Differences in Occurrence of Unethical Business Practices in a Post-Transitional Country in the CEE Region: The Case of Slovakia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Research Context

2.2. Unethical Practices in Business

2.3. Differences in Occurrence of Unethical Practices in Business

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Method and Scale Development

3.2. Sampling Strategy and Procedure of Data Acquisition

3.3. Sample Demographics in Brief

3.4. Grouping Variables

3.5. Test Variables

3.6. Preliminary Data Analysis

4. Research Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Cronbach’s Alpha Based on Standardized Items | N of Items | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.966 | 0.965 | 26 | ||||

| Mean | Min. | Max. | Range | Max/Min | Variance | |

| Item Means | 3.082 | 2.429 | 3.951 | 1.521 | 1.626 | 0.183 |

| Reliability analysis for the 26 UBPs (individual items) | ||||||

| Scale Mean if Item Deleted | Scale Variance if Item Deleted | Corrected Item-Total Correlation | Squared Multiple Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted | ||

| UBPbuspart1_Non-payment | 76.17 | 709.136 | 0.458 | 0.583 | 0.966 | |

| UBPbuspart2_Non-compliance with contracts | 76.42 | 703.445 | 0.529 | 0.631 | 0.966 | |

| UBPbuspart3_Corrupt behavior of business partner | 77.01 | 695.438 | 0.616 | 0.551 | 0.965 | |

| UBPbuspart4_Abuse of the position of large companies against the small comp. | 76.33 | 700.412 | 0.596 | 0.564 | 0.965 | |

| UBPbuspart5_Nepotism in the business environment | 76.54 | 701.817 | 0.566 | 0.478 | 0.965 | |

| UBPbuspart6_Purposeful bankruptcy | 77.20 | 692.308 | 0.645 | 0.534 | 0.965 | |

| UBPcust1_Sale of poor-quality products or services | 76.87 | 685.817 | 0.737 | 0.768 | 0.964 | |

| UBPcust2_Avoiding liability for complaints and errors | 76.78 | 687.618 | 0.724 | 0.754 | 0.964 | |

| UBPcust3_Misleading advertising, deception | 76.69 | 684.361 | 0.741 | 0.752 | 0.964 | |

| UBPcompet1_Abuse of a strong market position, cartel agreements | 76.53 | 691.042 | 0.702 | 0.678 | 0.964 | |

| UBPcompet2_Unfair procurement practices | 76.60 | 687.453 | 0.742 | 0.702 | 0.964 | |

| UBPcompet3_Patent abuse, theft of ideas/brands | 77.20 | 691.947 | 0.712 | 0.651 | 0.964 | |

| UBPcompet4_Purposeful damaging of competitors’ reputation | 77.00 | 688.280 | 0.737 | 0.668 | 0.964 | |

| UBPempl1_Employee discrimination | 77.48 | 690.840 | 0.708 | 0.638 | 0.964 | |

| UBPempl2_Unlawful wage-paying practices | 77.36 | 680.467 | 0.762 | 0.734 | 0.964 | |

| UBPempl3_Failure to comply with employee levies-related obligations | 77.64 | 680.422 | 0.782 | 0.773 | 0.964 | |

| UBPempl4_Failure to respect employees’ privacy at the workplace | 77.57 | 693.657 | 0.649 | 0.616 | 0.965 | |

| UBPempl5_Unethical behavior towards employees (indecent, unfair, arrogant) | 77.37 | 686.591 | 0.724 | 0.740 | 0.964 | |

| UBPempl6_Bad work conditions | 77.56 | 687.656 | 0.736 | 0.750 | 0.964 | |

| UBPempl7_Persecution of whistle-blowers | 77.69 | 688.339 | 0.747 | 0.707 | 0.964 | |

| UBPstate1_Failure to comply with applicable laws | 77.26 | 680.529 | 0.792 | 0.773 | 0.964 | |

| UBPstate2_Non-payment of taxes, tax fraud | 77.34 | 676.111 | 0.803 | 0.823 | 0.963 | |

| UBPstate3_Corruption of civil servants | 77.22 | 677.277 | 0.807 | 0.844 | 0.963 | |

| UBPstate4_Misuse of contacts with politicians and officials | 76.99 | 678.193 | 0.790 | 0.856 | 0.964 | |

| UBPstate5_Unfair practices in obtaining public contracts, public/euro funds | 76.99 | 676.824 | 0.790 | 0.852 | 0.964 | |

| UBPstate6_Environmental damages | 77.21 | 683.078 | 0.768 | 0.719 | 0.964 | |

| Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| UBP Business partners (UBPbuspart) | 0.867 | 6 |

| UBP Customers (UBPcust) | 0.929 | 3 |

| UBP Competitors (UBPcompet) | 0.900 | 4 |

| UBP Employees (UBPempl) | 0.942 | 7 |

| UBP State/society (UBPstate) | 0.959 | 6 |

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Var. | Cumul. % | Total | % of Var. | Cumul. % | Total | % of Var. | Cumul. % | |

| 1 | 14.101 | 54.235 | 54.235 | 14.101 | 54.235 | 54.235 | 5.351 | 20.580 | 20.580 |

| 2 | 2.482 | 9.546 | 63.781 | 2.482 | 9.546 | 63.781 | 5.219 | 20.072 | 40.652 |

