2.1. Sport Spectatorship as a Consumer Behaviour in the Context of SMEs

Sport as a leisure activity has developed into two distinct behaviour patterns, albeit with the same origin: participation and spectatorship ([

9,

19]). Although they share the same origin, each pattern has retained its heterogenous qualities in its actualisation, such as motives, attitudes, and determinants [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Elias and Dunning [

9] described these two intrinsic ambivalences in spectator behaviour, stating that “…from these earlier days, the term sport was never confined to participant sport alone: it always included contests undertaken for the enjoyment of spectators, and the principal physical exertion could be that of animals as well as humans” (p. 8). Guttmann [

10] further proposed that a substantial distinction between the “player” and “spectator” roles was not made until the 17th century, when sport was modernised through the civilising processes of rationalisation, specialisation, and professionalisation. Conversely, the acts of “playing” and “watching someone play” were originally carried out simultaneously. In contrast, scholars such as Kenyon and McPherson [

25], Tokuyama and Greenwell [

26], and Zillmann et al. [

27] showed a somewhat integrated view, asserting that there is a relationship between participation and spectatorship behaviour, and that the two interact with each other such that the former acts as an antecedent to the latter, or vice versa. Considering sport as an active leisure activity, Henderson [

28] postulated that these two activities lie on opposite ends of the spectrum: spectator sport is described as “organized entertainment”, whilst participant sport involves “physical exertion”.

According to Roche [

29], SMEs are defined as large-scale sporting events, which have a dramatic character, mass popular appeal, and international appeal. Furthermore, Horne [

30] stated that SMEs seem to have significant consequences for the hosting nations where they occur, alongside the huge media coverage that they attract. From the perspective of SMEs, because of the distinctive value that each sport behaviour holds in regard to sport consumption, the two pillars of sport consumption behaviour have been developed differently based on the role that each of them plays in SMEs. Sport participation, on one hand, has become one of the impacts, often called legacy, generated from SMEs as an outcome in association with health benefits [

6,

16,

18]. Legacy, in the context of SMEs, can be defined as the tangible or intangible outcomes or by-products generated for and by an SME that remained in the minds of the spectators longer than the event lasted, whether this was planned or unplanned by key stakeholders [

17]. Sport participation, therefore, is categorised as a part of a sport legacy, defined as an intangible promotion of health through sport participation, due to spectators becoming inspired by an SME and subsequently participating in sport themselves [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Sport spectatorship, on the other hand, has become a key driver for spectators to attend/watch SMEs due to the entertainment value derived from international sporting competitions. Sport spectatorship was originally defined as individuals “observing” athletic contests at certain cites [

10]. However, sport spectating has become facilitated by commercial entities because of its profit-generating potential, largely through the professionalisation of sport. Furthermore, spectating behaviours have become diversified through the development of media technology, allowing spectators to observe events directly (e.g., attending themselves) or indirectly (e.g., watching sport events online or on mobile devices) [

10,

31]. The sport spectatorship literature has identified various motivational factors influencing spectator involvement and related behaviours that provide an insight into what makes individuals watch/attend sports events [

21,

22].

In response, a wide variety of spectator motivations have been defined and developed based on the environment and cultural background where each spectating behaviour occurs. However, as with sport participation, sport spectatorship can be an outcome in the form of an intangible aspect of sporting culture or a phenomenon that SMEs generate, especially in hosting nations. As Horne [

32] illustrated, SMEs in the 21st century have evolved into commercially motivated global sport spectacles, promoted by corporate sponsors, media, local governments, and international governing bodies. SMEs are used as effective communication and commercial channels in order to influence sport consumption behaviour sustainably [

32,

33].

