Abstract

Central Asian states, where freshwater is a strategic resource, are oriented towards regional conflict rather than cooperation. First, the article analyses the role of the unequal distribution of freshwater that has been generating conflicts in Central Asia in the post-Soviet period. Next, these conflicts are examined. Finally, we provide some recommendations on the non-conflictual use of water.

1. Introduction

Freshwater is a strategic natural resource in any region of the world, and this is especially true for the Central Asian region, which currently comprises five former constituent republics of the Soviet Union: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Nevertheless, it is fossil fuels—principally, oil and natural gas—that have always been exposed to scientific scrutiny in the post-Soviet states [1,2,3,4]. In order to compensate the scarcity of scientific literature on the issue, this paper analyses the role of freshwater as a natural resource that has been generating conflicts in Central Asia since the collapse of the Soviet Union as well as the conflicts themselves.

In Central Asia, the relations between the five states are not oriented towards cooperation but towards conflict. For example, when the Soviet Union collapsed, new independent states began to emerge, failing to define their territorial borders properly. Thus, regarding the lack of clear borders, all along the interstate frontiers there are territories which have no strict demarcation. It is considered highly problematic to set a boundary through multiethnic villages. Nationalities were never confined to their official borders having relatives and doing business technically “abroad”. Therefore, we face a phenomenon of compact residence and a large number of enclaves.

The lack of regional cooperation and the governments’ weakness and negligence normally result into negotiations coming to deadlock. The governments tend to take into consideration only national interests and are reluctant to make concessions.

In the field of water management the existing legislation is inefficient. The disintegration of the regional joint water and power systems, previously managed by the Soviet government, led to an urgent need for new legislation which would define the use of power and water facilities, at that time owned by five independent states. However, the principles of transboundary water resources management elaborated in 1992 were not efficient enough. Neither were the additional documents, which intended to meet the demands of those countries that claimed that the 1992 agreement favoured one country and neglected the interests of the others [5].

It is worth mentioning that the concept “freshwater”—or just “water”—includes water systems and any of their elements. Further, we restrict our study to freshwater only. Therefore, the paper does not cover issues connected to the Caspian Sea or the disappearing Aral Sea (however, logically, it will be necessary to make some references to them); in this sense, the paper will also have environmental destruction and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG, in particular the Indicator 6.5.2 “Proportion of transboundary basin area with an operational arrangement for water cooperation”) as a backdrop. Global warming would increase the demand for water, especially in the states threatened by desertification, which inevitably exacerbates tensions between Central Asian countries.

First of all, we will put our research into a qualitative analytical framework, debate, and the wider context of the published literature on water conflicts. The hydropolitics literature has several schools of thought, including water wars [6,7,8]; a more legal school of conflict and hydrodiplomacy [9,10,11]; or hydro-hegemony [12,13]. There is also a literature in the vein of Peter Haas’ work on the Mediterranean Blue Plan (1989) assuming that better science (joint fact finding) will lead the way out; the work of Dukhovny and De Schutter (2011) is an example of this [14,15]. Additionally, to better contextualize the document within the relevant literature on hydropolitics, regarding the definition of cooperation around water and conflicts over water, it is also necessary to mention the work of Mirumachi and Zeitoun in particular [16] and the work of the London Water Research Group on critical hydropolitics, including publications on water infrastructure [17,18,19,20,21,22] and the work of Ahmet Conker on “small is beautiful but not trendy” in which he explains how governments use different strategies to build dams, generating transboundary conflicts [23].

Water wars are believed to be the final step of conflicts doomed to remain unresolved by peaceful means. In the context of constant population growth, water scarcity is getting more and more widespread, which cannot but raise extreme concern among politicians. While they deem water as the principal motivation for military movements and territorial claims, the populations of the most arid and water-deprived areas live under the threat of a war which may break out over the precious resource at any time. This article speaks closely to the literature of the politics of scarcity and crisis, and on how such issues are constructed. Water scarcity is a key concept for the paper; it is linked to water crisis, water shortage and water stress. A discussion of the construction of water scarcity (discourses of water scarcity) can be found in the works of Mehta, Edwards, Allouche, and Hussein [18,19,24,25,26].

Currently, global geopolitical interests determine the management of natural resources. A hydro-diplomatic negotiation at various levels, from the local to the international one, makes possible the balance between the two spheres. This model is a powerful instrument on the way to rational water use, marine and terrestrial ecosystem preservation and restoration, wastewater collection, treatment, storage and its possible future reuse. Hydro-diplomacy is a more effective alternative to a conflictive behaviour. Throughout history, we have had the evidence not only of water’s conflict-generating capacity but also of its ability to encourage cooperation and establish a dialogue between the rivalries.

Joint fact finding is sometimes considered to be the most important element of water diplomacy. It is a multi-stage collaborative process that makes negotiating parts with different interests and perspectives work together on finding an efficient and durable solution.

“Hydro-hegemony is hegemony at the river basin level, achieved through water resource control strategies such as resource capture, integration and containment” [12]. These strategies can possibly be applied due to the power asymmetries that exist between neighbouring nations. Therefore, the outcome of the struggle for water is predicated on the form of hydro-hegemony; usually, it favours the most powerful actor.

First, the article analyses the role of the unequal distribution of freshwater that has been generating conflicts in Central Asia in the post-Soviet period. Next, these conflicts are examined. Finally, we provide some recommendations on the non-conflictual use of water.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology used is eminently qualitative-interpretive. The main method is the review, identification and analysis of the specific scientific literature whose theoretical and empirical contributions are more relevant to the subject in question. As will be seen, the information collected from secondary sources has been fundamental, which have allowed us to access the knowledge accumulated by reputable academic and intellectual specialists in books, book chapters, articles, interviews, and compilations and documentary analysis of specialized journals and newspapers (Central Asian and international). All the legal norms have been extracted from the corresponding official gazettes.

The Pacific Institute complies in its Water Conflict Chronology [27], which is regularly updated and reviewed, 926 conflicts concerning freshwater that erupted over five thousand years worldwide, from 3000 BC to 2019, inclusive. Though there is no record or historical evidence of many of the conflicts, this is one of the most complete chronologies, especially if we speak about the 20th and 21st centuries, which this article is focused on; covering the conflicts that occurred in Central Asia from 1990 to 2019. The President Emeritus of the Pacific Institute is precisely the mentioned Peter Gleick, one of the world’s leading authorities on the matter, so we are going to frame our article and our research question in the school of thought of the water wars within the hydropolitical literature.

Peter Gleick’s Pacific Institute chronology, which is the basis for our work, classifies these conflicts as conflicts over water. In this sense, it is very important to underline from the beginning that the article does not intend to weigh the importance of other possible shared causes of some conflicts, but rather to analyze and highlight the role of water itself from a qualitative point of view.

The first conflict listed in this chronology was of a divine nature and took place in the region known today as the Middle East in 3000 BC, when, according to an ancient Sumerian legend, the deity Ea used water as a weapon and punished people for their sinful life with a six-day storm. The legend alludes to the Genesis flood narrative found in the Tanakh and Noah’s Ark [27,28]. The last conflict included in the chronology occurred in Ukraine in 2019, when a shrapnel damaged a pipeline in the Siverski Donetsk-Donbass channel near the city of Horlivka, which deprived more than three million local people on both sides of the conflict of sufficient or any water [27,29].

According to the classification system of the Pacific Institute [27], there are three categories of conflicts that are based on the role of water played in them.

Trigger: Water as a trigger or root cause of conflict, where there is a dispute over the control of water or water systems or where economic or physical access to water, or scarcity of water, triggers violence.

Weapon: Water as a weapon of conflict, where water resources, or water systems themselves, are used as a tool or weapon in a violent conflict.

Casualty: Water resources or water systems as a casualty of conflict, where water resources, or water systems, are intentional or incidental casualties or targets of violence.

In this paper, we are going to tackle all the three categories. Of the above-mentioned 926 conflicts listed by the Pacific Institute, in 316 of them, freshwater took on the role of a trigger (in whole or in part); in 173 conflicts they were used as a weapon (in whole or in part); and, finally, in 505 cases we would refer to them as casualty (in whole or in part).

Although Central Asia comprises only five states, the region was the scene of twenty conflicts over thirty years, namely from 1990 to 2019. The study of conflict potential started in 1990; in 1991, the Soviet Union collapsed and new independent states began to emerge. Consequently, we have decided not to cover the pre-1990 water conflicts in this paper; however, we will make reference to them in some cases, such as to explain the origins or background of the conflicts that occurred between 1990 and 2019 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Conflicts where water played different roles in Central Asian countries (adapted from [27]).

How do we define conflict? In accordance with the Pacific Institute [27], an incident is listed as a conflict when there is violence (injuries or deaths) or threats of violence (including verbal threats, military maneuvers, and shows of force). We do not include instances of unintentional or incidental adverse impacts on populations or communities that occur associated with water management decisions, such as populations displaced by dam construction or impacts of extreme events such as flooding or droughts.