| 3 | 1.295 | 4.980 | 68.761 | 1.295 | 4.980 | 68.761 | 5.063 | 19.471 | 60.124 |

| 4 | 1.204 | 4.629 | 73.390 | 1.204 | 4.629 | 73.390 | 3.449 | 13.266 | 73.390 |

| ... | ... | ... | |||||||

| 26 | 0.088 | 0.340 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Rotated Component Matrix | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| UBPbuspart1_Non-payment | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.127 | 0.842 |

| UBPbuspart2_Non-compliance with contracts | 0.138 | 0.189 | 0.120 | 0.826 |

| UBPbuspart3_Corrupt behavior of business partner | 0.179 | 0.358 | 0.205 | 0.641 |

| UBPbuspart4_Abuse of the position of large comp. against small | 0.109 | 0.494 | 0.141 | 0.584 |

| UBPbuspart5_Nepotism in the business environment | 0.279 | 0.441 | 0.32 | 0.496 |

| UBPbuspart6_Purposeful bankruptcy | 0.158 | 0.405 | 0.292 | 0.561 |

| UBPcust1_Sale of poor-quality products or services | 0.319 | 0.748 | 0.213 | 0.195 |

| UBPcust2_Avoiding liability for complaints and errors | 0.316 | 0.757 | 0.190 | 0.187 |

| UBPcust3_Misleading advertising, deception | 0.281 | 0.789 | 0.233 | 0.175 |

| UBPcompet1_Abuse of a strong market position, cartel agreements | 0.123 | 0.706 | 0.317 | 0.298 |

| UBPcompet2_Unfair procurement practices | 0.131 | 0.654 | 0.429 | 0.305 |

| UBPcompet3_Patent abuse, theft of ideas/brands | 0.249 | 0.660 | 0.303 | 0.234 |

| UBPcompet4_Purposeful damaging of competitors’ reputation | 0.289 | 0.667 | 0.297 | 0.240 |

| UBPempl1_Employee discrimination | 0.744 | 0.303 | 0.207 | 0.169 |

| UBPempl2_Unlawful wage-paying practices | 0.663 | 0.217 | 0.449 | 0.204 |

| UBPempl3_Failure to comply with employee levies-related obligations | 0.687 | 0.230 | 0.458 | 0.190 |

| UBPempl4_Failure to respect employees’ privacy at the workplace | 0.801 | 0.177 | 0.205 | 0.124 |

| UBPempl5_Unethical behavior towards employees (indecent, unfair) | 0.813 | 0.249 | 0.253 | 0.126 |

| UBPempl6_Bad work conditions | 0.780 | 0.211 | 0.344 | 0.132 |

| UBPempl7_Persecution of whistle-blowers | 0.704 | 0.266 | 0.388 | 0.128 |

| UBPstate1_Failure to comply with applicable laws | 0.445 | 0.273 | 0.678 | 0.189 |

| UBPstate2_Non-payment of taxes, tax fraud | 0.436 | 0.228 | 0.745 | 0.199 |

| UBPstate3_Corruption of civil servants | 0.345 | 0.295 | 0.799 | 0.169 |

| UBPstate4_Misuse of contacts with politicians and officials | 0.323 | 0.290 | 0.801 | 0.163 |

| UBPstate5_Unfair practices in obtaining public contracts, euro funds | 0.286 | 0.318 | 0.813 | 0.158 |

| UBPstate6_Environmental damages | 0.390 | 0.292 | 0.706 | 0.141 |

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov a | Shapiro–Wilk | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | df | Sig. | Statistic | df | Sig. | |

| UBP Total | 0.45 | 1295 | 0.00 | 0.977 | 1295 | 0.00 |

| UBP Bus. Partners | 0.83 | 1295 | 0.00 | 0.956 | 1295 | 0.00 |

| UBP Customers | 0.151 | 1295 | 0.00 | 0.905 | 1295 | 0.00 |

| UBP Competitors | 0.103 | 1295 | 0.00 | 0.941 | 1295 | 0.00 |

| UBP Employees | 0.112 | 1295 | 0.00 | 0.932 | 1295 | 0.00 |

| UBP State/Society | 0.109 | 1295 | 0.00 | 0.913 | 1295 | 0.00 |

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 695 | 53.7 |

| Female | 600 | 46.3 | |

| Age | Up to 30 years | 121 | 9.3 |

| 31–40 years | 298 | 23.0 | |

| 41–50 years | 394 | 30.4 | |

| 51–60 years | 339 | 26.2 | |

| More than 60 years | 143 | 11.0 | |

| Field of study | Economics/Management | 610 | 47.1 |

| Law | 70 | 5.4 | |

| Natural Sciences | 49 | 3.8 | |

| Social Sciences | 113 | 8.7 | |

| Technical | 371 | 28.6 | |

| Other | 82 | 6.3 | |

| Level of education | Primary education | 4 | 0.3 |

| Secondary education | 224 | 17.3 | |

| Bachelor | 113 | 8.7 | |

| Master | 813 | 62.8 | |

| Ph.D. | 141 | 10.9 | |

| Position | Company owner/Director | 537 | 41.5 |

| Top manager | 320 | 24.7 | |

| Manager | 66 | 5.1 | |

| Ethics & Compliance manager | 19 | 1.5 | |

| Internal lawyer | 11 | 0.8 | |

| Internal auditor | 10 | 0.8 | |

| Ethics officer | 5 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 327 | 25.3 | |

| Seniority | Less than 1 year | 84 | 6.5 |

| 1–3 year | 220 | 17.0 | |

| 4–10 years | 379 | 29.3 | |

| More than 10 years | 612 | 47.3 | |

| N Stat. | Range | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std.Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Sector | 1295 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 5.48 | 3.141 | 0.286 | −1.448 |

| Membership in PNs | 1166 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.496 | 0.267 | −1.932 |

| Ownership | 1242 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.07 | 0.259 | 3.302 | 8.919 |

| Company Age | 1295 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 4.06 | 1.381 | −0.298 | −1.072 |