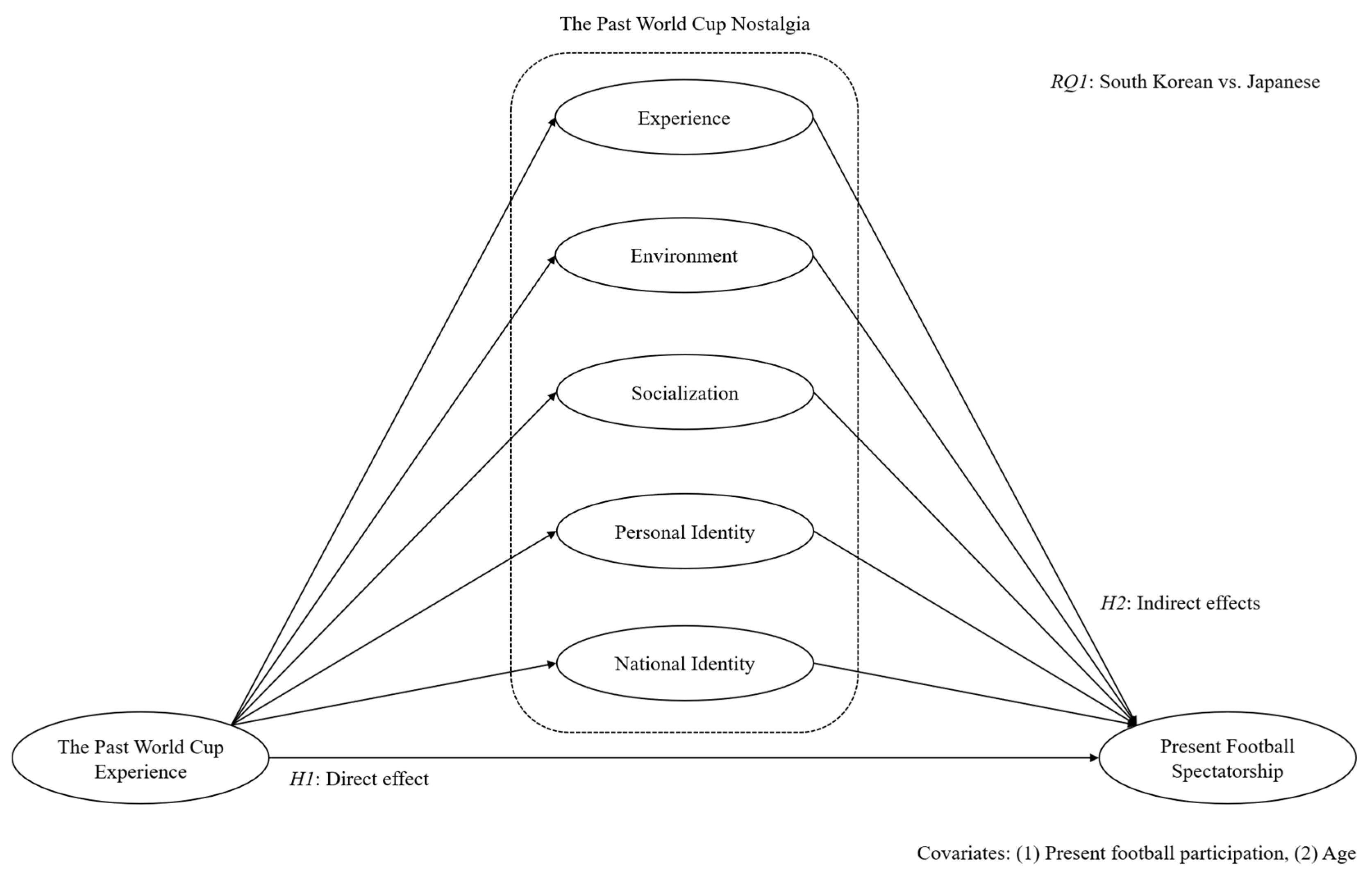

Considering the inherent features of sport, the historical and commercial development process of consumer behaviour, and the influence of contemporary SMEs on sport, the present study posits that the effect of SMEs on sport legacy should not necessarily be limited to participation but should extend to spectatorship outcomes as well. This extended scope, in terms of a sustainable sport legacy, provides sport marketers and policymakers with a better understanding of the complexity of SMEs, especially the changes in the behaviour patterns of spectators in host countries. Our research framework is presented in

Figure 1, and our first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

The past World Cup experience positively influences present football spectatorship behaviour.

