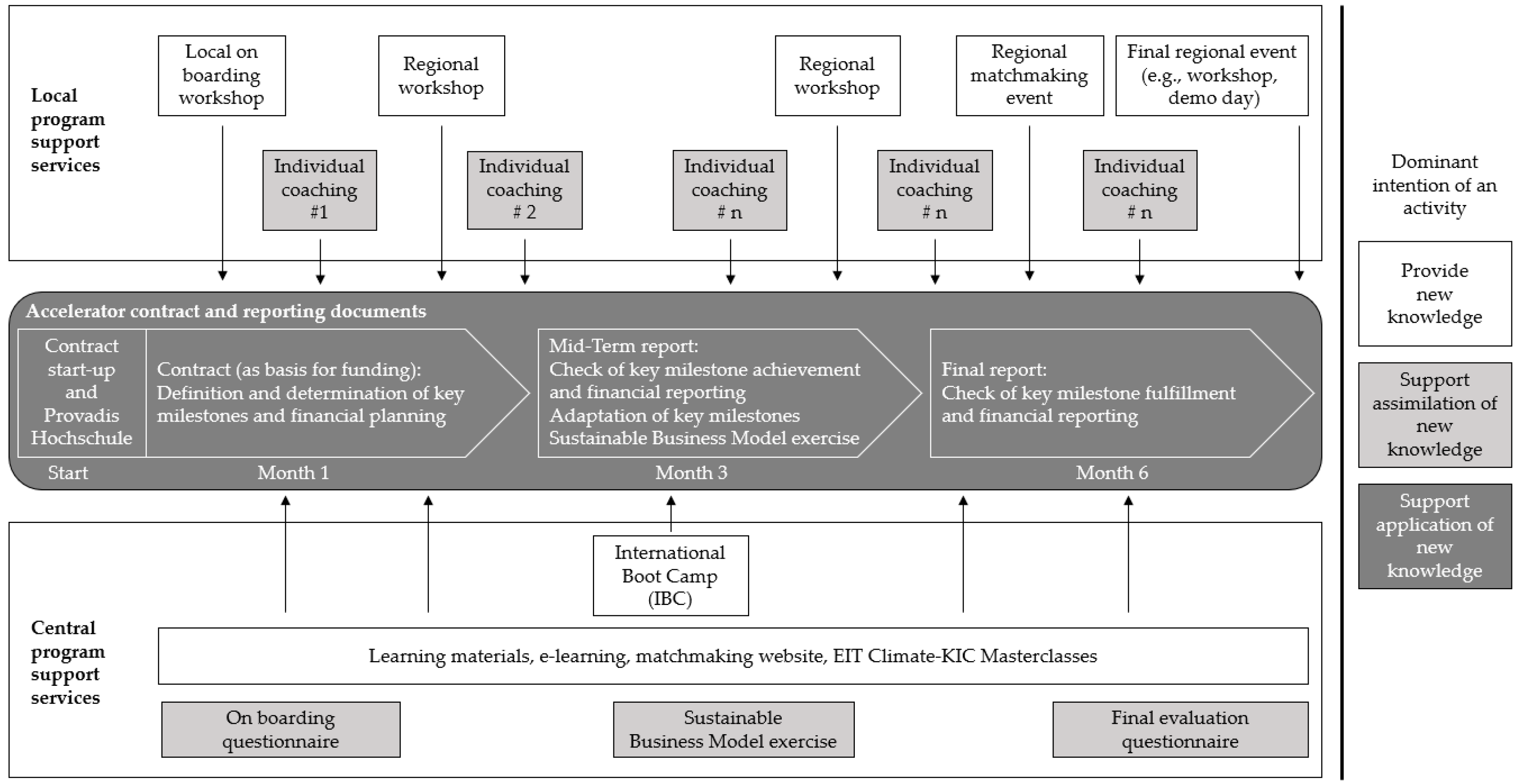

Appendix B gives an overview of all accelerator elements of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator, which are provided to the participating start-ups during the program, and how these elements should contribute to the start-ups’ development of a SBM. In the following, we briefly describe how the elements are intended to support the development of a SBM during the program, summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Accelerator elements of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator for supporting start-ups in developing a SBM. Note: Only compulsory elements of the program are depicted. Source: Own representation.

5.4.1. Provide New Knowledge to Start-Ups: Training, Workshops, and E-Learning

The concept of SBMs is available via optional e-learning material, which is centrally provided from the beginning of the program and is provided free of charge. During the international boot camp, at which all start-ups participated for two days in Frankfurt, knowledge is provided to make start-ups aware of the different layers of their business model, and to identify relevant interconnections between design choices on each and between the layers. Concerning the environmental layer, information on relevant tools for an environmental impact analysis is provided in different national and international training sessions and workshops during the program. Additional e-learning materials are provided on the EIT Climate-KIC learning platform including practical tools and heuristics to support start-ups in calculating their CO2 footprint.

5.4.2. Support Start-Ups’ Assimilation of New Knowledge: Coaching

The local coaches support the teams in their internal discussion and decision-making process. This coaching is locally organized and delivered by experienced coaches. The coaching starts with a face-to-face meeting, followed by either further face-to-face meetings or virtual meetings. The local coaches work with the start-ups on a regular basis during the whole program and support the development of a suitable business model, while also challenging it.