Thus far, the conflicts we are going to cover in the paper have not been studied enough. They are conflicts over a scarce resource such as water. Our idea is that these conflicts are to be studied, in the first place, per se and independently. Actually, as the result of that commonly accepted scientific approach, the actual and potential capacity for destabilisation contained in conflicts of this kind has not been analysed profoundly either.

Although there is scientific literature on conflicts in Central Asia, including conflicts over natural resources—particularly, water—and despite the fact that there have been a significant number of them in two decades, two areas for improvement have been detected in the literature.

Firstly, there is no direct, specific and clear connection between conflicts, on the one hand, and water, on the other hand. Secondly, a comprehensive and structured exposition and analysis of the origin and evolution of these conflicts has not been accomplished. This article attempts to deal with these deficiencies.

As we have already indicated, it is very important to underline that the article does not intend to weigh the importance of other possible shared causes of some conflicts, but rather to analyze and highlight the role of water itself from a qualitative point of view (therefore without using statistical analysis or similar).

Furthermore, Peter Gleick’s Pacific Institute chronology, which is the basis for our work, classifies these conflicts exactly as conflicts over water.

The research question, framed in the school of thought of the water wars within the hydropolitical literature, is: what was, in qualitative terms, the real capacity for the direct and indirect generation of conflicts of water as a natural resource with great strategic value due to the unequal distribution of water in a region like Central Asia, whose states are not oriented towards cooperation but towards conflict, in the period of 1990 to 2019?

The hypothesis of this study, theoretically informed, which answers this research question, is: in the years 1990 to 2019, in a regional context such as Central Asia, where the relations between the five states are not oriented towards cooperation but towards conflict, the unequal regional distribution of water has made it a natural resource with great strategic value and that in qualitative terms has had a very high real capacity for the direct and indirect generation of conflicts.

- Water Resources in Central Asia

Central Asia covers an area of more than 4 million km2, and 70 percent of this vast territory is deserts, semi-deserts and dry steppes [5]. For that reason, the region contains extensive zones of insufficient moistening and soil degradation. Water resources in Central Asia include surface water (rivers and lakes), groundwater, and glaciers. The Tian Shan, the Pamir Mountains, and the Altai Mountains are the major water sources of the region (Table 2).

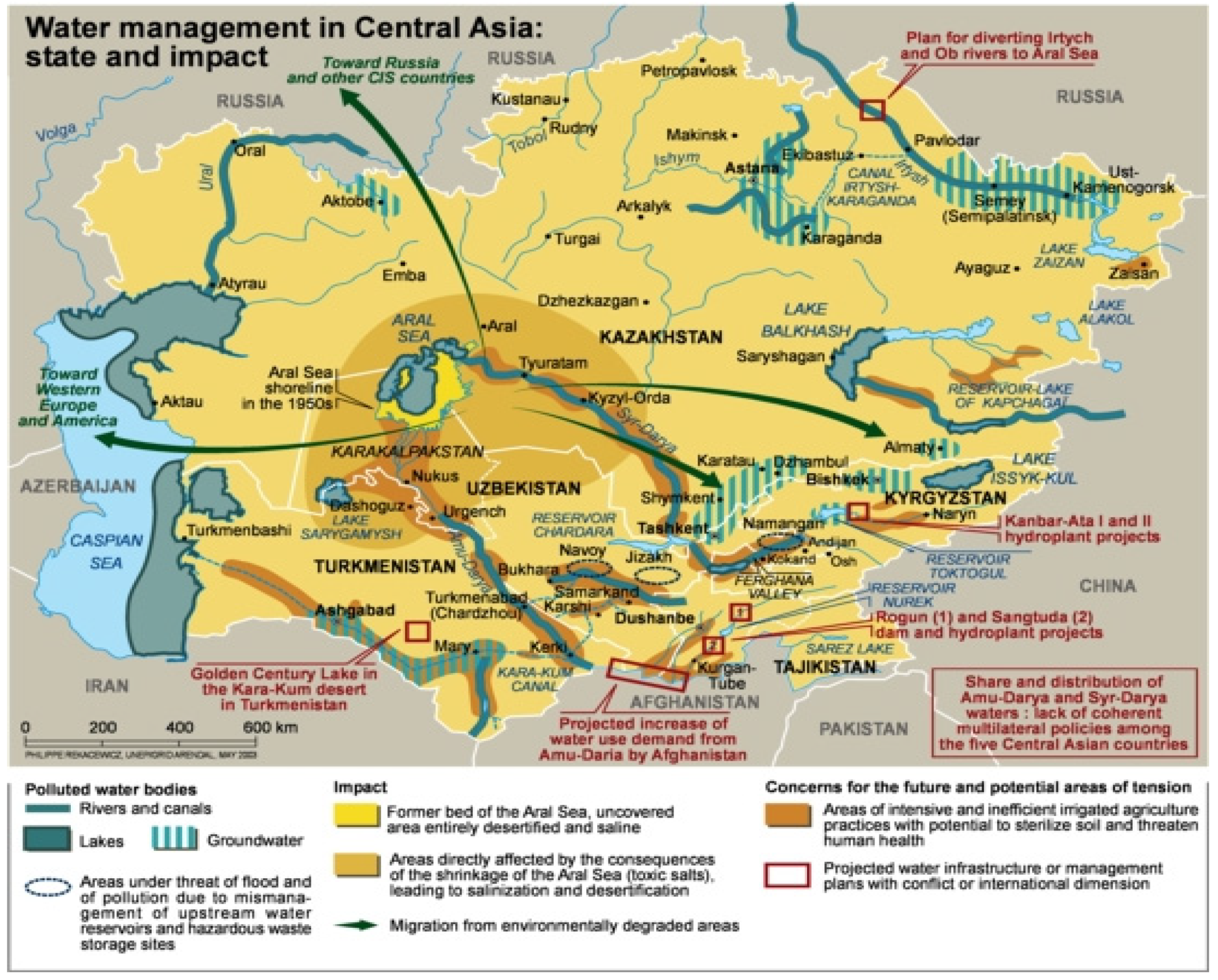

The Aral Sea basin in Central Asia is one of the most ancient centers of civilization. Its two main rivers are the Amu Darya and Syr Darya [30] (p. 16). Firstly, their water flows downstream to arid lands that need irrigation and, secondly, the Syr Darya feeds the North Aral Sea [31]. As for the Aral Sea, once it was the world’s fourth-largest lake, after the Caspian Sea, and Lakes Superior and Victoria but, by 2015, hardly 10% of it was left [32]. The Amu Darya and Syr Darya, together with their tributaries Vakhsh, Panj, Surkhandarya, Kafirnigan, Zerafshan, Naryn, Chirchiq, Kara Darya and others, form a large water system [31] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Water management in Central Asia: state and impact [33].

- Amu Darya

The Amu Darya extends over 2540 km, and is the longest river in Central Asia. Over centuries, the Amu Darya “has not only been the source of life for vast arid lands but has also served as a border and a line of communication” [34]. The river is formed by the junction of Vakhsh and Panj rivers on the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border and flows west–northwest to the southern shore of the Aral Sea.

In the middle reach, four large tributaries flow into the Amu Darya. They are the Surkhan Darya and Sherabad rivers (right tributaries), and the Kunduz and Kokcha rivers (left tributaries). In its upper reaches, the Amu Darya partly serves as Afghanistan’s natural border with Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. In its lower course, the Amu Darya forms part of the Uzbekistan–Turkmenistan border.

- Syr Darya

The Syr Darya’s length is 2256 km. It originates in the Tian Shan Mountains (Kyrgyzstan and eastern Uzbekistan) where the Naryn River merges with the Kara Darya. Then, it flows west and north-west through Uzbekistan and the southern region of Kazakhstan towards the North Aral Sea. Thus, the Syr Darya Basin is divided among four Central Asian countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Its major tributaries are The Chirchiq, The Keles, and The Angren.

- Distribution of Freshwater Resources

Table 2.

Distribution of Freshwater Resources in Central Asian Countries (adapted from [35]).

Table 2.