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Sector | Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing | 67 | 5.2 |

| Manufacturing, Mining and Quarrying and other industries | 235 | 18.1 | |

| Construction | 125 | 9.7 | |

| Wholesale Trade, Retail Trade, Transportation and Warehousing, Accommodation and Food Services | 251 | 19.4 | |

| Information and Communication | 87 | 6.7 | |

| Finance and Insurance | 45 | 3.5 | |

| Real Estate-related activities | 22 | 1.7 | |

| Professional, Scientific, Technical, Administrative and Support Services | 112 | 8.6 | |

| Public Administration, Defense, Education, Healthcare and Social Assistance | 88 | 6.8 | |

| Other Services | 263 | 20.3 | |

| Membership in PNs | Non-member | 660 | 51.0 |

| Member | 506 | 39.1 | |

| N/A (missing) | 129 | 10. | |

| Ownership | Private | 1152 | 89.0 |

| Public | 90 | 6.9 | |

| N/A (missing) | 53 | 4.1 | |

| Company Age | 0–3 years | 23 | 1.8 |

| 4–10 years | 204 | 15.8 | |

| 11–15 years | 255 | 19.7 | |

| 16–20 years | 191 | 14.7 | |

| 21–30 years | 431 | 33.3 | |

| 30+ years | 191 | 14.7 | |

| Mean | Std.Dev. | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBP Total (composite, all items) | 3.08 | 1.049 | 1.100 | −0.22 | −0.908 |

| UBP Business partners (total, 6 items) | 3.51 | 1.062 | 1.128 | −0.386 | −0.721 |

| UBP Customers (total, 3 items) | 3.34 | 1.353 | 1.830 | −0.353 | −1.171 |

| UBP Competitors (total, 4 items) | 3.29 | 1.200 | 1.441 | −0.410 | −0.806 |

| UBP Employees (total, 7 items) | 2.60 | 1.232 | 1.517 | 0.344 | −1.013 |

| UBP State/society (total, 6 items) | 2.95 | 1.382 | 1.910 | −0.63 | −1.357 |

| UBPbuspart1_Non-payment | 3.95 | 1.339 | 1.794 | −0.903 | −0.711 |

| UBPbuspart2_Non-compliance with contracts | 3.70 | 1.365 | 1.863 | −0.568 | −1.187 |

| UBPbuspart3_Corrupt behavior of business partner | 3.11 | 1.421 | 2.018 | 0.08 | −1.371 |

| UBPbuspart4_Abuse of the position of large comp. against small | 3.79 | 1.313 | 1.724 | −0.817 | −0.599 |

| UBPbuspart5_Nepotism in the business environment | 3.58 | 1.333 | 1.777 | −0.543 | −0.969 |

| UBPbuspart6_Purposeful bankruptcy | 2.92 | 1.449 | 2.100 | 0.126 | −1.303 |

| UBPcust1_Sale of poor-quality products or services | 3.25 | 1.443 | 2.082 | −0.200 | −1.397 |

| UBPcust2_Avoiding liability for complaints and errors | 3.34 | 1.420 | 2.016 | −0.359 | −1.278 |

| UBPcust3_Misleading advertising, deception | 3.43 | 1.472 | 2.166 | −0.423 | −1.292 |

| UBPcompet1_Abuse of a strong market position, cartel agreements | 3.59 | 1.372 | 1.882 | −0.630 | −0.884 |

| UBPcompet2_Unfair procurement practices | 3.52 | 1.393 | 1.940 | −0.514 | −1.012 |

| UBPcompet3_Patent abuse, theft of ideas/brands | 2.92 | 1.331 | 1.771 | 0.69 | −1.047 |

| UBPcompet4_Purposeful damaging of competitors’ reputation | 3.12 | 1.380 | 1.906 | −0.139 | −1.219 |

| UBPempl1_Employee discrimination | 2.64 | 1.366 | 1.866 | 0.389 | −1.093 |

| UBPempl2_Unlawful wage-paying practices | 2.76 | 1.530 | 2.339 | 0.176 | −1.496 |

| UBPempl3_Failure to comply with employee levies-related obligations | 2.48 | 1.494 | 2.231 | 0.493 | −1.241 |

| UBPempl4_Failure to respect employees’ privacy at the workplace | 2.55 | 1.403 | 1.968 | 0.421 | −1.162 |

| UBPempl5_Unethical behavior towards employees (indecent, unfair, arrogant) | 2.75 | 1.448 | 2.096 | 0.227 | −1.352 |

| UBPempl6_Bad work conditions | 2.56 | 1.398 | 1.956 | 0.446 | −1.122 |

| UBPempl7_Persecution of whistle-blowers | 2.43 | 1.362 | 1.854 | 0.483 | −0.954 |