Concerning the ecological layer, the local coaches are asked to support start-ups in their eco-impact analysis, or if needed to connect start-ups with industry or methodological experts for CO2 foot printing. Before the start of the program, all local coaches receive introductory material for developing a SBM, which they can use on a voluntary basis during the coaching sessions. All coaches are trained by one central head coach in the concepts provided and are encouraged to apply multi-layer thinking concerning the start-ups’ business model in their coaching sessions. The central head coach check during the program with the local coaches whether they have any need for further clarification of these concepts.

5.4.3. Support Start-Ups’ Application of New Knowledge: Documentation of Planning and Reporting

The basis for the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator in 2019 was a contract between the Center for Industry and Sustainability (Provadis Hochschule) and each individual start-up. In this contract, each start-up describes its planned activities and defines key milestones with the planned financial expenditures for the funding, which they receive during the program.

With the mid-term report, the start-ups document their progress against the defined key milestones and report about the current financial spending so far. They have the opportunity to ask for a change of key milestones for the remaining part of the program. The economic layer of the business model is especially considered in the development and definition of the start-ups’ key milestones, which are part of the initial contract, the mid-term, and the final report.

With the mid-term report, all start-ups must hand in a SBM exercise, in which they self-assess their knowledge about the development of a SBM and specifically reflect on the integration of the ecological layer into their business model. Start-ups are also asked to discuss the results of this self-assessment with their local coach in order to adapt the ambition level and the necessary next steps during the program.

In general, the planning and reporting activities of the program including the contract, mid-term, and final report have direct financial implications for the start-ups and thus may represent a very effective instrument for supporting and guiding the start-ups’ development.

6. Findings

In the following, we present our findings on the efficacy of different elements of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator for supporting start-ups in developing a SBM. In doing so, the start-ups’ knowledge needs at the beginning of the program and their progress as a result of accelerator participation in developing a SBM are presented. Moreover, we present useful accelerator elements for developing a SBM and an improvement potentials program based on the start-ups’ perspective.

6.1. Overall Importance of Accelerator for Start-Ups’ Success/Development

In general, start-ups attribute a high importance to the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator to support their success/development (see Table 3). While accelerators provide different support elements (e.g., such as resources, knowledge, coaching, and networking) [9], the value of some of these elements are highlighted in the following representative quotes from start-ups that participated in the program.

Table 3.

Importance of the accelerator for start-ups’ success/development as a result of accelerator participation in 2019. Scale: 1 = not important at all; 7 = very important. Source: Item adapted from van Weele et al. [14].

One start-up underlined the benefits of the accelerator in developing a SBM in general: “Sustainability was in the core of our business model from the initial idea, and [the] accelerator helped us to further strengthen our initial decisions.” Another start-up underlined the value of the knowledge transfer for their progress: “We value the knowledge transfer that happens during the program and can admit, that many aspects would not be covered by [the start-up] if not pointed out during the program, making it a valuable experience so far.” More specifically, the effect of learning about the own CO2 footprint and the impact of its own activity on further stakeholders was highlighted by another start-up: “I think that the most important for us was to discover how much CO2 we are saving and what will [the impact on a large scale be].” The value of the network with its benefits for (1) knowledge exchange, (2) emotional support, and (3) business development was underlined by another start-up: “We are happy to be a part of Climate-KIC. Being a part of this community gave us ideas [about] how to implement [the] “eco-dimension” into our offering. Also [it] feels good to be part of [an] eco community where we can instantly reach [out to] each other and share know-how or for [networking purposes].” The value of the financial support provided by the program was also considered very positively by the start-ups.

In general, start-ups stated at the end of the program that being associated with the accelerator brings certain credibility to their activities, which is also important for them (see Table 4). This is in line with Yang et al. [10], who mention that SIAs help start-ups to overcome legitimacy needs by being affiliated with an accelerator and building a brand to raise necessary financial resources. In the case of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator, start-ups are associated with an European institution “EIT Climate-KIC” and the attributes “cleantech,” “sustainability,” being part of a “European network,” belonging to a “community fighting climate change.”

Table 4.

Legitimacy through accelerator participation in 2019. Scale for agreement: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Scale for importance: 1 = not important at all; 7 = very important. Note: SD = standard deviation. Source: Item adapted from van Weele et al. [14].

6.2. Start-Ups’ Knowledge Needs about Sustainability as a Concept

Clarity in knowledge about sustainability as a concept and defining the business’s purpose is essential for becoming a sustainable business [37]. In this regard, start-ups agreed that they had intensely discussed internally what sustainability means for them (see Table 5). However, the high standard deviation of 1.00 indicates a high variety among start-ups’ answers. One start-up describes its knowledge needs as follows: “I think we need help in understanding what exactly sustainability should look like”. In this context, boundary setting is very important by considering in which areas the start-up is active and how far its impact can and should reach to measure ecological and social impacts [1]. This should include relevant time frames and geographies for impact measurement. Given the broad spectrum of aspects, start-ups sometimes feel insecure about their own thinking about the topic and their own ambition level. One representative quote from a start-up illustrates this: “Making sure that we are on the right track or thinking about sustainability in the right way would be useful”. Thus, it seems that start-ups of the accelerator struggle in defining the relevant aspects for their business concerning their goals, how to operationalize them, and how to measure their achievement.