Distribution of Freshwater Resources in Central Asian Countries (adapted from [35]).

| Country | Total Area, km2 | Water Area, km2 | The Longest Rivers | The Length Along the Territory of the State, km | The Largest Lakes | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | 2,724,900 | 25,200 | Ertis | 1700 | Caspian Sea | 0.4 mln (total area) |

| Esil | 1400 | Aral Sea | 46.64 | |||

| Syr Darya | 1400 | Alakol | 2.6 | |||

| Oral | 1082 | Teniz | 1.6 | |||

| Kyrgyzstan | 199,951 | 8150 | Naryn | 535 | Issyk-Kul | 6.2 |

| Chu | 221 | |||||

| Kizil-Suu | 210 | Sonkul | 0.3 | |||

| Talas | 210 | |||||

| Chatkal | 205 | Chatyr-Kul | 0.2 | |||

| Sari-Djaz | 198 | |||||

| Tajikistan | 143,100 | 2590 | Amu Darya-Panj | 921 | Karakul | 380.0 |

| Zaravshan | 877 | Sarez | 79.6 | |||

| Bartang-Murgab-Oksu | 528 | Zorkul | 38.9 | |||

| Vakhsh | 524 | Yashikul | 2.6 | |||

| Kafirnigan | 387 | |||||

| Turkmenistan | 488,100 | 18,170 | About 80% of the territory of the country has no regular surface flow. Rivers are located exclusively in southern and eastern Turkmenistan. | Most lakes are salty. Freshwater lakes are Yaskhan and Topiatan. There are also two more lakes, the Kouata and the Khordjunly, which are found in the mountains. | ||

| Amu Darya | 1415 | |||||

| Tejen | 1150 (total length) | |||||

| Atrek | 669 (total length) | |||||

| Murgab | 530 | |||||

| Uzbekistan | 447,400 | 22,000 | Amu Darya | 1415 | – | – |

| Syr Darya | 2122 (total length) | |||||

| Zeravshan | 877 | |||||

- Water Stress in Central Asian Countries

Central Asia’s economy is mostly centered on irrigated agriculture, including the cultivation of water-intensive crops such as cotton. Overall, around 100,000 km2 of lands need river water irrigation [36]. Therefore, agriculture is the major water consumer in Central Asia, and its water use per capita significantly surpasses that in European countries. As a result, the intensive water use together with the scarcity of water resources put huge stress on the water supply. Water use can be measured by total freshwater withdrawal, as a percentage of total renewable water resources. According to the European Environment Agency’s criteria, a percentage equal to the greater of 20% represents a certain water stress. Thus, all five Central Asian countries are water-stressed, particularly Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan (Table 3).

Table 3.

Water Stress in Central Asian Countries [37].

- Water Infrastructure

Water infrastructure in Central Asia comprises “hundreds of reservoirs, dams, irrigation systems and pumping stations, a lot of channels and tens of multi-purpose waterworks facilities” [38]. Tajik Nurek Dam situated on the Vakhsh River is the world’s highest rockfill dam, and the Karakum Canal in Turkmenistan is one of the longest canals in the world.

There are more than 1200 dams in Central Asia, of which one hundred ten are classified as large dams [38]. Many of them have interstate status as they are found in the transboundary river basins, for example, in the Amu Darya or in the Syr Darya.

Hydraulic facilities serve numerous purposes such as “drinking, industrial and agricultural water supply, irrigation and hydropower, fisheries and navigation, recreation and environmental sustainability” [38].

Currently, waterworks safety is rated as inadequate, while funds allocated to operational activities are still lacking. Judging by the emergency cases that occurred over the recent years, both “timely preventive and overall repair” and efficient staff training are urgently needed to ensure the safe and reliable operation of hydraulic facilities as well as to avoid accidents and emergency situations [38].

- Access to Clean Water in Central Asia

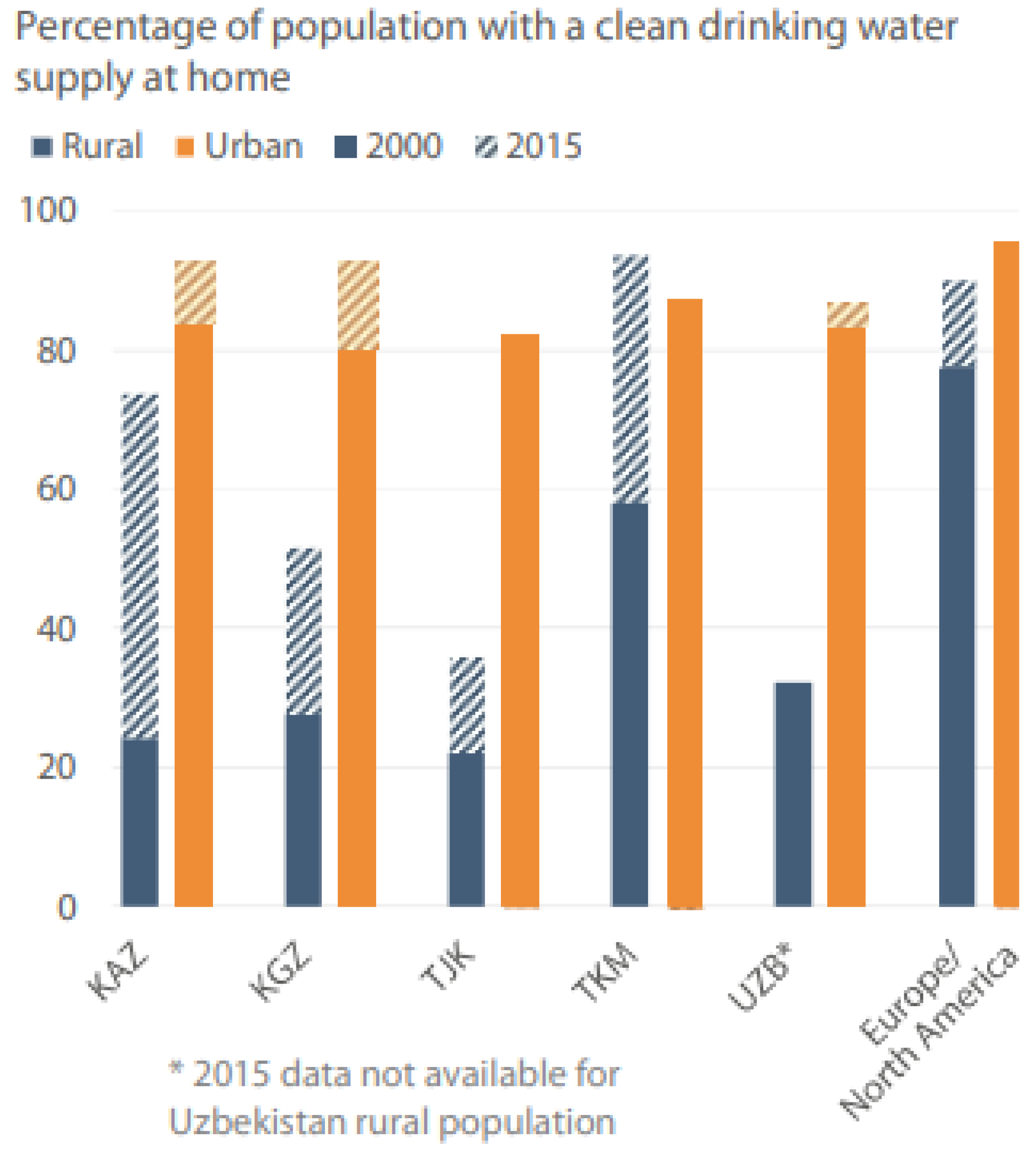

Although domestic water supplies have improved significantly, many people still do not have in-house water services. Mostly, people from rural areas face this problem; however, there are certain districts within the Kyrgyz capital city of Bishkek where it takes locals several hours a day to carry water from nearby pumps. The construction of new water-supply systems and the maintenance of the existing ones demand funds, which are always lacking [36].

It is estimated that for about 22 milion people, or 31% of the total Central Asian population, safe water is hardly accessible [39]. The majority of these water-deprived people are rural inhabitants. They still cover long distances on foot, make use of raw water directly from streams and irrigation canals, or buy water of dubious quality, which is delivered by tanker trucks.

According to Burunciuc [39], in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, only 31% of the rural population can benefit from safely managed water, in comparison with 86% and 57% in urban areas, respectively. The percent of Kyrgyz villagers who had access to safely managed water in 2017 was about 54%, which was a great progress for the country.

As for the sanitation situation in Central Asia, while urban population is provided with basic services, people in rural areas have a very limited access to sewer connections and the use of septic tanks is rarely available either. These inadequate hygienic conditions not only entail environmental contamination but also put public health at risk [39] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of people with a clean drinking water supply at home [36].

- Water Quality in Central Asia

Since the 1960s, due to the development of irrigated agriculture, the fast pace of industrialization, cattle husbandry, urbanization, and the creation of drainage systems, water quality in river basins has irreversibly worsened. This development affected mostly the river lower reaches.

Thus, the main sources of water pollution in Central Asia are agriculture, industry, and municipal wastewater.

In Kazakhstan, water resources are considered to be of poor quality due to “chemical, oil, manufacturing and metallurgical industry contamination” [40]. Moreover, urban constructions, various household wastes, farms, irrigated fields increase the level of pollution as well.

Nevertheless, in Kyrgyzstan, river water is classified as relatively safe as it is fed by glacial melting. Sometimes “the use of fertilizers and chemicals, industrial waste, non-compliance of the sanitary code, improper conditions for sewerage systems”, and livestock farming contribute to the pollution level [40]. However, the serious problem of Kyrgyzstan in terms of water quality is nuclear tailing dumps [40].

In Tajikistan, water quality is good enough, with the exception of several lakes and groundwater sources.