| UBPstate1_Failure to comply with appl. Laws | 2.86 | 1.474 | 2.172 | 0.125 | −1.414 |

| UBPstate2_Non-payment of taxes, tax fraud | 2.78 | 1.558 | 2.428 | 0.159 | −1.520 |

| UBPstate3_Corruption of civil servants | 2.90 | 1.523 | 2.318 | 0.24 | −1.465 |

| UBPstate4_Misuse of contacts with politicians and officials | 3.13 | 1.532 | 2.346 | −0.221 | −1.438 |

| UBPstate5_Unfair practices in obtaining public contracts, public/euro funds | 3.13 | 1.564 | 2.448 | −0.203 | −1.478 |

| UBPstate6_Environmental damages | 2.91 | 1.454 | 2.114 | 0.44 | −1.349 |

| UBP Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. UBP Bus. Partners | 0.601 ** | |||||||||

| 2. UBP Customers | 0.642 ** | 0.483 ** | ||||||||

| 3. UBP Competitors | 0.689 ** | 0.539 ** | 0.593 ** | |||||||

| 4. UBP Employees | 0.708 ** | 0.384 ** | 0.476 ** | 0.480 ** | ||||||

| 5. UBP State/Society | 0.742 ** | 0.420 ** | 0.496 ** | 0.550 ** | 0.623 ** | |||||

| 6. Industry Sector | 0.046 * | 0.14 | 0.074 ** | 0.052 * | 0.31 | 0.044 * | ||||

| 7. Membership in PNs | −0.122 ** | −0.085 ** | −0.124 ** | −0.133 ** | −0.104 ** | −0.105 ** | −0.13 | |||

| 8. Ownership | −0.09 | −0.46 | 0.22 | −0.35 | 0.25 | −0.05 | 0.171 ** | 0.088 ** | ||

| 9. Company Age | −0.065 ** | −0.048 * | −0.057 ** | −0.047 * | −0.067 ** | −0.053 * | −0.072 ** | 0.245 ** | 0.225 ** |

| Variables | UBP Bus.Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society | UBP Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Sector | Construction | 3.8600 | 3.7067 | 3.6100 | 2.6720 | 3.0653 | 3.3006 |

| Finance | 3.5074 | 3.4815 | 3.3722 | 2.8381 | 2.9815 | 3.1821 | |

| Membership in PNs | Yes | 3.3989 | 3.1423 | 3.1210 | 2.3995 | 2.7701 | 2.9124 |