Table 5.

Start-ups’ own knowledge about sustainability as a concept before accelerator participation. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Note: SD = standard deviation. Source: Own item.

6.3. Start-Ups’ Knowledge Needs for Developing a Triple Layered SBM and Progress as a Result of Accelerator Participation

In the following, we present our findings about the start-ups’ knowledge needs concerning each layer at the beginning of the program and their progress in developing a SBM as a result of accelerator participation in 2019.

6.3.1. Economic Layer: Integration of Sustainability Aspect into Business Model

Regarding the characterization of the start-ups’ business model, the SBM archetypes of Bocken et al. were used [3] (see Appendix C). At the beginning of the program, 74.6% of the start-ups indicated that they mainly pursue the development of sustainable business models with a dominant technological innovation component (including Maximize material and energy efficiency, Create value from waste, and Substitute with renewables and natural processes). Only 15.9% of the start-ups followed a SBM archetype with a dominant social innovation component, and 9.5% followed one with a dominant organizational innovation component.

Before participation in the accelerator, start-ups only slightly agreed to have a clear idea of how to integrate the sustainability aspect into their business model (see Table 6). As a result of participation, they indicated progress in this regard and developed a rather clear idea of how to integrate the sustainability aspect into their business model. However, answers still vary among start-ups, since the standard deviation is still high. Before accelerator participation, the knowledge needs ranged from general knowledge about business plan development, as stated by one start-up—“We need to have an expert in the area of business plan development”—to the specifics of developing a SBM as noted by another start-up—“We need the integration of sustainable features into the business model and the marketing of those solutions”.

Table 6.

Start-ups’ knowledge about the integration of the sustainability aspect into their business model before and as a result of accelerator participation. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Note: Value indicates mean ± standard deviation (SD). Source: Own items.

6.3.2. Environmental Layer: Ecological Objectives and Indicators

Before accelerator participation, start-ups only rather slightly agreed to have a clear idea of how to achieve their overall goals in terms of sustainability (see Table 7). The start-ups qualitatively indicated that they need to develop a better understanding of how to define suitable ecological key performance indicators (KPIs) and how to measure them either per target industry, as stated by one start-up—”What are the European KPIs that define each industry as sustainable or not”—or on a product and market level mentioned by another start-up—”We need to identify the relevant sustainability indicators that could be applicable to our product and market”. As a result of accelerator participation, start-ups almost agreed to have much better achieved their goals in terms of sustainability and ecological impact (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Start-ups knowledge about ecological objectives and impact before and as a result of accelerator participation. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree. Note: SD = standard deviation. Source: Own items.

A focus of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator is the support of start-ups that develop solutions for the reduction in CO2 emissions. Therefore, in this study, start-ups of the accelerator were asked regarding their knowledge about (i) their overall environmental impact concerning their resource use (e.g., water and electricity), (ii) whether they know how to calculate their CO2 footprint, and (iii) whether they had already precisely calculated their CO2 footprint in CO2 equivalents (CO2 eq) before participation in the accelerator. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Start-ups’ knowledge about ecological indicators. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Note: Value indicates mean ± standard deviation (SD). Source: Own items.

Before accelerator participation, start-ups only slightly agreed to have an accurate idea of the overall environmental impact of their resource use (e.g., water and electricity) (mean = 4.92; SD = 1.36). Knowledge needs encompass the start-up’s specific selection of the most important ecological indicators as well as the knowledge about the calculation of its ecological impact as one start-up highlights: “We need to know the available models and how to apply [them] or [feedback on whether] our own logic is correct”. As a result of accelerator participation, start-ups indicated progress and developed a more accurate idea in this regard (mean = 5.49; SD = 1.08). The standard deviation was also lower (−0.28), indicating a general increase in start-ups’ knowledge concerning this aspect. However, the standard deviation is still high, so knowledge may differ strongly among start-ups.

In addition, start-ups lacked the relevant knowledge about precisely calculating their own start-ups’ CO2 footprint before participating in the accelerator (mean = 4.21; SD = 1.62). Start-ups reported a general knowledge increase as a result of accelerator participation (+0.77). Yet, even after the end of the program, start-ups only slightly agreed to have a clear idea about how to calculate their start-ups’ CO2 footprint (mean = 4.98; SD = 1.46). It seems that the majority of the start-ups did not calculate their own CO2 footprint in CO2-equivalents neither before (mean = 3.65; SD = 1.79) nor as a result of participation (mean = 4.71; SD = 1.52).