In Turkmenistan, on the contrary, river water and drainage systems are affected by “high concentrations of salts and pesticides both from domestic sources and upstream international basins” [40].

In Uzbekistan, the quality of water is poor in those rivers which are contaminated with sewage and municipal wastewater. Other sources of pollution are petroleum industry, phenols, nitrates, and heavy metals pollution [40].

Taking everything into account, we conclude that the five Central Asian states are facing a precarious water shortage situation. Depleted and degraded transboundary water supplies lead to interstate and intrastate conflicts; thus, we are talking about the high conflict-generating capacity of water in Central Asia.

3. Results

3.1. Conflicts

We will chronologically describe and analyse the conflicts below.

3.1.1. The Osh Riots, Southern Kyrgyzstan (1990)

The Osh riots were ethnic clashes between Kirghiz and Uzbeks that took place in June 1990 in then Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic (Kirghiz SSR) [27,41]. The conflict had its roots in the remote 1920s of the 20th century when the Soviet government divided the fertile Fergana Valley among its three constituent republics: Kirghizia, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. Nevertheless, the three nationalities were never strictly confined to within their official borders. Therefore, Kirghiz territory (especially, its southern regions) was populated by a significant number of Uzbeks who were traditionally involved in commerce and farming [42].

The spring of 1990 saw the rise of national consciousness in both Kirghizia and Uzbekistan. The southwestern Kirghiz city of Osh became the birthplace of two NGOs: Uzbek Adolat (Uzbek for "justice") and Kirghiz Osh Aymaghi (Kirghiz for “the region of Osh”) [42,43].

One of the greatest problems Kirghiz people were facing at that time was land shortage for housing development. Throughout the spring of 1990, the Kirghiz youth, supported by Osh Aymaghi, organized numerous manifestations claiming lands. The local authorities yielded to their demands and agreed to give them 32 hectares of a collective farming where the majority of workers were Uzbeks [43]. The governmental solution was taken as an offence by the whole Uzbek population of the region as the peasants were to be deprived of the scarce furtive land that could be irrigated with enough water to meet the cotton water requirements.

In retaliation, the Uzbeks mounted demonstrations requiring (not for the first time) that the government should grant the autonomy to the territory of their compact residence in the Osh region. The authorities invalidated the recently taken decision. Nevertheless, they did not manage to satisfy the demands of either Uzbeks or Kirghiz. The ethnic tensions were growing [42,43].

On 4 June, 1990 two outraged crowds converged on the opposite sides of a cotton field that had been previously assigned for housing purpose. In the effort to keep the crowds back, the police opened fire on the people, killing (or injuring) several Uzbeks. Both crowds got infuriated and headed for the city of Osh where violent clashes between Uzbeks and Kirghiz erupted. The massacre lasted for several days spreading to other regions [42,43].

There is a range of possible reasons for the bloodshed of 1990. However, Bruce Pannier states in one of his articles that “It was a dispute over water that triggered the 1990 events” [44].

3.1.2. The Tyuyamuyun Reservoir, the Amu Darya River (1992)

In February, 1992 Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan signed the agreement which would determine their future water policy [45] (p. 163). The document stipulated the creation of The Interstate Commission for Water Coordination and its two control bodies, which were Basin Water Organizations “Syrdarya” and “Amudarya”. The latter two were in charge of all the interstate canals of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers [46,47].

Although Article 10 of the document, which, in fact, was believed to preserve the Soviet principles, stated that “[t]he Commission and its executive bodies shall ensure that…sanitary water releases along the river channels and through irrigation system, and guaranteed water supply to river deltas are implemented”, the region saw a transboundary water conflict infringing the above-mentioned principle very soon. The conflict erupted between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, being the Tyuyamuyun reservoir, which is found in the delta of the Amu Darya, the point of contention between the two nations [27,48]. The source reports that the violent raids of 1992 were aimed at redirecting “drainage waters and…cut[ting] off pipes and irrigation canals.” Thereafter, Turkmenistan built another canal to divert the water they were entitled to from the Tyuyamuyun reservoir directly to the country’s territory, which caused certain problems for irrigation systems in several Uzbek regions [49] (p. 70). The water dispute over the Tyuyamuyun continued onwards [48]. Furthermore, as Ajay Kumar Chaturvedi [50] notes, “[t]hroughout the independence period, rumours have circulated of a small-scale secret war between the two states over the river resources.”

3.1.3. The Toktogul Reservoir, the Naryn River (1993)

The year of 1993, according to Guseynov and Goncharenko [49] (p. 70, own translation), saw “the first signs of hostility between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan in the field of water management”. That winter, which was marked by severe frost, Uzbekistan refused to supply piped gas to Kyrgyzstan since the Kyrgyz government was in debt [51]. As a result, Kyrgyzstan faced a serious energy crisis, which made it even more eager to exercise control over the Naryn’s water resources on a unilateral basis [52] (p. 94). In retaliation to Uzbekistan’s refusal, Kyrgyzstan, being one of the upstream counties—in other terms, one of those in position to control the flow of water to downstream neighbours—released great amounts of water that originated in the Tian Shan glaciers allegedly in order to generate badly needed electricity [49] (pp. 70–71). As Kumanikin ([36], own translation) states, the water release from The Toktogul reservoir, at that moment the largest one in Central Asia, “was performed so hastily and ignorantly” that the fast flow destroyed all the reservoirs down the stream. Later in summer, during the vegetation period, Uzbekistan, whose agricultural sector was the principal consumer of water, suffered from the reduced water supplies due to that short-sighted release [49] (p. 71).

3.1.4. Tensions between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (1997–2000)

In 1997 due to the escalation of the tensions between Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, the latter deployed 130,000 troops along the common border line; namely, on the leg where the Toktogul reservoir was located [27,53,54]. Karaev [54] states that the maneuver caused anger in Kyrgyzstan and prompted the Kyrgyz to adopt a resolution (1997) that declared water “a tradable commodity” and enabled Kyrgyzstan to obtain economic benefits from it.

According to Karaev [54], in February 1998, energy-rich Uzbekistan took a unilateral action of cutting off gas supplies to energy-deprived Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which provoked righteous indignation of the two countries. He states that the Kyrgyz government’s discourse on the matter was rather tough, and so was that of the Uzbek side, which appealed to Kyrgyz debt for its piped gas.

The long-termed disputes between the two nations led to the fact that Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan were on the verge of entering into an open conflict several times [49] (p. 71).

Butakov ([55], own translation) claims that “[i]n the winter of 2000 the water and energy conflict between Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan could have dissolved into an armed one”. According to the author, in retaliation to Uzbekistan’s refusal to supply gas to its energy-poor neighbour, Kyrgyzstan, being in dire need of power, released great amounts of water from the Toktogul reservoir, which resulted into the partial destruction of Uzbek downstream cotton fields. Uzbekistan deployed an airborne division in the vicinity of the Toktogul reservoir (near the Uzbek–Kyrgyz border) and conducted military exercise with armoured vehicles and helicopters aimed at occupying the strategic location [49] (p.71), [55,56] (p. 2), [57]. With regard to that step, the Kyrgyz threatened through a media leak that should the dam of the Toktogul reservoir be blown up, the formidable torrent would erase Uzbekistan’s Ferghana and Zeravshan Valleys from the map forever [27,48,49] (p. 71), [55,57].

3.1.5. Southern Kazakhstan Region (1997)

As previously mentioned, in October 1997, the Kyrgyz president Askar Akakev signed the resolution conferring on Kyrgyzstan the authority to capitalize on the water resources within its territorial borders [27,53,54]. According to Karaev [54], Kyrgyzstan had no further intention of sharing the water with its water-short neighbours without charge and threatened to trade with China if Uzbekistan failed to pay. The author states that Kyrgyzstan also demanded that Uzbekistan should pay the costs of releasing water to irrigate the downstream Uzbek farms and compensate revenue loss since the Kyrgyz did not use as much water as they could have used to generate electricity at their hydropower plants.

Subsequently, in the same year of 1997, several members of the Kyrgyz parliament applied to the head of World Bank’s mission in Bishkek claiming that “the status quo 1992 water agreement, unfairly, reflected only the downstream interests” [58] (p. 13).

Nevertheless, conflicts occur both between the downstream and upstream countries and between the downstream ones only. As Karaev [54] notes, Uzbekistan tends to cut water delivery that is provided by the upstream neighbours for its use and for that of Sothern Kazakhstan region. These unilateral actions provoke anger in Kazakh farmers [54].

The indignation, consequently, results into people’s protests, such as that occurred in July 1997 when Uzbekistan decided to cut off 70% of water flowing from its territory downstream, which threatened 100,000 hectares of the cotton and corn crops in the region of Southern Kazakhstan [27,53,54,59]. Taking into account that in 1997, there were about 18,000 farms in Maktaaral district in Southern Kazakhstan [15] (p. 261), the public anger became large-scale. As a result, on July 24, local Kazakhs organized a demonstration at the Kazakh-Uzbek border opposing to that decision of the Uzbek part [49].