| No | 3.6098 | 3.5247 | 3.4788 | 2.7212 | 3.1220 | 3.2280 | |

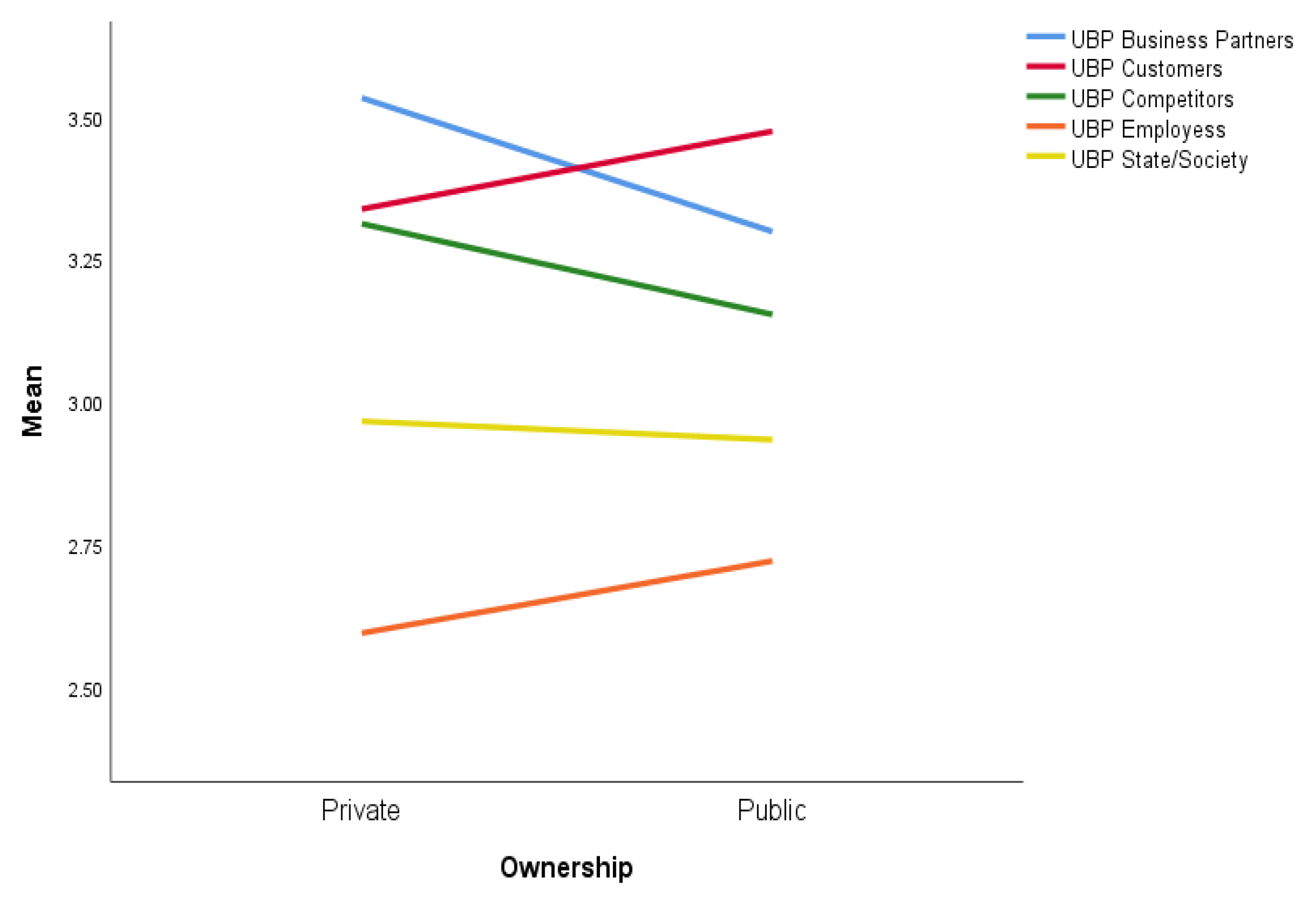

| Ownership | Private | 3.5326 | 3.3377 | 3.3118 | 2.5941 | 2.9656 | 3.0926 |

| Public | 3.2981 | 3.4741 | 3.1528 | 2.7206 | 2.9333 | 3.0564 | |

| Company Age | 0–3 years | 3.7101 | 3.9565 | 3.7174 | 3.5031 | 3.5507 | 3.6472 |

| 4–10 years | 3.5866 | 3.4673 | 3.3480 | 2.6905 | 3.0523 | 3.1716 | |

| 11–15 years | 3.4928 | 3.3399 | 3.2265 | 2.6168 | 2.9144 | 3.0649 | |

| 16–20 years | 3.5340 | 3.3106 | 3.3534 | 2.6986 | 3.0812 | 3.1510 | |

| 21–30 years | 3.5677 | 3.3766 | 3.3898 | 2.5326 | 2.9606 | 3.0995 | |

| 30+ years | 3.2696 | 3.0663 | 2.9673 | 2.4009 | 2.6789 | 2.8294 | |

| Comp. Size | Company Age | UBP Bus.Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society | UBP Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | 0–3 years | 3.9556 | 4.0222 | 3.8667 | 3.6286 | 3.4556 | 3.7462 |

| 4–10 years | 3.6445 | 3.6077 | 3.5177 | 2.7788 | 3.2507 | 3.2968 | |

| 11–15 years | 3.6767 | 3.7028 | 3.5090 | 2.8279 | 3.1044 | 3.2933 | |

| 16–20 years | 3.8661 | 3.6831 | 3.7090 | 2.9930 | 3.5191 | 3.5057 | |

| 21–30 years | 3.6048 | 3.6381 | 3.6357 | 2.5571 | 3.2333 | 3.2456 | |

| 30+ years | 3.8889 | 3.2222 | 3.8333 | 3.0000 | 2.6667 | 3.2821 | |

| Small | 0–3 years | 3.8333 | 4.3333 | 4.7500 | 2.2857 | 4.3333 | 3.7308 |

| 4–10 years | 3.4689 | 3.2881 | 3.1059 | 2.5351 | 2.7401 | 2.9726 | |

| 11–15 years | 3.7207 | 3.3198 | 3.4966 | 2.6911 | 3.2185 | 3.2469 | |

| 16–20 years | 3.5222 | 3.2556 | 3.3667 | 2.5619 | 3.0083 | 3.0904 | |

| 21–30 years | 3.5847 | 3.3825 | 3.4631 | 2.4489 | 2.9208 | 3.0836 | |

| 30+ years | 3.6944 | 3.3704 | 3.1875 | 2.2698 | 2.7407 | 2.9754 | |

| Medium | 0–3 years | 2.8333 | 3.8889 | 3.0833 | 4.0476 | 4.2778 | 3.6538 |

| 4–10 years | 3.5833 | 3.4583 | 3.2500 | 2.6786 | 2.8958 | 3.1154 | |

| 11–15 years | 3.5058 | 3.3158 | 3.1667 | 2.6566 | 2.8889 | 3.0607 | |

| 16–20 years | 3.4667 | 3.3167 | 3.2563 | 2.8179 | 3.0708 | 3.1510 | |

| 21–30 years | 3.6059 | 3.3240 | 3.2897 | 2.6048 | 2.9361 | 3.1006 | |

| 30+ years | 3.1111 | 3.0212 | 2.9603 | 2.4331 | 2.5608 | 2.7680 | |

| Large | 0–3 years | 3.4167 | 3.6667 | 3.3750 | 2.9286 | 3.1667 | 3.2500 |

| 4–10 years | 3.6458 | 2.8333 | 3.0313 | 2.6250 | 3.0208 | 3.0385 | |

| 11–15 years | 2.6911 | 2.6748 | 2.2500 | 2.0000 | 2.0163 | 2.2795 | |

| 16–20 years | 2.9722 | 2.6556 | 2.7333 | 2.2143 | 2.3500 | 2.5513 | |

| 21–30 years | 3.4296 | 3.1831 | 3.1092 | 2.6157 | 2.8310 | 2.9946 | |

| 30+ years | 3.1891 | 2.9700 | 2.8539 | 2.4109 | 2.7378 | 2.7986 |

References

- SCC. Perception of Business Ethics in Slovakia; Slovak Compliance Circle Survey. 2015. Available online: http://www.slovakcompliancecircle.sk/public/media/0414/038-15-siemp-scc-survey-brozura-210x210-en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Remišová, A.; Lašáková, A.; Bohinská, A. Reasons of unethical business practices in Slovakia: The perspective of non-governmental organizations´ representatives. Acta Univ. Agric. Et Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2019, 67, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lašáková, A.; Remišová, A.; Bohinská, A. Barriers to ethical business in Slovakia: An exploratory study based on insights of top representatives of business and employer organizations. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2021. in print. [Google Scholar]