Before accelerator participation, it seems that start-ups’ knowledge needs concerning the ecological layer were very diverse, and they entered the program with very different initial knowledge. Some start-ups had not yet heard about CO2 foot printing before the program, as stated by one start-up: “We don’t have experience in this field; we are not aware of how to calculate it”. Others had already worked on CO2 foot printing beforehand, as reported by another start-up: “We need to gain further knowledge of the CO2 footprint of our production methods. We have carried out approximate life cycle assessment for the products but we need more accuracy”. In addition, start-ups claimed to need more knowledge about (1) relevant data for their analysis, as mentioned by one start-up: “We need actual data and where to gain trustworthy data that is reliable”, (2) handling missing data, and (3) calculation methods for their own CO2 footprint. Moreover, knowledge is needed about the start-up’s direct and indirect emissions.

6.3.3. Social Layer: Social Objectives

The social layer of the start-ups’ business model was not the main focus of the SIA case. As one approximation for the link between societal goals and accelerator participants’ solution, start-ups were asked to indicate their knowledge about their start-ups’ contribution to the UN SDGs before and as result of accelerator participation.

Before accelerator participation, start-ups indicated that they do not have a clear idea about their contribution to the UN SDGs (see Table 9). The start-ups were also asked at the beginning of the program to indicate to which single UN SDG they mainly contribute. Around 12.7% of the start-ups reported that they had not yet thought about the interconnection between their activities and the UN SDGs (see Appendix C).

Table 9.

Start-ups’ knowledge about social objectives before accelerator participation. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Note: Value indicates mean ± standard deviation (SD). Source: Own item developed based on Belz and Peattie [17].

During the program, start-ups progressed in this regard and slightly agreed at the end of the program that they developed a clear idea of how they contribute to the UN SDGs. It seems that the accelerator helped start-ups to link their activities to the UN SDGs, although the standard deviation is very high, and knowledge in this regard still varies considerably among start-ups.

6.4. Integration of Triple Bottom Line into Business Model

In general, successful SBMs are characterized by horizontal coherence of all three layers (economic, environmental, and social) and by vertical coherence between the elements across the different layers [18]. Before accelerator participation, start-ups only slightly agreed to have a clear idea of how their solution contributes to all dimensions of the triple bottom line. As a result of the participation, start-ups almost agreed that they had developed a clear idea of how their solutions contribute to the triple bottom line (see Table 10). However, answers still differ strongly among start-ups as indicated by the high standard deviation.

Table 10.

Start-ups’ knowledge about integration of the triple bottom line into the business model before and as a result of accelerator participation. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Note: Value indicates mean ± standard deviation (SD). Source: Own items.

6.5. Usefulness of Different Accelerator Elements

Providing knowledge for the economic layer through lectures, training, workshops, or e-learning can be seen as a standard service in an accelerator. However, it seems that the highest added value in the accelerator came from the team-specific local coaching as highlighted by one start-up: “Program and mentoring have [a] significant positive effect on our company’s performance. Specific aspects of [the] business model have been updated [;] mentoring has helped for financial planning [and] sales process organization”. For the development of a business plan, start-ups appreciated the guidance of an experienced coach. In general, the planning and reporting activities were considered as being supportive in developing a SBM as stated by one start-up: “Reorganizing our financial/business plan was the focal point in this section [;] it really helped us build a sustainable business model”.

Concerning the ecological layer, start-ups wish to have an “easy-to-use tool” for calculating their CO2 footprint during the program, as mentioned by one start-up: “Provide tools and guidance for the start-ups how to calculate the CO2 footprint of their solution and the environmental footprint”. In general, it seems that most start-ups have great knowledge needs as regards how to calculate their CO2 footprint.

The topic of eco-impact analysis and CO2 foot printing was addressed particularly during the international boot camp (IBC), which was centrally organized by the Center for Industry and Sustainability and at which two team members of all start-ups participated for two days in Frankfurt in Germany. At the international boot camp, international experienced experts gave lectures and training sessions on these topics. In addition, start-ups had plenty of opportunities at the international boot camp to exchange with other participants, potential customers from industry, and alumni of the program. The importance of the international boot camp was highlighted by one start-up in the following statement—“The workshop(s) in Frankfurt mostly helped in these areas. At the boot camp in Frankfurt we had two workshops which were an eye-opener on the subject. One of the workshops was dedicated to CO2 footprint calculation. We now have more useful sources on the subject. We are fully aware of [the] environmental dimension of our new technology”—and by another start-up—“Frankfurt Bootcamp gave [a] good understanding [of] what tools can be used and how they can be [used]”.

Regarding the social layer, one start-up emphasized that the self-reflection exercises during the accelerator were highly valuable for enhancing their understanding how they contribute to the UN SDGs: “That was [the] very first survey that we had to fill in. It forced [us] to think and reflect about [an] SDG and how strongly we [measure up to] it. Also the report was helpful. It allowed [us] to measure the positive impact and think [about] what could be improved”.

The mandatory mid-term report including the SBM exercise was seen positively by the start-ups, as one start-up exemplarily wrote: “In our opinion the Mid-Term Report is a significant milestone document that reflects the previous activities and progress and puts further actions into perspective”. The mandatory reporting activities and exercises were also especially valued in a statement of another start-up: “For us, it is our field, so we already had previous experience around the elements of carbon foot printing and sustainable business modelling. [The exercise] helped [us] to [reflect] on these elements internally […] and consider if there were areas where we could improve even more. So simply HAVING to include it for us was really helpful to reflect and assess our own actions internally not just externally”.