3.1.6. The Civil War in Tajikistan and the Karakum Canal, Turkmenistan (1998)

Several months before the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Tajik SSR saw the beginning of a profound crisis caused by several internal factors [60]. It culminated in a civil war, which took place shortly after the collapse of the URRS, in May 1992 [61]. The most violent phase of the war lasted for a year, between July 1992 and July 1993. In that period the country was split into two factions: those who supported the newly formed government of President Rahmon Nabiyev and those who rebelled against it, called The United Tajik Opposition and represented by liberal democratic, Tajik nationalist forces and Islamist radical groups [60,61].

In 1994, the conflict began to de-escalate [60]. A total of three years later, a long peace process resulted into the signing of the June 1997 General Agreement through the mediation of the UN [62] (p. 64).

Although the peace progress was declared a success, a group of rebels opposed to the agreement as they did not approve of Emomali Rahmon as the new post-war president of Tajikistan and required that new elections should be held [27,63] (p. 13). They were led by Colonel Makhmud Khudoiberdiev, who initially supported Emomali Rahmon but then rose up against him [55]. In 1996, rebel troops under the command of Khudoiberdiev intended to occupy the capital of Khalton region but they were defeated and retired to Uzbekistan [64]. Two years later, in the autumn of 1998, they invaded the Tajik territory again occupying all the critical facilities of the cities of Khujund and Chkalovsk [64].

On November 6, Makhmud Khudoiberdiev stated that his men had mined one of the dams on the Karakum Canal and were ready to blow it up if the colonel’s demands were not met [63] (p. 13). He called that action a “deterrence measure” and added that once the reservoir, which was locally called a “sea”, because it was very extensive, was destroyed, its water would flood vast territories of Central Asia [63] (p. 13). It took the government a long time to react. Eventually, they claimed to have surrounded the rebel colonel’s headquarters and recaptured Khujund [63] (p. 13).

3.1.7. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Their Energy Swaps (1999)

Water and power have always been a negotiable trade and barter item in the arid region of Central Asia [65]. Nonetheless, the swap agreements between the energy-deprived and water-starved nations malfunction too often as they are broken by one or another side willing to defend its own interests.

In summer 1999, Tajikistan was reported to take unilateral action of releasing too much water from the Karakum reservoir [27,66,67]. The water release estimated at 700 million cubic metres was not expected by the downstream neighbours. Hogan notes that it resulted in reducing the water supply to cotton fields in southern Kazakhstan. Therefore, Kazakh farmers had to face significant damage. In the meantime, water-surplus Kyrgyzstan also cut the flow to southern plains of Kazakhstan since its energy-rich neighbour had failed to supply coal, in doing so breaking the terms of the swap agreement [66]. According to WHO data, Kyrgyzstan eventually managed to get badly needed energy sources from Kazakhstan. As Pannier [67] noted, “[t]he pressure worked”.

3.1.8. Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan (2000)

In 2000, two countries of Central Asian region also used water as a political tool [27,67]. According to Pannier [67], the initiator was Uzbekistan, which cut the water flow to Kazakhstan on the pretext of its failure to pay its debt. In retaliation, Kazakh government disconnected the telephone lines of the company that had been providing telephone service on both Uzbek and Kazakh territories making possible the communication between the two nations since the Soviet period [58]. The journalist states that, as a result, Uzbek customers were forced to contract the services of other providers (recently established by European companies, which were obviously more expensive) to be able to call any telephone user in northern Kazakhstan.

The only way out for Kazakhstan was to apply to the Tajik government and ask them for the bigger water release into the Amu Darya [67]. It is important to understand the fact that the river originates on the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, flows through Uzbekistan, then crosses Turkmenistan and runs into the Aral Sea on the Uzbek territory again. In other words, the Amu Darya is crucial for Uzbekistan water supply system as 9930 of Uzbekistan’s 17,777 water courses are found in the Amu Darya basin [68] (p. 2). Therefore, by turning to the Tajik government with this request, the Kazakhs expected to guarantee enough water to the Uzbeks, “so that the Uzbek government would be able to release more water from the Syr Darya into Kazakhstan” [67]. Tajikistan agreed to provide more water to Uzbekistan despite the shortage of water they were experiencing at that moment [67]. The journalist states that the main reason for their doing so was the hope to profit from Uzbek electricity later on, in the winter period. However, the Uzbeks, in defiance of all expectations, did not commit themselves to supply any water to Kazakhstan [67].

3.1.9. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (2001)

In June 2001, the tensions between upstream Kyrgyzstan and its downstream neighbour Uzbekistan rose sharply when the Kyrgyz parliament adopted a law which classified water as a commodity [27,69,70]. Two months later, the Kyrgyz government stated publicly that water-poor Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan would hence be charged for the water they made use of [69].

According to Khamidov [69], Kazakhstan tried to negotiate with Kyrgyzstan offering power engineering equipment and coal in exchange for water supply while Uzbekistan had no intention of making any bargain and was close to entering into an open conflict claiming that the new law was at odds with the international regulations. Moreover, Uzbekistan laid charges against the Kyrgyz for violating the terms of the agreement signed a year and a half before [69]. According to the document, Kyrgyzstan was to barter its hydroelectricity for Uzbek gasoline and oil. On top of that, Uzbekistan claimed that the Kyrgyz government was to clear its USD 1.75 million arrears in payment [69].

Afterwards, as Khamidov [69] states, Uzbekistan did not doubt to take enforcement action against “its much smaller and poorer neighbour” and ceased delivering gas to Kyrgyzstan.

It is believed that the interruption of gas supplies was ostensibly aimed at making the Kyrgyz change their mind on the water policy [69]. Contrary to what the Uzbeks might expect, the Kyrgyz First Deputy Prime Minister insinuated that the lack of gas would compel them to produce more electricity on their hydropower plants reducing, thereby its exports to downstream states [69].

3.1.10. The Chardara Reservoir, the Syr Darya River (2002–2004)

In 2002 Uzbekistan initiated the intensive development of the Aydar-Arnasay lake system, a human-made system comprised of three saline lakes located in the salt flats of south-eastern Kyzylkum desert, Uzbekistan [71,72,73], [59] (pp. 116–117). Formed in 1969, the system had been used to control the water level in the Chardara reservoir preventing the Syr Darya flow from damaging the downstream territories [59,71,72] (pp. 116–117). Water discharges from the Chardara to the Ardar-Arnasay provided security for the whole Kyzylorda region, Kazakhstan [49] (p. 69).

Nevertheless, in 2002 the Uzbeks decided to build new storage dams that would enable them to accumulate the Charadara freshwater separately from Ardar-Arsanay saline water [73]. Shemratov states [73] that the dam construction was started without consent of the Kazakh side, which by that time had already foreseen its potential repercussions: the future dams would make the water release from the Chardara impossible in case of its overcharging.

In 2003, the Kazakhs’ worst fears were realized. The water in the Chardara reservoir was constantly rising till it reached the critical level causing the dam to burst [49] (p. 69), [74]. The government took urgent measures in order to fight the flood in the Kyzylorda region [49] (p. 69), [74].

Nonetheless, the issue was not solved and, in January 2004, due to the intensive precipitation, the water level in the Toktogul reservoir, Kayrakkum reservoir and the Chardara reservoir rose drastically and people from the Kyzylorda region found themselves under the threat of flood again [49] (p. 69), [74].

3.1.11. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (2008)

In spring 2008, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, both water-rich nations that had always had rather amiable relations, came into an open conflict over the state borders and shared water resources [27,75]. According to Kadykeev [75], the dispute began with the clash between Tajiks and Kyrgyz officials in March, when approximately 150 Tajik civilians and police officers from Isfara region crossed what was considered, by Kyrgyzstan at least, the frontier. Their intention was to demolish the dam that obstructed an irrigation canal which supplied water not only to the Kyrgyz territory but also to the surroundings of the Tajik village Hoja Alo [75].

The dam in concern was situated in a zone where the Kyrgyzstan–Tajikistan border was unclear, firstly, due to “Central Asia’s difficult terrain”, which did not allow marking boundaries directly on the ground and, secondly, due to the existence of at least two maps with the boundaries marked differently on either of them [75].

Kyrgyz border guards arrived at once and dispersed the Tajiks [75]. Kadykeev [75] notes that the incident seemed to start improving when the Kyrgyz officials consented to reopen the dam so that the Isfara region could get its water.

Nevertheless, on March 27, another hundred and a half Tajik civilians and border guards crossed the frontier planning to “clear the channel of the Isfara river” [75]. They were soon evicted by the Kyrgyz border service [75].

As Kadykeev [75] states, the next day, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic expressed its concern over the clashes. He urged upon the Tajiks the importance of taking measures to prevent similar incidents in the future [75].