- Baláž, V. Politická ekonómia slovenského kapitalizmu: Inštitucionálna perspektíva. Politická Ekon. 2006, 54, 610–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heugens, P.P.; Lander, M.W. Structure! Agency! (and other quarrels): A meta-analysis of institutional theories of organization. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Liedekerke, L.; Dubbink, W. Twenty years of European business ethics—Past developments and future concerns. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Gllbert, D.R. Business, ethics and society: A critical agenda. Bus. Soc. 1992, 31, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.K.; Agle, B.R.; Wood, D.J. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 853–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, L.S.; Freeman, R.E. Stakeholder theory, fact/value dichotomy, and the normative core: How Wall Street stops the ethics conversation. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderle, G. Towards business ethics as an academic discipline. Bus. Ethics Q. 1996, 6, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderle, G. In search of a common ethical ground: Corporate environmental responsibility from the perspective of Christian environmental stewardship. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, K.E. Business ethics. In Encyclopedia of Ethics; Becker, L., Becker, C., Eds.; Garland Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Castater, N.M. Privatization as a means to societal transformation: An empirical study of privatization in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Nota Di Lav. 2002, 76, 1–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Filatotchev, I.; Starkey, K.; Wright, M. The ethical challenge of management of buy-outs as a form of uropazingn in Central and Eastern Europe. J. Bus. Ethics 1994, 13, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C. In search of owners: Privatization and corporate governance in transition economies. World Bank Res. Obs. 1996, 11, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myant, M.; Drahokoupil, J. International integration, varieties of capitalism and resilience to crisis in transition economies. Eur. Asia Stud. 2012, 64, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J. Transformation and crisis in Central and Eastern Europe: A combined and uneven development perspective. Cap. Cl. 2014, 38, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zakaria, P. Is corruption an enemy of civil society? The case of Central and Eastern Europe. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 34, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y. SMEs and the fallacy of uropazing CSR. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Carrasco, R.; López-Pérez, M.E. Small & medium-sized enterprises and corporate social responsibility: A systematic review of the literature. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 3205–3218. [Google Scholar]