In their feedback concerning the overall program, start-ups underlined the importance of peer-to-peer learning, as one start-up stated: “Meeting with other start-ups and mentors inspired [us] to change the approach”. The exchange with start-ups from the same and other European countries was also positively highlighted by one start-up: “The networking part of the accelerator allowed us to collaborate with other start-ups [locally] and in the future [globally]”. Reflecting about one’s own business model from multiple angles and with various inputs is seen by the start-ups as inspiring and a valuable source for further developing and refining their SBM, and hence as important to consider when designing the program.

6.6. Improvement Potentials for Program

SIAs should take start-ups’ knowledge needs as a starting point for developing their program curriculum, offer, and support elements. In the following, we discuss and provide improvement potentials for SIAs’ curriculum and manual based on the start-ups’ qualitative feedback.

6.6.1. Accelerator Curriculum: Content and Relevant Topics

Concerning necessary market, law, and legislation knowledge for developing sustainable solutions and business models, Table 11 shows start-ups’ knowledge needs in this regard before accelerator participation. The findings identify remarkable differences concerning start-ups’ knowledge needs, which will be subsequently discussed.

Table 11.

Start-ups’ knowledge needs about customers, the market, legislation, and regulation before accelerator participation. Scale: 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree. Note: SD = standard deviation. Source: Own items were developed based on variables for market, law, and legislation knowledge of de Medeiros et al. [19].

Start-ups stated that they have a rather good understanding of customer needs and the value they are generating for customers (value proposition), even though the individual knowledge may vary as the high standard deviation indicates (mean = 5.76; SD = 1.11). As one start-up points out: “We need to better understand our target market needs”. In addition, knowledge about market access options is needed as emphasized by another start-up: “We need contacts to [the] industry to find applications for our technology and validate [those] applications”.

Further, start-ups stated that they have a certain degree of knowledge about their customers’ buying behavior, but some knowledge needs became apparent (mean = 5.43; SD = 1.15). Start-ups especially highlighted that they would need implicit knowledge about the functioning of a market: “We only know how our customers work (in regard to our solution) by what they tell us, we feel that there is much more (politics) going on in the background”. Another start-up stated: “We need background knowledge of the industry”. Without understanding the customers’ buying behavior, start-ups cannot adequately interact with potential customers or sell the value of a sustainable solution to a customer, as exemplarily underlined by one start-up: “It is often difficult to communicate sustainability and why it’s important to clients in [the] industry”.

The start-ups’ self-assessment reveals knowledge needs about (environmental) laws and legislation (mean = 5.29; SD = 1.39). To gain financial and support from public institutions, it is important that the start-ups are able to demonstrate to governmental authorities how they can contribute to environmental and social goals, and how they comply with legislation. Financial and information support from governments can help start-ups to identify and apply for upcoming funding options, or to consider changes in the regulatory environment that will impact their activities. Having access to this information likely increases start-ups’ ability to identify promising markets niches and develop competitive offers.

In addition, start-ups lack knowledge about the market’s perception of sustainability (mean = 5.22; SD = 1.21). Especially, knowledge about customers’ internal decision-making processes is of importance so that start-ups can align their value selling on the most important decision criteria of a customer. The statement of one start-up illustrates this knowledge need: “Knowledge [is] required regarding [how] we can successfully mix our service solution with CSR programs”. This statement shows the start-up’s assumption that they can successfully sell their product if they are able to create a connection between companies’ CSR programs and their own offer.

Start-ups stated that they have the least knowledge about their customers’ willingness to pay for sustainable solutions (mean = 4.63; SD = 1.37). This is a remarkable result, as knowledge about value drivers is the foundation for capturing the delivered economic value through setting the right price, which positively influences the start-ups’ revenue streams. In this regard, start-ups indicated that they require knowledge about how to sell the eco-value of their solution, as one start-up says: “Help start-ups to demonstrate and communicate the eco-impact of their proposed solution towards their customers”. Another start-up formulates this as follows: “[The] start-ups [need to be trained] to sell the eco-value of their proposed solution”.

Overall, the ratings in Table 11 show that start-ups have the greatest knowledge needs regarding potential customers’ willingness to pay, their market perception of sustainability, and the law and legislation. Therefore, these topics should be considered in SIAs’ curricula.

6.6.2. Accelerator Manual: Support Elements for Program Delivery

In particular, start-ups see an improvement potential of the program in providing more team-specific coaching. All teams receive 20 h of individual coaching from a local coach during the program, but they wish to have “more hands-on workshops with real-life experts”, as emphasized by one start-up.

Accelerator managers have to evaluate this suggestion from a cost–benefit perspective. While an individual coaching may be very effective in solving team-specific challenges, it is associated with high costs. In addition, depending on the specific knowledge needs of the start-ups and the availability of qualified coaches in a region, the selection of adequate coaches may represent a challenge. It may become increasingly difficult to find suitable coaches on a regional level, the more advanced the challenges of the start-ups are, the more industry-specific knowledge and experience is needed, and the more specialized knowledge about the specifics of geographic markets or technologies may be required. A potential solution to this problem could be the consideration of more international coaches and a higher use of virtual meetings for coaching sessions. This approach could help to find suitable coaches with the highest expertise and value for start-ups.