Kadykeev [75] points out that a lot of political rhetoric ensued from the two alleged invasions. The Tajiks were believed to have acted so decisively as the Kyrgyz had not notified them that the waterway was going to be shut off for clearance and refurbishment [75]. Hence, according to the author, the Tajiks found themselves totally deprived of irrigation water for more than a week during the vegetation season which is crucial for agriculture. Moreover, the major of Isfara stated that until the demarcation was completed and ratified by both countries, the territory was considered under dispute, therefore no agricultural or construction work could be allowed there, let alone the damming of the canal [75].

3.1.12. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (2010 and 2011)

Kadykeev [75], citing the opinion of some regional experts, claims that the “growing pressure on land and water resources in the heavily populated Fergana valley means clashes of this kind [like the conflict in concern] will happen again, and could potentially escalate into broader conflict”.

Eventually, their fears came true. Sanjar Saidov [75] in his article, which covers the tensions related to the construction of the Rogun Hydropower Plant, mentions at least two border incidents that “acutely exacerbated the difficult relations between the neighbouring republics”: the first one took place in February 2010 between the Tajiks and Uzbeks and the second one occurred in December 2011 between the Kyrgyz and Uzbeks. Kadykeev’s statement [75] is also proved by the fact that in 2015, speaking about the conflict over the Rogun Hydropower Plant, Saidov notes [76], “The current phase of this water and energy dispute began in 2008”, pointing out the complexity of diplomatic negotiation between the states of Central Asia.

3.1.13. Uzbek Gas Supply to Tajikistan (2012)

In April, 2012, Uzbekistan cut gas supply to Tajikistan, unilaterally and without any notice [27,77]. According to the Kozhevnikov [77], the abrupt stoppage that lasted for more than two weeks threatened the whole Tajik economy as it destroyed the expansion plans of the state-run aluminium smelter and disabled the functioning of the state-run cement plant. The two factories have always been crucial for the economic wellbeing of the country. Additionally, the aluminium smelter had been the main source of export earnings of Tajikistan [78].

The severance of gas supplies resulted from the expiration on March of the three-month bilateral contract between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, according to which Uzbekistan were to pump about 15 million cubic metres of gas to Tajikistan every month [77]. The Tajik authorities had not bothered to renew the contract in good time, and neither did the Uzbek side. On the contrary, Uzbekistan had stated that it was in need of extra gas to sell it to China [77].

Some Tajik experts claim that the gas supply was shut off rather for political reasons than for the economic ones. Both the cement and the aluminium producers contributed significantly to the construction of the gigantic Rogun Hydropower Plant [77,78]. The colossal project was not approved by Uzbekistan since the government believed it would drastically reduce the water flow meant for the downstream countries [77,78]. Moreover, Uzbekistan appealed to the international community charging the state-run aluminum smelter with releasing environmentally harmful emissions on the Uzbek territory [78].

According to Kozhevnikov [77], after the 15-day cessation of gas supplies, a new contract was signed guaranteeing that Tajikistan would receive the supply of 155 million cubic metres of Uzbek gas till the end of the year.

3.1.14. The Rogun Dam, the Vakhsh River (2012)

One of the most heated debates concerning water-energy issues is that over the Rogun Dam on the Vakhsh River, Tajikistan [27,79]. The main opponents are energy-deprived Tajikistan and agriculture-centred Uzbekistan. The clash of interests between the two countries affects the everyday life of tens of millions of people [80].

Being the poorest nation of Central Asia, the Tajiks often fail to meet the bills they are presented with. Thus, the natural gas deliveries from Uzbekistan are frequently ceased, which leads to power shortages all over Tajikistan, especially during the winter [78,80]. From the Tajik President Emomali Rahmonh’s perspective, the only solution to the problem of scarce imported energy resources is the colossal project of the Rogun Dam. The highest dam in the world would be able to convert impoverished Tajikistan not only into an energetically independent country, but also into a competitive electricity exporter to the whole region [78,79,80].

The construction of the Rogun Dam began in the 1980s but was suspended after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In 2004, Emomali Rahmonhe relaunched the project, having great hopes for it [78,80]. The idea of a gigantic dam providing with electricity even the farthest corners of Tajikistan gained significant popularity among the common Tajiks. Nevertheless, the Uzbeks are not so enthusiastic about the resumed construction, which poses real threats to the Uzbek economy, ecological sustainability and the safety of millions of people. The Uzbek government is openly opposed to the project, which is confirmed by the mutual harsh rhetoric [78,79,80].

Firstly, the functioning of a 335 m dam will impair the intensive irrigation needed for the Uzbek vast cotton fields as the water flow will be drastically reduced by the time it gets to downstream Uzbekistan. Consequently, if the water deficit in Uzbekistan increases, the cotton harvest will be at stake [78].

Secondly, the Uzbek President Islam Karimov pointed out that the geographical features of the Rogun’s location will make it extremely vulnerable to earthquakes. The break of the dam might lead to a large-scale flood claiming a great number of lives [78,80].

Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan was raising funds for its own dam project called Kambarata. The dam was also expected to solve out the problem of power cutoffs and generate excessive electricity intended for export [79].

Though Turkmenistan was to experience the same repercussions, the Turkmen President abstained from supporting his Uzbek counterpart [80].

In 2012, the World Bank in its attempt to dissuade the Tajik President from constructing the gigantic dam brought forward a variety of ecologically sustainable and secure ways of fighting the energy crisis in Tajikistan. However, Emomali Rahmonhe was unwilling to change his mind and insisted on the construction’s being continued. Therefore, the Tajik President’s steadfast stance sharpened the already tough rhetoric even more [80].

In September, 2012, Islam Karimov stated that the situation “could deteriorate to the point where not just serious confrontation, but even wars could be the result” [79,80].

During the Tajik Civil War, it had been the Uzbek President and his military support that enabled Emomali Rahmonhe to come to power. Therefore, Islam Karimov expected the Tajik President to bend his own will and serve the interests of the Uzbeks. However, it never happened. President Rahmonhe played his own game in the best interest of his country [78].

Apart from the rhetoric, Uzbekistan took strong-arm measures, which caused the legitimate indignation on the part of the Tajiks. The Uzbeks banned rail import, stopped Tajik trains at the border alleging “technical difficulties” and introduced some other economic and transportation sanctions like the closure of border checkpoints [78,80]. In addition, they did not allow Turkmenistan to transmit its electricity to Tajikistan over Uzbek territory [80]. On top of that, Uzbekistan mined the borderline with the intention of impeding radicalized Muslims and drug dealers from crossing the frontier [78,80]. According to Central Eurasia Standard [80], at least 76 civilians were killed.

Currently, the construction has not been halted and the conflict has not been settled either. In 2020–2022, the Tajik government plans to invest about USD 1.1 billion into the project. The dam already has two turbines installed; the starting of the third one is planned for 2025 [81].

3.1.15. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (2013)

In July, 2013, about fifty residents from the Kyrgyz village of Kok-Say situated on the border with Kazakhstan blocked a canal which delivered water to a number of villages in southeastern part of the neighbouring country [27,82]. By plugging the flow of water to the adjacent territory, the Kyrgyz intended to compel the Kazakhs to give back a 2600-hectare plot of land that used to form part of Kyrgyzstan but was later ceded to Kazakhstan in accordance with the border agreement of 2001 [82,83].

It is worth remarking that in conformity with the above-mentioned document, Kyrgyzstan was not deprived of its territories without compensation. In fact, the Kyrgyz did get another plot of the same square footage in exchange [82].

Lilis states [82] that while seeking to achieve its goal, Kyrgyzstan made it impossible for the Kazakh to irrigate about 4000 hectares of their farmland. With the harvest being threatened, the governments decided to intervene in the conflict. The canal remained blocked for 10 days and the flow was restored only on July 17, after the telephone talk between the two Prime Ministers [82].

According to Lillis [82], the Kazakh side stated that they expected their neighbour to prevent such incidents from occurring in future. Although the conflict was completely resolved, it pointed out the potential for future disagreements over land and water resources among the countries of Central Asia.

3.1.16. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (2014)

In January, 2014, there was a clash between Kyrgyz and Tajik board guards over the construction of a road on disputed territory [27,84,85]. The shootout took place not far from the Kyrgyz village Of Ak-Sai, wedged between Tajikistan and the Tajik exclave of Vorukh [86].

This contested territory had been the scene of regular disputes over the access to water resources and pasture areas, which had constantly aggravated ethnic hostility in the area [85]. According to Trilling [84], the reasons for all those confrontations remained the same–the lack of clear border and the weak governments. The negotiations on demarcating the border had been stalemated for years as neither of the sides was ready to assume responsibility of setting a boundary through multiethnic villages [84].

Trilling states [84] that the incident in concern was unusual compared to the previous ones. Generally, conflicts of that kind arise between civilians from one country and troops from the other while the January 11 clash did not involve civil villagers.