2.2. Nostalgia as a Psychological Construct in Sport Tourism, Marketing, and SMEs

An individual’s past memories often motivate them to take a certain course of action. This decision-making process (e.g., the motive for buying) is influenced by emotional characteristics, such as a longing for the past [

34], and is associated with an emotional state commonly called nostalgia. In recent studies in modern psychology, nostalgia is described as having some motivating potential [

35,

36]. Boym [

34] suggested that contemporary pop culture has created a nostalgia industry that brings the past back to life, making past events more tangible in order to exploit them commercially. The commercial value of nostalgia is also supported by scholars in marketing management, who have suggested that nostalgia creates emotions that, in turn, lead to the formation of preferences and influence the buying motives and consumption behaviour of consumers [

36,

37,

38,

39].

In sports, nostalgia acts as an important communication channel with consumers, and is mainly found in the fields of tourism, consumer marketing, and SMEs. In sport tourism, nostalgia has often been integrated into building an image and raising awareness of specific destinations or tourist attractions [

40]. The association of past memory with a readily formed image of the destination motivates tourists to visit specific places again [

41,

42,

43]. The importance of triggering motives for future travel derived from past memories has been gaining attention ever since the tourism industry became important for the economic growth of many countries [

44].

Similarly, the sport consumer marketing industry considers nostalgic feelings among consumers as a key retaining strategy [

37,

38,

45,

46]. Commonly referred to as retro marketing, this strategy is used by professional sport teams, leagues, and the media. They incorporate past memories into marketing strategies, involving images, merchandising, venues, promotions, and advertising in order to communicate with fans, suggesting that nostalgic feelings evoked by objects or past experiences generate a positive influence on consumer responses [

47].

It is apparent that both tourism and consumer behaviour domains use nostalgia as a core element of their marketing communication, acknowledging it as an effective means of influencing consumer behaviour [

38]. In both domains, nostalgia is seen to have cognitive and affective states, evoked by external stimuli. This generates strong positive responses [

37,

46,

47,

48].

Sports mega-events are often viewed as lieu de mémoire [

49,

50,

51], a phrase originally coined by the French historian Pierre Nora [

52], roughly translating to “realms of memory”. Nora [

52] stated that “A lieu de mémoire is any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by dint of human will or the work of times has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community” (p. 8). Through this concept, the author described the symbolic significance of past collective memory, which is responsible for forming attitudes and constructing one’s identity using the individual memories one has accumulated.

SMEs have a notable social and psychological significance. They are perceived metaphorically as places of collective memory. Furthermore, the effect of nostalgia evoked by SMEs is seen in both the places of collective memory and in the motivational forces of individual memory. Thus, SMEs generate collective memory, which eventually leads to sustainable behaviour, re-connecting individuals’ cognitive and emotional states to their past memory [

53,

54]. As such, nostalgia is considered as a core sentiment among the motivational drivers of SMEs. One-off and month-long SMEs (whether they recur annually or every four years) provide memorable moments for individuals in host nations through a variety of tangible and intangible entities, ranging from promotional merchandise to multibillion-dollar facilities [

49]. However, the effects of the dynamics of collective past memories on consumers behaviour have not received adequate attention in the literature on sport spectatorship in the context of SMEs.

2.3. The Conceptualization of Nostalgia in Leisure Activity and Sport

Owing to the intrinsic characteristics of nostalgia, in its engagement with various external stimuli within an individual’s cognitive and affective mental processing, sport tourism disciplines have started to identify the antecedents of nostalgia empirically. They analyse the manner, time, and circumstances in which nostalgia is evoked. The empirical approach conceptualises nostalgia and establishes a foundation for its understanding in the context of sport tourism [

54].