Regarding the ecological layer, start-ups propose to have (1) easy-to-use tools for eco-impact assessment and (2) more boot camps focusing on this topic, as suggested by one start-up: “[In] our perspective, more […] boot camps for training on these aspects [are needed], practically and concentrated”.

The start-ups did not indicate any improvement options for the social layer. Indeed, the UN SDGs should be a main reference for SIAs to demonstrate their impact for societal goals. SIAs should promote the UN SDGs and draw the attention of participating start-ups to them. For instance, SIAs could highlight the UN SDGs’ and their societal importance with different activities and events.

Concerning the integration of all three layers of a SBM, improvement potential was mentioned concerning the amount of feedback from relevant stakeholders on the start-ups’ solution, as indicated by various start-ups and exemplarily stated by them as follows: “We would like to get […] feedback from as many experts in the field regarding our business model” and “[We want] feedback on our way of thinking and doing business”. Start-ups also wished to increase and intensify the number of connections with different stakeholders, as pointed out by one start-up—“More local and international networking opportunities would be great”—or by another start-up—“more connections with large companies which could use/integrate our solutions”.

7. Discussion

7.1. Implications for Theory and Limitations of this Study

We aim to help in understanding how a SIA can be optimally designed. In doing so, we here described the intended function of one SIA case with its different accelerator design elements and presented the support elements that reduce start-ups’ knowledge needs in developing a SBM. Further, the efficacy of different accelerator elements were assessed based on quantitative ratings and qualitative data from 63 European start-ups that participated in the same accelerator batch in 2019 and were generally in an early development phase. Our findings on start-ups’ knowledge needs for developing a triple layered SBM may be further elaborated in future studies, as our study has several limitations.

In this study, we only addressed some aspects of each layer and mainly focused on the economic and ecological layers. Thus, further research that investigates the different single layers and their interconnectedness, considering more elements and aspects of each single layer of a SBM, is necessary. For instance, the Triple Layered Business Model Canvas (TLBMC) of Joyce and Paquin [18] could be used in this context. In doing so, research must also take into account the rebound effects of SBM innovation [1].

In addition, we analyzed start-ups’ knowledge needs on a pan-European basis and did not take into account any regional specifics of the 12 European RIS countries, and only 63 of the 83 start-ups from the program participated in the study. Thus, our data sample is not representative of all participating start-ups from the accelerator batch in 2019, nor of all cleantech start-ups in Europe. Therefore, future research could focus on regional specifics. For instance, Pauwels et al. argue that different contexts (e.g., policy, industry, density, and economic conditions in a particular region) in which accelerators operate may require a distinct focus and function of accelerators [22].

Finally, further research on different accelerator elements, their interplay, and their individual and combined efficacy is necessary, since we only present one case. This would generally enhance our understanding of the intermediary role of support forms such as SIAs for start-ups. In doing so, research could support accelerators to enhance and optimize their curriculum, support services, and intervention mechanisms and help to select suitable start-ups based on their program offers.

7.2. Implications for Accelerator Stakeholders and Managers

The findings of this study could inform and help accelerator managers of SIAs to reflect on and enhance their own program. Other stakeholders from the innovation ecosystem may also benefit from our findings in terms of how to design start-up support programs with a focus on sustainability (e.g., policy makers).

Concerning the curriculum of the program, our study identified the importance of different sets of knowledge in developing a SBM, especially focusing on the economic and environmental layers. On the economic layer of a SBM, this study identified that start-ups have the greatest knowledge needs with regard to an understanding of the sustainable buying behavior of their customers, including the customers’ willingness to pay for sustainable solutions and the general market perception of sustainability. In addition, start-ups need knowledge about law and legislation and the current regulatory developments in their market environment. Regarding the environmental layer, knowledge about CO2 footprint analysis is needed. Start-ups wish to have reliable and easy-to-use tools for calculating CO2 footprints (their own, their suppliers’, and their customers’). Concerning the social layer, start-ups have not defined improvement potentials. However, the UN SDGs may be used to demonstrate a start-up’s societal impact (e.g., operationalized by their contribution to the UN SDGs).

In general, accelerators should provide sufficient tailored support elements to start-ups when developing a SBM according to the specific start-up knowledge needs considering the triple bottom line. In particular, start-ups appreciated the local coaching, interactive workshops and events (e.g., the International Boot Camp of the program), and exchanging and learning from their peers during the program. Thus, these accelerator elements should be especially considered by accelerator stakeholders and managers when designing a SIA.

8. Conclusions

SIA are a relatively new phenomenon that can help start-ups to develop a SBM [10]. This is the very first study to our knowledge that investigates how a SIA supports start-ups’ in developing a SBM. Thus, we elucidate the intermediary role of SIAs in supporting start-ups and developing a SBM by presenting the case study of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator and qualitatively assessing the efficacy of different accelerator elements from the start-ups’ perspective. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for those who research, fund, setup, manage, and operate SIAs and provide guidance in terms of how to adapt a SIAs’ manual, curriculum, and elements in practice to support start-ups in developing a SBM. Our findings could also serve as a steppingstone to future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.B. and H.U.; Data curation, T.B. and H.U.; Formal analysis, T.B. and H.U.; Investigation, T.B. and H.U.; Methodology, T.B. and H.U.; Writing—original draft, T.B. and H.U.; writing—review and editing, T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors did not receive any funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Design of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator

Table A1.