The catalyst for the clash was Kyrgyz intention to construct a road in the disputed zone, which the Tajiks opposed firmly [84]. Kyrgyz officials alleged that the Tajiks had brought their mortars into action targeting such strategic facilities as a small-scale dam and an electricity substation [84,86]. The Tajik side neither confirmed nor denied the accusation. Tajik and Kyrgyz authorities expressed polar opinions on who had been the first to open fire. The former stated that Kyrgyz security forces fired first whereas the latter believed the Tajik were to blame for unleashing the aggression. One way or the other, at least five Kyrgyz and two Tajik guards were injured in the shootout [84,85,86].

Taking everything into account, it is believed that the January 11 clash drastically exacerbated the long-lasting tensions in the multiethnic region with no strict demarcation [84].

3.1.17. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan (2014)

The Fergana Valley has always been the scene of endless interethnic conflicts over the access to water. The fertile valley, which attracts people by its high agricultural productivity, for some of the locals, turns out to be dry and inarable terrain because of the scarce irrigation. The misuse of water by upstream countries has forced their downstream neighbours to fight desperately for every drop of this valuable resource so that their harvest would not be destroyed by the scorching sun. The confrontation is intensified by the fact that the canal network that distributes water to the farms passes through disputed lands and numerous enclaves, leading to great losses of water on the way to its destination as well as the regulation of the water flow by the nations whose territory it runs over [27,87].

One of the most blatant examples of such inequitable distribution is that experienced by the residents of the Kyrgyz village of Kok Tal. Villagers get their water from a source situated 120 miles away [87]. Arnold states [87] that after its long journey across the Uzbek territory, the water finally reaches the Kyrgyz farms, but its volume is twice as small as it was when it was passing through the Uzbek territory.

According to the executive director of the Central Asian Alliance for Water, conflicts over irrigation water occur on a daily basis during the summer period. He even claims that some people have been killed over irrigation water [87].

In 2014, an Uzbek farmer was killed while waiting patiently for his share of irrigation water, reports Arnold [87]. The murderer was a Kyrgyz who stated that the Uzbeks had no right to water. He hit his neighbour with a spade and soon the victim died.

That summer, Kyrgyzstan saw the worst drought in more than 20 years. Additionally, the climate in the region has been getting hotter and hotter, causing the melting of the glaciers that feed Syr Darya and Amu Darya, two main rivers flowing through the Fergana Valley [87].

3.1.18. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (2018)

One of the reasons for Kyrgyzstan’s violent disputes with Tajikistan is the open border between the two countries [5,87].

Arnold states [87] that in the summer of 2018 there were two conflicts between the residents of the Kyrgyz village of Ak Sai and Tajiks from the neighbouring enclave of Vorukh. During one of the contentions, people were reportedly taken hostage. The other involved a hundred men clashing over the installation of a water pump. In both cases, armed guards were summoned to stabilize the situation [87].

While the authorities avoided being interviewed by the press, the villagers of Ak Sai openly accused the Tajiks of shutting off the access to water for Kyrgyz people. Youth groups blocking the road with their cars and fighting each other became a common sight in the frontier zone [87].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

After analysing all the conflicts (which reinforces the school of thought of the water wars within the hydropolitical literature), paying special attention to their origin, evolution and eventual resolution, or their possible future escalation (in the case of the conflicts that were not fully resolved), we can conclude that Central Asia is a region very prone to conflict over water. Moreover, its capacity to create conflicts was underestimated as we can clearly see that in most cases, given the regional context where the relations between the states are not oriented towards cooperation but towards conflict, the regulation of the conflicts did not follow any clean-cut course of action, lacked cooperation and flexibility and, thus, resulted inefficient and required more time and human resources to, at least, diminish conflict intensity.

Thus, despite comprising only five states, Central Asia saw at least twenty conflicts in thirty years (1990–2019). It should also be noted that, in certain years (1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2012, 2014 and 2018) there were two conflicts. The basis of the conflicts varied although in all of them it was a certain clash of interest that propelled different groups toward conflict. In most conflicts, water played the role, in whole or in part, of a trigger. Furthermore, most conflicts involved two or more states, or two or more actors (communities, groups) that came from different states. The two conflicts in which water played the unique role of casualty (1998 and 2014), were not isolated conflicts; they were conflicts that were developing in the context of regional conflict dynamics over water and involved the states or major actors: Tajik guerrilla in the first case, and the security forces in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the second case. This is also true for the three conflicts in which water played the unique role of weapon (1997, 1999 and 2000). All these conflicts also revealed the strategic value of water in the region.

As a result of the analysis, we can group the concrete causes of conflicts:

- The clash of interests between the upstream countries rich in water but poor in gas or oil and the downstream states, which have fossil fuel deposits but a constant lack water, which they get from their water-surplus neighbours. While Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan prefer releasing water in winter to generate badly needed electricity, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan are in dire need of water during the vegetation period to be able to irrigate their crops [5]. Thus, either Uzbek agricultural sector is threatened by growing desertification, or Tajik households and businesses are hit by blackouts.

- Unsteady electricity and water supplies. Since the downstream countries began to sell (not to provide free of charge) gas and electricity to their neighbours and cut off the supplies if they failed to pay in time, upstream countries have suffered from energy deficits. At the same time, the upstream countries have cut off the water flow whenever they found it necessary to defend their interests.

- The shortage of the land apt for living and agriculture, which is determined by the access to water. The scarce furtive soil resources are mainly found in the heavily populated Fergana Valley, which has been the scene for numerous clashes due to its multiethnic population (the valley is officially divided among three states: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan).

- Shared water resources and water systems. The points of contention are generally the following: irrigation canals, pipes, dams, reservoirs, and hydropower plants.

In order to classify the conflicts, we can divide them into bilateral, trilateral, and intrastate conflicts.

The trilateral conflicts (1999, 2000) erupted over the water provided by the water-surplus countries and electricity supplies provided by the energy-rich ones. Contentions of this kind are not unusual since each of five countries, to a greater or lesser extent, is dependent on the resources it gets from its neighbour. Therefore, it appears sensible that each country aspires to become more independent in water and energy terms. One of the greatest political aspirations of the kind was the Tajik colossal project of the Rogun Dam. It was supposed to allow extremely poor Tajikistan to put an end to the constant blackouts, to become energetically self-sufficient and, additionally, to generate enough electricity to export it to the rest of Central Asia. As Filippo Menga states [88], such political campaigns are aimed at converting the construction of a huge dam into a patriotic project. According to Menga [89], “dams tend to be surrounded by a rhetorical discourse that emphasises their contribution to a prosperous future and to the realisation of national goals while nurturing development and progress”. Nevertheless, as noted earlier, the project has faced a lot of criticism on the part of those states which claim that the ongoing construction infringes upon their water rights. Menga [88] underlines that, for local people, the inevitable consequences of colossal projects like this “include landscape changes, loss of cultural heritage sites, and resettlement policies”. At the same time, at the state level, the implementation of a huge dam affects “irrigated land, flood control, and electricity generation” [88]. Anyway, the Rogun hydropower project needs significant funding and it is not at an advanced stage of construction yet.

Intrastate conflicts are connected to extreme violence and huge risks for a large number of civilians. They are the consequences of the struggle for power (1998) or the acute interethnic tensions (1990). One more time, we can see that even those conflicts which are technically confined to only one state, in practice, are connected to more than one nation or ethnicity: the Uzbek government harbouring the rebellious Tajik colonel [64]; the bloody ethnic clashes in the Kyrgyz region of Osh.

The bilateral conflicts are the most numerous and they are very often based on border clashes, electricity supplies, and disputed water resources or water systems (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 4.

Bilateral conflicts in Central Asia (1990–2019).

Table 5.

Intrastate conflicts in Central Asia (1990–2019).

Table 6.

Trilateral conflicts in Central Asia (1990–2019).

Table 7.

The number of conflicts in the countries of Central Asia (1990–2019).

The above-given tables illustrate the conflict potential of each state. Here, we can see that the most conflict-prone states are Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, with 12 and 13 conflicts, respectively. The least number of conflicts broke out in Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, two and five cases, respectively. Tajikistan, having seen nine disputes, surpasses the average number of conflicts per country. Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan entered into an open conflict six times. The contentions erupted principally over water management, housing shortage and scarce lands, energy production, and trade disagreements (over water and energy, as well).

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan clashed five times (considering both bilateral and trilateral conflicts) for the same reason: unclear border and unauthorized actions on the disputed territory concerning shared water systems. Hostilities between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan erupted four times (considering both bilateral and trilateral conflicts). The conflicts concerned water management and energy supplies. It is worth mentioning that three of them were directly or indirectly connected with the construction of the Rogun Dam. Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan, both downstream countries, which are experiencing land degradation and desertification, however, were not affected by many conflicts.

The present article has illustrated the direct and clear connection between the conflicts in Central Asia, and water. Water played an important role in the relations between the five countries of Central Asia region. Therefore, what was, in qualitative terms, the real capacity for the direct and indirect generation of conflicts of water as a resource with great strategic value due to the unequal distribution of water in a region like Central Asia, whose states are not oriented towards cooperation but towards conflict, in the period of 1990 to 2019? All things considered, we come to conclusion that in the years 1990 to 2019, in a regional context such as Central Asia, where the relations between the five states are not oriented towards cooperation but towards conflict, the unequal regional distribution of water has made it a natural resource with great strategic value and that in qualitative terms has had a very high real capacity for the direct and indirect generation of conflicts.