- Von Weltzien Hoivik, H.; Melé, D. Can an SME become a global corporate citizen? Evidence from a case study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Bowd, R.; Tench, R. Corporate irresponsibility and corporate social responsibility: Competing realities. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, K. Mission impossible?: Adopting a CSR-based business model for extractive industries in developing countries. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, J. Formalization of Ethics: The Issue of Standardization. HAL Archives 2005. Available online: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00196424 (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Cooper, R.W.; Dorfman, M.S. Business and professional ethics in transitional economies and beyond: Considerations for the insurance industries of Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, A.; Thibodeaux, M.S. Institutionalization of ethics: The perspective of managers. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 22, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka, W.; Szántó, R. Corporate social responsibility and business ethics in controversial sectors: Analysis of research results. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2018, 14, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lähdesmäki, M. Construction of owner-manager identity in corporate social responsibility discourse. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2012, 21, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goliaš, P. Regionálne Rozdiely v SR—Prehľad Dôležitých Štatistík; INEKO—Inštitút pre Ekonomické a Sociálne Reform: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- PAS. Korupcia je na Slovensku Bežná a Rastie, Osobnú Skúsenosť s Ňou Majú tri Štvrtiny Podnikateľov. Available online: https://www.alianciapas.sk/2017/12/21/korupcia-je-na-slovensku-bezna-a-rastie-osobnu-skusenost-s-nou-maju-tri-stvrtiny-podnikatelov/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Transparency International. Corruption Perception Index. 2019. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2019/results (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meyer, J.W. Reflections on institutional theories of organizations. In The Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism. In Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; Greenwood, R., Oliver, C., Sahlin, K., Suddaby, R., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 788–809. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker, L.G. Institutional theories of organization. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1987, 13, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beschorner, T.; Hajduk, T. Responsible practices are culturally embedded: Theoretical considerations on industry-specific corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fassin, Y. The reasons behind non-ethical behaviour in business and entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 6, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vee, C.; Skitmore, R.M. Professional ethics in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2003, 10, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowen, P.; Pearl, R.; Akintoye, A. Professional ethics in the South African construction industry. Build. Res. Inf. 2007, 35, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Rahman, H.; Wang, C.; Yap, X.W. How professional ethics impact construction quality: Perception and evidence in a fast developing economy. Sci. Res. Essays 2010, 5, 3742–3749. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, J.P. Banking ethics and the Goldman rule. J. Econ. Issues 2011, XLV, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, C.; Lefcovitch, A. Corporate social responsibility and banks. Amic. Curiae 2009, 78, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohn, A.; Fehr, E.; Maréchal, M.A. Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature 2014, 51, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.W. The adolescence of institutional theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1987, 32, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, A. Professional associations as communities of practice: Exploring the boundaries of ethics and compliance and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2017, 122, 359–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G.; Wood, G.; Callaghan, M. A comparison of business ethics commitment in private and public sector organizations in Sweden. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2010, 19, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmer, D.; Coursey, D. Ethical work climates: Comparing top managers in public and private organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1996, 6, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G.A. Public and private management: What’s the difference? J. Manag. Stud. 2002, 39, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Schindehutte, M.; Walton, J.; Allen, J. The ethical context of entrepreneurship: Proposing and testing a developmental framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 40, 331–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannafey, F.T. Entrepreneurship and ethics: A literature review. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belak, J.; Mulej, M. Enterprise ethical climate changes over life cycle stages. Kybernetes 2009, 38, 1377–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohatá, M. Business ethics in Central and Eastern Europe with special focus on the Czech Republic. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 15, 1571–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remišová, A.; Lašáková, A.; Kirchmayer, Z. Influence of formal ethics program components on managerial ethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanovičová, D.; Vašáková, L. Corruption as a global problem. In Proceedings of the 17th International Scientific Conference on Globalization and Its Socio-economic Consequences, Žilina, Slovakia, 4–5 October 2017; pp. 3069–3075. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac, O.; Davidovic, M.; Mijatovic, M.D. Legal framework, political environment and economic freedom in central and Eastern Europe: Do they matter for economic growth? Post-Communist Econ. 2020. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Special Eurobarometer 470. European Union Report on Corruption; Directorate-General for Communication: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Cremer, D.; Vandekerckhove, W. Managing unethical behavior in organizations: The need for a behavioral business ethics approach. J. Manag. Organ. 2017, 23, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, R.E.; Martin, K.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder capitalism. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remišová, A.; Lašáková, A. Theoretical foundations of the Bratislava school of business ethics. Ethics Bioeth. 2017, 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nicholson, N.; Robertson, D.C. The ethical issue emphasis of companies: Content, patterning, and influences. Hum. Relat. 1996, 49, 1367–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, A. A typology of moral problems in business: A framework for ethical management. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasthuizen, K.; Huberts, L.; Heres, L. How to measure integrity violations. Public Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, N.; Colvin, C.; Wong, Y.-Y. Navigating corporate social responsibility components and strategic options: The IHR perspective. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, M.; Denkers, A.; Huisman, W. Rule violations by SMEs: The influence of conduct within the industry, company culture and personal motives. Eur. J. Criminol. 2020, 17, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belas, J.; Cipovova, E.; Klimek, P. The loyal and moral principles in the sale of bank products. A case study from Slovak republic. Int. J. Math. Models Methods Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Besser, T.L.; Miller, N. The structural, social, and strategic factors associated with successful business networks. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondruš, M. Svet Podnikateľských a Zamestnávateľských Organizácií na Slovensku. Available online: https://www.podnikajte.sk/manazment-marketing/c/2560/category/manazment-a-strategia/article/podnikatelske-organizacie.xhtml (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Kirchmayer, Z.; Remišová, A.; Lašáková, A. The perception of ethical leadership in the public and private sectors in Slovakia. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2019, 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lašáková, A.; Bajzíková, Ľ.; Blahunková, I. Values oriented leadership—Conceptualization and preliminary results in Slovakia. Bus. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hoogh, A.H.B.; Den Hartog, D.N. Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, M.S.; Aydemir, M. Ethical leadership and employee behaviours: An empirical study of mediating factors. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2014, 9, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Wright, B.E.; Yukl, G. Does ethical leadership matter in government? Effects on organizational commitment, absenteeism, and willingness to report ethical problems. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 74, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lail, B.; MacGregor, J.; Stuebs, M.; Thomasson, T. The influence of regulatory approach on tone at the top. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Commission Recommendation no. 2003/361/EC of 6 May 2003 Concerning the Definition of Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. 2003. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003H0361&from=EN (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- EP. Regulation (EC) No 1059/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 May 2003 on the Establishment of a Common Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS). 2003. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32003R1059&from=EN (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Stankovičová, I.; Frankovič, B. Určenie veľkosti vzorky pre aplikovaný výskum. Forum Stat. Slovacum 2020, XVI, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, D.; Cowton, C.J. Method issues in business ethics research: Finding credible answers to questions that matter. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crane, A. Are you ethical? Please tick yes or no. On researching ethics in business organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 20, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Monroe, G.S. Exploring social desirability bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetiniuc, V.; Luchian, I. Banking ethics: Main conceptions and problems. Ann. Univ. Petroşani. Econ. 2014, 14, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gyori, Z. Existing and Potential Solutions to Reduce Financial Exclusion—Theoretical Considerations and Practical Initiatives at the Meeting Point of Finance and Ethics; Corvinus Economics Working Papers (CEWP) 2019/02; Corvinus University of Budapest: Budapest, Hungary, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Holtfreter, K. The effects of corporation- and industry-level strain and opportunity on corporate crime. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2012, 49, 151–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulet, E.; Parnaudeau, M.; Relano, F. Banking with ethics: Strategic moves and structural changes of the banking industry in the aftermath of the subprime mortgage crisis. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A. Responsible care: An assessment. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Van Tulder, R. Child labor and multinational conduct: A comparison of international business and stakeholder codes. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 36, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.C. Industry business associations: Self-interested or socially conscious? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderle, G. Global competition and corporate responsibilities of small and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2004, 13, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomescu, M.; Popescu, M.A. Ethics and conflicts of interest in the public sector. Contemp. Read. Law Soc. Justice 2014, 5, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Nechala, P.; Kormanová, M.; Kubíková, J.; Piško, M. Slovak Companies Owned by Public Sector Remain Non-Transparent; Transparency International Slovensko: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nemec, J. Public administration reforms in Slovakia: Limited outcomes (Why?). Nispacee J. Public Adm. Policy 2018, 11, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinn, R.E.; Cameron, K. Organizational life cycles and shifting criteria of effectiveness: Some preliminary evidence. Manag. Sci. 1983, 29, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belak, J.; Milfelner, B. Exploring enterprise life cycle: Differences in informal and formal institutional measures of business ethics implementation. In Proceedings of the MEB 2010—8th International Conference on Management, Enterprise and Benchmarking, Budapest, Hungary, 4–5 June 2010; pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, H.R.; Robbins, J.E. An empirical investigation of the organizational life cycle model for small business development and survival. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1992, 30, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Retolaza, J.L.; Ruiz, M.; San-Jose, L. CSR in business start-ups: An application method for stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aquila, J.M. Financial accountants’ perceptions of management’s ethical standards. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 31, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, L.K.; Weaver, G.R.; Brown, M.E. It’s lovely at the top: Hierarchical levels, identities, and perceptions of organizational ethics. Bus. Ethics Q. 2008, 18, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construction vs. Other Sectors | UBP Total | UBP Bus. Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society |

