The Political Market and Sustainability Policy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

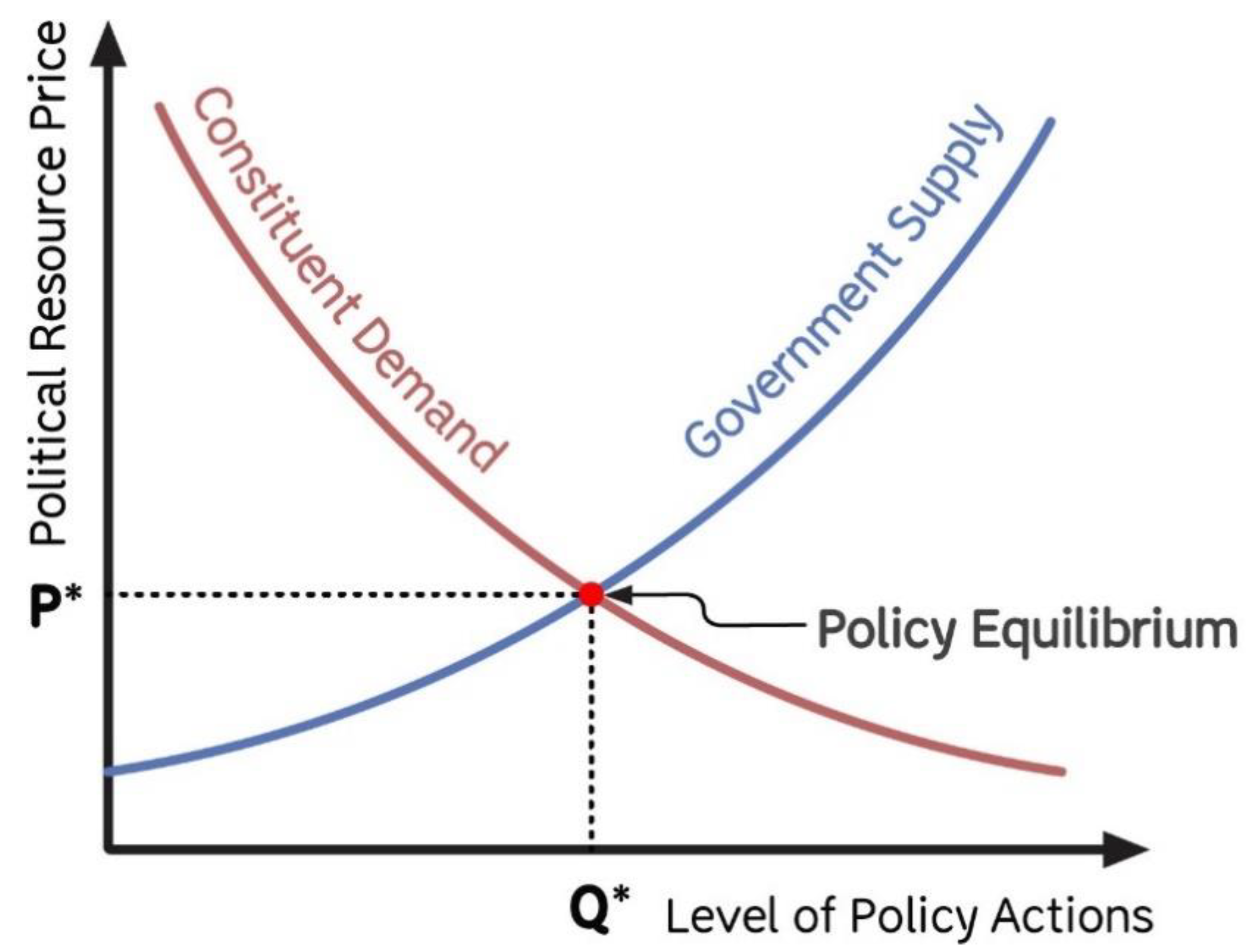

2. The Political Market Approach

3. Transaction Costs

4. The Role of Institutions

5. Policy Choice and Program Design

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerber, E. The Populist Paradox; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.E.; DeLeo, R.A.; Taylor, K. Policy entrepreneurs, legislators, and agenda setting: Information and influence. Policy Stud. J. 2020, 4, 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, M. The Political Economy of Public Administration: Institutional Choice in the Public Sector; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Scartascini, C. The Institutional Determinants of Political Transactions; Research Department Working paper series; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A. The Making of Economic Policy: A Transaction Cost Politics Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grindle, M.; Thomas, J. Policy makers, policy choices and policy outcomes: The political economy of reform in developing countries. Policy Sci. 1989, 22, 213–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haelg, L.; Sewerin, S.; Schmidt, T. The role of actors in the policy design process: Introducing design coalitions to explain policy output. Policy Sci. 2020, 53, 309–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Feiock, R.C.; Ramirez, E. Political institutions and conservation by local governments. Urban Aff. Rev. 2005, 40, 706–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M.; Feiock, R.C.; Ramirez, E. Local institutions and the politics of urban growth. Am. J. Political Sci. 2009, 53, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, S. Regional integration through contracting networks: An empirical analysis of institutional collection action framework. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009, 44, 378–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.; Zhao, Z.; Feiock, R.C.; Ramaswami, A. Patterns of urban infrastructure capital investment in Chinese cities and explanation through a political market lens. J. Urban Aff. 2019, 41, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.F.; da Cruz, N.F. Explaining the transparency of local government websites through a political market framework. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101249–101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, J. Transaction costs and the normative elements of the public choice model: An application to constitutional theory. VA Law Rev. 1998, 74, 471–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, O. Transaction cost economics: How it works; where it is headed. Economist 1998, 146, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libecap, G. Contracting for Property Rights; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Alchian, A.; Demsetz, H. Production, information costs, and economic organization. Am. Econ. Rev. 1973, 62, 777–795. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, L.J. Empirical work in institutional economics. In Empirical Studies in Institutional Change; Alston, L.J., Eggertsson, T., North, D.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, F.; Jones, B. Agendas and Instability in American Politics; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, M. Network structures and spinoff effects in a collaborative public programs. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 42, 976–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frant, H. High-powered and low-powered incentives in the public sector. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1996, 6, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, S.M. Constitutions as relational contracts: Explaining procedural safeguards in municipal charters. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1998, 8, 527–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. A Quasi-market framework for local economic development competition. J. Urban Aff. 2002, 24, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A. Managerial friction and land-use policy punctuations in the fragmented metropolis. Policy Stud. J. 2018, 48, 700–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Impact Fees Decision Mechanism: Growth Management Decisions in Local Political Market. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2010, 15, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riker, W. Liberalism Against Populism: A Confrontation Between the Theory of Democracy and the Theory of Social Choice; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Feiock, R. Rational Choice and Regional Governance. J. Urban Aff. 2007, 29, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Teske, P. Toward a theory of the political entrepreneur: Evidence from local government. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1992, 86, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, C.; Feiock, R.C.; Xu, K. Policy analysis of instrument design: How policy design affects policy constituency. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2020, 22, 536–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. Public and private bureaucracies: A transaction cost economics perspective. J. Lawecon. Organ. 1999, 15, 306–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stokan, E.; Deslatte, A. Beyond borders: Governmental fragmentation and the political market for growth in American cities. State Local Gov. Rev. 2019, 51, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clingermayer, J. Choice of constituency and representation in urban politics. Mid-Am. J. Politics 1985, 2, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, J.B. What have we learned about the performance of council-manager government? A review and synthesis of the research. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.B.; Karuppusamy, S. The adapted cities framework: On enhancing its use in empirical research. Urban Aff. Rev. 2008, 43, 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Feiock, R.C. The Collaboration risk scape: Fragmentation, problem types and preference divergence in urban sustainability. Publius J. Fed. 2019, 49, 352–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deslatte, A. Citizen assessments of local government sustainability performance: A Bayesian approach. J. Behav. Public Adm. 2019, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, R.K.; Shepard, W.B. Political processes and public expenditures: A re-examination based on theories of representative government. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1976, 70, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, M. Collaborative institutions, belief systems, and perceived policy effectiveness. Political Res. Q. 2003, 56, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D. Empirical research on local government sustainability efforts in the USA: Gaps in the current literature. Local Environ. 2009, 14, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurian, L.; Walker, M.; Crawford, J. Implementing environmental sustainability in local government: The impacts of framing, agency culture, and structure in US cities and counties. Int. J. Public Adm. 2017, 40, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Integrating mediators and moderators in research design. Res. Soc. Work Pr. 2011, 21, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feiock, R.C.; Tavares, A.F.; Lubell, M. Policy instrument choices for growth management and land use regulation. Policy Stud. J. 2008, 36, 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Ramírez, C.E.E. Local political institutions and smart growth: An empirical study of the politics of compact development. Urban Aff. Rev. 2009, 45, 218–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, E.R.; Phillips., J.H. Direct democracy and land use policy: Exchanging public goods for development rights. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, R.B.; Oakerson, R.J. Metropolitan organization and governance: A local public economy approach. Urban Aff. Q. 1989, 25, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schattschneider, E.E. The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist’s View of American Democracy; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Clingermayer, J.C.; Feiock, R.C. Institutional Constraints and Local Policy Choices: An Exploration of Local Governance; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.; Feiock, R. Forms of government and climate change policies in U.S. cities. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C. Competing interests and the political market for smart growth policy. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2503–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Yi, H. Complementarity and substitutability: A review of state level renewable energy policy instrument interactions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 67, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R. Politics, institutions and local land-use regulation. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiock, R.C. City scale vs. regional scale co-benefits of climate and sustainability policy: An institutional collective action analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Nat. Resour. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feiock, R.C.; Kim, S. The Political Market and Sustainability Policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063344

Feiock RC, Kim S. The Political Market and Sustainability Policy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063344

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeiock, Richard C., and Soyoung Kim. 2021. "The Political Market and Sustainability Policy" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063344

APA StyleFeiock, R. C., & Kim, S. (2021). The Political Market and Sustainability Policy. Sustainability, 13(6), 3344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063344