Source: Own representation based on Cohen et al. [13], as well as data, curriculum, and manual of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator from 2019. Note: Table continues on the following pages.

Table A1.

Source: Own representation based on Cohen et al. [13], as well as data, curriculum, and manual of the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator from 2019. Note: Table continues on the following pages.

| Choice | Theoretical Options | Importance | EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program in 2019 | Additional Information and Data | |||

| Cohort size | The number of start-ups in each cohort | The number of start-ups in each cohort influences the resources available to each firm and the level of interactions between firms. Some programs have strict cohort size limits, while others fluctuate based on the strength of the admission pool or available funding. | 83 start-ups from 12 European countries | Competitive selection process:

|

| Cohort composition | Generic, or focused by industry or founder characteristics, including gender or ethnicity | Homogenous cohorts may provide higher levels of specialized information but may also promote competitive behaviors. Limiting selection to a particular demographic may reduce the size and thus the quality of the selection pool. | Cleantech start-ups with sustainable business models in 3 different development stages | Stage 1: Business model development (N = 28 start-ups) Stage 2: Business model validation and refinement, market segmentation, and first customers (N = 37 start-ups) Stage 3: Up-scale and investor search (N = 18 start-ups) |

| Program duration | Between 4 weeks and one year | Program duration may adjust to product development lifecycle with those targeting longer-cycle industries having longer programs. | 6 months | Each stage is 6 months |

| Funding provided | The amount provided, when it is provided, from whom it is provided, and the terms on which it is given. Ranges from USD 0–USD 600 K | Funding provides incentives for entrepreneurs to participate in programs and allows them to commit full time to a program. It also allows start-ups to acquire additional resources. | Up to 50 K EUR Dependent on the achievement of defined key milestones during the program | Stage 1: up to 10 K EUR Stage 2: up to 15 K EUR Stage 3: up to 50 K EUR |

| Equity taken | Between none and 15% | Equity may align accelerator interests with founders. | No equity taken | Public funding of program through an European institution (EIT Climate-KIC) under Horizon 2020 |

| Mentorship | Who provides the mentorship, frequency, and timing of mentor interactions | The quality and number of mentors may influence what the start-up is able to learn, as well as its access to other partners. | Start-ups receive 20 h of professional coaching. Additionally, voluntary mentors support the start-ups. | Locally by experienced practitioners |

| Advisory and managing directors | Backgrounds of accelerator and start-up founders | The background of the accelerator founders and managing directors influences the social networks and knowledge available to the participating start-ups. The number of and composition of the accelerator’s management team impact the number of portfolio start-ups or the services provided. | Orchestration, implementation, and execution of program through joint collaborative approach: Central steering by one organization and local delivery of program with 12 European partners. | The accelerator was created as a result of a co-creation approach by Center for Industry and Sustainability (conceptual lead) and various national accelerator program managers from different European countries, designing together the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator program in 2016. The sign-off of the developed program was done by the EIT Climate KIC RIS director. The central steering organization creates framing documents for the program (e.g., curriculum, manual, and other guidelines) and provides funding for the start-ups (including contract management). Local partner organizations are responsible for the national promotion of program and recruitment of applicants plus the design of local program elements (e.g., coaching, workshops, training, and boot camps). |

| Educational programming | Required structured educational programming or a-la-carte offerings | Structured programing can be time-consuming, but also provides comprehensive foundational education for start-up founders. More experienced founders may prefer a-la-carte-style programs but may lead to knowledge gaps since founders are not always accurate in their self-assessment. | Structured curriculum with flexible elements: 80% of the activities are standardized across all countries, and 20% of the activities are locally adapted to reflect and meet the local specifics of the regional ecosystem in each RIS country. | Curriculum was developed and is based on the lean start-up method (Ries, 2011). Additionally, the focus is set on the development of sustainable business models. Educational programming includes local coaching plus local and international training, workshops, and boot camps. |

| Co-working space | Accelerators provide open, flexible co-working space, silo-style office space or no space | Space provides instant access to peer firms and attracts other resource providers, including mentors to the central location. However, some argue that co-working space could lead to unproductive co-dependency. | Co-working spaces are provided by some local partners, but not part of the program’s services. | If local partners do not provide co-working spaces, start-ups must rent working/office space on their own or must use private co-working spaces from commercial providers. |

| Graduation event, such as Demo day | Demo days with investors; conferences or prize competitions | Graduation events demark the end of the program and provide a vehicle for launching nascent start-ups to investors or the marketplace. They also provide exposure for the accelerators. | National demo day or investor dinner | These events are independently organized by each local partner, and offers may vary from partner to partner. |