In an attempt to evaluate nostalgia empirically, Cho et al. [

55] developed a leisure nostalgia scale (LNS) by integrating Fairley and Gammon’s [

42] conceptualisation of nostalgia in sport tourism. The LNS was categorised based on the following antecedents, which are most relevant to engendering a nostalgic feeling: experience, environment, socialisation, personal identity, and group identity [

55,

56]. When an LNS was applied to and implemented across the research on sport and leisure, it was found that nostalgia, as a multidimensional psychological construct, has motivational effects on an individual’s behaviour changes [

55,

56]. Based on the principle of stimuli and responses in human behaviour [

57], Cho et al. [

55] concluded that nostalgia evoked by external stimuli, such as experience, environment, socialisation, and personal and group identity, influences an individual’s future behaviour reactions.

Drawing on this finding, the present study develops the following hypotheses by adding nostalgia as a mediating contributor in the relationship between the past World Cup experience and present football spectatorship. Since the LNS is a multidimensional construct composed of five factors, this study identifies the manner in which spectators’ behaviour changes with each factor (e.g., nostalgic evocation), and how each nostalgia factor acts as a mediator between past experience and present sport spectatorship. Therefore, we hypothesise that the effect of nostalgia is a mediator in the relationship between SMEs and sport spectatorship.

Nostalgia as an experience. It was assumed that an individual’s past experience with sports teams and players, and their event experiences as spectators, including cheering for teams, players, or coaches, can cause nostalgia, as evoked by SMEs. Thus, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a). Nostalgia evoked by the overall experience of the 2002 World Cup positively mediates the relationship between the past World Cup experience and present football spectatorship.

Nostalgia as an environment. Nostalgia as a leisure environment accounts for an individual’s psychological attachment to physical and emotional objects, such as places, facilities, equipment, and the atmosphere (i.e., the weather). Thus, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 2b (H2b). Nostalgia evoked by the environment during the 2002 World Cup positively mediates the relationship between the past World Cup experience and present football spectatorship.

Nostalgia as socialisation. The third component of nostalgia is socialisation. In other words, nostalgia can be evoked by relationship-building experiences when people interact with others during SMEs; that is, they make new friends, share information with friends, or cheer for their teams together. Thus, the following hypothesis was suggested:

Hypothesis 2c (H2c). Nostalgia from socialisation during the 2002 World Cup positively mediates the relationship between the past World Cup experience and present football spectatorship.

Nostalgia as a personal identity. This component assumes that the experience of following sport events, players, coaches, or teams generates self-identity for a fan. This eventually evokes nostalgia in association with past memories. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2d (H2d) Nostalgia from personal identity generated during the 2002 World Cup positively mediates the relationship between the past World Cup experience and present football spectatorship.

Nostalgia as group identity. The last component of nostalgia is group identity, wherein people sharing the same norms and values achieve a sense of belonging. This bonding, often called the “band of brothers or sisters effect”, generates collective memory, which, in turn, influences the group’s nostalgic sentiments. However, in the context of international SMEs, the authors conceptualised this element as a national identity by expanding the scope of the meaning of a “group”. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2e (H2e). The sense of nostalgia from national identity generated during the 2002 World Cup positively mediates the relationship between the past World Cup experience and present football spectatorship.

Since the 2002 World Cup was hosted by South Korea and Japan, the present study identified the differences in the changes in spectator behaviour for each country. South Korea and Japan, located in the Far East with a close geographical proximity to each other, share a similar trajectory regarding the introduction of association of football between the mid to late 19th century [

58,

59]. However, the way in which modern football was organised, developed, and diffused was different in each country [

60,

61]. Moreover, the international presence and professionalisation of the sport, key drivers for football spectatorship, have progressed in a somewhat contrasting manner according to the literature. South Korea have focused on international success and elite development [

62,

63,

64], while Japan have focused on mass participation, the development of a professional football league, and football fandom [

65,

66,

67]. We used a cross-cultural approach based on the assumption that different cultural backgrounds are likely to result in different behaviour outcomes in football spectatorship after an SME [

14,

68,

69]. Based on these arguments, the present study attempted to answer an additional research question, alongside the above hypotheses:

Research Question 1 (RQ1). Does the mediating effect of nostalgia differ based on nationality?