| Mann–Whitney U | 62,637.500 | 57,175.000 | 61,306.500 | 59,920.500 | 69,276.000 | 69,351.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 747,672.500 | 742,210.000 | 746,341.500 | 744,955.500 | 754,311.000 | 754,386.000 |

| Z | −2.639 | −4.020 | −2.994 | −3.332 | −0.970 | −0.952 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.332 | 0.341 |

| Finance vs. Other sectors | UBP Total | UBP Bus. Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society |

| Mann–Whitney U | 26,647.500 | 28,042.000 | 26,365.500 | 26,638.000 | 24,825.000 | 27,720.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 808,522.500 | 29,077.000 | 808,240.500 | 808,513.000 | 806,700.000 | 809,595.500 |

| Z | −0.599 | −0.034 | −0.719 | −0.605 | −1.341 | −0.165 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.549 | 0.973 | 0.472 | 0.545 | 0.180 | 0.869 |

| UBP Total | UBP Bus. Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney U | 137,960.000 | 147,332.500 | 138,932.500 | 136,398.500 | 142,924.000 | 142,776.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 266,231.000 | 275,603.500 | 267,203.500 | 264,669.500 | 271,195.000 | 271,047.500 |

| Z | −5.093 | −3.454 | −4.957 | −5.382 | −4.228 | −4.258 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| UBP Total | UBP Bus. Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann–Whitney U | 50,605.000 | 45,569.500 | 48,917.000 | 47,055.500 | 48,436.000 | 51,108.500 |

| Wilcoxon W | 54,700.000 | 49,664.500 | 713,045.000 | 51,150.500 | 712,564.000 | 55,203.500 |

| Z | −0.377 | −1.917 | −0.898 | −1.464 | −1.040 | −0.224 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.706 | 0.055 | 0.369 | 0.143 | 0.298 | 0.823 |

| UBP Total | UBP Bus. Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square | 20.970 | 12.721 | 13.678 | 21.535 | 20.558 | 14.301 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| UBP Total | UBP Bus. Partners | UBP Customers | UBP Competitors | UBP Employees | UBP State/Society | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | Chi-Square | 4.193 | 2.165 | 2.373 | 10.202 | 3.423 | 4.623 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.522 | 0.826 | 0.795 | 0.070 | 0.635 | 0.464 | |

| Small | Chi-Square | 3.017 | 0.934 | 7.004 | 3.856 | 6.283 | 3.675 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.697 | 0.968 | 0.220 | 0.570 | 0.280 | 0.597 | |

| Medium | Chi-Square | 11.111 | 3.447 | 3.664 | 7.168 | 7.702 | 7.131 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.049 | 0.631 | 0.599 | 0.208 | 0.173 | 0.211 | |

| Large | Chi-Square | 16.010 | 6.451 | 14.707 | 10.617 | 14.902 | 15.363 |

| Asymp. Sig. | 0.007 | 0.265 | 0.012 | 0.060 | 0.011 | 0.009 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lašáková, A.; Remišová, A.; Bajzíková, Ľ. Differences in Occurrence of Unethical Business Practices in a Post-Transitional Country in the CEE Region: The Case of Slovakia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063412

Lašáková A, Remišová A, Bajzíková Ľ. Differences in Occurrence of Unethical Business Practices in a Post-Transitional Country in the CEE Region: The Case of Slovakia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063412

Chicago/Turabian StyleLašáková, Anna, Anna Remišová, and Ľubica Bajzíková. 2021. "Differences in Occurrence of Unethical Business Practices in a Post-Transitional Country in the CEE Region: The Case of Slovakia" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063412

APA StyleLašáková, A., Remišová, A., & Bajzíková, Ľ. (2021). Differences in Occurrence of Unethical Business Practices in a Post-Transitional Country in the CEE Region: The Case of Slovakia. Sustainability, 13(6), 3412. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063412