| Program location | Geographic location | The composition of the local regional ecosystem influences the type of start-ups that apply to the program and the resources including mentors, as well as access to local knowledge via spillovers. | In 12 European countries: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, and Slovenia. | Local partners are mostly located in the capital or industrial or science hotspots of the respective country, and thus provide access to the local regional ecosystem, but participating start-ups have access to other national ecosystems and an international (peer-to-peer) network due to the European dimension of the program |

| External Stakeholders (sponsors) | Corporation Governments Academia Investors | External stakeholders who provide resources to accelerators in exchange for preferential access to participating start-ups differ in their reasons for affiliating with a start-up and may influence accelerator outcomes. Corporations use accelerators to scan the environment for new technologies and markets or promote their own products and services, governments promote in regional development, academic programs use accelerators as a vehicle to either transfer technology or develop student skills, and investors use accelerators to vet potential investments. | EIT Climate-KIC is the financial sponsor of the program and pursues the goal to support solutions that mitigate consequences of climate change for a decarbonized and sustainable economy | Matchmaking website for corporates and investors plus other central and local activities, but networking and matchmaking activities are mainly conducted at the local level. Promotion of success stories for international branding of the program to attract external sponsors or relevant stakeholders for the successful development of the start-ups. |

Appendix B. Accelerator Elements and Their Contribution for Developing a SBM

Table A2.

Source: Own representation based on the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator’s curriculum and manual in 2019 (all mandatory elements are ca. 75 h in total). Note: Table continues on the following pages.

Table A2.

Source: Own representation based on the EIT Climate-KIC RIS Accelerator’s curriculum and manual in 2019 (all mandatory elements are ca. 75 h in total). Note: Table continues on the following pages.

| Accelerator Element | Description | Delivery Mode | Hours | Contribution to SBM Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Provide New Knowledge to Start-Ups: Training/Lectures | ||||

| On-boarding workshop | Workshop to introduce the rules of the program (e.g., contractual relationship with milestones; need to define milestones; need to report on startup’s progress on milestones; need to work on the sustainable business model exercise; requirements of cost reporting) | Locally organized; typical participants: all start-ups of one region, local designated coach; regional partner organization | 1 × 8.0 h |

|

| National workshops/ training | Active/participatory workshops/ training, which often provide practical and hands-on knowledge, or are related to a specific topic. | Locally organized | two 1-day workshops á 8.0 h = 16.0 h |

|

| International boot camp | Boot camps are very practical and provide workshops, training, and networking. Usually boot camps are more intense than workshops, and they often take place over several days. | Centrally organized by Center for Industry and Sustainability | 2.5 days × 8.0 h = 20.0 h |

|

| International EIT Climate-KIC Masterclass | In a Masterclass, a (well-known) expert teaches relevant knowledge. They have often a workshop format and their duration can differ. In EIT Climate-KIC, several Masterclasses are offered at different locations throughout the year. | Organized by EIT Climate-KIC across all locations | Voluntary participation of start-ups |

|

| e-learning | EIT Climate-KIC offers a free-of charge e-learning platform with short webinars on such topics as climate impact assessment or business model canvas. | Provided by EIT Climate-KIC | Voluntary participation of start-ups |

|

| (1) Provide New Knowledge to Start-Ups: Matchmaking | ||||

| Matchmaking events | Several matchmaking options are integrated in the program, e.g., matchmaking as part of the international boot camp with stakeholders from industry and investors. At the European level, possible options for matchmaking are highlighted and communicated during the program or on the matchmaking website (e.g. European Chemistry Partnering in 2019). | Locally or centrally organized | Optional |

|

| Matchmaking website | Start-ups present their offer based on a standardized template on the matchmaking website (description of solution and value proposition, market, business model, and target): http://matchmaking-startups-cleantech.eu/ (accessed on 16 March 2021) | Centrally organized by Center for Industry and Sustainability | Voluntary participation of start-ups |

|

| (2) Support Start-Ups’ Assimilation of New Knowledge: Coaching/Mentoring | ||||

| Individual coaching | Each start-up has a designated coach supporting the start-up’s development. In addition to giving practical advice, the coach helps in developing and implementing the start-ups’ contractual milestones of and comments on the start-up’s progress towards the local partner and the central steering organization. Coaches are normally financed by the program. Center for Industry and Sustainability provides a support chart pool for local coaches for voluntary use regarding methodologies and cases for the development of sustainable business models. | Locally organized and crucial part of the accelerator program—the local coaching is supported with a central diagnosis tool and can use learning materials, which are also centrally provided. Local coach should select and use the right and appropriate methods and learning materials for the respective start-up depending on its stage and knowledge. | 10 coaching sessions á 2.0 h every two weeks = 20.0 h |

|

| Mentoring | Mentoring is a more informal relationship in which the mentor empowers and enables the mentee by sharing experiences and resources. Mentoring is long-term, and mentors often work pro bono. | Not part of the program, mentoring is locally organized by the local partners as an “add-on” | Optional |

|

| (2) Support Start-Ups’ Assimilation of New Knowledge: Reflection and Evaluation | ||||

| Beginning of the program (On-boarding) | At the beginning of the program, all start-ups are asked to describe their expectations for the program as well as their perceived knowledge needs for developing a SBM. | Online questionnaire | Ca. 0.5 h |

|