5. Recommendations

Finally, we will propose some recommendations on the resolution of water conflicts in Central Asia, based on the lessons drawn from the events that occurred in the region. These recommendations can also be applicable to other regions with similar characteristics.

We will point out the following general and contextual recommendations, which are interrelated:

- (a)

- Firstly, the creation of a cooperative context and truth-based relations between the states of the region.

- (b)

- Secondly, the consolidation of stronger and more responsible governments, which will prevent the negotiations between the states from coming to deadlock or collapsing.

- (c)

- Thirdly, the clear border demarcation between the states.

- (d)

- Fourthly, the fight against environmental destruction led at the regional level.

Now, we will point out some concrete recommendations that refer directly to conflicts over water:

- (a)

- Firstly, the drafting of an effective legislation in the field of water management (particularly for shared water resources and water systems) and its compliance by all the states in the region.

- (b)

- Secondly, to stipulate in this legislation the management and the trade of hydrocarbons so that the exchange of water (both for agricultural use and electricity generation) and hydrocarbons between the states of the region should be beneficial and peaceful for all of them.

- (c)

- Thirdly, in connection with the above-mentioned suggestion, to achieve steady electricity and water supplies to the states of the region.

- (d)

- Finally, to ensure that this exchange provides greater availability of water for the most water-deprived countries, for human consumption and, above all, for agricultural use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.P.-R., P.B. and D.F.; Data curation, J.A.P.-R. and P.B.; Formal analysis, J.A.P.-R., P.B. and D.F.; Investigation, J.A.P.-R., P.B. and D.F.; Methodology, J.A.P.-R., P.B. and D.F.; Project administration, J.A.P.-R. and P.B.; Resources, J.A.P.-R. and P.B.; Supervision, J.A.P.-R. and P.B.; Validation, J.A.P.-R. and P.B.; Writing—original draft, J.A.P.-R. and P.B.; Writing—review & editing, J.A.P.-R. and P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Peña-Ramos, J.A. The Impact of Russian Intervention in Post-Soviet Secessionist Conflict in the South Caucasus on Russian Geo-energy Interests. Int. J. Confl. Violence 2017, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Amirov-Belova, D. The role of geo-energy interests of Russia in secessionist conflicts in Eastern Europe. Int. J. Oil Gas Coal Technol. 2018, 18, 485–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Bagus, P.; Amirov-Belova, D. The North Caucasus Region as a Blind Spot in the “European Green Deal”: Energy Supply Security and Energy Superpower Russia. Energies 2021, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Ramos, J.A. Russia’s geo-energy interests and secessionist conflicts in Central Asia: Karakalpakstan and Gorno-Badakhshan. Int. J. Oil Gas Coal Technol. 2020, 25. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Suleymen, M. Vodny Resursy Kak Factor Bezopasnosti v Tsentralnoy Azii [Water Resources as a Safety Factor in Central Asia], Vestnik KazNU, Almaty. 2011. Available online: https://articlekz.com/article/7850 (accessed on 30 October 2020). (In Russian).

- Homer-Dixon, T.F. On the threshold: Environment changes as causes of acute conflict. Int. Secur. 1991, 16, 76–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer-Dixon, T.F. Environmental Scarcities and Violent Conflict: Evidence from Cases. Int. Secur. 1994, 19, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleick, P.H. Water and Conflict: Fresh water resources and international security. Int. Secur. 1993, 18, 79–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, B.; Carius, A.; Conca, K.; Dabelko, G.; Kramer, A.; Michel, D.; Schmeier, S.; Swain, A.; Wolf, A. The Rise of Hydro-Diplomacy: Strengthening Foreign Policy for Transboundary Waters; Federal Foreign Office/Adelphi: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeier, S. Resilience to Climate Change Induced Challenges in the Mekong River Basin: The Role of the Mekong River Commission (MRC); World Bank Water Working Note; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeier, S. The Organizational Structure of River Basin Organizations: Lessons Learned and Recommendations for the Mekong River Commission; MRC Technical Paper; MRC: Vientiane, Laos, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitoun, M.; Warner, J. Hydro-hegemony—A framework for analysis of trans-boundary water conflicts. Water Policy 2006, 8, 435–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerich, K. Hydro-hegemony in the Amu Darya Basin. Water Policy 2008, 10, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, P. Saving the Mediterranean: The Politics of International Environmental Cooperation; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dukhovny, V.; Schutter, J. Water in Central Asia: Past, Present, Future; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitoun, M.; Mirumachi, N.; Warner, J. Transboundary water interaction II: Soft power underlying conflict and cooperation. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2010, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cascão, A.E. Changing power relations in the Nile river basin: Unilateralism vs. cooperation? Water Altern. 2009, 2, 245–268. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H. The Guarani Aquifer System, highly present but not high profile: A hydropolitical analysis of transboundary groundwater governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 83, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H. Yarmouk, Jordan, and Disi basins: Examining the impact of the discourse of water scarcity in Jordan on transboundary water governance. Mediterr. Polit. 2018, 24, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista da Silva, L.P.; Hussein, H. Production of scale in regional hydropolitics: An analysis of La Plata River Basin and the Guarani Aquifer System in South America. Geoforum 2019, 99, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudy, M. Hydro-hegemony and international water law: Laying claims to water rights. Water Policy 2008, 10 (Suppl. 2), 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conker, A.; Hussein, H. Hydropolitics and issue-linkage along the Orontes River Basin: An analysis of the Lebanon-Syria and Syria-Turkey hydropolitical relations. Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2020, 20, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; Conker, A.; Grandi, M. Small is beautiful but not trendy: Understanding the allure of big hydraulic works in the Euphrates—Tigris and Nile waterscapes. Mediterr. Polit. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L. Contexts and constructions of water scarcity. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2003, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, G.; Bulkeley, H.A. Heterotopia and the urban politics of climate change experimentation. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2018, 36, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, J. The sustainability and resilience of global water and food systems: Political analysis of the interplay between security, resource scarcity, political systems and global trade. Food Policy 2011, 36 (Suppl. 1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacific Institute. Water Conflict Chronology. Available online: https://www.worldwater.org/water-conflict/ (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Hatami, H.; Gleick, P. Chronology of conflict over water in the legends, myths, and history of the ancient Middle East. In Water, War, and Peace in the Middle East; Environment; Heldref Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; Volume 36, pp. 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Millions of People Risk Being Cut off from Safe Water as Hostilities Escalate in Eastern Ukraine—UNICEF. 4 July 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/millions-people-risk-being-cut-safe-water-hostilities-escalate-eastern-ukraine (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Barbeito Cuadri, A.J. El Agua Dulce en la Agenda de Seguridad Internacional de Comienzos del Siglo XXI; Documento de Opinión n.º 67/2013; Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, Ministerio de Defensa (Gobierno de España): Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ICWC. Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia. Available online: http://www.icwc-aral.uz/index.htm (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- Qobil, R. Waiting for the Sea: BBC Central Asian Services. 25 February 2015. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/resources/idt-a0c4856e-1019-4937-96fd-8714d70a48f7 (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- GRID-Arendal. A Non-Profit Environmental Communications Centre. Available online: https://www.grida.no/resources/7385 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- ENVSEC. Environment and Security in the Amu Darya Basin, UNEP, UNDP, UNECE, OSCE, REC, NATO. 2011, p. 14. Available online: http://www.cawater-info.net/library/eng/amudarya-envsec-en.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- CAWater-Info. Database. Available online: http://www.cawater-info.net/bd/index_e.htm (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Russell, M. Water in Central Asia: An Increasingly Scarce Resource: European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS). 2018, pp. 4–5. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/625181/EPRS_BRI(2018)625181_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. AQUASTAT Database. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/data/query/results.html?regionQuery=true&yearGrouping=SURVEY&showCodes=false&yearRange.fromYear=1960&yearRange.toYear=2015&varGrpIds=4250,4251,4252,4253,4257,4275&cntIds=®Ids=9727&query_type=RegProf&newestOnly=true&_newestOnly=on&showValueYears=true&_showValueYears=on&categoryIds=-1&_categoryIds=1&XAxis=VARIABLE&showSymbols=true&_showSymbols=on&_hideEmptyRowsColoumns=on&lang=en (accessed on 30 October 2020).

- CAWater-Info. Safety of Large Hydraulic Structures (Dams, HPP, Reservoirs). Available online: http://www.cawater-info.net/bk/1-1-1-1-4_e.htm (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Burunciuc, L. Improving Water and Sanitation in Central Asia Requires Determination and Shared Commitment. World Bank Blog, 24 December 2019. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/europeandcentralasia/improving-water-and-sanitation-central-asia-requires-determination-and-shared (accessed on 29 October 2020).